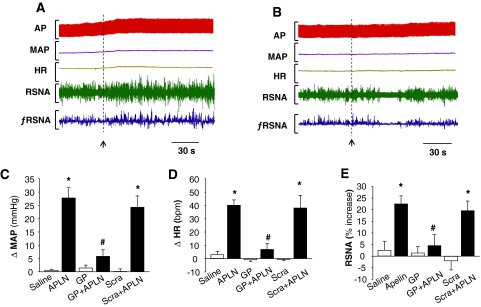

Fig. 1.

Role of NAD(P)H oxidase in the pressor response to apelin-13 microinjected in the RVLM. A and B, representative tracings showing arterial pressure (AP), MAP, HR, RSNA, and integrated RSNA (ƒRSNA) before and after microinjection of apelin-13 (200 pmol, 50 nl) into the RVLM of SD rats pretreated with scrambled gp91ds-tat (Scra, 2.5 nmol, 50 nl, 18 min) (A) or NADPH oxidase inhibitor gp91ds-tat (GP, 2.5 nmol, 50 nl, 18 min) (B). C, bar graphs summarizing the change of MAP (ΔMAP) induced by RVLM microinjection (50 nl) of saline, apelin-13 (APLN, 200 pmol), gp91ds-tat (GP, 2.5 nmol), GP plus apelin-13 (GP+APLN), scrambled gp91ds-tat (Scra, 2.5 nmol), and scrambled gp91ds-tat plus apelin-13 (Scra+APLN). Data are means ± S.E. (n = 5 to 7 rats in each group). *, P < 0.01 significant difference compared with respective control. #, P < 0.05 versus APLN. D, bar graphs summarizing the change of heart rate (ΔHR) induced by RVLM microinjection of agents described in C. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 5 to 7 rats in each group). *, P < 0.01 significant difference compared with respective control. #, P < 0.05 versus APLN. E, bar graphs summarizing the percentage increases of RSNA after RVLM microinjection of agents described in C. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 5 to 7 rats in each group). *, P < 0.01 significant difference compared with respective control. #, P < 0.05 versus apelin-13 (APLN).