Abstract

The genus Conexibacter (Monciardini et al. 2003) represents the type genus of the family Conexibacteraceae (Stackebrandt 2005, emend. Zhi et al. 2009) with Conexibacter woesei as the type species of the genus. C. woesei is a representative of a deep evolutionary line of descent within the class Actinobacteria. Strain ID131577T was originally isolated from temperate forest soil in Gerenzano (Italy). Cells are small, short rods that are motile by peritrichous flagella. They may form aggregates after a longer period of growth and, then as a typical characteristic, an undulate structure is formed by self-aggregation of flagella with entangled bacterial cells. Here we describe the features of the organism, together with the complete sequence and annotation. The 6,359,369 bp long genome of C. woesei contains 5,950 protein-coding and 48 RNA genes and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project.

Keywords: aerobic, short rods, forest soil, Solirubrobacterales, Conexibacteraceae, GEBA

Introduction

Strain ID131577T (= DSM 14684 = JCM 11494) is the type strain of the species Conexibacter woesei, which is the type species of the genus Conexibacter. Strain ID131577T was originally enriched from a soil sample used for isolation of filamentous actinomycetes and was first detected as a contaminant of a Dactylosporangium colony [1]. Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis and the composition of their signature oligonucleotides, the strain was subsequently assigned to the subclass Rubrobacteridae within the class Actinobacteria [2]. Stackebrandt first placed the species C. woesei to the order Rubrobacterales [3,4]. With the description of Patulibacter americanus [5], the new order Solirubrobacterales was defined, again by the presence of 16S rRNA gene sequence signature oligonucleotides. The order Solirubrobacterales presently embraces the three families Solirubrobacteraceae, Patulibacteraceae, and Conexibacteraceae [5]; an emended description of the family Conexibacteraceae was published recently by Zhi et al. 2009 [6]. Several distantly related uncultured bacterial clones with less than 97% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to C. woesei were detected in various environmental habitats such as soil [7,8]; (EU223949, GQ366411), soil crusts [9], Fe-nodules of quaternary sediments in Japan [10], sediment (FN423884), rhizosphere [11], acidic Sphagnum peat bog [12], fleece rot (DQ221822), and salmonid gill [13]. Conexibacter related strains may also act as opportunistic pathogens as described in a few reports in which uncultured bacterial relatives were detected in bronchoalveolar fluid of a child with cystic fibrosis [14], or as enriched participants of showerhead biofilms [15]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for C. woesei ID131577T, together with the description of the complete genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

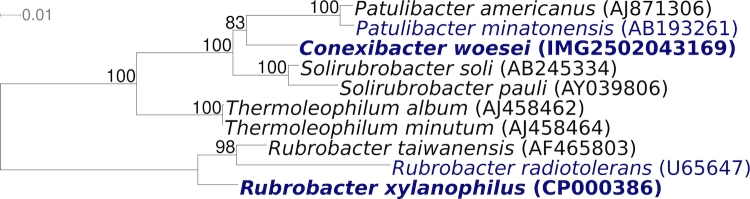

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood for C. woesei ID131577T in a 16S rRNA based tree. The single 16S rRNA gene sequence in the genome of C. woesei ID131577T is 1,536 bp long. The previously published 16S rRNA sequence (AJ440237) covered 1,470 bp only, but is identical to the genome-derived sequence in that stretch.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of C. woesei ID131577T relative to the other genera included in the subclass Rubrobacteridae. The tree was inferred from 1,429 aligned characters [16,17] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood criterion [18] and rooted with the order Rubrobacterales. The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers above branches are support values from 1,000 bootstrap replicates if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [19] are shown in blue, published genomes in bold.

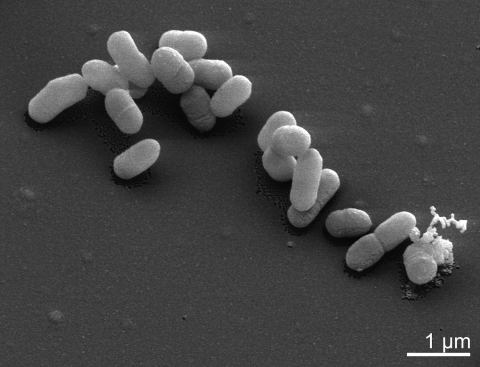

C. woesei is a Gram-positive, aerobic and non-sporulating bacterium, and forms small rods up to 1.2 µm in length (Table 1 and Figure 2). The strain is able to grow on complex media like TSA, BHI, Todd-Hewitt as well as on ISP2, ISP3 or R2A agar [1]. Growth occurs at pH 7-7.5 between 28 and 37°C. Catalase and oxidase activity is present and nitrate is reduced to nitrite. The strain is able to hydrolyze gelatin and esculin, but urea is not decomposed. Preferred substrates for utilization, as tested with the BiOLOG system, are L-arabinose, D-ribose, D-xylose, glycerol, acetic acid, pyruvic acid, propionic acid, α-ketovaleric acid, and ß-hydroxybutyric acid [1]. The strain is susceptible to amikacin, gentamicin, nitrofurantoin, polymyxin B, novobiocin and teichoplanin [1].

Table 1. Classification and general features of C. woesei ID131577T according to the MIGS recommendations [20].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [21] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [22] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [2] | ||

| Subclass Rubrobacteridae | TAS [2] | ||

| Order Solirubrobacterales | TAS [5] | ||

| Family Conexibacteraceae | TAS [3,6] | ||

| Genus Conexibacter | TAS [1] | ||

| Species Conexibacter woesei | TAS [1] | ||

| Type strain ID131577 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | positive | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | short rods | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | long, peritrichous flagella | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | unknown | NAS | |

| Temperature range | 28°C-37°C | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | unknown | ||

| Salinity | < 2% | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | strictly aerobic | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | saccharolytic | TAS [1] | |

| Energy source | carbohydrates | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | soil | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | opportunistic | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | TAS [23] | |

| Isolation | soil | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Gerenzano, Italy | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-4.1 MIGS-4.2 |

Latitude Longitude |

45.640 9.002 |

NAS |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | not reported |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from of the Gene Ontology project [24]. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of C. woesei ID131577T

Chemotaxonomy

C. woesei possesses a peptidoglycan type of A1γ, based on mesoA2pm. Meso-diaminopimelic acid is the diagnostic amino acid at position 3 of the peptidoglycan for all members of the order Solirubrobacterales, whereas members of the Rubrobacterales are characterized by L-Lys as the diamino acid at position 3 (peptidoglycan type A3α, L-Lys ← L-Ala). The tetrahydrogenated menaquinone MK-7(H4) was detected as the major component in C. woesei and Solirubrobacter pauli [1,25]. This is a remarkable feature, because MK-7(H4) if detectable in bacteria, has previously been reported as a minor component only. The main polar lipid was identified by two-dimensional TLC as phosphatidylinositol. Oleic acid (C18:1ω9c), 14-methyl-pentadecanoic acid (i-C16:0), hexadecanoic acid (C16:0) and ω6c-heptadecenoic acid (C17:1ω6c) constituted the major cellular fatty acids [1]. Mycolic acids are absent.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing on the basis of its phylogenetic position, and is part of the Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea project [26]. The genome project is deposited in the Genome OnLine Database [19] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Finished |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two Sanger libraries: 8kb pMCL200 and fosmid pcc1Fos. One 454 pyrosequence standard library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | ABI3730, 454 GS FLX, |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 10.0× Sanger; 19.15× pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 1.1.02.15, phrap |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal, GenePRIMP |

| INSDC ID | CP001854 | |

| Genbank Date of Release | January 15, 2010 | |

| GOLD ID | Gc01185 | |

| NCBI project ID | 20745 | |

| Database: IMG-GEBA | 2501939629 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 14684 |

| Project relevance | Tree of Life, GEBA |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

C. woesei ID131577T, DSM 14684, was grown in DSMZ medium 92 [27] at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5 to 1 g of cell paste using Qiagen Genomic 500 DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with cell lysis modification st/L [26] and over night incubation at 35°C.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Sanger and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at http://www.jgi.doe.gov/. 454 Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler version 1.1.02.15 (Roche). Large Newbler contigs were broken into 6,955 overlapping fragments of 1,000 bp and entered into assembly as pseudo-reads. The sequences were assigned quality scores based on Newbler consensus q-scores with modifications to account for overlap redundancy and to adjust inflated q-scores. A hybrid 454/Sanger assembly was made using the parallel phrap assembler (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with Dupfinisher [28] or transposon bombing of bridging clones (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, custom primer walk or PCR amplification. A total of 1,608 Sanger finishing reads were produced to close gaps, to resolve repetitive regions, and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together all sequence types provided 29.15× coverage of the genome. The final assembly contains 79,136 Sanger and 580,261 pyrosequence reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [29] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [30]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. Additional gene prediction analysis and manual functional annotation was performed within the Integrated Microbial Genomes Expert Review (IMG-ER) platform [31].

Genome properties

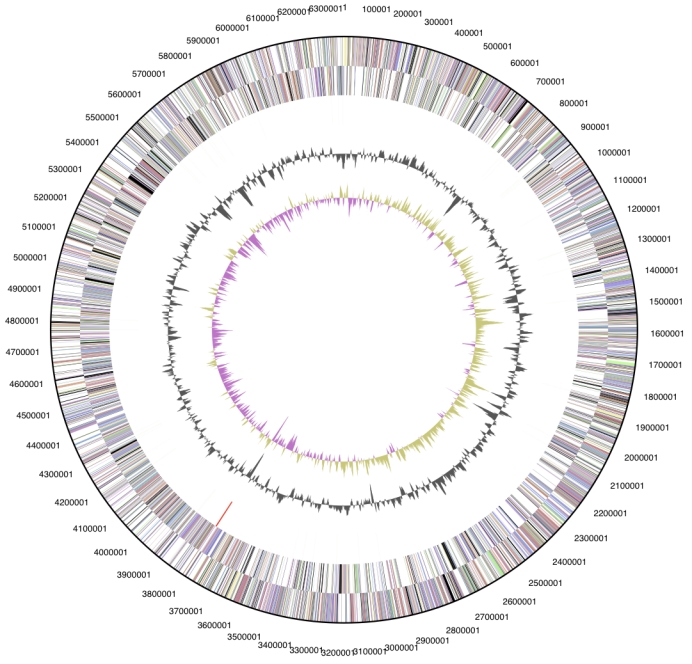

The genome consists of a 6,359,369 bp long chromosome. Of the 5,998 genes predicted, 5,950 were protein-coding genes, and 48 RNAs; 36 pseudogenes were also identified (Table 3 and Figure 3). The majority of the protein-coding genes (74.5%) were assigned with a putative function while those remaining were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 6,359,369 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 6,001,841 | 94.38% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 4,625,387 | 72.73% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 5,998 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 48 | 0.80% |

| rRNA operons | 1 | |

| Protein-coding genes | 5,950 | 99.20% |

| Pseudo genes | 36 | 0.61% |

| Genes with function prediction | 4,466 | 74.46% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 1,697 | 28.52% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 4,419 | 74.27% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 4,500 | 75.03% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,632 | 27.43% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,444 | 24.27% |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0 |

Figure 3.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 197 | 3.9 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 3 | 0.1 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 550 | 10.8 | Transcription |

| L | 120 | 2.3 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.0 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 30 | 0.6 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 89 | 1.7 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 287 | 5.6 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 241 | 4.7 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 57 | 1.1 | Cell motility |

| Z | 1 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 44 | 0.9 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 131 | 2.6 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 325 | 6.4 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 396 | 7.8 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 566 | 11.1 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 84 | 1.6 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 186 | 3.6 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 252 | 4.9 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 301 | 5.9 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 220 | 4.3 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 705 | 13.8 | General function prediction only |

| S | 323 | 6.3 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,579 | 26.3 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis and Katja Steenblock for growing C. woesei cultures and Susanne Schneider for DNA extraction and quality analysis (both at DSMZ). This work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy's Office of Science, Biological and Environmental Research Program, and by the University of California, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344, Los Alamos National Laboratory under contract No. DE-AC02-06NA25396, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725, as well as German Research Foundation (DFG) INST 599/1-1.

References

- 1.Monciardini P, Cavaletti L, Schumann P, Rohde M, Donadio S. Conexibacter woesei gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel representative of a deep evolutionary line of descent within the class Actinobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:569-576 10.1099/ijs.0.02400-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stackebrandt E. Will we ever understand? The undescribable diversity of the prokaryotes. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 2004; 51:449-462 10.1556/AMicr.51.2004.4.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Validation list N° 102. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:547-549 10.1099/ijs.0.63680-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy GS, Garcia-Pichel F. Description of Patulibacter americanus sp. nov., isolated from biological soil crusts, emended description of the genus Patulibacter Takahashi et al. 2006 and proposal of Solirubrobacterales ord. nov. and Thermoleophilales ord. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:87-94 10.1099/ijs.0.64185-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and embedded descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JJ, Tow LA, Stafford W, Cary C, Cowan DA. Bacterial diversity in three different Antarctic Cold Desert mineral soils. Microb Ecol 2006; 51:413-421 10.1007/s00248-006-9022-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann M, Lee S, Hallam SJ, Mohn WW. Bacterial, archaeal and eukaryal community structures throughout soil horizons of harvested and naturally disturbed forest stands. Environ Microbiol 2009; 11:3045-3062 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gundlapally SR, Garcia-Pichel F. The community and phylogenetic diversity of biological soil crusts in the Colorado Plateau studied by molecular fingerprinting and intensive cultivation. Microb Ecol 2006; 52:345-357 10.1007/s00248-006-9011-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida H, Yamamoto K, Murakami Y, Katsuta N, Hayashi T, Naganuma T. The development of Fe-nodules surrounding biological material mediated by microorganisms. Environ Geo 2008; 55:1363-1374 10.1007/s00254-007-1087-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirete S, de Figueras CG, González-Pastor JE. Novel nickel resistance genes from the rhizosphere metagenome of plants adapted to acid mine drainage. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007; 73:6001-6011 10.1128/AEM.00048-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dedysh SN, Pankratov TA, Belova SE, Kulichevskaya IS, Liesack W. Phylogenetic analysis and in situ identification of bacteria community composition in an acidic Sphagnum peat bog. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:2110-2117 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2110-2117.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowman JP, Nowak B. Salmonid gill bacteria and their relationship to amoebic gill disease. J Fish Dis 2004; 27:483-492 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2004.00569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris JK, De Groote MA, Sagel SD, Zemanick ET, Kapsner R, Penvari C, Kaess H, Deterding RR, Accurso FJ, Pace NR. Molecular identification of bacteria in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from children with cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:20529-20533 10.1073/pnas.0709804104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feazel LM, Baumgartner LK, Peterson KL, Frank DN, Harris JK, Pace NR. Opportunistic pathogens enriched in showerhead biofilms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:16393-16399 10.1073/pnas.0908446106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Classification of Bacteria and Archaea in risk groups. www.baua.de TRBA 466.

- 24.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singleton DR, Furlong MA, Peacock AD, White DC, Coleman DC, Whitman WB. Solirubrobacter pauli gen. nov., sp. nov., a mesophilic bacterium within the Rubrobacteridae related to common soil clones. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:485-490 10.1099/ijs.0.02438-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova N, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.List of growth media used at DSMZ: http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/media_list.php

- 28.Sims D, Brettin T, Detter J, Han C, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Chen F, Lucas S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Kytococcus sedentarius type strain (541T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:12-20 10.4056/sigs.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markowitz VM, Mavromatis K, Ivanova NN, Chen IMA, Chu K, Kyrpides NC. Expert IMG ER: A sys-tem for microbial genome annotation, expert re-view and curation. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2271-2278 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]