Abstract

Radiation therapy is a widely used therapeutic approach for cancer. To improve the efficacy of radiotherapy there is an intense interest in combining this modality with two broad classes of compounds, radiosensitizers and radioprotectors. These either enhance tumour-killing efficacy or mitigate damage to surrounding non-malignant tissue, respectively. Radiation exposure often results in the formation of DNA double-strand breaks, which are marked by the induction of H2AX phosphorylation to generate γH2AX. In addition to its essential role in DDR signalling and coordination of double-strand break repair, the ability to visualize and quantitate γH2AX foci using immunofluorescence microscopy techniques enables it to be exploited as an indicator of therapeutic efficacy in a range of cell types and tissues. This review will explore the emerging applicability of γH2AX as a marker for monitoring the effectiveness of radiation-modifying compounds.

Introduction

Radiotherapy is widely used for the management of cancer and relies on ionizing radiation (IR)-induced DNA damage to kill malignant cells. DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are exceptionally lethal lesions can be formed either by direct energy deposition or indirectly through the radiolysis of water molecules, which generate clusters of reactive oxygen species that attack DNA molecules [1-4]. DSBs are essentially two single-stranded nicks in opposing DNA strands that occur in close proximity, severely compromising genomic stability [2,5-7]. Therefore, it is critical that DSBs are repaired quickly and efficiently to prevent cellular death, chromosomal aberrations and mutations [6,8]. A series of complex pathways collectively known as the DNA damage response (DDR) is responsible for the recognition, signalling and repair of DSBs in cells, ultimately resulting in either cell survival or cell death [9,10]. DSBs are repaired by two major pathways, homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), each with distinct and overlapping roles in maintaining genomic integrity. NHEJ, the more error-prone pathway, is commonly employed following IR-induced damage [11]. IR-induced DSBs cause rapid phosphorylation of the histone H2A variant H2AX to form γH2AX. This phosphorylation event takes place at the highly conserved SQ motif, which is a common substrate for the phosphatidyl-inosito 3-kinase (PI3K) family of proteins including ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) [12-16]. Discrete nuclear foci that form as a result of H2AX phosphorylation are now widely used as a sensitive and reliable marker of DSBs [17,18]. Following a discussion of the biology of γH2AX formation, this review will focus on the utility of γH2AX as a molecular marker for monitoring the efficacy of radiation-modifying compounds.

Radiation-induced γH2AX formation

Recent years have witnessed a remarkable proliferation in immunofluorescence-based assays dedicated to the visualization of γH2AX foci. This has emerged as the preferred method of DSB detection given that 20-40 DSBs are estimated to form per Gray of γ-radiation [17,18]. Due to its high sensitivity, DSBs can be distinguished at clinically relevant doses, unlike previous methods which required lysis at high temperatures or large doses of IR (5-50Gy), which are well above biologically relevant doses [19,20]. γH2AX foci detection allows the distinction of the temporal and spatial distribution of DSB formation and can be detected just minutes after γ-radiation, reaching a peak between 30-60 minutes post-irradiation and typically returning to background levels (at relatively lower doses) within 24 hours [2,21]. Comparisons of foci numbers in irradiated or treated samples are made in comparison to appropriate controls and background levels in the cell lines of interest. Interestingly, embryonic stem cells have very high intrinsic levels of γH2AX (more than 100 foci per nucleus) compared to cancer lines (typically 5-20 foci per nucleus) and normal cell lines (typically 1 or 2 foci per nucleus) [22-24]. The characteristics of γH2AX formation have been most widely investigated in the context of γ-radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks, however, γH2AX has also been evaluated following irradiation with high linear energy-transfer (LET) radiations, such as α-particles and heavy ions [25-30]. The γH2AX staining patterns and kinetics observed with high LET radiation differ significantly compared to those from γ-rays, with the major observations being clusters of foci along the ion track that typically exhibit prolonged repair kinetics [30].

Apart from immunofluorescence, Western blotting has also been suggested as another possible method of evaluating the γH2AX response to IR exposure. Data from our laboratory and others have demonstrated that although Western blotting is able to detect the presence of protein in chromatin extracts, it is disadvantaged by the fact that apoptotic cells express extremely high levels of γH2AX, as assessed by immunofluorescence, making it impossible to distinguish between the γH2AX responses of live cells and apoptotic cells [31]. Furthermore, it is very difficult to accurately detect the discrete differences that are typically observed, particularly when the effects of radiation-modifying compounds are being investigated.

Given its unique sensitivity and specificity, immunofluorescence-based detection of foci formation can potentially act as an accurate biodosimeter for exposure to IR following radiation therapy in cancer patients and is a minimally invasive method that requires only the collection of peripheral blood lymphocytes or skin biopsies [32,33]. Assays of γH2AX foci numbers can serve as an indication of the efficacy of various cancer therapies as well as aid in the observation of individual patient radiosensitivities and responses to specific radiation-modifying agents [34-36]. It is important to note, however, that scoring individual γH2AX foci is most accurate at doses below 4Gy (unless DSB repair, for example, 24 hours after irradiation, is being investigated in which cases much higher doses can be examined). When examining initial damage γH2AX foci typically overlap above 4 Gy, as has been shown in our laboratory and others [37]. Methods involving quantitation of total nuclear fluorescence have been employed for monitoring γH2AX formation at higher doses.

γH2AX foci form preferentially in euchromatin

One striking observation about γH2AX is that foci are rarely detected at heterochromatic sites, which typically demonstrate resistance to IR-induced γH2AX foci formation in spite of heterochromatin's rich DNA content [38-41]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis revealed that transcriptionally silent heterochromatic regions are resistant to γH2AX accumulation in both mammalian and yeast cells [38,42]. γH2AX foci distribution within irradiated cells is uneven as foci can only be detected at the periphery of heterochromatic regions rather than within them, the boundaries of which are maintained by methylation of lysine at position 9 on histone H3 (H3K9), an important epigenomic imprint of heterochromatic regions [43,44]. The noticeable lack of H2AX phosphorylation within heterochromatic regions may be attributable to lower vulnerability of compacted DNA to DSB induction, migration of DSBs to the periphery, lower amounts of available H2AX, or possible epigenetic mechanisms that operate in the region to restrict the accessibility of kinases responsible for H2AX phosphorylation [40]. Epigenetic mechanisms appear to be the best possible explanation for the refractory nature of heterochromatin to γH2AX generation as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) have been shown to influence chromatin reorganisation, forcing the movement of DSBs to the periphery of heterochromatic regions [38,45]. Another probability could be that γH2AX foci are epigenetically shielded by loss of heterochromatin features and local chromatin decondensation at DSB sites [46]. With respect to radiomodification, numerous emerging compounds, such as the HDACi discussed below, alter chromatin architecture. Therefore, the use of γH2AX as molecular marker of DSBs in combination with epigenetic markers of euchromatin and heterochromatin would allow correlation of radiomodification and changes in chromatin landscape when investigating relevant compounds.

Radioprotection

One of the major hurdles with respect to radiotherapy use is the preservation of normal tissue while still ensuring the effective killing of tumour cells. Hence, the radiation dose must be limited by the tolerance of non-tumour cells to minimise toxicity to normal, healthy tissue [47]. The issue of therapeutic efficacy has been an important one to address, bringing about the identification and development of compounds such as radiosensitizers and radioprotectors, which either sensitize tumour cells to IR or protect normal cells, respectively [47]. Combining radiotherapy with these radiation-modifying agents is useful in improving therapeutic gain while reducing unintended collateral damage to surrounding normal tissue. Here we discuss, two classes of commonly investigated radioprotectors, the free radical scavengers including amifostine and tempol and the emerging DNA minor groove binding radioprotectors.

Among the first radioprotectors discovered were the sulfhydryl compounds in the early 1950s [48,49]. Amifostine (WR-2721) is a well-characterised radioprotector approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) for the reduction of cisplatin-induced cumulative renal toxicity in ovarian cancer patients and xerostomia in head and neck cancer patients [50,51]. Amifostine is a thiol that confers radioprotection against the toxicity associated with radiation without reducing the efficacy of radiotherapy due to its ability to selectively scavenge radiation-induced radical oxygen species (ROS) before they harm the vulnerable DNA of normal cells [52-54]. Although the extent of radioprotection varies in different tissues, amifostine has broad-spectrum properties that protect non-tumour cells originating from almost all tissue types [50,53-55]. Its selectivity for normal tissue is due to its preferential accumulation in normal tissue compared to the hypoxic environment of tumour tissues with low pH and low alkaline phosphatase, which is required to dephosphorylate and activate amifostine [56,57]. The active metabolite, WR-1065 scavenges free radicals and is oxidised, causing anoxia or the rapid consumption of oxygen in tissues [58]. Amifostine may also cause chromatin compaction, reducing possible sites for ROS activity, thus reducing double strand break (DSB) induction as well as increasing DNA repair and cellular proliferation to aid in the recovery of damaged cells [50]. Maximal radioprotection is observed when amifostine is administered within half an hour before radiation exposure [59,60]. Interestingly, it has been shown that the radioprotective properties of amifostine correlated with a reduction in γH2AX foci in human microvascular endothelial cells [61]. However, this same paper called the use of γH2AX as molecular marker for evaluating the efficacy of radioprotectors into question since the antioxidants N-acetyl-l-cysteine, captopril and mesna protected from radiation-induced γH2AX formation but did not exhibit radioprotective properties by clonogenic survival [61].

Tempol (4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidinyloxy) belongs to a class of water-soluble nitroxides which are membrane-permeable stable free radical compounds that confer protection against radiation-induced damage [62-64]. It is thought to elicit its effects through the oxidation of reduced transition metals, scavenging free radicals and mimicking superoxide dismutase activity [63,65]. In vitro studies have shown that tempol has dose-dependent radioprotective properties which are more efficacious in aerobic conditions as compared to hypoxic environments [66]. Tempol is capable of protecting cells from the mutagenic effects of oxy radicals, aminoxyls and nitroxyls, decreases X-ray induced DSB frequency, and reduces the number of chromosomal aberrations in human peripheral blood cells [67-69]. These findings were also observed in vivo and tempol was shown to be specific for non-tumour cells, which may be attributable to the lack of oxygen or high levels of bioreduction occurring in tumour cells [70]. However, these effects are observed only if tempol is administered immediately before radiation exposure [71]. Interestingly, γH2AX has been employed as a molecular marker to evaluate the effects of tempol in the context of radiation-induced bystander effect [72]. Tempol was found to reduce γH2AX formation in normal human fibroblasts that were exposed to media from UVC-irradiated cells [72].

The DNA minor groove binding bibenzimidazoles represent a different class of potential radioprotectors. Essentially, this group of experimental compounds can be considered as DNA antioxidants that display much greater potency than amifostine and tempol in cell culture systems [73]. DNA minor groove binding radioprotectors are exemplified by the commercially available and widely used DNA stain, Hoechst 33342. Hoechst 33342 binds tightly in the minor groove of DNA predominantly in regions containing four consecutive AATT base pairs [74,75]. The compound is utilised extensively in flow cytometric studies due to its intrinsic fluorescence properties which become amplified once the ligand is bound to DNA. In the early 1980s Hoechst 33342 was shown to possess radioprotective properties which have been subsequently investigated in cell culture systems and in vivo [73,76-82]. Synthetic chemistry was employed to improve the radioprotective properties of Hoechst 33342 leading to the development of the potent analogues, proamine and methylproamine [73,77,78]. Cell culture studies using conventional clonogenic survival assays indicate that methylproamine is the most potent of the three analogues [73]. Recently, γH2AX has been used to further evaluate the radioprotective properties of this compound [83,84]. Studies have indicated that methylproamine protects cells from initial DNA damage following ionizing radiation [83,84]. In accordance, it was identified, using γH2AX as a molecular marker of DSBs, that cells must be pretreated with the compound for radioprotection [83,84]. In summary, γH2AX has emerged as particularly useful marker for evaluating the effects of compounds that protect cells from the effects of ionizing radiation and can provide further insights into radioprotective mechanisms.

Radiation sensitizers

Radiosensitizers enhance the sensitivity of cells to radiation. For example, numerous conventional chemotherapeutics, such as bleomycin, etoposide and the anthracyclines are known to sensitize cells to the effects of ionizing radiation. Doxorubicin is a frontline anti-cancer chemotherapeutic anthracycline which elicits its cytotoxicity through the inhibition of DNA synthesis and DNA topoisomerase II enzymes, chromatin modulation and generation of highly reactive free radicals [85-88]. Tumour resistance and toxicity to normal tissues, especially cardiotoxicity, are major issues in relation to the use of this compound [85]. When combined with radiation, doxorubicin enhances radiosensitivity, especially when administered 4 hours before irradiation [89]. Further evidence of this synergistic effect is highlighted in a clinical study where the combination of radiation and doxorubicin increased response rates and longer remission periods in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, thus increasing patient survival rates [90]. With respect to induction of DSBs and γH2AX, the cytotoxicity of doxorubicin has been widely investigated using this molecular marker. Indeed, one particular study indicated that γH2AX may be used as surrogate marker for clonogenic death induced by doxorubicin and other DSB-inducing genotoxic agents [91]. A recent study has employed γH2AX foci formation to evaluate the DSB-inducing effects of doxorubicin in normal cell cardiomyocytes when used alone and in combination with the HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin A [92]. With respect to combinations of doxorubicin and radiotherapy, an interesting recent finding suggests that low doses of ionizing radiation may suppress doxorubicin-induced senescence as indicated by inhibiting phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase and p53 [93]. The findings indicated that γH2AX levels remained unchanged prompting the authors to conclude that suppression of doxorubicin-induced senescence was not associated with genotoxic damage [93]. In this study, cells were exposed to doxorubicin four hours after low dose (up to 0.2 Gy) ionizing radiation [93]. Overall, these findings highlight the utility of γH2AX as molecular marker for delineating the combinatorial effects of genotoxic agents and ionizing radiation.

Apart from the classical chemotherapeutics, emerging more selective anti-cancer therapeutics are displaying synergistic, or at least additive effects with ionizing radiation. For example, inhibitors of the DNA damage repair enzyme, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) have been shown to suppress resistance to chemotherapy and to enhance the cytotoxic effects of ionizing radiation [94,95]. PARP inhibitors are particularly effective in targeting cancer cells with mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumour suppressor genes [96,97]. Therefore, a number of PARP-inhibiting analogues are currently undergoing clinical trials for BRCA1 and BRCA2 negative advanced breast and ovarian cancers as well as BRCA2 negative prostate cancer [98,99]. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are both implicated in maintaining genomic integrity, at least in part, by their involvement in DNA repair providing a rationale for the effectiveness of PARP inhibitors in malignancies with mutations in these genes [100,101]. Given that PARP inhibitors alter DNA repair, γH2AX has been used as a biomarker for evaluation of the efficacy of these compounds, particularly in combination with other therapeutics, in cancer cell lines [102,103]. Further, γH2AX foci formation has been used to evaluate the combined effects of PARP inhibitors and radiation [94,104]. An exciting new direction is the potential of utilizing poly(ADP-ribosylation) and γH2AX as biomarkers to monitor the effects of PARP inhibitors and combination therapies in clinical samples. This prospect is analysed thoroughly in a recent review [105].

Another, emerging class of potential radiation-modifying compounds that will be discussed is the HDACi. The use of HDAC inhibitors combined with radiation dates back to the 1980s when sodium butyrate was found to potentiate radiosensitivity in cultured cells in vitro [106-108]. Several HDAC inhibitors have since proceeded to clinical trials and the USFDA recently approved the use of suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA or Vorinostat) for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) [109,110]. The molecular mechanisms of action of HDAC inhibitors in enhancing radiation-induced cytotoxicity is thought to involve the transcriptional regulation of genes and impairment of DNA repair processes through the accumulation of acetyl groups on histone and non-histone substrates [109,111-117]. The repression of DDR proteins including ATM, DNA protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), Rad52, Rad51, p53-binding protein 1 (53BP1) and the tumour suppressor breast cancer 1 (BRCA1) is thought to contribute to cell-killing capacity of HDAC inhibitors [117-121]. Additionally, chromatin remodelling due to HDAC inhibitor-mediated hyperacetylation may inhibit the function of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in the late stages of DNA repair when chromatin is restored to its original state [122]. Another effect of HDAC inhibitor-mediated chromatin remodelling is the generation of a less compacted, relatively open chromatin structure which is more vulnerable to radiation damage [123].

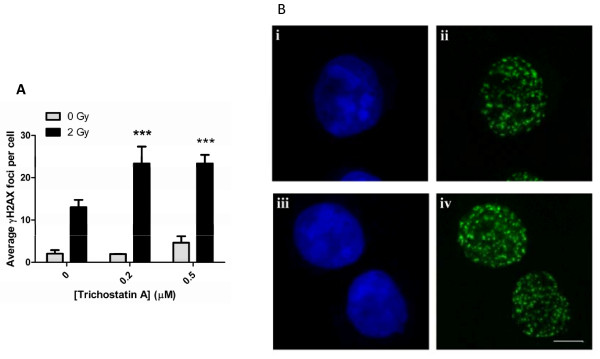

Numerous studies involving radiosensitizers such as HDAC inhibitors have used γH2AX as a marker of radiosensitization [121,124-126]. One study investigating the radiosensitizing effects of Trichostatin A (TSA) found that erythroleukemic cell survival was reduced by over 60% when TSA was administered 24 hours prior to γ-radiation exposure, indicating its efficacy in sensitizing cells to radiation. This coincided with a significant increase in preferential euchromatic formation of γH2AX [38,123]. Other studies support this finding, reporting similar observations in glioblastoma cell lines and non-small cell lung cancer cell lines, with a dose-dependent reduction in cell survival and enhanced γH2AX expression [127,128]. Similar findings were observed with other HDAC inhibitors including SAHA, valproic acid and butyric acid [121,126,129-132]. Notably, tumour cells are more susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of HDAC inhibitors compared to normal cells, an important feature of an efficient radiosensitizer [133]. The radiation sensitizing properties of TSA as assessed by γH2AX immunofluorescence are highlighted in Figure 1. These findings are an extension of our previously published chromatin immunoprecipitation studies which highlight the radiation-sensitizing effects the histone deacetylase inhibitor in K562 cells [134].

Figure 1.

Trichostatin A enhances radiation-induced γH2AX foci formation in K562 cells. Cells were pre-treated with the indicated concentrations of Trichostatin A for 24 hours prior to irradiation (2 Gy, 137Cs). Cells were fixed and stained for γH2AX analysis 1 hour after irradiation. Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 510 meta confocal microscope using 0.5 μm z‐sectioning (63x oil immersion objective). The number of γH2AX foci per nucleus was quantitated using ImageJ (Fiji). Mean ± standard deviations are indicated, *** p < 0.001 (A). Images were exported as TIFF files using Metamorph software for immunofluorescence visualization of nuclei (TO-PRO-3, blue) and γH2AX foci (green). For comparison cells treated with 2 Gy alone (i and ii) and cells exposed to 0.5 μM Trichostatin A prior to 2 Gy irradiation (iii and iv) are shown (B).

Paradoxically, HDAC inhibitors have also been shown to possess radioprotective properties. Treatment of cells in vitro with phenylbutyrate showed higher clonogenic survival of normal cells which correlated with lower γH2AX foci numbers after radiation exposure, indicating that HDAC inhibitors may reduce radiation damage in normal cells [125]. Phenylbutyrate conferred protection of non-tumour cells against chemically induced oral carcinogenesis and oral mucositis, both severe unwanted side effects of radiation [125].

A well-known issue in radiation oncology is the relative radioresistance of hypoxic cells that exist within solid tumors compared to normoxic malignant cells. Attempts to circumvent the problem associated with tissue hypoxia in radiotherapy include the evaluation of radiation sensitizers, particularly nitroimidazoles, a practise which dates back several decades [135,136]. Numeorus compounds have been identified and evaluated as potential radiosensitisers of hypoxic cells including convetional anticancer chemotherapeutics, bioreductive agents and inhibitors of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) as reviewed recently [137]. Evaluation of DNA damage using γH2AX as a molecular marker has been employed both in cell culture and in vivo studies, to investigate the efficacy of compounds including PX-478 (an HIF-1α inhibitor), nitric oxide (thought to react with free radicals on the DNA), etoposide (classical topoisomerase II inhibitor) and tirapazamine (an hypoxic cell targeting bioreductive cytotoxin) [138-142]. Apart from being a useful marker for the evaluation of the efficacy of radiosensitizers of hypoxic cells, it is noteworthy that a seminal study has identified the critical role of γH2AX and therefore, by extrapolation of the DNA damage response, in hypoxia-induced neovascularization in endothelial cells [143].

In vivo γH2AX models

Overall the in vitro studies with radiation protective and radiosensitizing compounds to date highlight the utility of quantitating γH2AX foci as means of examining the efficacy of radiation-modulating compounds in vitro as it produces results that, more often than not reflect, data from clonogenic cell survival assays. However, in vivo studies to determine the efficacies of radiation-modifying compounds are critical before advancing to preclinical and clinical trials. Radiation therapy results in various tissue-specific effects which can be monitored in vivo through a variety of radiobiological models. Among the most well-characterised models are erythema, edema and moist desquamation when the epidermis is exposed to sub-lethal doses of radiation [144,145]. Maximal levels of moist desquamation occur at 20 days post-irradiation, while erythema and edema peak a day or two following radiation exposure [145]. Radiation injury can also be detected using murine colonic mucosal studies as the radiosensitivity of colonic mucosal cells reflects the radiosensitivity of other cells of epithelial origin [146]. Given that the colonic mucosa possesses regeneration capacity, its recovery from radiation injury is a good indicator of the effects of radiation in vivo [146]. Another well-established mouse tongue model has been used for studying radiobiological studies on oral mucositis since the early 1990s [147,148]. Oral mucositis is an adverse complication associated with radiotherapy of head and neck cancers. The mouse tongue model allows the evaluation of prophylactic and therapeutic approaches to treatment of oral mucositis [59]. In this model, radiation-induced changes of the mouse tongue epithelium are scored on a daily basis from the onset of first symptoms such as erosions and ulcerations until complete repopulation of the epithelium [148,149].

The models outlined above are well-established and suitable for the monitoring of tissue responses over specified durations however, a major limitation is the need to monitor tissue responses over protracted time periods. Evaluation of γH2AX in vivo is emerging as a promising alternative with many studies demonstrating its exquisite sensitivity and reliability [150-152]. Several studies have deduced that γH2AX is a useful indicator for investigating the response of normal and tumour tissues to irradiation as well as for the prediction of individual responses to radiation therapy [150-152]. The immunofluorescence assay has been applied to evaluate DNA damage following irradiation in a range of cell types and tissues, including peripheral blood lymphocytes, skin biopsies and thymic tissues [153-155]. In an interesting recent study, a radiation dose-dependent increase in γH2AX foci was observed in exfoliated buccal mucosal cells following radiation [150]. Given the significance of buccal mucosal cell injury in radiation-induced xerostomia, this model may be suitable for adaptation for the evaluation of potential radiation modifying compounds. Similarly, a recent model indicates the predictive nature of quantitating γH2AX in murine skin following radiation [151]. It was identified that residual foci, 10 days after irradiation, may be the most accurate for determining radiosensitivity [151]. Again, given the clinical problems associated with radiation-induced skin injury, adaptation of this model may provide a means for evaluating the effects of radiomodifiers. However, largely to difficulties in establishing dose-responses that accurately depict radiosensitivity in different cell types and with issues with quantitating γH2AX foci in various cell types in tissue sections (typically 5-8 μm sections and up to 20 μm), widespread use of in vivo models for evaluating the effects of radiation-modifying compounds is still limited.

High through-put screening

The γH2AX immunofluorescence-based assay is currently the most sensitive and robust method for detecting DSBs, prompting research into the development of automated methods to expedite processing and analysis of γH2AX foci [156]. This field is progressing steadily, with developments including automated specimen preparation and computerised image acquisition, digital analysis and computer-based algorithms [153,157,158]. Recently, an automated 96-well immunohistochemistry and microscopy system was unveiled, which can increase the efficiency of γH2AX analysis with reproducible results that correspond to those obtained manually, and could potentially be adapted for high-throughput applications [159].

Large-scale radiological events and the development of new radiopharmaceuticals that modulate radiation sensitivity call for high throughput biodosimetry, utilising γH2AX as a biomarker of DNA damage. Several groups have addressed the need for high throughput evaluation of γH2AX, and one notable advance in this field is the design of an automated system known as RABIT (Rapid Automated Biodosimetry Tool), based on the well-established γH2AX immunofluorescence assay [160]. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells are easily obtained with minimal invasion, have very low levels of background γH2AX expression and low inter-individual variations, validating its use as a tissue sample for damage detection following radiation exposure [19,161,162]. Optimisations are still under way with the development of the RABIT system and its completion will provide a significant boost for the assessment of radiation exposure in humans as well as for monitoring the efficacy of existing and potential radiation-modifying compounds.

Conclusions

In summary, γH2AX is a widely used molecular marker for monitoring the efficacy of radiation-modifying compounds in vitro. However, the assay has not yet surpassed the traditional radiobiological models for preclinical studies with radiation-modifying compounds. On the basis of its popularity in the detection of radiation-induced DNA damage in cell culture studies, and given its reproducibility and reliability, the immunofluorescence assay is likely to become more widely employed in vivo. It is expected that with advances in 3D imaging and analysis, superior predictive models of tissue damage based on γH2AX will be established. Finally, it would be a major accomplishment if the assay can be adapted for high-throughput evaluation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TCK and AE provided the outline and drafted the manuscript. KV and RSV drafted the radiation-induced and γH2AX formation and γH2AX foci form preferentially in euchromatin sections, respectively and provided the figures for the manuscript. LM and CO drafted the radioprotector and radiation sensitizer sections, respectively. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Li-Jeen Mah, Email: li-jeen.mah@bakeridi.edu.au.

Christian Orlowski, Email: christian.orlowski@bakeridi.edu.au.

Katherine Ververis, Email: katherine.ververis@bakeridi.edu.au.

Raja S Vasireddy, Email: raja.vasireddy@qut.edu.au.

Assam El-Osta, Email: assam.el-osta@bakeridi.edu.au.

Tom C Karagiannis, Email: tom.karagiannis@bakeridi.edu.au.

Acknowledgements

The support of the Australian Institute of Nuclear Science and Engineering is acknowledged. TCK was the recipient of AINSE awards. Epigenomic Medicine Laboratory is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (566559). This work is funded by the CRC for Biomedical Imaging Development Ltd (CRC-BID), established and supported under the Australian Government's Cooperative Research Centres program. CO and LM are the recipients of Australian post-graduate award and Melbourne Research scholarship, respectively, and CRC-BID supplementary scholarships.

References

- Little JB. Genomic instability and radiation. J Radiol Prot. 2003;23:173–181. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/23/2/304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelnikova OA, Pilch DR, Redon C, Bonner WM. Histone H2AX in DNA damage and repair. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2003;2:233–235. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet J, Delatour T, Douki T, Gasparutto D, Pouget J, Ravanat J, Sauvaigo S. Hydroxyl radicals and DNA base damage. Mutat Res. 1999;424:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget JP, Mather SJ. General aspects of the cellular response to low- and high-LET radiation. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:541–561. doi: 10.1007/s002590100484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis TC, El-Osta A. Double-strand breaks: signaling pathways and repair mechanisms. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2137–2147. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4174-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna KK, Jackson SP. DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat Genet. 2001;27:247. doi: 10.1038/85798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastink A, Lohman PHM. Repair and consequences of double-strand breaks in DNA. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 1999;428:141–156. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5742(99)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich T, Allen RL, Wyllie AH. Defying death after DNA damage. Nature. 2000;407:777–783. doi: 10.1038/35037717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki M, Clapperton JA, Mohammad D, Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ, Jackson SP. MDC1 Directly Binds Phosphorylated Histone H2AX to Regulate Cellular Responses to DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Cell. 2005;123:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda E, Hochegger H, Saberi A, Taniguchi Y, Takeda S. Differential usage of non-homologous end-joining and homologous recombination in double strand break repair. DNA Repair. 2006;5:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastav M, De Haro LP, Nickoloff JA. Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Res. 2008;18:134–147. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Capetillo O, Chen HT, Celeste A, Ward I, Romanienko PJ, Morales JC, Naka K, Xia Z, Camerini-Otero RD, Motoyama N. et al. DNA damage-induced G2-M checkpoint activation by histone H2AX and 53BP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:993. doi: 10.1038/ncb884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees-Miller SP, Sakaguchi K, Ullrich SJ, Appella E, Anderson CW. Human DNA-activated protein kinase phosphorylates serines 15 and 37 in the amino-terminal transactivation domain of human p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5041–5049. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson K, Stenerlöw B. Focus formation of DNA repair proteins in normal and repair-deficient cells irradiated with high-LET ions. Radiat Res. 2004;161:517–527. doi: 10.1667/RR3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherbarrow EL, Harper JV, Cucinotta FA, O'Neill P. Induction and quantification of g-H2AX foci following low and high LET-irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2006;82:111–118. doi: 10.1080/09553000600599783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner WM. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelnikova OA, Rogakou EP, Panyutin IG, Bonner WM. Quantitative detection of (125) IdU-induced DNA double-strand breaks with gamma-H2AX antibody. Radiat Res. 2002;158:486–492. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)158[0486:QDOIID]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothkamm K, Lobrich M. Evidence for a lack of DNA double-strand break repair in human cells exposed to very low x-ray doses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5057–5062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830918100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HT, Bhandoola A, Difilippantonio MJ, Zhu J, Brown MJ, Tai X, Rogakou EP, Brotz TM, Bonner WM, Ried T, Nussenzweig A. Response to RAG-Mediated V(D)J Cleavage by NBS1 and {gamma}-H2AX. Science. 2000;290:1962–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5498.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markova E, Schultz N, Belyaev IY. Kinetics and dose-response of residual 53BP1/gamma-H2AX foci: Co-localization, relationship with DSB repair and clonogenic survival. Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83:319–329. doi: 10.1080/09553000601170469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura AJ, Redon CE, Sedelnikova OA. Where did they come from? The origin of endogenous gamma-H2AX foci in tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2324. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, MacPhail SH, Banath JP, Klokov D, Olive PL. Endogenous expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX in tumors in relation to DNA double-strand breaks and genomic instability. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:935–946. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banath JP, Banuelos CA, Klokov D, MacPhail SM, Lansdorp PM, Olive PL. Explanation for excessive DNA single-strand breaks and endogenous repair foci in pluripotent mouse embryonic stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1505–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JA, Harper JV, Cucinotta FA, O'Neill P. Participation of DNA-PKcs in DSB repair after exposure to high- and low-LET radiation. Radiat Res. 2010;174:195–205. doi: 10.1667/RR2071.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid TE, Dollinger G, Beisker W, Hable V, Greubel C, Auer S, Mittag A, Tarnok A, Friedl AA, Molls M, Roper B. Differences in the kinetics of gamma-H2AX fluorescence decay after exposure to low and high LET radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:682–691. doi: 10.3109/09553001003734543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig AI, Hight SK, Minna JD, Shay JW, Rusek A, Story MD. DNA damage intensity in fibroblasts in a 3-dimensional collagen matrix correlates with the Bragg curve energy distribution of a high LET particle. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:194–204. doi: 10.3109/09553000903418603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Yamakawa N, Kirita T, Omori K, Ishioka N, Furusawa Y, Mori E, Ohnishi K, Ohnishi T. DNA damage recognition proteins localize along heavy ion induced tracks in the cell nucleus. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2008;49:645–652. doi: 10.1269/jrr.08007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherbarrow EL, Harper JV, Cucinotta FA, O'Neill P. Induction and quantification of gamma-H2AX foci following low and high LET-irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2006;82:111–118. doi: 10.1080/09553000600599783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai N, Davis E, O'Neill P, Durante M, Cucinotta FA, Wu H. Immunofluorescence detection of clustered gamma-H2AX foci induced by HZE-particle radiation. Radiat Res. 2005;164:518–522. doi: 10.1667/RR3431.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerhahn S, Egly JM. Tools to study DNA repair: what's in the box? Trends Genet. 2008;24:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redon CE, Dickey JS, Bonner WM, Sedelnikova OA. [gamma]-H2AX as a biomarker of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation in human peripheral blood lymphocytes and artificial skin. Advances in Space Research. 2009;43:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.asr.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelnikova OA, Bonner WM. gamma H2AX in cancer cells: A potential biomarker for cancer diagnostics, prediction and recurrence. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2909–2913. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.24.3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, Guldberg P, Sehested M, Nesland JM, Lukas C. et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorgoulis VG, Vassiliou L-VF, Karakaidos P, Zacharatos P, Kotsinas A, Liloglou T, Venere M, DiTullio RA, Kastrinakis NG, Levy B. et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature. 2005;434:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nature03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive PL, Banath JP. Phosphorylation of histone H2AX as a measure of radiosensitivity. 2004. pp. 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rothkamm K, Kruger I, Thompson LH, Lobrich M. Pathways of DNA Double-Strand Break Repair during the Mammalian Cell Cycle. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5706–5715. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5706-5715.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis TC, Harikrishnan KN, El-Osta A. Disparity of histone deacetylase inhibition on repair of radiation-induced DNA damage on euchromatin and constitutive heterochromatin compartments. Oncogene. 2007;26:3963–3971. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi AA, Noon AT, Deckbar D, Ziv Y, Shiloh Y, Löbrich M, Jeggo PA. ATM Signaling Facilitates Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks Associated with Heterochromatin. Mol Cell. 2008;31:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell IG. gammaH2AX foci form preferentially in euchromatin after ionising-radiation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasireddy RS, Karagiannis TC, El-Osta A. gamma-radiation-induced gammaH2AX formation occurs preferentially in actively transcribing euchromatic loci. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:291–294. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Kruhlak M, Dotiwala F, Nussenzweig A, Haber JE. Heterochromatin is refractory to gammaH2AX modification in yeast and mammals. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:209–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonner WM, Redon CE, Dickey JS, Nakamura AJ, Sedelnikova OA, Solier S, Pommier Y. Gamma H2AX and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8:957–967. doi: 10.1038/nrc2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin Modifications and Their Function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A, Maison C, Roche D, Almouzni G. Reversible disruption of pericentric heterochromatin and centromere function by inhibiting deacetylases. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:114–120. doi: 10.1038/35055010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruhlak MJ, Celeste A, Dellaire G, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Muller WG, McNally JG, Bazett-Jones DP, Nussenzweig A. Changes in chromatin structure and mobility in living cells at sites of DNA double-strand breaks. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:823–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne-Daly C. Principles of radiotherapy and radiobiology. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1999;15:250–259. doi: 10.1016/S0749-2081(99)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacq Z, Dechamps G, Fischer P, Herve A, Le Bihan H, Lecomte J, Pirotte M, Rayet P. Protection against x-rays and therapy of radiation sickness with beta-mercaptoethylamine. Science. 1953;117:633–636. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3049.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patt H, Tyree E, Straube R, Smith D. Cysteine Protection against X Irradiation. Science. 1949;110:213–214. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2852.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouvaris JR, Kouloulias VE, Vlahos LJ. Amifostine: The First Selective-Target and Broad-Spectrum Radioprotector. Oncologist. 2007;12:738–747. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-6-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcu LG. The role of amifostine in the treatment of head and neck cancer with cisplatin-radiotherapy. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2009;18:116–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley ML, Schuchter LM, Lindley C, Meropol NJ, Cohen GI, Broder G, Gradishar WJ, Green DM, Langdon RJ Jr, Mitchell RB. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Use of Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy Protectants. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3333–3355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukourakis M. Amifostine: is there evidence of tumor protection? Semin Oncol. 2003;30:18–30. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse A, Clark L, Sasse E, Clark O. Amifostine reduces side effects and improves complete response rate during radiotherapy: results of a meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhas J, Spellman J, Culo F. The role of WR-2721 in radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. Cancer Clin Trials. 1980;3:211–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabro-Jones P, Fahey R, Smoluk G, Ward J. Alkaline phosphatase promotes radioprotection and accumulation of WR-1065 in V79-171 cells incubated in medium containing WR-2721. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1985;47:23–27. doi: 10.1080/09553008514550041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuhas JM. Active versus Passive Absorption Kinetics as the Basis for Selective Protection of Normal Tissues by S-2-(3-Aminopropylamino)-ethylphosphorothioic Acid. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1519–1524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie J, Inhaber E, Schneider H, Labelle J. Interaction of cultured mammalian cells with WR-2721 and its thiol, WR-1065: implications for mechanisms of radioprotection. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1983;43:517–527. doi: 10.1080/09553008314550611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonadou D, Pepelassi M, Synodinou M, Puglisi M, Throuvalas N. Prophylactic use of amifostine to prevent radiochemotherapy-induced mucositis and xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:739–747. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)02683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizel DM, Wasserman TH, Henke M, Strnad V, Rudat V, Monnier A, Eschwege F, Zhang J, Russell L, Oster W, Sauer R. Phase III Randomized Trial of Amifostine as a Radioprotector in Head and Neck Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3339–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.19.3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka Y, Murley JS, Baker KL, Grdina DJ. Relationship between phosphorylated histone H2AX formation and cell survival in human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC) as a function of ionizing radiation exposure in the presence or absence of thiol-containing drugs. Radiat Res. 2007;168:106–114. doi: 10.1667/RR0975.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett H, Swartz H, Brown Rr, Koenig S. Modification of relaxation of lipid protons by molecular oxygen and nitroxides. Invest Radiol. 1987;22:502–507. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198706000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn SM, Krishna CM, Samuni A, DeGraff W, Cuscela DO, Johnstone P, Mitchell JB. Potential Use of Nitroxides in Radiation Oncology. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2006s–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscoli C, Cuzzocrea S, Riley D, Zweier J, Thiemermann C, Wang Z, Salvemini D. On the selectivity of superoxide dismutase mimetics and its importance in pharmacological studies. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:445–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune D, Hasanuzzaman M, Pitcock A, Francis J, Sehgal I. The superoxide scavenger TEMPOL induces urokinase receptor (uPAR) expression in human prostate cancer cells. Molecular Cancer. 2006;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J, DeGraff W, Kaufman D, Krishna M, Samuni A, Finkelstein E, Ahn M, Hahn S, Gamson J, Russo A. Inhibition of oxygen-dependent radiation-induced damage by the nitroxide superoxide dismutase mimic, tempol. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;289:62–70. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90442-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGraff W, Krishna M, Kaufman D, Mitchell J. Nitroxide-mediated protection against X-ray- and neocarzinostatin-induced DNA damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13:479–487. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGraff W, Krishna M, Russo A, Mitchell J. Antimutagenicity of a low molecular weight superoxide dismutase mimic against oxidative mutagens. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1992;19:21–26. doi: 10.1002/em.2850190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusto O, Trindade DF, Linares E, Vaz SM. Cyclic nitroxides inhibit the toxicity of nitric oxide-derived oxidants: mechanisms and implications. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2008;80:179–189. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652008000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy K, Teicher B, Rockwell S, Sartorelli A. The hypoxic tumor cell: a target for selective cancer chemotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90235-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn SM, Tochner Z, Krishna CM, Glass J, Wilson L, Samuni A, Sprague M, Venzon D, Glatstein E, Mitchell JB, Russo A. Tempol, a Stable Free Radical, Is a Novel Murine Radiation Protector. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1750–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey JS, Baird BJ, Redon CE, Sokolov MV, Sedelnikova OA, Bonner WM. Intercellular communication of cellular stress monitored by gamma-H2AX induction. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1686–1695. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RF, Broadhurst S, Reum ME, Squire CJ, Clark GR, Lobachevsky PN, White JM, Clark C, Sy D, Spotheim-Maurizot M, Kelly DP. In vitro studies with methylproamine: a potent new radioprotector. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1067–1070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pjura PE, Grzeskowiak K, Dickerson RE. Binding of Hoechst 33258 to the minor groove of B-DNA. J Mol Biol. 1987;197:257–271. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram M, van der Marel GA, Roelen HL, van Boom JH, Wang AH. Conformation of B-DNA containing O6-ethyl-G-C base pairs stabilized by minor groove binding drugs: molecular structure of d(CGC[e6G]AATTCGCG complexed with Hoechst 33258 or Hoechst 33342. EMBO J. 1992;11:225–232. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubimova NV, Coultas PG, Yuen K, Martin RF. In vivo radioprotection of mouse brain endothelial cells by Hoechst 33342. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:77–82. doi: 10.1259/bjr.74.877.740077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RF, Anderson RF. Pulse radiolysis studies indicate that electron transfer is involved in radioprotection by Hoechst 33342 and methylproamine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:827–831. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RF, Broadhurst S, D'Abrew S, Budd R, Sephton R, Reum M, Kelly DP. Radioprotection by DNA ligands. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1996;27:S99–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison L, Haigh A, D'Cunha G, Martin RF. DNA ligands as radioprotectors: molecular studies with Hoechst 33342 and Hoechst 33258. Int J Radiat Biol. 1992;61:561. doi: 10.1080/09553009214550641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RF, Denison L. DNA ligands as radiomodifiers: studies with minor-groove binding bibenzimidazoles. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:579–584. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison L, Haigh A, D'Cunha G, Martin RF. DNA ligands as radioprotectors: molecular studies with Hoechst 33342 and Hoechst 33258. Int J Radiat Biol. 1992;61:69–81. doi: 10.1080/09553009214550641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SD, Hill RP. Radiation sensitivity of tumour cells stained in vitro or in vivo with the bisbenzimide fluorochrome Hoechst 33342. Br J Cancer. 1989;60:715–721. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobachevsky PN, Vasireddy RS, Broadhurst S, Sprung CN, Karagiannis TC, Smith AJ, Radford IR, McKay MJ, Martin RF. Protection by methylproamine of irradiated human keratinocytes correlates with reduction of DNA damage. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sprung CN, Vasireddy RS, Karagiannis TC, Loveridge SJ, Martin RF, McKay MJ. Methylproamine protects against ionizing radiation by preventing DNA double-strand breaks. Mutat Res. 2010;692:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortobágyi G. Anthracyclines in the treatment of cancer. An overview. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 4):1–7. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199700544-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz D. A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:727–741. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman J. Single-hit mechanism of tumour cell killing by radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:71–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss R. The anthracyclines: will we ever find a better doxorubicin? Semin Oncol. 1992;19:670–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Williams JR. Time-targeted therapy (TTT): Proof of principle using doxorubicin and radiation in a cultured cell system. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:621–627. doi: 10.1080/02841860601009448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolarić K. Combination of cytostatics and radiation--a new trend in the treatment of inoperable esophageal cancer. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;201:259–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banath JP, Olive PL. Expression of phosphorylated histone H2AX as a surrogate of cell killing by drugs that create DNA double-strand breaks. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4347–4350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis TC, Lin AJ, Ververis K, Chang L, Tang MM, Okabe J, El-Osta A. Trichostatin A accentuates doxorubicin-induced hypertrophy in cardiac myocytes. Aging (Albany NY) 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shin JS, Woo SH, Lee HC, Hong SW, Yoo DH, Hong SI, Lee WJ, Lee MS, Jin YW, An S. et al. Low doses of ionizing radiation suppress doxorubicin-induced senescence-like phenotypes by activation of ERK1/2 and suppression of p38 kinase in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2010;36:1445–1452. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loser DA, Shibata A, Shibata AK, Woodbine LJ, Jeggo PA, Chalmers AJ. Sensitization to radiation and alkylating agents by inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is enhanced in cells deficient in DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1775–1787. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheij M, Vens C, van Triest B. Novel therapeutics in combination with radiotherapy to improve cancer treatment: rationale, mechanisms of action and clinical perspective. Drug Resist Updat. 2010;13:29–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson L. Targeted therapies: PARP inhibitor olaparib is safe and effective in patients with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:549. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers AJ, Lakshman M, Chan N, Bristow RG. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition as a model for synthetic lethality in developing radiation oncology targets. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;20:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Tan AR. Iniparib, a PARP1 inhibitor for the potential treatment of cancer, including triple-negative breast cancer. IDrugs. 2010;13:646–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, Mortimer P, Swaisland H, Lau A, O'Connor MJ. et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carden CP, Yap TA, Kaye SB. PARP inhibition: targeting the Achilles' heel of DNA repair to treat germline and sporadic ovarian cancers. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22:473–480. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833b5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaremba T, Curtin NJ. PARP inhibitor development for systemic cancer targeting. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2007;7:515–523. doi: 10.2174/187152007781668715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C, Park M, Eulitt P, Yang C, Yacoub A, Dent P. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 modulates the lethality of CHK1 inhibitors in carcinoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:909–917. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.067199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp MC, Knafo A, Yasmeen A, Carboni JM, Gottardis MM, Pollak MN, Gotlieb WH. BMS-536924 sensitizes human epithelial ovarian cancer cells to the PARP inhibitor, 3-aminobenzamide. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Bey EA, Li LS, Kabbani W, Yan J, Xie XJ, Hsieh JT, Gao J, Boothman DA. Prostate cancer radiosensitization through poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase-1 hyperactivation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8088–8096. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Zhang YW, Ji JJ, Bonner WM, Kinders RJ, Parchment RE, Doroshow JH, Pommier Y. Histone gammaH2AX and poly(ADP-ribose) as clinical pharmacodynamic biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4532–4542. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arundel C, Glicksman A, Leith J. Enhancement of radiation injury in human colon tumor cells by the maturational agent sodium butyrate (NaB) Radiat Res. 1985;104:443–448. doi: 10.2307/3576603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackerdien Z, Michie J, Böhm L. Chromatin decondensed by acetylation shows an elevated radiation response. Radiat Res 1989 Feb;117(2):234-44. 1989;117:234–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leith J. Effects of sodium butyrate and 3-aminobenzamide on survival of Chinese hamster HA-1 cells after X irradiation. Radiat Res. 1988;114:186–191. doi: 10.2307/3577154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks P, Xu W. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Potential in cancer therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:600–608. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnin MS, Donigian JR, Cohen A, Richon VM, Rifkind RA, Marks PA, Breslow R, Pavletich NP. Structures of a histone deacetylase homologue bound to the TSA and SAHA inhibitors. Nature. 1999;401:188–193. doi: 10.1038/43710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WK, O'Connor OA, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: from target to clinical trials. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2002;11:1695–1713. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.12.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spotswood HT, Turner BM. An increasingly complex code. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110:577–582. doi: 10.1172/JCI16547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HY, Chen CS, Lin SP, Weng JR, Chen CS. Targeting histone deacetylase in cancer therapy. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:397–413. doi: 10.1002/med.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Acetylation: a regulatory modification to rival phosphorylation? EMBO J. 2000;19:1176–1179. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gennaro E, Bruzzese F, Caraglia M, Abruzzese A, Budillon A. Acetylation of proteins as novel target for antitumor therapy: review article. Amino Acids. 2004;26:435–441. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu WS, Parmigiani RB, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene. pp. 5541–5552. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Carr T, Dimtchev A, Zaer N, Dritschilo A, Jung M. Attenuated DNA damage repair by trichostatin A through BRCA1 suppression. Radiat Res. 2007;168:115–124. doi: 10.1667/RR0811.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri D, Lockman PR, Thomas FC, Hua E, Herring J, Hargrave E, Johnson M, Flores N, Qian Y, Vega-Valle E. et al. Vorinostat Inhibits Brain Metastatic Colonization in a Model of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Induces DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6148–6157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zgheib O, Huyen Y, DiTullio RJ, Snyder A, Venere M, Stavridi E, Halazonetis T. ATM signaling and 53BP1. Radiother Oncol 2005 Aug;76(2):119-22. 2005;76:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnaiyan P, Vallabhaneni G, Armstrong E, Huang SM, Harari PM. Modulation of radiation response by histone deacetylase inhibition. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2005;62:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi A, Kurland JF, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Hobbs ML, Tucker SL, Ismail S, Stevens C, Meyn RE. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Radiosensitize Human Melanoma Cells by Suppressing DNA Repair Activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4912–4922. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs JA, Nussenzweig MC, Nussenzweig A. Chromatin dynamics and the preservation of genetic information. Nature. 2007;447:951–958. doi: 10.1038/nature05980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis TC, Harikrishnan KN, El-Osta A. The histone deacetylase inhibitor, Trichostatin A, enhances radiation sensitivity and accumulation of gamma H2A.X. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2005;4:787–793. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.7.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng L, Cuneo KC, Fu A, Tu T, Atadja PW, Hallahan DE. Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitor LBH589 Increases Duration of {gamma}-H2AX Foci and Confines HDAC4 to the Cytoplasm in Irradiated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11298–11304. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YL, Lee MY, Pui NNM. Epigenetic therapy using the histone deacetylase inhibitor for increasing therapeutic gain in oral cancer: prevention of radiation-induced oral mucositis and inhibition of chemical-induced oral carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1387–1397. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikrishnan KN, Karagiannis TC, Chow MZ, El-Osta A. Effect of valproic acid on radiation-induced DNA damage in euchromatic and heterochromatic compartments. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:468–476. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.4.5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Zhang T, Teng Z, Zhang R, Wang J, Mei Q. Sensitization to gamma-irradiation-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:823–831. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Shin J, Kim I. Susceptibility and radiosensitization of human glioblastoma cells to trichostatin A, a histone deacetylase inhibitor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:1174–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnaiyan P, Cerna D, Burgan WE, Beam K, Williams ES, Camphausen K, Tofilon PJ. Postradiation Sensitization of the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Valproic Acid. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5410–5415. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camphausen K, Cerna D, Scott T, Sproull M, Burgan W, Cerra M, Fine H, Tofilon P. Enhancement of in vitro and in vivo tumor cell radiosensitivity by valproic acid. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:380–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baschnagel A, Russo A, Burgan WE, Carter D, Beam K, Palmieri D, Steeg PS, Tofilon P, Camphausen K. Vorinostat enhances the radiosensitivity of a breast cancer brain metastatic cell line grown in vitro and as intracranial xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1589–1595. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter H, Kimpe M, Isebaert S, Nuyts S. A systematic assessment of radiation dose enhancement by 5-Aza-2'-deoxycytidine and histone deacetylase inhibitors in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly W, Marks P. Drug insight: Histone deacetylase inhibitors--development of the new targeted anticancer agent suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:150–157. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis TC, Harikrishnan KN, El-Osta A. Disparity of histone deacetylase inhibition on repair of radiation-induced DNA damage on euchromatin and constitutive heterochromatin compartments. Oncogene. 2007;26:3963–3971. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli JA, Hellman S. Editorial: Hypoxic cell radiosensitizers. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1399–1400. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197606172942511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TL, Wasserman TH, Johnson Rj, Gomer CJ, Lawrence GA, Levine ML, Sadee W, Penta JS, Rubin DJ. The hypoxic cell sensitizer programme in the United States. Br J Cancer Suppl. 1978;3:276–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff P, Altmeyer A, Dumont F. Radiosensitising agents for the radiotherapy of cancer: advances in traditional and hypoxia targeted radiosensitisers. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;19:643–662. doi: 10.1517/13543770902824172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive PL, Banath JP, Sinnott LT. Phosphorylated histone H2AX in spheroids, tumors, and tissues of mice exposed to etoposide and 3-amino-1,2,4-benzotriazine-1,3-dioxide. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5363–5369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardman P, Rothkamm K, Folkes LK, Woodcock M, Johnston PJ. Radiosensitization by nitric oxide at low radiation doses. Radiat Res. 2007;167:475–484. doi: 10.1667/RR0827.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palayoor ST, Mitchell JB, Cerna D, Degraff W, John-Aryankalayil M, Coleman CN. PX-478, an inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, enhances radiosensitivity of prostate carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2430–2437. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson AV, Ferry DM, Edmunds SJ, Gu Y, Singleton RS, Patel K, Pullen SM, Hicks KO, Syddall SP, Atwell GJ. et al. Mechanism of action and preclinical antitumor activity of the novel hypoxia-activated DNA cross-linking agent PR-104. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3922–3932. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JW, Chernikova SB, Kachnic LA, Banath JP, Sordet O, Delahoussaye YM, Treszezamsky A, Chon BH, Feng Z, Gu Y. et al. Homologous recombination is the principal pathway for the repair of DNA damage induced by tirapazamine in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:257–265. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economopoulou M, Langer HF, Celeste A, Orlova VV, Choi EY, Ma M, Vassilopoulos A, Callen E, Deng C, Bassing CH. et al. Histone H2AX is integral to hypoxia-driven neovascularization. Nat Med. 2009;15:553–558. doi: 10.1038/nm.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Aardweg G, Hopewell J. The kinetics of repair for sublethal radiation-induced damage in the pig epidermis: an interpretation based on a fast and a slow component of repair. Radiother Oncol. 1992;23:94–104. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(92)90340-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume S, Myers R. An unexpected effect of hyperthermia on the expression of X-ray damage in mouse skin. Radiat Res. 1984;97:186–199. doi: 10.2307/3576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers HR, Kathryn AM. The kinetics of recovery in irradiated colonic mucosa of the mouse. Cancer. 1974;34:896–903. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197409)34:3+<896::AID-CNCR2820340717>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haagen J, Krohn H, Röllig S, Schmidt M, Wolfram K, Dörr W. Effect of selective inhibitors of inflammation on oral mucositis: Preclinical studies. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörr W, Kummermehr J. Accelerated repopulation of mouse tongue epithelium during fractionated irradiations or following single doses. Radiother Oncol. 1990;17:249–259. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(90)90209-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr W, Heider K, Spekl K. Reduction of oral mucositis by palifermin (rHuKGF): Dose-effect of rHuKGF. Int J Radiat Biol. 2005;81:557–565. doi: 10.1080/09553000500196136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JE, Roch-Lefevre SH, Mandina T, Garcia O, Roy L. Induction of gamma-H2AX foci in human exfoliated buccal cells after in vitro exposure to ionising radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:752–759. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2010.484476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhogal N, Kaspler P, Jalali F, Hyrien O, Chen R, Hill RP, Bristow RG. Late residual gamma-H2AX foci in murine skin are dose responsive and predict radiosensitivity in vivo. Radiat Res. 2010;173:1–9. doi: 10.1667/RR1851.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qvarnstrom OF, Simonsson M, Johansson KA, Nyman J, Turesson I. DNA double strand break quantification in skin biopsies. Radiother Oncol. 2004;72:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qvarnström O, Simonsson M, Johansson K, Nyman J, Turesson I. DNA double strand break quantification in skin biopsies. Radiother Oncol 2004 Sep;72(3):311-7. 2004;72:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sak A, Grehl S, Erichsen P, Engelhard M, Grannaß A, Levegrün S, Pöttgen C, Groneberg M, Stuschke M. gamma-H2AX foci formation in peripheral blood lymphocytes of tumor patients after local radiotherapy to different sites of the body: Dependence on the dose-distribution, irradiated site and time from start of treatment. Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83:639–652. doi: 10.1080/09553000701596118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogrlbny I, Koturbash I, Tryndyak V, Hudson D, Stevenson SML, Sedelnikova O, Bonner W, Kovalchuk O. Fractionated low-dose radiation exposure leads to accumulation of DNA damage and profound alterations in DNA and histone methylation in the murine thymus. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:553–561. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothkamm K, Horn S. gamma-H2AX as protein biomarker for radiation exposure. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2009;45:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T, Kang I, Wheeler D, Lindquist R, Papallo A, Sabatini D, Golland P, Carpenter A. CellProfiler Analyst: data exploration and analysis software for complex image-based screens. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böcker W, Iliakis G. Computational Methods for analysis of foci: validation for radiation-induced gamma-H2AX foci in human cells. Radiat Res. 2006;165:113–124. doi: 10.1667/rr3486.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YN, Lavaf A, Huang D, Peters S, Huq R, Friedrich V, Rosenstein BS, Kao J. Development of an Automated gamma-H2AX Immunocytochemistry Assay. Radiat Res. 2009;171:360–367. doi: 10.1667/RR1349.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garty G, Chen Y, Salerno A, Turner H, Zhang J, Lyulko O, Bertucci A, Xu Y, Wang H, Simaan N. et al. The RABIT: a rapid automated biodosimetry tool for radiological triage. Health Phys. 2010;98:209–217. doi: 10.1097/HP.0b013e3181ab3cb6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobrich M, Rief N, Kuhne M, Heckmann M, Fleckenstein J, Rube C, Uder M. In vivo formation and repair of DNA double-strand breaks after computed tomography examinations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8984–8989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501895102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothkamm K, Balroop S, Shekhdar J, Fernie P, Goh V. Leukocyte DNA Damage after Multi†"Detector Row CT: A Quantitative Biomarker of Low-Level Radiation Exposure1. Radiology. 2007;242:244–251. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2421060171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]