Abstract

The specification of left-right asymmetry is an evolutionarily conserved developmental process in vertebrates. The interplay between two TGFβ ligands, Derrière/GDF1 and Xnr1/Nodal, together with inhibitors such as Lefty and Coco/Cerl2, have been shown to provide the signals that lead to the establishment of laterality. However, molecular events leading to and following these signals remain mostly unknown. We find that APOBEC2, a member of the cytidine deaminase family of DNA/RNA editing enzymes, is induced by TGFβ signaling, and that its activity is necessary to specify the left-right axis in Xenopus and zebrafish embryos. Surprisingly, we find that APOBEC2 selectively inhibits Derrière, but not Xnr1, signaling. The inhibitory effect is conserved, as APOBEC2 blocks TGFβ signaling, and promotes muscle differentiation, in a mammalian myoblastic cell line. This demonstrates for the first time that a putative RNA/DNA editing enzyme regulates TGFβ signaling, and plays a major role in development.

Keywords: APOBEC2, left-right, muscle, TGFβ, Xenopus

INTRODUCTION

In vertebrates, left-right asymmetry is manifested anatomically by the selective folding and positioning of a subset of internal organs, like the heart and the gut. The emergence of laterality is also obvious during early development through genes that are expressed specifically in the left lateral plate mesoderm, such as the secreted factors Nodal and Lefty, both members of the TGFβ signaling molecules, and the transcription factor Pitx2. However, the key symmetry breaking event occurs before the left side specific expression of Nodal, Lefty and Pitx2, and involves signals emanating from the posterior mesoderm portion of the late organizer tissue in frogs at the end of gastrulation, and similar organizing centers in other vertebrates (Kupffer's vesicle in fish and the node in birds and mammals; Essner et al., 2002; Schweickert et al., 2007; Shook et al., 2004). These early signals from the posterior mesoderm are subsequently transferred to the lateral plate mesoderm. The key event in breaking symmetry is mediated by unidirectional flow mediated by cilia (Essner et al., 2005; Hirokawa et al., 2006; Schweickert et al., 2007). In the chick it involves cell migration (Gros et al., 2009), and in frogs long range diffusion of the ligand has been invoked (Tanaka et al., 2007). Regardless of the mechanism, however, initial signals form the first organizing center (posterior mesoderm) in turn generate a second signaling center (left lateral plate mesoderm) to ultimately convey right versus left positional information, guiding the appropriate folding and positioning of the internal organs (Bisgrove and Yost, 2006; Hirokawa et al., 2006; Lee and Anderson, 2008; Levin, 2005; Mercola, 2003; Raya and Belmonte, 2006; Shiratori and Hamada, 2006; Speder et al., 2007; Whitman, 2001).

The early signals emanating from the first organizing center in posterior mesoderm result from an interplay between TGFβ ligands and inhibitors. Two ligands: Xenopus-nodal-related-1 (Xnr1)/nodal and Derrière/GDF1, together with their inhibitor Coco/Dante/Cerl2, mediate signaling (Hashimoto et al., 2004; Marques et al., 2004; Pearce et al., 1999; Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007). Interestingly, Derrière and Xnr1 ligands exist as both homo- and heterodimer, share the same set of inhibitors, and are part of a positive feed back loop inducing each other's expression (Eimon and Harland, 2002; Tanaka et al., 2007). Moreover, in addition to Xnr1, both Derrière and Coco activity were required in the posterior mesoderm for correct left-right axis determination (Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007). Derrière controls the levels of Xnr1 expression and Coco acts as an inhibitor of both ligands. Ultimately, the balance between extracellular inhibitors and activators establishes differential thresholds of signaling on each side of the embryo. To trigger nodal-type TGFβ signaling, ligands bind and activate receptor complexes that consist of two type I receptors, ALK4 and ALK7, and two type II receptors, ActRIIA and ActRIIB. The receptor complex also requires participation of co-receptors of either EGF-CFC type such as XCR/Cripto, or TMMEF1 (Cheng et al., 2003; Dorey and Hill, 2006; Gritsman et al., 1999; Onuma et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2002; Yeo and Whitman, 2001). From the three XCR co-receptors that are expressed during early Xenopus embryogenesis, only XCR2 is present at the time when left-right asymmetry is specified. Activated receptors in turn activate the signal transducers Smad2/3. Consistent with their involvement, intracellular factors that interfere with ALK4 and Smad2/3 interaction, such as Ttrap, have shown to influence the right-left axis (Esguerra et al., 2007). Smad2/3 associate with Smad4, translocate to the nucleus, and regulate transcription of specific genes in cooperation with other transcription factors. In left-right axis determination, different thresholds of Xnr1 and Derrière signaling on each side lead to different transcriptional output segregating left cell fates from right by selective expression of genes such as Pitx2 on the left lateral plate mesoderm, setting up the second organizing center (Bisgrove and Yost, 2001; Brand, 2003; Levin, 2005; Wright, 2001).

While the organizing centers and the molecular nature of the signals involved in the establishment of laterality have been characterized, events occurring downstream of signaling remain poorly understood. Performing a global analysis of genes that are regulated by Derriere in the posterior mesoderm, we find unexpectedly that APOBEC2 (Anant et al., 2001; Liao et al., 1999), an evolutionarily conserved member of the cytidine deaminases family of proteins, is induced by TGFβ signaling, and has a direct involvement in left-right specification. We show that APOBEC2 activity is necessary for left-right specification by selectively inhibiting Derrière but not Xnr1 signaling in Xenopus. In addition, APOBEC2 is required as a TGFβ inhibitor for the differentiation of a mammalian myoblastic cell line. These experiments highlight the role of an unexpected player in the context of TGFβ signaling pathway in general, and a previously unknown biological function for APOBEC2 in the context of left-right axis determination during vertebrate embryogenesis.

RESULTS

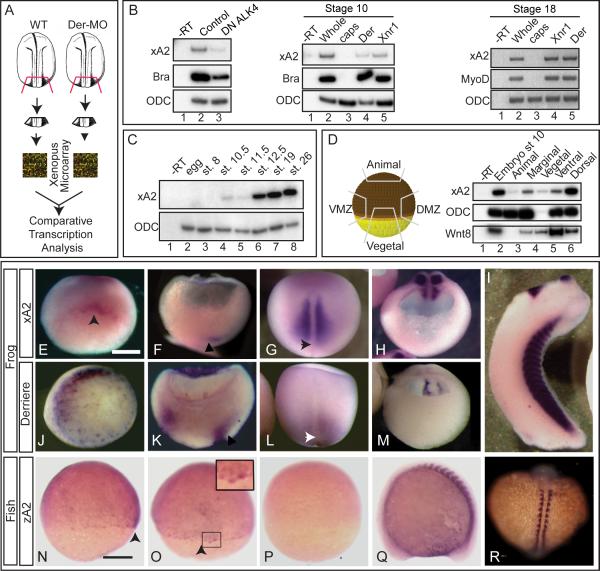

APOBEC2, a target of TGFβ signaling, is expressed in the organizer

The activity of the TGFβ ligand Derrière is necessary for the proper development of laterality during early vertebrate embryogenesis (Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007). To identify the molecular network underlying right-left specification downstream of Derrière signaling, we performed microarray analysis comparing mRNA expression between wild type and Derrière-depleted embryonic explants (Figure 1A). This analysis led to the identification of a number of Derrière-regulated genes (Supplementary Data at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/geo, accession numbers GSM349689, GSM349690, GSE13882; and Table S1). Surprisingly, we find that Xenopus laevis APOBEC2 (xA2, Genbank accession #BC074467, Supplementary Figure 1A), the ortholog of the mammalian APOBEC2/ARCD-1 DNA/RNA editing enzyme (Anant et al., 2001), is down-regulated upon Derrière depletion. Because editing enzymes have not been previously associated with TGFβ signaling, we followed on the molecular and embryonic characterization of xA2 activity. Decreased xA2 expression upon Derrière depletion implied that signaling by this ligand induces xA2. RT-PCR analysis confirmed that xA2 was moderately decreased in Derrière-depleted embryos at both stage 12 and 18 (Supplementary Figure 1B, C), confirming the microarray result, and strongly decreased in embryos overexpressing a dominant-negative form of the nodal-specific type 1 receptor ALK4 (DN ALK4(KR), Figure 1B, Yeo and Whitman, 2001). In addition, overexpression of Derrière and Xnr1 induced and maintained xA2 expression in stage 10 and 18 ectodermal explants (Figure 1B). Together, these experiments indicate that xA2 is a target of TGFβ signaling.

Figure 1. APOBEC2 is a target of TGFβ signaling coexpressed with derrière in Xenopus embryos.

A. Strategy for identification of genes regulated by derrière. Posterior dorsal fragments from wild-type and derrière -MO (Der-MO)-injected embryos were isolated at stage 18. B. TGFβ signaling and xA2 expression. Overexpression of a dominant negative type 1 receptor (DN ALK4) reduces expression of marginal xA2 in stage 10 whole embryos (left panel). Overexpressed Xnr1 (30 pg) and derrière (100 pg) RNA induce xA2 expression in stage 10 (central panel) and 18 (right side panel) animal caps. RT-PCR for xA2, MyoD, and Brachyury as markers of mesoderm induction, and ODC as loading control. C. Timing of xA2 expression. RT-PCR of embryos collected at the indicated developmental stages. D. Spatial expression of xA2 in stage 10 embryos. RT-PCR of embryonic explants (VMZ: ventral marginal zone; DMZ: dorsal marginal zone). E-M. Comparative expression of xA2 and derrière. In situ hybridization for xA2 (E-I), and derrière (JM) expression. (E, J) Stage 10 vegetal-dorsal views, arrowhead indicates the forming dorsal lip; (F, K) Stage 11 dorso-ventral sections (dorsal to the right). Arrowheads indicate recently involuted mesoderm; (G, L) dorsal views (anterior up). Arrowheads indicate the blastopore; (H, M) Stage 16 transversal sections, posterior fragments (dorsal is up). (I) Stage 32 lateral view. Overlap between xA2 and derrière occurs at stage 10 (dorsal marginal), stage 11 (involuted mesoderm), and stage 16 (paraxial mesoderm). N-R. Expression of zebrafish A2 (zA2). (N, O, P) 75% epiboly, in (N) lateral view (dorsal to the right) and (O) dorsal views. The arrowheads in N and O indicate the shield. (Q-R) 14 somite stage embryo. The inset in O (two fold magnification) shows shield cells with nuclear stain. (Q) Lateral view, anterior to the left, (R) dorsal view (anterior up). (P) Embryo stained with the sense probe as negative control. The bar in (E) indicates 0.3 mm, and in (N) 0.1 mm.

To begin the characterization of xA2 function, we determined its spatio-temporal pattern of expression during embryogenesis. RT-PCR analysis revealed that expression of xA2 begins weakly at the onset of gastrulation, and then increases at neurulation (Figure 1C). The weak expression in gastrulation occurs mostly in dorsal marginal cells, including the late organizer (Figure 1D, E). xA2 expression is confined to the paraxial somitic mesoderm during neurulation (Figure 1G, and H) as well as the heart and cement gland at tailbud stages (Figure 1I). Expression pattern of zebrafish A2 (zA2) displayed a similar pattern with higher levels of zA2 RNA in the shield (the equivalent of the organizer, Figure 1N, O), and subsequent expression in the somites and heart, as reported (Figure 1Q, and R; Mikl et al., 2005; Thisse et al., 2004). In addition, and consistent with xA2 being a target for TGFβ signaling, we find that the expression pattern of xA2 overlaps with the expression domains of Derrière during gastrula and neurula stages, when the specification of laterality occurs (Figure 1J-M; Sun et al., 1999).

A2 activity is necessary for the establishment of left-right axis

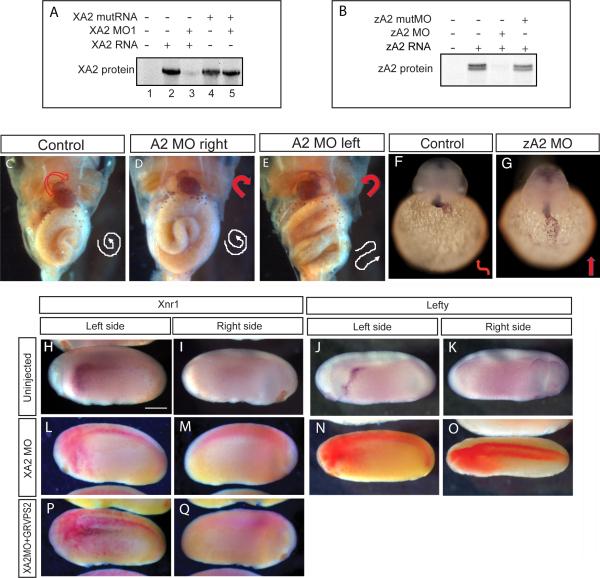

To investigate a possible role of xA2 in left-right specification during early development, we performed loss-of-function experiments using translation-blocking morpholinos (xA2 MO1 and 2, Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure 2A). Both MOs had the same phenotype, and in subsequent experiments we used xA2 MO1 (henceforth named xA2 MO). xA2 MO, along with GFP RNA used as lineage tracer, was microinjected to target either the right or left paraxial mesoderm (PM, see Materials and Methods, and Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007). During normal development, the heart folds to the right, and the gut loops counterclockwise (Figure 2C). Random deviation from this pattern is called heterotaxia. Injected embryos were examined at stage 48 for heart rotation and intestinal looping as morphological readout for laterality. Heterotaxia was detected when xA2 protein was depleted on the left, but not the right side (Figure 2D, E, and Table 1). No effect was seen on axial development for the amount of MO used in this study (10 ng, Supplementary Figure 2C, D). Consistently, examination of molecular markers specific for the left side at stage 23-24 revealed that depletion of xA2 on the left blocked expression of Xnr1 and Lefty in the left LPM (Figure 2H-Q and Table 2). As left LPM markers are induced by early signals emanating during neurula from the posterior paraxial mesoderm (Ohi and Wright, 2007), we examined the effect of xA2 MO on the posterior PM. We find that reduction of xA2 activity leads to a decrease in Xnr1 and an anterior expansion of Derrière expression, as seen in in situ hybridization of posterior poles of stage 18 embryos (Figure 3C-H, internal views, anterior is up, left side of the embryo is on the right side of each picture), and confirmed in RT-PCR (Supplementary Figure 3J). Thus, disturbance in the balance of Derrière and Xnr1 signaling early in the posterior PM is the probable cause of the laterality phenotype. Finally, a left-right phenotype was observed in zebrafish embryos when MOs targeting zA2 were used (zA2 MO, Figure 2F,G, Supplementary Figure 2B, and Table 1). A slight developmental delay of 1 - 2 hours was noted in zA2MO-injected embryos during somitogenesis stages, whereas in situ hybridization with a cmlc2 probe revealed a lack of heart looping in zA2MO-injected embryos even 5 – 6 hours after obvious looping in uninjected embryos. Further, looping defects were also observed after 48 hpf (data not shown), indicating that the role of xA2 in the context of right-left specification is evolutionarily conserved.

Figure 2. Effect of APOBEC2 protein depletion in Xenopus and zebrafish.

A, B. Inhibition of in vitro translation by xA2 MO (A) and zA2 MO (B). C-E. Left side depletion of xA2 protein randomizes the left-right axis in Xenopus. Embryos injected on the left side with 10 ng xA2 MO were stained for light meromyosin at stage 46. (C) control embryo; (D) right side MO injection normal embryo; (E) left side MO injection, inverted heart and abnormally folded intestine. Arrows indicate the direction of the heart outflow tract and intestinal looping. F-G. Depletion of zA2 protein prevents heart looping in zebrafish. In situ hybridization with cmlc2 antisense probe for heart muscle on 36-40 hpf embryos. Arrows indicate ventricular looping. H-Q. xA2 depletion blocks the left side nodal signal. in situ hybridization for Xnr1 (H, I, L, M, P, Q), and Lefty (J, K, N, O) in purple, and injected LacZ RNA as tracer (L-Q) in red. Wild-type expression of Xnr1 (H) and Lefty (J) in the left lateral plate mesoderm was inhibited by injection of xA2 MO in the left paraxial mesoderm (L, N). Left side expression of Xnr1 was rescued by coinjection of GRVP16SMAD2Δ3 RNA (25 pg RNA, induced at stage 16; P). All views are lateral, except (O) (dorsal), anterior to the left. Embryos are stage 23 (Xnr1), and stage 24 (Lefty). The bar in (H) represents 0.3 mm.

Table 1. Phenotype of A2 protein depletion in Xenopus and zebrafish.

Xenopus Injections at the 4 cell stage were targeted at the paraxial mesoderm on the indicated side. Embryos were scored for heart rotation and intestinal looping at stage 46. All degrees of deviation from the normal right side looping of the heart were included in the inversion category. Correct detection of the injected side was highlighted by coinjected GFP. XA2 DNA (100 pg), GRVP16hSMAD2Δ3 RNA (25 pg) and derrrière MO (0.1 ng), but not Xnr1 RNA (1 pg), rescued the left-right axis. Smad2 was activated with dexamethasone at stage 11 or 16. For rescue experiments, MO alone was compared to MO+rescue. Derrière MO was compared to wild-type. Zebrafish. Embryos were injected with 2 ng Control or ZA2 MO. Heart looping was scored at 36-48 hpf by in situ hybridization with cmlc2 or by peroxidase immunostaining with the MF20 antibody. Statistical significance was determined with the Chi-square test.

| Injection | Normal (%) | Inversions (%) (heart and/or intestine) | Heart inversions (%) | Total embryos | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 95.5 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 176 | |

| XA2 MO Left | 40 | 60 | 44 | 108 | ≤0.001 |

|

XA2 MO Right

|

84 | 10 | 2.3 | 43 | NS |

| Rescue (left side): | |||||

| MO+XA2 DNA | 75 | 25 | 25 | 55 | ≤0.001 |

| MO+GRVP16Smad2+Dex 16 | 64 | 36 | 11 | 54 | ≤0.05 |

| MO+GRVP16Smad2+Dex 10 | 34 | 66 | 43 | 49 | NS |

| MO+Xnr1 RNA | 30 | 70 | 38 | 44 | NS |

| XA2 MO+Der MO | 95 | 5 | 5 | 38 | ≤0.001 |

|

Der MO

|

95 | 5 | 0 | 40 | NS |

| GRVP16Smad2 Left | 86.5 | 13.5 | 9 | 44 | NS |

| GRVP16Smad2+Dex 11 | 41.5 | 58.5 | 54 | 42 | ≤0.0001 |

| GRVP16Smad2+Dex 16 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 40 | N |

| Normal (right loop) (%) | Reduced loop (%) | Inverted (left loop) (%) | Total embryos | ||

| Controls Zebrafish | 90 | 5 | 5 | 40 | |

| Control MO | 84 | 9 | 7 | 43 | NS |

| ZA2 MO | 35 | 55 | 10 | 20 | <0.0001 |

Table 2. XA2 depletion prevents expression of laterality markers.

Double in situ hybridization for Xnr1 (stage 23) or Lefty (stage 24) and coinjected LacZ as lineage tracer. All injections were targeted at the paraxial mesoderm, unless specified otherwise. (A) Xnr1 expression in left LPM is blocked by xA2 MO (10 ng) and rescued by coinjection with GRVP16hSMAD2Δ3, induced at stage 16. (B) Lefty is blocked by xA2 depletion and can be rescued by overexpression of Xnr1 (1 pg RNA) when injected separately in the LPM, but not when coinjected with xA2 MO in PM. Statistical significance was determined with the Chi-square test. MO and xA2 RNA samples were compared to controls, and rescues were compared to the MO sample.

| Injection | Normal (%) | Absent (%) | Bilateral (%) | Inverted (%) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Xnr1 | ||||||

| Control | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 53 | |

| XA2 MO Left | 22 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 45 | ≤0.0001 |

| MO+GRVPhSmad2 | 60 | 33 | 7 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.05 |

| XA2 RNA Left | 45 | 48 | 0 | 7 | 31 | ≤0.0001 |

| B. Lefty | ||||||

| Control | 97 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 56 | |

| XA2 MO Left | 36 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 50 | ≤0.0001 |

| MO+Xnr1 RNA (PM) | 11 | 89 | 0 | 0 | 35 | NS |

| MO(PM)+Xnr1(LPM) | 93 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 26 | ≤0.001 |

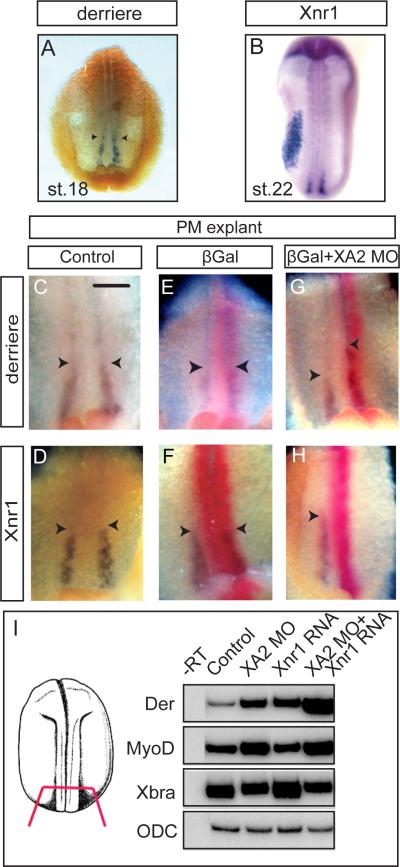

Figure 3. xA2 depletion inhibits Xnr1 and increases derrière expression in posterior mesoderm.

A-H. In situ hybridization for derrière (stage 18, A) and Xnr1 (stage 22, B), and double in situ hybridization for derrière (C, E, G), or Xnr1 (D, F, H), purple, and LacZ RNA coinjected as tracer (red). C-H are internal views of posterior dorsal fragments, anterior side up, of stage 18 embryos. The left side of each panel is the right side of each embryo. Xnr1 expression was inhibited by xA2 MO (n=36; H). Expression of derrière was expanded in anterior direction on the side injected with xA2 MO (n=33, arrowheads in G). The bar in C represents 0.1 mm. I. xA2 depletion synergizes with low levels of overexpressed Xnr1 RNA. RT-PCR of posterior poles injected bilaterally with xA2 MO (10 ng), Xnr1 RNA (1 pg), or both. The combination increased derrière and MyoD, but not Xbra expression.

To address the specificity of the xA2 MO phenotype and to position the input of xA2 in the pathway, we performed rescue experiments. xA2 MO was co-injected with DNA encoding xA2 lacking the MO binding site, or mRNA for an inducible Smad2 (GRVP16hSmad2Δ3; (Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007). GRVP16hSmad2Δ3 protein is retained in the cytoplasm until addition of dexamethasone (Dex) to the embryos. Coinjection of xA2 MO with the mutant xA2 DNA rescued the heterotaxia phenotype (Table 1), providing evidence for specificity. Additionally, coinjection of xA2 MO with GRVP16hSmad2Δ3 RNA, followed by Dex induction at neurula stages, rescued both the left-right asymmetry, and expression of molecular markers in the left LPM (Figure 2P; Table 1). The fact that induction of Smad2 was sufficient to rescue the phenotype when activated at neurula stages suggests that the rescue is not due to an indirect effect on TGFβ signaling. This experiment establishes that xA2 activity is required upstream of Smad2, in the context of left-right specification in vivo. Taken together, this evidence demonstrates that: (i) xA2 activity is required on the left side of the embryos for proper establishment of laterality and expression of left-side-specific markers; (ii) xA2 MO effect on LPM gene expression is due to interference with early posterior PM signals; (iii) the activity of xA2 in the context of left -right specification appears to be conserved between teleosts and amphibians.

To address the molecular mechanism of the effect of xA2 depletion, we tried to rescue the left-right phenotype with TGFβ ligands. Coinjection of xA2 MO and Xnr1 RNA directed at the left PM failed to rescue the xA2 depletion phenotype, including the left side expression of Lefty (Table 1, 2; Supplementary Figure 3 B, C). Instead, embryos had short trunks and tails, and blastopore closure defects (Supplementary Figure 3A, and data not shown). However, when Xnr1 RNA was injected separately from paraxial xA2 MO, and directed at the left LPM, it did rescue the xA2 depletion phenotype (Table 2). These results indicate that the defect in TGFβ signaling causing the phenotype of xA2 depletion could be more complex than the absence of nodal/Xnr1 expression in posterior paraxial mesoderm, and that the lateral plate mesoderm retained the ability to respond to local nodal signals. To explain this unexpected result, we compared gene expression in posterior poles of neurula stage embryos with injections directed at the PM with xA2 MO alone, or coinjections of MO and Xnr1 RNA (Figure 3I, and Supplementary Figure 3 D-I). derrière and MyoD, a known target of TGFβ signaling in paraxial mesoderm (reviewed in (Dale, 1997; Green, 2002; Schier and Talbot, 2005; Smith, 1995), but not Brachyury, which is expressed in the notochord (Smith et al., 1991), were increased in xA2-depleted embryos, and had even higher levels when Xnr1 RNA and xA2 MO were associated. This apparent synergy between xA2 MO and an overexpressed TGFβ ligand suggests that depletion of xA2 could increase TGFβ signaling in posterior mesoderm.

The cells that will form the posterior PM are exposed to sequential TGFβ signals during Xenopus development, starting with the maternal Vg1, followed by multiple Xnr ligands and Derrière during blastula, and again Derrière during gastrula. To understand which TGFβ signal is affected by xA2 depletion, and its timing, we again used the dexamethasone-inducible Smad2 construct, GRVP16hSmad2Δ3, in coinjections with xA2 MO directed at the PM. Activation of this construct in A2-depleted embryos at neurula stage restored the left-right axis and expression of Xnr1 in the left LPM, indicating that the inducible Smad2 restored the posterior TGFβ signal decreased by the reduction in Xnr1 expression. In contrast, activation in gastrula did not rescue the left-right phenotype and produced the same trunk defects seen with Xnr1 RNA coinjection (Table 1 and data not shown). These results indicate that the phenotypic synergy between xA2 depletion and TGFβ overexpression described above probably results from molecular interactions that occur no later than the gastrula stage, when xA2 and derrière expressions overlap (Figure 1 F, K). Together, the synergy between xA2 depletion and TGFβ activity, the timing of the effect, and expression data suggest that xA2 depletion increases Derrière activity at gastrula stage. This leads to defects in posterior patterning at neurula stage, including the absence of Xnr1 expression and subsequent left-right specification defects.

The hypothesis that an increase in Derrière activity is the cause of the xA2 phenotype was tested directly by partially depleting the Derrière protein. An amount of Derrière MO that had no effect by itself rescued the left-right phenotype of xA2 depletion in coinjections targeted at the left PM (Table 1). In addition, we found that overexpression of the inducible Smad2 construct alone caused a left-right phenotype when activated in gastrula (stage 11), but not neurula (stage 16), (Table 1), confirming that increased TGFβ signaling in cells fated to become left PM can by itself produce left-right defects.

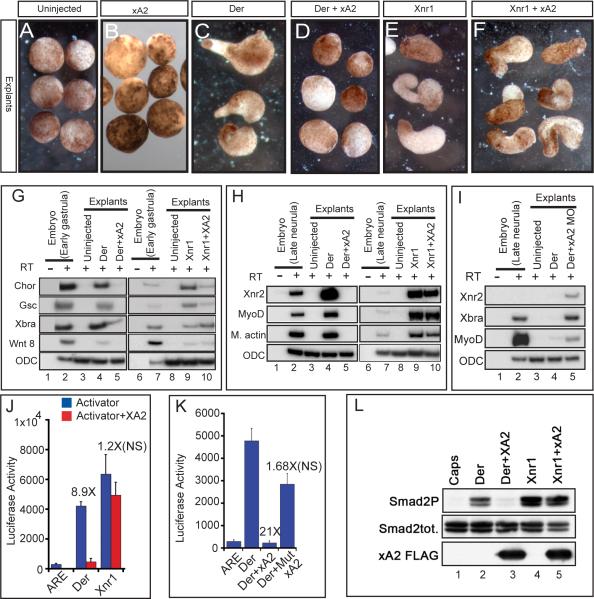

xA2 selectively inhibits Derrière, but not Xnr1 signaling

To begin the molecular and biochemical characterization of xA2 activity, we challenged the mesoderm-inducing activity of both Derrière and Xnr1 in animal cap explants. These explants, which give rise solely to epidermis when cultured alone (Figure 4A), can be induced by TGFβ ligands, including Derrière and Xnr1, to form mesoderm (reviewed in (Harland and Gerhart, 1997) and to elongate. We find that expression of xA2 alone did not change the morphology of animal caps (Figure 4B) or induce any germ layer-specific marker (not shown), suggesting that while xA2 is a target of TGFβ signaling, it has no ability to induce new cell types on its own. Interestingly, however, xA2 RNA overexpression selectively inhibited both the elongation and the induction of mesodermal markers induced by Derrière, but not by Xnr1 (Figures 4D, F, G, H). In agreement with the inhibitory effect of xA2 on Derrière, coinjection of xA2 MO with a low amount of Derrière RNA increased the expression of mesodermal fate genes (Figure 4I), and overexpression of xA2 RNA in the left PM produced a left-right phenotype by blocking Xnr1 expression in the left LPM (Table 2). Transcriptional assays confirmed these results independently. Derrière, but not Xnr1 induction of the Smad2 responsive promoter, ARE-lux (Liu et al., 1997), was strongly reduced when xA2 was co-expressed (Figure 4J). The transcriptional effect was specific for the TGFβ pathway, as xA2 did not inhibit activation of the siamois reporter gene (Brannon et al., 1997) by Wnt8 (Supplementary Figure 3L). We also generated a triple mutant of the putative enzymatic site (E102Q, C130S, and C132S, Supplementary Figure 1A). Although the mutant was as stably expressed as the wild type (Supplementary Figure 3K), it did not change the Derrière-mediated transcriptional activation of ARE-lux in a statistically significant way (Figure 4K), failed to rescue the XA2 MO left-right phenotype when expressed at low levels, and did not cause a left-right phenotype when expressed alone at high level on the left side (Table 3). Taken together, these experiments suggest that xA2 needs its deaminase domain for the left-right function and for inhibiting Derrière signaling upstream of transcriptional response. Examination of the state of Smad2 activation revealed that C-terminal phosphorylation of endogenous Smad2 induced by derrière, but not Xnr1, is strongly inhibited by co-expression of xA2 (Figure 4L). Thus, inhibition of Smad2-dependent mesoderm induction, transcriptional activation, and C-terminal phosphorylation, suggests that xA2 regulates the TGFβ pathway upstream of Smad2.

Figure 4. APOBEC2 is a TGFβ inhibitor in Xenopus.

A-F. xA2 prevents cap elongation induced by derrière but not Xnr1. RNAs were injected in the animal poles of 2 cell stage embryos (xA2 2ng, derrière 200pg, Xnr1 30pg). Caps were explanted at stage 10 and cultured to stage 18. G, H. Expression of xA2 RNA represses derrière-, but not Xnr1-dependent gene induction. RT-PCR of early gastrula (G) and late neurula (H) stage animal caps injected with derrière RNA (200 pg), or Xnr1 RNA (20 pg), with or without xA2 RNA (2 ng). I. xA2 depletion increased mesoderm induction by derrière RNA. RT-PCR for mesodermal genes (Xnr2, Xbra and MyoD), with ODC as loading control, in stage 18 animal caps injected with derrière RNA (100 pg) and xA2 MO (10 ng). J. xA2 specifically inhibits Derrière-induced transcription. Transcription assays for the Activin/nodal reporter ARE. Transcriptional inhibition by xA2 was statistically significant with derrière (200 pg RNA), but not with Xnr1 (20 pg RNA). K. An intact putative deaminase domain is required for the inhibitory activity of xA2. Wild-type, but not the triple mutant xA2 (Mut xA2, 2 ng RNA), inhibited transcription induced by derrière (200 pg RNA). The difference in transcriptional activity induced by Derrière alone vs. Derrière+xA2 wild-type was statistically significant (P<0.001), while that vs. the mutant xA2 was not. L. xA2 blocks the C-terminal phosphorylation of endogenous Smad2/3 induced by derrière. Western blot for total Smad2/3 and C-terminally phosphorylated Smad2/3 in stage 10.5 animal caps. No effect was seen on total Smad2/3 protein levels.

Table 3. The catalytic domain of XA2 is required for the left-right phenotype.

A. Wild-type, but not a catalytic domain mutant (Mut XA2 DNA), rescues the phenotype of XA2 depletion on the left side. Embryos were injected with XA2 MO (2 ng), with or without wild-type or Mut XA2 DNA (100 pg) and GFP RNA for correct localization. B. Overexpression of wild-type XA2 RNA (2 ng) has a stronger effect on left-right axis determination than the mutant RNA. Statistical significance was determined with the Chi-square test. MO and wild-type RNA injections were compared to controls, the DNA rescues were compared to MO injections, and the mutant RNA injection was compared to control (NS) and wild-type RNA injection (P<0.0001).

| Injection | Normal (%) | Inversions (%) (heart or intestine) | Heart inversions (%) | Total embryos | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 97 | 3 | 1 | 69 | |

| A. XA2 MO Left | 53 | 47 | 44 | 45 | ≤0.0001 |

| + wt XA2 DNA | 74 | 26 | 17 | 58 | ≤0.05 |

| + Mut XA2 DNA | 40 | 60 | 46 | 56 | NS |

| B. wt RNA Left | 58 | 42 | 36.5 | 93 | ≤0.0001 |

| Mut RNA Left | 88 | 12 | 12 | 50 | NS/≤0.0001 |

Mouse APOBEC2 inhibits TGFβ signaling and is necessary for proper differentiation of the myoblastic cell line C2C12

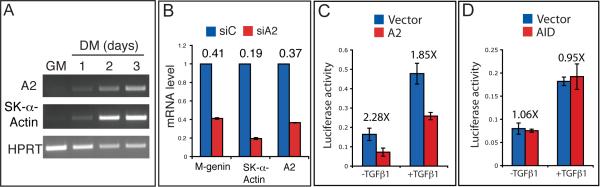

We next asked if the TGFβ inhibitory activity of APOBEC2 was conserved in mammals by testing its activity in the myoblastic C2C12 cell line. These cells can differentiate into myotube when shifted from high to low serum (McMahon et al., 1994). Smad2-mediated TGFβ signaling, however, inhibits this differentiation, and conversely, blocking TGFβ signaling accelerates formation of myotubes (Joulia et al., 2003; Massague et al., 1986; Olson et al., 1986; Rios et al., 2001; Rios et al., 2002). Interestingly, we find that while mouse APOBEC2 (mA2) is not expressed in undifferentiated C2C12 cells, its expression is induced during myotube differentiation (Figure 5A). As this pattern of expression suggests a potential role for A2 during myogenesis, we analyzed the consequences of reducing mA2 expression levels during C2C12 differentiation. Cells transfected with a specific siRNA targeting mA2 (siA2, Figure 5B, Supplementary Figure 2E) decreased expression of early (Myogenin) and late (Skeletal-α-Actin) muscle differentiation markers indicating that mA2 is required for myogenesis.

Figure 5. mAPOBEC2 inhibits TGFβ signaling in C2C12 myoblasts.

A. RT-PCR analysis of mA2 and the muscle differentiation marker Skeletal-α-Actin mRNA levels during C2C12 differentiation. B. Real-time qPCR analysis of the mRNA levels of A2 and the indicated muscle markers in C2C12 cells transfected either with control (siC) or anti-A2 (siA2) siRNAs and differentiated for 2 days in DM. Numbers above the histogram bars indicate the relative decrease in mRNA levels. C, D. A2, but not AID, inhibits TGFβ signaling in C2C12 cells. Cells were transfected with the p3TP-lux reporter in combination with an empty vector (Vector) or an A2 (C) or AID (D) expressing vector. After transfection, cells were cultured with or without 5ng/ml recombinant TGF-β1 for 24 hours before harvesting for luciferase assay. Numbers above the histogram bars indicate the fold reduction in luciferase activity.

To address the role of mA2 in the process, plasmids encoding CMV-mA2 were co-transfected together with the TGFβ-responding plasmid p3TP-lux (Wrana et al., 1992), used as reporter for transcriptional activation in C2C12 cells. Consistent with our observations in Xenopus, mA2 inhibited TGFβ1-induced transcription of the p3TP-lux reporter in C2C12 cells (Figure 5C). Interestingly, mA2 also inhibited the endogenous levels of TGFβ signaling, suggesting a potential direct role in myoblast differentiation in vivo. The activity of mA2 was specific, as the closely related family member AID did not repress TGFβ-mediated induction in the same experimental conditions (Figure 5D). The TGFβ inhibitory activity of APOBEC2 thus seems to be conserved in mammals.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that expression of a putative RNA/DNA editing enzyme, APOBEC2, is regulated by TGFβ signaling, and in turn regulates the pathway by ligand-specific inhibition, generating a negative feedback loop. This work also assigns a previously unrecognized biological function for APOBEC2 in the context of axis determination during early embryogenesis. The contribution of APOBEC2 to the TGFβ pathway, its mechanism of action, and its role during left-right specification are all unexpected, and discussed below.

We show that APOBEC2 (A2) regulates TGFβ signaling. A2 is a member of the cytidine deaminase family of DNA/RNA editing enzymes that emerged at the beginning of vertebrate radiation (Conticello, 2008). These enzymes can mutate C to U in DNA or RNA (Conticello et al., 2007; Navaratnam and Sarwar, 2006; Smith, 2008). The other members of the family are APOBEC1, AID and APOBEC3s (with several variants in primates). AID and APOBEC2 are the only members conserved among chordates, while APOBEC1 and APOBEC3s are mammalian-specific (Conticello et al., 2007). APOBEC1 edits apolipoprotein B mRNA in a tissue specific manner by introducing a premature stop codon leading to a shorter protein. AID has been shown to edit the immunoglobulin locus directly on genomic DNA to generate antibody diversification. Different variants of APOBEC3 protein edit retroelements and retroviruses, such as HIV-1, to provide retroviral immunity. The fact that TGFβ signaling regulates expression of xA2 suggests that, just as in the context of immuno-diversification or retroviral editing, non-autonomous signals control editing activity in early embryogenesis. However, while editing functions described for previous members of the family affect cellular activities without changing their fate, A2 affects cell fate decisions with implications in axis development. Selective inhibition of Derrière, but not Xnr1, by A2 also provides a hint to how signaling by similar TGFβ ligands using the same receptor complex and signal transducers (Smad2 and 3 for nodal and derrière) can be segregated by autonomous factors. A2 provides a negative feedback loop only for derrière, but not for Xnr1, presumably when presented as homodimers. The fate of signaling by heterodimers of the two ligands has not been addressed by this study.

Interestingly, it was recently shown that mA2 is required for normal muscle development. mA2-deficient mice exhibit slightly reduced muscle mass, increased slow:fast fiber ratio, and developed myopathy at 8-10 months of age (Sato et al., 2009). We show here that A2 is required for terminal differentiation of C2C12 myoblasts in vitro and that it can inhibit TGFβ signaling. It is tempting to speculate that the defects observed in vivo in mutant mice might be mediated by increased TGFβ signaling due to GDF-type ligands expressed in muscle cells, such as Myostatin/GDF8 and GDF11 (Artaza et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2005), in a A2-deficient background. This is also supported by the decrease in slow:fast fiber ratio seen in myostatin-deficient mice (Amthor et al., 2007; Girgenrath et al., 2005), indicating that APOBEC2 and myostatin have opposite effects on muscle in vivo.

Regarding the mechanism of the A2 effect in the context of left-right specification, it can act either as a DNA/RNA editing enzyme or by an independent, currently unknown, mechanism. While our experiments do not address this directly, the fact that conserved amino acids in the enzymatic domain required for the function of well established cytidine deaminases are also required for A2 biological activity suggests that A2 could at an editing level. Alternatively, A2 could, directly or indirectly, affect the translation or stability of proteins involved in TGFβ signaling.

If A2 acts as an editing enzyme, does it edit DNA, RNA, or both? The answer to this question is currently unknown. At the genomic level, APOBEC2 has been suggested to provide global changes in the methylation state of DNA in zebrafish embryos (Rai et al., 2008). While our study does not address this directly, a number of observations suggest that amphibian A2 is not involved in global changes of genomic DNA. First, the ligand-specific nature of the TGFβ inhibitory effect, directed at Derrière but not nodal, is not consistent with global methylation changes. Second, we note that overexpression of zAPOBEC2a (one of the two variants in the fish), unlike zAID and zAPOBEC2b, had no effect on genomic demethylation (Rai et al., 2008). This also suggests that the amphibian A2 is more similar to APOBEC2a, rather than the APOBEC2b ortholog in the fish. Finally, while in the fish both AID and APOBEC2 have been implicated in demethylation, we find that only A2 and not AID displays inhibitory activity in C2C12 cells, thus arguing against demethylation being causal to the activity.

We show that A2 activity is necessary for the specification of the left-right axis downstream of signaling. In agreement with this role, xA2 expression overlaps that of derrière in cells of the posterior mesoderm. Evidence for the appropriate timing of A2 activity in the context of left-right specification is provided by our rescue experiments where the laterality defects generated by xA2 depletion were rescued by induction of Smad2 activity at early neurula stages. This is the same developmental stage when the posterior mesoderm acts as a signaling center to pattern the left lateral late mesoderm, through Derrière and Xnr1 signaling. We therefore propose that selective inhibition of Derrière signaling in posterior mesoderm by APOBEC2 is required for the process underlying specification of laterality in the left lateral plate mesoderm. While this explains why A2 is necessary for proper left-right axis specification, and links the phenotypic outcome to molecular events, it also raises interesting questions. First, neither MO-mediated reduction of A2 function in zebrafish (Rai et al., 2008), nor knockout of APOBEC2 function by insertional disruption in the mouse (Mikl et al., 2005) have been reported to affect laterality. In the mouse, as stated above, other cytidine deaminases, (for example APOBEC3s), are present, that can theoretically compensate redundantly for lack of APOBEC2. In the zebrafish study, depletion was achieved with the same morpholino oligonucleotide as the one used in our work, and a possible explanation would be that a discreet phenotype like heart orientation could have escaped observation. Second, the mechanism of the selective effect of A2 on Derrière/GDF, as opposed to nodal signaling, remains unexplained. It remains to be seen if other differences reported on the molecular pathways activated by Nodal versus Derrière (Dorey and Hill, 2006; Howell et al., 2002) are connected to the role of A2.

Regardless of the outcome, A2, and perhaps other members of the DNA/RNA editing family of enzymes, provides yet another unexpected level of regulation for the TGFβ signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Embryo culture and injections

Xenopus embryos were fertilized in vitro and cultured in 0.1X MMR. For left-right axis experiments, embryos were injected, 10 nl per cell in the lateral subequatorial sector of dorsal blastomeres at the 4 cell stage for paraxial localization, or in the lateral subequatorial sector of ventral blastomeres for lateral plate mesoderm localization. These localizations correspond approximately to the 32 cell stage C2 and C3 blastomeres, which we have previously described to have paraxial and lateral plate localization (Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007). Coinjections of GFP RNA (1 ng, for phenotype) and LacZ RNA (1 ng, for double in situ hybridization staining) were used to select correctly injected embryos. Staging of embryos was done according to Nieuwkoop and Faber. For RT-PCR of posterior paraxial mesoderm, MO oligonucleotides were injected in both dorsal blastomeres and posterior dorsal fragments containing paraxial mesoderm were cut at stage 18 with a gastromaster (Xenotek Engineering). For RT-PCR and biochemistry of animal caps, all four blastomeres were injected in the animal pole, caps were cut at stage 9 and cultured in 0.5X MMR. For transcription assays, each ventral bastomere of 4 cell stage embryos was injected in the animal pole and embryos were collected at stage 11. For specific localization of different injection sites, 10 ng control fluorescent MO (GeneTools, LLC) was injected at 4 cell stage in the marginal lateral side of the left dorsal blastomere, and Cherry H2b RNA was injected in the marginal lateral side of the left ventral blastomere. Embryos were allowed to develop until stage 20, fixed in formaldehide and exposed to UV of the appropriate wavelength for imaging. Zebrafish embryos were injected at the 1 to 4 cell stage and reared at 28.5°C to appropriate developmental stages. Embryos were staged according to established morphological criteria (Kimmel et al., 1995).

Design of antisense morpholino oligonuceotides, siRNA and plasmid construction

Xenopus APOBEC2 (XA2) wild-type (CD327544, in pCMV-SPORT6 from ATCC) was used for in vitro translation and antisense probe transcription. For in vivo overexpression and rescue experiments we used CS2+XA2 FLAG, constructed as follows: XA2 open reading frame was amplified by PCR from the original vector with the oligonucleotides (S) 5’ CCG GAA TTC ACC ACC ATG GCg CAa cGa CAg AAc AAT TCA CAG TCT TCC AAG GAT 3’ where small case indicates conservative mutations in the MO-homology region, and (AS) 5’ CGG CTC TAG ATT ACT TGT CAT CGT CGT CCT TGT AGT CTC TTA GAA TCT CTG CCA GCT T 3’. The vector contains a C-terminal Flag tag. CS2+ MutXA2 was derived by mutagenizing E102 to Q (GAG to cAG), C130 to S (TGC to TcC) and C134 to S (TGT to TcT). CS2+XA2 HA was constructed by cloning the 5’ end of CS2+XA2 FLAG restricted with HinDIII into CS2+FLAG-PSP-XA2 HA construct.

Zebrafish APOBEC2 (zA2) (BC0907580, from Open Biosystems) was cloned into CS2+ as EcoRI/XbaI fragment from the original pDNR-LIB vector, and used to generate sense RNA for expression, and sense and antisense RNA probes.

The complete coding sequence of mouse APOBEC2 was PCR-amplified from C2C12 cDNA and cloned in the EcoRI site of the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen), giving rise to the CMV-Apobec2 plasmid.

MO oligonucleotides for XA2 and control fluorescent MO were obtained from Gene Tools, LLC. XA2 MO: 5’ GTG AAT TAT TTT GCC TCT GTG CCA T 3’; XA2 MO2: 5’ CTG TGC CAT TGT GAA TAA ACA GAG A 3’. The negative control siRNA (DS Scrambled Negative) and the siRNA targeting Apobec2 (NM_009694 duplex 2) were purchased from IDT. Derrière and Xnr1 MO have been described (Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007).

In vitro translation and RNA synthesis

Wild-type and 5' mutated xA2 RNA (1 μg) were in vitro translated and labeled with [S35]Met and rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega, Inc.) in the absence or presence of xA2 MO (10 μg, (Taylor et al., 1996). Wild-type zA2 RNA was similarly translated in vitro in the presence or absence of 10 μg zA2 MO or zA2 Mut MO. Translation reactions were run on 4-14% Invitrogen precast gels, dried and exposed to film. RNA synthesis was performed as previously described (Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007). RNAs for overexpression were in vitro transcribed from: CS2++CocoFLAG (Bell et al., 2003), CS2 Xnr1 and CS2 Xnr2 (from C. Wright), pSP64T Xnr4 (from D. Melton), pBS Xnr5 (from M. Asashima), pCS2+Vg1(Ser)HA (from J. Heasman), CS2++derrière (Cheng et al., 2003), CS2+GRVP16hSmad2Δ3 (Vonica and Brivanlou, 2007).

Xenopus transcription assays

For transcription assays, the nodal/activin specific reporter gene A3Luc (Liu et al., 1997) was coinjected with the inducible Smad2 construct GRVP16hSmad2Δ3 RNA in the animal pole at 4 cell stage. Embryos were cultured until stage 11, when they were processed for luciferase assays (Luciferase Assay System, Promega) as described (Vonica and Gumbiner, 2002). Results are expressed as arbitrary luciferase units. All assays were done in triplicate. Significance was calculated with Student's t test for unpaired data.

RT-PCR analysis (Xenopus) and Realtime PCR (cell culture)

Animal caps cultured in 0.5X MMR, posterior poles or whole embryos, were collected at the indicated stages and RNA was purified in batches of 10 and processed for semiquantitative RT-PCR as described (Wilson and Melton, 1994). Each experiment was repeated three times. For real-time RT-PCR analysis, RNA was treated with DNA-free kit (Ambion) to remove contaminant genomic DNA and reverse transcribed with the SuperScriptIII kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was then analyzed with LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I kit (Roche) in the LightCycler 480 machine (Roche) and results were analyzed with the REST software (Pfaffl et al., 2002). Sequences of oligonucleotides used are described in Supplementary Methods.

Cell culture, transfection and transcription assays

C2C12 myoblasts were maintained in high-glucose DMEM with 15% FBS growth medium (GM). For induction of differentiation, GM was replaced with differentiation medium (DM), containing 2% horse serum. Where indicated, cells were cultured in presence of 5ng/ml recombinant human TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Inc.) . siRNAs were transfected at a final 10nM concentration with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After six hours, the medium was changed to DM and the cells were analyzed after two days.

For luciferase assays, 300 ng of CMV-APOBEC2 plasmid were cotransfected in C2C12 cells along with 300 ng of the Firefly luciferase encoding plasmid p3TP-Lux and 30 ng of the Renilla luciferase-encoding plasmid pRL-TK (Promega, Inc.) in a 12-well plate. The day after, cells were analyzed for luciferase activity with the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Inc.), and results were expressed as the ratio of firefly vs. control renilla activity.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Whole mount in situ hybridization in Xenopus was as described (Harland, 1991), with full-length probes transcribed for the following vectors: pBS Xnr1 and pBS Xlefty-a (Branford et al., 2000), CS2++ Coco (Bell et al., 2003), pCMV-SPORT6 derrière (CA789921, from ATCC), pBS MyoD (from A. Salic, Harvard Med. Sch.). For double in situ hybridization, the marker was digoxigenin-labeled and stained with BMPurple (Roche), and the LacZ probe from the pSP6nucβGal (from R. Harland, Berkeley U.) was FITC-labeled and stained with Fast Red (Roche). All in situs were performed in a BioLane HT1 in situ robot (Holle & Huttner AG). The CS2+ Cherry H2b construct was a kind gift from A. Warmflash.

Zebrafish embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. In situ hybridizations were performed essentially as previously described (Thisse et al., 1993). Zcmlc2 construct was obtained from P.D. Henion (Yelon et al., 1999). ZA2 sense and antisense probes were generated from CS2+ ZA2 (see above).

Imaging was done with a Zeiss HBO 100 microscope and AxioVision imaging program and minimally enhanced in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 imaging program.

For immunohistochemistry of heart muscle, stage 46 Xenopus embryos were fixed in 4% PFA and incubated with MF20 monoclonal antibody for light meromyosin (1:20, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa) and stained with immunoperoxidase as described (Chen and Fishman, 1996).

Western blot

Samples were run on Invitrogen 4-12% or 10% precast gels, using LDS sample buffer. For Smad 2 phosphorylation, ten animal caps from control or injected embryos were lysed in 1% NP40 buffer. The blots were blocked with 1% serum and 5% milk, and incubated with 1:2500 anti-total Smad2/3 (rabbit polyclonal), 1:500 anti-Phospho C-terminal Samd2/3 (rabbit monoclonal), both from Cell Signaling. The FLAG tag was visualized with the rabbit anti-FLAG (1:5000, Sigma).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Drs. Ann C. Foley, Nina Papavasiliou, and Harold C. Smith for useful comments on the manuscript, Drs. G.T. Williams for the antibody against mouse A2 and K. McBride for the anti-AID antibody. We also thank Drs. M. Asashima, M. Blum, A. Salic, J. Heasman, P. D. Henion, D. Melton, C. Wright, A. Warmflash and H. J. Yost for plasmids. Blaine Cooper offered expert assistance for the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 HD032105 to A. H. B., R03 HD057334 to A. V., and A. R. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Human Frontier Science Program Organization.

References

- Amthor H, Macharia R, Navarrete R, Schuelke M, Brown SC, Otto A, Voit T, Muntoni F, Vrbova G, Partridge T, Zammit P, Bunger L, Patel K. Lack of myostatin results in excessive muscle growth but impaired force generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1835–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604893104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anant S, Mukhopadhyay D, Sankaranand V, Kennedy S, Henderson JO, Davidson NO. ARCD-1, an apobec-1-related cytidine deaminase, exerts a dominant negative effect on C to U RNA editing. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1904–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artaza JN, Bhasin S, Mallidis C, Taylor W, Ma K, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Endogenous expression and localization of myostatin and its relation to myosin heavy chain distribution in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:170–9. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E, Munoz-Sanjuan I, Altmann CR, Vonica A, Brivanlou AH. Cell fate specification and competence by Coco, a maternal BMP, TGFbeta and Wnt inhibitor. Development. 2003;130:1381–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgrove BW, Yost HJ. Classification of left-right patterning defects in zebrafish, mice, and humans. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2001;101:315–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgrove BW, Yost HJ. The roles of cilia in developmental disorders and disease. Development. 2006;133:4131–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.02595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand T. Heart development: molecular insights into cardiac specification and early morphogenesis. Developmental Biology. 2003;258:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branford WW, Essner JJ, Yost HJ. Regulation of gut and heart left-right asymmetry by context-dependent interactions between xenopus lefty and BMP4 signaling. Developmental Biology. 2000;223:291–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon M, Gomperts M, Sumoy L, Moon RT, Kimelman D. A beta-catenin/XTcf-3 complex binds to the siamois promoter to regulate dorsal axis specification in Xenopus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2359–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JN, Fishman MC. Zebrafish tinman homolog demarcates the heart field and initiates myocardial differentiation. Development. 1996;122:3809–16. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SK, Olale F, Bennett JT, Brivanlou AH, Schier AF. EGF-CFC proteins are essential coreceptors for the TGF-beta signals Vg1 and GDF1. Genes Dev. 2003;17:31–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1041203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conticello SG. The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol. 2008;9:229. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conticello SG, Langlois MA, Yang Z, Neuberger MS. DNA deamination in immunity: AID in the context of its APOBEC relatives. Adv Immunol. 2007;94:37–73. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)94002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale L. Development: morphogen gradients and mesodermal patterning. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R698–700. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorey K, Hill CS. A novel Cripto-related protein reveals an essential role for EGFCFCs in Nodal signalling in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 2006;292:303–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimon PM, Harland RM. Effects of heterodimerization and proteolytic processing on Derriere and Nodal activity: implications for mesoderm induction in Xenopus. Development. 2002;129:3089–103. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esguerra CV, Nelles L, Vermeire L, Ibrahimi A, Crawford AD, Derua R, Janssens E, Waelkens E, Carmeliet P, Collen D, Huylebroeck D. Ttrap is an essential modulator of Smad3-dependent Nodal signaling during zebrafish gastrulation and left-right axis determination. Development. 2007;134:4381–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essner JJ, Amack JD, Nyholm MK, Harris EB, Yost HJ. Kupffer's vesicle is a ciliated organ of asymmetry in the zebrafish embryo that initiates left-right development of the brain, heart and gut. Development. 2005;132:1247–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essner JJ, Vogan KJ, Wagner MK, Tabin CJ, Yost HJ, Brueckner M. Conserved function for embryonic nodal cilia.[see comment]. Nature. 2002;418:37–8. doi: 10.1038/418037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgenrath S, Song K, Whittemore LA. Loss of myostatin expression alters fiber-type distribution and expression of myosin heavy chain isoforms in slow- and fast-type skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:34–40. doi: 10.1002/mus.20175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. Morphogen gradients, positional information, and Xenopus: interplay of theory and experiment. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:392–408. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritsman K, Zhang J, Cheng S, Heckscher E, Talbot WS, Schier AF. The EGF-CFC protein one-eyed pinhead is essential for nodal signaling. Cell. 1999;97:121–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros J, Feistel K, Viebahn C, Blum M, Tabin CJ. Cell movements at Hensen's node establish left/right asymmetric gene expression in the chick. Science. 2009;324:941–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1172478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland R, Gerhart J. Formation and function of Spemann's organizer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:611–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland RM. In situ hybridization: an improved whole-mount method for Xenopus embryos. Methods in Cell Biology. 1991;36:685–95. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Rebagliati M, Ahmad N, Muraoka O, Kurokawa T, Hibi M, Suzuki T. The Cerberus/Dan-family protein Charon is a negative regulator of Nodal signaling during left-right patterning in zebrafish. Development. 2004;131:1741–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.01070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Takeda S. Nodal flow and the generation of left-right asymmetry. Cell. 2006;125:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell M, Inman GJ, Hill CS. A novel Xenopus Smad-interacting forkhead transcription factor (XFast-3) cooperates with XFast-1 in regulating gastrulation movements. Development. 2002;129:2823–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.12.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joulia D, Bernardi H, Garandel V, Rabenoelina F, Vernus B, Cabello G. Mechanisms involved in the inhibition of myoblast proliferation and differentiation by myostatin. Exp Cell Res. 2003;286:263–75. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Anderson KV. Morphogenesis of the node and notochord: The cellular basis for the establishment and maintenance of left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Dev Dyn. 2008 doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Reed LA, Davies MV, Girgenrath S, Goad ME, Tomkinson KN, Wright JF, Barker C, Ehrmantraut G, Holmstrom J, Trowell B, Gertz B, Jiang MS, Sebald SM, Matzuk M, Li E, Liang LF, Quattlebaum E, Stotish RL, Wolfman NM. Regulation of muscle growth by multiple ligands signaling through activin type II receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18117–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505996102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M. Left-right asymmetry in embryonic development: a comprehensive review. Mechanisms of Development. 2005;122:3–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Hong SH, Chan BH, Rudolph FB, Clark SC, Chan L. APOBEC-2, a cardiac- and skeletal muscle-specific member of the cytidine deaminase supergene family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:398–404. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Pouponnot C, Massague J. Dual role of the Smad4/DPC4 tumor suppressor in TGFbeta-inducible transcriptional complexes. Genes & Development. 1997;11:3157–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques S, Borges AC, Silva AC, Freitas S, Cordenonsi M, Belo JA. The activity of the Nodal antagonist Cerl-2 in the mouse node is required for correct L/R body axis. Genes & Development. 2004;18:2342–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.306504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J, Cheifetz S, Endo T, Nadal-Ginard B. Type beta transforming growth factor is an inhibitor of myogenic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:8206–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon DK, Anderson PA, Nassar R, Bunting JB, Saba Z, Oakeley AE, Malouf NN. C2C12 cells: biophysical, biochemical, and immunocytochemical properties. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C1795–802. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercola M. Left-right asymmetry: nodal points. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3251–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikl MC, Watt IN, Lu M, Reik W, Davies SL, Neuberger MS, Rada C. Mice deficient in APOBEC2 and APOBEC3. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7270–7. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7270-7277.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnam N, Sarwar R. An overview of cytidine deaminases. Int J Hematol. 2006;83:195–200. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi Y, Wright CV. Anteriorward shifting of asymmetric Xnr1 expression and contralateral communication in left-right specification in Xenopus. Dev Biol. 2007;301:447–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EN, Sternberg E, Hu JS, Spizz G, Wilcox C. Regulation of myogenic differentiation by type beta transforming growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1799–805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.5.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onuma Y, Yeo C-Y, Whitman M. XCR2, one of three Xenopus EGF-CFC genes, has a distinct role in the regulation of left-right patterning. Development. 2005;133:237–250. doi: 10.1242/dev.02188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce JJ, Penny G, Rossant J. A mouse cerberus/Dan-related gene family. Developmental Biology. 1999;209:98–110. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW, Georgieva TM, Georgiev IP, Ontsouka E, Hageleit M, Blum JW. Real-time RT-PCR quantification of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, IGF-1 receptor, IGF-2, IGF-2 receptor, insulin receptor, growth hormone receptor, IGF-binding proteins 1, 2 and 3 in the bovine species. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2002;22:91–102. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(01)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai K, Huggins IJ, James SR, Karpf AR, Jones DA, Cairns BR. DNA demethylation in zebrafish involves the coupling of a deaminase, a glycosylase, and gadd45. Cell. 2008;135:1201–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raya A, Belmonte JC. Left-right asymmetry in the vertebrate embryo: from early information to higher-level integration. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:283–93. doi: 10.1038/nrg1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios R, Carneiro I, Arce VM, Devesa J. Myostatin regulates cell survival during C2C12 myogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:561–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios R, Carneiro I, Arce VM, Devesa J. Myostatin is an inhibitor of myogenic differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C993–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00372.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Probst HC, Tatsumi R, Ikeuchi Y, Neuberger MS, Rada C. Deficiency in APOBEC2 leads to a shift in muscle fiber-type, diminished body mass and myopathy. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.052977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier AF, Talbot WS. Molecular genetics of axis formation in zebrafish. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:561–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweickert A, Weber T, Beyer T, Vick P, Bogusch S, Feistel K, Blum M. Cilia-driven leftward flow determines laterality in Xenopus. Curr Biol. 2007;17:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiratori H, Hamada H. The left-right axis in the mouse: from origin to morphology. Development. 2006;133:2095–2104. doi: 10.1242/dev.02384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook DR, Majer C, Keller R. Pattern and morphogenesis of presumptive superficial mesoderm in two closely related species, Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis. Dev Biol. 2004;270:163–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HC. RNA and DNA editing: molecular mechanisms and their integration into biological systems. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, N.J.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC. Mesoderm-inducing factors and mesodermal patterning. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:856–61. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Price BM, Green JB, Weigel D, Herrmann BG. Expression of a Xenopus homolog of Brachyury (T) is an immediate-early response to mesoderm induction. Cell. 1991;67:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90573-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speder P, Petzoldt A, Suzanne M, Noselli S. Strategies to establish left/right asymmetry in vertebrates and invertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:351–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BI, Bush SM, Collins-Racie LA, LaVallie ER, DiBlasio-Smith EA, Wolfman NM, McCoy JM, Sive HL. derriere: a TGF-beta family member required for posterior development in Xenopus. Development. 1999;126:1467–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.7.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka C, Sakuma R, Nakamura T, Hamada H, Saijoh Y. Long-range action of Nodal requires interaction with GDF1. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3272–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.1623907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MF, Paulauskis JD, Weller DD, Kobzik L. In vitro efficacy of morpholino-modified antisense oligomers directed against tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:17445–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B, Heyer V, Lux A, Alunni V, Degrave A, Seiliez I, Kirchner J, Parkhill JP, Thisse C. Spatial and temporal expression of the zebrafish genome by large-scale in situ hybridization screening. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;77:505–19. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)77027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B, Schilling TF, Postlethwait JH. Structure of the zebrafish snail1 gene and its expression in wild-type, spadetail and no tail mutant embryos. Development. 1993;119:1203–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonica A, Brivanlou AH. The left-right axis is regulated by the interplay of Coco, Xnr1 and derriere in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol. 2007;303:281–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonica A, Gumbiner BM. Zygotic Wnt activity is required for Brachyury expression in the early Xenopus laevis embryo. Developmental Biology. 2002;250:112–27. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman M. Nodal signaling in early vertebrate embryos: themes and variations. Dev Cell. 2001;1:605–17. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Melton DA. Mesodermal patterning by an inducer gradient depends on secondary cell-cell communication. Current Biology. 1994;4:676–86. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrana JL, Attisano L, Carcamo J, Zentella A, Doody J, Laiho M, Wang XF, Massague J. TGF beta signals through a heteromeric protein kinase receptor complex. Cell. 1992;71:1003–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90395-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CV. Mechanisms of left-right asymmetry: what's right and what's left? Developmental Cell. 2001;1:179–86. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YT, Liu JJ, Luo Y, E C, Haltiwanger RS, Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. Dual roles of Cripto as a ligand and coreceptor in the nodal signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4439–49. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4439-4449.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yelon D, Horne SA, Stainier DY. Restricted expression of cardiac myosin genes reveals regulated aspects of heart tube assembly in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 1999;214:23–37. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo C, Whitman M. Nodal signals to Smads through Cripto-dependent and Cripto-independent mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2001;7:949–57. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.