Abstract

Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) ligands are known to regulate virgin mammary development and contribute to initiation of post-lactation involution. However, the role for TGF-β during the second phase of mammary involution has not been addressed. Previously, we have used an MMTV-Cre transgene to delete exon 2 from the Tgfbr2 gene in mammary epithelium, however we observed a gradual loss of TβRII deficient epithelial cells that precluded an accurate study of the role for TGF-β signaling during involution timepoints. Therefore, in order to determine the role for TGF-β during the second phase of mammary involution we have now targeted TβRII ablation within mammary epithelium using the WAP-Cre transgene [TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R]. Our results demonstrated that TGF-β regulates commitment to cell death during the second phase of mammary involution. Importantly, at day 3 of mammary involution the Na–Pi type IIb co-transporter (Npt2b), a selective marker for active lactation in luminal lobular alveolar epithelium, was completely silenced in the WAP-Cre control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues. However, by day 7 of involution the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues had distended lobular alveoli and regained a robust Npt2b signal that was detected at the apical luminal surface. The Npt2b abundance and localization positively correlated with elevated WAP mRNA expression, suggesting that the distended alveoli were the result of an active lactation program rather than residual milk protein and lipid accumulation. In summary, the results suggest that an epithelial cell response to TGF-β signaling regulates commitment to cell death and suppression of lactation during the second phase of mammary involution.

Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-β) Ligand Expression During Mammary Development

The TGF-β pathway is known to significantly regulate mammary development and tumorigenesis. During mammary development, the TGF-β isoforms TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3 are expressed in distinct spatial and temporal patterns (Robinson et al., 1991, 1993; Streuli et al., 1993). It has been shown that all three isoforms are present during virgin mammary development and pregnancy. TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 levels were shown to be more abundant than TGF-β2 during virgin development and associated predominantly with the terminal end bud and ductal structures. However, TGF-β1 and TGF-β3 were also expressed in the mammary fat pad in the absence of epithelium. During pregnancy all three isoforms were abundantly expressed in mammary alveoli, ducts and fat pad. Upon parturition, all three TGF-β isoforms were significantly downregulated and only TGF-β3 was detected at low levels in mammary alveoli (Robinson et al., 1991). During involution, TGF-β3 expression was markedly upregulated through a process regulated by milk stasis and has been shown to be more abundant than TGF-β1 or TGF-β2 (Streuli et al., 1993; Nguyen and Pollard, 2000; Clarkson et al., 2004; Stein et al., 2004).

Functional Roles for TGF-β Signaling During Mammary Development

Relevance for TGF-β signaling during mammary development was shown in early studies using ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer (EVAc) pellets containing TGF-β that were implanted in the mammary fat pad of 5 weeks old virgin mice (Silberstein and Daniel, 1987). The TGF-β implants were able to inhibit the growth of terminal end buds (TEBs) into the fat pad, thereby preventing ductal elongation. It was further shown that the effect of growth inhibition by TGF-β was reversible. The effect of TGF-β signaling was specific to the epithelium and had no observed effect on the proliferation of adjacent stroma (Daniel et al., 1989). It was later shown that TGF-β1 +/− mammary epithelium, which produced ~10% of the TGF-β1 present in wild-type tissue, exhibited increased mammary lobuloalveolar proliferation in vivo (Geiser et al., 1993; Kulkarni et al., 1993; Ewan et al., 2002). Further, TGF-β could restrain hormone dependent mammary epithelial cell proliferation (Ewan et al., 2002). These results correlated well with data obtained through expression of a dominant negative type II TGF-β receptor mutant under control of the MMTV promoter/enhancer (MMTV-DNIIR) (Gorska et al., 1998). Attenuation of TGF-β signaling using this strategy resulted in mammary alveolar hyperplasia and precocious terminal differentiation (Gorska et al., 1998). Further, at 20 weeks of age the hyperplasia positively correlated with diestrus and estrus stages of development (Gorska et al., 1998). During pregnancy, the MMTV-DNIIR mice also exhibited an increased rate of precocious differentiation (Gorska et al., 2003), further linking the TGF-β pathway to regulation of the mammary epithelial cell response to endocrine signaling in vivo.

TGF-β3 signaling has been associated with regulation of the first stage of mammary involution (Nguyen and Pollard, 2000). To determine the effect of TGF-β3 signaling during mammary development an initial approach involved the use of transplanted glands derived from TGF-β3 null mice that have been shown to die shortly after birth (Proetzel et al., 1995; Nguyen and Pollard, 2000). The transplants indicated that the apoptotic effect involved autocrine signaling during mammary involution. Further, transgenic overexpression of TGF-β3 under control of the Blg promoter resulted in increased signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) phosphorylation and positively correlated with increased cell death in the first 3 days of post-partum transgene expression (Nguyen and Pollard, 2000). Subsequently, the MMTV-DNIIR mouse model was used to demonstrate a similar delay in mammary involution upon forced weaning of pups during lactation (Gorska et al., 2003). In addition mammary epithelial cell specific loss of Smad3, a well characterized downstream mediator of TGF-β signaling, was shown to have a similar effect on apoptotic induction during the first 3 days of involution (Yang et al., 2002). Interestingly deletion of Smad4, a central mediator and Smad3 binding partner that regulates canonical TGF-β signaling, in mammary epithelium did not reveal a corresponding involution defect (Li et al., 2003).

Regulation of Akt by TGF-β Opposes Prolactin Dependent Cell Survival During the First Stage of Mammary Involution

TGF-β and Prolactin (Prl) exert opposing effects on mammary epithelial cell survival (Bailey et al., 2004). It has been shown that in the relatively normal HC11 murine mammary epithelial cell line, TGF-β1 inhibits Akt phosphorylation at S473. Conversely, Prl activates Akt S473 phosphorylation and is dominant over the effect of TGF-β in the activation of this pathway. It was shown that TGF-β mediated apoptosis in this model system was dependent upon downregulation of Akt signaling. Conversely, Prl promoted cell survival through upregulation of Akt signaling. It was further shown, that the hyperplastic growth of mammary epithelium observed in MMTV-DNIIR mice was dependent upon Prl signaling in vivo through transplantation studies using MMTV-DNIIR mammary epithelium grown in a Prl(−/−) host (Bailey et al., 2004). These results were correlated with reduced apoptosis in the MMTV-DNIIR mouse model after nipple sealing experiments designed to induce localized involution of mammary tissue in vivo (Bailey et al., 2004).

TGF-β Signaling Promotes Cell Death and Suppresses Lactation During the Second Stage of Mammary Involution

The literature has suggested that TGF-β signaling could regulate initiation of early mammary involution (Proetzel et al., 1995; Nguyen and Pollard, 2000; Yang et al., 2002; Gorska et al., 2003; Bailey et al., 2004). Several reports have also suggested that TGF-β signaling was able to suppress terminal differentiation of mammary epithelium (Gorska et al., 1998, 2003; Cocolakis et al., 2008). However, it was unclear what impact either effect had on the global process of mammary involution. Previously, we have used an MMTV-Cre transgene to delete exon 2 from the Tgfbr2 gene in mammary epithelium, however we observed a gradual loss of TβRII deficient epithelial cells that precluded an accurate study of the role for TGF-β signaling during involution timepoints (Chytil et al., 2002; Forrester et al., 2005). To address this issue, using the WAP-Cre transgene and our floxed TβRII mouse model (Wagner et al., 1997; Chytil et al., 2002), we have now selectively ablated TβRII signaling in mammary epithelium predominantly associated with late pregnancy, lactation and early involution timepoints. Using this strategy, we have been able to determine that many of the processes that should occur during the first-to-second phase transition of mammary involution are not significantly altered in the absence of TGF-β signaling. Notably, we were able to detect the silencing of Na–Pi type IIb co-transporter (Npt2b) by day 3 of involution in both control and TβRII deleted tissues. In addition, we did not detect a significant difference in the level of apoptosis at day 3 of involution. However, by day 7 of involution Npt2b, a previously described Jak/Stat dependent terminal differentiation marker (Miyoshi et al., 2001; Long et al., 2003; Shillingford et al., 2003), was detected in TβRII deficient tissues. Together, the results suggest that induction of the second irreversible stage of mammary involution is not significantly altered when TGF-β signaling is completely abrogated. However, during the second stage of mammary involution TGF-β signaling promotes commitment to cell death and suppresses lactation in vivo.

Methods and Reagents

Animal models

WAP-Cre, TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R, TβRII(MKO), and MMTV-DNIIR mice were bred and genotyped as previously described (Wagner et al., 1997; Gorska et al., 1998, 2003; Soriano, 1999; Forrester et al., 2005; Bierie et al., 2008). WAP-Cre and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R mice were maintained on a C57Bl/6 and 129 background. Background strains for the TβRII(MKO) and DNIIR mice have been previously described (Gorska et al., 1998; Forrester et al., 2005). Virgin timepoints for the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R and WAP-Cre control analyses included 12 and 20 weeks of age. Four TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R and six WAP-Cre mice were used for each genotype at the virgin timepoints. Virgin tissues from the TβRII(MKO) model were collected at 19 weeks of age and the virgin MMTV-DNIIR tissues were collected at 20 weeks of age [mouse models and tissue collection have been previously described (Gorska et al., 1998; Forrester et al., 2005)]. Mice were checked for plugs after breeding to determine the first day of pregnancy for the day 15 pregnancy timepoint. Four mice were used for each genotype at day 15 of pregnancy. Day 3 of lactation was used for the corresponding lactation timepoint with five mice in the control group and four mice in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R group. Forced involution was conducted by allowing pups to suckle for 10 days after parturition, then removing the pups. Six WAP-Cre and five TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R mice were collected at day 1 after forced involution. Eight WAP-Cre and six TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R mice were collected at day 2 after forced involution. Seven WAP-Cre and nine TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R mice were collected at day 3 after forced involution. Ten WAP-Cre and ten TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R mice were collected at day 6 after forced involution. Eight WAP-Cre and nine TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R mice were collected at day 10 after forced involution. Animals were handled according to approved Vanderbilt Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols.

Histology, immunofluorescence (IF), and TUNEL analyses

Paraffin embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μM for both hematoxylin and esosin stained sections and unstained sections used for immunofluorescence (IF) and TUNEL analyses. Npt2b IF was conducted using a custom polyclonal rabbit C-terminal antibody (1:2,000, 2 h at room temperature) kindly provided by Dr. Fayez Ghishan at the University of Arizona Steele Children’s Research Center. Sodium citrate (pH 6) was used for antigen retrieval. The secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit alexa 594 from Invitrogen (A11012). Apoptag TUNEL analyses were conducted as previously described (Bierie et al., 2008). Quantitation of relative TUNEL positive cell counts was determined using three random fields of lobular alveolar structures for each tissue section and three sections from individual mice for each genotype and timepoint. P-values were determined using un-paired t-tests.

Western and Northern blot analyses

Tissues were snap frozen and kept at −80°C until protein or RNA were prepared for analysis. Protein was prepared and Western blots were run as previously described (Bierie et al., 2008). Primary antibodies including Stat3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA #9132, 1:1000), p-Stat3 Tyr-705 (Cell Signaling #9131, 1:1,000), p53 (Novacastra Laboratories, Newcastle, UK #NCL-p53-CM5p, 1:500) and β-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO #A-2066, 1:5,000) were incubated at 4°C overnight. The HRP conjugated secondary antibody was visualized using Amersham ECL, GE Healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK) (Stat3 and β-actin) or ECL plus (p-Stat3 and p53) reagent from Amersham ECL, GE Healthcare (UK). RNA was prepared using a standard guanidinium thiocyanate phenol chloroform extraction (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). Northern blots were performed as previously described (Gorska et al., 1998, 2003). WAP, p53, and CypA probes have been previously reported (Gorska et al., 1998, 2003; Thangaraju et al., 2005). The p53 probe was kindly provided by Dr. Esta Sterneck, Laboratory of Cell and Developmental Signaling, NCI at NIH.

Results

WAP-Cre mediated epithelial cell specific deletion of TβRII resulted in accumulation of milk protein and lipid products during mammary involution

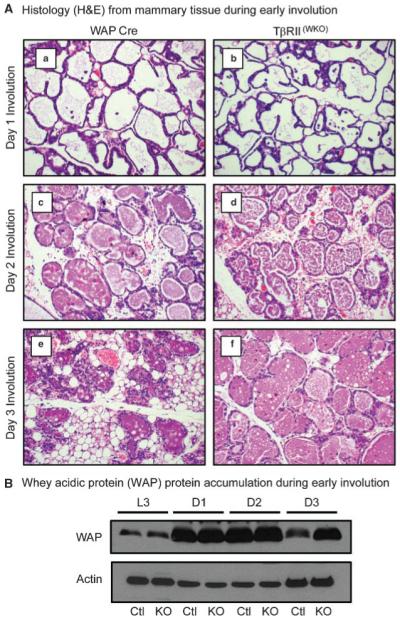

We deleted exon 2 from the Tgfbr2 gene in mammary epithelial cell populations using the WAP-Cre transgene and examined tissues derived from virgin, pregnancy, lactation and involution timepoints. The Rosa26R reporter was used to determine the efficiency of WAP-Cre mediated recombination (Supplemental Fig. S1). The results for Rosa26R activation in our WAP-Cre targeted type II TGF-β receptor (TβRII) deficient model [TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R] closely paralleled the previously reported expression profile for the WAP-Cre transgene in vivo (Wagner et al., 1997). Deletion was only detected in lobular alveolar epithelium. During virgin mammary development we collected tissues at 12 and 20 weeks of age. The virgin timepoints were included due to recent reports that WAP-Cre can mediate recombination in a small subset of virgin mammary progenitor cells during development with a slight increase in the number of cells targeted during estrus (Kordon et al., 1995). However, we did not observe a phenotype in the virgin tissues at either timepoint related to lobular alveolar hyperplasia or precocious terminal differentiation upon analysis of whole mount staining and histological sections. We examined tissues at day 15 of pregnancy and day 3 of lactation when WAP-Cre is known to be induced. We did not observe a significant difference in the mammary tissues by whole mount staining and histological analyses at either timepoint. In opposition to previous reports of increased precocious differentiation and lactation in mammary epithelium with attenuated TGF-β signaling, our analysis of WAP gene expression by Northern blot did not reveal a statistically significant difference between the control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R models during virgin or pregnancy timepoints (Supplemental Fig. S2). We next examined days 1, 2, 3, 7, and 10 of involution. We did not observe any differences in morphology at day 1 or 2 of involution; however, at day 3 of involution many of the alveoli in the control tissues had collapsed whereas the alveoli in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues were predominantly distended (Fig. 1A,a–d). Further, we observed a clear difference in WAP protein abundance by day 3 of involution (Fig. 1B). At this timepoint WAP protein was more abundant in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues when compared with those in the WAP-Cre control model. WAP mRNA expression was not significantly altered in the absence of TGF-β signaling suggesting that the WAP protein abundance was due to lack of clearance rather than maintenance of WAP gene expression (Supplemental Fig. S2). During later timepoints, at 7 and 10 days of involution, the alveoli present in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues appeared distended and demonstrated evidence of milk protein and lipid secretion from mammary epithelium in hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Together, these observations suggested that the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R were resistant to complete involution and the remaining alveoli were actively secreting milk protein and lipid products during late involution timepoints (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Histology and accumulation of whey acidic protein (WAP) during early involution. A: Histology from mammary tissues during involution. a,c,e: Control mammary tissues expressing only the WAP-Cre transgene at days 1 (a), 2 (c), and 3 (e) after forced involution. b,d,f: TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues at days 1 (b), 2 (d), and 3 (f) after forced involution. No differences were noted in histology associated with the first 2 days of involution. However, by the third day of involution control lobular alveolar structures began to collapse while many lobular alveolar structures in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues at the same time point remained distended. B: Western blot analysis of WAP protein abundance indicated an accumulation in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues when compared with the control tissues at the same timepoint. Ctl, WAP-Cre; KO, TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R; L3, lactation day 3; D1, involution day 1; D2, involution day 2; D3, involution day 3.

Fig. 2.

Histology during late stages of mammary involution and remodeling. A: Histology of mammary tissue associated with day 7 after forced involution. a,b: Control mammary tissues expressing only the WAP-Cre transgene. c,d: TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues. At low magnification (a,c) the control tissues appeared largely remodeled with minimal evidence of residual terminally differentiated lobular alveolar structures while TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues display an intermediate stage of partial remodeling with many residual expanded lobular alveoli. At higher magnification (b,d), the alveoli in control tissues appear to have returned to a virgin like state while the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues displayed the presence an eosin stained protein component in addition to abundant lipid droplets within the alveolar lumina. B: Histology of mammary tissue associated with day 10 after forced involution. a,b: Control mammary tissues expressing only the WAP-Cre transgene. c,d: TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues. The control tissue at this timepoint exhibited nearly complete remodeling at low (a) and high magnification (b). TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues at this timepoint remained in an intermediate state of partial involution and remodeling (c). At higher magnification distended alveoli were visible (d), however the expansion was not as prevalent at this timepoint when compared with tissues from day 7 of involution.

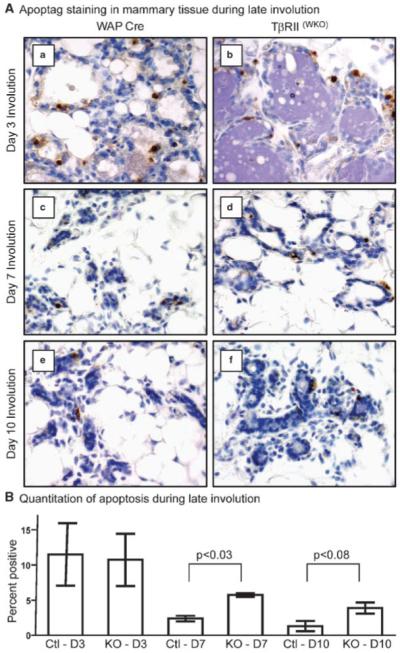

Loss of TβRII is associated with delayed cell death during the second stage of mammary involution

The difference in WAP protein abundance at day 3 of involution prompted apoptosis analyses starting at this timepoint, since it was known that the second irreversible stage of mammary involution correlates with the downregulation of milk gene expression. We performed TUNEL analyses on tissues from days 3, 7, and 10 of involution in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R and control mammary tissues (Fig. 3). At day 3 of involution we did not detect a difference in the level of cell death when comparing the two models. However, at days 7 and 10 of involution we detected a significant increase in the percentage of apoptotic epithelial cells associated with TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues when compared to the controls. This observation together with the gross histological analyses suggested that most of the apoptosis was complete in the control tissues by day 7 of involution and the process had been delayed upon deletion of TβRII in the mammary epithelium.

Fig. 3.

Apoptosis analysis at days 3, 7, and 10 of involution. A: Apoptag (TUNEL) IHC of mammary tissues during involution. a,c,e: Control mammary tissues expressing only the WAP-Cre transgene at days 3 (a), 7 (c), and 10 (e) after forced involution. b,d,f: TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues at days 3 (b), 7 (d), and 10 (f) after forced involution. B: Quantitation of percent Apoptag positive cells at days 3 (D3), 7 (D7), and 10 (D10) of involution. Three random apoptotic fields per section were counted with three individual mice per genotype at each timepoint. The increased apoptosis detected in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues likely reflects the delay of involution whereas this process is nearly complete in the WAP-Cre model by days 7 and 10 of involution.

To determine if major changes in known apoptotic signaling pathways could account for the apparent delay in apoptosis associated with the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues we performed a panel of Western and Northern blot analyses. Specifically, we performed Western blot analyses to determine the relative abundance of Stat3, p-Stat3, p42/44, p-p42/44, MEK1/2, p-MEK1/2, p38, p53, Bax, Bad, Bid, Bim, Bcl-xl, Bcl-2, GP130, C/EBP-delta, Dapk2, Puma, c-jun, jun-D, fos-B, c-fos and cleaved Caspase-3 proteins. Interestingly, the only consistent difference that corresponded to the changes observed during late involution timepoints occurred in the pro-apoptotic Stat3 and p53 pathways (Fig. 4). Activation of Stat3, which is known to promote apoptosis during mammary involution, was more abundant in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues when compared to the controls at day 3 of mammary involution. This correlated well with the accumulation of WAP protein in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues, since it is known that alveolar stretch from milk accumulation can increase Stat3 activation. However, the apoptosis results (Fig. 3) suggested that Stat3 activation in the absence of TGF-β signaling was not able to significantly enhance cell death during the second phase of mammary involution. No significant difference in Stat3 activation was detected by days 7 or 10 of involution. The abundance of p53 protein, which is known to be elevated during involution, was similar when comparing the control and TGF-β signaling deficient models at day 3 of involution. Interestingly, p53 mRNA expression was elevated at days 7 and 10 of involution despite protein abundance that was below the threshold of detection by Western blot at these timepoints. The elevated p53 message at days 7 and 10 of involution likely reflected a proportional difference in stromal–epithelial cell populations present at the late involution timepoints. Further, this interpretation correlated well with analysis of the histological sections that suggested involution was nearly complete in the control tissues by day 7 of involution whereas the process was significantly delayed in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R model.

Fig. 4.

Stat3 and p53 during late stages of mammary involution. A: At day 3 of involution, activated Stat3 (phosphorylation of Tyr-705) was more prevalent in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues. However, p53 protein abundance was not significantly elevated at this timepoint. Stat3α was more prevalent than Stat3β in both models at this timepoint. β-actin was used as a loading control. Ctl, WAP-Cre; KO, TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R. B: At 7 days of involution, Stat3 activation was comparable between the control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R models. Stat3β was observed in both models at this timepoint, however p53 protein abundance was below the threshold of detection by Western blot in both models. β-actin was used as a loading control. C: At day 10 after forced involution, Stat3 activation was significantly reduced in the control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R models with only one of the three TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R models exhibiting an elevated level of Stat3 activation at this timepoint. Stat3α and Stat3β levels were comparable in the control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R models. p53 protein abundance was below the threshold of detection by Western blot in both models. D: Although p53 protein abundance was below the threshold for Western blot detection, p53 mRNA expression analyses by Northern blot revealed an elevated level of expression in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues at days 7 and 10 of involution when compared with the WAP-Cre controls. CycA, cyclophillin A was used as a loading control. Ctl, WAP-Cre; KO, TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R.

Na–Pi type IIb co-transporter (Npt2b) IF silencing was not altered during the first phase of mammary involution when TβRII was ablated in mammary epithelium

The histological examination and differences in the rate of apoptosis, together with the Western and Northern blot analyses suggested that there may be a delay in committing to the second irreversible phase of involution associated with the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues. However, further analysis was necessary to refine the interpretation. Although we were able to show increased WAP protein accumulation in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R mammary tissues at day 3 of involution, the Western blot analyses alone did not indicate that the mammary tissues were actively producing lactation associated gene products. Further, Western blot analyses lacked the ability to demonstrate specifically which cells were actively secreting lactation products if present at each timepoint during involution. We felt that it was critical to understand if the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R glands were responding to any of the normal apoptotic stimuli present during involution, or alternatively, if they were completely resistant to the signals that correlate with induction of the second stage of mammary involution. A highly sensitive marker for active lactation, Npt2b, has been used previously as a correlate with lactation status in other systems (Miyoshi et al., 2001; Long et al., 2003; Shillingford et al., 2003). To address this issue, we performed IF for Npt2b to determine if there was a shift in the downregulation of this lactation marker during the process of involution in our tissues (Figs. 5 and 6). We analyzed day 3 of lactation as a positive control and involution timepoints including days 1, 2, and 3 after forced weaning. During lactation, no differences were observed in Npt2b IF intensity or localization (Fig. 5A). In the early involution timepoints, at day 1 through day 3 after forced weaning, there were no observed differences in Npt2b IF (Fig. 5B). Notably, at day 3 of involution, Npt2b was not expressed at the apical surface of either the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R or control tissues (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of Npt2b IF during lactation and early involution. A: IF analysis to determine abundance and localization of Npt2b during lactation. Npt2b was present at the apical surface of lobular alveoli whereas no IF signal was detected in association with ductal epithelium (a, arrow). During lactation, no significant differences were observed when comparing the WAP-Cre (a) and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues (b). B: IF analysis to determine abundance and localization of Npt2b during days 1 and 2 of involution. No significant difference in Npt2b localization or abundance were observed at either timepoint when comparing WAP-Cre and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues. In control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues no shift in Npt2b IF silencing was observed that would indicate a significant difference in the initiation of the second phase of mammary involution.

Fig. 6.

Presence of a lactogenic phenotype during late stages of mammary involution. A: Npt2b IF detection at day 10 after forced involution. a: WAP-Cre control tissues did not display a Npt2b IF signal, while TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues (b) had a robust Npt2b signal at the apical surface of luminal lobular alveolar epithelial cells. B: Whey acidic protein (WAP) mRNA expression during late involution. WAP expression was completely silenced in WAP-Cre control tissues by day 7 of involution, however it was expressed at a relatively high level in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues. CypA, cyclophillin A was used as a loading control. C: Localization of Npt2b in virgin TβRII(MKO) and MMTV-DNIIR tissues. Aberrant terminally differentiated lobular alveolar structures obtained from mice during virgin mammary development expressed Npt2b at the luminal apical epithelial surface in both alternate models of mammary epithelial cell specific TGF-β signaling deficiency.

Lactation associated Npt2b protein IF was increased in TβRII ablated mammary epithelium during late stages of involution

Our apoptosis and Npt2b results indicated that the glands lacking TβRII in mammary epithelium were in some ways able to respond to apoptotic stimuli through the first 3 days of involution. The silencing of Npt2b IF did not appear to be significantly altered throughout these timepoints in vivo. However, the histology associated with late involution timepoints suggested that the glands were actively producing milk protein and lipid products (Fig. 2A,B). Importantly, at days 7 and 10 of involution there was a clear difference between the models with regard to Npt2b IF (Fig. 6A). In the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues, the remaining distended lobular alveolar structures also demonstrated robust Npt2b IF signal at the apical luminal surface. The mammary alveolar epithelial cells that remained within the gland closely resembled aberrant lobular alveolar side-branches previously described as functionally regulated by TGF-β in vivo (Gorska et al., 1998, 2003; Chytil et al., 2002; Forrester et al., 2005).

To further validate the Npt2b results, and to examine the status of milk gene expression, we performed Northern blot analyses for WAP mRNA using control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissue during late involution timepoints (Fig. 6B). The results indicated that WAP gene expression was completely silenced in the control tissues by day 7 of involution, whereas the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues maintained expression at a relatively high level through day 10 of involution. These results were unexpected due to the complete silencing of Npt2b IF in both control and TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues at day 3 of involution (Supplemental Fig. S3). Together, the Npt2b data and WAP gene expression profile indicated that lactation was maintained in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues during late stages of mammary involution and remodeling.

Terminally differentiated mammary epithelium during late stage TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R involution resembled precocious terminal differentiation in alternate models of TGF-β signaling deficient mammary tissue

The localization of Npt2b expressing lobular alveolar structures in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues appeared morphologically similar to those observed in the previously described TβRII(MKO) and MMTV-DNIIR models. However, Npt2b IF was not previously performed in these models and therefore it was not possible to make a direct comparison. We probed the TβRII(MKO) and MMTV-DNIIR models for Npt2b using IF and found a striking similarity between our TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R late involution tissues and the aberrant lobular alveolar structures from mammary tissues in the two previously described mouse models (Fig. 6C). Together, the results suggested that the late involution phenotype observed in our TβRII model may actually represent both resistance to apoptosis and a deficiency in suppressing differentiation of mammary epithelium as previously described in the TβRII(MKO) and MMTV-DNIIR models. This compound influence is likely, since we have permanently deleted TβRII from the mammary lobular alveolar epithelium starting at mid-pregnancy. As a result, the TβRII deleted epithelial cells may no longer be able to respond to TGF-β dependent suppression of aberrant growth or spontaneous terminal differentiation during late involution and remodeling within the mammary microenvironment. The only substantial difference between our TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R model and the MMTV driven lines during late involution and remodeling is the epithelial cell subpopulation targeted by the promoter driving transgene expression in each model. In our WAP-Cre targeted TβRII ablation model, the phenotype should only arise from terminally differentiated lobular alveolar mammary epithelial cells or the previously described parity induced mammary epithelial cell (PiMEC) population (Wagner et al., 1997; Henry et al., 2004). In the MMTV-Cre mediated deletion of TβRII or MMTV-DNIIR models the phenotype may have arisen from the basal, ductal or lobular alveolar cell populations (Andrechek et al., 2000; Wagner et al., 2001).

Discussion

Our observations upon ablation of the TGF-β response within mammary epithelium suggested that TGF-β can regulate the duration of post-lactation milk accumulation and commitment to cell death during the second phase of mammary involution. In the case of TGF-β dependent regulation of milk protein genes, it has been previously shown that TGF-β dependent Smad signaling can inhibit β-casein production though competition with Stat5 for Creb binding protein (CBP) association at the β-casein gene promoter (Cocolakis et al., 2008). The interaction between Smad3 and Smad4 with CBP prevented Stat5 from co-activating transcription that is dependent upon functional Stat5/CBP complexes. It was also shown that hydrocortisone, insulin and prolactin treatment significantly blocked TGF-β dependent activation of the 3TP-luc reporter (Cocolakis et al., 2008). Together, these results suggest a mutually antagonistic relationship between the Jak/Stat and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways with regard to the regulation of transcription. Although this mechanism was clearly demonstrated using a promoter construct in vitro, the mechanism may be slightly different in the context of a three dimensional mammary microenvironment. In mammary explant cultures TGF-β signaling was also shown to suppress casein synthesis; however, the data indicated that TGF-β regulated casein secretion without having an effect on transcription (Robinson et al., 1993). In subsequent independent experiments, it was shown that TGF-β stimulation had an impact on the differentiation of mammary epithelial cells through preventing the acquisition of a lactogenic phenotype rather than directly inhibiting production or secretion of existing β-casein protein in mammary organ culture explants (Sudlow et al., 1994). In our studies, the data suggested an intermediate mechanism that does not entirely align with any of the previously described models. During the first 2 days of involution in our study, Npt2b IF demonstrated no difference in either mouse model and was completely silenced by day 3 of involution. However, in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues, a robust Npt2b signal was detected using IF by day 7 of forced involution. Whereas the literature has suggested that lactation may be maintained upon loss of TGF-β signaling, our results suggest that loss of TGF-β signaling can promote re-initiation of the Npt2b IF signal rather than prolonged maintenance of this marker in vivo.

In addition to increased sensitivity to stimuli that may result in a lactation phenotype, our results suggested that there were intrinsic differences that enhanced epithelial cell survival in the presence of elevated pro-apoptotic Stat3 activation at day 3 of involution. In mammary epithelial cells, previously published data has suggested that pro-apoptotic effectors may be activated when cells are stimulated with TGF-β1 (Mieth et al., 1990; Kolek et al., 2003). Using a combination of confocal microscopy and immunoelectron spectroscopy to determine the spatial distribution of pro-apoptotic proteins after TGF-β1 stimulation it was shown that Bax/Bid, caspase-8/Bax/Bid and Bax/VDAC-1 co-localized on the membranes of mitochondria (Kolek et al., 2003). The co-localization of these complexes on the mitochondrial membrane was suggested to represent activation. We had hypothesized that if present, some of the resistance to apoptosis may have been due to alteration of these well characterized apoptotic pathways. However, we were unable to detect changes in caspase-3 cleavage that would indicate an altered balance in the net pro- versus anti-apoptotic pathways in vivo.

In addition, no changes were observed in the abundance of GP130 or C/EBP-delta that are thought to be the main activator and effector proteins for the Stat3 signaling pathway during mammary involution respectively. Stat3 has been previously shown to be a dominant player in the initiation of the second irreversible stage of mammary involution (Chapman et al., 1999; Humphreys et al., 2002). Interestingly, our data suggested that Stat3 activation was elevated in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissues despite the lack of difference in apoptosis rates or C/EBP-delta elevation at day 3 of involution. In addition, p53 presence represents a pro-apoptotic signal that was elevated in the TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R tissue at days 7 and 10 of involution. This link is interesting in light of recent data, demonstrating that the p53 and TGF-β pathways may interact to regulate a number of processes in vivo (Cordenonsi et al., 2003, 2007; Dupont et al., 2004). However, it is likely that this result in our system simply reflects the delay of involution in TβRII(WKO)Rosa26R glands when compared with the control tissues that are largely remodeled at the days 7 and 10 involution timepoints. In summary, our data suggest that some of the early mammary involution processes are not entirely dependent upon TGF-β signaling. Further, our results suggest that an unknown TGF-β dependent mechanism is required for efficient commitment to apoptotic cell death and suppression of terminal differentiation that may occur during the second irreversible phase of mammary involution in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

HLM is supported by grants: CA085492-06, CA102162, and CA126505 and funding from the T.J. Martell Foundation.

Footnotes

BB, AG, and DS have nothing to declare.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Literature Cited

- Andrechek ER, Hardy WR, Siegel PM, Rudnicki MA, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Amplification of the neu/erbB-2 oncogene in a mouse model of mammary tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3444–3449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050408497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JP, Nieport KM, Herbst MP, Srivastava S, Serra RA, Horseman ND. Prolactin and transforming growth factor-beta signaling exert opposing effects on mammary gland morphogenesis, involution, and the Akt-forkhead pathway. Mol Endocrinol (Baltimore, MD) 2004;18:1171–1184. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierie B, Stover DG, Abel TW, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Aakre M, Forrester E, Yang L, Wagner KU, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor-beta regulates mammary carcinoma cell survival and interaction with the adjacent microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1809–1819. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RS, Lourenco PC, Tonner E, Flint DJ, Selbert S, Takeda K, Akira S, Clarke AR, Watson CJ. Suppression of epithelial apoptosis and delayed mammary gland involution in mice with a conditional knockout of Stat3. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2604–2616. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chytil A, Magnuson MA, Wright CV, Moses HL. Conditional inactivation of the TGF-beta type II receptor using Cre:Lox. Genesis. 2002;32:73–75. doi: 10.1002/gene.10046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson RW, Wayland MT, Lee J, Freeman T, Watson CJ. Gene expression profiling of mammary gland development reveals putative roles for death receptors and immune mediators in post-lactational regression. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R92–R109. doi: 10.1186/bcr754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocolakis E, Dai M, Drevet L, Ho J, Haines E, Ali S, Lebrun JJ. Smad signaling antagonizes STAT5-mediated gene transcription and mammary epithelial cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1293–1307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Maretto S, Insinga A, Imbriano C, Piccolo S. Links between tumor suppressors: p53 is required for TGF-beta gene responses by cooperating with Smads. Cell. 2003;113:301–314. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00308-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordenonsi M, Montagner M, Adorno M, Zacchigna L, Martello G, Mamidi A, Soligo S, Dupont S, Piccolo S. Integration of TGF-beta and Ras/MAPK signaling through p53 phosphorylation. Science. 2007;315:840–843. doi: 10.1126/science.1135961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel CW, Silberstein GB, Van Horn K, Strickland P, Robinson S. TGF-beta 1-induced inhibition of mouse mammary ductal growth: Developmental specificity and characterization. Dev Biol. 1989;135:20–30. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Zacchigna L, Adorno M, Soligo S, Volpin D, Piccolo S, Cordenonsi M. Convergence of p53 and TGF-beta signaling networks. Cancer Lett. 2004;213:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewan KB, Shyamala G, Ravani SA, Tang Y, Akhurst R, Wakefield L, Barcellos-Hoff MH. Latent transforming growth factor-beta activation in mammary gland: Regulation by ovarian hormones affects ductal and alveolar proliferation. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:2081–2093. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester E, Chytil A, Bierie B, Aakre M, Gorska AE, Sharif-Afshar AR, Muller WJ, Moses HL. Effect of conditional knockout of the type II TGF-beta receptor gene in mammary epithelia on mammary gland development and polyomavirus middle T antigen induced tumor formation and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2296–2302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser AG, Letterio JJ, Kulkarni AB, Karlsson S, Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-beta 1) controls expression of major histocompatibility genes in the postnatal mouse: Aberrant histocompatibility antigen expression in the pathogenesis of the TGF-beta 1 null mouse phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9944–9948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorska AE, Joseph H, Derynck R, Moses HL, Serra R. Dominant-negative interference of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor in mammary gland epithelium results in alveolar hyperplasia and differentiation in virgin mice. Cell Growth Differ. 1998;9:229–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorska AE, Jensen RA, Shyr Y, Aakre ME, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL. Transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor exhibit impaired mammary development and enhanced mammary tumor formation. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1539–1549. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63510-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry MD, Triplett AA, Oh KB, Smith GH, Wagner KU. Parity-induced mammary epithelial cells facilitate tumorigenesis in MMTV-neu transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2004;23:6980–6985. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys RC, Bierie B, Zhao L, Raz R, Levy D, Hennighausen L. Deletion of Stat3 blocks mammary gland involution and extends functional competence of the secretory epithelium in the absence of lactogenic stimuli. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3641–3650. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolek O, Gajkowska B, Godlewski MM, Tomasz M. Co-localization of apoptosis-regulating proteins in mouse mammary epithelial HC11 cells exposed to TGF-beta1. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82:303–312. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordon EC, McKnight RA, Jhappan C, Hennighausen L, Merlino G, Smith GH. Ectopic TGF beta 1 expression in the secretory mammary epithelium induces early senescence of the epithelial stem cell population. Dev Biol. 1995;168:47–61. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Ward JM, Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Qiao W, Chen L, Xu X, Yang X, Li D, Li C, Brodie SG, Meguid MM, Hennighausen L, Deng CX. Squamous cell carcinoma and mammary abscess formation through squamous metaplasia in Smad4/Dpc4 conditional knockout mice. Development (Cambridge, England) 2003;130:6143–6153. doi: 10.1242/dev.00820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long W, Wagner KU, Lloyd KC, Binart N, Shillingford JM, Hennighausen L, Jones FE. Impaired differentiation and lactational failure of Erbb4-deficient mammary glands identify ERBB4 as an obligate mediator of STAT5. Development (Cambridge, England) 2003;130:5257–5268. doi: 10.1242/dev.00715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieth M, Boehmer FD, Ball R, Groner B, Grosse R. Transforming growth factor-beta inhibits lactogenic hormone induction of beta-casein expression in HC11 mouse mammary epithelial cells. Growth Factors. 1990;4:9–15. doi: 10.3109/08977199009011005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Shillingford JM, Smith GH, Grimm SL, Wagner KU, Oka T, Rosen JM, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (Stat) 5 controls the proliferation and differentiation of mammary alveolar epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:531–542. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AV, Pollard JW. Transforming growth factor beta3 induces cell death during the first stage of mammary gland involution. Development (Cambridge, England) 2000;127:3107–3118. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proetzel G, Pawlowski SA, Wiles MV, Yin M, Boivin GP, Howles PN, Ding J, Ferguson MW, Doetschman T. Transforming growth factor-beta 3 is required for secondary palate fusion. Nat Genet. 1995;11:409–414. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SD, Silberstein GB, Roberts AB, Flanders KC, Daniel CW. Regulated expression and growth inhibitory effects of transforming growth factor-beta isoforms in mouse mammary gland development. Development (Cambridge, England) 1991;113:867–878. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.3.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SD, Roberts AB, Daniel CW. TGF beta suppresses casein synthesis in mouse mammary explants and may play a role in controlling milk levels during pregnancy. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:245–251. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingford JM, Miyoshi K, Robinson GW, Bierie B, Cao Y, Karin M, Hennighausen L. Proteotyping of mammary tissue from transgenic and gene knockout mice with immunohistochemical markers: A tool to define developmental lesions. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:555–565. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein GB, Daniel CW. Reversible inhibition of mammary gland growth by transforming growth factor-beta. Science. 1987;237:291–293. doi: 10.1126/science.3474783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein T, Morris JS, Davies CR, Weber-Hall SJ, Duffy MA, Heath VJ, Bell AK, Ferrier RK, Sandilands GP, Gusterson BA. Involution of the mouse mammary gland is associated with an immune cascade and an acute-phase response, involving LBP, CD14 and STAT3. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R75–R91. doi: 10.1186/bcr753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streuli CH, Schmidhauser C, Kobrin M, Bissell MJ, Derynck R. Extracellular matrix regulates expression of the TGF-beta 1 gene. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:253–260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudlow AW, Wilde CJ, Burgoyne RD. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 inhibits casein secretion from differentiating mammary-gland explants but not from lactating mammary cells. Biochem J. 1994;304:333–336. doi: 10.1042/bj3040333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangaraju M, Rudelius M, Bierie B, Raffeld M, Sharan S, Hennighausen L, Huang AM, Sterneck E. C/EBPdelta is a crucial regulator of pro-apoptotic gene expression during mammary gland involution. Development (Cambridge, England) 2005;132:4675–4685. doi: 10.1242/dev.02050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KU, Wall RJ, St-Onge L, Gruss P, Wynshaw-Boris A, Garrett L, Li M, Furth PA, Hennighausen L. Cre-mediated gene deletion in the mammary gland. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4323–4330. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KU, McAllister K, Ward T, Davis B, Wiseman R, Hennighausen L. Spatial and temporal expression of the Cre gene under the control of the MMTV-LTR in different lines of transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 2001;10:545–553. doi: 10.1023/a:1013063514007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YA, Tang B, Robinson G, Hennighausen L, Brodie SG, Deng CX, Wakefield LM. Smad3 in the mammary epithelium has a nonredundant role in the induction of apoptosis, but not in the regulation of proliferation or differentiation by transforming growth factor-beta. Cell Growth Differ. 2002;13:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.