Abstract

Background: Little information is available on the long-term outcomes of patients with localised prostate cancer.

Objective: To examine the long-term survival of patients with localised prostate gland carcinoma T1 - T2, N0, M0 (UICC stage I and II) compared to the normal population.

Design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Regensburg, Germany.

Participants: Data on 2121 patients with histologically-confirmed, localised prostate cancer diagnosed between 1998 and 2007 were extracted from the cancer registry of the tumour centre in Regensburg, Germany.

Measurements: Overall survival rate in the patient cohort was estimated and compared to the expected survival rate of a comparable group in the general population derived from the official life-tables of Germany stratified by age, sex and calendar year.

Results: Ten years after diagnosis, patients with stage I and II localised prostate gland carcinoma had an approximately 10% increase in survival compared to the normal male population (Relative Survival = 110.7%, 95%-CI 106.6 - 114.8%).

Limitations: We did not examine the effect of cancer treatment or cancer aggressiveness on the overall survival of patients. We did not assess the incidence of subsequent non-primary cancers in our patient population or how this incidence affects the patients' follow-up care and survival.

Conclusions: Patients with stage I+II localised prostate gland carcinoma have improved survival compared with the normal male population. This finding cannot be explained solely by the administration of prostate carcinoma treatments, suggesting that men who participate in PSA screening may have better overall health behaviors and care than men who do not participate in screening. Future research should examine how treatment choice, especially an “active surveillance” approach to care, affects survival in these patients more than ten years after diagnosis.

Keywords: prostate cancer, outcomes research, health status, social gradient of prevention, PSA

Introduction

The incidence of prostate cancer has increased in industrialized nations worldwide in the past three decades 1. Today, almost 20% of men over 50 years old will receive a prostate cancer diagnosis, and between 1979 and 2006 the detection of prostate cancer increased among men less than 65 years of age by approximately 4.1-fold 1. These increases can be explained in-part by the implementation of extensive prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening programs and the aging populations of industrialized nations 2,3.

Although PSA testing increases prostate cancer incidence by improving the ability to detect prostate cancer cases in a population, it also allows for the recognition and treatment of prostate cancer in an early stage, thereby reducing the rate of death from prostate cancer 2,4. Due to this shift in the stage at which men receive a prostate cancer diagnosis, wide-scale use of traditional curative treatments for prostate cancer (such as radical prostatectomy), which come with medical and quality of life side-effects, may not be justified. Indeed, the new guidelines of the Germany Society for Urology (DGU) 5 include "active surveillance" as an acceptable therapy option for low-risk prostate cancer, but research is needed on the long-term survival of these patients and the effect of treatment choice on survival before standardized treatment recommendations for localised, low-risk prostate cancer are possible.

There have been limited data available on men with localised prostate gland carcinoma in Europe with which to conduct necessary research on the long-term survival of patents with low-risk prostate cancer 6. The creation of regional cancer registries in the past 10-15 years, including that of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), has provided for the opportunity to close this research gap. In order to investigate the long-term outcomes of patients with localised prostate carcinoma in Germany, we used data from the regional tumour registry in Regensburg, Germany to evaluate the relative survival of patients with localised prostate gland carcinoma, as compared to the standardised age-adjusted survival of the normal Bavarian population.

Methods

We extracted epidemiological and clinical data from the Regensburg regional tumour registry on patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2007 with prostate cancer. The cancer tumour registry of Regensburg is a population-based registry that records the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up care of any known malignancy in cancer patients living in the districts of Oberpfalz and Niederbayern, Bavaria, Germany. The data for the registry are provided by primary care physicians, hospital staff and pathologists from the districts using standardised cancer registry forms. The registry captures more than 90% of all persons diagnosed with cancer located in the two districts, which have a combined population of approximately 2 million residents 6.

All patients included in this study had a histologically-confirmed prostate carcinoma (diagnosis C61), based on the International Classification of Diseases ICD-10 8. The registry record for each patient included the initial clinical and the pathological stage according to the classification of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) 9. We used this classification to select patients with early and locally-limited cancer UICC stages I and/or II, comprising patients with small tumour size (T1 and T2), negative nodal status (N0) and no distant metastasis (M0). Although not part of our primary study objective, we also selected patients with stage III and stage IV prostate cancer to evaluate the relative, long-term survival in patients with later stage prostate carcinoma. We ascertained the life-status of the registry patients using death-certificates and information from the registration offices of the patients' respective resident districts.

We calculated overall survival rates and relative survival rates of the cancer patients at 5 and 10 years post-diagnosis. The cumulative relative survival rate is defined as the ratio of the observed overall survival rate in the patient group and the expected survival rate of a comparable group from the general population matched with respect to age at diagnosis, sex and calendar year of diagnosis. For this comparison the official German life-tables from 1998 to 2007 were used, stratified according to age, sex and calendar year. We applied the software SURVSOFT for calculating overall survival choosing the standard life table (actuarial) method with one-year time intervals and for calculating relative survival choosing the method of Hakulinen in order to estimate expected survival 10. All patients - regardless of length of follow-up - were included. We did not differentiate or control for the types of cancer treatments received by the patients, because we were interested in overall survival independent of treatment choice. Descriptive data analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS V.18.

Results

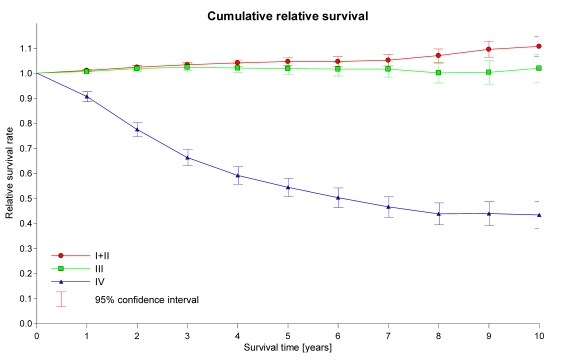

Table 1 shows the numbers, average ages and length of follow-up of the patients included in our analyses. Approximately 51% of all diagnosed tumours in the registry data were stage I+II localised tumours. The average age at diagnosis was 67.2 years (median: 67.6), the average length of follow-up was 6.4 years (median: 6.1). Table 2 and Figure 1 show the results of our overall survival calculations and relative survival analyses. Patients with stage I+II prostate cancer had an approximately 5% increase in 5-year survival compared to the normal population (Relative survival = 104.7%, 95%-CI 103.2 - 106.2%) and an approximately 10% increase in 10-year survival compared with the normal population (Relative Survival = 110.7%, 95%-CI 106.6 - 114.8%; Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 1.

Number, average age and follow-up of patients.

| Sample | Age | Follow-up (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate Cancer Stage (UICC) | N | % | Mean | Median | Mean | Median |

| I+II | 2121 | 50.6% | 67.2 | 67.6 | 6.4 | 6.1 |

| III | 954 | 22.8% | 65.5 | 65.7 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| IV | 1113 | 26.6% | 68.8 | 68.7 | 4.2 | 3.4 |

| Total | 4188 | 100.0% | 67.2 | 67.3 | 5.8 | 5.7 |

UICC = International Union Against Cancer

Table 2.

Overall survival of patients, expected survival of comparable normal population, and relative survival of the patient cohorts at 5- and 10-years post-diagnosis by cancer stage.

| Prostate Cancer Stage (UICC) | Overall Survival of Patient Cohort (%) | Expected Survival of Comparable Normal Population (%) | Relative Survival of Patient Cohort (%)(95%-Confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5Y | 10Y | 5Y | 10Y | 5Y | 10Y | |

| I+II | 90.2 | 76.5 | 86.2 | 69.1 | 104.7(103.2-106.2) | 110.7(106.6-114.8) |

| III | 89.9 | 75.0 | 88.2 | 73.6 | 101.9(99.7-104.2) | 102.0(96.4-107.5) |

| IV | 44.9 | 28.2 | 82.6 | 64.9 | 54.4(50.7-58.0) | 43.4(38.1-48.7) |

| Total | 78.2 | 63.0 | 85.7 | 69.0 | 91.2(89.7-92.7) | 91.4(88.4-94.4) |

UICC = International Union Against Cancer; Y = Number of years post-diagnosis

Figure 1.

Relative survival rates for the prostate cancer stage I+II, III and IV patient cohort.

Patients with stage III prostate cancer did not have significantly different 5-year or 10-year survival rates than the normal population (Relative Survival = 101.9%, 95%-CI 99.7 - 104.2% and 102.0%, 95%-CI 96.4 - 107.5%, respectively; Table 2, Figure 1), while patients with stage IV prostate cancer had significant and clear 5-year and 10-year survival disadvantages compared to the normal population (Relative Survival = 54.4%, 95%-CI 50.7 - 58.0% and 43.4%, 95%-CI 38.1 - 48.7%, respectively; Table 2, Figure 1).

Discussion

Our analyses showed that patients with stage I+II localised prostate gland carcinoma have improved survival compared to the normal male population, and this relative survival advantage appears only 2-3 years after diagnosis (Figure 1). This finding cannot be explained definitively by the administration of prostate gland carcinoma treatments (e.g., radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy), which have been shown to result in a survival advantage only after several years 11,12,13.

We suggest three primary explanations for our findings. First, as described in previous research, relatively healthy men take advantage of PSA-supported preventive measures and show reduced morbidity and improved survival compared to men who do not participate in PSA testing 14. Additionally, we know from the 2008 work of Fröhner et al. that in men 63 to 69 years of age increased comorbidity is a strong predictor of 10-year mortality in men receiving radical prostatectomy 15. Our results support these findings by suggesting that the health of men who undergo PSA-testing, especially those in the 50-70 year-old age range, is better overall (i.e., lower comorbidity) than that of men who do not participate in PSA screening. Second, research has shown that a cancer diagnosis can be a “teachable moment” that encourages patients to adopt better health behaviors 16,17. The men in our sample who were diagnosed with stage I or II prostate cancer may have made more positive health choices compared to the general population in the first few years after their diagnosis. Third, the observed improved survival may result not only from the superior health-consciousness and behaviors of cancer patients, but also from socioeconomic advantages (e.g., higher levels of education and income) that make one more like to receive secondary prevention outreach by health care providers and the media 18,19,20. The socioeconomic disparities in secondary prevention outreach and up-take are cited as a major weakness of PSA screening systems. Furthermore it is well possible that physicians exercise a more careful patient selection for prostate cancer screening.

The goal of treatment for prostate gland carcinoma should be the effective delivery of care to every diagnosed patient, and this care must take into account each patient's individual needs, living conditions, and tumour biology. Our finding that men with stage I+II prostate cancer have survival advantages independent of treatment choice suggests that the current standards of care in Germany—which result in almost 70% of prostate cancer patients under the age of 70 receiving radical prostatectomy—should change to include less invasive methods of treatment for cancers at low risk of progression 21. Accordingly, several European treatment guidelines now include “active surveillance” as an evidence-based method of treatment for localised, low-risk prostate carcinoma 5.

Limitations to our study include the fact that we did not examine the effect of individual, evidence-based treatments for localised prostate gland carcinoma or cancer aggressiveness (e.g., Gleason score) 21 on the overall survival of patients. We also did not evaluate whether all patients with stage I+II prostate cancer included in the study had underwent PSA screening to confirm our conclusion that the patients' survival advantage related to their participation in PSA testing. Lastly, we did not assess the incidence of subsequent non-primary cancers in our patient population or how this incidence affects the patients' follow-up care and survival 21. We plan to conduct future analyses to examine these questions in the German population.

Conclusion

Patients with localised, stage I+II prostate gland carcinoma demonstrated improved long-term health compared to the normal population, regardless of the treatment received during the first ten years after diagnosis. The finding suggests that that men who participate in PSA screening may have better overall health behaviors and care than men who do not participate in screening and that men who receive a cancer diagnosis may make positive health behavior changes after their diagnosis that improve their long-term survival. Future research should examine how treatment choice, especially an “active surveillance” approach to care, affects survival in these patients more than ten years after diagnosis. Research should also evaluate the long-term survival impact of socioeconomic disparities in the receipt of prostate cancer secondary prevention outreach and services.

References

- 1.SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Feuer EJ, Huang L, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Lewis DR, Eisner MP, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK; http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ. et al. Screening and Prostate-Cancer Mortality in a Randomized European Study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–1328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borre M, Nerstrøm B, Overgaard J. The natural history of prostate carcinoma based on a Danish cancer population treated with no intent to cure. Cancer. 1997;80:917–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratliff TL. et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1156–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DGU. S3-Leitlinie Prostatakarzinom, Version 1,0. DGU. 2009.

- 6.Hamilton AS, Albertsen PC, Johnson TK. et al. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005;293(17):2095–101. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klotz T, Hofstadter F, Gerken M. Interdisciplinary oncologic after-care exemplified by second primary tumours after bladder carcinoma. Urologe A. 2003;42:1485–1490. doi: 10.1007/s00120-003-0396-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) World Health Organization. 1992.

- 9.Sobin LH, Wittekind CL. TNM classification of malignant tumours, 6th edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geiss K, Meyer M, Radespiel-Tröger M, Gefeller O. SURVSOFT—Software for nonparametric survival analysis. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2009;96(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fröhner M, Koch R, Litz RJ, Hakenberg O, Oehlschlaeger S, Wirth M. Interaction Between Age and Comorbidity as Predictors of Mortality After Radical Prostatectomy. J Urol. 2008;179:1823–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fröhner M, Koch R, Litz RJ. et al. Detailed Analysis of Charlson Comorbidity Score as Predictor of Mortality After Radical Prostatectomy. Urology. 2008;72:1252–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ketchandji M, Kuo JF, Shahinian VB, Goodwin JS. Cause of death in older men after the diagnosis of prostate cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:24–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeliadt SB, Etzioni R, Ramsey SD, Penson DF, Potosky AL. Trends in treatment costs for localised prostate cancer: the healthy screenee effect. Med Care. 2007 Feb;45(2):154–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000241044.09778.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fröhner M, Koch R, Litz RJ, Hakenberg O, Oehlschlaeger S, Wirth M. Interaction Between Age and Comorbidity as Predictors of Mortality After Radical Prostatectomy. J Urol. 2008;179:1823–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBride CM, Scholes D, Grothaus LC, Curry SJ, Ludman E, Albright J. Evaluation of a minimal self-help smoking cessation intervention following cervical cancer screening. Prev Med. 1999 Aug;29(2):133–8. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humpel N, Magee C, Jones SC. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on the health behaviors of cancer survivors and their family and friends. Support Care Cancer. 2007 Jun;15(6):621–30. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hurrelmann K, Klotz T, Haisch J. Lehrbuch Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. Bern: Huber; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lampert T Tabakkonsum, sportliche Inaktivität und Adipositas Dtsch Arztebl Int 20101071-21–7. 20090874 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raffle A, Muir Gray JA. Screening - Durchführung und Nutzen von Vorsorgeuntersuchungen. Bern, Göttingen, Toronto, Seattle: Huber; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weißbach L, Altwein J. Aktive Überwachung oder aktive Therapie beim lokalen Prostatakarzinom? Dtsch Ärztebl. 2009;106:371–376. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gleason DF. The Veteran's Administration Cooperative Urologic Research Group: histologic grading and clinical staging of prostatic carcinoma. In: Tannenbaum M, editor. Urologic Pathology: The Prostate. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1977. pp. 171–198. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathers MJ, Zumbe J, Wyler S, Roth S, Gerken M, Hofstädter F, Klotz T. Is there evidence for a multidisciplinary follow-up after urological cancer? An evaluation of subsequent cancers. World J Urol. 2008 Jun;26(3):251–6. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]