Extraadrenal pheochromocytomas are rare and can present in difficult locations. In this case, the da Vinci robot was used for the safe management of this perihilar mass.

Keywords: Pheochromocytoma, Extra-adrenal, Retroperitoneal mass, da Vinci, Robotic, Laparoscopic, Renal hilum

Abstract

Background:

Extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas are rare. Minimally invasive techniques have been utilized for incidentally discovered masses with successful results.

Methods:

We present a case of a 64-year-old female with a 3.5-cm mass located between her left renal artery and vein, treated by a 4-port robot-assisted transperitoneal laparoscopic approach.

Results:

Careful dissection of the tumor away from the renal hilum was accomplished without major vascular injury. A pedicle to the tumor was identified and ligated. The pathology demonstrated a benign pheochromocytoma. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a peri-hilar excision of a pheochromocytoma using this approach.

Conclusion:

Extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas are rare and can present in difficult locations. While surgical excision may be challenging, the da Vinci Robot may be used effectively and safely for the treatment of these perihilar masses.

INTRODUCTION

Extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas are rare tumors found in the general population. When discovered, they are usually within the Organ of Zuckerkandl, a conglomerate of neuroendocrine tissue located along the aorta. We present the management of a 64-year-old female with an extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma found in an unusual location between the left renal artery and vein.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 64-year-old, white female with a recent history of cardiac catheterization who presented with a retroperitoneal mass located between her left renal artery and vein (Figure 1). Her medical history includes mild hypertension controlled with amlodipine. Her recent cardiac stents necessitated daily aspirin and clopidogrel. The mass was diagnosed on an abdominal CT performed one year earlier for unexplained abdominal pain. The well-circumscribed mass was initially 2.0cm in diameter and enhanced with IV contrast administration. There was no lymphadenopathy noted. On serial CTs, the mass grew to a size of 3.5cm (Figure 1). This prompted a percutaneous biopsy that was inconclusive but complicated by a retroperitoneal hematoma. Postbiopsy hypertension was not noted, and the patient did not require a blood transfusion. Due to the increasing size of the mass, however, a decision was made to perform an excisional biopsy of the mass using a robot-assisted laparoscopic approach. The patient exhibited none of the usual signs or symptoms of a pheochromocytoma.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT in the axial plane, showing the mass at the left renal hilum.

Surgical Technique

No significant medical modifications were performed, because the patient had no stigmata of a pheochromocytoma. The procedure was performed with the patient in the right lateral decubitus position. A transperitoneal approach was used, and insufflation was obtained using a Veress needle technique. A 12-mm camera port was placed lateral to the rectus muscle at the level of the umbilicus. Two 8-mm robotic trocars were placed: one in the left lower quadrant above the anterior superior iliac spine and the other in the upper left quadrant midline between the xiphoid and the umbilicus, approximately 14cm apart. A 5-mm assistant port was placed midline just below the umbilicus.

The left colon was mobilized medially. The gonadal vein was traced to the level of the renal vein where the mass was clearly visible. Careful dissection enabled excellent visualization of the gonadal, ascending lumbar, and adrenal vein branches of the left renal vein. The mass was trapped behind the left renal vein and invested by venous tributaries (Figure 2). The gonadal vein was ligated and divided to create a window where the mass could be removed from behind the vein. Two other small veins were divided. During the dissection, one of these branches was avulsed from the main renal vein and repaired with a figure of eight 4-0 Prolene stitch. The mass was then mobilized from behind the vein. A small vascular pedicle was noted and clipped with titanium clips, and the mass was excised en bloc (Figure 3). Hemostasis was ensured, and SugiFLO hemostatic matrix (Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, NJ) was applied to the surgical bed. The mass was placed into a laparoscopic entrapment sac and sent for pathologic examination.

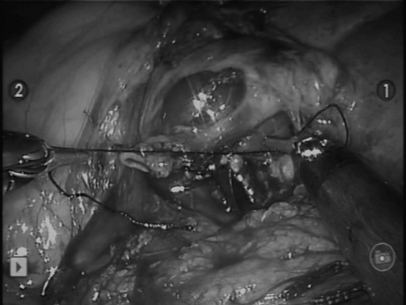

Figure 2.

View of mass posterior to the left renal vein. A posterior lumbar vessel was encountered and controlled accordingly.

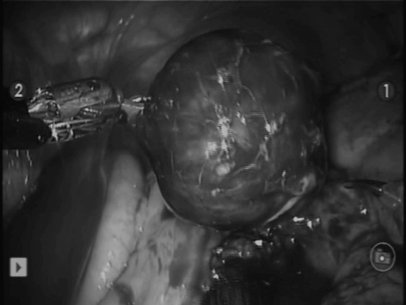

Figure 3.

The mass completely mobilized.

The patient tolerated the procedure very well and had an uneventful postoperative course. She was discharged home on postoperative day one. Final surgical pathology demonstrated a 3.4x2.9x2.0-cm pheochromocytoma without evidence of malignancy.

DISCUSSION

Pheochromocytomas are rare tumors consisting of catecholamine-producing chromaffin cells usually arising from the adrenal medulla. In 15% to 25% of cases, they may arise from the embryological adrenal remnants referred to as extra-adrenal paragangliomas.1–4 These are found approximately 4 times as often in children as in adults.5 In adults, 85% of these occur in the abdomen,6 mainly along the para-spinal sympathetic ganglion and organ of Zuckerkandl.

Clinically, pheochromocytomas may occur along with hypertension, tachycardia, pallor, and headache.4,7 Hypertension is classically paroxysmal, with or without sustained hypertension. Conversely, the patient may be normotensive without a history of hypertension, particularly in incidentalomas.8 Given the exponential increase in imaging tests ordered in recent years, 25% of all discovered pheochromocytomas are incidental findings. The number of normotensive patients with pheochromocytomas has increased significantly as well.8–11

While most pheochromocytomas occur sporadically, there is significant evidence of a genetic component, particularly within familial syndromes, such as von Hippel-Lindau, neurofibromatosis type 1, and multiple endocrine neoplasia 2A and 2B.12 Recent advances in genetic analysis have demonstrated hereditary causes of paragangliomas as well, such as mutations in the enzyme succinate dehydrogenase.13,14

There is growing interest in minimally invasive approaches for the treatment of small tumors discovered incidentally on imaging. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy has been reported for pheochromocytoma.15 Because it is a much less common entity, significantly less data are available on such techniques for extra-adrenal disease. Given the difficult location of this mass, a robot-assisted laparoscopic approach was used. The minor vascular repair was performed without difficulty. This may have proven to be a challenge had a standard laparoscopic procedure been used.

Our port configuration enabled easy access to the mass as well as the lower pole of the kidney. Additionally, the 3-dimensional vision afforded clear delineation of the vascular anatomy investing the tumor. The renal vein and all tributaries caused very little difficulty during the dissection.

A consideration was made to excise this mass from a retroperitoneal approach. This may have potentially avoided the venous tributaries encountered during the dissection. However, the increased working room afforded by the transperitoneal approach proved to be both safe and efficacious.

CONCLUSION

This is to our knowledge the first reported case of a robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of a peri-hilar pheochromocytoma. The benefits of the da Vinci Surgical System including the wristed instrumentation and 3-dimensional vision were felt to be useful in the successful completion of this case without renal loss or conversion to open excision.

Contributor Information

Todd Lehrfeld, Somers Point, New Jersey, USA..

Rachel Natale, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA..

Saurabh Sharma, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA..

Pierre J. Mendoza, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA..

Charles W. Schwab, II, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA..

David I. Lee, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA..

References:

- 1. Whalen RK, Althausen AF, Daniels GH. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma. J Urol. 1992;147(1):1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pacak K, Linehan WM, Eisenhofer G, Walther MM, Goldstein DS. Recent advances in genetics, diagnosis, localization, and treatment of pheochromocytoma. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(4):315–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Erickson D, Kudva YC, Ebersold MJ, et al. Benign paragangliomas: clinical presentation and treatment outcomes in 236 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(11):5210–5216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366(9486):665–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gifford RW, Jr., Manger WM, Bravo EL. Pheochromocytoma. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23(2):387–404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Riordain DS, Young WF, Jr., Grant CS, Carney JA, van Heerden JA. Clinical spectrum and outcome of functional extraadrenal paraganglioma. World J Surg. 1996;20(7):916–921, discussion 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Werbel SS, Ober KP. Pheochromocytoma. Update on diagnosis, localization, and management. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79(1):131–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mantero F, Terzolo M, Arnaldi G, et al. A survey on adrenal incidentaloma in Italy. Study Group on Adrenal Tumors of the Italian Society of Endocrinology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(2):637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mansmann G, Lau J, Balk E, Rothberg M, Miyachi Y, Bornstein SR. The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(2):309–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baguet JP, Hammer L, Mazzuco TL, et al. Circumstances of discovery of phaeochromocytoma: a retrospective study of 41 consecutive patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150(5):681–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amar L, Servais A, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Zinzindohoue F, Chatellier G, Plouin PF. Year of diagnosis, features at presentation, and risk of recurrence in patients with pheochromocytoma or secreting paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):2110–2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bryant J, Farmer J, Kessler LJ, Townsend RR, Nathanson KL. Pheochromocytoma: the expanding genetic differential diagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(16):1196–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neumann HP, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, et al. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA. 2004;292(8):943–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Favier J, Rustin P, et al. Mutations in the SDHB gene are associated with extra-adrenal and/or malignant phaeochromocytomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63(17):5615–5621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Faria EF, Andreoni C, Krebs RK, et al. Advances in pheochromocytoma management in the era of laparoscopy. J Endourol. 2007;21(11):1303–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]