Abstract

This study examines the relationships among race, education, formal as well as informal involvement in the church, and God-mediated control. Formal involvement in the church was assessed by the frequency of attendance at worship services, Bible study groups, and prayer groups. Informal involvement was measured with an index of spiritual support provided by fellow church members. Data from a nationwide longitudinal survey of older people suggest that both formal and informal church involvement tend to sustain feelings of God-mediated control over time. The findings further reveal that compared to older whites, older African Americans are more likely to have stronger feelings of God-mediated control at the baseline survey and older blacks are more likely to sustain their sense of God-mediated control over time. In contrast, the data suggest that education is not significantly related to feelings of God-mediated control.

Introduction

The construct of control has occupied a central place in social and behavioral research for decades (Zarit, Pearlin, and Schaie 2002). In fact, some investigators claim it may be a more important determinant of psychological well-being than any other psychosocial factor (Ross and Sastry 1999). Although numerous scales have been devised to assess feelings of personal control (e.g., locus of control, self-efficacy, mastery), these various measures, nevertheless, share a common conceptual core. Embedded in each index is the notion that individuals with a strong sense of personal control believe the things that happen to them are responsive to and contingent upon their own choices, efforts, and actions (Ross and Sastry 1999). In contrast, people with a weak sense of personal control believe that events in their lives are shaped by forces outside their influence, and they feel they are not able to influence or regulate the things that happen to them.

The construct of control has not gone unnoticed in research on religion. In fact, scholars have extended research on control in a relatively unique way by introducing the notion of God-mediated control (Berrenberg 1987). Two approaches have been taken to define and measure this construct. The first is found in the work of Welton et al. (1996). They maintain that control over an individual's life is entirely in the hands of God. This perspective is reflected in the following item that was taken from their scale: “My life is primarily controlled by God.” A similar approach is taken by Schieman, Pudrovska, and Milkie (2005) to measure their notion of divine control: “God has decided what your life shall be.” In contrast, Krause (2005) provides a second approach to assessing God-mediated control. According to his perspective, people do not completely surrender control of their lives to God. Instead, they work collaboratively with God to master the social environment. This view is captured in the following indicator in the scale used by Krause: “All things are possible when I work together with God.” The notion of working collaboratively with God is also embedded in Pargament's religious coping scale (Pargament, Koenig, and Perez 2000). Although both approaches to assessing God-mediated control have produced valuable insights, the analyses in this study focus on efforts to exercise control in life by working collaboratively with God.1

Research reveals that people with a strong sense of God-mediated control tend to have higher self-esteem than individuals who do not have a strong sense of God-mediated control (Krause 2005). Schieman et al. (2005) also found that divine control bolsters feelings of self-worth, but their analyses suggest this is true for some study participants (i.e., older black women), but not for others (i.e., older white men). In addition, Krause (2005) reports that a strong sense of God-mediated control is associated with greater life satisfaction, more optimism, and lower levels of death anxiety. Given these findings, it is important to learn more about how feelings of God-mediated control arise in the first place. Simply put, we need studies that treat God-mediated control as a dependent variable.

There appears to be very little research on the factors that influence feelings of God-mediated control in late life. However, some preliminary insights are found in the study by Krause (2005). This work suggests that feelings of God-mediated control are influenced by several factors, including race and involvement in the church. More specifically, the data reveal that stronger feelings of God-mediated control are found among older African Americans than among older whites. In addition, Krause reports that people who attend church more often tend to have stronger feelings of God-mediated control than older adults who attend worship services less frequently. Although these findings provide some potentially useful insight into how feelings of God-mediated control may arise, it is difficult to figure out how to interpret them. More specifically, little is known about why older blacks have a stronger sense of God-mediated control than older whites and it is not clear how involvement in formal religious activities may increase feelings of God-mediated control. In addition, the study by Krause (2005) is limited by the fact that it is based on cross-sectional data. As a result, it was not possible to assess the effects of race and church involvement on feelings of God-mediated control over time.

The purpose of this study is to address these issues by developing and testing a latent variable model that explores how feelings of God-mediated control arise and are sustained or maintained over time. This conceptual scheme is evaluated with data from a recent nationwide longitudinal survey of older adults.

Exploring the Factors that Shape God-Mediated Control

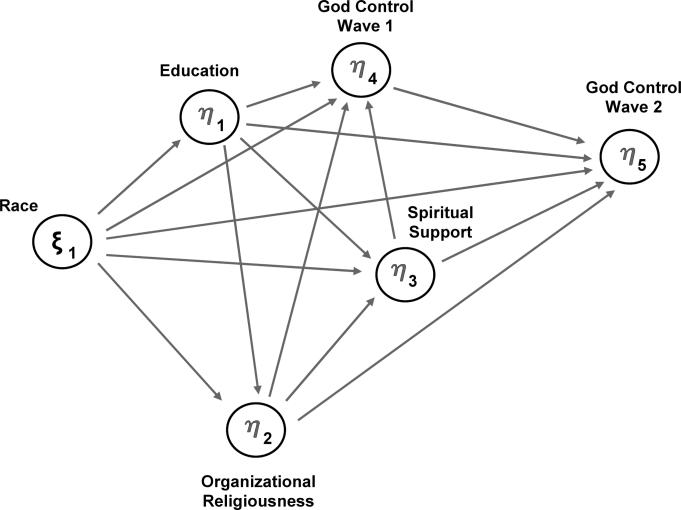

The latent variable model that was developed for this study is depicted in Figure 1. Before turning to a discussion of the substantive relationships in this model, it is important to point out that the relationships among the constructs in this figure were evaluated after the effects of age and sex were controlled statistically. Two social factors figure prominently in Figure 1: the first deals with social structural elements (i.e., race and education), whereas the second has to do with formal and informal involvement in the church. The basic idea is that feelings of God-mediated control are shaped by social structural factors and the effects of these social structural factors are mediated by involvement in the church. The core theoretical thrust of this conceptual scheme is captured in the following linkages: (1) older blacks will have lower levels of educational attainment than older whites; (2) older African Americans and older people with fewer years of schooling will be more involved in formal church activities; (3) older people with greater involvement in the church will be more likely to receive spiritual support from fellow church members; and (4) greater spiritual support is associated with stronger feelings of God-mediated control.

FIGURE 1.

A CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF GOD-MEDIATED CONTROL

A key feature of the model in Figure 1 is that the impact of the social structural factors and the measures of religious involvement are assessed on both contemporaneous (Wave 1) as well as lagged measures of God-mediated control (Wave 2). This makes it possible to see whether the social structural and religious involvement variables are associated with feelings of God-mediated control at the inception of the study and if these constructs influence God-mediated control over time. The theoretical rationale for the relationship among these linkages is provided below. Following this, an effort is made to show why it is important to explore factors that influence God-mediated control in samples composed of older people.

Race and Socioeconomic Status

Researchers have argued for some time that individuals who are socially and economically disadvantaged are especially likely to turn to, and benefit from, religion (Stark and Bainbridge 1987). More specifically, turning to religious institutions and beliefs provides a way to offset the effects of being unable to obtain the economic, social, and psychological benefits associated with full participation in secular institutions (e.g., the workplace). Race and education are included in Figure 1 in order to test this deprivation-compensation hypothesis. Education is included in this model to represent socioeconomic status (SES). Researchers typically assess SES with measures of education, income, or occupational prestige. However, there are three reasons why education may be the most important when studying older people. First, most older adults are retired, and many older women were never employed outside the home. As Mirowsky and Ross (2003) point out, this makes occupational prestige a less desirable way of evaluating SES because it is difficult to assign occupational prestige scores to a significant number of older study participants. Second, research by Crystal (1986) reveals that self-reports of income among older people contain a considerable amount of measurement error. In fact, the findings from his study indicate that income may be underreported by as much as 46 percent among older people. Third, based on their extensive review of SES measures, Mirowsky and Ross (2003:30) conclude that “[e]ducation is the key to one's place in the stratification system.”

If both race and education can affect religious outcomes, then it is important to know which factor has the greatest influence. Researchers have wrestled with disentangling the effects of race and SES for some time (Kessler and Neighbors 1986). But rather than pitting one measure against the other, the model depicted in Figure 1 specifies that there is a causal relationship between them. Consistent with the findings from a number of surveys (e.g., Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics 2004), it is hypothesized that older African Americans will have lower levels of educational attainment than older whites. This is especially true for the cohort of older blacks because they went through the educational system at a time when institutional racism was more overt than it is today. By comparing and contrasting the direct effects of race on God-mediated control with the indirect effects that operate through education, it will be possible to tease out the way in which these two social structural factors shape feelings of God-mediated control in late life.

Socioeconomic Status and Organizational Religiousness

Organizational religiousness reflects participation in the official activities of religious institutions. This construct is measured in Figure 1 with three indicators: the frequency of attendance at church worship services, Bible study groups, and prayer groups. This way of measuring involvement in religious institutions has been used by researchers for a number of years (e.g., Mindel and Vaughn 1978). A well-developed literature suggests that older blacks are much more likely to be involved in religious institutions than older whites (see Taylor, Chatters, and Levin 2004 for a review of this research). This reflects the fact that the church has been the central institution in the black community for over a century (Du Bois 2000). Moreover, consistent with the rationale provided in the “Race and Socioeconomic Status” section, it is predicted that older people from lower SES groups will be more involved in official church activities than upper SES elders.

Organizational Religiousness, Spiritual Support, and God-Mediated Control

It is hypothesized in Figure 1 that formal as well as informal involvement in the church is associated with feelings of God-mediated control at the baseline as well as the follow-up survey. The rationale for exploring these contemporaneous and lagged relationships is discussed below.

Influences on God-Mediated Control at the Baseline Interview

Involvement in formal church activities may be associated with God-mediated control at the baseline survey for a number of reasons. For example, messages and lessons that are embedded in worship services may underscore the advantages of working together with God to solve problems and reach goals in life. The same messages may be reinforced in the singing of hymns as well as in congregational prayers that are often part of formal worship services. In much the same way, feelings of God-mediated control may also be reinforced by participation in Bible study and prayer groups. Some evidence of this may be found in Wuthnow's (1994) insightful examination of Bible study and prayer groups. Although Wuthnow did not discuss God-mediated control explicitly, he found that participants in Bible study and prayer groups nevertheless mentioned issues that are consistent with the spirit and essence of this construct. As one woman in his study indicated, “I have Christ in my heart . . . Now that I have him and know he's there for me, he's helping me get through the tough times, making me deal with issues and just confront things and face things, and I know he's going to be there to get me through it” (Wuthnow 1994:237).

But the influence of church involvement on feelings of God-mediated control may not be restricted to participation in formal activities alone. A number of studies suggest that rich informal social networks tend to flourish in religious institutions and these networks may be especially close and supportive (see Ellison and Levin 1998 for a review of this research). This research further reveals that informal social ties that arise in religious institutions serve a number of important functions, including the provision of emotional support and tangible help (Taylor et al. 2004). However, as Krause (2002b) points out, informal relationships at church may be an important source of religious beliefs as well. In order to study this function, he developed measures of informal spiritual support, which refer to assistance provided for the specific purpose of increasing religious commitments, beliefs, and behaviors of a fellow church member. Spiritual support may be exchanged in a number of different ways. For example, church members may share their own religious experiences with fellow parishioners, or show them how to apply their religious beliefs in daily life. By providing this kind of assistance, church members may become an important source of God-mediated control. This notion is consistent with the widely cited theory of religion that was devised by Stark and Finke (2000). These scholars maintain that interaction with fellow believers exerts an important influence on a wide range of religious beliefs. Referring to religious belief systems as “religious explanations,” these researchers propose that “[a]n individual's confidence in religious explanations is strengthened to the extent that others express their confidence in them” (Stark and Finke 2000:107).

The view that many facets of religion are inherently social in nature is hardly new. Writing over 100 years ago, Simmel ([1898] 1997:108), a classic social theorist, maintained that “[t]he faith that has come to be regarded as the essence and substance of religion is first of all a relationship between human beings” (emphasis in the original). A similar view may be found in the work of Josiah Royce, a leading philosopher of his time and a close friend of William James. In 1912, Royce wrote a book that was designed to address what he felt were inaccuracies in James's classic treatise on religion (Varieties of Religious Experience [1902] 1985). Instead of arising from the depths of the unconscious as James maintained, Royce ([1912] 2001:58) argued that religious experiences, and the beliefs that are based upon them, are the product of a social process: “our social experience is our principle source of religious insight. And the salvation that this brings to our knowledge is salvation through the fostering of human brotherhood.”

The model depicted in Figure 1 helps flesh out these classical theoretical insights by grounding them in a more concrete and specific context (i.e., the church), and by showing how they affect a specific kind of religious belief (i.e., God-mediated control). Moreover, by comparing and contrasting the influence of both formal and informal social influences in the church, it is possible to more clearly identify the precise factors that are at work. There are three possibilities. First, only formal involvement in the church may matter. Second, spiritual support from fellow church members may be the most critical factor. Third, both factors may work synergistically to promote feelings of God-mediated control.

Influences on God-Mediated Control Over Time

A key advantage of the model depicted in Figure 1 arises from the fact that it focuses on the interface between formal and informal involvement in church and feelings of God-mediated control over time. This type of analysis brings a subtle issue about the relationships among these constructs to the foreground. As Kessler and Greenberg (1981) pointed out some time ago, a positive relationship between factors such as spiritual and God-mediated control over time may reflect not one, but two potentially important influences. First, spiritual support may help sustain feelings of God-mediated control over time. Second, spiritual support from fellow church members may be associated with an increase in God-mediated control over time. It is hypothesized in this study that formal and informal involvement in the church are more likely to sustain than increase feelings of God-mediated control. This hypothesis is based on the following rationale. Research by Krause and Wulff (2005) reveals that older people have typically attended the place where they worship for a longer period of time than younger adults. Consequently, the social relationships that older people have formed with fellow church members are likely to have been in place for a fairly long time. Although social relationships in the church may have initially increased an older person's sense of God-mediated control, it is unlikely that these social ties will continue to increase God-mediated control indefinitely. Instead, once social relationships become stable and ongoing, significant others will be more likely to help older people sustain or maintain a sense of God-mediated control. The same rationale applies to formal involvement in the church. Initially, attending worship services, Bible study groups, and prayer groups may increase an older person's sense of God-mediated control. But once a high level of God-mediated control has been attained, participation in formal church activities should be more likely to sustain gains in God-mediated control that were realized at an earlier point in time.

Exploring God-Mediated Control in Late Life

As noted above, the data for this study come from a nationwide survey of older people. Although younger adults were not included in the sample, it may be helpful to discuss why it is important to examine the relationship between church involvement and God-mediated control specifically in late life.

A number of studies conducted in secular settings indicate that global or generalized feelings of personal control tend to decline with advancing age (e.g., Mirowsky 1995). This decline in control may be due to the loss of physical as well as cognitive capabilities. A key issue for gerontologists has been to figure out how people cope with the progressive loss of personal control as they grow older. Some insight into this issue is provided by Schulz and Heckhausen (1996). These investigators argue that as people grow older, they relinquish control in some areas of life so that control may be maintained in other areas. This means, for example, that an older woman may turn over control of her finances to her son so she can concentrate her efforts on maintaining a sense of control over other domains of life that are important to her.

Although the insights provided by Schulz and Heckhausen (1996) are important, their theoretical perspective does not acknowledge all the options that are available to older people. Instead of giving up control over some areas of life completely, older adults may work collaboratively with trusted others to help ensure that problems are overcome, role obligations are met, and plans are brought to fruition. This notion of collaborative control is consistent with Bandura's (1995) work on collective self-efficacy. It is especially important for the purposes of this study to note that even though discussions of turning control over to trusted others typically focus on a spouse or grown child, there is no reason why God might not be included among trusted others as well. In fact, there is reason to believe that older adults may be more likely than younger adults to rely on God-mediated control beliefs. Findings from a number of surveys reveal that older adults are more likely than younger individuals to attend church services, read the Bible, pray, and believe that religion is important in their lives (Gallup and Lindsay 1999; Levin and Taylor 1997). This suggests that if secular dimensions of control decline with advancing age, and involvement in religion increases as people grow older, then perhaps people may be especially inclined to rely on God-mediated control beliefs in late life. An alternative interpretation is that rather than reflecting the influence of age per se, greater levels of involvement in religion among older people arise from cohort effects. Nevertheless, if either age or cohort effects promote stronger feelings of God-mediated control, these effects should be especially evident in samples like the one used in this study.

Method

Sample

The data for this study come from a nationwide longitudinal survey of older whites and older African Americans. The study population was defined at the baseline survey as all household residents who were either black or white, noninstitutionalized, English-speaking, and at least 66 years of age. Geographically, the study population was restricted to eligible persons residing in the coterminous United States (i.e., residents of Alaska and Hawaii were excluded). Finally, the study population was restricted to currently practicing Christians, individuals who were Christian in the past but no longer practice any religion, and people who were not affiliated with any faith at any point in their lifetime. This study was designed to explore a range of issues involving religion. As a result, individuals who practice a religion other than Christianity were excluded because the members of the research team felt it would be too difficult to devise a comprehensive battery of religion measures that would be suitable for individuals of all faiths.

The sampling frame for this study consisted of all eligible persons contained in the beneficiary list maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). A five-step process was used to draw the sample from the CMS files. A detailed discussion of these steps is provided by Krause (2002b).

Interviewing for the baseline survey took place in 2001. The data collection was performed by Harris Interactive (New York). A total of 1,500 interviews were completed. Elderly blacks were oversampled so that sufficient statistical power would be available to assess race differences in religion. As a result, the Wave 1 sample consisted of 748 older whites and 752 older African Americans. The overall response rate for the Wave 1 interviews was 62 percent.

The Wave 2 survey was conducted in 2004. Once again, the surveys were administered by Harris Interactive. A total of 1,024 of the original 1,500 study participants were reinterviewed successfully, 75 refused to participate, 112 could not be located, 70 were too ill to participate, 11 had moved to a nursing home, and 208 were deceased. Not counting those who had died or were placed in a nursing home, the reinterview rate for the Wave 2 survey was 80 percent.

The measure of spiritual support that is used in this study assesses assistance that study participants received from fellow church members. However, it did not make sense to ask older people questions about church-based spiritual support if they either never go to church or attend worship services only rarely. Consequently, the spiritual support items were not administered during the Wave 1 survey to 374 people who went to church no more than twice a year. After using listwise deletion of cases to deal with item nonresponse, the analyses presented below are based on 661 cases. Preliminary analysis revealed that the average age of the people in this group was 74.023 years (SD = 5.897 years) at the baseline survey. Approximately 36 percent were older men. The older adults in this group reported they had successfully completed an average of 11.832 years of schooling (SD = 3.412 years). Finally, approximately 46 percent of the sample comprised older whites. These descriptive data, as well as the analyses that follow, have been weighted. These weights were designed so that sample data on age, sex, education, and region of the country would match the data in the most recent Census (more detail about the sample weighting procedures may be obtained by contacting the author).

Measures

Table 1 contains the survey items that are analyzed and presented below. The procedures used to code these indicators are provided in the footnotes of this table.

TABLE 1.

CORE STUDY MEASURES

| 1. God-Mediated Control (Waves 1 and 2)a |

| A. I rely on God to help me control my life. |

| B. I can succeed with God's help. |

| C. All things are possible when I work together with God. |

| 2. Organizational Religiousness (Wave 1)b |

| A. How often do you attend religious services? |

| B. How often do you attend adult Sunday School or Bible study groups? |

| C. How often do you participate in prayer groups that are not part of regular worship services or Bible study groups? |

| 3. Spiritual Supportc |

| A. Not counting Bible study groups, prayer groups, or church services, how often does someone in your congregation share their own religious experiences with you? |

| B. Not counting Bible study groups, prayer groups, or church services, how often do the examples set by others in your congregation help you lead a better religious life? |

| C. Not counting Bible study groups, prayer groups, or church services, how often does someone in your congregation help you to know God better? |

Responses to these items were scored in the following manner (coding in parentheses): strongly disagree (1); disagree (2); agree (3); strongly agree (4).

Responses to these items were scored in the following manner: never (1); less than once a year (2); about once or twice a year (3); several times a year (4); about once a month (5); 2–3 times a month (6); nearly every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9).

Responses to these items were scored in the following manner: never (1); once in a while (2); fairly often (3); very often (4).

God-Mediated Control

Identical measures of God-mediated control were administered in the baseline and follow-up interviews. The first two indicators were taken from the work of Berrenberg (1987). The third item was devised especially for this study using the extensive item-development strategy discussed by Krause (2002a). The items are coded so that a high score reflects a greater sense of God-mediated control. The mean God-mediated control score at the baseline interview is 10.569 (SD = 1.594) and the mean at the follow-up survey is 10.704 (SD = 1.495).

Organizational Religiousness

As shown in Table 1, formal involvement in the church is measured with a composite that is formed from three indicators that assess the frequency of attendance at worship services, Bible study groups, and prayer groups. The three indicators come from the Wave 1 survey. A high score reflects more frequent participation in formal church activities. The mean of the organizational religious measure is 15.105 (SD = 5.984).

Spiritual Support

Three items were administered at the Wave 1 survey to measure spiritual support from fellow church members. These indicators were developed especially for this study (see Krause 2002a for a detailed discussion of this item-development strategy). These questions ask respondents whether fellow church members share their own religious experiences with them, whether they help them lead a better religious life, and whether fellow parishioners help them get to know God better. Respondents were instructed to exclude support received from people during Bible study groups, prayer groups, or worship services when answering these questions. By ruling out spiritual support that may have been provided during formal church activities, this measurement strategy makes it possible to differentiate between the influence of formal and informal aspects of church involvement. A high score denotes more frequent spiritual support. The mean of this brief spiritual support index is 7.621 (SD = 2.605).

Social Structure

Indicators of race and education serve as key markers of social structural influences. Race was measured with a binary variable that compares older whites (scored 1) with older African Americans (scored 0). In contrast, education is scored in a continuous format reflecting the total number of years of schooling that was completed successfully.

Demographic Control Measures

The relationships between race, education, involvement in church, and change in God-mediated control were evaluated after the effects of age and sex were controlled statistically. Age is scored continuously in years, whereas sex (1 = men; 0 = women) is represented by a binary indicator.

Results

Assessing the Effects of Sample Attrition

As the discussion of the sampling procedures reveals, some older people who were interviewed for the baseline survey did not participate in the follow-up interview. The loss of subjects over time can bias study findings if it occurs in a nonrandom manner. The first set of analyses that were performed in this study was designed to evaluate the extent of this potential problem. Although it is difficult to determine if the loss of subjects has biased study findings, some preliminary insight can be obtained by seeing if select data from the Wave 1 survey are associated with study participation status at Wave 2. Evidence of bias would be found if any statistically significant relationships emerge from this analysis. The following procedures were used to implement this strategy. First, a variable consisting of three categories was created to represent older adults who remained in the study (scored 1), older people who were alive but did not participate at Wave 2 (e.g., those who refused to participate, scored 2), and older adults who had died (scored 3). Then, using multinomial logistic regression, this categorical measure was regressed on the following Wave 1 measures: age, sex, education, race, organizational religiousness, spiritual support, and God-mediated control. The category representing older people who remained in the study served as the reference group.

The findings (not shown here) reveal that none of the Wave 1 measures significantly differentiated between those who were alive but did not participate and those who remained in the study. However, the data further suggest that compared to those who remained in the study, respondents who had died were more likely to be older (b = 0.064; p < 0.001), to have fewer years of schooling (b = –0.085; p < 0.01), and were less likely to participate in formal church activities (b = –0.041; p < 0.05). In contrast, neither sex, race, spiritual support, nor God-mediated control significantly differentiated between respondents who had died and respondents who remained in the study. Even so, the potentially biasing influence of nonrandom sample attrition should be kept in mind as the substantive findings from this study are reviewed.

Substantive Findings

The model depicted in Figure 1 was assessed with the maximum likelihood estimator provided by Version 8.71 of the LISREL statistical software program (du Toit and du Toit 2001). However, use of this estimator rests on the assumption that the observed indicators in the model are distributed normally. Preliminary tests of the study measures (not shown here) revealed that this assumption had been violated. Although there are a number of ways to deal with departure from multivariate normality, the straightforward approach discussed by du Toit and du Toit is followed here. More specifically, these investigators report that departures from multivariate normality may be handled by converting raw scores on the observed indicators to normal scores prior to model estimation (du Toit and du Toit 2001:143). Based on this recommendation, the analyses presented below are performed with variables that have been normalized.

Fit of the Model to the Data

As discussed above, the data on God-mediated control were gathered at two points in time. As a result, two important issues must be addressed so that the model with the best fit to the data can be obtained. The first has to do with assessing factorial invariance over time, whereas the second deals with whether the measurement error terms in identical indicators of God-mediated control are correlated over time.

Because the same subjects were interviewed twice, it is important to see if the questions on God-mediated control mean the same thing to study participants at both points in time. One way to address this issue involves focusing on the stability of the elements of the measurement model over time (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms). If the meaning of study measures does not change over time, then study participants should answer the same questions in the same way. If they answer the same questions in the same way, then the covariances among these items should be the same at both points in time. And if this is true, then the factor loadings and measurement error terms that are derived from these covariances should be the same as well. But if the elements of the measurement model differ, there would be some evidence that the meaning of the items has changed over time. If this proves to be the case, it would be difficult to interpret the relationship between things like race and change in God-mediated control. This issue is known as the problem of factorial invariance over time (Bollen 1989).

Tests for factorial invariance over time are conducted in three steps. First, a baseline model (Model 1) is estimated in which all parameters in the measurement models of God-mediated control vary freely over time. Then, a model is estimated in which the factor loadings are constrained to be equivalent over time (Model 2). If this equality constraint does not change the fit of the model to the data significantly (as reflected in change in χ2 values), it is left in force when the third model is estimated. Model 3 tests for a higher order, more restrictive form of measurement equivalence. In particular, the measurement error terms associated with the indicators of God-mediated control are constrained to be equivalent over time. Once again, if this constraint does not change the fit of the model to the data significantly, it is left in place.

Following the tests for factorial invariance, the next step is to see if the measurement error terms associated with identical items assessing God-mediated control are correlated over time. Because God-mediated control is measured with the same questions at both points in time, it is possible that measurement error that arose at Wave 1 is correlated with measurement error in the same question when it was administered at Wave 2. The issue of autocorrelated error over time is tested with a final model (Model 4). If allowing the measurement error terms to correlate freely over time improves the fit of the model to the data, this constraint is left in place and efforts can be focused on the substantive relationships among the study constructs.

Tests were performed for all the models that were discussed above. The results of these tests are provided in Table 2. The findings reveal that the fit of the baseline model (Model 1) to the data is acceptable. More specifically, the Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI; Bentler and Bonett 1980) estimate of 0.974 is well above the recommended cut point of 0.900. Similarly, the standardized root mean square residual estimate of 0.030 is below the recommended ceiling of 0.050 (SRMR; Kelloway 1998). Finally, Bollen's (1989) Incremental Fit Index (IFI) value of 0.986 is quite close to the ideal target value for this index (i.e., 1.0).

TABLE 2.

GOODNESS-OF-FIT MEASURES FOR TESTS OF NESTED MODELS

| Model | χ 2 | df | χ2 change | Bentler-Bonett NFI | SRMR | Bollen IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 164.936 | 80 | ...... | 0.974 | 0.030 | 0.986 |

| 2 | 168.734 | 82 | 3.798 | 0.973 | 0.031 | 0.986 |

| 3 | 212.504 | 85 | 43.770*** | 0.966 | 0.033 | 0.980 |

| 4 | 162.265 | 79 | 6.469 | 0.974 | 0.031 | 0.987 |

p < 0.001.

NFI = Normed fit index (Bentler and Bonett 1980).

IFI = Incremental fit index (Bollen 1989).

SRMR = Standardized root mean square residual.

The first test of factorial invariance (see Model 2) indicates that constraining the factor loadings for the God-mediated control measures to be equivalent over time does not change the fit of the model to the data significantly. Evidence of this may be found by examining the change in χ2 values when Model 1 and Model 2 are compared (χ2 change 3.798 with 2 degrees of freedom is not statistically significant). This suggests that the factor = loadings are invariant over time and this equality constraint is left in place when Model 3 is tested.

The test of Model 3 reveals that the measurement error terms associated with the observed indicators of God-mediated control are not invariant over time. More specifically, the change in fit from Model 2 to Model 3 (χ2 change = 43.77 with 3 degrees of freedom) is significant at the 0.001 level. When viewed in conjunction with the test provided by Model 2, this suggests that the factor loadings are invariant over time, but the measurement error terms are not. Although it would have been better to find that all the elements in the measurement model are invariant, Reise, Widaman, and Pugh (1993) argue that achieving even partial invariance is acceptable, and that meaningful interpretations can be made when examining the effects of the independent variables on change in God-mediated control over time.

The final test (Model 4) involves seeing whether the error terms associated with identical items assessing God-mediated control are correlated over time. As the data in Table 2 reveal, the change in fit between Model 2 and Model 4 was not significant when the measurement error terms were allowed to be correlated over time (χ2 change = 6.469 with 3 degrees of freedom is not statistically significant). The tests conducted in this study suggest that the substantive findings reported below should be taken from Model 2. As the data in Table 2 reveal, the fit of this model to the data is good.

Psychometric Properties of the Observed Indicators

Table 3 contains the factor loadings and measurement error terms that were derived from Model 2. These coefficients are important because they provide preliminary information on the psychometric properties of the multiple-item study measures. Although no firm guidelines are provided in the literature, Kline (2005) suggests that standardized factor loadings in excess of 0.600 tend to have reasonable reliability. As the data in Table 3 reveal, the standardized factor loadings range from 0.589 to 0.914. Only two are below 0.600, and the differences between them and the target value are trivial. Therefore, the data in Table 3 suggest that the measures used in this study have good psychometric properties.

TABLE 3.

MEASUREMENT ERROR PARAMETER ESTIMATES FOR MULTIPLE-ITEM STUDY MEASURES (N = 661)

| Construct | Factor Loadinga | Measurement Errorb |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Organizational religiousness (Wave 1) | ||

| A. Church attendancec | 0.598 | 0.643 |

| B. Bible study groups | 0.805 | 0.352 |

| C. Prayer groups | 0.589 | 0.653 |

| 2. Spiritual support (Wave 1) | ||

| A. Someone shares religious experiences | 0.694 | 0.519 |

| B. Help you lead a better religious life | 0.836 | 0.301 |

| C. Help you to know God better | 0.852 | 0.275 |

| 3. God-mediated control (Wave 1)d | ||

| A. Rely on God to help control life | 0.784 | 0.385 |

| B. Succeed with God's help | 0.881 | 0.224 |

| C. Work together with God | 0.858 | 0.263 |

| 4. God-mediated control (Wave 2) | ||

| A. Rely on God to help control life | 0.867 | 0.248 |

| B. Succeed with God's help | 0.913 | 0.167 |

| C. Work together with God | 0.914 | 0.165 |

Factor loadings are from the completely standardized solution. The first-listed item for each latent construct was fixed at 1.0 in the unstandardized solution.

Measurement error terms are from the completely standardized solution. All factor loadings and measurement error terms are significant at the 0.001 level.

Item content is paraphrased for the purpose of identification. See Table 1 for the complete text of each indicator.

The second and third listed items were constrained to be equivalent in the unstandardized solution for the Wave 1 and Wave 2 measures of God-mediated control.

Although the factor loadings and measurement error terms associated with the observed indicators provide useful information about the reliability of each item, it would be helpful to know something about the reliability of the scales as a whole. Fortunately, these estimates can be derived with a formula provided by DeShon (1998). This formula uses the factor loadings and measurement error terms provided in Table 3. Although it is not discussed often in the literature, there is a problem with the way that reliability estimates are typically presented. As Vacha-Haagse et al. (2001) point out, the reliability of an instrument can never be assessed directly. Instead, data provided by a sample of respondents is used to obtain estimates of the reliability of a scale. However, because these data come from a sample, and not the entire population, reliability estimates will fluctuate from study to study. Consequently, it is important to derive confidence intervals for reliability estimates so that researchers can get a sense of where true population-based reliability coefficients are likely to fall. Fortunately, 90 percent confidence intervals (CI) for reliability estimates can be derived using the procedures described by Raykov (1998).

Applying the procedures described by DeShon (1998) and Raykov (1998) to the data in this study yields the following reliability estimates and confidence intervals for the composite measures in Figure 1: organizational religiousness (reliability = 0.707; lower CI = 0.706; upper CI = 0.779), spiritual support (reliability = 0.838; lower CI = 0.823; upper CI = 0.858), God-mediated control (Wave 1) (reliability = 0.880; lower CI = 0.861; upper CI = 0.889), and God-mediated control (Wave 2) (reliability = 0.926; lower CI = 0.915; upper CI = 0.933). As these estimates reveal, the reliability of the multiple-item constructs in this study is good.2

Substantive Findings

Table 4 contains estimates of the relationships among the latent constructs depicted in Figure 1. Consistent with the literature, the findings in Table 4 reveal that older whites tend to have more years of schooling than older African Americans (beta = 0.248; p < 0.001). In addition, as a number of studies have shown, the data indicate that older blacks are more likely to be involved in formal church activities than older whites (beta = –0.131; p < 0.01). However, the same is not true with respect to SES. More specifically, the findings suggest that the relationship between education and organizational religiousness is not statistically significant (beta = 0.078; n.s.). Taken together, these results reveal that race may play a greater role than SES in shaping levels of involvement in formal church activities in late life.

TABLE 4.

RACE, EDUCATION, RELIGIOUS INVOLVEMENT, AND GOD-MEDIATED CONTROL (N = 661)

| Dependent Variables |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Education | Organizational Religiousness | Spiritual Support | God-Mediated Control (Wave 1) | God-Mediated Control (Wave 2) |

| Age | –0.034a | –0.004 | –0.154*** | 0.012 | 0.002 |

| (–0.020)b | (–0.001) | (–0.017) | (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| Percent male | 0.013 | –0.135*** | 0.061 | –0.101** | –0.096** |

| (0.094) | (–0.257) | (0.085) | (–0.100) | (–0.104) | |

| Percent white | 0.248*** | –0.131** | –0.141*** | –0.113** | –0.115** |

| (1.700) | (–0.240) | (–0.189) | (–0.108) | (–0.120) | |

| Education | 0.078 | –0.046 | –0.083* | –0.015 | |

| (0.021) | (–0.009) | (–0.012) | (–0.002) | ||

| Organizational | 0.542*** | 0.185** | 0.088 | ||

| religiousness | (0.395) | (0.096) | (0.050) | ||

| Spiritual | 0.266*** | 0.213*** | |||

| support | (0.190) | (0.167) | |||

| God-mediated control | 0.197*** | ||||

| (Wave 1) | (0.216) | ||||

| Multiple R2 | 0.063 | 0.038 | 0.354 | 0.220 | 0.215 |

Standardized regression coefficient.

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

The findings in Table 4 further suggest that older people who are more involved in formal church activities tend to get more informal spiritual support from fellow church members than older people with lower levels of organizational religiousness (beta = 0.542; p < 0.001). The size of this relationship is fairly substantial by social and behavioral science standards.

The results in Table 4 indicate that both race and education are associated with God-mediated control at Wave 1. More specifically, the findings reveal that older whites are less likely than older blacks to believe it is important to work together with God to solve problems in life and reach desired goals (beta = –0.113; p < 0.01). The data also suggest that older adults with lower levels of educational attainment tend to have stronger baseline God-mediated control beliefs than older people with more years of schooling (beta = –0.083; p < 0.05). However, the size of this coefficient is fairly modest.

The findings in Table 4 further reveal that both organizational religiousness and informal spiritual support are associated with stronger God-mediated control beliefs at the baseline survey. More specifically, the data suggest that greater organizational religiousness is associated with greater God-mediated control (beta = 0.185; p < 0.01). In addition, more frequent spiritual support from fellow church members is associated with a stronger belief that working together with God will produce desired outcomes (beta = 0.266; p < 0.001). Visually comparing the magnitude of the coefficients for organizational religiousness and spiritual support appears to suggest that the effect of spiritual support is larger. Fortunately, this conclusion can be evaluated empirically by reestimating the model after the two coefficients have been constrained to be equivalent. The difference in χ2 values between Model 2 and this additional model tests whether the difference between the two estimates is statistically significant. The additional analyses suggest that the difference between the two estimates is not statistically significant (χ2 change = 2.034 with 1 degree of freedom is not significant). Therefore, the best conclusion is that both organizational religiousness and informal spiritual support influence baseline assessments of God-mediated control to the same degree.

A major contribution of the model depicted in Figure 1 arises from the fact that it is possible to estimate the relationship between key study constructs on feelings of God-mediated control over time. Four important findings involving these longitudinal data from the analyses are: first, the data suggest that compared to older African Americans, older whites are less likely to sustain feelings of God-mediated control over time (beta = –0.115; p < 0.01). Second, in contrast to the effects of race, SES does not appear to be significantly related to God-mediated control beliefs over time (beta = –0.015; n.s.). Third, the results indicate that greater involvement in formal church activities is not significantly associated with God-mediated control at the follow-up interview (beta = 0.088; n.s.). Finally, the data in Table 4 suggest that older people who receive more spiritual support from their fellow church members are more likely to maintain strong feelings of God-mediated control over the course of the study (beta = 0.213; p < 0.001).

The findings involving feelings of God-mediated control over time that have emerged up to this point may create the impression that informal spiritual support is a more important factor than involvement in formal church activities. However, this conclusion is not entirely correct because it is based on data that do not fully exploit the advantages afforded by latent variable models. As reported above, the direct effect of organizational religiousness on God-mediated control at the follow-up interview is not statistically significant. However, as the model in Figure 1 shows, this is not the only way that organizational religiousness may operate. In particular, the model further specifies that people who are more involved in formal church activities are more likely to get informal spiritual support from fellow church members, and greater spiritual support is, in turn, associated with strong God-mediated control beliefs at Wave 2. Stated in more technical terms, organizational religiousness may exert an indirect effect on follow-up values of God-mediated control that operates through spiritual support. So in addition to examining the direct effects of the constructs in Figure 1, it is also important to take their indirect effects into account. In fact, when the direct and indirect effects are combined, the resulting total effects provide a more comprehensive view of the relative impact of the key study constructs.

Table 5 contains the direct, indirect, and total effects that operate through the constructs depicted in Figure 1. The findings involving race, education, and organizational religiousness are especially important. As the data in Table 5 reveal, race exerts a statistically significant total effect on every construct in the model. More specifically, the data suggest that compared to older blacks, older whites are less likely to be involved in formal church activities (beta = –0.111; p < 0.05) and they are less likely to receive informal spiritual support from fellow church members (beta = –0.213; p < 0.001). In addition, older whites tend to have lower feelings of God-mediated control at Wave 1 (beta = –0.211; p < 0.001) and they are less likely to sustain strong feelings of God-mediated control over time (beta = –0.215; p < 0.001). Looking at the ratio between the indirect and total effects provides a convenient way of showing the proportion of the effects of race that is explained by the intervening constructs in the model. These data show that education, organizational religiousness, and spiritual support explain approximately 46 percent of the total effect of race on Wave 1 feelings of God-mediated control (i.e., –0.98/–0.211 = 0.464). Similarly, the constructs depicted in Figure 1 explain about 47 percent of the total effect of race on God-mediated control beliefs at Wave 2 (i.e., –0.100/–0.215 = 0.465).

TABLE 5.

DIRECT, INDIRECT, AND TOTAL EFFECTS

| Causal Effects |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable/Independent Variable | Direct (A) | Indirect (B) | Total (A+B) |

| Education/percent white | 0.248***a | ...... | 0.248*** |

| Organizational religiousness/percent white | –0.131** | 0.019 | –0.112* |

| Spiritual support/percent white | –0.141*** | –0.072** | –0.213*** |

| God-mediated control (Wave 1)/percent white | –0.113** | –0.098*** | –0.211*** |

| God-mediated control (Wave 2)/percent white | –0.115** | –0.100*** | –0.215*** |

| Organizational religiousness/education | 0.078 | ...... | 0.078 |

| Spiritual support/education | –0.046 | 0.042 | –0.004 |

| God-mediated control (Wave 1)/education | –0.083* | 0.014 | –0.069 |

| God-mediated control (Wave 2)/education | –0.015 | –0.008 | –0.023 |

| Spiritual support/organizational religiousness | 0.542*** | ...... | 0.542*** |

| God-mediated control (Wave 1)/organizational religiousness | 0.185** | 0.145*** | 0.330*** |

| God-mediated control (Wave 2)/organizational religiousness | 0.088 | 0.180*** | 0.268*** |

| God-mediated control (Wave 1)/spiritual support | 0.266*** | ...... | 0.266*** |

| God-mediated control (Wave 2)/spiritual support | 0.213*** | 0.052** | 0.265*** |

| God-mediated control (Wave 1)/God-mediated control (Wave 2) | 0.197*** | ...... | 0.197*** |

Standardized regression coefficient.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

In sharp contrast to the effects of race, the data in Table 5 indicate that none of the total effects of education on any of the constructs in Figure 1 are statistically significant. This suggests that when it comes to explaining how feelings of God-mediated control arise and are maintained over time, race appears to play a more significant role than education.

Supplementary Analyses

Earlier, based on the insights of Kessler and Greenberg (1981), it was reported that the relationship between formal involvement in the church, informal social relationships in the church, and God-mediated control at Wave 2 may mean that involvement in the church either sustains or increases feelings of God-mediated control over time. In addition, it was hypothesized that involvement in the church would sustain, rather than increase, an older person's sense of God-mediated control over time. But this hypothesis was based on theoretical considerations alone. It would be helpful if a preliminary empirical test of this hypothesis could be conducted as well. The purpose of this section is to describe a preliminary set of analyses that were designed to address this issue.

These analyses were conducted by creating an outcome variable consisting of three ordinal categories that designate three potential patterns of change or stability in God-mediated control over time. A score of 3 was assigned to older study participants whose feelings of God-mediated control increased over time (25.4 percent fell into this category), a score of 2 was given to older adults whose feelings of God-mediated control remained the same (43.8 percent), and a score of 1 was used to designate older respondents whose sense of God-mediated control declined between the Wave 1 and Wave 2 interviews (30.8 percent). Then, using multinomial logistic regression, this ordinal outcome measure was regressed on the Wave 1 measures of age, sex, education, race, organizational religiousness, and spiritual support. Older adults who experienced a decline in God-mediated control served as the reference category.

The findings (not shown here) revealed that compared to older people who experienced a decline in God-mediated control over time, older people who experienced an increase in God-mediated control were not more deeply involved in formal church activities (b = –0.018; n.s.; odds ratio = 0.983) nor were they more likely to receive informal spiritual support from fellow church members (b = 0.031; n.s.; odds ratio = 1.032). But, in contrast, the data further suggest that compared to older people who experienced a decline in feelings of God-mediated control, more spiritual support from fellow church members was significantly associated with having the same God-mediated control scores over time (b = 0.092; p < 0.05; odds ratio = 1.096). However, statistically significant findings failed to emerge with respect to organizational religiousness (b = 0.032; n.s.; odds ratio = 1.020). Taken as a whole, the supplementary analyses provide preliminary support for the notion that spiritual support from fellow church members sustains, but does not increase, feelings of God-mediated control over time.

Conclusion

The initiation of virtually any behavior is preceded by beliefs and expectations regarding the outcome of this conduct (Olson, Roese, and Zanna 1996). If people believe they can control the things that happen to them, then they are more likely to take an active problem-solving approach to life. But if individuals feel they are powerless in the face of the social forces that confront them, they will be less likely to initiate this type of coping behavior. Taking active steps to resolve problems and implement plans is important because doing so exerts a significant influence on health and well-being across the life course (Zarit, Pearlin, and Schaie 2002). Research on God-mediated control has contributed to this field by showing that this important facet of control also affects feelings of well-being in late life (Krause 2005). However, if feelings of God-mediated control affect well-being, then it is important to know how these control expectancies arise in the first place. This study examines this issue.

A conceptual model was developed for this study that traces the origins and maintenance of God-mediated control beliefs to the interplay between social structural factors (i.e., race and education) and formal as well as informal involvement in the church. The findings reveal that race, but not education, is an important correlate of God-mediated feelings of control in late life: older blacks have stronger feelings of God-mediated control than older whites at the baseline interview and older blacks are more likely to maintain strong feelings of God-mediated control over the course of the study. But instead of merely assessing the direct effect of race on God-mediated control, an effort was made to see if more frequent involvement in formal church activities and informal spiritual support from fellow church members help explain why race differences arise. The results indicate that nearly half the effect of race on God-mediated control is explained by the formal and informal ties that older African Americans maintain with the church. This is not a surprising finding. Writing in 1887, Du Bois (2000:21) clearly documented the pervasive role that the church played in the black community:

The Negro church . . . provides social intercourse, it provides amusement of various kinds, it serves as a newspaper and intelligence bureau, it supplants the theater, it directs the picnics and excursion, it furnishes the music, it introduces the stranger to the community, it serves as a lyceum, library, and lecture bureau (it is, in fine, the central organ of the organized life of the American Negro.

And insights provided by J. Deotis Roberts (2003:97), a noted black theologian, show how tightly knit black congregations can be an important force for bringing about social change through the exercise of collaborative control with God: “Thus, an awesome responsibility rests on Christians and churches . . . With God as our Helper, we can do much to alleviate pain and suffering.” However, it should be emphasized that the findings that emerged in the current study apply only to older people who attend church on at least a semi-regular basis (i.e., more than twice a year).

A good deal of work remains to be done because researchers are just beginning to understand the factors that influence feelings of God-mediated control. More research is needed in four key areas. First, Schieman et al. (2005) found complex interaction effects between factors like race, gender, divine control, and self-esteem. Perhaps the same complex factors bolster and maintain feelings of God-mediated control over time. For example, perhaps greater involvement in the church is more likely to bolster feelings of God-mediated control among older black women than either older men or older whites. Second, it would be important to see if feelings of God-mediated control are responsive to and shaped by stressful life events. For example, studies are needed to see if older people are more likely to turn to God for help with stressors that cannot be altered (e.g., death of a loved one). Moreover, it would be interesting to see if fellow church members play a role in this process by encouraging older people to rely on God-mediated control when significant stressors arise in their lives. Third, as noted earlier, older people may be more likely to have strong feelings of God-mediated control because they are more deeply involved in religion than younger adults, and because personal control over life as a whole tends to decline as people move through late life. However, this perspective was not evaluated empirically because data on younger people were not available in this study. Data from both younger and older adults are needed so researchers can see if God-mediated control provides a way of compensating for the loss of secular control in late life. In addition, research is needed to see if some older people get to the point where they no longer try to control their lives and, instead, turn things completely over to God (i.e., turn to divine control). In the process of conducting this research, it would be important to see if older people who have the greatest problems with physical and cognitive functioning are especially likely to turn control of their lives completely over to God. Fourth, more research is needed to flesh out the content domain of God-mediated control and differentiate this core construct from other facets of religion. For example, some of the items in this study (e.g., “All things are possible when I work together with God”) may be construed as measures of God-specific support. Additional research is needed to see if study participants differentiate between God-control and God-support and more work is needed to see if these constructs exert a differential impact on health and well-being.

In the process of exploring these issues, researchers should keep the limitations of this study in mind. Two are especially important. Even though the data were gathered at two points in time, thorny issues about the direction of causality nevertheless remain. The model that was estimated in this study was built on the assumption that spiritual support affects God-mediated control beliefs over time. But one might just as easily turn this logic around, and argue that people with an initially strong sense of God-mediated control are more likely to seek out and effectively use spiritual support from their fellow church members. Clearly, this issue cannot be conclusively resolved outside the context of studies that employ experimental designs.

Second, education was used in this study as the sole measure of SES. However, there are other, more sophisticated ways to measure SES, such as deriving measures of wealth. Perhaps different findings would have emerged in this study if factors such as wealth were used to measure SES.

Walker (2001:8) recently observed that “[t]he hypothesis that people are intrinsically motivated to achieve a sense of mastery over the environment is embedded in twentieth-century Western psychology.” Other investigators maintain that people have an intrinsic need for religion as well (see Kirkpatrick 2005 for a recent discussion of the controversy surrounding this claim). Taken together, these assertions suggest that feelings of God-mediated control may stand at the juncture of two key intrinsic needs. To the extent this is true, God-mediated control may be an especially powerful force in the lives of older people. Yet researchers know so little about it. Although research on God-mediated control is relatively new, it is hoped that the findings from this study spark further interest in it.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG014749).

Footnotes

As reported by Krause (2002a), the current study was preceded by an extensive series of qualitative interviews that were conducted in order to develop a comprehensive set of measures of religion. Although a number of constructs were explored during the course of this work, careful attention was given to the notion of God-mediated control. When subjects discussed this construct, many initially indicated that God controlled all the things that happened in their lives. This is consistent with the notion of divine control (Schieman et al. 2005). However, these study participants were subsequently asked if this meant that no action or involvement was, therefore, required on their part. A number of older study participants indicated this was not the case. Instead, they did all they could to resolve a problem or reach a goal and then turned to God for help after that. It is for this reason that the measures in the current study focus on collaborative control. However, given the initial response of subjects in the qualitative studies, responses to questions on divine control are likely to be correlated highly with responses to the items assessing God-mediated control in the current study.

The fact that the reliability estimates are especially high for God-mediated control helps explain why the measurement error terms for the observed indicators in these measures were not significantly correlated over time: because these indicators contain little measurement error, its not surprising to find that the Wave 1 and Wave 2 measurement error terms are not correlated significantly over time.

References

- Bandura A. Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In: Bandura A, editor. Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–600. [Google Scholar]

- Berrenberg JL. The belief in personal control scale: A measure of God-mediated and exaggerated control. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1987;51:194–206. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5102_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal S. Measuring income and inequality among the elderly. Gerontologist. 1986;26:56–59. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShon RP. A cautionary note on measurement error correlations in structural equation models. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:412–23. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois WEB. In: Du Bois on religion. Zuckerman P, editor. Altamira Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit M, du Toit S. Interactive LISREL: User's guide. Scientific Software International; Lincolnwood, IL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and further directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:700–20. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics . Older Americans 2004: Key indicators of well-being. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup G, Lindsay DM. Surveying the religious landscape: Trends in U.S. beliefs. Morehouse Publishing; Harrisburg, PA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- James W. The varieties of religious experience. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1985. [1902] [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Greenberg D. Linear panel analysis: Models of quantitative change. Academic Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Neighbors HW. A new perspective on the relationships among race, social class, and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1986;27:107–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick LA. Attachment, evolution, and the psychology of religion. Guilford; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002a;57B:S263–74. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.s263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring race differences in a comprehensive battery of church-based social support measures. Review of Religious Research. 2002b;44:126–49. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging. 2005;27:136–64. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Wulff KM. Church-based social ties, a sense of belonging in a congregation, and physical health status. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2005;15:73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Age differences in patterns and correlates of the frequency of prayer. Gerontologist. 1997;37:75–88. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindel CH, Vaughn E. A multidimensional approach to religiosity and disengagement. Journal of Gerontology. 1978;33:103–08. doi: 10.1093/geronj/33.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J. Age and sense of control. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1995;58:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education, social status, and health. Aldine De Gruyter; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olson JM, Roese NJ, Zanna MP. Expectancies. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. Guilford; New York: 1996. pp. 211–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56:519–43. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raykov T. A method for obtaining standard errors and confidence intervals of composite reliability for congeneric items. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1998;22:369–74. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Widaman KF, Pugh RH. Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:552–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JD. Black religion, black theology. Trinity Press International; Harrisburg, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Sastry J. The sense of personal control: Social-structural causes and emotional consequences. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Plenum; New York: 1999. pp. 369–94. [Google Scholar]

- Royce J. The sources of religious insight. Catholic University of America Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [1912] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Pudrovska T, Milkie MA. The sense of divine control and the self-concept. Research on Aging. 2005;27:165–96. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Heckhausen J. A life span model of successful aging. American Psychologist. 1996;51:702–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.51.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmel G. A contribution to the sociology of religion. In: Jurgen Helle H, editor. Essays on religion: Georg Simmel. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1997. pp. 101–20. [1898] [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Bainbridge WS. A theory of religion. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Finke R. Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin J. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vacha-Haagse T, Kogan LR, Tani CR, Woodall RA. Reliability generalization: Exploring variation of reliability coefficients of MMPI clinical scales scores. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. Control and the psychology of health. Open University Press; Philadelphia: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Welton GL, Adkins AG, Ingle SL, Dixon WA. God control: The fourth dimension. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1996;24:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow R. Sharing the journey: Support groups in America's new quest for community. Free Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Pearlin LI, Schaie KW. Personal control in social and life course contexts. Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]