Abstract

Prenyltransferases (PTSs) are involved in the biosynthesis of terpenes with diverse functions. Here, a novel PTS from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) is identified as a trans-type polyprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (AtPPPS), which forms a trans-double bond during each homoallylic substrate condensation, rather than a homomeric C10-geranyl pyrophosphate synthase as originally proposed. Biochemical and genetic complementation analyses indicate that AtPPPS synthesizes C25 to C45 medium/long-chain products. Its close relationship to other long-chain PTSs is also uncovered by phylogenetic analysis. A mutant of contiguous surface polar residues was produced by replacing four charged surface amino acids with alanines to facilitate the crystallization of the enzyme. The crystal structures of AtPPPS determined here in apo and ligand-bound forms further reveal an active-site cavity sufficient to accommodate the medium/long-chain products. The two monomers in each dimer adopt different conformations at the entrance of the active site depending on the binding of substrates. Taken together, these results suggest that AtPPPS is endowed with a unique functionality among the known PTSs.

Over 55,000 terpenes (isoprenoids), the largest class of plant metabolites, have been identified to be involved in numerous vital biological processes, including growth, development, and response to environment stresses (Fig. 1; Pichersky et al., 2006; Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007). Terpenes also have considerable applications as pharmaceuticals, fragrances, and nutritional supplements (Kirby and Keasling, 2009). These diverse compounds are derived from the rather simple universal precursors of linear prenyl pyrophosphates, ranging from C10 to C10,000 in the number of carbon atoms, which are synthesized by groups of conserved prenyltransferases (PTSs; Kellogg and Poulter, 1997; Liang et al., 2002). The various chain lengths of these linear prenyl pyrophosphates, reflecting their distinctive physiological functions (Fig. 1), in general are determined by the highly developed active site of PTSs via condensation reactions of allylic substrates (dimethylallyl diphosphate [C5-DMAPP], geranyl pyrophosphate [C10-GPP], farnesyl pyrophosphate [C15-FPP], geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate [C20-GGPP]) with corresponding number of isopentenyl pyrophosphates (C5-IPP; homoallylic substrate; Liang, 2009).

Figure 1.

Catalytic reactions and terpenoid biosynthesis. The schematic diagram shows the catalytic reactions of PTSs and outlines the terpenoid biosynthesis that leads to diverse products. The basic five-carbon building blocks of C5-IPP and its isomer, C5-DMAPP, are synthesized in vivo via the cytosolic mevalonate (MEV) pathway or the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway. The various chain lengths of linear prenyl pyrophosphates serving as the critical precursor for terpenoid biosynthesis are catalyzed by their respective PTSs. For C30- to C50-terpenes, the hydrophobic tail of quinine are derived from the long-chain linear prenyl pyrophosphates. The number of carbons in the prenyl tail differs from plastoquinone to ubiquinone and varies among the plant species. The abbreviation OPP indicates the pyrophosphate group.

PTSs are generally classified into cis- and trans-type enzymes on the basis of the stereochemistry of double-bound formation between the homoallylic substrate C5-IPP and the allylic substrates (Liang et al., 2002). In addition, the two types of PTSs not only differ completely in their primary amino acid sequences and tertiary structures but also utilize distinct mechanisms for substrate binding and catalysis, despite sharing the allylic and homoallylic substrates (Liang, 2009). The sequences of the trans-type PTSs generally have less than 30% conserved amino acids, although they possess a similar protein fold as well as two functional Asp-rich motifs, DD(X)nD (in which X encodes any amino acid and n = 2 or 4), reflecting the required diversity to achieve their specific condensation reactions (Kellogg and Poulter, 1997; Ogura and Koyama, 1998; Liang et al., 2002).

In plants, C10-GPP synthase (GPPS), which catalyzes the condensation of C5-DMAPP with C5-IPP into C10-GPP, is a key enzyme in the C10-monoterpene biosynthesis of plant volatiles to attract pollinators, mediators in interplant communication, and secondary metabolites for defense (Kessler and Baldwin, 2001; Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007). Intriguingly, enzymes possessing GPPS activity have been identified to be either homomeric or heteromeric proteins (Burke et al., 1999; Bouvier et al., 2000; Burke and Croteau, 2002; Tholl et al., 2004; Van Schie et al., 2007; Schmidt and Gershenzon, 2008; Orlova et al., 2009; Wang and Dixon, 2009; Schmidt et al., 2010), in contrast to most homomeric PTSs (Liang, 2009). We previously reported the structure of mint (Mentha piperita) heterotetrameric GPPS, composed of two active catalytic large subunits (LSU) and two regulatory noncatalytic small subunits (SSU; Chang et al., 2010), which is distinct from known homomeric PTSs such as C15-FPP synthase (FPPS) and C20-GGPP synthase (GGPPS; Chang et al., 2006; Kavanagh et al., 2006). The LSU is closely akin to the subunit of homomeric PTSs but lacks enzymatic activity on its own, and it requires the interactions with SSU to achieve a functional assembly (Kloer et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2010). The product fidelity of heterotetrameric GPPS is regulated via a regulatory loop in the SSU, which controls the product release from the catalytic LSU (Hsieh et al., 2010).

The homomeric Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) GPPS (AtGPPS) has been used as a model target for assessing the GPPS activity in angiosperms in the past decade (Bouvier et al., 2000; Lange and Ghassemian, 2003; Van Schie et al., 2007; Orlova et al., 2009). A recent study showed that Arabidopsis also expresses a heteromeric GPPS distinct from the homomeric type in their subunit compositions and sequence homology (Supplemental Fig. S1; Wang and Dixon, 2009). This discovery raises two questions. Why does Arabidopsis need to develop two separate types of GPPS? Does Arabidopsis benefit from possessing both types of enzymes? Furthermore, no structure of homomeric GPPS is available so far, and its enzymatic regulation mechanism is difficult to predict from the currently known structures of homomeric PTSs and heteromeric GPPS (Chang et al., 2006, 2010; Hsieh et al., 2010).

In an effort to address the above questions, the putative homomeric AtGPPS was cloned, expressed, and characterized by x-ray crystallography in combination with biochemical and genetic complementation analyses. Surprisingly, our results suggest that this enzyme from Arabidopsis is actually a polyprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (AtPPPS), an unusual PTS generating multiple products with medium/long chain length ranging from C25 to C45, rather than a GPPS as reported previously (Bouvier et al., 2000). Hence, we rename this homomeric AtGPPS to AtPPPS based on its enzymatic activity. These results should provide significant insights into the plant medium/long-chain PTSs and encourage further study to reevaluate the enzymatic functions and physiological roles of angiosperm GPPSs.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic Relationship

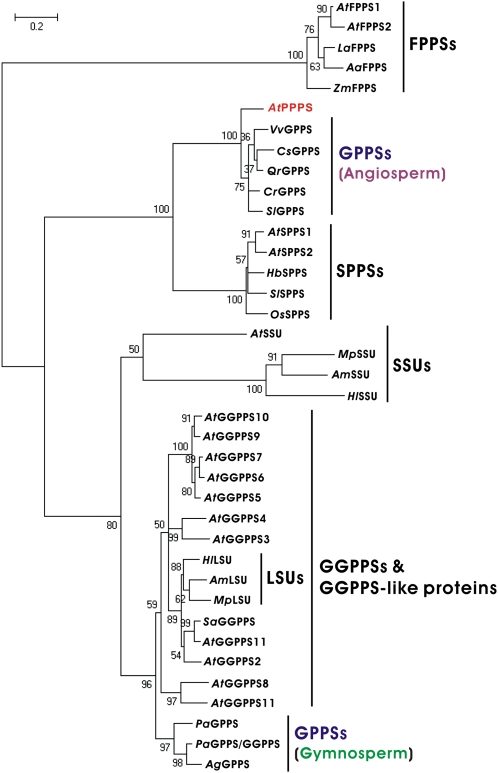

By sequence analyses, homomeric GPPSs in plants have been classified into two groups, one from gymnosperms and the other from angiosperms (Bouvier et al., 2000; Burke and Croteau, 2002; Van Schie et al., 2007; Schmidt and Gershenzon, 2008; Schmidt et al., 2010). AtPPPS has high identity, reaching about 70%, to other angiosperm homomeric GPPSs (Supplemental Fig. S2; Supplemental Table S1). However, detailed sequence alignment suggests that AtPPPS is actually similar to the long-chain PTSs (approximately 50% identity), which generate products beyond C35 (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S3; Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 2.

Structure-based multiple sequence alignment. The alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis PTSs includes PPPS (AtPPPS; AT2G34630), SPPS isoform 1 (AtSPPS1; AT1G78510), SPPS isoform 2 (AtSPPS2; AT1G17050), GGPPS isoform 1 (AtGGPPS1; AT1G49530), GGPPS isoform 11 (AtGGPPS11; AT4G36810), FPPS isoform 1 (AtFPPS1; AT5G47770), and FPPS isoform 2 (AtFPPS2;AT4G17190). Regions of AtPPPS corresponding to the α-helices are denoted by purple cylinders. Identical and similar amino acid residues are shaded in black and gray, respectively. Dashes indicate the sequence gaps introduced to optimize the amino acid sequence alignment. The conserved functional motifs, DD(X)nD, are boxed in cyan. The conserved residues surrounding the elongation cavity are boxed in green. The black triangle indicates the truncation site for AtPPPS expressed in E. coli as a pseudomature form by removing the plastid-targeting presequence. The mutation sites of SM-AtPPPS and AtPPPS(I99F/V162F) are marked by green stars and red dots, respectively. All sequences presented here have the N-terminal signal peptides omitted.

To resolve this controversy, we further analyzed the phylogenetic relationships between AtPPPS and other plant PTSs (Fig. 3). The phylogenetic tree shows that AtPPPS is evolutionarily more closely related to the long-chain PTSs (e.g. C45-solanesyl pyrophosphate synthase [SPPS] and C50-decaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase) than to the short-chain PTSs (e.g. GGPPS and FPPS). An exception, naturally, is the grouping with other angiosperm GPPSs. Previous studies suggest that the active site of PTSs has been exquisitely developed to control their substrate and product specificities (Ohnuma et al., 1996; Tarshis et al., 1996; Guo et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006). Therefore, the specifically conserved amino acid sequence of PTSs has been used to predict the chain length of the final product (Kellogg and Poulter, 1997; Ogura and Koyama, 1998; Liang, 2009). Our results imply that AtPPPS and long-chain PTSs may have similar functions.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of amino acid sequences of plant PTSs. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the MEGA4 package (Tamura et al., 2007). The branch lengths of the lines indicate the evolution distances, and numbers reveal the tree confidence calculated by bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates. The abbreviations and accession numbers are detailed in “Materials and Methods.”

Catalytic Activity

To investigate the genuine enzymatic function of AtPPPS, we expressed and purified the protein in a pseudomature form by removing the plastid targeting sequence (Supplemental Table S2). Its activity was subsequently measured using four allylic substrates (C5-DMAPP, C10-GPP, C15-FPP, and C20-GGPP) in the presence of C5-[14C]IPP. Surprisingly, the reaction yielded a broad spectrum of multiple products ranging from C25 to C45 (Fig. 4). Except for C5-DMAPP, AtPPPS can recognize the other three allylic substrates and react them with C5-[14C]IPP, resulting in similar multiple product distribution patterns having C35 as the major product (Fig. 4; Table I). In the subsequent time-course assay, multiple products were detected simultaneously (i.e. not sequentially) in the chain elongation process (Supplemental Fig. S4). This observation further indicates that the products of medium/long chain lengths as synthesized by AtPPPS (Fig. 4) are not a result of the longer reaction time. Additionally, our results also imply that the released products having longer chain lengths than C25 would have a lower frequency of rebinding to the active site for further product elongation. Based on its product distribution, we rename this enzyme as a PPPS. Intriguingly, most PTSs are monofunctional enzymes that exclusively synthesize single chain-length products (Tarshis et al., 1996; Ogura and Koyama, 1998; Guo et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006), whereas a few PTSs from Cryptosporidium parvum, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, Myzus persicae, Picea abies, Toxoplasma godii, and Zea mays also possess the catalytic promiscuity to produce more than one product (Chen and Poulter, 1993; Cervantes-Cervantes et al., 2006; Ling et al., 2007; Artz et al., 2008; Vandermoten et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2010).

Figure 4.

Biochemical assays of product synthesis by WT-AtPPPS. The experiments were carried out in the presence of various allylic substrates with C5-[14C]IPP. The products of Sulfolobus solfataricus C30-HPP synthase (SsHPPS) and Thermotoga maritima octaprenyl pyrophosphate (C40-OPP) synthase (TmOPPS), synthesizing C30-HPP and C40-OPP, were used as markers (Guo et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005). The product distributions are summarized in Table I.

Table I. Product distributions of WT-AtPPPS, SM-AtPPPS, and AtPPPS(I99F/V162F) in the presence of a range of allylic substrates.

The radioactivity of each product was normalized by the numbers of C5-[14C]IPP incorporated. Further experimental details can be found in “Materials and Methods.”

| Allylic Substrates | Products |

|||||

| C20 | C25 | C30 | C35 | C40 | C45 | |

| % | ||||||

| WT-AtPPPS | ||||||

| C5-DMAPP | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C10-GPP | – | 7.6 | 19.3 | 54.7 | 13.9 | 4.5 |

| C15-FPP | – | 14.8 | 30.1 | 40.4 | 11.1 | 3.6 |

| C20-GGPP | – | 12.2 | 22.8 | 44.8 | 14.3 | 5.7 |

| SM-AtPPPS | ||||||

| C5-DMAPP | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C10-GPP | – | 5.1 | 19.2 | 53.8 | 16.4 | 5.5 |

| C15-FPP | – | 16.3 | 32.2 | 38.6 | 10.2 | 2.6 |

| C20-GGPP | – | 13.9 | 21.7 | 44.6 | 15.1 | 4.7 |

| AtPPPS(I99F/V162F) | ||||||

| C5-DMAPP | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C10-GPP | 87.3 | 12.7 | – | – | – | – |

| C15-FPP | 92.2 | 7.5 | 0.4 | – | – | – |

| C20-GGPP | – | 94.2 | 5.8 | – | – | – |

Overall Structure and Active Site

To further understand its function, we determined the crystal structure at 2.6-Å resolution of the wild-type AtPPPS in its apo form, denoted WT-AtPPPS (Fig. 5A; Table II). While WT-AtPPPS shares less than 30% sequence identity with other PTSs, it clearly adopts the conserved all-α-helix fold of PTSs (Tarshis et al., 1996; Liang, 2009). A stable homodimer was also detected by gel filtration analysis in a protein concentration-independent manner (Supplemental Fig. S5), consistent with previous findings that most PTSs exist as homodimers under physiological conditions (Guo et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006; Kloer et al., 2006; Hsiao et al., 2008). The dimerization interface is mainly contributed by the respective helices F and G (Fig. 5A). Each subunit is composed of 16 antiparallel α-helices that surround the active site, with the two conserved DD(X)nD motifs facing each other on helices D and J (Fig. 5A). The electron density maps of a few loop regions (residues 1–7, 35–46, 68–81, and 110–125 for chain A; residues 1–8, 35–46, 68–81, and 111–125 for chain B) were not clearly visible (Fig. 5A). The active-site region of WT-AtPPPS is embedded with highly conserved catalytic amino acid residues to be implemented in its enzymatic reaction. The consensus catalytic mechanism of PTSs has been demonstrated to be a set of sequential ionization-condensation-elimination reactions: the homoallylic substrate attacks the allylic substrate, which forms a carbocation intermediate by removing its inorganic pyrophosphate group, with concomitant removal of a proton from the adduct (Liang et al., 2002; Liang, 2009). The binding of the allylic substrate is mainly contributed by the DD(X)nD motifs, Mg2+ ions, and the associated water molecules. The homoallylic substrate is bound in a positively charged pocket surrounded by residues Arg-54, His-100, and Arg-117.

Figure 5.

Overall structure of AtPPPS. A, Representation of the apo form dimeric WT-AtPPPS. Disordered regions are indicated by red and blue dashed lines for the monomers colored in rainbow (chain A) and gray (chain B), respectively. The conserved DD(X)nD motifs are shown as sticks in magenta. B, Ternary complex of SM-AtPPPS with bound Mg2+ ions, C5-IPSP, C15-FPP, and inorganic pyrophosphate groups. The octamer comprises an asymmetric unit. Monomers belonging to the same dimer are colored similarly. The squares and circles associated with chain names denote two different subunit conformations. C, The ligand-bound monomer structure of SM-AtPPPS. The disordered region is indicated by a black dashed line. The electron density maps of Mg2+ ions, C5-IPSP, and C15-FPP (2|Fo|−|Fc| map) are contoured at 1.0 σ level as green meshes.

Table II. Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Statistics | Apo Form (WT-AtPPPS) | Ternary Complex (SM-AtPPPS) |

| Ligands | – | Mg2+/C5-IPSP/C15-FPP |

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | F222 | P61 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | ||

| a | 148.51 | 115.96 |

| b | 150.13 | 115.96 |

| c | 176.11 | 385.87 |

| Resolution (Å)a | 30.00-2.60 (2.69-2.60) | 30.00-2.65 (2.74-2.65) |

| No. of unique reflectionsa | 30,232 (2,979) | 83,662 (8,206) |

| Redundancya | 3.9 (3.5) | 3.7 (2.6) |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.5 (98.8) | 98.8 (97.4) |

| Average I/σ(I)a | 18.3 (2.5) | 28.3 (2.1) |

| Rmerge (%)ab | 7.1 (48.9) | 4.8 (49.5) |

| Refinement | ||

| No. of reflectionsc | 28,230 | 79,172 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%)de | 20.6/25.6 | 22.2/27.4 |

| r.m.s. deviationsf | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 | 0.011 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.685 | 1.472 |

| B value (Å2)/no. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 48.0/4,586 | 32.2/19,484 |

| Ligand/ion | – | 47.9/248 |

| Water | 53.5/373 | 47.8/721 |

| Ramachandran plot (%)g | ||

| Most favored regions | 93.1 | 92.8 |

| Allowed regions | 6.5 | 6.4 |

| Generously allowed | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Disallowed | 0 | 0.1 |

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution data shell.

Rmerge = ∑∑I(h)j − <I(h)>/∑∑I(h)j, where I(h)j is the measured diffraction intensity and the summation includes all observations.

All positive reflections were used in the refinement.

Rwork is the R factor = (∑|Fo| − ∑|Fc|)/∑|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Rfree is the R factor calculated using 5% of the data that were excluded from the refinement.

The r.m.s. deviation is the root mean square deviation from ideal geometry of protein.

Ramachandran plots were generated with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993). For the ternary complex of SM-AtPPPS, three residues, Asn-123 (chain D), Leu-30 (chain D), and Leu-30 (chain F), are located in the disallowed region.

To further unveil details in the product elongation region of AtPPPS, we sought to solve the structure of WT-AtPPPS in complex with its ligand. Despite extensive efforts, WT-AtPPPS failed to crystallize in a ligand-bound form. Crystallization is generally believed to involve the free energy change upon assembly of the protein molecules into a crystal lattice. Hence, replacing high-entropy polar amino acids on the protein surface with Ala residues has been used to reduce the entropy, in favor of crystal contact formation (Derewenda, 2004; Goldschmidt et al., 2007). To enhance the crystallizability of AtPPPS, we used the Surface Entropy Reduction prediction server (http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/SER/) to analyze the primary sequence and located several flexible polar resides with high entropy values. We then constructed several mutants according to the prediction and finally obtained a mutant of contiguous surface polar residues, denoted SM-AtPPPS, by replacing four residues (Glu-178, Gln-179, Glu-281, and Lys-282; Fig. 2) on the protein surface with Ala residues to facilitate crystal lattice formation. Although the mutations reduced the enzymatic activity slightly when C10-GPP was used as the allylic substrate, the overall functional activity and product distribution pattern of SM-AtPPPS remained comparable with those of WT-AtPPPS (Supplemental Fig. S6; Table I).

The SM-AtPPPS crystal solved at 2.65-Å resolution contains an octamer (chain A–H) as its asymmetric unit, comprising four identical dimers related by three orthogonal noncrystallographic 2-fold axes and expressing a tetrahedral 222 symmetry (Fig. 5B; Table II). Those four mutations generate additional intermolecular crystal contacts both within the asymmetric unit and between different octamers in the unit cell (Supplemental Fig. S7). Although the two monomers in each dimer adopt distinct conformations, a dimer as the basic assembly unit is consistent with WT-AtPPPS and other known structures of PTSs (Tarshis et al., 1996; Guo et al., 2004; Hosfield et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006; Kavanagh et al., 2006; Kloer et al., 2006). Judging by its gel filtration chromatography profile, SM-AtPPPS also exists as a dimer in solution (data not shown). The electron density map clearly shows that a different monomer is bound with either Mg2+ ions, an inactive C5-IPP analog isopentenyl thiolopyrophosphate (C5-IPSP), and C15-FPP or Mg2+ ions, inorganic pyrophosphate, and C15-FPP in its active site (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. S8). The crystal structure of homodimeric Sinapis alba GGPPS was found to contain different ligands bound to different subunits as well (Kloer et al., 2006). The N-terminal residues and some surface loops were disordered.

Further structural analyses show that the aliphatic tail of C15-FPP is located in a large hydrophobic cleft starting with the active site cavity and connecting with the elongation cavity (EC) adjacent to the dimer interface (Fig. 6A). Previous studies suggest that the regulation of product chain length specificity and substrate selectivity is determined by the size of the tunnel-shaped cleft of PTSs, since the product elongation extends along the EC tunnel (Ohnuma et al., 1996; Tarshis et al., 1996; Guo et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006). The bound substrate models and the critical amino acid residues in the active site of AtPPPS are similar to those of all other known PTSs, as verified by the biochemical and crystallographic studies (Liang et al., 2002; Liang, 2009). The residues located on helices D, E, and G that surround the EC tunnel are highly conserved among long-chain PTSs (Fig. 2).

Figure 6.

Determination of product specificity. A, Surface representations of the active-site region in SM-AtPPPS. The residues Ile-99 and Val-162 are highlighted in yellow. The C15-FPP (magenta) and C5-IPSP (blue) ligands are represented as sticks and Mg2+ ions are represented as green balls. Green and orange dotted circles denote the EC and the active-site cavity (AC), respectively. The purple arrow indicates a hole for product elongation beyond C20- or C25-prenyl pyrophosphate intermediates. The blue dashed arrow denotes the possible product elongation pathway. B, In vitro analysis of product distributions of the mutant AtPPPS(I99F/V62F). C, Schematic diagram for the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway, beginning with a coupled reaction of two C20-GGPP molecules and the construct pACCAR25ΔcrtE. D, Genetic complementation assay for detecting yellow pigment production in E. coli harboring pACCAR25ΔcrtE and the expression vectors.

Overall, these structural studies of AtPPPS allow an unambiguous identification of a cavity to accommodate longer products beyond C10-GPP (Figs. 5C and 6A; Supplemental Fig. S8).

Comparison of the apo Form and the Ternary Complex

Superposition of WT-AtPPPS and SM-AtPPPS allows the identification of three notable regions with significant conformational changes (Supplemental Fig. S9). First, the disordered region of helices D to F shows ligand-binding-induced conformational changes to act as a gate for substrate entry and product release, consistent with previous studies (Sun et al., 2005; Kloer et al., 2006). Second, the region connecting helices A and C has extensive conformational change. Helix B becomes an ordered structure when the C5-IPP substrate is bound (Supplemental Fig. S9). Therefore, this highly mobile region may be induced to become ordered by the binding of C5-IPP. Third, the orientation of the first N-terminal helix A protrudes into the top of the other subunit and seems to be involved in regulating the conformational change during the catalytic reaction (Supplemental Figs. S8 and S9). This is in accordance with an alternating catalytic mechanism in the dimer (i.e. when one subunit is in action, the other subunit is empty in its active site; Sun et al., 2005; Kloer et al., 2006). The alternating mechanism is also reflected in the asymmetric binding of different ligands to different protein subunits of the homodimeric enzyme. This kind of enzymatic regulation mechanism may be used to control the steps of substrate entry and product release. Hence, these observations of the crystal structure further explain why the basic functional unit of PTSs is a dimer instead of a monomer.

The Mechanism of Product Elongation

To investigate how the EC tunnel accommodates the long-chain products, two hydrophobic residues, Ile-99 on helix D and Val-162 on helix G, in the middle of the EC tunnel are substituted by larger Phe residues to serve as a new floor to block the product chain elongation beyond C20-GGPP (Fig. 6A). AtPPPS(I99F/V162F) generates C20-GGPP as the major product, plus a small amount of farnesylgeranyl pyrophosphate (C25-FGPP; Fig. 6B; Table I). The shorter product chain length is consistent with the reduced size of the EC tunnel as a result of the mutations. As expected, the mutant enzyme showed lower activity to recognize the C20-GGPP as the allylic substrate to implement the chain-elongation reaction, while the activity for C15-FPP was largely unaffected (Fig. 6B). The altered active-site structure might have an unfavorable effect in retaining the short-chain intermediate; therefore, the enzymatic activity for reacting C10-GPP with C5-IPP was reduced.

Although C20-GGPP from the AtPPPS(I99F/V162F) mutant can be detected by in vitro assay, it remains to be validated under in vivo conditions. The genetic complementation method (Zhu et al., 1997; Engprasert et al., 2004; Chang et al., 2010) was employed to investigate whether this mutant exhibits the GGPPS activity in vivo. The crt gene cluster of Pantoea ananatis, responsible for biosynthesis of the yellow pigment carotenoid except crtE, which encodes GGPPS, was constructed into pACCAR25ΔcrtE (Fig. 6C; Zhu et al., 1997). Escherichia coli does not possess an intrinsic GGPPS gene; therefore, the E. coli cells carrying the pACCAR25ΔcrtE vector and the empty vector pET-16 cannot accumulate the yellow pigment (Fig. 6D). In contrast, transformants harboring pACCAR25ΔcrtE and pET-32 that contains the Saccharomyces cerevisiae GGPPS or AtPPPS(I99F/V162F) gene showed a visible yellow color, and the extracted pigments were further measured by optical absorption (Fig. 6D; Supplemental Fig. S10). Taken together, these results confirm that the double mutant produces C20-GGPP as the major product both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 6, B and D).

DISCUSSION

The plant GPPS-encoding genes have been identified in both gymnosperms and angiosperms (Burke et al., 1999; Bouvier et al., 2000; Burke and Croteau, 2002; Tholl et al., 2004; Van Schie et al., 2007; Schmidt and Gershenzon, 2008; Wang and Dixon, 2009; Schmidt et al., 2010). Interestingly, enzymes exhibiting this catalytic activity can be further classified into homomeric and heteromeric proteins. In contrast to the studies of homomeric proteins (Chang et al., 2006; Liang, 2009), the crystal structure of a heteromeric GPPS and its enzymatic regulation mechanism were elucidated very recently (Chang et al., 2010; Hsieh et al., 2010). The production of C10-GPP is the key branching point in the C10-monoterpene biosynthesis by which the plant volatiles with the critical bioactivities involved in plant growth, development, and defense are made (Pichersky et al., 2006; Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007).

The model plant Arabidopsis is generally believed to be a self-pollinating plant. However, several pieces of evidence support that insect-mediated cross-pollination also happens in the wild population (Jones, 1971; Snape and Lawrence, 1971; Davis et al., 1998). Arabidopsis has been confirmed to synthesize plant volatiles and emits a range of these compounds from its flower (Aharoni et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2003). Remarkably, the emission of volatiles is a major feature of most insect-pollinated flowers (Dudareva and Pichersky, 2000). In addition, the C10-monoterpene could also protect the reproductive organs from pathogen attack or oxidative damage (Wu et al., 2006). Consequently, the presence of homomeric GPPS in Arabidopsis can be responsible for providing the C10-GPP in the critical metabolism of C10-monoterpenes. On the other hand, Wang and Dixon (2009) have also identified a new plastidic Arabidopsis heteromeric GPPS, comprising SSU (AtSSU) and GGPPS isoform 11 (AtGGPPS11).

Here, we showed that the homomeric GPPS in Arabidopsis should be a novel enzyme to generate multiple products with medium/long chain lengths, rather than a GPPS as reported previously (Bouvier et al., 2000). The previous study used C5-DMAPP and C5-[14C]IPP in a ratio of 2:1. A homolog from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) was also proposed to possess the GPPS activity when the ratio of C5-DMAPP to C5-[14C]IPP was 2.5:1 (Van Schie et al., 2007). In contrast, we used various ratios of 1:15, 1:14, 1:13, and 1:12 for C5-DMAPP to C5-[14C]IPP, C10-GPP to C5-[14C]IPP, C15-FPP to C5-[14C]IPP, and C20-GGPP to C5-[14C]IPP, respectively, to ensure sufficient homoallylic substrates (C5-IPP) for the condensation reaction (see “Materials and Methods”) and determined the preferred allylic substrate of AtPPPS. Even in this assay condition, two unexpected products of C15-FPP and C20-GGPP were detected by using radio-gas chromatography (Van Schie et al., 2007). Hence, if sufficient C5-[14C]IPP is provided for the continued enzymatic reaction, the short-chain products would turn out to become the medium/long-chain products.

Although AtPPPS showed some GPPS activity when the isotope signal was measured prior to performing thin-layer chromatography, it was barely detectable and insignificant. By reacting C5-[14C]IPP with the other three allylic substrates (C10-GPP, C15-FPP, and C20-GGPP), similar multiple medium/long-chain product distribution patterns were observed (Fig. 4). It is also consistent with our phylogenetic analysis that AtPPPS is closely related to long-chain PTSs and with the previous studies that the long-chain PTSs generally prefer using C15-FPP as the allylic substrate instead of C5-DMAPP (Kellogg and Poulter, 1997; Ogura and Koyama, 1998; Liang et al., 2002). The long-chain PTSs possess a long hydrophobic tunnel, which has higher affinity for intermediates with a longer aliphatic tail. Because C5-DMAPP has the shortest tail, it would be harder for C5-DMAPP to remain in the long hydrophobic tunnel and easier to escape from the active site into the bulk solvent than the other allylic substrates. The subtle balance between substrate binding and product release seems to determine the product chain length distribution.

Moreover, the crystal structures of AtPPPS, in its apo and ligand-bound forms, indicate that its substrate-binding cleft is capable of accommodating products larger than C10-GPP. The two point mutations of AtPPPS(I99F/V162F) in the cleft lead to the short-chain-length product of C20-GGPP, with consistent results both in vitro and in vivo. Our results not only clarify the originally thought homomeric GPPS to be AtPPPS but also help explain the actual role of Arabidopsis heteromeric GPPS in the process of C10-monoterpene biosynthesis.

Nevertheless, two other questions remain to be investigated. First, does the regulation system of heteromeric GPPS in Arabidopsis act like other plant heteromeric GPPSs to modulate the distribution of C10-GPP and C20-GGPPS and display the tissue-specific expression pattern (Tholl et al., 2004; Orlova et al., 2009; Wang and Dixon, 2009)? Second, what is the exact biological role of AtPPPS in plants? As shown in previous studies of cellular compartments (Bouvier et al., 2000), AtPPPS has been identified to be capable of transporting into nongreen plastids and chloroplast photosynthetic cells. Additionally, plant SPPSs, closely related to AtPPPS by our phylogenetic analysis, are generally considered to be employed in generating the long-chain prenyl products to serve as the terpene side chains of ubiquinone and plastoquinone, essential components of the electron transport machinery (Hirooka et al., 2003; Jun et al., 2004). Soll et al. (1985) also reported that the final steps of plastoquinone biosynthesis are implemented on the inner envelope of chloroplasts. Judging by these findings, it is tempting to suggest that AtPPPS may play a role in Arabidopsis ubiquinone and plastoquinone biosynthesis. However, we cannot exclude that AtPPPS may also function in other terpene biosyntheses, such as gibberellin, carotenoid, and chlorophyll. It is thus an open question regarding the physiological roles of such multiple medium/long-chain products generated by AtPPPS. It remains to be investigated whether these multiple products can serve as precursor pools to precisely balance diterpene, triterpene, tetraterpene, and polyterpene metabolisms, because the dysfunction in the terpene biosynthesis has been reported to have a deleterious effect on plant growth and development (Orlova et al., 2009). We also survey sequences similar to AtPPPS by using the conventional sequence homology search to provide insight for future investigations (Supplemental Table S3). In the end, the role played by AtPPPS remains to be clarified, and our findings encourage reevaluating its enzymatic function in the complex system of metabolite biosyntheses.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, the crystal structures of AtPPPS in combination with phylogenetic analysis and both in vitro and in vivo biochemical assays have clarified the role of this enzyme, which was thought to be a GPPS in previous studies (Bouvier et al., 2000), to be an unusual PTS that synthesizes multiple medium/long-chain products. Our results, along with the identification of a heteromeric GPPS from Arabidopsis (Wang and Dixon, 2009), suggest that the precursor C10-GPP for C10-monoterpene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis may be provided only by heteromeric GPPS. The integrated approach as described here can also be a good example of how gene functions in plant terpene biosynthesis are unraveled.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and Mutagenesis

The sequence information of AtPPPS was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information data library with the accession number AT2G34630. The PCR product without its plastid-targeting sequences was amplified by PCR from the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) cDNA libraries using the primers LIC-TEV-At-F and LIC-At-R and cloned into pET-32 Xa/LIC (Novagen; Supplemental Table S2). The forward primer LIC-TEV-At-F includes a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site allowing for N-terminal fusion tag removal. To enhance the nickel-resin-binding affinity, the vector WT-AtPPPS/pET-32 was constructed to insert one additional His6 tag by site-directed mutagenesis. The TEV protease was cloned into pET-51 Ek/LIC (Novagen) by using primers of LIC-TEV-F and LIC-TEV-R (Supplemental Table S2). Other mutant constructs, SM-AtPPPS/pET-32 and AtPPPS(I99F/V62F)/pET-32, used WT-AtPPPS/pET-32 as template and were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis. The primers are shown in Supplemental Table S2.

Protein Expression and Purification

WT-AtPPPS/pET-32 was transformed to Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) (Novagen) and induced with 0.1 mm isopropyl β-thiogalactopyranoside in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg mL−1 carbenicillin at 10°C for 24 h. Cell pellets were harvested and resuspended in extraction buffer [50 mm Tris, pH 8.5, 40 mm imidazole, 0.75 m NaCl, 25% (w/v) glycerol, 0.2 m sorbitol, 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), 2 ng mL−1 benzonase (Novagen), and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche)]. Cell lysate was prepared by Cell Disruption Solutions (Constant Systems) and centrifuged at 38,000 rpm (Beckman Ti45) for 60 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. After filtration by using Stericup (Millipore), the supernatant was loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated with extraction buffer. The column was washed with wash buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 20 mm imidazole, 0.5 m NaCl, 10% [w/v] glycerol, 10 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm TCEP) following 10% (v/v) elute buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 250 mm imidazole, 0.5 m NaCl, 10% [w/v] glycerol, 10 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm TCEP) and eluted with a linear gradient to 100% (v/v) elute buffer. The isolated sample was dialyzed twice against 5 L of buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.5, 10% [w/v] glycerol, and 2 mm dithiothreitol) and then incubated with TEV protease, purified as described previously (Lucast et al., 2001). The digested sample was loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column linked with an ion-exchange column (Hitrap Q HP; GE Healthcare) preequilibrated with balance buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 8.5, 5% [w/v] glycerol, and 2 mm TCEP) and eluted using a 50 to 500 mm NaCl gradient. The homodimeric protein was further purified twice by using gel filtration (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 and HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75; GE Healthcare) in 25 mm Tris, pH 8.5, 5% (w/v) glycerol, and 2 mm TCEP. Purification of the AtPPPS mutants followed similar procedures. The recombinant proteins TmOPPS, SsHPPS, and ScGGPPS(H139A), which served as the standard in the biochemical assay, were expressed and purified as described previously (Guo et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006). The molecular assembly of AtPPPS in solution was further determined on an analytic gel filtration column (Superdex 200 10/300 GL High Performance; GE Healthcare) by comparing with those protein molecular mass standards (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

Crystals of WT-AtPPPS were grown in hanging drops by the vapor diffusion method at 20°C for 3 months in a mixture of 2 μL of protein solution (4 mg mL−1; 25 mm Tris, pH 8.5, 5% [w/v] glycerol, and 2 mm TCEP), 2 μL of reservoir solution (60% [v/v] Tacsimate, pH 7.0), and 0.5 μL of Silver Bullets (Hampton Research). At a higher concentration, the protein tended to aggregate and form clustered crystals. Notably, during such a long spell of crystal growth, no protein degradation or other defect was found in the process of data collection and structure determination of WT-AtPPPS. The crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant (reservoir solution and 20% [v/v] Suc) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to data collection. For cocrystallization by the vapor diffusion method, the SM-AtPPPS crystals were obtained by mixing 2 μL of protein solution (4 mg mL−1; 25 mm Tris, pH 8.5, 5% [w/v] glycerol, and 2 mm TCEP) in the presence of 1.25 mm ligands (MgCl2, C15-FPP, and C5-IPSP) with 2 μL of reservoir solution (18% [w/v] polyethylene glycol 3350, 0.17 m sodium thiocyanate, pH 6.0) at 20°C for 3 weeks. The crystallization drop was stepwise supplemented with 10% (v/v) polyethylene glycol 200 and then covered with perfluoropolyether PFO-X175/08 (Hampton Research) before flash cooling to 100 K in a stream of cold nitrogen. Diffraction data for WT-AtPPPS and SM-AtPPPS were collected at the Taiwan Contract BL12B2 Station at Spring-8 (Hyogo, Japan) and the beamline 5A at the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). Data were processed and scaled by using the HKL2000 package (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Five percent randomly selected diffraction data were used for calculating Rfree (Brünger, 1993).

The structure of WT-AtPPPS was determined by molecular replacement with MOLREP (Lebedev et al., 2008). The most possible molecular replacement template of GGPPS (Protein Data Bank accession code 1WYO) from Pyrococcus horikoshii Ot3 was searched using MrBUMP (Keegan and Winn, 2008) and further modified by Chainsaw (Schwarzenbacher et al., 2004) to remove unaligned residues and truncate the side chain of nonconserved residues to the γ-position based on sequence alignment. The model was rebuilt into an electron density map using Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004), and the phases derived from the resulting model were subject to automatic model building in Buccaneer (Cowtan, 2006). The octameric SM-AtPPPS was solved by using the monomer of WT-AtPPPS as a search model. The first four molecules in the asymmetric unit were found with PHASER (McCoy, 2007), and the other four molecules were further placed with MOLREP (Lebedev et al., 2008) after the first four molecules were located. Manual checking and building were performed in Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004), and refinement was done using the Crystallography & NMR system (Brünger et al., 1998) and REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1997) with noncrystallographic symmetry restraints and translation libration screw refinement. The topology and parameter files of ligand molecules were generated by HIC-Up, and their positions and conformations were validated by |Fo−Fc| map (Kleywegt, 2007). Structure analysis and stereochemical quality were done with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993) and MOLPROBITY (Chen et al., 2010). The Ramachandran plots of WT-AtPPPS and SM-AtPPPS calculated by MOLPROBITY indicated 96.7%/2.8%/0.2% and 96%/3.2%/0.8% residues in favored/allowed/outside regions, respectively. The crystallographic statistics are listed in Supplemental Table S1. High-quality images of the molecular structures were created with PyMOL (DeLano, 2002; http://www.pymol.org/).

Enzymatic Assay

The biochemical assays followed similar protocols as described previously (Guo et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006, 2010; Hsieh et al., 2010). The substrate mixtures (10 μm C5-DMAPP with 150 μm C5-[14C]IPP, 10 μm C10-GPP with 140 μm C5-[14C]IPP, 10 μm C15-FPP with 130 μm C5-[14C]IPP, and 10 μm C20-GGPP with 120 μm C5-[14C]IPP) were incubated with 1 μm enzyme for 24 h at 25°C in the reaction buffer (100 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.1% [w/v] Triton X-100, 5 mm MgCl2, and 50 mm KCl) for the determination of product chain length. The products were separated by thin-layer chromatography using acetone:water (29:1) as the mobile phase.

Genetic Complementation Assay

The construct pACCAR25ΔcrtE containing the crt gene cluster except the deleted crtE encoding GGPPS was prepared for the identification of GGPPS activity (Misawa et al., 1990; Zhu et al., 1997; Kainou et al., 1999; Engprasert et al., 2004; Ye et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2010). The empty vectors of pET-16 and ScGGPPS/pET-32 (yeast GGPPS) were used here. The constructs were cotransformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3), harvesting pACCAR25ΔcrtE, and supplying 100 μg mL−1 ampicillin and 34 μg mL−1 choramphenicol. The transformed E. coli cells were induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-thiogalactopyranoside for 72 h at 20°C in Luria-Bertani medium. To quantify the yellow carotenoid, the same wet weight pellets were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 90% (v/v) acetone to extract the pigment. The concentration of pigment was measured by absorption at a wavelength of 450 nm (Perkin-Elmer Lambda Bio40).

Phylogenetic Analysis

The full-length amino acid sequences were aligned by using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). The evolution history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). The percentage of replicate trees that were evaluated by using the bootstrap test with 1,000 replicates is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolution distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic tree was made by using MEGA4 (Tamura et al., 2007).

The abbreviations and accession numbers used are as follows: La, Lupinus albus FPPS (U15777); Aa, Artemisia annua FPPS (U36376); Zm, Zea mays FPPS (L39789); At, Arabidopsis FPPS1 (AT5G47770); At, Arabidopsis FPPS2 (AT4G17190); At, Arabidopsis PPPS (AT2G34630); Cr, Catharanthus roseus GPPS (ACC77966); Cs, Citrus sinensis GPPS (CAC16851); Qr, Quercus robur GPPS (CAC20852); Sl, Solanum lycopersicum GPPS (ABB88703); Vv, Vitis vinifera GPPS (AAR08151); Os, Oryza sativa SPPS (NM_001062973); Sl, S. lycopersicum SPPS (DQ889204); Hb, Hevea brasiliensis SPPS (DQ437520); At, Arabidopsis SPPS1 (AT1G78510); At, Arabidopsis SPPS2 (AT1G17050); Am, Antirrhinum majus SSU (AAS82859); Hl, Humulus lupulus SSU (ACQ90681); Mp, Mentha piperita SSU (ABW86880); At, Arabidopsis SSU (AT4G38460); Sa, Sinapis alba GGPPS (CAA67330); Hl, H. lupulus LSU (ACQ90682); Am, A. majus LSU (AAS82860); Mp, M. piperita LSU (ABW86879); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS1 (AT1G49530); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS2 (AT2G18620); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS3 (AT2G18640); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS4 (AT2G23800); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS5 (AT3G14510); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS6 (AT3G14530); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS7 (AT3G14550); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS8 (AT3G20160); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS9 (AT3G29430); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS10 (AT3G32040); At, Arabidopsis GGPPS11 (AT4G36810); Ag, Abies grandis GPPS (AF513111); Pa, Picea abies GPPS (EU432047); Pa, P. abies GPPS/GGPPS (GQ369788). Coordinates and structure factors of WT-AtPPPS and SM-AtPPPS were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) with codes 3APZ and 3AQ0, respectively.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Multiple sequence alignment of heteromeric and homomeric AtGPPS.

Supplemental Figure S2. Multiple sequence alignment of plant GPPSs.

Supplemental Figure S3. Amino acid sequence alignment of plant PTSs.

Supplemental Figure S4. Time-course assays of substrate and product specificities of WT-AtPPPS.

Supplemental Figure S5. Analytic gel filtration of WT-AtPPPS.

Supplemental Figure S6. Products synthesized by SM-AtPPPS.

Supplemental Figure S7. The additional crystal contacts are used to facilitate crystal lattice formation.

Supplemental Figure S8. The architectures of SM-AtPPPS individual dimers and electron density maps for the ligands.

Supplemental Figure S9. Subunit comparisons of WT-AtPPPS and SM-AtPPPS.

Supplemental Figure S10. Optical absorption was used to quantify the accumulated yellow carotenoid in E. coli carrying pACCAR25ΔcrtE and respective vectors.

Supplemental Table S1. Full-length amino acid sequence relatedness of AtPPPS with GPPSs from angiosperms and SPPSs.

Supplemental Table S2. The primers used to construct the following clones and mutants of AtPPPS.

Supplemental Table S3. The BLAST relatedness of AtPPPS and other plant PTSs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Makoto Kawamukai (Shimane University) for providing the construct pACCAR25ΔcrtE, the Photon Factory and Spring-8 for beam time allocations, and Dr. Cheng-Chung Lee (Academia Sinica) for collecting the SM-AtPPPS diffraction data.

References

- Aharoni A, Giri AP, Deuerlein S, Griepink F, de Kogel WJ, Verstappen FW, Verhoeven HA, Jongsma MA, Schwab W, Bouwmeester HJ. (2003) Terpenoid metabolism in wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell 15: 2866–2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artz JD, Dunford JE, Arrowood MJ, Dong A, Chruszcz M, Kavanagh KL, Minor W, Russell RG, Ebetino FH, Oppermann U, et al. (2008) Targeting a uniquely nonspecific prenyl synthase with bisphosphonates to combat cryptosporidiosis. Chem Biol 15: 1296–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier F, Suire C, d’Harlingue A, Backhaus RA, Camara B. (2000) Molecular cloning of geranyl diphosphate synthase and compartmentation of monoterpene synthesis in plant cells. Plant J 24: 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT. (1993) Assessment of phase accuracy by cross validation: the free R value. Methods and applications. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 49: 24–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 54: 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C, Croteau R. (2002) Geranyl diphosphate synthase from Abies grandis: cDNA isolation, functional expression, and characterization. Arch Biochem Biophys 405: 130–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke CC, Wildung MR, Croteau R. (1999) Geranyl diphosphate synthase: cloning, expression, and characterization of this prenyltransferase as a heterodimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 13062–13067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Cervantes M, Gallagher CE, Zhu C, Wurtzel ET. (2006) Maize cDNAs expressed in endosperm encode functional farnesyl diphosphate synthase with geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase activity. Plant Physiol 141: 220–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TH, Guo RT, Ko TP, Wang AH, Liang PH. (2006) Crystal structure of type-III geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the mechanism of product chain length determination. J Biol Chem 281: 14991–15000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TH, Hsieh FL, Ko TP, Teng KH, Liang PH, Wang AH. (2010) Structure of a heterotetrameric geranyl pyrophosphate synthase from mint (Mentha piperita) reveals intersubunit regulation. Plant Cell 22: 454–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Poulter CD. (1993) Purification and characterization of farnesyl diphosphate/geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase: a thermostable bifunctional enzyme from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J Biol Chem 268: 11002–11007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Tholl D, D’Auria JC, Farooq A, Pichersky E, Gershenzon J. (2003) Biosynthesis and emission of terpenoid volatiles from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Cell 15: 481–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66: 12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowtan K. (2006) The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62: 1002–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AR, Pylatuik JD, Paradis JC, Low NH. (1998) Nectar-carbohydrate production and composition vary in relation to nectary anatomy and location within individual flowers of several species of Brassicaceae. Planta 205: 305–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphic System. DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA [Google Scholar]

- Derewenda ZS. (2004) Rational protein crystallization by mutational surface engineering. Structure 12: 529–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N, Pichersky E. (2000) Biochemical and molecular genetic aspects of floral scents. Plant Physiol 122: 627–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engprasert S, Taura F, Kawamukai M, Shoyama Y. (2004) Molecular cloning and functional expression of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase from Coleus forskohlii Briq. BMC Plant Biol 4: 1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershenzon J, Dudareva N. (2007) The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat Chem Biol 3: 408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt L, Cooper DR, Derewenda ZS, Eisenberg D. (2007) Toward rational protein crystallization: a Web server for the design of crystallizable protein variants. Protein Sci 16: 1569–1576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo RT, Kuo CJ, Chou CC, Ko TP, Shr HL, Liang PH, Wang AH. (2004) Crystal structure of octaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase from hyperthermophilic Thermotoga maritima and mechanism of product chain length determination. J Biol Chem 279: 4903–4912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirooka K, Bamba T, Fukusaki E, Kobayashi A. (2003) Cloning and kinetic characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana solanesyl diphosphate synthase. Biochem J 370: 679–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosfield DJ, Zhang Y, Dougan DR, Broun A, Tari LW, Swanson RV, Finn J. (2004) Structural basis for bisphosphonate-mediated inhibition of isoprenoid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 279: 8526–8529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao YY, Jeng MF, Tsai WC, Chuang YC, Li CY, Wu TS, Kuoh CS, Chen WH, Chen HH. (2008) A novel homodimeric geranyl diphosphate synthase from the orchid Phalaenopsis bellina lacking a DD(X)2-4D motif. Plant J 55: 719–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh FL, Chang TH, Ko TP, Wang AH. (2010) Enhanced specificity of mint geranyl pyrophosphate synthase by modifying the R-loop interactions. J Mol Biol 404: 859–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ME. (1971) The population genetics of Arabidopsis thaliana. I. The breeding system. Heredity 27: 39–50 [Google Scholar]

- Jun L, Saiki R, Tatsumi K, Nakagawa T, Kawamukai M. (2004) Identification and subcellular localization of two solanesyl diphosphate synthases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 1882–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kainou T, Kawamura K, Tanaka K, Matsuda H, Kawamukai M. (1999) Identification of the GGPS1 genes encoding geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthases from mouse and human. Biochim Biophys Acta 1437: 333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh KL, Guo K, Dunford JE, Wu X, Knapp S, Ebetino FH, Rogers MJ, Russell RG, Oppermann U. (2006) The molecular mechanism of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates as antiosteoporosis drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7829–7834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan RM, Winn MD. (2008) MrBUMP: an automated pipeline for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 64: 119–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg BA, Poulter CD. (1997) Chain elongation in the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway. Curr Opin Chem Biol 1: 570–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler A, Baldwin IT. (2001) Defensive function of herbivore-induced plant volatile emissions in nature. Science 291: 2141–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby J, Keasling JD. (2009) Biosynthesis of plant isoprenoids: perspectives for microbial engineering. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 335–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ. (2007) Crystallographic refinement of ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 63: 94–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloer DP, Welsch R, Beyer P, Schulz GE. (2006) Structure and reaction geometry of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase from Sinapis alba. Biochemistry 45: 15197–15204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange BM, Ghassemian M. (2003) Genome organization in Arabidopsis thaliana: a survey for genes involved in isoprenoid and chlorophyll metabolism. Plant Mol Biol 51: 925–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst 26: 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- Lebedev AA, Vagin AA, Murshudov GN. (2008) Model preparation in MOLREP and examples of model improvement using x-ray data. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 64: 33–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang PH. (2009) Reaction kinetics, catalytic mechanisms, conformational changes, and inhibitor design for prenyltransferases. Biochemistry 48: 6562–6570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang PH, Ko TP, Wang AH. (2002) Structure, mechanism and function of prenyltransferases. Eur J Biochem 269: 3339–3354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y, Li ZH, Miranda K, Oldfield E, Moreno SN. (2007) The farnesyl-diphosphate/geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthase of Toxoplasma gondii is a bifunctional enzyme and a molecular target of bisphosphonates. J Biol Chem 282: 30804–30816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucast LJ, Batey RT, Doudna JA. (2001) Large-scale purification of a stable form of recombinant tobacco etch virus protease. Biotechniques 30: 544–546, 548, 550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ. (2007) Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 63: 32–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa N, Nakagawa M, Kobayashi K, Yamano S, Izawa Y, Nakamura K, Harashima K. (1990) Elucidation of the Erwinia uredovora carotenoid biosynthetic pathway by functional analysis of gene products expressed in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 172: 6704–6712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53: 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura K, Koyama T. (1998) Enzymatic aspects of isoprenoid chain elongation. Chem Rev 98: 1263–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnuma S, Hirooka K, Hemmi H, Ishida C, Ohto C, Nishino T. (1996) Conversion of product specificity of archaebacterial geranylgeranyl-diphosphate synthase: identification of essential amino acid residues for chain length determination of prenyltransferase reaction. J Biol Chem 271: 18831–18837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlova I, Nagegowda DA, Kish CM, Gutensohn M, Maeda H, Varbanova M, Fridman E, Yamaguchi S, Hanada A, Kamiya Y, et al. (2009) The small subunit of snapdragon geranyl diphosphate synthase modifies the chain length specificity of tobacco geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase in planta. Plant Cell 21: 4002–4017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Macromolecular Crystallography 276: 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichersky E, Noel JP, Dudareva N. (2006) Biosynthesis of plant volatiles: nature’s diversity and ingenuity. Science 311: 808–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4: 406–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Gershenzon J. (2008) Cloning and characterization of two different types of geranyl diphosphate synthases from Norway spruce (Picea abies). Phytochemistry 69: 49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Wächtler B, Temp U, Krekling T, Séguin A, Gershenzon J. (2010) A bifunctional geranyl and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase is involved in terpene oleoresin formation in Picea abies. Plant Physiol 152: 639–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbacher R, Godzik A, Grzechnik SK, Jaroszewski L. (2004) The importance of alignment accuracy for molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60: 1229–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snape JW, Lawrence MJ. (1971) Breeding system of Arabidopsis thaliana. Heredity 27: 299–301 [Google Scholar]

- Soll J, Schultz G, Joyard J, Douce R, Block MA. (1985) Localization and synthesis of prenylquinones in isolated outer and inner envelope membranes from spinach chloroplasts. Arch Biochem Biophys 238: 290–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HY, Ko TP, Kuo CJ, Guo RT, Chou CC, Liang PH, Wang AH. (2005) Homodimeric hexaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase from the thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus displays asymmetric subunit structures. J Bacteriol 187: 8137–8148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. (2007) MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24: 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarshis LC, Proteau PJ, Kellogg BA, Sacchettini JC, Poulter CD. (1996) Regulation of product chain length by isoprenyl diphosphate synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 15018–15023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholl D, Kish CM, Orlova I, Sherman D, Gershenzon J, Pichersky E, Dudareva N. (2004) Formation of monoterpenes in Antirrhinum majus and Clarkia breweri flowers involves heterodimeric geranyl diphosphate synthases. Plant Cell 16: 977–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandermoten S, Charloteaux B, Santini S, Sen SE, Béliveau C, Vandenbol M, Francis F, Brasseur R, Cusson M, Haubruge E. (2008) Characterization of a novel aphid prenyltransferase displaying dual geranyl/farnesyl diphosphate synthase activity. FEBS Lett 582: 1928–1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schie CC, Ament K, Schmidt A, Lange T, Haring MA, Schuurink RC. (2007) Geranyl diphosphate synthase is required for biosynthesis of gibberellins. Plant J 52: 752–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Dixon RA. (2009) Heterodimeric geranyl(geranyl)diphosphate synthase from hop (Humulus lupulus) and the evolution of monoterpene biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 9914–9919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Schalk M, Clark A, Miles RB, Coates R, Chappell J. (2006) Redirection of cytosolic or plastidic isoprenoid precursors elevates terpene production in plants. Nat Biotechnol 24: 1441–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Fujii M, Hirata A, Kawamukai M, Shimoda C, Nakamura T. (2007) Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase in fission yeast is a heteromer of farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPS), Fps1, and an FPS-like protein, Spo9, essential for sporulation. Mol Biol Cell 18: 3568–3581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XF, Suzuki K, Okada K, Tanaka K, Nakagawa T, Kawamukai M, Matsuda K. (1997) Cloning and functional expression of a novel geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase gene from Arabidopsis thaliana in Escherichia coli. Plant Cell Physiol 38: 357–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.