Abstract

Purpose

Impaired microvascular perfusion in sepsis is not treated effectively because its mechanism is unknown. Since inflammatory and coagulation pathways cross-activate, we tested if stoppage of blood flow in septic capillaries is due to oxidant-dependent adhesion of platelets in these microvessels.

Methods

Sepsis was induced in wild type, eNOS−/−, iNOS−/−, and gp91phox−/− mice (n = 14–199) by injection of feces into the peritoneum. Platelet adhesion, fibrin deposition, and blood flow stoppage in capillaries of hindlimb skeletal muscle were assessed by intravital microscopy. Prophylactic treatments at the onset of sepsis were intravenous injection of platelet-depleting antibody, P-selectin blocking antibody, ascorbate, or antithrombin. Therapeutic treatments (delayed until 6 h) were injection of ascorbate or the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor eptifibatide, or local superfusion of the muscle with NOS cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin or NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP).

Results

Sepsis at 6–7 h markedly increased the number of stopped-flow capillaries and the occurrence of platelet adhesion and fibrin deposition in these capillaries. Platelet depletion, iNOS and gp91phox deficiencies, P-selectin blockade, antithrombin, or prophylactic ascorbate prevented, whereas delayed ascorbate, eptifibatide, tetrahydrobiopterin, or SNAP reversed, septic platelet adhesion and/or flow stoppage. The reversals by ascorbate and tetrahydrobiopterin were absent in eNOS−/− mice. Platelet adhesion predicted 90% of capillary flow stoppage.

Conclusion

Impaired perfusion and/or platelet adhesion in septic capillaries requires NADPH oxidase, iNOS, P-selectin, and activated coagulation, and is inhibited by intravenous administration of ascorbate and by local superfusion of tetrahydrobiopterin and NO. Reversal of flow stoppage by ascorbate and tetrahydrobiopterin may depend on local eNOS-derived NO which dislodges platelets from the capillary wall.

Keywords: Microcirculation, Ascorbate, Nitric oxide, Platelets, Fibrin

Introduction

Severe sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response in which impaired microvascular perfusion precipitates organ failure and death [1]. Impaired perfusion is seen as increased number of stopped-flow capillaries and decreased number of perfused capillaries [2]. The impairment increases the diffusion distance for oxygen to parenchymal cells, leading to tissue hypoxia and organ failure [3, 4]. Septic impairment of capillary blood flow has been visualized in animal organs by intravital microscopy [2, 5] and in human tissues by orthogonal polarization spectral imaging and sidestream dark-field imaging [6, 7]. Despite the prevalence of capillary flow impairment and its importance in determining the clinical outcome of sepsis [6], the mechanisms of this impairment are unknown [8].

Intravascular coagulation in sepsis [9, 10] could be a contributory mechanism. Inflammatory and coagulation pathways cross-activate [11], including initiation of coagulation and activation of platelets by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and inflammatory cytokines [11, 12], as well as augmentation of inflammation by activated platelets [13–17]. Therefore, sepsis-induced platelet adhesion to capillary endothelium, platelet aggregates, and/or subsequently formed microthrombi could plug capillaries. To our knowledge, there is no report addressing this possible mechanism. The overall aim of the present study was to use high-resolution intravital microscopy to examine in “real time” platelet adhesion and microthrombi formation in septic capillaries. The study had two specific objectives. First, we used treatments known to affect platelet and coagulation functions to establish the role of these functions in blood flow stoppage in septic capillaries. Second, we manipulated the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) in the microvasculature to determine if the role of platelets in septic blood flow stoppage is oxidant- and NO-dependent. We discovered that platelet adhesion co-localized with fibrin deposition in septic capillaries contributes critically to blood flow stoppage.

Methods

Details of animal preparation, intravital microscopy, and biochemical and blood platelet count analyses are given in the “Electronic supplementary material”. We used a fluid resuscitated model of polymicrobial sepsis in male wild type, eNOS−/−, iNOS−/−, and gp91phox−/− mice injected with feces into the peritoneum (FIP). For controls, we used naive or sham mice (saline-injected intraperitoneally). At 6–7 h post-FIP, the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle was prepared for intravital microscopy to determine the percentage of stopped-flow capillaries, the number of adhering platelets and leukocytes per millimeter of capillary length, and the percentage of fibrin-containing capillaries. Capillary blood flow impairment in the EDL muscle is established at 6–7 h post-FIP [18].

Experimental design

Role of platelet and coagulation functions in blood flow stoppage

We studied septic mice with lactate above 1 mmol/L at 6–7 h post-FIP. To determine if platelets are required for blood flow stoppage in septic capillaries, mice were injected intravenously with platelet-depleting antibody at 0.5 h post-FIP (5 μL/mouse), P-selectin blocking antibody (2 mg/kg in 0.1 mL saline, time 0), or control immunoglobulin (2 mg/kg). P-selectin is a key adhesion protein mediating platelet–endothelial interaction [21]. To examine the role of activated coagulation, mice were injected intravenously with antithrombin (250 U/kg, 0.5 h), a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, eptifibatide (180 μg/kg, 6 h), or saline. Thrombin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa are required for fibrin and thrombus formation [22]. Finally, to assess the thrombogenic potential of the septic capillary bed at 6 h, we flooded the EDL muscle with FeCl3 solution (50 mmol/L in saline, 0.1-mL volume, 5 min) and then examined capillary blood flow. Topical application of FeCl3 is a conventional approach to assess thrombosis in microvessels [23].

Roles ROS and NO in platelet adhesion in the septic capillary bed

To examine the role of ROS, mice were injected intravenously with the antioxidant ascorbate (10 mg/kg; freshly dissolved, 0 or 6 h) or saline. Alternatively, we used mice with genetically deleted gp91phox, a subunit of NADPH oxidase (major source of ROS in septic microvasculature [24]). To assess the role of iNOS-derived NO, we used iNOS−/− mice. To examine the role of local NO available near capillaries, we flooded the EDL muscle with the NOS cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4; 0.1 μmol/L, in repeated 0.1-mL bolus applications over 1 h), the NO donor S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP; 5 μmol/L in one 0.1-mL bolus), decomposed SNAP, or saline. The glass coverslip normally covering the muscle surface was slightly lifted to permit introduction of the bolus between the muscle surface and coverslip. To determine if the effects of ascorbate and BH4 treatments were eNOS-dependent, ascorbate/BH4 treatments were done in eNOS−/− mice.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SE; n indicates the number of mice (one muscle/mouse). Data were analyzed by student t test or ANOVA followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Significance was assigned as p < 0.05.

Results

Role of platelet and coagulation functions in blood flow stoppage

Sepsis markedly increased blood flow stoppage in capillaries (Fig. 1; control data in naive and sham-injected mice did not differ, and were therefore pooled here). No stoppage was seen in arterioles or venules. Sepsis also markedly increased platelet adherence and fibrin deposition in capillaries (Fig. 1). We observed single-adhering platelets and aggregates up to five platelets. Platelets adhered in stopped-flow capillaries (4.5 ± 1.0, n = 7) rather than in perfused capillaries (0.2 ± 0.1 platelets/mm, n = 7). The number of adherent leukocytes in capillaries was negligible (not different from zero in control and septic mice, “Electronic supplementary material”). Formed fibrin occurred only in stopped-flow capillaries; none was seen in arterioles/venules. We also determined platelet adhesion specifically in capillaries with formed fibrin. Platelet adhesion in these specific septic capillaries was more extensive (3.6 ± 0.8 platelets/mm, n = 4) than adhesion in any septic capillaries (1.6/mm, Fig. 1), confirming that septic platelet adhesion and fibrin deposition occurred in the same capillaries.

Fig. 1.

Sepsis increases blood flow stoppage, platelet adhesion, and fibrin deposition in capillaries in mouse skeletal muscle. Sepsis was induced by injection of feces into peritoneum (FIP). Flow stoppage was determined in 18 control and 16 septic mice at 6–7 h, adhesion in 9 control and 7 and septic mice at 7 h, and fibrin deposition in 2 control and 4 and septic mice at 7 h post-FIP, *Difference from control, p < 0.05

Platelet-depleting antibody dramatically lowered serum platelet counts in control (from 850 ± 50 to 40 ± 20) and septic mice (610 ± 40 to 60 ± 20 × 109/L) (n = 8–13). In septic mice, the antibody decreased the abundance of stopped-flow capillaries (41 ± 2 to 28 ± 2%, p < 0.05, n = 16, 12, respectively), implicating platelets in septic impairment of capillary flow.

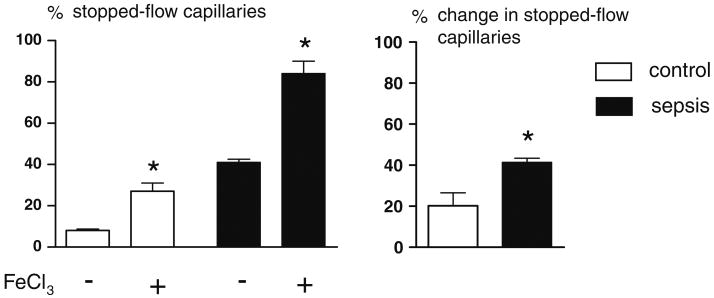

P-selectin blockade, antithrombin, and eptifibatide significantly reduced platelet adhesion and blood flow stoppage in septic capillaries (Fig. 2), indicating that P-selectin and coagulation activation were required for this adhesion/stoppage. Injection of control immunoglobulin or saline did not affect septic adhesion/stoppage (data not shown). Finally, topical FeCl3 stopped flow more extensively in septic than control capillaries (Fig. 3), suggesting that sepsis increased the propensity of microthrombi formation in capillaries.

Fig. 2.

Injections of P-selectin blocking antibody at 0.5 h, eptifibatide at 6 h (glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor), and antithrombin at 0.5 h inhibited platelet adhesion and blood flow stoppage in capillaries at 6–7 h post-FIP. *Difference from sepsis, p < 0.05, n = 5–9 for adhesion groups, and 5–16 for stopped-flow groups

Fig. 3.

Sepsis increases thrombosis in capillaries. The thrombosis potential was tested by flooding the muscle with FeCl3 at 6 h post-FIP. Left *Difference between post-FeCl3 and pre-FeCl3 percentage of stopped-flow capillaries, p < 0.05, n = 5–18. Right Change in stopped flow percentage = (post-FeCl3 percentage) − (pre-FeCl3 percentage). *Difference from control, p < 0.05, n = 5 per group

Role of ROS and NO

Prophylactic injection of ascorbate, or gp91phox deletion, prevented platelet adhesion and flow stoppage in septic capillaries (Fig. 4). Moreover, delayed injection of ascorbate reversed septic adhesion/stoppage (Fig. 5). These latter effects were eNOS-dependent, since they were absent in eNOS−/− mice (Fig. 5). BH4 and NO donor SNAP at 6–7 h significantly reduced septic platelet adhesion and flow stoppage (Fig. 6, top). Decomposed SNAP or saline did not affect septic flow stoppage (data not shown). The reversal effects of BH4 were eNOS-dependent, since they were absent in eNOS−/− mice (Fig. 6). Consistently, the effects of SNAP did not depend on eNOS (Fig. 6). eNOS knockout did not affect blood flow stoppage and platelet adhesion in septic capillaries (Fig. 5), but iNOS knockout inhibited platelet adhesion (Fig. 6, bottom). Flow stoppage in control gp91phox−/−, eNOS−/−, and iNOS−/− mice (data not shown) was not statistically different from that of control wild type mice (Fig. 1).

Fig. 4.

Ascorbate injection at 0 h and gp91phox knockout prevent platelet adhesion and blood flow stoppage in capillaries at 6–7 h post-FIP, *Difference from sepsis wild type (wt) group, p < 0.05, n = 6–7 for adhesion groups, and 5–16 for stopped-flow groups

Fig. 5.

Ascorbate injection at 6 h reverses platelet adhesion and blood flow stoppage in capillaries at 7 h post-FIP in wild type but not eNOS−/− mice, *Difference from sepsis group, p < 0.05, n = 6–17 for adhesion groups, and 8–16 for stopped-flow groups

Fig. 6.

Effects of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and NO donor SNAP on platelet adhesion and blood flow stoppage in capillaries of wild type and eNOS−/− mice (top), and effect of iNOS knockout on adhesion/stoppage (bottom). At 6 h, 0.1-mL boluses of BH4 (repeated over 1 h period) flooded the muscle surface to determine platelet adhesion and flow stoppage at 7 h post-FIP. Alternatively, a single 0.1-mL bolus of SNAP flooded the surface, and platelet adhesion and stoppage were determined 15 min later (when the temporary SNAP-induced vasodilation had ended). BH4 reversed platelet adhesion and flow stoppage in septic capillaries of wild type but not eNOS−/− mice. SNAP reversed platelet adhesion and flow stoppage in both types of mice. iNOS knockout inhibited septic platelet adhesion at 6 h post-FIP. *Difference from appropriate sepsis group, p < 0.05, n = 5–10 for adhesion groups, and 5–16 for stopped-flow groups in top row, and 6 and 10 for adhesion, and 6 and 10 for stopped-flow groups at bottom, respectively

Discussion

The present study addressed the mechanism of blood flow stoppage in septic capillaries. We report for the first time that (1) sepsis markedly increases platelet adhesion, fibrin deposition, and propensity of thrombosis in capillaries; (2) capillary flow stoppage requires platelets, P-selectin, and coagulation activation; and (3) capillary platelet adhesion can be prevented or reversed by gp91phox and iNOS deficiencies, ascorbate, and local BH4 and exogenous NO.

Role of platelet and coagulation functions in blood flow stoppage

In the present study, platelets adhered in septic capillaries and septic venules as well [25]. However, unlike in capillaries, adhering platelets in venules were not associated with fibrin deposition or stopped blood flow, indicating that rheological findings in larger microvessels cannot be extended to capillaries. In view of negligible leukocyte adhesion observed in capillaries, we sought leukocyte-independent mechanism(s) of capillary plugging in sepsis.

Possible mechanisms could be platelet activation, aggregation, and subsequent critical narrowing/plugging of the capillary lumen by adhering platelets [13, 17], or plugging by adhering platelets and formed microthrombi within the capillary. LPS and inflammatory cytokines increase expression of P-selectin and von Willebrand factor on endothelial cells to initiate platelet adhesion [12, 26]. LPS and cytokines also increase tissue factor expression at the cell membrane of monocytes and endothelial cells [11], initiating coagulation. The present data are consistent with the mechanism of platelet adhesion and microthrombi formation. Sepsis increased platelet adhesion in capillaries, whereas platelet depletion and blockade of P-selectin significantly reduced septic blood flow stoppage (Fig. 2). Sepsis-induced platelet adhesion and fibrin deposition were seen to co-localize in stopped-flow capillaries, while anticoagulants decreased septic platelet adhesion and flow stoppage in capillaries (Figs. 1, 2).

In critically ill patients, a 30% drop in platelet count independently predicts death [27]. In the present study, a comparable 28% drop occurred in septic mice. Since the life span of platelets is longer than 6 h [28], we hypothesize that most of this platelet consumption is due to platelet adhesion in the microcirculation. To estimate how platelet adhesion in capillaries predicts septic blood flow stoppage, we used the present data to plot the mean values of stopped-flow capillaries (%) versus values of platelet adhesion per millimeter (“Electronic supplementary material”). The plot showed significant linear correlation, indicating that platelet adhesion in capillaries predicts ∼90% of capillary blood flow stoppage. If decreased platelet count were due to platelet adhesion in capillaries, then the 28% drop implicates a substantial plugging of the capillary bed (e.g., 40% plugging in skeletal muscle).

Role of ROS and NO in septic capillaries

We showed that sepsis increases ROS production in mouse skeletal muscle [29] and that septic capillary blood flow impairment depends on NADPH oxidase [18]. ROS promote expression of P-selectin at the surface of platelets and endothelial cells, and enhance platelet adhesion to the endothelium and coagulation [11, 30, 31]. Our data are consistent with ROS-mediated blood flow stoppage due to enhanced platelet adhesion in capillaries. The antioxidant ascorbate and gp91phox knockout prevented/reversed septic platelet adhesion and flow stoppage (Figs. 4, 5) (an effect consistent with ascorbate's ability to significantly improve septic mouse survival at 24 h) [18, 29].

Recently we proposed that increased ROS level in sepsis oxidizes the eNOS cofactor BH4, uncouples eNOS in platelets and endothelial cells, and thus stops NO production in these cells [18]. Because low physiological levels of NO are anti-aggregatory and anti-adhesive [31], uncoupled eNOS promotes platelet adhesion/aggregation and flow cessation in capillaries. The present data are consistent with this proposed mechanism. BH4 or NO applied locally reversed platelet adhesion and flow stoppage in septic capillaries (Fig. 6). Further, the beneficial effects of ascorbate and BH4 were eNOS-dependent (Figs. 5, 6).

Knockout of iNOS reduced septic platelet adhesion (Fig. 6, bottom), suggesting that iNOS-derived NO is pro-adhesive. At first glance, this result contradicts the beneficial effect of local NO (Fig. 6, top). To reconcile these observations, we note that iNOS enzymatic activity is negligible in the mouse skeletal muscle at 6 h of sepsis [18] and hypothesize that (1) iNOS activity is higher in other septic tissues and (2) NO overproduction here could promote platelet adhesion in the skeletal muscle. Excess NO could react with superoxide, form peroxynitrite [31], and lead to activation/priming of blood-borne platelets to adhere in tissues. The apparent opposing effects of NO (Fig. 6) underscore the complex role NOS/NO may play during sepsis [32, 33].

Methodological limitations

The use of the platelet-depleting antibody to study the role of platelets in septic blood flow stoppage was problematic. Both control and septic mice injected with the antibody were noticeably sicker than their non-injected counterparts (mice hunched in the cage, had erected fur, and did not respond to tactile stimuli). Further, the antibody significantly increased (40%) capillary flow stoppage in control mice. Consistent with reported increased mortality in mice by platelet-depleting antibody [34], the present deleterious effects of the antibody on animal health might have obscured the full beneficial effect of platelet depletion against septic capillary flow stoppage in skeletal muscle.

Finally, the present value of adherent platelets per millimeter in sepsis may underestimate the actual platelet adherence, since plugged septic capillaries may not permit plasma flow and detection of platelets with a fluorescent dye. Capillary obstructions could also limit the full impact of agents injected at 6 h on platelet adhesion and blood flow stoppage studied at 7 h.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that polymicrobial sepsis increases platelet adhesion and fibrin deposition in capillaries and that septic impairment of capillary blood flow requires platelet adhesion, P-selectin, and activated coagulation. Since platelet adhesion and capillary flow impairment can be inhibited by the antioxidant ascorbate and exogenous NO, administration of ascorbate and/or NO donors to attenuate platelet accumulation in septic capillaries is an important consideration for future development of novel adjuvant therapies for sepsis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank HSFO for funding (NA 5941, KT and JXW), and Ms. S. Milkovich, J. MacLean, and S. Sehgal for technical help.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00134-010-1969-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Dan Secor, Critical Illness Research, Victoria Research Laboratories, Lawson Health Research Institute, 6th Floor, 800 Commissioners Road East, London, ON N6C 2V5, Canada, Tel.: +1-519-6858500; Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

Fuyan Li, Critical Illness Research, Victoria Research Laboratories, Lawson Health Research Institute, 6th Floor, 800 Commissioners Road East, London, ON N6C 2V5, Canada, Tel.: +1-519-6858500; Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

Christopher G. Ellis, Critical Illness Research, Victoria Research Laboratories, Lawson Health Research Institute, 6th Floor, 800 Commissioners Road East, London, ON N6C 2V5, Canada, Tel.: +1-519-6858500; Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada

Michael D. Sharpe, Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Program in Critical Care, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada

Peter L. Gross, Department of Medicine, Henderson Research Centre, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

John X. Wilson, Department of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA

Karel Tyml, Email: ktyml@lhsc.on.ca, Critical Illness Research, Victoria Research Laboratories, Lawson Health Research Institute, 6th Floor, 800 Commissioners Road East, London, ON N6C 2V5, Canada, Tel.: +1-519-6858500; Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada; Department of Medical Biophysics, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

References

- 1.Vincent JL, Martinez EO, Silva E. Evolving concepts in sepsis definitions. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:665–675. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam C, Tyml K, Martin C, Sibbald W. Microvascular perfusion is impaired in a rat model of normotensive sepsis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2077–2083. doi: 10.1172/JCI117562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis CG, Bateman RM, Sharpe MD, Sibbald WJ, Gill R. Effect of a maldistribution of microvascular blood flow on capillary O2 extraction in sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H156–H164. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2002.282.1.H156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman RM, Walley KR. Microvascular resuscitation as a therapeutic goal in severe sepsis. Crit Care. 2005;9(Suppl 4):S27–S32. doi: 10.1186/cc3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, Patel KD, Chakrabarti S, McAvoy E, Sinclair GD, Keys EM, len-Vercoe E, Devinney R, Doig CJ, Green FH, Kubes P. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13:463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakr Y, Dubois MJ, De Backer D, Creteur J, Vincent JL. Persistent microcirculatory alterations are associated with organ failure and death in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1825–1831. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000138558.16257.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Draisma A, Bemelmans R, van der Hoeven JG, Spronk P, Pickkers P. Microcirculation and vascular reactivity during endotoxemia and endotoxin tolerance in humans. Shock. 2009;31:581–585. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318193e187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mariscalco MM. Unlocking (perhaps unblocking) the microcirculation in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:561–562. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000199075.70631.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amaral A, Opal SM, Vincent JL. Coagulation in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1032–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daudel F, Kessler U, Folly H, Lienert JS, Takala J, Jakob SM. Thromboelastometry for the assessment of coagulation abnormalities in early and established adult sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2009;13:R42. doi: 10.1186/cc7765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levi M, van der Poll T, Buller HR. Bidirectional relation between inflammation and coagulation. Circulation. 2004;109:2698–2704. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131660.51520.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindenblatt N, Menger MD, Klar E, Vollmar B. Systemic hypothermia increases PAI-1 expression and accelerates microvascular thrombus formation in endotoxemic mice. Crit Care. 2006;10:R148. doi: 10.1186/cc5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wassmer SC, de Souza JB, Frere C, Candal FJ, Juhan-Vague I, Grau GE. TGF-beta1 released from activated platelets can induce TNF-stimulated human brain endothelium apoptosis: a new mechanism for microvascular lesion during cerebral malaria. J Immunol. 2006;176:1180–1184. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Otterdal K, Smith C, Oie E, Pedersen TM, Yndestad A, Stang E, Endresen K, Solum NO, Aukrust P, Damas JK. Platelet-derived light induces inflammatory responses in endothelial cells and monocytes. Blood. 2006;108:928–935. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-010629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Bahrani A, Taha S, Shaath H, Bakhiet M. TNF-alpha and IL-8 in acute stroke and the modulation of these cytokines by antiplatelet agents. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007;4:31–37. doi: 10.2174/156720207779940716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong YI, Jung ID, Lee CM, Chang JH, Chun SH, Noh KT, Jeong SK, Shin YK, Lee WS, Kang MS, Lee SY, Lee JD, Park YM. The novel role of platelet-activating factor in protecting mice against lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxic shock. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lou J, Donati YR, Juillard P, Giroud C, Vesin C, Mili N, Grau GE. Platelets play an important role in TNF-induced microvascular endothelial cell pathology. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1397–1405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyml K, Li F, Wilson JX. Septic impairment of capillary blood flow requires nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase but not nitric oxide synthase and is rapidly reversed by ascorbate through an endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2355–2362. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818024f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamme C, Bundschuh DS, Hartung T, Gebert U, Wollin L, Nusing R, Wendel A, Uhlig S. Temporal sequence of pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses to graded polymicrobial peritonitis in mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5642–5650. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5642-5650.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reheman A, Gross P, Yang H, Chen P, Allen D, Leytin V, Freedman J, Ni H. Vitronectin stabilizes thrombi and vessel occlusion but plays a dual role in platelet aggregation. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:875–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McEver RP. P-selectin and PSGL-1: exploiting connections between inflammation and venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:364–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannel DN, Grau GE. Role of platelet adhesion in homeostasis and immunopathology. Mol Pathol. 1997;50:175–185. doi: 10.1136/mp.50.4.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westrick RJ, Winn ME, Eitzman DT. Murine models of vascular thrombosis (Eitzman series) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2079–2093. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu F, Tyml K, Wilson JX. iNOS expression requires NADPH oxidase-dependent redox signaling in microvascular endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:207–214. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vachharajani V, Vital S, Russell J, Granger DN. Hypertonic saline and the cerebral microcirculation in obese septic mice. Microcirculation. 2007;14:223–231. doi: 10.1080/10739680601139153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergmeier W, Chauhan AK, Wagner DD. Glycoprotein Ibalpha and von Willebrand factor in primary platelet adhesion and thrombus formation: lessons from mutant mice. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:264–270. doi: 10.1160/TH07-10-0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreau D, Timsit JF, Vesin A, Garrouste-Org, de Lassence A, Zahar JR, Adrie C, Vincent F, Cohen Y, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. Platelet count decline: an early prognostic marker in critically ill patients with prolonged ICU stays. Chest. 2007;131:1735–1741. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najean Y, Ardaillou N, Dresch C. Platelet lifespan. Annu Rev Med. 1969;20:47–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.20.020169.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu F, Wilson JX, Tyml K. Ascorbate protects against impaired arteriolar constriction in sepsis by inhibiting inducible nitric oxide synthase expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1282–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krotz F, Sohn HY, Pohl U. Reactive oxygen species: players in the platelet game. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1988–1996. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000145574.90840.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ovechkin AV, Lominadze D, Sedoris KC, Robinson TW, Tyagi SC, Roberts AM. Lung ischemia-reperfusion injury: implications of oxidative stress and platelet-arteriolar wall interactions. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2007;113:1–12. doi: 10.1080/13813450601118976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange M, Enkhbaatar P, Nakano Y, Traber DL. Role of nitric oxide in shock: the large animal perspective. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1979–1989. doi: 10.2741/3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cauwels A. Nitric oxide in shock. Kidney Int. 2007;72:557–565. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujimi S, MacConmara MP, Maung AA, Zang Y, Mannick JA, Lederer JA, Lapchak PH. Platelet depletion in mice increases mortality after thermal injury. Blood. 2006;107:4399–4406. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.