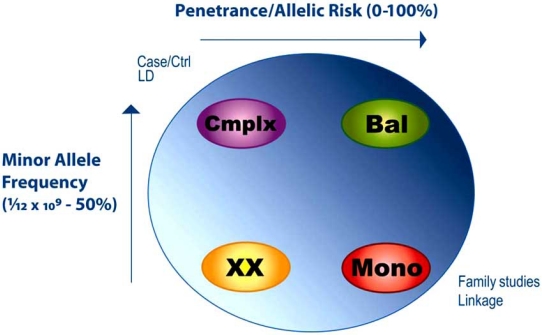

Fig. (1). Monogenic versus complex phenotypes.

Genetic variants may be anywhere between vanishingly rare (with a minor allele frequency at a minimum of one in the entire human population of approximately 6 billion, thus an allele frequency of 1/12x109 chromosomes) up to 50% (after which the minor allele becomes the major allele). The physiological effect of a genetic variant may be individually very strong (high penetrance) or weak (low penetrance). Rare high penetrance alleles have historically been identified in families, and studied by genome-wide scanning with dense polymorphic anonymous markers, currently SNPs, followed by statistical linkage analysis and gene resequencing to identify causal variants in the family. Common low penetrance alleles are typically identified in large case/control cohorts, and studied by genome-wide SNP genotyping followed by simple statistical tests of differential allele frequency in the two classes, or by more sophisticated linkage disequilibrium (haplotype) mapping. Common high penetrance variants are unusual, since these would normally be either quickly fixed or eliminated from breeding populations. One circumstance under which such variants can be maintained is balanced selection, where there are opposing selections on heterozygotes versus homozygotes (malaria and sickle cell anemia being the best documented example). Rare variants of small functional effect are easily discovered through random resequencing but difficult to study mechanistically.