Abstract

Gap junctions first appear during compaction in the eight-cell stage of mouse development. Their assembly can be initiated in the near absence of transcription and protein synthesis from the four-cell stage, indicating the existence of preformed precursors. We have investigated the temporal control of this event, focusing on the possible involvement of the cytoskeleton, cell flattening, and cytokinesis. Embryos in various cleavage stages were treated with cytochalasins, to disrupt microfilaments and block cell flattening, cytokinesis, or both, or nocodazole, to promote microtubule depolymerization. To assess their capacity to initiate gap junction assembly after such treatments, the embryos were then aggregated with communication-competent, compacted embryos that had been labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate. Passage of the fluorescent dye, carboxyfluorescein, from labeled to unlabeled embryo was taken as evidence that interembryonic junction formation had occurred. The capacity to assemble gap junctions was acquired at the normal time by embryos prevented by cytochalasin treatment from undergoing cell flattening or any cytokinesis from fertilization onward. Likewise, treatment with nocodazole beginning in the four-cell or early eight-cell stage did not interfere with gap junction assembly. Neither drug affected the inability of four-cell embryos to assemble gap junctions prematurely. We conclude that intact microfilament or microtubule networks are not required for gap junction assembly in this system, nor do they restrain junctional precursors from assembling prematurely. Furthermore, the timing of gap junction assembly is not linked to cell flattening, cytokinesis, or cell number.

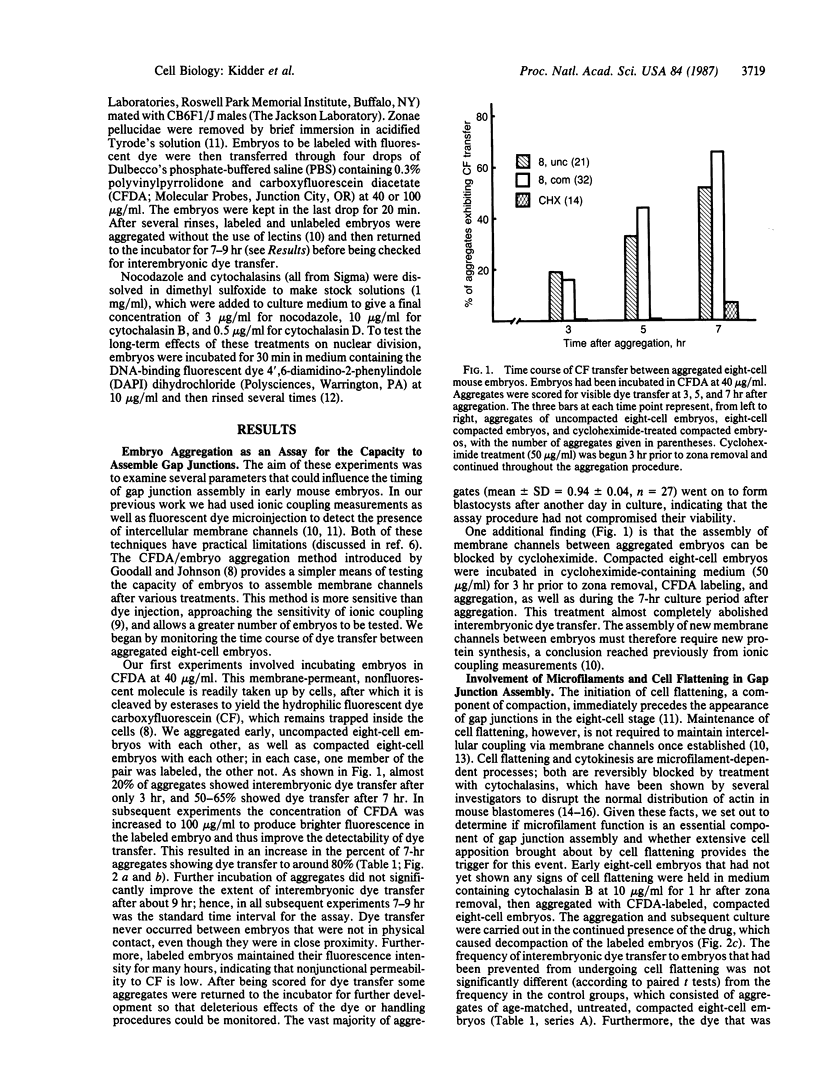

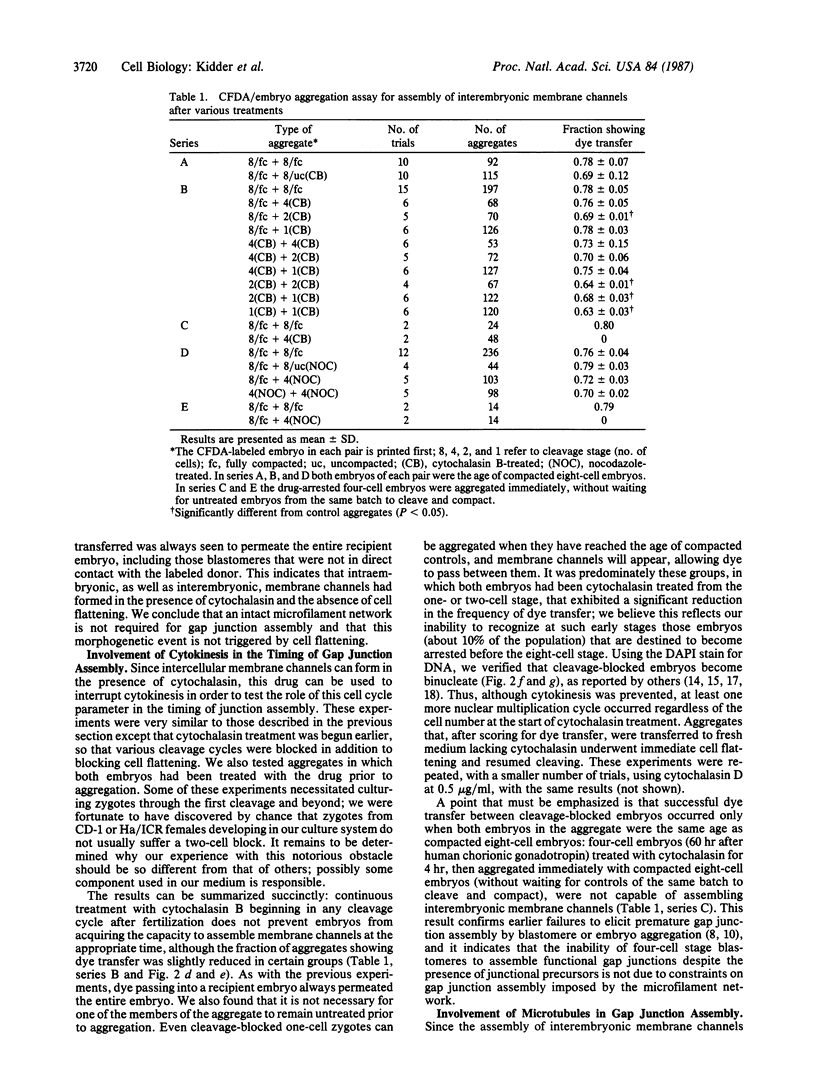

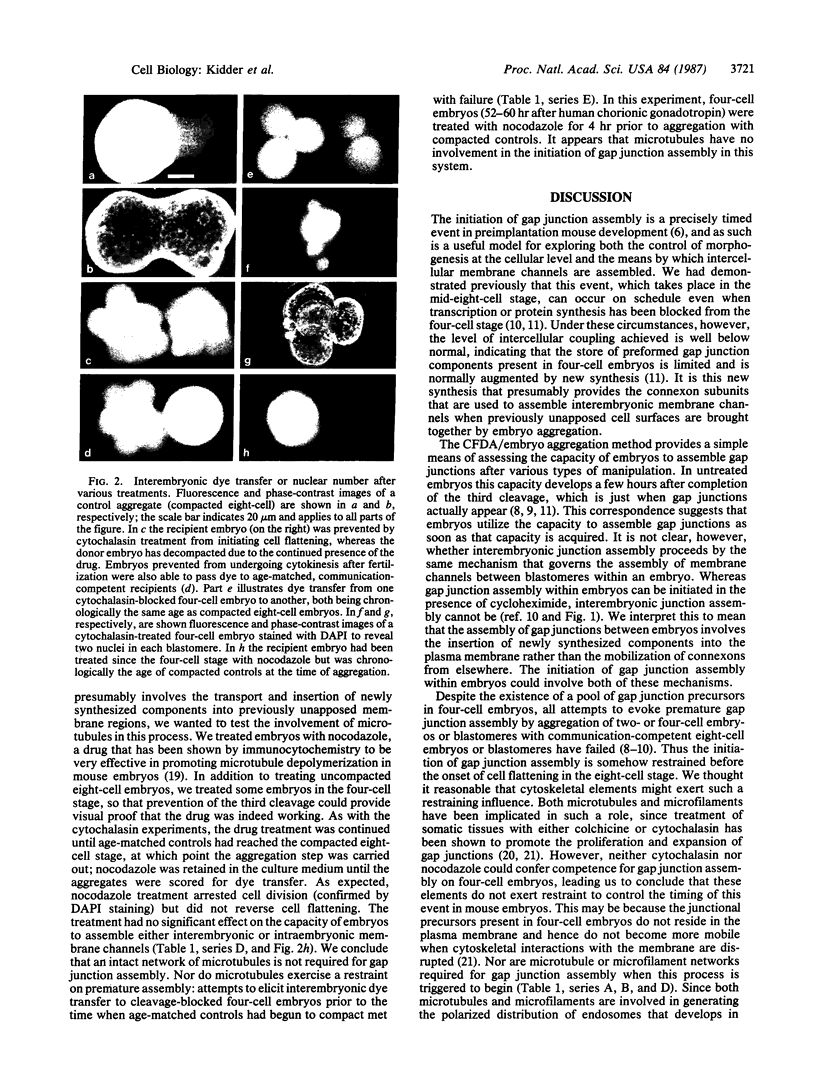

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Caveney S. The role of gap junctions in development. Annu Rev Physiol. 1985;47:319–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.47.030185.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermietzel R., Leibstein A., Frixen U., Janssen-Timmen U., Traub O., Willecke K. Gap junctions in several tissues share antigenic determinants with liver gap junctions. EMBO J. 1984 Oct;3(10):2261–2270. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming T. P., Cannon P. M., Pickering S. J. The cytoskeleton, endocytosis and cell polarity in the mouse preimplantation embryo. Dev Biol. 1986 Feb;113(2):406–419. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall H., Johnson M. H. The nature of intercellular coupling within the preimplantation mouse embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984 Feb;79:53–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall H., Johnson M. H. Use of carboxyfluorescein diacetate to study formation of permeable channels between mouse blastomeres. Nature. 1982 Feb 11;295(5849):524–526. doi: 10.1038/295524a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall H. Manipulation of gap junctional communication during compaction of the mouse early embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1986 Feb;91:283–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall H., Maro B. Major loss of junctional coupling during mitosis in early mouse embryos. J Cell Biol. 1986 Feb;102(2):568–575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.2.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg E. L., Skibbens R. V. A protein homologous to the 27,000 dalton liver gap junction protein is present in a wide variety of species and tissues. Cell. 1984 Nov;39(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett S. K. A set of proteins showing cell cycle dependent modification in the early mouse embryo. Cell. 1986 May 9;45(3):387–396. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. H., Maro B. The distribution of cytoplasmic actin in mouse 8-cell blastomeres. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984 Aug;82:97–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber S. J., Surani M. A. Morphogenetic analysis of changing cell associations following release of 2-cell and 4-cell mouse embryos from cleavage arrest. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1981 Feb;61:331–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C. W., Gilula N. B. Gap junctional communication in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Cell. 1979 Oct;18(2):399–409. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein W. R. Junctional intercellular communication: the cell-to-cell membrane channel. Physiol Rev. 1981 Oct;61(4):829–913. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.4.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maro B., Pickering S. J. Microtubules influence compaction in preimplantation mouse embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1984 Dec;84:217–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlin J. R., Caveney S., Kidder G. M. Control of gap junction formation in early mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1983 Jul;98(1):155–164. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlin J. R., Kidder G. M. Intercellular junctional coupling in preimplantation mouse embryos: effect of blocking transcription or translation. Dev Biol. 1986 Sep;117(1):146–155. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J., Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: I. characterization and timing of cellular changes at the midblastula stage. Cell. 1982 Oct;30(3):675–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J., Kirschner M. A major developmental transition in early Xenopus embryos: II. Control of the onset of transcription. Cell. 1982 Oct;30(3):687–696. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. H., Kimler B. F., Smith T. K. Comparison of the supravital DNA dyes Hoechst 33342 and DAPI for flow cytometry and clonogenicity studies of human leukemic marrow cells. Exp Hematol. 1985 Nov;13(10):1039–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzoldt U. Expression of two surface antigens and paternal glucose-phosphate isomerase in polyploid one-cell mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 1986 Feb;113(2):512–516. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzoldt U. Regulation of stage-specific gene expression during early mouse development: effect of cytochalasin B and aphidicolin on stage-specific protein synthesis in mouse eggs. Cell Differ. 1984 Dec;15(2-4):163–167. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(84)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt H. P., Chakraborty J., Surani M. A. Molecular and morphological differentiation of the mouse blastocyst after manipulations of compaction with cytochalasin D. Cell. 1981 Oct;26(2 Pt 2):279–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassat J., Robenek H., Themann H. Alterations of tight and gap junctions in mouse hepatocytes following administration of colchicine. Cell Tissue Res. 1982;223(1):187–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00221509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas P. J., Misek D. E., Vega-Salas D. E., Gundersen D., Cereijido M., Rodriguez-Boulan E. Microtubules and actin filaments are not critically involved in the biogenesis of epithelial cell surface polarity. J Cell Biol. 1986 May;102(5):1853–1867. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh N., Ikegami S. A definite number of aphidicolin-sensitive cell-cyclic events are required for acetylcholinesterase development in the presumptive muscle cells of the ascidian embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1981 Feb;61:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh N. Recent advances in our understanding of the temporal control of early embryonic development in amphibians. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985 Nov;89 (Suppl):257–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. K., Johnson M. H. DNA replication and compaction in the cleaving embryo of the mouse. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1985 Oct;89:133–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surani M. A., Barton S. C., Burling A. Differentiation of 2-cell and 8-cell mouse embryos arrested by cytoskeletal inhibitors. Exp Cell Res. 1980 Feb;125(2):275–286. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surani M. A., Barton S. C., Norris M. L. Nuclear transplantation in the mouse: heritable differences between parental genomes after activation of the embryonic genome. Cell. 1986 Apr 11;45(1):127–136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadvalkar G., Pinto da Silva P. In vitro, rapid assembly of gap junctions is induced by cytoskeleton disruptors. J Cell Biol. 1983 May;96(5):1279–1287. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.5.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]