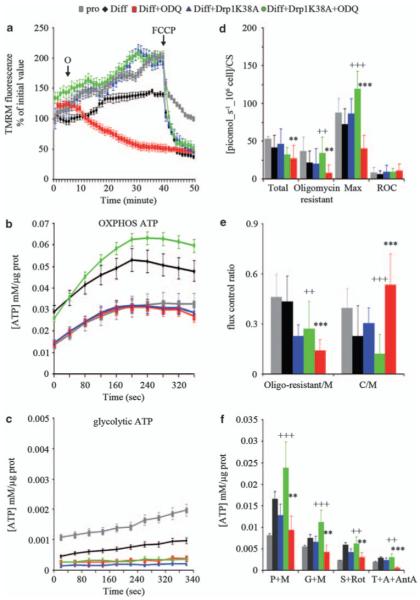

Figure 7.

The bioenergetic consequences of regulation of fission by NO and cGMP. Myogenic precursor cells were transfected with pEYFP-N1 or pEYFP-N1-Drp1 K38A, differentiated (diff) or allowed to proliferate (pro) for 6 h, and treated as specified. (a) The cells were loaded with the mitochondrial potentiometric dye TMRM and the mitochondrial membrane potential was measured 1 h after treatment with the vehicle (C) or ODQ. The arrows indicate addition of oligomycin (O; 1 μg/ml) and FCCP (4 μM). (b, c) The cells were loaded with luciferin-luciferase and the ATP generated through oxidative phosphorylation (b) or glycolysis (c) was measured after addition of the vehicle or ODQ. (d, e) Respiratory function was measured using a high-sensitivity respirometer. The values shown are for total, oligomycin-resistant, maximal (uncoupled) and residual oxygen consumption (ROC), as well as for the ratio of oligomycin-resistant to maximal (oligomycin resistant/M) and coupled (total minus oligomycin resistant) to maximal (C/M). (f) Activity of the mitochondrial respiratory complexes measured as in panel a assessing ATP generation in cells respiring on pyruvate–malate (P + M) or glutamate–malate (G + M) (complex-I), succinate–rotenone (S + Rot) (complex-II) TMPD–ascorbate–antimycin-A (T + A + AntA) (complex-IV). The panels show values ± S.E.M. (n = 4). The double (P<0.01) and triple (P<0.001) asterisks, and the crosses show statistical probability versus control and ODQ, respectively