Abstract

A 52-year-old woman experienced sudden onset of double vision due to a right abducens nerve palsy and was diagnosed as having a pituitary macroadenoma that invaded into the right cavernous sinus. Otherwise, she was asymptomatic despite marked elevation of ACTH (293 pg/ml) and cortisol (24.6 μg/dl) levels. The patient underwent transsphenoidal surgery followed by γ-knife radiosurgery (GKR), which healed the diplopia and ameliorated the hypercortisolemia. The excised tumor was diffusely stained for ACTH with a high (15%) Ki-67 labeling index. Early tumor recurrence occurred twice thereafter, producing right lower cranial nerve palsies with petrosal bone destruction at 8 months and an ipsilateral oculomotor nerve palsy at 12 months after GKR; all palsies resolved completely with the second and third GKRs. Hypercortisolemia worsened rapidly soon after the third GKR, and the patient developed marked weight gain, hypokalemia, and hypertension. Multiple liver lesions were incidentally detected with computer tomography and identified as metastatic pituitary tumor on immunohistochemistry. An ACTH-producing adenoma should be followed carefully for early recurrence and/or metastatic spread when the tumor is an invasive macroadenoma with a high proliferation marker level. The unique aggressive behavior and high potential for malignant transformation of this case are discussed.

Keywords: Pituitary carcinoma, Corticotroph carcinoma, Cushing's disease, γ-Knife radiosurgery

Introduction

Pituitary carcinoma is a rare disorder accounting for 0.1–0.5% of pituitary adenomas [1–4]. It is believed that pituitary carcinomas arise from the transformation of benign invasive macroadenomas [1–4], and the process of this transformation takes place slowly [1]. A large majority of pituitary carcinomas preserves a capacity for producing anterior pituitary hormones [1–4], most notably ACTH and prolactin. However, a definite distinction between pituitary carcinoma and adenoma is impossible on the basis of endocrinological, neuroradiological, and histological criteria. The presence of CNS and/or distant metastases is a prerequisite to establishing the diagnosis of this clinical entity [1–4]. The most common is corticotroph carcinoma, representing 42% of pituitary carcinomas [1–4], and 53 cases of corticotroph carcinoma have been described in the English literature so far [5–45]. At the time of diagnosis, 32 (60%) of the 53 cases presented with symptoms and signs of chronic hypercortisolemia characteristic of Cushing's disease [5–9, 12–18, 20–22, 27–32, 34, 35, 38, 39, 43], while 15 (28%) of the 53 cases developed these features 6 months to 12 years after an initial presentation as a pituitary mass compressing the surrounding tissues [10, 11, 19, 23–26, 33, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45]. Although very rarely, silent corticotroph carcinoma has also been recognized by the presence of metastatic lesions in the absence of clinical features associated with chronic hypercortisolemia [27, 41]. A case of corticotroph carcinoma, which displayed aggressive behavior resulting in multiple cranial nerve palsies, invasive petrosal bone destruction, and liver metastasis, is reported. This carcinoma presented initially as an invasive macroadenoma causing double vision and asymptomatic Cushing's disease, despite active hormone production.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old Japanese woman suddenly developed double vision on the way to her office and was referred to our university hospital by an ophthalmologist. She gained 10 kg in weight after menopause at the age of 50 years. On physical examination, the patient's height was 151 cm, and her weight was 63.5 kg, with a body mass index of 27.8 kg/m2. Blood pressure was 120/78 mmHg. The patient presented with no signs indicative of Cushing's syndrome, such as moon face, truncal obesity, buffalo hump, purple striae cutis, skin atrophy, or hirsutism. Neurological examination was unremarkable except for a right abducens nerve palsy. Past and family histories were unremarkable. She had a history of two normal deliveries at ages 26 and 28 years. Routine blood tests revealed no abnormalities in serum electrolytes, lipid profile, or glucose level.

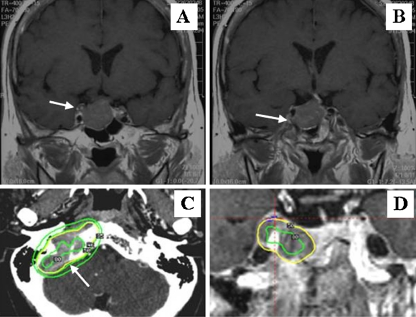

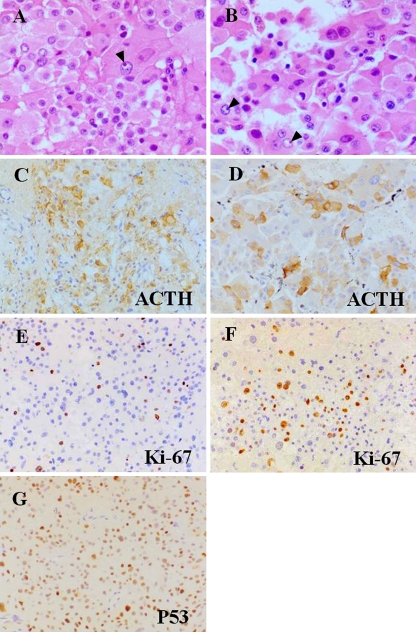

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a pituitary macroadenoma (height 22 mm; width 25 mm; depth 21 mm) that extended suprasellarly compressing the optic chiasm, infrasellarly into the sphenoid sinus, and laterally invading into the right cavernous sinus (Fig. 1a and b). On gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted coronal images, tumoral invasion into the right cavernous sinus was evident at its inferior portion along the inferior arterial wall of the intracavernous internal carotid artery (ICA; Fig. 1b) and at its middle portion through a space between the intra- and supracavernous ICAs (Fig. 1a). Goldman's visual field test was unremarkable. Endocrine investigation with the use of the IRMA kit (Mitsubishi Chemical Yatron, Tokyo, Japan) for ACTH and the TFB RIA kit (IMMUNOTEC, Prague, Czech Republic) for cortisol measurement revealed a concomitant elevation of morning ACTH (293 pg/ml; normal range, 7.4–55.7 pg/ml) and cortisol (24.6 μg/dl; normal range, 4.0–18.3 μg/dl) levels in blood and a complete loss of the diurnal change in both hormones (Table 1). Both elevated ACTH and cortisol levels did not respond to an intravenous injection of a 100-μg dose of human corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH; Sumitomo Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Osaka, Japan) or to orally administered low-dose (1 mg) or high-dose (8 mg) dexamethasone sodium phosphate in an overnight suppression test (Table 1). For the hormonal systems other than the ACTH-cortisol axis, growth hormone response to L-arginine hydrochloride (30 g) infusion was impaired, with a peak value of 0.12 μg/L (normal range, >3.0 μg/L). Basal gonadotropins were diminished below normal postmenopausal levels, while baseline prolactin and thyroid function were normal. The search for mass lesions producing ACTH ectopically within the thoracic and abdominal cavities with computed tomography (CT) was negative. The patient's double vision worsened progressively, and the patient underwent transsphenoidal surgery 8 days after the first visit. Histologically, the excised specimens were typical pituitary adenoma on hematoxylin–eosin staining (Fig. 2a) and were diffusely immunostained with mouse monoclonal anti-human ACTH antibody (Dako UK Ltd, Cambridgeshire, UK; Fig. 2c), consistent with ACTH-producing adenoma. The adenoma showed strong nuclear pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, and enlarged nucleoli (Fig. 2a), but it did not exhibit Crooke's hyaline change in the cytoplasm, a histological feature characteristic of Crooke cell adenoma. Mitotic figures were not observed. Up to 15% of tumor cells were positively stained for a proliferation marker, Ki-67 antigen, with mouse monoclonal anti-human MIB-1 antibody (Dako UK Ltd.; Fig. 2e).

Fig. 1.

Radiographic presentation of a pituitary invasive macroadenoma in a patient who presented with multiple cranial nerve palsies at different stages. Upper two films are conventional gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted 3-mm coronal slices (a, b), 6 mm apart in an anterior to posterior direction, at initial presentation with a right abducens nerve palsy. Arrows indicate cavernous sinus invasion. Lower two images are axial (c) and coronal (d) images of contrast-enhanced, 1-mm slices of bone CT at the time of lower cranial nerve palsies (c) and T1-weighted, 2-mm slices of high-resolution MRI at the time of a right oculomotor nerve palsy (d), both obtained under stereotactic conditions [46]. The recurrence occurred twice within the right cavernous sinus but not within the sella: at the first recurrence the tumor destructively invades the petrosal bone and has destroyed the jugular foramen (arrow) (c), and at the second, the tumor is seen to have recurred at the superior–posterior portion of the cavernous sinus (d). Color line-circled areas indicate the area irradiated with the same dose of GKR; the outer area was irradiated at a lower dosage

Table 1.

ACTH and cortisol measurement

| Diurnal change | Overnight dexamethasone suppression test | Human corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of day (h) | Dose | Time (min) | ||||||

| 8:00 | 23:00 | 1 mg | 8 mg | 0 | 30 | 60 | 90 | |

| ACTH (pg/ml) | 293 | 307 | 307 | 258 | 270 | 321 | 310 | |

| Cortisol (μg/dl) | 24.6 | 36.2 | 35.8 | 29.0 | 26.2 | 30.9 | 30.2 | |

Fig. 2.

Photomicrographs of the histological and immunohistochemical features of the primary pituitary tumor and the metastasized liver tumor. Pituitary tumor: a, c, e, and g; liver tumor: b, d, and f. Both pituitary and liver tumors show nuclear pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, and enlarged nucleoli (arrow heads) on hematoxylin–eosin staining, but neither tumor shows mitotic figures (a, b). There is diffuse cytoplasmic ACTH immunostaining in both tumors (c, d). Numerous tumor cell nuclei are positive for Ki-67, and the proportion of cells with positive Ki-67 staining accounts for 15% and 35% of the primary (e) and metastasized (f) tumor cells, respectively. Immunoreactive nuclear protein p53 examined in the primary pituitary tumor is stained in almost all cells (g). Original magnification ×400 (a, b), ×200 (c–g)

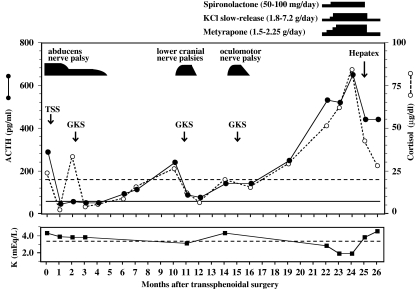

Following the transsphenoidal surgery, morning ACTH decreased to 47.9 pg/ml, accompanied by a decline in cortisol to 2.9–4.5 μg/dl (Fig. 3). In an overnight dexamethasone suppression test, however, serum cortisol was not suppressed to a normal level of <1.0 μg/dl with the high 8-mg dose. There was residual tumor in the right cavernous sinus on MRI. The abducens nerve palsy remained, though improved, leaving a moderate degree of double vision with lateral gaze to the right. Two months postoperatively, the patient was treated with γ-knife radiosurgery (GKR; marginal dose, 25 Gy; maximum dose, 50 Gy) using the Leksell Gamma Knife Model C with automatic positioning system (Elekta Instruments AB, Stockholm, Sweden) [46], which ameliorated diplopia completely by 3 months (Fig. 3). Eight months after GKR, ACTH and cortisol increased to 244 pg/ml and 26.9 μg/dl, respectively, and the patient developed a swallowing disturbance and hoarseness due to the lower cranial nerve palsies on the right side. Recurrence of the tumor was detected with bone CT (Fig. 1c) and high-resolution MRI within the right cavernous sinus at a site not previously irradiated but not within the sella. The recurrent tumor invaded destructively into the whole right petrosal bone and destroyed the jugular foramen (Fig. 1c). One month later, the second GKR (marginal dose, 15 Gy; maximum dose, 30 Gy) was carried out, resulting in complete disappearance of the lower cranial nerve palsies within 1 month and normalization of the cortisol but not the ACTH level (Fig. 3). Three months after the second GKR, ACTH and cortisol rose to 146 pg/ml and 20.5 μg/dl, respectively, and the patient again developed double vision, but this time with left lateral gaze due to the right oculomotor palsy. Recurrence of the tumor was again identified with MRI in the superior–posterior part of the right cavernous sinus (Fig. 1d), and 1 month after the appearance of double vision, the patient received the third GKR (marginal dose, 15 Gy; maximum dose, 30 Gy). The diplopia resolved completely within 1 month, and cortisol declined to an upper normal level of 16.1 μg/dl, but the elevated ACTH remained unchanged (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Clinical course as a function of time (months) after transsphenoidal surgery. Upper panel shows sequential change in blood ACTH and cortisol levels along with the timing (arrows) of therapeutic interventions that included transsphenoidal surgery (TSS), γ-knife radiotherapy (GKR), and partial right-lobe hepatectomy (Hepatex). The occurrence and resolution of cranial nerve palsies are shown by black bars, in which the width indicates the duration of palsy and the height indicates its severity. Broken and straight lines indicate the upper normal limit of cortisol (18.3 μg/dl) and ACTH (55.7 pg/ml), respectively. Shown over the upper panel are medications with daily dose in parentheses and their duration of use and dosage in black bars. Lower panel shows the same time course for serum potassium concentration with a broken line indicating the lower limit of normal (3.4 mEq/L)

Four months after the third GKR, both ACTH and cortisol began to rise rapidly, and 3 months later, they reached unusually high levels of 534 pg/ml and 52.0 μg/dl, respectively (Fig. 3). The patient's condition deteriorated, accompanied by rapid weight gain (7 kg), generalized skin pigmentation, severe hypokalemia (2.8 mEq/L), and hypertension (170/110 mmHg), all of which were uncontrollable with administration of spironolactone (50–100 mg/day) and metyrapone (1.5–2.25 g/day) and supplementation with slow-release potassium chloride (1.8–7.2 g/day; Fig. 3). Because ACTH and cortisol levels continued to increase, reaching extremely high levels of 654 pg/ml and 84.7 μg/dl, respectively (Fig. 3), bilateral adrenalectomy was planned as a therapeutic option. Abdominal CT at 24 months postoperatively to evaluate the status of adrenal hypertrophy identified multiple space-occupying lesions in the liver. Percutaneous needle biopsy gave negative results; only necrotic tissues were obtained. The patient underwent partial right-lobe hepatectomy [47], which removed all hepatic lesions and led to reduction of serum cortisol to 25.9–28.8 μg/dl and normalization of hypokalemia (Fig. 3). The excised hepatic lesions were histologically very similar to the in situ pituitary adenoma in terms of nuclear pleomorphism, increased nuclear chromatin, and prominent nucleoli on hematoxylin–eosin staining (Fig. 2b). On immunohistochemistry, the liver lesions were positive for ACTH (Fig. 2d) and showed a remarkably high Ki-67 labeling index (Fig. 2f) with a value (35%) approximately 2.4 times higher than that (15%) of the primary tumor. In addition, the in situ adenoma retrospectively immunostained with monoclonal mouse antibody to p53 protein (Dako UK Ltd) was strikingly positive (Fig. 2g). Following abdominal surgery, both the hypertension and hypokalemia became medically controllable, and the patient's condition was improving. Two months later, the patient died of septic shock of unknown etiology.

Discussion

Pituitary carcinoma cannot be diagnosed before it develops metastatic spread. The metastasis usually takes place within the CNS to the cerebral cortex, cerebellum or cerebellopontine angle, brainstem, and spinal cord, or outside the CNS to the liver, lymph nodes, bone, lung, and other tissues [1–4]. In the absence of metastasis, it seems necessary to attempt screening for those pituitary tumors that might have an aggressive potential to transform into carcinomas, although there is no practical clinical guideline for their screening at present.

In 1997, Pemicone et al. classified adenohypophysial tumors with respect to their aggressive potential and described seven tumor characteristics required for pituitary carcinoma [27]. The present case fulfilled all of the characteristics that they described except for the presence of mitosis: high Ki-67 immunoreactivity (15%), positive p53 immunoreactivity, macroadenoma tumor size (2 cm), gross invasion (proven by surgery), metastasis (liver), and high blood hormone levels (ACTH and cortisol). In 2004, the WHO introduced for pituitary tumors a new adenoma entity termed atypical adenoma, which was designated as an invasive tumor that exhibits an elevated mitotic index, a Ki-67 labeling index greater than >3%, and extensive nuclear staining for p53 immunoreactivity [48, 49]. This definition denotes an aggressive potential for atypical adenoma and the possibility of its future malignant transformation. Atypical adenoma differs from carcinoma only in the lack of metastasis. In keeping with the WHO classification in 2004, Kaltsas et al. proposed in 2005 that atypical tumors and those with a Ki-67 labeling index greater than 10%, regardless of p53 immunostaining, should be followed for early recurrence and/or development of metastases [2]. The pituitary tumor of the present patient fulfills the definition of the atypical adenoma introduced by the WHO, except for the presence of mitosis, and is consistent with the adenomas with a very high Ki-67 labeling index described by Kaltsas. Although there was no mitosis in either the primary or metastasized tumor in the present patient, it has been reported that mitoses were not demonstrated in all pituitary tumors, i.e., positive in 21.4% of invasive pituitary adenomas and 66.7% of pituitary carcinomas [50]. Nonetheless, this cannot explain why the primary adenoma cells did not show mitosis despite expressing Ki-67 immunoreactivity in a very high proportion. The cell cycle-specific Ki-67 antigen may not always reflect all of the proliferating abilities of individual adenomas that are turning over at different rates. Otherwise, mitoses might have been obscured, though present, by tissue processing or technical artifacts.

The latency period from the diagnosis of pituitary tumor to the demonstration of metastasis varied considerably among patients with corticotroph carcinomas [5–45], which probably reflects the difference in the speed at which individual pituitary adenomas transform into carcinoma. In the 53 reported patients with corticotroph carcinomas [5–45], the mean (±SE) latency period that we calculated was 93 ± 10 months (range, 3–360 months). The latency period of the present patient was 24 months, which in the order of latency length, was ranked as the fourth shortest. No doubt, the latency period would have shortened if abdominal CT, which detected hepatic metastases, had been performed at an earlier stage. Such clinically rapid progression of the disease, together with twice-repeated early recurrence within the cavernous sinus, is highly suggestive of an aggressive nature of the primary tumor from the beginning of its clinical manifestation.

The aggressive, even malignant, nature of the tumor might be supported by its high radiosensitivity, as evidenced by rapid resolution of cranial nerve palsies within 1–3 months after GKR. Three additional, unique behaviors of the present tumor became evident on neurological and radiological examinations. The first was a transient cystic enlargement of the irradiated residual tumor that was incidentally recognized on MRI 1 month after the first GKR. The second was the occurrence of the lower cranial nerve palsies that caused swallowing difficulty and a husky voice, and the third was destructive bone invasion involving the unilateral whole petrosal bone, which was detected on bone CT at the time of the lower cranial nerve palsies. We have never observed any of these findings in a series of several hundreds of pituitary adenoma patients whom we treated with GKR. There is no description on clinical features of atypical adenoma because it was defined as a pathological, but not clinical, entity intermediate between adenoma and carcinoma. The present tumor pathologically accords well with atypical adenoma except absence of mitosis, and hence its unusual behaviors associated with repeated local recurrence within the cavernous sinus could represent some clinical features of atypical adenoma. It is likely that the patient's tumor, which initially manifested as a clinically invasive macroadenoma or pathologically as an atypical adenoma, subsequently underwent malignant transformation presumably triggered by the surgery and/or irradiation, a main mechanism currently postulated to underlie the development of pituitary carcinoma (1–4).

The reason for initial lack of glucocorticoid excess symptoms may require some explanation. It might in part be due to partial cortisol resistance of unknown etiology, because the patient did not develop such hypercortisolemic signs/symptoms as systemic pigmentation and hypertension with hypokalemia until the last few months before death, at which time serum cortisol increased to an extraordinarily high level in parallel with ACTH. It is unlikely that the patient's adenoma secreted a biologically inactive, C-terminally extended, “big” ACTH [51]. First, the IRMA used for our ACTH measurements does not recognize this high-molecular-weight form of ACTH-related peptide. Second, a closely parallel change in ACTH and cortisol throughout almost the entire clinical course favors the view of tumor-secreted ACTH as a biologically active peptide.

Consistent with the present patient, a substantial proportion of previously reported patients with corticotroph carcinoma did not present initially with Cushing's disease. Of the 53 reported patients, including 34 women and 19 men, only 32 subjects were diagnosed as having Cushing' syndrome or disease at initial presentation [5–9, 12–18, 20–22, 27–32, 34, 35, 38, 39, 43]. The remaining 21 cases were endocrinologically asymptomatic, except for one case of galactorrhea–amenorrhea syndrome [25], and presented with the pituitary mass compressing the adjacent tissues [10, 11, 19, 23, 24, 26, 27, 33, 36, 37, 40–42, 44, 45]: visual disturbance in 13 cases, headache in one case, and visual impairment plus headache in five cases (symptoms not described in one case [39]). These 21 hormonally asymptomatic tumors, which were initially diagnosed as non-functioning adenomas, can be divided into two subgroups on the basis of the subsequent clinical course. One subgroup consisted of 15 adenomas that developed characteristic features of Cushing's disease 73 ± 12 months (range, 6–144 months) after initial diagnosis [10, 11, 19, 23–26, 33, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44, 45]. Of these 15 adenomas, only five tumors underwent initial immunohistochemical examination, and all were positive for ACTH, indicating that these 5 adenomas were silent corticotroph adenomas at the initial presentation. Notably, 12 of the 15 adenomas metastasized within 1–2 years after manifesting as Cushing's disease, which suggests the possibility that these metastasized adenomas had already undergone malignant transformation at the time of their clinical manifestation as Cushing's disease. The other subgroup consisted of the remaining six of the 21 adenomas that were all initially diagnosed as silent corticotroph adenoma with ACTH immunostaining and continued to be clinically silent until they caused systemic or craniospinal metastasis [27, 41].

It is likely that marginally hypercortisolemic or even eucortisolemic but endocrinologically abnormal subjects have been mixed in with these initially asymptomatic patients, because subjects with Cushing's disease often have upper normal levels of baseline ACTH and/or cortisol in blood. This is in contrast with prolactinomas, in which blood prolactin levels increase proportionally with the size of tumors, and macroadenomas usually have prolactin values more than ten times higher than the normal upper limit, thereby not requiring any dynamic test for diagnosis [1–4, 52]. In clinically asymptomatic or subclinical Cushing's disease, however, it is often difficult to make an accurate diagnosis only with baseline cortisol and/or ACTH levels without measuring 24-h urinary free cortisol output or performing appropriate diagnostic tests, such as an overnight dexamethasone suppression test to demonstrate the abnormal glucocorticoid feedback regulation or determination of the morning and midnight cortisol levels to identify the abnormal diurnal rhythm of the ACTH-cortisol axis. The use of such diagnostic tests in patients with invasive macroadenoma will decrease the chance of misdiagnosing asymptomatic patients with Cushing's disease as having a non-functioning pituitary adenoma.

In conclusion, this is the first case of pituitary carcinoma in our university hospital over the last 30 years, which is in accordance with the rarity of this clinical entity. The patient's tumor differed from common invasive macroadenomas, clinically with repeated early recurrence and immunohistochemically with an extraordinarily high Ki-67 labeling index. Rapid aggressive progression of the disease from initial presentation suggests that the patient's pituitary tumor might have emerged de novo as a corticotropinoma with high potential for malignant transformation. In our clinical experience, non-functioning adenomas, the majority of which is represented by gonadotropin-producing adenomas, rarely exhibit a high degree of cavernous sinus invasion, while often showing prominent suprasellar extension. “Non-functioning” adenomas, if they exhibit marked parasellar invasion, should be screened for adenomas of non-gonadotroph lineage. It is important to emphasize that all patients with invasive macroadenoma should be screened for Cushing's disease with an appropriate diagnostic test even if they are hormonally asymptomatic or eucortisolemic, and if they indeed represent Cushing's macroadenoma, they should be carefully followed for the future development of corticotroph carcinoma.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. K. Kovacs (Toronto, Canada) for his comments and Ms. R. Makino for her excellent secretarial assistance.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Scheithauer BW, Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Kovacs KT, Young WF, Jr, Lloyd RV. Pituitary carcinoma: a clinicopathological review. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1066–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaltsas GA, Nomikos P, Kontogeorgos G, Buchfelder M, Grossman AB. Clinical review: diagnosis and management of pituitary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3089–3099. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ragel BT, Couldwell WT. Pituitary carcinoma: a review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16:1–9. doi: 10.3171/foc.2004.16.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaltsas GA, Grossman AB. Malignant pituitary tumours. Pituitary. 1998;1:69–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1009975009924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen H, Dible JH. Pituitary basophilism associated with a basophil carcinoma of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Brain. 1936;59:395–407. doi: 10.1093/brain/59.4.395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forbes W. Carcinoma of the pituitary gland with metastases to the liver in a case of Cushing's syndrome. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1947;59:137–144. doi: 10.1002/path.1700590115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feiring EH, Davidoff LM, Zimmermann HM. Primary carcinoma of the pituitary. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1953;12:205–233. doi: 10.1097/00005072-195307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheldon WH, Golden A, Bondy PK. Cushing's syndrome produced by a pituitary basophil carcinoma with hepatic metastases. Am J Med. 1954;17:134–142. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salassa RM, Kearns TP, Kernohan JW, Sprague RG, MacCarty CS. Pituitary tumors in patients with Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1959;19:1523–1539. doi: 10.1210/jcem-19-12-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholz DA, Gastineau CF, Harrison EG. Cushing's syndrome with malignant chromophobe tumor of the pituitary and extracranial metastasis: report of a case. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1962;37:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Queiroz Lde S, Facure NO, Facure JJ, Modesto NP, Lopes de Faria J. Pituitary carcinoma with liver metastases and Cushing syndrome. Report of a case. Arch Pathol. 1975;99:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore TJ, Dluhy RG, Williams GH, Gain JP. Nelson's syndrome: frequency, prognosis and effects of prior pituitary radiation. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:731–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-6-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser FE, Orth DN, Mukai K, Oppenheimer JH. A pituitary parasellar tumor with extracranial metastases and high, partially suppressible levels of adrenocorticotropin and related peptides. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:649–653. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-3-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zafar MS, Mellinger RC, Chason JL. Cushing's disease due to pituitary carcinoma. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1984;32:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gatti G, Limone P. ACTH-producing hypophyseal carcinoma monitored by computed tomography. Diagn Imag Clin Med. 1984;53:292–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papotti M, Limone P, Riva C, Gatti G, Bussolati G. Malignant evolution of an ACTH-producing pituitary tumor treated with intrasellar. Case report and review of the literature. implantation of 90Y. Appl Pathol. 1984;2:10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casson IF, Walker BA, Hipkin LJ, Davis JC, Buxton PH, Jeffreys RV. An intrasellar pituitary tumour producing metastases in liver, bone and lymph glands and demonstration of ACTH in the metastatic deposits. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1986;111:300–304. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1110300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrilove JL, Anderson PJ, Halmi NS. Pituitary pro-opiomelanocortin-cell carcinoma occurring in conjunction with a glioblastoma in a patient with Cushing's disease and subsequent Nelson's syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1986;25:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1986.tb01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawata H, Higuchi K, Ikuyama S, Kato K, Ibayashi H, Mimura K, Sueishi K, Zingami H, Imura H. Corticotropin-releasing hormone- and adenocorticotropin-producing pituitary carcinoma with metastases to the liver and lung in a patient with Cushing's disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:1068–1073. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-4-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levesque H, Freger P, Gancel A, Tayot J, Courtois H. Pituitary carcinoma of pituitary gland with Cushing's syndrome and metastases. Apropos of a case with review of the literature. Rev Méd Interne. 1991;12:209–212. doi: 10.1016/S0248-8663(05)83174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonner D, Belding P, Moore SA, Schlechte JA. Intracranial dissemination of an ACTH secreting pituitary neoplasm–a case report and review of the literature. J Endocrinol Investig. 1992;15:387–391. doi: 10.1007/BF03348759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouhara H, Tatekawa T, Koga M, Hiraga S, Arita N, Mori H, Sato B. Intracranial and intraspinal dissemination of an ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor. Endocrinol Jpn. 1992;39:177–184. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.39.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giordana MT, Cavalla P, Allegranza A, Pollo B. Intracranial dissemination of pituitary adenoma. Case report and review of the literature. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1994;15:195–200. doi: 10.1007/BF02339323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bates AS, Buckley N, Boggild MD, Bicknell EJ, Perrett CW, Broome JC, Clayton RN. Clinical and genetic changes in a case of a Cushing's carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1995;42:663–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost AR, Tenner S, Tenner M, Rollhauser C, Tabbara SO. ACTH-producing pituitary carcinoma presenting as the cauda equina syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Della Casa S, Corsello SM, Satta MA, Rota CA, Putignano P, Vangell V, Colosimo C, Anile C, Barbarino A. Intracranial and spinal dissemination of an ACTH secreting pituitary neoplasia. Case report and review of the literature. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 1997;58:503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pernicone PJ, Scheithauer BW, Sebo TJ, Kovacs KT, Horvath E, Young WF, Jr, Lloyd RV, Davis DH, Guthrie BL, Schoene WC. Pituitary carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Cancer. 1997;79:804–812. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<804::AID-CNCR18>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrao AF, Sobrinho LG, Pedro-Oliveira, Bugalho MJ, Boavida JM, Raposo JF, Loureiro M, Limbert E, Costa I, Antunes JL. ACTH-producing carcinoma of the pituitary with haematogenic metastases. Eur J Endocrinol. 1997;137:176–180. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1370176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lormeau B, Miossec P, Sibony M, Valensi P, Attali JR. Adrenocorticotropin-producing pituitary carcinoma with liver metastasis. J Endocrinol Investig. 1997;20:230–236. doi: 10.1007/BF03346909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinton DR, Hahn JA, Weiss MH, Couldwell WT. Loss of Rb expression in an ACTH-secreting pituitary carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 1998;126:209–214. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaltsas GA, Mukherjee JJ, Plowman PN, Monson JP, Grossman AB, Besser GM. The role of cytotoxic chemotherapy in the management of aggressive and malignant pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:4233–4238. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.12.4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kemink SA, Wesseling P, Pieters GF, Verhofstad AA, Hermus AR, Smals AG. Progression of a Nelson's adenoma to pituitary carcinoma; a case report and review of the literature. J Endocrinol Investig. 1999;22:70–75. doi: 10.1007/BF03345482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masuda T, Akasaka Y, Ishikawa Y, Ishii T, Isshiki I, Imafuku T, Ogihara T, Miyazaki H, Asuwa N. An ACTH-producing pituitary carcinoma developing Cushing's disease. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:183–187. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(99)80032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed M, Kanaan I, Alarifi A, Ba-Essa E, Saleem M, Tulbah A, McArthur P, Hessler R. ACTH-producing pituitary cancer: experience at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre. Pituitary. 2000;3:105–112. doi: 10.1023/A:1009957824871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zahedi A, Booth GL, Smyth HS, Farrell WE, Clayton RN, Asa SL, Ezzat S. Distinct clonal composition of primary and metastatic adrenocorticotrophic hormone-producing pituitary carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:549–556. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holthouse DJ, Robbins PD, Kahler R, Knuckey N, Pullan P. Corticotroph pituitary carcinoma: case report and literature review. Endocr Pathol. 2001;12:329–341. doi: 10.1385/EP:12:3:329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki K, Morii K, Nakamura J, Kaneko S, Ukisu J, Hanyu O, Nakagawa O, Aizawa Y. Adenocorticotropin-producing pituitary carcinoma with metastasis to the liver in a patient with Cushing's disease. Endocr J. 2002;49:153–158. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.49.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landman RE, Horwith M, Peterson RE, Khandji AG, Wardlaw SL. Long-term survival with ACTH-secreting carcinoma of the pituitary: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3084–3089. doi: 10.1210/jc.87.7.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaffey TA, Scheithauer BW, Lloyd RV, Burger PC, Robbins P, Fereidooni F, Horvath E, Kovacs K, Kuroki T, Young WF, Sebo TJ, Riehle DL, Belzberg AJ. Corticotroph carcinoma of the pituitary: a clinicopathological study. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:352–360. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.2.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrell WE, Coll AP, Clayton RN, Harris PE. Corticotroph carcinoma presenting as silent corticotroph adenoma. Pituitary. 2003;6:41–47. doi: 10.1023/A:1026233927714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roncaroli F, Scheithauer BW, Young WF, Horvath E, Kovacs K, Kros JM, Al-Sarraj S, Lloyd RV, Faustini-Fustini M. Silent corticotroph carcinoma of the adenohypophysis: a report of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:477–486. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tysome J, Gnanaligham KK, Chopra I, Mendoza N. Intradural metastatic spinal cord compression from ACTH-secreting pituitary carcinoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2004;146:1251–2154. doi: 10.1007/s00701-004-0350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ceyhan K, Yagmurlu B, Dogan BE, Erdogan N, Bulut S, Erekul S. Cytopathologic features of pituitary carcinoma with cervical vertebral bone metastasis: a case report. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:225–230. doi: 10.1159/000325938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown R, Wollman R, Weiss R. Transformation of a pituitary macroadenoma into a corticotropin-secreting carcinoma over 16 years. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:463–471. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinchot SN, Sippel R, Chen H. ACTH-producing carcinoma of the pituitary with refractory Cushing's disease and hepatic metastases: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:39–45. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yomo S, Hayashi M, Chernov M, Tamura N, Izawa M, Okada Y, Hori T, Iseki H. Stereotactic radiosurgery of residual or recurrent craniopharyngioma: new treatment concept using Leksell gamma knife model C with automatic positioning system. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2009;87:360–367. doi: 10.1159/000236370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto M, Arizumi S, Katagiri S, Kotera Y, Takahashi Y. The value of anatomical liver sectionectomy for patients with a solitary hepatocellular carcinoma from 2 to 5 cm in greatest diameter. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:585–588. doi: 10.1002/jso.21363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lloyd RV, Kovacs K, Young WF, Jr, Farrell WE, Asa SL, Trouillas J, Kontogeorgos G, Sano T, Scheithauer BW, Horvath E. Tumours of the pituitary. In: DeLellis RA, Lloyd RV, Heitz PU, Eng C, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of endocrine organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. pp. 10–47. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Shraim M, Asa SL. The 2004 World Health Organization classification of tumors: What is new? Acta Neuropathol. 2006;111:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pernicone PJ, Scheithauer BW. Invasive pituitary adenoma and pituitary carcinoma. In: Thapar K, Kovacs K, Scheithauer BW, Lloyd RV, editors. Diagnosis and management of pituitary tumors. Totawa: Humana Press; 2001. pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reincke M, Allolio B, Saeger W, Kaulen D, Winkelmann W. A pituitary adenoma secreting high molecular weight adrenocorticotropin without evidence of Cushing's disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:1296–1300. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-6-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ono M, Miki N, Amano K, Kawamata T, Seki T, Makino R, Takano K, Izumi S, Okada Y, Hori T. Individualized high-dose cabergoline therapy for hyperprolactinemic infertility in women with micro- and macroprolactinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2672–2679. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]