Abstract

Background

Chronically critically ill patients typically undergo an extended recovery after discharge from the intensive care unit, making involvement of family caregivers essential. Prior studies provide limited detail about specific ways this experience affects caregivers.

Objectives

To (1) describe lifestyle restrictions and distress among caregivers of chronically critically ill patients 1 and 6 months after discharge and (2) explore how caregivers’ lifestyle restrictions and distress differ according to patients’ and caregivers’ characteristics.

Methods

Sixty-nine chronically critically ill patients and their family caregivers completed follow-up at 1 and 6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit. Data were collected from medical records and survey via telephone or mail.

Results

Caregivers’ perceived lifestyle restrictions (Changes in Role Function) decreased from 1 month (mean [SD], 23.0 [8.3]) to 6 months (19.4 [8.6]) after discharge (P = .003), although patients’ problem behaviors and caregivers’ distress (8.9 [9.3] vs 7.9 [9.6], respectively; P = .32) did not change. Change in caregivers’ lifestyle restrictions differed by patients’ disposition (P = .02) and functional status (Health Assessment Questionnaire; P = .007). Caregiver’s lifestyle restrictions remained high when patients never returned home or never recovered their preadmission functional status. Caregivers reported the most restrictions in social life and personal recreation. Patients’ negative emotions and pain caused the most caregiver distress.

Conclusions

Caregivers of chronically critically ill patients perceived fewer lifestyle restrictions over time but reported no change in patients’ problem behaviors or distress. Lifestyle restrictions and distress remained high when patients never returned home or regained their preadmission functional status.

It is estimated that 50 million people in the United States provide care for a chronically ill, disabled, or aged family member or friend.1 For caregivers of persons with cancer and dementia, extensive evidence shows that negative psychological and behavioral consequences are common and may be linked to a decline in caregivers’ overall health.2,3 Caregivers of critically ill patients also experience high levels of stress. Recovery from critical illness may occur quickly or gradually over an extended period. The term chronically critically ill (CCI) is commonly used to describe persons who require an extended duration of mechanical ventilation and hospitalization after recovery from critical illness.4

Evidence from a variety of sources suggests that growing numbers of caregivers will face the need to support CCI patients after hospital discharge. Demand for critical care, including mechanical ventilation, is anticipated to increase sharply as the generation of “baby boomers” grows to 20% of the total US population by 2030.5 Currently, 5% to 20% of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) require mechanical ventilation for periods that can extend to weeks or months,6 and those percentages are expected to increase.7,8 It has been estimated that by 2020 more than 600 000 patients per year will require extended critical care support.9 Such patients encounter enormous difficulties, including psychoemotional stress, reduced physical and neurocognitive function, symptom burden, and frequent hospital readmissions.7,10,11 Concurrently, family caregivers must cope with financial, emotional, and physical stressors.12

In several prior studies,12–18 caregivers of CCI patients were surveyed about their psychological responses. Despite heterogeneous characteristics of patients (eg, severity of illness, days of mechanical ventilation) and follow-up intervals (2 to 23 months), findings uniformly included a high incidence of depression12–18 that was comparable to the incidence of depression in caregivers of the frail elderly and twice the incidence of depression in the general population. Douglas and Daly12 reported decreased physical health and increased risk of depression in caregivers of CCI patients that exceeded reports for other populations of patients who require long-term caregiving, such as patients with Alzheimer’s disease and patients with spinal cord injury. When patients remained institutionalized, family caregivers reported a higher incidence of depression and burden, more disruption in daily schedules, more health problems, and less family support.14,16 Depressive symptoms decreased over time,13,18 but remained higher than in the general population. Notably, in an analysis of a national data set comprising almost 300 000 cases, a significantly higher risk of death was reported in spouses of persons who received mechanical ventilation for 4 days or longer.19

Reports of prior studies13,16–18 have described the challenges encountered by caregivers of CCI patients. However, most did not identify the specific lifestyle restrictions, distress, or problem behaviors of patients that were of most concern. In an effort to identify ways to support caregivers of CCI patients, it may be helpful to explore longitudinal changes in caregiver response as influenced by changes in the characteristics of patients. It is also important to identify specific areas that cause caregivers to experience greater lifestyle restriction and distress. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe perceived lifestyle restrictions and distress among caregivers of CCI patients at 1 and 6 months after ICU discharge. We also explored how caregivers’ lifestyle restrictions and distress differed according to the characteristics of the patients and the caregivers.

Methods

Site and Sample

Caregiver and patient dyads were enrolled in the study after admission to a medical ICU of an academic medical center or an affiliated long-term acute care hospital in western Pennsylvania. The study was approved by the university’s institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all caregivers and patients before data collection. If the patient was unable to provide informed consent, proxy consent was provided by the patient’s legally authorized representative.

Eligibility criteria for caregivers were as follows: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) identified by the patient or family as “the individual primarily responsible for caring of the patient on an unpaid basis,” and (3) able to communicate in English. Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) admitted to an ICU, (3) receiving mechanical ventilation for at least 7 consecutive days, (4) living at home before this admission, and (5) undergoing daily weaning trials. Patients who were not living at home and/or had been dependent on mechanical ventilation before admission to the ICU were excluded because the intent was to focus on the acute impact of caregiving specifically due to CCI.

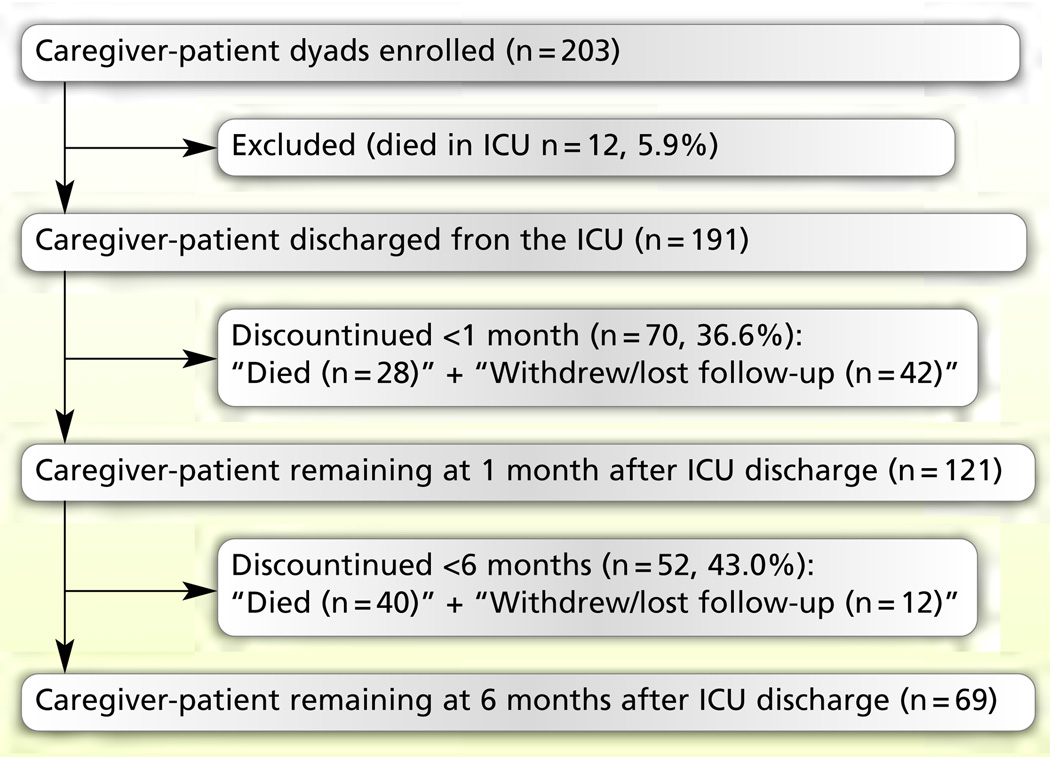

A total of 203 dyads were enrolled from August 2000 through July 2005. Twelve patients died while in the ICU. Of those discharged from the ICU (n=191), 68 patients (35.6%) died and 54 dyads (28.3%) either withdrew or were lost to follow-up, leaving a final sample of 69 dyads at 6 months after ICU discharge (Figure 1). The most common reason for withdrawal was “feeling overwhelmed.”

Figure 1. Subject enrollment and follow-up.

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Design and Procedure

A longitudinal survey design was used. Patients’ demographic and clinical data were obtained from medical records. Patients’ functional status was described by using caregiver recall (before ICU admission), observation (at ICU discharge), and caregiver report (at 1 and 6 months after ICU discharge). Caregivers were surveyed at 1 and at 6 months after ICU discharge to determine their perceived lifestyle restrictions and distress, patient’s disposition, and weaning status. In order to promote subject retention, the caregiver survey was conducted by mail or by telephone depending on the caregiver’s preference.

Instruments

A scale called Changes in Role Function (CRF) was used to measure caregivers’ perceived lifestyle restrictions. The CRF was a subscale from the Older Americans’ Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire, which was designed to assess changes in function, self-care, and service utilization20 and later modified to assess caregivers’ outcomes.21 This 11-item scale asked caregivers how much their personal and social activities were restricted, for example, caring for self and/or others, eating, sleeping, and recreation. Scores ranged from 1 (not restricted at all) to 4 (greatly restricted). The total score ranged from 11 to 44. Higher scores indicated more perceived restrictions. In a prior study16 in a similar population, the Cronbach α was 0.89. The Cronbach α in the present study was 0.93.

Caregiver distress was measured by using an 18-item subscale that included items modified from the Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist. That checklist was originally designed to measure caregivers’ assessments of memory problems, disruptive behaviors, and depressive symptoms among patients with dementia.22 The present study used a previously modified version that added items relevant to the CCI, such as sleeping, swallowing, pain, hearing, following directions, and self-care.23 An overall score for frequency of problem behaviors was generated by summing scores for reported behaviors. The total score ranged from 0 to 18. Higher scores indicated more behavioral problems. In a prior study16 in caregivers of patients receiving mechanical ventilation for 2 days or more, the Cronbach α was 0.73. The Cronbach α in the present study was 0.88.

The instrument also provided a score for caregiver distress by scoring the amount of distress caused by the problem behavior, using the scale 0 (not at all bothered or upset) to 4 (extremely upset). If a given behavior was not reported, a score of 0 was assigned. Higher scores indicated greater perceived distress. In a prior study16 with a similar caregiver population, the Cronbach α was 0.78. In the present study, the Cronbach α was 0.88.

The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) was used to assess patients’ functional status. The 20-item instrument included 8 categories: dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and outside activities. Each category included 2 or 3 items. For each item, the choice of response ranged from 0 (without any difficulty) to 3 (unable to do). Each category was scored by the highest score on any item in the category. The total score (range, 0–3) was calculated by summing scores from each category and dividing by the number of completed categories.24 Higher scores indicated poorer functional status. Test-retest correlations have ranged from 0.87 to 0.99.24 Correlations between scores obtained by using self-report or interview and task performance have ranged from 0.71 to 0.95.24,25 Construct/convergent validity, predictive validity, and sensitivity to change have been established in diverse settings.25 The HAQ score at ICU discharge has been a predictor of returning home at 6 months after ICU discharge in patients on mechanical ventilation for at least 7 days.26

Patient Characteristics

Severity of illness was measured at ICU admission by using the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scoring system.27 ICU length of stay was defined as total days in the ICU that were rounded to the nearest 24-hour period. Days of mechanical ventilation were defined as total days of mechanical ventilation in the ICU from the day of intubation and commencement of mechanical ventilation to the day of extubation and no requirement for mechanical ventilation, rounded to the nearest 24-hour period. Patients were also described in regard to their primary ICU admission diagnosis. Disposition, defined as returning home at each follow-up point, consisted of 3 categories: (1) returned home at 1 month, (2) returned home at 6 months, and (3) never returned home. Weaning status, defined as no requirement for mechanical ventilation, consisted of 4 categories: (1) weaned at 1 month, (2) weaned at 6 months, (3) never weaned, and (4) weaned at 1 month but returned to mechanical ventilation at 6 months. Patients who required mechanical ventilation, including noninvasive mechanical ventilation, for any part of the day were classified as not weaned.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed by using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Missing data analysis showed less than 5% of missing data at random. Mean substitution was used as an imputation strategy. Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation; categorical variables were reported as proportions. The Friedman χ2 was used to describe the change in HAQ scores from before ICU admission to 6 months after ICU discharge. Paired t tests were used to describe the change in caregivers’ perceived lifestyle restrictions and distress from 1 to 6 months after ICU discharge. Following paired t tests, Cohen’s d was used to report the effect sizes: 0.20 (small), 0.50 (moderate), and 0.80 (large).28 Frequencies were computed to explore areas reported as (1) most restricting caregivers’ lifestyle, (2) most frequently identified problem behaviors, and (3) behaviors that most distressed caregivers. Mixed analysis of variance was performed on caregivers’ lifestyle restrictions and distress as a function of time (1 and 6 months) and patient or caregiver characteristics. To describe main effects in variables with 3 or more levels, the Bonferroni test was used for pairwise comparison. The partial eta squared (partial η2) was used to report the effect sizes: 0.01 (small), 0.06 (moderate), and 0.14 (large).28–30 Weaning status was not included in the analysis because most patients (74%) were weaned from mechanical ventilation at 1 month after ICU discharge. Alpha was set at P < .05 (2-tailed) a priori.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Caregivers were predominantly white, female, a spouse or adult child, and 51 to 70 years of age (Table 1). Most caregivers were employed. Patients were mostly white and female with a median age of 58.5 years (Table 2). Respiratory problems comprised the most common admission diagnosis category. Patients had received mechanical ventilation for a median of 23.5 days in the ICU. At ICU discharge, 40 (58%) were weaned off of mechanical ventilation. No patient was directly discharged home from the ICU.

Table 1.

Caregiver demographics (N = 69)

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| < 30 | 2 (23) |

| 31 – 50 | 22 (32) |

| 51 – 70 | 32 (46) |

| >70 | 9 (13) |

| Unknown | 4 (6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 29 (42) |

| Female | 36 (52) |

| Unknown | 4 (6) |

| Race | |

| White | 63 (91) |

| African American | 6 (9) |

| Relationship | |

| Spouse | 38 (55) |

| Adult child | 15 (22) |

| Parent/guardian | 6 (9) |

| Sibling | 4 (6) |

| Other | 6 (9) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 41 (59) |

| Unemployed/retired | 25 (36) |

| Unknown | 3 (4) |

Table 2.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics (N = 69)

| Variable | Median (range) | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 58.5 (18.0–89.0) | |

| Sex, male | 28 (41) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 64 (93) | |

| African American | 5 (7) | |

| Admission diagnosis | ||

| Respiratory | 30 (43) | |

| Neurological | 10 (14) | |

| Cardiovascular | 8 (12) | |

| Sepsis | 6 (9) | |

| Trauma/surgical complications | 6 (9) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (6) | |

| Renal | 3 (4) | |

| Hemato-oncology | 1 (1) | |

| Others (overdose) | 1 (1) | |

| Days in intensive care unit (ICU) | 25.5 (7–92) | |

| Days of mechanical ventilation in ICU | 23.5 (7–92) | |

| Score on Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II On admission to ICU | 19 (7–43) | |

| Discharge disposition | ||

| Long-term acute care hospital | 29 (42) | |

| General hospital unit or skilled nursing facility | 39 (57) | |

| Other hospital ICU | 1 (1) | |

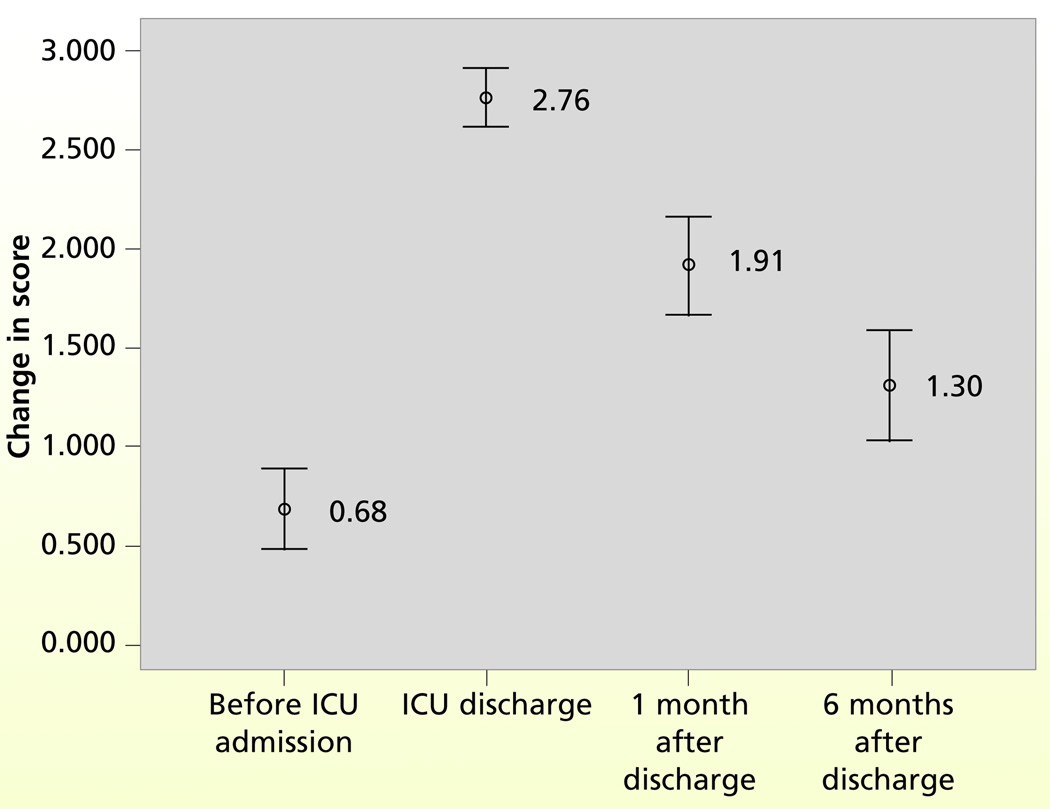

HAQ scores changed from the baseline to 6 months after ICU discharge (Friedman , n = 67, P <.001; Figure 2). The mean HAQ score was highest (worst functional status) at ICU discharge, when 81% of patients had a score of 3, the worst limitation. Functional status progressively improved over time. However, 64% had not recovered to their level before ICU admission by 6 months after ICU discharge (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Change in scores on the Health Assessment Questionnaire from before admission to 6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU) for patients who completed the 6 months follow-up. Higher scores indicate worse functional status. Numbers on the figure indicate the mean score and the lines indicate the 95% confidence interval at each data collection point.

Table 3.

Patients’ home-going status, weaning status, and functional status at 1 month and at 6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU; N = 69)

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Disposition | |

| Returned home at 1 month | 20 (29) |

| Returned home at 6 months | 36 (52) |

| Never returned home | 13 (19) |

| Weaning status | |

| Weaned from mechanical ventilation at 1 month | 51 (74) |

| Weaned from mechanical ventilation at 6 months | 9 (13) |

| Weaned at 1 month but returned to mechanical ventilation at 6 months | 1 (2) |

| Never weaned from mechanical ventilation | 2 (3) |

| Missing (1 month or 6 months) | 6 (9) |

| Functional statusa | |

| Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 1 month | 7 (10) |

| Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 6 months | 18 (26) |

| Never recovered to same level as before ICU admission | 44 (64) |

Functional status was measured by completing the Health Assessment Questionnaire.

Caregivers’ Lifestyle Restrictions and Caregiver Distress

Mean total scores for CRF decreased from 23.0 (SD, 8.3) measured at 1 month after ICU discharge to 19.4 (SD, 8.6) at 6 months after ICU discharge (paired t test, t = 3.123; P = .003; Cohen’s d = 0.97). At 1 month after ICU discharge, 75% of caregivers reported moderate or greater restrictions (scores ≥ 3) in visiting with friends. Moderate or greater restrictions in participating in hobbies and recreation were reported by 48% of caregivers (Table 4). For these 3 areas, at least 35% of caregivers continued to report moderate or greater restrictions at 6 months after ICU discharge.

Table 4.

Perceived lifestyle restrictions (N = 69)a

| Changes in Role Function scores |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month |

6 months |

|||||

| Characteristic | Mean | SD | No. (%) of item scores ≥ 3 |

Mean | SD | No. (%) of item scores ≥ 3 |

| Visiting with friends | 2.7 | 1.2 | 52 (75) | 2.1 | 1.1 | 24 (35) |

| Working on hobbies | 2.5 | 1.1 | 33 (48) | 2.1 | 1.2 | 25 (36) |

| Caregiver’s sports and recreation | 2.6 | 1.1 | 33 (48) | 2.1 | 1.2 | 25 (36) |

| Going shopping for self | 2.2 | 1.1 | 27 (39) | 1.7 | 1.0 | 16 (23) |

| Doing household chores | 2.1 | 1.0 | 24 (35) | 1.8 | 1.0 | 19 (28) |

| Caregiver’s sleeping habits | 2.0 | 1.0 | 25 (36) | 1.7 | 1.0 | 14 (20) |

| Caring for self | 1.9 | 1.0 | 16 (23) | 1.6 | 0.9 | 11 (16) |

| Caring for others (eg, spouse, children) | 1.9 | 1.0 | 19 (28) | 1.6 | 0.9 | 9 (13) |

| Caregiver’s eating habits | 1.8 | 0.9 | 15 (22) | 1.6 | 1.0 | 16 (23) |

| Going to work | 1.7 | 1.0 | 11 (16) | 1.5 | 0.8 | 7 (10) |

| Maintaining friendship | 1.7 | 0.9 | 14 (20) | 1.5 | 0.8 | 8 (12) |

| Total Changes in Role Function score | 23.0 | 8.3 | 19.4 | 8.6 | ||

Caregiver-perceived lifestyle restrictions at 1 month and at 6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit reflected by mean scores for each item and the percentage of caregivers who perceived moderate or great restriction (item score ≥3).

Caregiver distress measured at 1 month after ICU discharge (mean, 8.9; SD, 9.3) did not differ significantly from that at 6 months after ICU discharge (mean, 7.9; SD, 9.6; paired t test, t = 0.10, P =.32; Cohen’s d = 0.23). The number of caregiver-perceived patient problems at 1 month (mean, 6.2; SD, 4.5) did not differ significantly from the number measured at 6 months after ICU discharge (mean, 5.0; SD, 4.8; paired t test, t = 1.94, P = .06; Cohen’s d = 0.58). Although the overall proportion of caregivers who reported problem behaviors decreased at 6 months after ICU discharge, some behaviors were reported more frequently at 6 months: “Waking up others at night,” “Making comments about feeling like a failure or about not having any worthwhile accomplishment in life,” “Making comments about death of self or others,” “Having nightmares,” “Engaging in behaviors that are potentially dangerous to self or others” (Table 5).

Table 5.

Caregiver-perceived distress according to problem behavior of patient (N = 69)a

| Caregiver-perceived distress |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month |

6 months |

|||||||||

| Patient’s problem behavior | No. (%) of yes responses |

Mean | SD | No. (%) of item scores ≥ 2 |

No. (%) of yes responses |

Mean | SD | No. (%) of item scores ≥ 2 |

χ2 | P |

| Having difficulty in doing things for self | 47 (68) | 0.9 | 1.2 | 15 (22) | 25 (36) | 0.6 | 1.1 | 13 (19) | 4.6 | .03b |

| Being anxious or worried | 44 (64) | 1.0 | 1.1 | 19 (28) | 37 (54) | 0.8 | 1.1 | 19 (28) | 4.9 | .03b |

| Having pain or discomfort | 41 (59) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 24 (35) | 37 (54) | 1.0 | 1.4 | 20 (29) | 11. 9 | <.001b |

| Appearing sad or distressed | 36 (52) | 0.9 | 1.2 | 19 (28) | 29 (42) | 0.7 | 1.1 | 18 (26) | 11.3 | .001b |

| Arguing, irritable, or complaining | 30 (44) | 0.6 | 1.0 | 12 (17) | 22 (32) | 0.5 | 0.9 | 9 (13) | 5.3 | .02b |

| Having trouble falling asleep | 29 (42) | 0.5 | 0.8 | 11 (16) | 26 (38) | 0.5 | 0.9 | 9 (13) | 6.5 | .01b |

| Crying or tearful | 26 (38) | 0.7 | 1.2 | 16 (23) | 18 (26) | 0.5 | 1.1 | 13 (19) | 8.7 | .003b |

| Making comments about feeling worthless or being a burden to others | 25 (36) | 0.4 | 0.9 | 7 (10) | 21 (30) | 0.6 | 1.1 | 13 (19) | 16.2 | <.001b |

| Having difficulty understanding people | 22 (32) | 0.4 | 0.8 | 6 (9) | 13 (19) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 3 (4) | 0.3 | .57 |

| Having difficulty in swallowing | 21 (30) | 0.4 | 1.0 | 8 (12) | 16 (23) | 0.3 | 0.7 | 5 (7) | 14.4 | <.001b |

| Having problems with hearing | 21 (30) | 0.3 | 0.7 | 5 (7) | 14 (20) | 0.3 | 0.8 | 5 (7) | 13.9 | <.001b |

| Having difficulty in following directions | 20 (29) | 0.3 | 0.8 | 5 (7) | 15 (22) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 4 (6) | 5.5 | .02b |

| Expressing feelings of hopelessness or sadness about the future | 19 (28) | 0.6 | 1.1 | 12 (17) | 18 (26) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 12 (17) | 18.7 | <.001b |

| Waking up others at night | 14 (20) | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3 (4) | 15 (22) | 0.2 | 0.6 | 3 (4) | 4.6 | .03b |

| Making comments about feeling like a failure or about not having any worthwhile accomplishment in life | 9 (13) | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3 (4) | 12 (17) | 0.3 | 0.8 | 6 (9) | 5.3 | .02b |

| Making comments about death of self or others | 10 (15) | 0.3 | 0.9 | 5 (7) | 11 (16) | 0.4 | 1.0 | 7 (10) | 10.1 | .001b |

| Having nightmares | 7 (10) | 0.1 | 0.6 | 3 (4) | 9 (13) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 3 (4) | 1.7 | .20 |

| Engaging in behaviors that are potentially dangerous to self or others | 5 (7) | 0.1 | 0.4 | 2 (3) | 8 (12) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 4 (6) | 0.7 | .40 |

| Caregiver-perceived distress total score | 8.9 | 9.3 | 7.9 | 9.6 | ||||||

Caregiver-perceived distress at 1 month and at 6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit reflected by the percentage of caregivers who reported problem behavior, item means, and percentage of caregivers who were moderately, very much, or extremely bothered or upset by the patient’s problem behavior (item score ≥2).

χ2 test shows a difference in the proportion of caregivers who identified the presence of each behavior at 1 month and at 6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit.

Among the 18 problem behaviors listed in Table 5, almost half of caregivers (48%) reported 4 or more problem behaviors at 6 months after ICU discharge. The 6 most frequently reported problem behaviors were “difficulty in doing things for self,” “anxious or worried,” “pain or discomfort,” “appeared sad or depressed,” “arguing, irritable, or complaining” (at 1 month only), and “having trouble in falling asleep” (at 6 months only). Chi-squared test revealed no difference in proportion of caregivers who identified these 6 problem behaviors either by patient’s disposition or patient’s functional status.

Caregiver distress scores for each problem behavior showed caregivers were most distressed by patient’s pain or discomfort at both measurement intervals (Table 5). Among caregivers who reported pain or discomfort in patients, 35% reported moderate or greater level of distress at 1 month after ICU discharge and 29% at 6 months after ICU discharge.

Change in Caregivers’ Perceived Lifestyle Restrictions

Although mean CRF scores decreased over time, no significant interaction was found between time and patients’ disposition (F = 2.35; P = .10; partial η2 = 0.07; observed power = 0.46). Irrespective of time, CRF scores differed significantly by disposition (F = 4.31; P = .02; partial η2 = 0.12; observed power = 0.73). Bonferroni post-hoc comparison showed higher mean CRF scores at 6 months after ICU discharge in caregivers of patients who never returned home for 6 months compared with the caregivers of patients who returned home at 1 month after ICU discharge as well as the caregivers of patients who returned home at 6 months after ICU discharge (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of scores on Changes in Role Function subscale by disposition of patient (N =69)

| Changes in Role Function score, mean (SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months since discharge from intensive care unit |

Home at 1 month (n = 20) |

Home at 6 months (n = 36) |

Never returned home (n = 13) |

Pa |

| 1 | 21.9 (7.1) | 22.9 (8.5) | 25.1 (9.8) | >.99b |

| .87c | ||||

| >.99d | ||||

| 6 | 15.5 (6.0) | 19.1 (8.2) | 26.1 (9.5) | .34b |

| .001c | ||||

| .02d | ||||

Bonferroni post-hoc comparison was used.

Home at 1 month after discharge from intensive care unit vs Home at 6 months after discharge from intensive care unit.

Home at 1 month after discharge from intensive care unit vs Never returned home.

Home at 6 months after discharge from intensive care unit vs Never returned home.

Changes in CRF scores over time were not significantly different by patients’ functional status (F = 2.36; P = .10; partial η2 = 0.07; observed power = 0.46). Irrespective of time, CRF scores differed significantly by patients’ functional status (F = 5.30; P = .007; partial η2 = 0.14; observed power = 0.82). Bonferroni post-hoc comparison showed that the mean CRF score was higher in caregivers of patients who never recovered to their functional status before ICU admission compared with caregivers of patients who recovered to their functional status before ICU admission by 6 months after ICU discharge (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison of scores on Changes in Role Function subscale by patient’s functional status (N = 69)

| Months since discharge from intensive care unit (ICU) |

Changes in Role Function score, mean (SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 1 month (n = 7) |

Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 6 months (n = 18) |

Never recovered to same level as before ICU admission (n = 44) |

Pa | |

| 1 | 23.4 (10.5) | 20.6 (6.8) | 24.0 (8.5) | >.99b |

| >.99c | ||||

| .45d | ||||

| 6 | 15.4 (6.3) | 14.0 (4.7) | 22.2 (9.0) | >.99b |

| .12c | ||||

| .001d | ||||

Bonferroni post-hoc comparison was used.

Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 1 month after ICU discharge vs Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 6 months after ICU discharge.

Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 1 month after ICU discharge vs Never recovered to same level as before ICU admission.

Recovered to same level as before ICU admission at 6 months after ICU discharge vs Never recovered to same level as before ICU admission.

Changes in CRF scores did not differ significantly by any of the caregiver characteristics, including age (F = 0.01; P = .92; partial η2 < 0.0001; observed power = 0.05), sex (F = 0.93; P = .39; partial η2 = 0.03; observed power = 0.21), or relationship to patient (F = 0.03; P = .86; partial η2 < 0.0001; observed power = 0.05).

Change in Caregivers’ Perceived Distress

The change in caregiver distress scores over time did not differ significantly by patients’ disposition (F = 0.47; P = .63; partial η2 = 0.01; observed power = 0.12). Irrespective of time, caregiver distress scores were not different by disposition (F = 0.09; P = .92; partial η2 = 0.003; observed power = 0.06). Neither did patients’ functional status show any difference in the change in caregiver distress scores over time (F = 0.59; P = .56; partial η2 = 0.02; observed power = 0.10). Irrespective of time, caregiver distress scores did not different significantly by patients’ functional status (F = 0.70; P = .50; partial η2 = 0.02; observed power = 0.16).

Changes in caregiver distress scores did not differ significantly by any of the caregiver characteristics, including age (F = 0.93; P = .34; partial η2 = 0.01; observed power = 0.16), sex (F = 0.21; P = .81; partial η2 = 0.01; observed power = 0.08), or relationship to patient (F = 0.56; P = 0.46; partial η2 = 0.01; observed power = 0.11).

Discussion

Major findings of this study were as follows: (1) caregivers of CCI patients reported fewer lifestyle restrictions at 6 months after ICU discharge, although patients’ problem behaviors and caregivers’ distress were unchanged; (2) caregivers of CCI patients who were institutionalized or failed to regain level of functional status before ICU admission at 6 months after ICU discharge perceived more restrictions in their lifestyle; (3) no evidence was found that caregivers’ lifestyle restrictions or distress were influenced by caregivers’ age, sex, or relationship to patients; (4) more than 20% of caregivers perceived moderate or greater restrictions in nearly all areas of daily life, particularly the areas related to social life or personal recreation, and (5) negative emotions and pain were frequently reported problem behaviors and caused moderate or greater distress in more than 25% of caregivers. Findings from this study highlight the challenges encountered by informal caregivers after ICU discharge.

As might be expected, caregivers of CCI patients reported more lifestyle restrictions in personal and social interactions. At 1 month after ICU discharge, most reported limited visiting with friends and almost half reported participating less often in hobbies, sports, or recreation, consistent with results of prior studies. In their 6-month follow-up, Douglas et al12 reported that caregivers of the CCI have limited privacy, money, energy, and personal freedom. In their 1-year follow-up study, Rossi-Ferrario et al17 reported restrictions in the social life in 40 caregivers of patients who had a tracheostomy due to chronic respiratory failure. In their study, 88% of caregivers reported that they rarely went to social meetings and restricted outdoor leisure activities and almost 80% reported that they hardly ever saw their friends in the previous year.17

At 6 months after ICU discharge, personal and social activities continued to be limited, although fewer reported restrictions. Mean scores rating caregivers’ lifestyle restrictions decreased from 1 month (mean score, 23.0) to 6 months (mean score, 19.4) after ICU discharge. The mean CRF score at 6 months after ICU discharge in this study was almost identical to the score reported in a previous study that followed similar caregivers for 12 months (mean score, 22.1 at 2 months; mean score, 20.5 at 6 months; mean score, 20.0 at 12 months; P = .38).18 Although caregivers in the present study reported fewer lifestyle restrictions at 6 months after ICU discharge, more than one-third continued to report limitations in visiting with friends and participating in hobbies and recreation. Of concern, approximately 20% reported problems in sleeping and eating.

At 1 month after ICU discharge, more than half of caregivers in the present study identified problem behaviors of patients that are related to physical (“difficulty doing things for self,” “pain and discomfort”) or psychological (“anxious or worried,” “sad or distressed”) issues as causes of distress. These findings were essentially identical to those from a prior study that used the same measurement.12,16,18 In a 2-month follow-up study16 of 115 patients who received mechanical ventilation for at least 48 hours (mean, 14 days), the same 4 problem behaviors were reported most frequently. Providing emotional support has been reported as the most difficult task for caregivers of other acute or chronic diseases.31–33 Among the CCI, negative physical,23,34,35 neurocognitive,36–39 and psychological40 outcomes can last for months or years after discharge from the ICU.41–43 Although some of these behaviors (eg, sad, distressed, anxious) are most likely the result of extended illness, others (eg, pain) should be amenable to evidence-based interventions.

In this study, caregivers’ perceived lifestyle restrictions differed according to the patient’s disposition and functional status. Although CRF scores decreased markedly in caregivers of patients who returned home at 1 month after ICU discharge, CRF scores were persistently high in caregivers of patients who never returned home. Given the care involved, one might assume that caregivers would perceive more restrictions if the patient returned home because they would need to spend more time assisting with daily activities and other needs. However, findings of this study suggest that caregivers of patients who were institutionalized for 6 months after ICU discharge perceive substantial lifestyle restrictions. Compared with institutionalized patients, some studies have reported more caregiving if patients returned home,16,18 whereas others have reported almost the same amount of time if patients were institutionalized.12 In this study, other information related to caregiving, such as number of caregiving hours per day, extra help from other family members or friends, or detailed areas of involvement for institutionalized patients, was not collected. Therefore, it was not possible to determine specific factors that influenced perceived restrictions. Patients’ functional status is another important consideration. In this study, when patients never regained the functional status they had before ICU admission, caregivers’ lifestyle restrictions and distress were unchanged over 6 months.

Implications

Consistent with prior studies, results of the present study indicated a substantial burden in caring for the CCI, leading to restrictions in caregivers’ lifestyle. The problem behaviors that prompt these challenges are both physiological and psychological. The complexity and scope of problems are challenging. A randomized trial14,44 that tested outcomes of a disease management program consisting of emotional support (eg, discussion, referrals, and reassurance) and instrumental support (eg, care coordination, education, and communication) in caregivers of the CCI reported that the intervention group had significantly fewer mean days of rehospitalization and lower health care costs.44 However, the intervention did not significantly contribute to improving caregiver’s depression, physical health problems, or burden.14

Findings of this study suggest that interventions designed to enhance coping, decrease social isolation, and improve patients’ functional status may be helpful. Technology can be helpful, for example, Internet-based programs can provide education and emotional support, inform caregivers about resources, and provide support from others. Because many CCI patients have compromised functional status, interventions that promote improved mobility may contribute to better caregiver outcomes. In addition to conventional physical and occupational therapies, an intervention designed to increase muscle strength may hasten recovery and ultimately lessen caregiver burden.45,46 Longitudinal exploration of the caregiving experience by using a mixed methods approach may enhance understanding of predictors of lifestyle restrictions and distress. Prior studies have primarily relied on results of self-reported survey data. Adding physiological measurements of the stress response may be warranted to better understand and support caregivers of the CCI.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the attrition rate was high, which limited the sample size and therefore the generalizability of the results. Only one-third of the caregivers who were initially enrolled completed the 6-month follow-up despite use of monthly phone calls to promote retention. Potentially, caregivers who withdrew from the study experienced more lifestyle restrictions and distress. We did not record the characteristics of those who refused to participate or withdrew during follow-up. Such information should be obtained in future studies to assist in interpreting findings.

Second, in our study, we collected limited data on patients’ and/or caregivers’ lifestyles before ICU admission and limited follow-up data (eg, days of mechanical ventilation after ICU discharge). Because ICU admission is an unplanned event, it was necessary to rely on caregivers’ recall to assess patients’ baseline before ICU admission. Patients’ pre-ICU functional status may have been overestimated or underestimated by caregivers. Also, past caregiving experiences might have led to different results. A more detailed profile that included characteristics, such as years of education, income, religious background, caregiver’s own chronic health problems would provide better understanding of the caregiving experience. Finally, participants were predominantly white. As differences in race and ethnicity affect family dynamics and values, a more diverse sample might yield different findings.

Conclusion

Findings of this study suggest that future interventions should attempt to decrease the isolation of caregivers of CCI patients and improve patients’ functional status as a means to promote greater independence of patients and caregivers. Longitudinal exploration of the caregiving experience using a mixed methods approach may further enhance understanding of predictors of lifestyle restrictions and distress in caregivers of the CCI.

Acknowledgments

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Nursing Research, US Public Health Service (R01 NR 05204, T32 NR 008857, and F32 NR 011271).

Footnotes

To purchase electronic or print reprints, contact The InnoVision Group, 101 Columbia, Aliso Viejo, CA 92656. Phone, (800) 899-1712 or (949) 362-2050 (ext 532); fax, (949) 362-2049; reprints@aacn.org

Contributor Information

JiYeon Choi, assistant professor in the Department of Acute/Tertiary Care at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing..

Michael P. Donahoe, associate professor of medicine and director of the medical intensive care unit at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine..

Thomas G. Zullo, professor emeritus in the Department of Acute /Tertiary Care at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing..

Leslie A. Hoffman, professor and chair of the Department of Acute/Tertiary Care at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing..

REFERENCES

- 1.National Family Caregivers Association. [Accessed February 11, 2008];Caregiver statistics: statistics on family caregivers and family caregiving. 2008 http://www.thefamilycaregiver.org/who/stats.cfm.

- 2.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, Burton L, Hirsch C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: the caregiver health effects study—an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19(2):110–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02883327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chronically Critically Ill. [Accessed December 8, 2009];CCI definition. 2005 http://fpb.case.edu/ChronicallyCriticallyIll/definitions.shtm.

- 5.Combes A. The long and difficult road to better evaluation of outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation: not yet a highway to heaven. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):120. doi: 10.1186/cc5701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White AC, O’Connor HH, Kirby K. Prolonged mechanical ventilation: review of care settings and an update on professional reimbursement. Chest. 2008;133(2):539–545. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carson SS, Bach PB. The epidemiology and costs of chronic critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2002;18(3):461–476. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheinhorn DJ, Hassenpflug MS, Votto JJ, et al. Ventilator-dependent survivors of catastrophic illness transferred to 23 long-term care hospitals for weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2007;131(1):76–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zilberberg MD, de Wit M, Pirone JR, Shorr AF. Growth in adult prolonged acute mechanical ventilation: implications for healthcare delivery. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(5):1451–1455. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181691a49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn JM, Angus DC. Health policy and future planning for survivors of critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(5):514–518. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efb7c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubenfeld GD, Curtis JR. Health status after critical illness: beyond descriptive studies. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(10):1626–1627. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1855-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas SL, Daly BJ. Caregivers of long-term ventilator patients: physical and psychological outcomes. Chest. 2003;123(4):1073–1081. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron JI, Herridge MS, Tansey CM, McAndrews MP, Cheung AM. Well-being in informal caregivers of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):81–86. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000190428.71765.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Impact of a disease management program upon caregivers of chronically critically ill patients. Chest. 2005;128(6):3925–3936. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster M, Chaboyer W. Family carers of ICU survivors: a survey of the burden they experience. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003;17(3):205–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Im K, Belle SH, Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Chelluri L. Prevalence and outcomes of caregiving after prolonged (≥48 hours) mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest. 2004;125(2):597–606. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi Ferrario S, Zotti AM, Zaccaria S, Donner CF. Caregiver strain associated with tracheostomy in chronic respiratory failure. Chest. 2001;119(5):1498–1502. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Qin L, et al. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(2):167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwashyna T, Christakis N. Spouses of mechanically ventilated patients have increased mortality [abstract]; Proceedings of American Thoracic Society; May 19–24, 2006; San Diego, CA. Abstract 833. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duke University Medical Center; Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development. [Accessed October 7, 2010];Older American Resources and Services (OARS); Multi-dimensional Assessment Survey. 1978 http://www.geri.duke.edu/service/oars.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz R, Williamson G. Health effects of caregiving: Prevalence of mental and physical illness in Alzheimer’s caregivers. In: Light E, Niederehe G, Lebowitz BD, editors. Stress Effects on Family Caregivers of Alzheimer’s Patients. New York, NY: Springer; 1994. pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit S, Vitaliano PP. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: the revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychol Aging. 1992;7(4):622–631. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quality of Life After Mechanical Ventilation in the Aged Society Investigators. 2-month mortality and functional status of critically ill adult patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2002;121(2):549–558. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: Dimensions and Practical Applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire: a review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(1):167–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim Y, Hoffman LA, Choi J, Miller TH, Kobayashi K, Donahoe MP. Characteristics associated with discharge to home following prolonged mechanical ventilation: a signal detection analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(6):510–520. doi: 10.1002/nur.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierce C, Block R, Aguinis H. Cautionary note on reporting eta-squared values from multifactor ANOVA designs. Educ Psychol Meas. 2004;64(6):916–924. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens J. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakas T, Burgener SC. Predictors of emotional distress, general health, and caregiving outcomes in family caregivers of stroke survivors. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2002;9(1):34–45. doi: 10.1310/GN0J-EXVX-KX0B-8X43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):P112–P128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pressler SJ, Gradus-Pizlo I, Chubinski SD, et al. Family Caregiver Outcomes in Heart Failure. Am J Crit Care. 2009;18(2):149–159. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carson SS, Bach PB, Brzozowski L, Leff A. Outcomes after long-term acute care. An analysis of 133 mechanically ventilated patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(5 Pt 1):1568–1573. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9809002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, Parkinson RB, Chan KJ, Orme JF., Jr Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):340–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM, et al. Six-month neuropsychological outcome of medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1226–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000059996.30263.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones C, Griffiths RD, Slater T, Benjamin KS, Wilson S. Significant cognitive dysfunction in non-delirious patients identified during and persisting following critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(6):923–926. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nelson JE, Tandon N, Mercado AF, Camhi SL, Ely EW, Morrison RS. Brain dysfunction: another burden for the chronically critically ill. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(18):1993–1999. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, Young JD. The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1506–1518. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carson SS. Outcomes of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12(5):405–411. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000244118.08753.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chelluri L, Im KA, Belle SH, et al. Long-term mortality and quality of life after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(1):61–69. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098029.65347.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cox CE, Carson SS, Lindquist JH, Olsen MK, Govert JA, Chelluri L. Differences in one-year health outcomes and resource utilization by definition of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R9. doi: 10.1186/cc5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Trial of a disease management program to reduce hospital readmissions of the chronically critically ill. Chest. 2005;128(2):507–517. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quittan M, Wiesinger GF, Sturm B, et al. Improvement of thigh muscles by neuromuscular electrical stimulation in patients with refractory heart failure: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(3):206–214. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200103000-00011. quiz 215–206, 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zanotti E, Felicetti G, Maini M, Fracchia C. Peripheral muscle strength training in bed-bound patients with COPD receiving mechanical ventilation: effect of electrical stimulation. Chest. 2003;124(1):292–296. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]