Abstract

Background

Sigma (σ) factors are transcription initiation factors that modulate Mtb's response to changes in extracellular milieu, allowing it to survive stress.

Methods

We analyzed the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c under various stress conditions that mimic the intracellular environment faced by Mtb.

Results

MT2816/Rv2745c expression was induced in Mtb following redox stress, heat- and acid-shock and intracellular replication. Its expression was also induced by SDS and THZ (thioridazine), treatments that impact Mtb cell-envelope. However, treatment with INH or ethambutol, front-line anti-TB drugs which also target cell-envelope, didn't induce the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c. Studies using Δ−σH and Δ−σE mutants showed that σH was required for the induction of MT2816/Rv2745c. Conditional expression of the MT2816/Rv2745c in Mtb showed that apart from regulating proteolysis, this gene may control the expression of trehalose biosynthesis and impact the maintenance of cellular redox potential and energy generation.

Conclusions

The protein encoded by MT2816/Rv2745c is important for the pathogen's response to stress conditions that mimic in-vivo growth and it is subject to complex regulation. The MT2816/Rv2745c encoded protein likely functions by protecting intracellular redox potential and by inducing the expression of trehalose, a constituent of Mtb cell-walls that is important for defense against cell-surface and oxidative stress.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, stress, σ factor, MT2816, Rv2745c, thioridazine

Introduction

TB is annually responsible for about 1.75 million deaths [1]. The failure of vaccination [2] and the emergence of drug resistant Mtb have further complicated this situation [3]. To help develop effective anti-TB solutions, we seek to better understand the mechanisms that help Mtb establish long-term infection.

Sigma (σ) factors modulate gene expression in eubacteria, in response to changes in extracellular milieu [4]. While principal σ factors regulate housekeeping gene functions, alternative σ factors control adaptation to specific environmental stimuli and stress [5]. The temporal expression of specific regulons controlled by one or more alternative sigma factors likely allows Mtb to survive in multiple phases of TB [6].

Well characterized Mtb σ factors σH, σE and σB act in a network, likely performing overlapping functions [7-10]. σH is induced by multiple stress conditions [8, 10, 11], and phagocytosis [12, 13]. Its activity is regulated by an anti-sigma factor [14] and a protein kinase [15]. The Δ−σH mutant is attenuated in-vivo [8]. σH directly regulates the transcription of 31 genes, including the σE, σB and the thioredoxin regulon [8, 10]. Induction of σH causes dramatic downstream changes in Mtb gene-expression [16]. σE is also induced upon uptake by macrophages [12, 17] and multiple stress conditions [17, 18]. The Δ−σE mutant is not lethal in mice and induces granulomas with lower inflammation [19, 20]. σE regulates the expression of σB, hsp and htpX. σE is transcribed in either a σH [8, 10] or an MprAB-dependent [21, 22] manner, and is subject to regulation by an anti-sigma factor [23], and by the protein kinase which also influences the expression of σH [24]. The levels of the MT2816/Rv2745c gene are up-regulated in σH [16] and σE dependent manner [7] and by treatment with the anti-bacterial vancomycin [25]. In order to characterize the role of the MT2816/Rv2745c encoded protein, we studied its expression under conditions of environmental stress (redox and oxidative stress, heat- and acid-shock, cell-wall damage, nutrition starvation and treatment with anti-bacterials) and during intra-phagosomal growth. These assays were performed in wild-type Mtb, the Δ−σH and the Δ−σE mutants, in order to identify the effect of these two σ factors of MT2816/Rv2745c induction. The expression of σH, σE and σB was simultaneously analyzed. Given this experimental design, we hoped to not only find out the environmental conditions that induce the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c, but also compare its expression in strains unable to induce either σH or σE. Finally, we also identified the influence of the MT2816/Rv2745c encoded transcription factor on the global transcriptome profile of Mtb.

Materials and Methods

Culture conditions

Wild-type Mtb CDC1551 and its isogenic Δ−σH and Δ−σE mutants were cultured as described [16] and harvested at early (A600=0.3), mid (A600=0.6) and late (A600=1.2) stages of growth. We measured the effect of the following stress conditions on the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c for 2 hrs (samples collected at pre-stress, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min post-stress): 10 mM diamide [16], 0.01% H2O2, 0.1% SDS, 5% ethanol, heat-shock (45°C), acid-shock (pH 4.5), nutrition-limitation [26], and treatment with various anti-mycobacterials [0.75μg/mL INH, 7.5μg/mL Streptomycin, 12μg/mL ETMB, 10 μg/mL THZ (thioridazine)] [27]. 25 mL samples were used to isolate RNA and protein from each time point of each condition.

Macrophage cultures and infection

Primary macrophages were isolated from specific-pathogen free rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) femur bone marrow at necropsy. Macrophages were grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM, Mediatech), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (BioWhittaker), seeded with 106cells/ml and infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 [28]. After 4h, the cells were extensively washed to remove extracellular bacilli and placed in culture for another 24 hours. Intracellular bacilli were liberated from lyzed phagocytes by differential centrifugation [28] and Mtb RNA isolated. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c and σ factors was compared between Mtb grown in phagocytes and in-vitro.

Isolation of RNA and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RNA isolation and qPCR methods have been previously described [16]. The specific oligonucleotides used for qPCR and their DNA sequences are listed in Supplement 1A. Expression was normalized using σA, and the average relative changes in amplification cycles determined for three replicate experiments in Mtb relative to either the Δ−σH or the Δ−σE mutants.

Isolation of proteins, SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

The anti-MT2816/Rv2745c antibody, protein isolation and Western blotting procedures have been previously described [16].

DNA microarray experiments

We compared the transcriptome of an Mtb strain carrying a copy of the MT2816 gene under the control of a tetracycline promoter [29], in presence and absence of the inducer. RNA was isolated 1 hr post-tetracycline addition, and Cy-labeled products were hybridized to a custom designed 4 × 44K multipack Mtb tiling microarray, procured from Agilent Technologies. LOWESS normalization was used to eliminate intensity-specific bias [16]. Since the tiling array encodes several probes for each gene, feature outliers were eliminated whereas all other reporters were combined, and their data summarized. Genes were considered to be differentially expressed if their expression was significantly perturbed (50% or more in each of the three biological replicates).

Results

Expression of MT2816/Rv2745c during normal growth conditions

The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in wild-type Mtb and the two mutants, at mid (A600=0.6) and late (A600=1.2) stage of growth in rich broth remained unchanged, relative to its expression at an early stage of growth (A600=0.3) (Supplement 1B).

Expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in response to environmental stress conditions known to induce either σH or σE

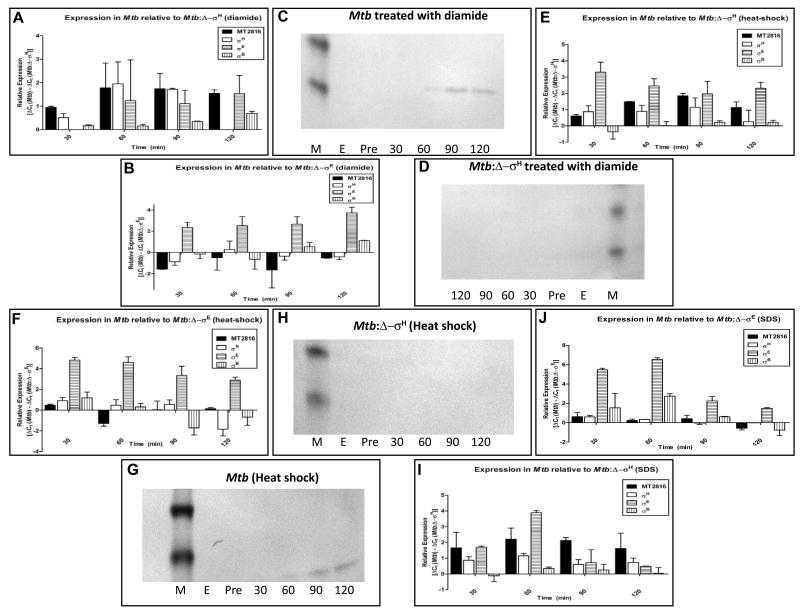

Redox stress by diamide induces the expression of σH and its downstream regulon in Mtb [8, 10, 16]. Upon stress with diamide, the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was dramatically induced in wild-type Mtb but not the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1A). The levels of the MT2816/Rv2745c transcript were significantly induced at 30′, peaked at 60′, and remained significantly elevated till the 120′ time point (Fig. 1A). The levels of σH, σE and σB were also induced in Mtb, relative to the Δ−σH mutant, following diamide treatment (Fig. 1A). On the contrary, the expression of MT2816 and σH was not higher in Mtb, relative to the Δ−σE mutant, upon diamide stress (Fig. 1B). The expression of σE was expectedly higher in Mtb relative to the Δ−σE mutant. These results indicate that σH may be necessary for the expression of MT2816 during stress. At the protein level, MT2816/Rv2745c was detected at 60′ and the subsequent time points in Mtb (Fig. 1C). However, the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c protein was not detected in the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1D), confirming qPCR results (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

MT2816/Rv2745c expression in wild-type Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant and the Δ−σE mutant in response to stress conditions known to induce σH or σE.

We studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c transcript and protein by qPCR and immunoblot respectively at 0′ (pre-stress), 30′, 60′, 90′ and 120′ post-stress in Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant and the Δ−σE mutant cultures following treatment with diamide, SDS and heat-shock: qPCR in Mtb (Fig. 1A), the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1C) and the Δ−σE mutant (Fig. 1E), following diamide stress. MT2816/Rv2745c-specific immunoblot in Mtb (Fig. 1B) and the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1D) following diamide stress. qPCR in Mtb (Fig. 1F), the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1H) and the Δ−σE mutant (Fig. 1J) following heat-shock. MT2816/Rv2745c-specific immunoblot in Mtb (Fig. 1G) and the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1I) following heat-shock. qPCR in Mtb (Fig. 1K), the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1L) and the Δ−σE mutant (Fig. 1M) following SDS stress. A legend for qPCR graphs is included. Legend for immunoblot samples; M:–Benchmark Prestained molecular weight marker (Invitrogen) (15 and 10 kDa bands are shown); E: empty lane; Pre: 0′ post-stress, 30: 30′ post-stress; 60: 60′ post-stress; 90: 90′ post-stress; 120: 120′ post-stress.

The expression of σH is also induced in Mtb following heat-shock [30]. Hence, we studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in wild-type Mtb, the Δ−σH and the Δ−σE mutants, following heat shock. The levels of MT2816/Rv2745c, σH, σE and σB transcripts were significantly induced following heat-shock in Mtb. The levels of MT2816/Rv2745c, σH and σE were significantly higher in Mtb, relative to the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1E). On the other hand, the levels of MT2816/Rv2745c and σH were not higher in Mtb compared to the Δ−σE mutant (Fig. 1F). Clearly, the sole loss of σE activity in this mutant was not sufficient to abrogate the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c. Western blots confirm that MT2816/Rv2745c protein expression was induced in Mtb (Fig. 1G) but not the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1H).

Damage to Mtb membrane by SDS induces the expression of σE [7]. Hence, we studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c and the three σ factors following SDS treatment. The levels of σE were particularly induced in wild-type Mtb relative to the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 1I). This indicates that the expression of σE is impaired in the Δ−σH mutant. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was higher in Mtb than the Δ−σH mutant following SDS stress. The expression of σH was also slightly higher in Mtb, relative to the Δ−σH mutant. Relative to the Δ−σE mutant, the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c or σH was slightly higher in Mtb (Fig. 1J). However, the expression of σE was expectedly higher in Mtb relative to the Δ−σE mutant (Fig. 1J).

Expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in response to other environmental stress conditions

We then analyzed the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in wild-type Mtb and the two mutant strains, in response to other treatments that mimic environmental stress that intracellular Mtb face. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was not induced in Mtb by treatment with hydrogen peroxide. There was no difference in the levels of MT2816/Rv2745c in Mtb relative to either the Δ−σH (Fig. 2A) or the Δ−σE mutants (Fig. 2B) following this treatment. The expression of this gene was also not induced in Mtb treated with ethanol, relative to either the Δ−σH (Fig. 2C) or the Δ−σE mutants (Fig. 2D) following this treatment. Expectedly, treatment of the Δ−σH mutant with hydrogen peroxide and ethanol did not lead to an induction in the levels of σH, σE or σB (Fig. 2A-D).

Figure 2.

MT2816/Rv2745c expression in Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant and the Δ−σE mutant, in response to various other environmental stress conditions.

We studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c transcript by qPCR at 0′ (pre-stress), 30′, 60′, 90′ and 120′ post-stress in Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant and the Δ−σE mutant cultures following treatment with hydrogen-peroxide, ethanol, nutrition-limitation and acid (low-pH): qPCR in Mtb following stress with hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 2A), ethanol (Fig. 2D), low-pH (Fig. 2G) and nutritional-limitation (Fig. 2J). qPCR in the Δ−σH mutant following stress with hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 2B), ethanol (Fig. 2E), low-pH (Fig. 2H) and nutritional-limitation (Fig. 2K). qPCR in the Δ−σE mutant following stress with hydrogen peroxide (Fig. 2C), ethanol (Fig. 2F), low-pH (Fig. 2I) and nutritional-limitation (Fig. 2L).

The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c, σH and σE was induced in wild-type Mtb relative to the Δ−σH mutant, during acid-shock (Fig. 2E). The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c and σH was comparable between Mtb and the Δ−σE mutant following this stress (Fig. 2F). Although smaller in magnitude than wild-type Mtb, MT2816/Rv2745c induction could also be seen in the two mutant strains, relative to baseline (0′ or pre-stress). Further, the expression of σB significantly increased in the mutant strains relative to Mtb, indicating that σB may directly be induced by certain stress conditions like acid-shock. The expression of neither MT2816/Rv2745c, nor the three σ factors was induced in nutrition-limiting environment, in any of the three strains (Fig. 2G & 2H).

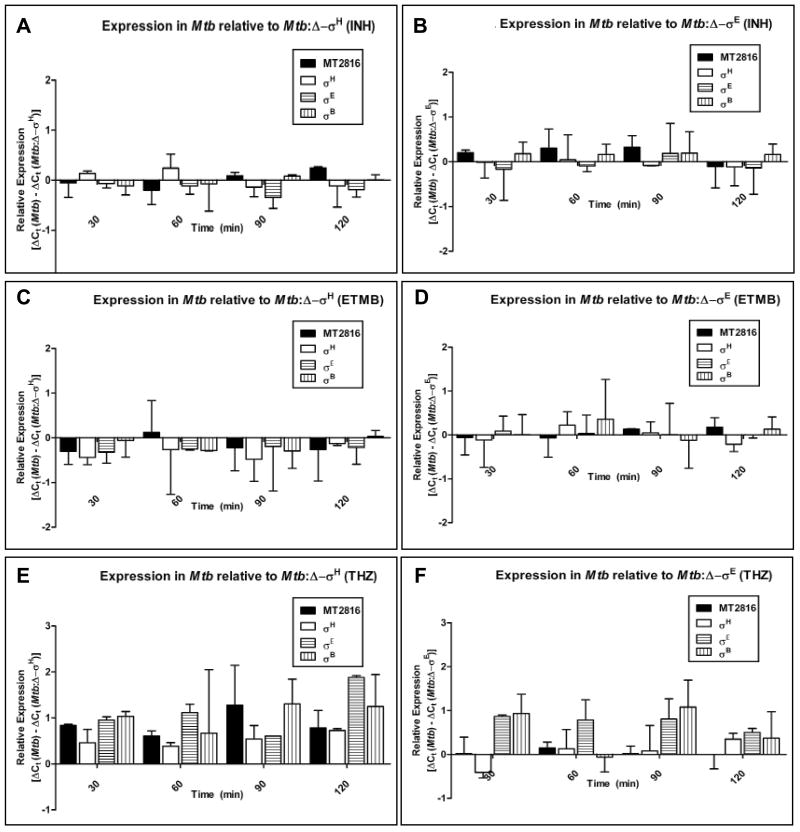

Expression of MT2816/Rv2745c upon treatment with anti-mycobacterial compounds

The levels of MT2816/Rv2745c were recently reported to be induced when Mtb is treated with vancomycin, a glycopeptide antibiotic that interacts with the bacterial cell-wall [25]. We asked whether MT2816/Rv2745c is induced by other agents that target Mtb cell-wall, by studying its expression in Mtb and the two σ factor mutants following treatment with INH and ETMB. These two front-line anti-TB drugs also directly target the cell-wall. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was also studied following treatment with streptomycin, which doesn't target the Mtb cell-wall. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c and the three σ factors, σH, σE or σB, was not perturbed in wild-type Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant or the Δ−σE mutant upon treatment with these antibiotics. The expression of these genes remained unchanged in Mtb, compared to either mutant strain, following treatment with INH (Fig. 3A & 3B), ETMB (Fig. 3C & 3D), or streptomycin (not shown).

Figure 3.

MT2816/Rv2745c expression in Mtb and the Δ−σH mutant, in response to various anti-mycobacterial compounds.

We studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c transcript by qPCR at 0′ (pre-stress), 30′, 60′, 90′ and 120′ post-stress in Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant and the Δ−σE mutant cultures following treatment with IHN, ETMB, Streptomycin and THZ: qPCR in Mtb following INH (Fig. 3A), ETMB (Fig. 3D), Streptomycin and THZ (Fig. 3G) treatment. qPCR in the Δ−σH mutant following INH (Fig. 3B), ETMB (Fig. 3E) Streptomycin and THZ (Fig. 3H) treatment. qPCR in the Δ−σE mutant following INH (Fig. 3C), ETMB (Fig. 3F) and THZ (Fig. 3I) treatment.

THZ is a phenothiazine with potent anti-mycobacterial activity, which perturbs the intra-bacterial redox potential [31, 32]. We have recently shown that THZ also modulates the structure of the Mtb cell-wall [Dutta NK, Mehra S, Kaushal D, 09-PONE-RA-14357R1, in revision]. We therefore studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in a time-dependent manner, following THZ treatment, in wild-type Mtb and the two σ factor mutants. The MT2816/Rv2745c levels exhibited a substantial increase in wild-type Mtb treated with THZ. Relative to the Δ−σH mutant, the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c, as well as σH, σE and σB was significantly higher in Mtb (Fig. 3E). However, when expression was compared between Mtb and the Δ−σE mutant, MT2816/Rv2745c and σH levels were not differentially expressed (Fig. 3F). These results again show the requirement of σH for optimal expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in response to stress.

Expression of MT2816/Rv2745c during intra-phagosomal growth

The expression of both σH and σE is induced in host phagocytes during infection with Mtb [12]. Since the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c appeared to be dependent on σH, we tested if its expression is also induced in host phagocytes. Nonhuman primates most accurately capture various aspects of human TB [33, 34]. We studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in rhesus macaque bone-marrow derived primary (BMD) macrophages, whose phenotype was verified for the expression of immunological markers by flow-cytometry. These cells expressed high levels of macrophage cell-surface markers CD86 and CD163, as well as macrophage activation markers CD11b and HLA-DR (Fig. 4A). BMD macrophages were infected with wild-type Mtb, the Δ−σH or the Δ−σE mutant for 4 hrs, at an MOI of 10 bacilli per BMD macrophage. At this time, extracellular bacilli were washed away, and cells were lysed to recover intracellular bacilli (0 hr time point) or further incubated (24 hr time point). The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was significantly induced in Mtb at 24 hrs, relative to the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 4B) as well as the Δ−σE mutant (Fig. 4C). The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c and all three σ factors was induced at 24 h in Mtb (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

MT2816/Rv2745c expression in wild-type Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant and the Δ−σE mutant, during intra-phagosomal growth

BMDM cultures were subjected to flow cytometry to validate the expression of known macrophage markers (Fig. 4A). We then studied the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c transcript by qPCR following 0′ (pre-stress) and 24 h infection of BMDMs by either Mtb (Fig. 4B), the Δ−σH mutant (Fig. 4C), or the Δ−σE mutant (Fig. 4D).

Changes in Mtb transcriptome induced by the conditional expression of MT2816/Rv2745c

In order to identify the role of the MT2816/Rv2745c encoded transcription factor, we generated a recombinant strain of Mtb CDC1551 with an additional copy of the MT2816 gene, under the transcriptional control of a tetracycline inducible promoter. Transcription was compared using DNA microarrays and the recombinant strain expressing MT2816/Rv2745c under the control of the tetracycline promoter, relative to the parental strain, that doesn't express the recombinant MT2816 gene. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was highest 6 hrs post-induction, as measured by qPCR, but was sufficiently induced 1 and 2 hrs post-induction (not shown). In order to identify direct effects of MT2816/Rv2745c, the microarray experiment was performed using the 1 hr post-induction samples. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was induced (∼3-fold) in each of the three independent biological replicates (Table 1A, Supplement 2A). 141 genes showed a higher level of expression and 47 genes showed a lower level of expression following the induction of MT2816/Rv2745c.

Table 1.

A short-list of key Mtb genes with either a higher (A) or a lower (B) expression following the chemical induction of MT2816/Rv2745c expression.

| Table 1A: Functional characterization of Mtb genes that exhibit a higher expression following the chemical induction of MT2816/Rv2745c gene | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Function | Gene ID | Gene Description | Log2 Fold Change ± Standard deviation |

| Heat-shock | groES | 10 KDa Chaperonin | 0.86 ± 0.02 |

| hsp | Heat Shock Protein | 1.18 ± 0.22 | |

| TA family | Rv0608 | Antitoxin | 1.02 ± 0.24 |

| Rv0623 | Antitoxin | 1.12 ± 0.20 | |

| Rv0624 | Toxin | 1.02 ± 0.20 | |

| Rv0960 | Toxin | 1.00 ± 0.05 | |

| Rv2010 | Antitoxin | 0.90 ± 0.05 | |

| Rv2104c | Antitoxin | 1.00 ± 0.17 | |

| Virulence and detoxification | bcpB | Bacterioferritin Comigratory Protein B | 1.51 ± 0.40 |

| bfrB | Bacterioferritin B | 0.95 ± 0.11 | |

| clpX | Clp protease ATP-binding subunit | 0.89 ± 0.07 | |

| clpP2 | Clp protease proteolytic subunit | 0.99 ± 0.08 | |

| clpC1 | Clp protease catalytic subunit | 1.13 ± 0.43 | |

| rpfA | Resuscitation Promotion Factor | 1.10 ± 0.37 | |

| Lipid metabolism and virulence factor lipid synthesis | otsA | Trehalose Phosphate Synthetase | 1.90 ± 0.19 |

| accA3 | Acetyl/Propionyl CoA Carboxylase | 1.22 ± 0.04 | |

| desA3 | Acyl-[Acyl Carrier Protein] desaturase | 1.08 ± 0.15 | |

| fadD2 | Fatty Acid CoA Ligase | 1.24 ± 0.25 | |

| fadD31 | Acyl CoA ligase | 1.04 ± 0.11 | |

| fadE5 | Acyl CoA Dehydrogenase | 1.04 ± 0.31 | |

| fas | Fatty acid Synthase | 1.27 ± 0.10 | |

| plsC | Phospholipid Biosynthesis Bifunctional Enzyme | 1.55 ± 0.51 | |

| Transporters or cell wall/membrane components | arsB1 | Arsenic Transport Integral Membrane Protein | 0.92 ± 0.01 |

| Rv1348 | Drugs Transporter | 0.95 ± 0.30 | |

| iniB | INH Inducible Protein B | 1.12 ± 0.27 | |

| mmr | Multidrugs Transporter | 1.26 ± 0.34 | |

| mscL | Large Conductance Ion Mechano-sensitive Channel | 0.82 ± 0.08 | |

| Intermediary metabolism | ctaE | Cytochrome Oxidase | 1.80 ± 0.62 |

| ctpH | Metal Cation Transporting P-type ATPase | 0.96 ± 0.08 | |

| cysE | Serine Acetyl Transferase | 1.36 ± 0.79 | |

| fdxC | Ferridoxin C | 1.30 ± 0.32 | |

| iscS | Cysteine Desulfurase | 1.38 ± 0.61 | |

| prcA | Proteasome alpha subunit | 1.65 ± 0.82 | |

| prcB | Proteasome beta subunit | 1.02 ± 0.33 | |

| rpiB | Ribose-5 Phosphate Isomerase | 2.17 ± 1.19 | |

| Rv0216 | Double Hotdog Hydratase | 2.00 ± 0.42 | |

| Rv0730 | GCN5 N-Acetyl Transferase | 2.49 ± 0.55 | |

| Rv0802c | GCN5 N-Acetyl Transferase | 1.15 ± 0.27 | |

| Rv1106c | 3-beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase | 1.09 ± 0.11 | |

| Rv2775 | GCN5 N-Acetyl Transferase | 0.82 ± 0.15 | |

| Transcriptional regulators | cmtR | Transcriptional regulator | 1.36 ± 0.25 |

| mtrA | Two-component Signal Transduction Transcriptional regulator | 0.77 ± 0.11 | |

| pknD | Serine Threonine Protein Kinase D | 1.14 ± 0.06 | |

| Rv2745c | Transcriptional regulator | 1.69 ± 0.06 | |

| whiB2 | Transcriptional regulator | 0.85 ± 0.05 | |

| Table 1B: Functional characterization of Mtb genes that exhibit a higher expression following the chemical induction of MT2816/Rv2745c gene | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Function | Gene ID | Gene Description | Log2 Fold Change ± Standard deviation |

| Lipid metabolism and virulence factor lipid synthesis | fadE21 | Acyl CoA Dehydrogenase | -0.93 ± 0.22 |

| pks8 | Polyketide Synthase | -1.69 ± 0.04 | |

| Intermediary metabolism | aao | D amino acid Oxidase | -1.00 ± 0.24 |

| argJ | Glutamate N-Acetyltransferase | -1.81 ± 0.14 | |

| gltA1 | Citrate Synthase | -1.31 ± 0.22 | |

| hemD | Uroporphyrin-III C-Methyltransferase | -1.02 ± 0.04 | |

| menA | 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-Naphthoate Octaprenyltransferase | -1.26 ± 0.05 | |

| menB | Naphthoate Synthase | -0.94 ± 0.19 | |

| nuoJ | NADH Dehydrogenase I | -0.78 ± 0.09 | |

| pgi | Glucose-6 Phosphate Isomerase | -1.20 ± 0.05 | |

| sdhA | Succinate Dehydrogenase (Flavoprotein subunit) | -0.80 ± 0.07 | |

| sdhB | Succinate Dehydrogenase (Iron-Sulphur Protein subunit) | -0.79 ± 0.04 | |

| sucC | Succinyl CoA Synthetase (beta chain) | -0.83 ± 0.01 | |

| Transcriptional regulators | katG | Catalase Peroxidase Peroxynitritase | -1.38 ± 0.08 |

| pknA | Serine Threonine Protein Kinase A | -1.69 ± 0.04 | |

| Conserved Proteins | Rv2743c | Conserved transmembrane Alanine Rich Protein | -1.12 ± 0.07 |

| Rv2744c | Conserved 35 kDa Alanine Rich Protein | -1.00 ± 0.09 | |

The expression of heat shock genes hsp and groES; toxin-antitoxin, Clp protease and bacterioferretin genes, was also induced. The expression of otsA, which codes for a key enzyme that synthesizes trehalose phosphate, a multifunctional molecule thought to be important for surface and oxidative stress defense, as well as mycolic acid transport, was highly induced in the MT2816/Rv2745c expressing strain, along with numerous other lipid/fatty acid biosynthetic genes (Table 1A, Supplement 2A). The expression of ribulose phosphate epimerase (rpe), protein kinase pknD, INH-inducible protein iniB, multi-drug transporter mmr, proteasome subunits prcA and prcB, and GCN5 N-acetyl transferases (Rv730, Rv0802 and Rv2705) was also induced (Table 1A, Supplement 2A).

Interestingly, the expression of two neighboring genes, Rv2744c and Rv2743c, was repressed in Mtb after conditional induction of MT2816/Rv2745c (Table 1B, Supplement 2A). Other genes with lower expression following the conditional induction of MT2816/Rv2745c included katG and pknA, succinate dehydrogenases - sdhA and sdhB, succinyl coA synthetase – sucC and enzymes of menaquinone biosynthesis – menA and menB. The global expression profiles showed that the stress response phenotype of the MT2816/Rv2745c encoded protein may help Mtb to adapt to and manage changes in energy metabolism and cellular redox potential.

Discussion

Extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors regulate bacterial adaptation to extracellular environment. Therefore, genes encoding these factors are of immense interest as potential regulators of virulence in-vivo. Mtb encodes ten ECF σ factors, most of which regulate key stress-defense regulons and are required for virulence [35]. Transcriptional regulation of σ factor networks in Mtb is complex and interlinked: σH can induce the expression of σE and σB [8, 10, 16]; however, while σE can be induced independent of σH by other environmental signals. This suggests that parts of the σH/σE/σB network can be independently regulated under certain conditions [21].

Orthologs of MT2816/Rv2745c are present in all mycobacteria. Orthologs of the predicted MT2816/Rv2745c DNA-binding protein in S. coelicolor and C. glutamicum act as regulators of clp genes [36, 37]. The expression of MT2816/Rv2745c is induced during redox [16] and SDS [18] stress in Mtb. It is also co-expressed with σH and σE during enduring hypoxia [38]. Clearly, the MT2816/Rv2745c encoded protein plays an important role in stress response. To better understand the regulation of MT2816/Rv2745c, we studied its expression in wild-type Mtb, the Δ−σH mutant and the Δ−σE mutants, during normal and stress conditions. Simultaneously, the expression of σH, σE and σB was studied, in order to help pin-point the role played by each of these factors, in the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c.

MT2816/Rv2745c was co-expressed with σH, σE and σB in Mtb, during diamide (Fig. 1A-D), heat (Fig. 1E-H) and SDS (Fig. 1I & 1J) stress. This is mostly consistent with our current understanding, with the exception of the fact that we observed a slight but significant induction in the levels of σH following SDS stress in Mtb. The absolute levels of MT2816/Rv2745c and all three σ factors following SDS stress were significantly lower than those obtained for diamide and heat stress.

These results show that the presence of σH is necessary for the optimal induction of MT2816/Rv2745c in MtbThe expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was either not induced, or induced at significantly lesser levels following these stress conditions, in the Δ−σH mutant. On the other hand, the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was reduced in the Δ−σE mutant compated to Mtb. It is likely that at least in the conditions studied here, the expression of σH (which is functional in the Δ−σE mutant) allowed optimal expression of MT2816/Rv2745c in the Δ−σE mutant. This indicates that the observed induction of σE during the conditions studied here may be an indirect affect of the induction of σH. On the other hand, based on these results, it appears that σB is also directly induced following certain stress conditions, e.g. heat and acid-shock, in addition to its σH and σE dependent induction. The levels of MT2816/Rv2745c did not increase under many stress conditions (Fig. 2A-D, 2G-H, 3A-D). This indicates that non-specific oxidative stress or damage to the Mtb cell-wall is insufficient to induce the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c. Induction of MT2816/Rv2745c is absolutely linked to the activation of a network (σH/σE/σB) of σ factors. This is supported by the co-expression of MT2816/Rv2745c, σH and σE during diamide [16, this study] and SDS stress [7, this study] and enduring hypoxia [38]. Further, the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c was induced at low pH. This is not surprising, since the expression of σH has been shown to increase in Mtb during acid-shock [13]. Finally, our experiments with Mtb-infected primate BMD phagocytes indicate that the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c and the σH/σE/σB network occurs during infection. This result raises the prospect that MT2816/Rv2745c encoded protein is required by Mtb to manage host-derived stress during infection.

Treatment of Mtb with vancomycin, a drug which targets bacterial cell-wall, induces the expression of MT2816/Rv2745c [25]. We have recently shown that THZ, which also induced MT2816/Rv2745c expression, damages Mtb cell-wall [Dutta NK, Mehra S, Kaushal D, 09-PONE-RA-14357R1, in revision]. Stress caused by damage to Mtb cell-wall may decrease proton-motive force [25]. MT2816/Rv2745c may help stabilize the cell-wall in response to this damage. The genes induced by MT2816/Rv2745c encode cytochrome oxidase, mycothiol glycosyltransferase, ferridoxin C, an allosteric modulator of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, ribulose-phosphate epimerase, malate dehydrogenase and various other dehydrogenases. This result indicates that the cellular redox potential and energy stores are depleted following stress conditions, likely due to membrane damage. Gene-expression reprogramming by MT2816/Rv2745c attempts to restore this redox potential. This explains the induction of MT2816/Rv2745c, in response to THZ, a drug that disrupts bacterial redox potential by inactivating NADH dehydrogenase [31, 32]. The expression of menaquinone synthesis genes (menA, menB) was significantly repressed following MT2816/Rv2745c over-expression. Menaquinone synthesis has been implicated in electron transport during nonreplicative persistence, and the significance of its repression by this regulator is currently not understood by us.

Of particular interest was the induction of otsA, which codes for trehalose-phosphate synthase. This gene is a member of the dominant biosynthetic pathway for trehalose, a disaccharide constituent of cell-wall glycolipids. Trehalose plays an important role in cell-wall biogenesis, and also acts as a defense mechanism for surface and oxidative stress. Due to its absence from mammalian cells, and the central importance of the Mtb cell-wall to the pathogen's survival, trehalose biosynthesis and its regulators are excellent targets of anti-tubercular drug development.

The expression of Rv1425, encoding triacylglycerol synthase was also induced. Mtb may utilize triacylglycerols to overcome the damage to cell-wall. The expression of protein kinase PknD, which phosphorylates and influences the activity of the anti-anti-σF [39], was also induced. The expression of a cAMP receptor transcription factor, Rv3676, and rpfA, a gene which codes for resuscitation promotion factor and which is dependent on Rv3676 for its expression [40], were both induced by MT2816/Rv2745c.

While the two genes neighboring MT2816/Rv2745c (Rv2744c and Rv2743c) show diminished expression following the induction of this regulator, we don't believe that MT2816/Rv2745c encoded protein is a repressor of its own operon. The concomitant induction of these three genes has been shown following SDS stress [20], as well as following THZ treatment of Mtb [Dutta NK, Mehra S, Kaushal D, 09-PONE-RA-14357R1, in revision]. It is possible that in the absence of actual stress, a negative feedback regulatory switch controls the induction of this operon.

MT2816/Rv2745c, an important stress-response factor of Mtb, is induced in response to a diverse range of environmental cues. Our results raise the possibility that modulation of gene-expression by MT2816/Rv2745c may help Mtb survive in the face of in-vivo stress mimicked by these in-vitro conditions. In future, we will study the role of MT2816/Rv2745c by studying the phenotype of its conditional mutant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R21RR026006 (DK), P20RR020159 and P51RR164. In addition, awards from Tulane Research Enhancement Fund (DK), Louisiana Vaccine Center/Louisiana Board of Regents (DK), and Tulane Center for Infectious Diseases (SM, NKD) are sincerely acknowledged. Assistance by Avery MacLean (secretarial) and Robin Rodriguez (graphic design) is gratefully acknowledged. We especially thank Prof. Stefan HE Kaufmann, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany, for allowing access to high quality Mtb microarrays. We also gratefully acknowledge the kind gift of tetracycline promoter containing vector pSE100, by Dr. Sabine Ehrt, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Abbreviations

- TB

Tuberculosis

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- σ

sigma

- THZ

Thioridazine

- INH

Isoniazid

- ETMB

Ethambutol

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in connection with this manuscript.

Author contributions: Funding – DK; research design – SM and DK; research – SM, NKD; data analysis – SM and DK; critical reagents – H-JM; Writing – DK with help from SM.

References

- 1.Raviglione MC. The TB epidemic from 1992 to 2002. Tuberculosis. 2003;83:4–14. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen P, Doherty TM. The success and failure of BCG - implications for a novel tuberculosis vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:656–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matteelli A, Migliori GB, Cirillo D, et al. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: epidemiology and control. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2007;5:857–71. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross CA. The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3843–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Missiakas D, Raina S. The extracytoplasmic function sigma factors: role and regulation. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1059–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez JE, Chen JM, Bishai WR. Sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:175–83. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontan PA, Aris V, Alvarez ME, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigma factor E regulon modulates the host inflammatory response. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:877–85. doi: 10.1086/591098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaushal D, Schroeder BG, Tyagi S, et al. Reduced immunopathology and mortality despite tissue persistence in a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking alternative sigma factor, SigH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8330–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102055799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, Karakousis PC, Bishai WR. Roles of SigB and SigF in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigma factor network. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:699–707. doi: 10.1128/JB.01273-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manganelli R, Voskuil MI, Schoolnik GK, et al. Role of the extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor sigma(H) in Mycobacterium tuberculosis global gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:365–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohno H, Zhu G, Mohan VP, et al. The effects of reactive nitrogen intermediates on gene expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:637–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham JE, Clark-Curtiss JE. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNAs synthesized in response to phagocytosis by human macrophages by selective capture of transcribed sequences (SCOTS) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:11554–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohde KH, Abramovitch RB, Russell DG. Mycobacterium tuberculosis invasion of macrophages: linking bacterial gene expression to environmental cues. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:352–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song T, Dove SL, Lee KH, Husson RN. RshA, an anti-sigma factor that regulates the activity of the mycobacterial stress response sigma factor SigH. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:949–959. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park ST, Kang CM, Husson RN. Regulation of the SigH stress response regulon by an essential protein kinase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13105–13110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801143105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehra S, Kaushal D. Functional genomics reveals extended roles of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis stress response factor σH. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3965–80. doi: 10.1128/JB.00064-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen-Cain DM, Quinn FD. Differential expression of sigE by Mycobacterium tuberculosis during intracellular growth. Microb Path. 2001;30:271–278. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2001.0431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manganelli R, Voskuil MI, Schoolnik GK, Smith I. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis ECF sigma factor sigmaE: role in global gene expression and survival in macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:423–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ando M, Yoshimatsu T, Ko C, Converse PJ, Bishai WR. Deletion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis sigma factor E results in delayed time to death with bacterial persistence in the lungs of aerosol-infected mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:7170–7172. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.7170-7172.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manganelli R, Fattorini L, Tan D, et al. The extra cytoplasmic function sigma factor σE is essential for Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence in mice. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3038–3041. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.3038-3041.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He H, Hovey R, Kane J, Singh V, Zahrt TC. MprAB is a stress-responsive two-component system that directly regulates expression of sigma factors SigB and SigE. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2134–2143. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2134-2143.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pang X, Vu P, Byrd TF, et al. Evidence for complex interactions of stress-associated regulons in an mprAB deletion mutant of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. 2007;153:1229–1242. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dona V, Rodrigue S, Dainese E, et al. Evidence of complex transcriptional, translational and post-translational regulation of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σE in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5963–5971. doi: 10.1128/JB.00622-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barik S, Sureka K, Mukherjee P, Basu J, Kundu M. RseA, the SigE specific anti-sigma factor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is inactivated by phosphorylation-dependent ClpC1P2 proteolysis. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:592–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Provvedi R, Boldrin F, Falciani F, Palu G, Manganelli R. Global transcriptional response to vancomycin in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. 2009;155:1093–102. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.024802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betts JC, Lukey PT, Robb LC, McAdam RA, Duncan K. Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:717–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geiman DE, Raghunand TE, Agarwal N, Bishai WR. Differential Gene Expression in Response to Exposure to Antimycobacterial Agents and Other Stress Conditions among Seven Mycobacterium tuberculosis whiB-Like Genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemo. 2006;50:2836–2841. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00295-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butcher PD, Mangan JA, Monahan IM. Intracellular gene expression: analysis of RNA from mycobacteria in macrophages using RT-PCR. In: Parish T, Stoker NG, editors. Meth Mol Biol Mycobacteria Protocols. Vol. 101. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 285–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehrt S, Guo XV, Hickey CM, et al. Controlling gene expression in mycobacteria with anhydrotetracycline and Tet repressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart GR, Wernisch L, Stabler R, et al. Dissection of the heat-shock response in Mycobacterium tuberculosis using mutants and microarrays. Microbiol. 2002;148:3129–38. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boshoff HI, Myers TG, Copp BR, et al. The transcriptional responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to inhibitors of metabolism: novel insights into drug mechanisms of action. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40174–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao SP, Alonso S, Rand L, Dick T, Pethe K, Rao SP, Alonso S, Rand L, Dick T, Pethe K. The protonmotive force is required for maintaining ATP homeostasis and viability of hypoxic, nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11945–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Capuano SV, 3rd, Croix DA, Pawar S, et al. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5831–44. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5831-5844.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutta NK, Mehra S, Didier PJ, et al. Genetic requirements for the survival of tubercle bacilli in primates. J Infect Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1086/652497. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manganelli R, Provvedi R, Rodrigue S, et al. Sigma factors and global gene regulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:895–902. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.4.895-902.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellier A, Mazodier P. ClgR, a novel regulator of clp and lon expression in Streptomyces. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3238–48. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.3238-3248.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engels S, Schweitzer JE, Ludwig C, et al. clpC and clpP1P2 gene expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum is controlled by a regulatory network involving the transcriptional regulators ClgR and HspR as well as the ECF sigma factor sigmaH. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:285–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rustad TR, Harrell MI, Liao R, Sherman DR. The enduring hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenstein AE, MacGurn JA, Baer CE, et al. M. tuberculosis Ser/Thr protein kinase D phosphorylates an anti-anti-sigma factor homolog. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e49. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rickman L, Scott C, Hunt DM, et al. A member of the cAMP receptor protein family of transcription regulators in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for virulence in mice and controls transcription of the rpfA gene coding for a resuscitation promoting factor. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1274–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.