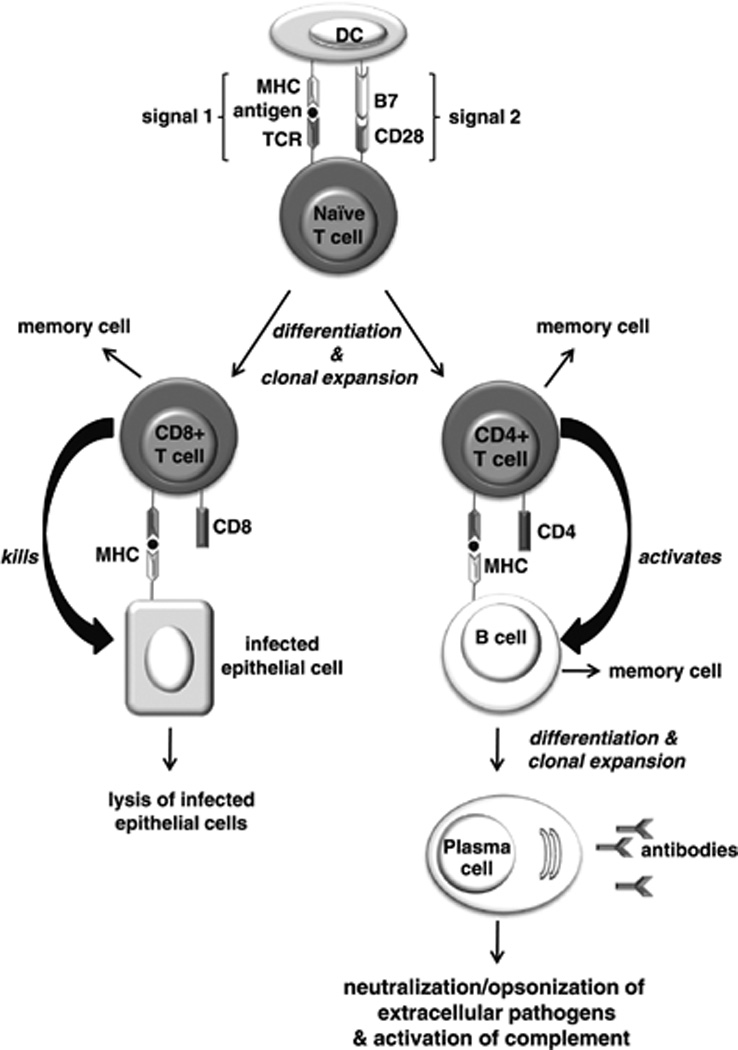

Figure 1.

Induction of a primary adaptive immune response. Antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells (DCs) take up pathogens and present the pathogen antigens to naïve T cells. Those T cells that bear a T-cell receptor (TCR) specific for the antigen presented undergo clonal expansion and differentiate into CD8+ and CD4+ effector T cells. For this to occur, the T cell must receive two signals from the DC. Signal 1 is delivered by the interaction of the TCR with the antigen/ major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on the DC. Signal 2 is delivered upon binding of the B7 molecule on the DC to the CD28 receptor on the T cell. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells recognize the antigen/MHC complex on the surface of cells, and are activated to destroy the infected cells. Naïve B cells bearing immunoglobulin receptors specific for the antigen internalize the antigen and present it to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, which in turn induce the B cells to clonally expand and differentiate into antibody-producing plasma cells. The antibodies produced target extracellular pathogens and their toxic products via the processes of neutralization, opsonization, or complement activation. A small proportion of activated T and B cells form long-lived memory cells, which are responsible for mounting a stronger, secondary immune response upon subsequent encounters with their cognate antigen.