Abstract

This study was designed to test the effectiveness of the dual process model (DPM) of coping with bereavement. The sample consisted of 298 recently widowed women (61%) and men age 50+ who participated in 14 weekly intervention sessions and also completed before (O1) and after (O2) self-administered questionnaires. While the study also includes two additional follow-up assessments (O3 and O4) that cover up to 14-16 months bereaved this paper examines only O1 and O2 assessments. Based on random assignment, 128 persons attended traditional grief groups that focused on loss-orientation (LO) in the model and 170 persons participated in groups receiving both the LO and restoration-orientation (RO) coping (learning daily life skills). As expected, participants in DPM groups showed slightly higher use of RO coping initially, but compared with LO group participants they improved at similar levels and reported similar high degrees of satisfaction with their participation (i.e. having their needs met and 98-100% indicating they were glad they participated. Even though DPM participants had six fewer LO sessions, they showed similar levels of LO improvement. Qualitative data indicate that the RO component of the DPM might be more effective if it is tailored and delivered individually.

In this article, we present and describe the preliminary results of our intervention study based on the Dual Process Model (DPM) of coping with bereavement (Stroebe & Schut, 1999). Our study compared the experiences of recently bereaved men and women age 50+ who received both of the DPM features (i.e. loss-orientation [LO] and restoration-orientation [RO]) with others in a comparison group who received only the LO features in their intervention. There are three primary purposes of this article. First, we describe and compare the experiences and evaluations of those recently bereaved spouses/partners who participated in the two group conditions described above. Second, we examine the extent to which the LO and RO coping processes were enhanced by participating in each of the two study conditions, DPM treatment versus the comparison group. Third, and based on the findings of the above, we identify the most valuable and promising features of the DPM intervention for future research and practice.

While other articles in this special issue deal with different populations of bereaved persons we focused exclusively with recently widowed men and women age 50+ regardless of the level of early coping difficulty. In other words, we did not select only those who were experiencing complicated or traumatic grief. Rather, we wanted to test the DPM with a broad representation of bereaved persons in mid and later life. Furthermore, although the larger study was designed to test the effectiveness of both study conditions in terms of various bereavement adjustment outcomes over time, these data will be analyzed in future manuscripts. Therefore, this report is focused on the early coping processes targeted by the intervention. The DPM describes loss-orientation and restoration-orientation as coping responses to two primary types of stressors that bereaved persons experience with each type of stress requiring specific types of coping behaviors and strategies. These processes, in turn, influence bereavement adjustment outcomes related to well-being.

Background on Spouse/Partner Bereavement

The consequences of spousal/partner loss in later life have been well documented (Bennett et al., 2005; Bisconti et al., 2004; Carr et al., 2006; Hansson & Stroebe, 2007; Lee & Carr, 2007; Lund, 1989; Lund & Caserta, 2002; Stroebe et al., 1993). Although the long-term bereavement process is experienced with considerable variability, some common elements have included profound sadness, pining, depression, altered identity, negative health outcomes, loneliness and the withdrawal of support networks. Additionally, there is evidence of considerable stress associated with the role changes that accompany widowhood, particularly those due to disruptions in life patterns and daily routine, taking on new unfamiliar tasks, and changes in social activities and relationships (Anderson & Dimond, 1995; Carr, 2004; Moss et al., 2001; Utz et al., 2002; Utz et al., 2004). Persons overwhelmed or preoccupied with grief often neglect their own nutrition, fail to exercise regularly, discontinue physical and social activities that they previously did as a married couple, and become more accident prone from paying less attention to their personal safety (Johnson, 2002; Quandt et al., 2000; Schone & Weinick, 1998; Shahar et al., 2001). The loss of a spouse or partner can be disruptive to existing health care practices, as well as interfere with the adoption of new healthy behaviors (Chen et al., 2005; Pienta & Franks, 2006; Powers & Wampold, 1994; Rosenbloom & Whittington, 1993; Williams, 2004).

Spouse/partner bereavement can adversely impact the performance of daily living tasks that are essential for health and independent functioning. For example, meal planning and preparation, household maintenance, managing finances, as well as other tasks often go unattended by the surviving spouse if these tasks were primarily the responsibility of his or her deceased partner. Those who fail to acquire new skills to accomplish these tasks are at increased risk for long-term mental and physical health problems following widowhood (Carr et al., 2000; Lund, Caserta, Dimond et al., 1989; Stroebe & Schut, 1999; Utz, 2006; Wells & Kendig, 1997).

While spouse or partner loss is often associated with a variety of disruptive and negative outcomes, research and theory also has focused on successful adaptation, resiliency and personal growth among the bereaved (Boerner et al., 2005; Bonanno, 2004; Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006; Caserta et al., 2009; Dutton & Zisook, 2005; Lund et al., 2008; Montpetit et al., 2006; O’Rourke, 2004; Ong & Bergeman, 2004; Ong et al., 2004; Wilcox et al., 2003; Znoj, 2006). Several conceptual models have emerged to describe these disruptive processes and outcomes—most notably Worden’s (2002) “tasks of grief” and other more general stress and coping models (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). These approaches, however, pay little attention to other concurrent restorative processes (i.e. in addition to the LO processes) and potential positive consequences like opportunities for personal growth through learning, having new experiences and helping others (Doka & Martin, 2001; Lund, 1999; Lund et al., 2008).

Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement

The Dual Process Model (DPM) of coping with bereavement (Stroebe & Schut, 1999) has emerged as a response to the limitations associated with earlier conceptual frameworks. While the first article in this special issue of Omega (Stroebe & Schut; in press) presents an overview of and the latest developments regarding the DPM (Stroebe & Schut, 1999), we provide a description of the key elements of the model, with particular attention to how it guided the development of our intervention and influenced the selection of our process and outcome measures.

The DPM identifies two concurrent types of stressors and coping processes. First, loss-orientation (LO) refers to the coping processes (including grief work) directly focused on the stress attributed to the loss itself, encompassing many of the grief-related feelings and behaviors that tend to dominate early but can re-emerge later and sporadically in the bereavement process. Second, restoration-orientation (RO) refers to those processes the bereaved use to cope with the secondary stressors that accompany new roles, identities, and challenges related to the new status as a widow, widower or bereaved partner. These often include the need to master new tasks, make important decisions, meet new role expectations, and take greater self-care initiative. If RO progresses effectively, self-efficacy beliefs emerge and help facilitate greater confidence, independence, and autonomy needed to manage their daily lives (Caserta, 2003; Lund & Caserta, 2002; Utz, 2006). Another desired outcome is a sense of personal growth as a result of becoming more independent and learning new skills (Calhoun & Tedeschi, 2006; Caserta et al, 2009; Dutton & Zisook, 2005; Schaefer & Moos, 2001).

Another feature of the DPM is the need to take brief periods of respite from grieving itself, whether to address these new tasks or demands or to keep busy with diversionary or meaningful activities to help restore a sense of balance and well-being. There is evidence that engaging in physical activity, hobbies, volunteer projects and other leisure activities, as well as socializing and being involved with others provides an important source of restoration and respite for the bereaved As well, our previous research found a strong association between perceived competencies in tasks of daily living and more favorable adjustments to psycho-emotional aspects of grief (Lund et al., 1989). The RO coping process is amenable to intervention by focusing on self-efficacy, skills related to new unfamiliar tasks of daily living, self-care, and opportunities to engage in activities that provide brief periods of respite from grief.

What distinguishes the DPM from the other more global stress and coping frameworks is the recognition that the bereaved will oscillate between the two coping processes (RO, LO) throughout the course of bereavement as demands arise in their daily lives, even on a moment to moment basis (Caserta & Lund, 2007; Richardson & Balaswamy, 2001; Stroebe & Schut, 1999). In previous research, we identified and described several potentially important dimensions of “oscillation” (Caserta & Lund, 2007), including the degree of balance, frequency, awareness, control and intent of oscillation.

Although there have been exceptions (Caserta, Lund, & Obray, 2004; Caserta, Lund, & Rice, 1999), most of the previous and current bereavement interventions focus primarily on emotional impacts of the loss itself (LO) and have rarely addressed the concurrent RO issues that the bereaved confront in their daily lives. Our intervention, based on the DPM provides coping assistance directed at both the LO and RO components and encourages the oscillation between them by alternating attention to them in group sessions/meetings.

The DPM-Based Intervention

We refer to this study as the “Living After Loss” (LAL) project; the name was chosen as a way to identify the program to the research participants and community professionals without sounding too academic or theoretical. We designed the LAL study specifically to compare a DPM-based intervention (with both the LO and RO components) with the traditional support group format as the comparison group (which provides attention primarily to LO coping processes). We hypothesized that those in the DPM condition would have more positive and broadly based coping processes and outcomes than those who were in the LO only comparison condition. Our present analyses are focused on the DPM coping processes and not on the adjustment outcomes as those data are not yet available. Both the DPM and comparison conditions consisted of 14 weekly sessions, each about 90 minutes in length. Those in the DPM group had seven of 14 sessions devoted to RO issues, whereas all 14 sessions within the comparison group were solely loss-oriented in focus. The RO-focused sessions of the DPM condition were alternated with the LO-focused sessions to simulate the oscillation between the LO and RO coping processes. For those in the DPM groups, they had fewer LO sessions but the content for these sessions was the same as those in the LO only comparison groups. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the content and theoretical principles addressed in each of the 14 weekly sessions of the DPM intervention. Additional details about the intervention content and format are available upon request to the first author and/or in another publication (Lund, Caserta, de Vries and Wright, 2004).

Table 1. Description of the 14-Week Dual Process Model (DPM) Intervention.

| Session | Content | Link to Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LO |

|

|

| 2, 3 | LO |

|

|

| 4 | LO |

|

|

| 5 | RO |

Goal Setting & Personal Priorities

|

|

| 6 | LO |

|

|

| 7 | RO |

Self-Care & Health Care

|

|

| 8 | LO |

|

|

| 9 | RO |

Finances and Legal Issues

|

|

| 10 | LO |

|

|

| 11 | RO |

Household and Vehicle Responsibilities

|

|

| 12 | RO |

Nutrition for One

|

|

| 13 | RO |

Remaining Socially Connected

|

|

| 14 | LO-RO |

|

|

LO = Loss-Oriented

RO = Restoration-Oriented

Research Design and Sampling Procedures

Eligibility for the LAL project was restricted to widowed persons age 50 and older, whose spouse or partner had died within the previous 2-6 months, who were English speaking, and who were cognitively and physically able to complete questionnaires and participate in a 14-week group meeting. Participants also had to reside in one of the two study areas (San Francisco or Salt Lake City) for the duration of the group intervention. Potential participants were identified from death certificate data filed with local and federal health agencies. Names and addresses of the surviving spouses or partners, as well as information on the decedent, were included on the death records.

Potential participants received an invitation letter roughly three months prior to the commencement of the groups. Then, approximately 5-7 days after the letters were mailed, a trained research assistant contacted them by telephone. The purpose of the call was to verify that they received the letter, that they met the study criteria, to address any questions about the study, and to solicit their preliminary agreement to participate. Those who were ineligible or not interested in participating received a list of available community-based resources related to bereavement. If all the eligibility criteria were met and the potential participant agreed, the RA made an appointment to conduct a home visit, in which informed consent was obtained and the baseline (O1) questionnaire was left for the participant to complete. Participants were randomly assigned in equivalent proportions to one of the two group interventions (DPM or Comparison).

All participants, regardless of their assigned study condition, completed self-administered questionnaires largely consisting of background information and a variety of measures commonly used in bereavement research: Baseline (O1) data were collected prior to the intervention at 2-6 months of bereavement. Post-test (O2) occurred at the conclusion of the 14-week intervention period (at 5 to 9 months of bereavement) with the O3 assessment following 3 months later. The final data point (O4) was 6 months following O3, equivalent to 14-18 months after the loss. Participants received $25 per questionnaire, for a total of $100 if they completed all four waves of data collection. The average participant completed the O1 baseline questionnaire approximately 4 months (15.7 weeks) after the spouse’s death, with some completing it as early as 5 weeks post-loss and some as late as 24 weeks post-loss. The group intervention commenced approximately 4.7 months post-loss, with a range of 2 to 7.5 months bereaved.

Sample

A total of 328 widowed persons completed O1 questionnaires, but the analytic sample for this report includes the 298 participants who completed both the O1 (pre-test) and O2 (first post-intervention assessment). The most common reasons for attrition between O1 and O2 included: “I decided that the group was not for me,” “My grief is too strong and I am unable to participate in group,” or the participant decided that they “no longer wanted to participate in LAL” without specifying a reason. One participant died after he completed the baseline questionnaire, but before the groups started. Two participants experienced significant health declines just prior to the start of the group intervention, and a few others had to withdraw in order to take care of unexpected family emergencies. Finally, the group leaders discovered that a few of the enrolled participants were not suitable for the group intervention, due to cognitive impairment or significant hearing loss; they were asked to withdraw from the study.

Our analytic sample includes 61% women (n = 183) and 39% men (n = 115). The average age of our sample was 69.5 years (SD = 10.6), with a range of 50 to 93 years. Participants had been married or partnered for an average of 40.1 years (SD = 17.0). Our sample was quite educated: only 14% of the sample had a high school education or less; 41% had some college; and 45% had graduated from a college. The majority were Caucasian (87%), with 6% Asian, 4 % African American, 2%, Latino and 1% other. Also, 10 participants or 3% of the sample had been in a same-sex union. A little more than half (58%) said they expected the spouse’s death. Regarding financial status, 69% reported that they were “comfortable”, 17% said “more than adequate” and 14% said that it was “not very good”. A little more than half of the participants (n=170 or 57%) were assigned to the DPM condition, while 128 or 43% were assigned to the LO condition. The number of weekly intervention sessions attended was the same for those in the LO and DPM conditions, with an average of 11.03 sessions (SD=3.3).

Measures

DPM coping processes were measured by the Inventory of Daily Widowed Life [IDWL – (Caserta & Lund, 2007)], consisting of 22 Likert-format items that inquire into how much time during the past week the respondents spent on loss-oriented activities (e.g., “Thinking about how much I miss my spouse;” “Feeling a bond with my spouse”) and restoration-oriented activities (e. g., “Finding ways to keep busy or occupied;” “Took some time away from grieving for my spouse”). Eleven loss-orientation items and 11 restoration-orientation items were identified largely from Stroebe and Schut’s (1999) description of the types of instances that would fall into each category. Construct validity has been established for both subscales (Caserta & Lund, 2007). LO and RO subscale scores were calculated by summing the identified items (on scales from 1 “rarely or not at all” to 4 “almost always,” each subscale ranging from 11 to 44), with lower scores indicating less LO or RO coping and higher scores indicating more LO or RO coping. Both subscales range from 11 to 44 and have high internal consistency (LO subscale, alpha = .91; RO subscale, alpha = .73).

Oscillation balance or the degree to which the participants engaged in equal amounts of both processes was calculated by subtracting their total LO score from their total RO score (RO minus LO). Hence, the balance score can range from −33 (exclusively loss-orientation focus) to +33 (exclusively focused on restoration-orientation). A score equal to 0 indicates perfect balance between the two processes.

In addition to examining the extent to which the participants were engaging in loss- and restoration-oriented coping processes, we also were interested in knowing to what extent they were consciously aware of where they were focusing their attention. Consequently, the participants were requested to respond to two additional items that asked, “During the past week, to what extent have you focused your attention on issues related to grief, emotions and feelings regarding your loss?” to measure if they were aware of their engagement in loss-orientation, and to what extent they focused on “new responsibilities, activities, and time away from grieving” as a way to measure awareness of their own restoration-oriented coping. Both items were measured on a scale from 1-5 with 1 indicating very little and 5 a great deal.

Participants’ Assessment of Group Sessions

At the O2 measurement, the participants completed a series of items that inquired into how well they believe they learned or understood each of the topics covered in the group meetings (ranging from 1 [not at all well] to 5 [very well]) and to what extent they were applying what they learned in their daily lives (1 = not at all; 5 = almost always). Each of the items corresponded to the content depicted in Table 1. There were 11 items related to loss-oriented aspects of coping with grief and loss that were completed by participants in both study conditions. Those in the DPM treatment group completed 11 additional items that represented the content addressed in the seven RO sessions. The participants also completed a checklist to indicate if they sought additional information outside the group meetings on any of the topics that were covered in their weekly sessions as well as an open-ended item where they were given the opportunity to identify any topics they wish were addressed but were not. We also compared the participants in both groups on items related to their motivation to attend group meetings (ranging from 1 = very little to 5 = very much), the extent to which their needs were met by their participation (ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = very well), and whether or not they were glad they had participated (yes or no).

Results

Participants’ Assessment of Their Group Experiences and Content Exposure

Our first interest was in identifying how well participants learned or understood and were applying in their daily lives those intervention topics related to grief (LO sessions). We also compared the responses of participants in both study conditions. There were no statistically significant differences between DPM and comparison participants on their assessments of grief-related topics. The top five grief topics (based on 1-5 ratings) for “how much was learned” for both the DPM and LO participants were in the same rank order and with mean scores ranging from 4.0 to 4.5. They were: 1) Experience of grief is unique to each person, 2) Understanding the need to grieve, 3) How grief affects everyday functioning, 4) Understanding what grief is, and 5) Expectations about how and when to grieve. With respect to how much they were applying what they learned in their daily lives, participants in both study conditions had the same top five answers (based on 1-5 ratings) and nearly in the same order with the highest ones being “Experiences of grief is unique”, “Understanding the need to grieve”, “Using humor as a way to cope with loss”, “How grief affects everyday functioning” and “Dealing with challenges assuming new responsibilities”. The mean scores on these items ranged from 3.8 (new responsibilities) to 4.2 (grief is unique).

Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were found between those in the two study conditions regarding their motivation to attend meetings or the percentages reporting they were glad they participated. Most participants had very favorable ratings of the program. Regarding motivation for attending, both groups had mean scores of 4.2 (1-5 scales). Ninety-nine percent of those in the comparison condition and 95% in the DPM condition said they were glad they participated. In short, there were far more similarities between those in the DPM and comparison group condition than there were differences and most participants, regardless of group condition, were very favorable about what they had learned and were applying, their motivation levels to attend meetings, and being glad they had participated.

For those in the DPM condition, the top five restoration-oriented skills that they learned and applied in their daily lives were the same. The highest rated RO topic was “Taking responsibility for health needs” followed by “Maintaining clean and safe home”, “Keeping home and auto in good repair”, “Avoiding scams and fraud”, and “Managing finances and budget”. Participants gave average ratings ranging from 4.1 to 4.2 on all five of these topics. Two other skill topics with high scores for “what was learned” included “Nutrition for one” and “Insurance and legal matters”. There were eight RO skill topics for which notable proportions of DPM participants indicated they sought additional information beyond what they learned in the group sessions. These were “Insurance and legal matters” (35%), “Taking responsibility for health needs” (29%), “Setting personal goals” (29%), “Managing finances and budget” (27%), “Trying new things” (27%), “Nutrition for one” (24%), “Leisure, social and volunteer activities” (24%), and “Keeping home and auto in good repair” (23%). One interpretation of these data is that the RO sessions stimulated the interest of many participants in these topics as well as many persons recognized the need for them to learn more than what could be covered during the sessions.

The participants also were asked, “Are there any topics you wish were covered but were not?” Very few comparison group participants indicated whether there was anything about which they would have liked to learn more but those in DPM groups gave many suggestions, including learning about new relationships, sprinkling systems, hobbies, driving, computers, cooking, books, making television recordings, working cameras, art and spiritual issues. These responses might suggest that having participated in RO types of group sessions during the intervention stimulated their thinking about other topics and skills of interest which would be a positive outcome according to the Dual Process Model.

Participants’ Engagement in LO and RO Coping Process

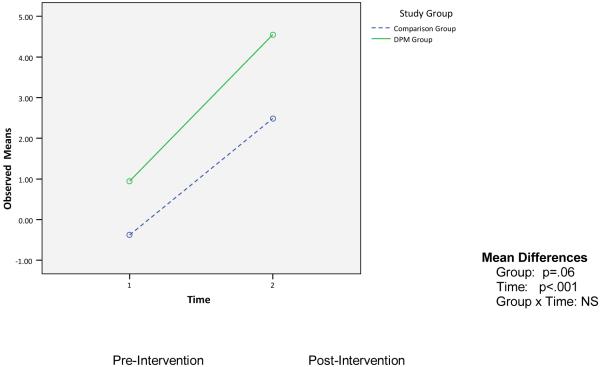

Our next interest was to examine the extent to which the DPM intervention was enhancing LO and RO coping processes by comparing the participants in the DPM condition with those in the comparison group. Recall, that we expected those in both study groups to be similar to each other regarding LO coping from O1 (prior to the intervention) to O2 (assessed within 2-4 weeks after the intervention) because all participants received intervention content devoted to LO coping. However, we expected those in the DPM condition to show greater gains in RO coping because the comparison group focused on loss-oriented issues without any deliberate attempt to foster restoration-orientation. Figure 1 shows the mean scores for both study groups at O1 and O2 using the IDWL subscales described earlier. The mean scores for both groups show a statistically significant decline in LO coping from O1 to O2 (p < .001) which is consistent with the Dual Process Model in that LO coping gradually subsides while RO coping tends to increase over time. The decline in LO coping, however, was independent of study condition as indicated by the failure of the group by time interaction to attain statistical significance. This could be interpreted as a positive outcome of the DPM intervention in that similar decrements were noted regarding LO coping even though DPM participants received overall less attention in their intervention to LO coping because they had fewer sessions devoted to those issues.

Figure 1. Pre- and Post-Intervention Measures of Loss-Oriented Coping by Study Group.

Loss-Oriented Coping is measured with an 11-item scale (range 11 to 44). Lower values indicate less loss-oriented coping.

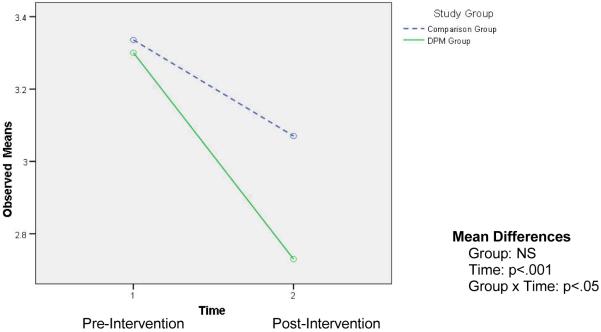

Figure 2 shows the mean scores for the two study conditions regarding O1 to O2 changes in RO coping. Those who were in the DPM condition were expected to show greater gains in RO coping than the comparison group condition because they had half of their intervention sessions devoted to restoration-oriented issues. The data show that while those in the DPM condition did show greater gains in RO coping, those in the comparison group showed some gains as well. Therefore, both groups changed over time (p < .05) but there was no statistically significant group by time effect.

Figure 2. Pre- and Post-Intervention Measures of Restoration-Oriented Coping by Study Group.

Restoration-Oriented Coping is measured with an 11-item scale (range 11 to 44). Lower values indicate less restoration-oriented coping.

The overall decline in the use of LO coping and increase use of RO coping among the participants is further reflected in the change in oscillation balance scores from O1 to O2, illustrated in Figure 3. Participants in both groups were fairly balanced between both processes at baseline but moved to a greater focus on restoration-oriented coping by the time the weekly sessions ended (p < .001). Although mean balance scores at O2 were further away from zero than they were at the baseline assessment, the score values were of a magnitude that indicates that loss-oriented coping was still occurring at O2 for participants in both study conditions. At the same time, a trend appeared to be emerging (although not statistically significant) in which those in the DPM condition were beginning to invest more effort into RO (versus LO) coping, than the comparison group.

Figure 3. Pre- and Post-Intervention Measures of Oscillation Balance by Study Group.

Oscillation balance is measured by ....., with responses ranging from … to ....

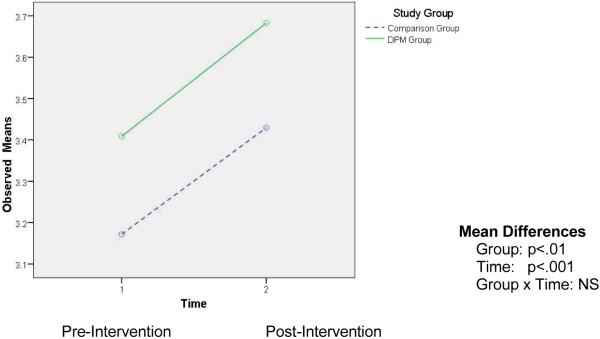

Figure 4 shows that those in both group conditions had similar LO coping awareness scores at O1, and consistent with the model were consciously aware that they were devoting less attention to loss-oriented issues by the O2 assessment. The significant group by time interaction (p < .05) however, indicates that this awareness was greater among those in the DPM treatment group. Alternatively and somewhat unexpectedly, we found that participants in both conditions were showing greater awareness of RO coping from O1 to O2. Although there is a statistically significant overall increase in RO awareness (p < .001) both groups changed in a parallel fashion (see Figure 5). It may be possible that even those in the comparison condition were learning new skills and engaging in RO coping without having intervention sessions specifically devoted to these issues. Indeed, there were informal suggestions from participants and the research assistants who attended sessions reported that, some participants encouraged each other to seek assistance with restoration-oriented activities.

Figure 4. Pre- and Post-Intervention Measures of Awareness of Loss-Oriented Coping by Study Group.

Awareness is measured with a single-item question (In the past week, to what extent have you focused your attention on issues related to grief, emotions, and feelings regarding your loss?), with responses ranging from 1 very little to 5 a great deal.

Figure 5. Pre- and Post-Intervention Measures of Awareness of Restoration-Oriented Coping by Study Group.

Awareness is measured with a single-item question (In the past week, to what extent have you focused your attention on issues related new responsibilities, activities, and time away from grieving?), with responses ranging from 1 very little to 5 a great deal.

While we expected to find stronger and more positive effects for the DPM intervention, even with using only the O1 and O2 data, the open-ended questions in the self-administered questionnaires did offer some further explanations and insights. We wanted to obtain information regarding any criticisms that the DPM participants might have had so we asked them if they had any suggestions for how we could improve on the intervention. The following quotes provide some potential reasons for why we find only modest support in favor of the DPM condition. “Some sessions of little or no value – could just give us written material”, “Guest speakers not among my needs or interests”, “Did not enjoy guest speakers, maybe use only half of the meeting time”, “Guest speakers weren’t helpful or interesting, “Some presentations/speakers did not have enough time”, “Need a doctor as a speaker”, “Some speakers communicated as though we were totally inexperienced – wrong assumptions”, “Least effective were guest speakers”, “Speakers did not have enough time – rushed and couldn’t ask questions”, “Instructors were poor use of time”, “Needed better tips on house cleaning”, “Needed more info on low cost medical insurance,” “More help with financial matters, but everyone’s situation is different”, “Needed more guest speakers”, “Less speakers”, “Ask group for other specific topics”, “More knowledgeable speakers on autos and home services”. In short, these comments suggest that providing RO coping in group situations may not be the ideal way to provide what is most needed. Some participants saw the RO sessions as disruptions to the attention to loss-oriented issues from the previous week, others were not satisfied because their individual RO needs were not met in terms of the topics selected, the levels of knowledge and/or the limited time available.

Conclusion & Discussion

There are three primary conclusions of this investigation. First, regarding nearly all measures of motivation and satisfaction with the intervention processes, individuals in both conditions were highly favorable about their participation. These participants were quite pleased with having their needs met and with what they were learning and applying to their daily lives, and were feeling glad they had participated. Although this provides satisfaction for us in the design and implementation of the intervention, it may also signal the natural benefits of group interventions and the related opportunities to speak and hear from others about the loss of a spouse or life partner.

Second, although participant satisfaction was high, we identified only modest positive support for the DPM intervention versus the traditional bereavement support format represented by the comparison group condition. Those in both study conditions were engaging in similar LO coping even though the DPM group had fewer sessions devoted to it. However, although engagement in LO coping was similar for both groups, those in the DPM condition more consciously perceived themselves as engaging in less LO coping by the time the weekly sessions ended compared to those in the comparison group. Also, it appears that the comparison group participants were engaging in some RO coping even though they were not receiving an intervention targeted toward those processes. It is possible they could have learned new skills, for instance, from other sources like friends, family members, or elsewhere in the community, perhaps out of necessity (Lund et al, 1989; Utz, 2006). In a few instances as well, our group leaders occasionally reported to us that restoration-oriented issues were unintentionally raised at times by comparison group participants in the course of the weekly sessions. This potentially initiated some group discussion related to any issue that was raised as well as attention to restoration-oriented activity on the part of some outside the context of the group. Consequently, people in both group conditions were improving with respect to LO and RO coping from O1 to O2. This could suggest that nearly all bereaved persons might eventually deal with restoration-oriented stressors and engage in some restoration-oriented coping.

The above conclusion is particularly interesting in light of how the sessions were sequenced within the DPM treatment group. Focusing the early sessions on loss-orientation and the latter ones on restoration-orientation was intended to approximate the intent of the dual process model (Stroebe & Schut, 1999). We now recognize, however, that this a potentially artificial approximation as it appears that RO does tend to occur to some extent early on. Furthermore, our recent work with the IDWL suggested that in some instances an “unbalanced” oscillation favoring greater restoration-orientation, independent of how long one was bereaved, was associated with better outcomes. A greater emphasis on RO was not equivalent with avoidance in that grief, depression and loneliness levels tended to be lower when this occurred (Caserta & Lund, 2007). Consequently, we argue that how much emphasis on both LO and RO processes is optimal throughout the bereavement trajectory still needs to be investigated and developed further. While we hope to begin to address this as we examine the long-term impact of the DPM treatment on outcomes, we believe that future intervention designs, as discussed below, should consider tailoring the sequencing and content of bereavement interventions to be more responsive to the unique situations and needs of each participant. This brings us to our third primary conclusion.

While additional data and analyses are certainly needed in order to provide a more comprehensive test of the DPM intervention in terms of bereavement adjustment outcomes over time, it is clear at this point that at least some of the participants might benefit more from an individually targeted and delivered RO coping intervention. This comment is particularly supported by the open-ended data revealing the range and type of topics DPM participants identified as wanting to be covered.

There is sufficient evidence from the qualitative reports included in this article as well as from comments made from our group leaders during our project meetings when the intervention was being delivered that there were problems and limitations due to providing an RO intervention in group settings. We have learned that for some participants, they felt that the RO sessions interrupted the continuity or flow from one week’s meeting to the next. For example, when one meeting ended with a discussion of someone’s specific problem, the group was unable to continue that discussion the next week because an RO expert was scheduled to talk about an already identified RO coping topic. Also, it is clear that for some participants, the RO group sessions did not always address their most pressing needs, or specific sessions were not targeted at their specific level of knowledge or skill, or the sessions were too brief. Even preferences for speaker styles were mentioned as problematic for some participants. Our decisions about which topics to include were based on previous studies (Caserta, et al., 2004; Lund et al., 1989), but, our present intervention involves different participants with differences in specific needs.

While we remain confident that the DPM as a conceptual framework holds considerable promise for future research, education and practice, we need additional data to refine and modify the ways in which we make use of the model. It may be likely that the optimal way to deliver the RO feature is to do so with a targeted, tailored and individually delivered format so that each bereaved person identifies the RO skills that are most needed, selects the format in which they learn the new skills and in a way that fits their schedule and desired outcome with the least interference. Other bereavement researchers, educators and clinicians have suggested more individualized interventions (Breen & O’Connor, 2007; Hooyman & Kramer, 2006; Hughes, 1995; Richardson, 2007; Utz, 20062; Worden, 2002). We realize that grief support groups offer valuable opportunities to bereaved persons who like that type of format but it should be possible to provide RO interventions simultaneously to these groups and do so with more individualized formats and with more flexible sequencing.

With the addition of O3 and O4 data we will not only gain an improved understanding of how the intervention may have enhanced LO and RO coping processes, we will be able to assess the extent to which the expected changes in bereavement adjustment outcomes were achieved. Also, oscillation between the two coping processes is obviously the least well developed feature of the DPM but has considerable promise in facilitating more positive adjustment outcomes. We suggest that those who are prepared to, more aware of and able to control their oscillation will be more adaptable to meet the changing needs and demands of the complex and long-term nature of bereavement. Future interventions should be targeted toward enhancing oscillation as a coping strategy. We also remain excited about using theoretically based interventions to help those who are in the greatest need and have the most desire to receive assistance, knowing that not everyone will require sophisticated and expert interventions. We have learned that many bereaved persons are quite resilient and find ways to manage many difficult life transitions (Arbuckle & de Vries, 1995; Caserta et al., 2009; Carr, 2004; Richardson, 2007; Schaefer & Moos, 2001).

Acknowledgments

Funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG023090). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anderson KL, Dimond MF. The experience of bereavement in older adults. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995;22:308–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.22020308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle NW, de Vries B. The long-term effects of later life spousal and parental bereavement on personal functioning. The Gerontologist. 1995;35(5):637–647. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.5.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett KM, Hughes GM, Smith PT. Psychological response to later life widowhood: Coping and the effects of gender. Omega: Journal of Death & Dying. 2005;51(1):33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bisconti TL, Bergeman CS, Boker SM. Emotional well-being in recently bereaved widows: A dynamical systems approach. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2004;59B(4):P158–P167. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K, Wortman CB, Bonanno GA. Resilient or at risk? A 4-year study of older adults who initially showed high or low distress following conjugal loss. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2005;60B(2):P67–73. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.2.p67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 2004;59(1):20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen LJ, O’Connor M. The fundamental paradox in the grief literature: A critical reflection. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 2007;55(3):199–218. doi: 10.2190/OM.55.3.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: An expanded framework. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. Spousal bereavement in late life. Springer; New York, NY: 2006. Methodological issues in studying late life bereavement; pp. 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. Gender, preloss marital dependence, and older adults’ adjustment to widowhood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2004;66:220–235. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Kessler RC, Nesse R, Sonnega J, Wortman CB. Marital quality and psychological adjustment to widowhood among older adults: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;55B(4):S197–S207. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.s197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Nesse RM, Wortman CB, editors. Spousal bereavement in late life. Springer; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS. Widowers. In: Kastenbaum R, editor. Macmillan encyclopedia of death and dying. Macmillan Reference USA; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 933–938. [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS, Lund DA. Toward the development of an Inventory of Daily Widowed Life (IDWL): Guided by the dual process model of coping with bereavement. Death Studies. 2007;31(6):505–534. doi: 10.1080/07481180701356761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS, Lund DA, Obray SJ. Promoting self-care and daily living skills among older widows and widowers: Evidence from the Pathfinders demonstration project. Omega: Journal of Death & Dying. 2004;49:217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS, Lund DA, Rice SJ. Pathfinders: A self-care and health education program for older widows and widowers. The Gerontologist. 1999;39:615–620. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta MS, Lund DA, Utz R, deVries B. Stress-related growth among the recently bereaved. Aging & Mental Health. 2009;13(3):463–467. doi: 10.1080/13607860802534641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JH, Gill TM, Prigerson HG. Health behaviors associated with better quality of life for older bereaved persons. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(1):96–106. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doka KA, Martin T. Men Coping with grief. Baywood; Amityville, NY: 2001. Take it like a man: Masculine response to loss; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton YC, Zisook S. Adaptation to Bereavement. Death Studies. 2005;29(10):877–903. doi: 10.1080/07481180500298826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick TR, Spiro A, Kressin NR, Greene E, Bosse R. Leisure activities, stress, and health among bereaved and non-bereaved elderly men: The normative aging study. Omega. 2001;43:217–245. [Google Scholar]

- Hansson RO, Stroebe MS. Old age and widowhood: Issues of personal control and independence. Amercian Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hooyman NR, Kramer BJ. Living through loss: Interventions across the lifespan. Columbia University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. Bereavement and support: Healing in a group environment. Taylor & Francis; Washington DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CS. Nutritional considerations for bereavement and coping with grief. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2002;6:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CD, Bakk L. Later-life transitions into widowhood. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2001;35:51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lee MA, Carr D. Does the context of spousal loss affect the physical functioning of older widowed persons? Research on Aging. 2007;29(5):457–487. [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA. Taylor-Francis/Hemisphere Press; Washington, DC: 1989. Older bereaved spouses: Research with practical applications. [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA. Living with grief at work, at school, at worship. Brunner/Mazel; Levittown, PA: 1999. Giving and receiving help during later life spousal bereavement; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lund D, Utz R, Caserta M, de Vries B. Humor, laughter & happiness in the daily lives of recently bereaved spouses. Omega: Journal of Death & Dying. 2008;58(2):87–105. doi: 10.2190/om.58.2.a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Caserta M, de Vries B, Wright S. Restoration during bereavement. Generations Review. 2004;14:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Caserta MS. Future directions in adult bereavement research. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 1998;36:287–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Caserta MS. Facing life alone: The loss of a significant other in later life. In: Doka K, editor. Living with grief: Loss in later life. Brunner/Mazell; Levittown, PA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Caserta MS, Dimond MF. Older Bereaved Spouses: Research with Practical Applications. Hemisphere; New York: 1989. Impact of spousal bereavement on the subjective well-being of older adults; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lund DA, Caserta MS, Dimond MF, Shaffer SK. Older bereaved spouses: Research with practical applications. Taylor-Francis/Hemisphere Press; Washington, DC: 1989. Competencies: Tasks of daily living and adjustments to spousal bereavement in later life; pp. 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Montpetit MA, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Rausch JR. Adaptive change in self-concept and well-being during conjugal loss in later life. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 2006;63(3):217–239. doi: 10.2190/86WW-652A-M314-4YLA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss MS, Moss SZ, Hansson RO. Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2001. Bereavement and old age; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Neal MB, Carder PC, Morgan DL. Use of public records to compare respondents and nonrespondents in a study of recent widows. Research on Aging. 1996;18:219–242. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke N. Psychological resilience and the well-being of widowed women. Ageing International. 2004:267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS. Resilience and adaptation to stress in later life: Empirical perspectives and conceptual implications. Ageing International. 2004;29(3):219–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL. The role of daily positive emotions during conjugal bereavement. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;59B:P168–P176. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienta AM, Franks MM. A closer look at health and widowhood: Do health behaviors change after the loss of a spouse? In: Carr D, Neese RM, Wortman CB, editors. Spousal bereavement in late life. Springer; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Powers LE, Wampold BE. Cognitive-behavioral factors in adjustment to adult bereavement. Death Studies. 1994;18:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, McDonald J, Arcury TA, Bell RA, Vitolins MZ. Nutritional self-management of elderly widows in rural communities. Gerontologist. 2000;40:86–96. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson VE. A dual process model of grief counseling: Findings from the changing lives of older couples (CLOC) study. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2007;48:311–329. doi: 10.1300/j083v48n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson VE, Balaswamy S. Coping with bereavement among elderly widowers. Omega. 2001;43:129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom CA, Whittington FJ. The effects of bereavement on eating behaviors and nutrient intakes in elderly widowed persons. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1993;48:S223–S229. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.s223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer JA, Moos RH. Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping and care. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2001. Bereavement experiences and personal growth; pp. 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Schone BS, Weinick RM. Health-related behaviors and the benefits of marriage for elderly persons. Gerontologist. 1998;38:618–627. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.5.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar DR, Schultz R, Shahar A, Wing R. The effect of widowhood on weight change, dietary intake, and eating behavior in the elderly population. Journal of Aging and Health. 2001;13:186–199. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, Schut H. Update on DPM. Omega; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies. 1999;23:197–224. doi: 10.1080/074811899201046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO. Handbook of bereavement: Theory, research, and intervention. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Stroebe W, Schut H. Bereavement research: Methodological issues and ethical concerns. Palliative Medicine. 2003;17:235–240. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm768rr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census . Current population survey, special populations branch, marital status of the population 55 years and over by age and sex. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Utz R. Economic and practical adjustments to late life spousal loss. In: Carr D, Neese RM, Wortman CB, editors. Spousal bereavement in late life. Springer; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Utz RL, Carr D, Nesse R, Wortman C. The effect of widowhood on older adults’ social participation: An evaluation of activity, disengagement, and continuity theories. The Gerontologist. 2002;42(4):522–533. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz RL, Reidy E, Carr D, Nesse R, Wortman CB. The daily consequences of widowhood: The role of gender and intergenerational transfers on subsequent housework performance. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:683–712. [Google Scholar]

- Wells YD, Kendig HL. Health and well-being of spouse caregivers and the widowed. The Gerontologist. 1997;37(5):666–674. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Evenson KR, Aragaki A, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Mouton CP, Loevinger BL. The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health behaviors, and health outcomes: The women’s health initiative. Health Psychology. 2003;22(5):1–10. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. The transition to widowhood and the social regulation of health: Consequences for health and health risk behavior. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2004;59B(6):S343–S349. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.6.s343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden JW. Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner. 3rd ed. Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Znoj H. Bereavement and posttraumatic growth. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 176–196. [Google Scholar]