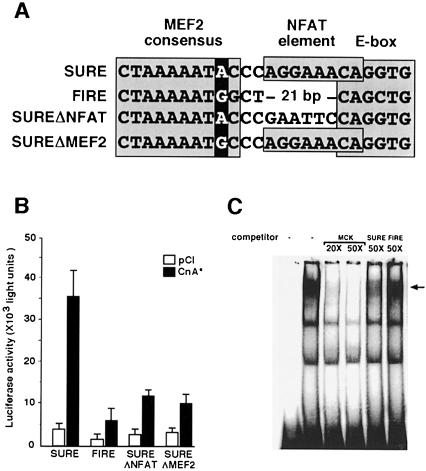

Fig. 5. MEF2 binding to slow and fast fiber-specific enhancers. (A) Nucleotide sequence alignment of segments of the rat TnI SURE and quail TnI FIRE enhancers (Nakayama et al., 1996) that include MEF2, NFAT and E box motifs. The putative MEF2 binding site in FIRE has a G nucleotide rather than an A nucleotide in position 9 of the MEF2 consensus binding motif (darkly shaded), and an NFAT consensus binding motif (boxed) found in SURE is not present in FIRE. The sequences of two variant forms of the SURE enhancer generated by site-directed mutagenesis are also illustrated. SUREΔNFAT and SUREΔMEF2 refer to variants in which NFAT and MEF2 binding motifs, respectively, are altered while leaving the remainder of the SURE enhancer sequence intact. The SUREΔMEF2 includes only the indicated single nucleotide substitution within an otherwise intact SURE enhancer. (B) Luciferase reporter constructs were prepared using the SURE or FIRE enhancers, or the indicated mutants thereof. Expression of luciferase following transfection of each of these reporter plasmids was assessed in the presence or absence of CnA*. Data are presented as in Figure 1 and represent mean values of two to four independent experiments. (C) EMSA of nuclear proteins from C2C12 cells using a high affinity MEF2 binding site (MCK-MEF2) as the labeled oligonucleotide probe. Unlabeled oligonucleotides (competitor) representing either the probe sequence (MCK-MEF2) or the MEF2 binding site from the SURE enhancer compete effectively with the labeled probe for binding MEF2, while the MEF2 motif from the FIRE enhancer competes less avidly. The identity of the MEF2–DNA complex (arrow) was confirmed by the change in mobility in the presence of anti-MEF2 antibodies (see Figure 2).

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official

government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock (

) or https:// means you've safely

connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.