Abstract

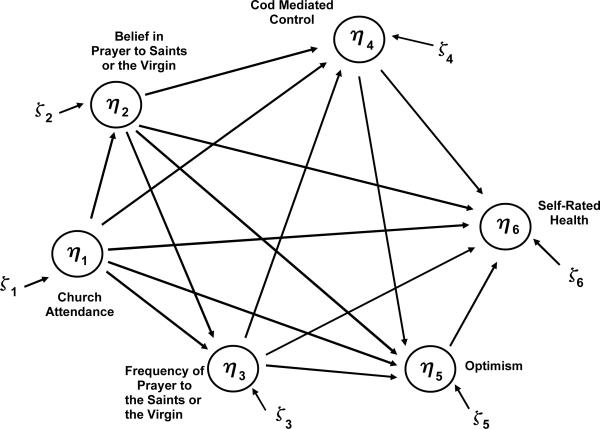

The purpose of this study was to evaluate a conceptual model that assesses whether praying to the saints or the Virgin is associated with the health of older Mexican Americans. A survey was conducted of 1,005 older Mexican Americans (Mean age = 73.9 years; SD = 6.6 years). Data from 795 of the Catholic respondents are presented in this study. The findings support the following relationships that are embedded in the conceptual model: (1) older Mexican Americans who attend church more often are more likely to believe in the efficacy of prayer to the saints or the Virgin; (2) stronger beliefs in the efficacy of intercessory prayer are associated with more frequent prayer to the saints or the Virgin; (3) frequent prayer is to the saints or the Virgin is associated with greater God-mediated control beliefs; (4) stronger God-mediated control beliefs are associated with greater optimism; and (5) greater optimism is associated with better self-rated health.

Keywords: prayer, health, older Mexican Americans

A rapidly growing body of research suggests that more frequent prayer is associated with better health (Lawler-Row & Elliott, 2009). It is not surprising to find that researchers are so interested in prayer because theologians have been arguing for centuries that prayer is one of the most important parts of a religious life. For example, John Calvin maintained that, “The necessity and utility of … (the) … exercise of prayer no words can sufficiently express” (1536/2006; p. 120). Similarly, Martin Luther argued that faith is, “… prayer and nothing but prayer…” (as reported by Heiler, 1932, xii). It is especially important for the purposes of the present study to note that Luther believed prayer could improve health. Quoting Ecclesiasticus, Luther claimed that, “The prayer of a good and godly Christian availeth more to health than the physician's physic” (Bell, 1650, p. 76).

Although research on prayer and health has provided many valuable insights, the purpose of the current study is to address three limitations in the work that has been done so far. First, most of the studies have been conducted with either whites or blacks (e.g., Krause & Chatters, 2005). This is unfortunate because the United States is rapidly becoming more racially diverse. The data from the current study come from a nationwide sample of older Mexican Americans. It is important to study members of this racial group because demographic projections indicate that the number of Hispanics age 65 and older will soon surpass the number of blacks age 65 and older to become the second largest ethnic group of older adults in the nation (Vincent & Velkoff, 2010).

Second, the wide majority of studies focus solely on how often an individual prays. This is true for older blacks and older whites (Levin, Taylor, & Chatters, 1994) as well as older Mexican Americans (Markides, 1983). Knowing how often someone prays is clearly an important aspect of prayer, but there is far more to it than this. For example, Poloma and Gallup (1991) found that some types of prayer (i.e., meditative prayer) exert a stronger influence on psychological well-being than other types of prayer (e.g., ritual prayer). Krause (2004a) provides evidence that the beliefs and expectations people have about prayers influence the relationship between prayer and well-being. More specifically, his data reveal that prayers are more likely to enhance well-being if individuals believe that it is important to wait for God to choose the proper time to respond to their requests.

An effort is made in the analyses that follow to contribute to the literature by examining a type of prayer that is practiced by Mexican Americans who affiliate with the Catholic Church - prayer that are offered to the saints and the Virgin of Guadalupe. The nature of prayers offered to the saints is discussed by Oktavec (1995). She observes that, “The saints are believed to …. (intercede) … with God to obtain special help for the faithful” (pp. 7– 8). Oktavec (1995) goes on to argue that Mexican Americans believe the saints are in an especially good position to perform this function because they are in heaven with God. Presumably, this close proximity to God coupled with the purity of their faith makes the saints especially powerful allies. A similar role has been ascribed to the Virgin of Guadalupe. Rodriguez (1994) maintains that in popular Mexican American religiosity, “God is rarely approached directly – hence the importance of powerful mediators such as … Mary” (p. 146). Moreover, as the participants in Rodriguez' (1994) study indicated, “God works through Mary/Our Lady of Guadalupe … Mary is accessible. And because we can approach her, we can approach God” (p. 122).

Unfortunately, prayers to the saints and the Virgin have been largely overlooked in the literature even though this type of prayer is quite common, as the data provided below will reveal. In fact, Ortiz and Davis (2008) observed recently that research on prayer to the saints and the Virgin is “… almost nonexistent …” (p. 29). And those few studies that examine this issue are either anecdotal in nature (e.g., Fernandez, 2007) or employ a qualitative research design (Rodriguez, 1994). Although these studies have contributed to the literature, quantitative research is needed so that the magnitude of the relationships can be assessed and the degree to which the study findings can be generalized can be determined.

The third limitation in the literature that is addressed in the current study has to do with the way researchers have analyzed data on the relationship between prayer and health. Most investigators have not conducted empirical analyses that are designed to explain how the potentially beneficial effects of pray arise. Instead, they merely report the direct effect of some aspect of prayer on health or well-being. A conceptual model is developed and empirically evaluated in the current study to explain how prayer to the saints and the Virgin affects health. This conceptual scheme is presented in the next section.

A Model of the Relationship Between Prayer and Health Among Older Mexican Americans

A theoretical model was evaluated for this study that contains the following core linkages: (1) It is proposed that older Mexican Americans who attend church more often will be more likely to believe that it is important to offer intercessory prayers to the saints or the Virgin; (2) older Mexican Americans who believe it is important to pray to the saints or the Virgin will offer prayers to these deities more often; (3) older Mexican Americans who pray to the saints or the Virgin more often will be more likely to believe that God helps them control the events they encounter in their lives (i.e., God-mediated control); (4) older Mexican Americans who have a stronger sense of God-mediated control will be more optimistic about the future; and (5) older Mexican Americans who feel more optimistic about the future will be more likely to rate their health in a favorable manner. The theoretical rationale for these relationships is provided below.

Church Attendance and Belief in Intercessory Prayer

Although attending worship services may benefit people in a number of ways, one of the most important functions has to do with instilling and reinforcing religious beliefs. These beliefs are transmitted through sermons, group prayers, hymns, and reading of sacred scriptures that typically take place during worship services. Evidence supporting this function is found in Stark and Finke's (2000) theory of religious involvement. Referring to religious beliefs as religious explanations, these investigators state that, “Confidence in religious explanations increases to the extent that people participate in religious rituals” (Stark & Finke, 2000, p. 107).

Prayer Beliefs and the Frequency of Prayer

Social psychologists have been arguing for decades about whether attitudes and beliefs predict behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 2005). As research in this field progressed, it quickly became evident that attitudes did not always predict behavior perfectly. Recently, Cohen, Shariff, and Hill (2008) observed that this problem also arises in the research on religion. More specifically, they note that there is often a large discrepancy between religious beliefs and religious behavior. However, Ajzen and Fishbein (2005) provide a resolution for the attitude-behavior discrepancy problem. They argue that there are two kinds of attitudes. The first are more general attitudes towards things like physical objects, racial groups, institutions, or world events. The second type has to do with predicting specific behaviors from specific attitudes. Ajzen and Fishbein (2005) argue that attitudes predict behavior quite well in the second more specific instance. Beliefs about intercessory prayer and the actual frequency of intercessory prayer may be construed as a specific belief and a specific behavior, respectively. So if the Ajzen and Fishbein (2005) are correct, the relationship between the two should be fairly strong.

The Frequency of Prayer and God-Mediated Control

Krause (2005) defines God-mediated control as the extent to which people believe it is possible to work together with God to resolve problems and attain goals in life. Recall that individuals pray to the saints or the Virgin because they believe these deities will intervene on their behalf with God. If this process works as it is supposed to and older Mexican Americans get what they have requested in their prayers, then they should feel that God has helped them gain control over some aspect of their lives. Simply put, older Mexican Americans who frequently offer prayers should have strong God-mediated control beliefs.

God-Mediated Control and Optimism

Optimism is defined as the expectation or confidence that outcomes that are desired for the future will ultimately be attained (Peterson, 2000). It is important to examine optimism or hope within the context of religion because, as Levin (2001) points out, “…every religion seeks to instill hope in those who subscribe to its teachings” (p. 138). Consequently, it is not surprising to find that a number of studies have found that various aspects of religion are associated with optimism and hope. For example, Sethi and Seligman (1993) found that people who feel religion has a strong influence on their daily lives are more likely to feel optimistic. Krause (2002a) reports that older whites and older blacks who feel they have a close relationship with God are more likely to feel optimistic. Moreover, a study by Macavei (2008) suggests that people who believe in a merciful and omnipotent God are more hopeful about the future. But there do not appear to be any studies that examine the relationship between feelings of God-mediated control and optimism. Even so, there is a sound reason why the two should be associated. If God is omnipotent and Mexican Americans believe He is working with them to control the things that arise in life, then it is not difficult to see why they would feel more optimistic about the future.

Optimism and Health

A fairly well-developed literature indicates that greater optimism is associated with better health (see Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010, for a review of this research). One of the most compelling studies of this issue was conducted by Peterson, Seligman, and Vaillant (1988). These investigators report that optimism is significantly associated with health over 35 year period. More specifically, this study revealed that people who are more optimistic tend to enjoy better health over time than individuals who are less optimistic.

There are four reasons why optimism and hope may have a salubrious effect on health. First, research indicates that people who are optimistic are more likely to take active steps to deal with the problems that confront them. In contrast, individuals who are pessimistic often fail to take needed action because they have little faith that their efforts will turn out as planned (Lazarus, 1999). Second, there is some evidence that individuals who are more optimistic are less likely to engage in health-damaging behaviors, such as smoking (Carver, Scheier, & Segerstrom, 2010). Third, people who are more optimistic are more likely to derive a deeper sense of meaning in life (Levin, 2001). This is important because a growing body of research indicates that a greater sense of meaning in life is associated with better health (Krause, 2004b) and a diminished risk of dying (Krause, 2009). Fourth, research indicates that hope and optimism are associated with a lower risk of developing mental health problems (Nunn, 1996) that may, in turn, influence physical health status (Cohen & Rodriguez, 1995).

Methods

Sample

The population for this study was defined as all Mexican Americans age 66 and over who were retired (i.e., not working for pay), not institutionalized, and who speak either English or Spanish. The sampling frame consisted of eligible study participants who resided in counties in the following five-state area: Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. The sampling strategy that was used for the widely-cited Hispanic Established Population for Epidemiological Study was adopted for the current study (see Markides, 2003, for a discussion of the steps that were followed). All interviews were conducted by Harris Interactive in 2009. The interviews were administered face-to-face in the homes of the older study participants. All interviewers were bilingual and study participants had the option of being interviewed in either English or Spanish. The wide majority of study participants (84%) preferred to be interviewed in Spanish. A total of 1,005 interviews were completed successfully. The response rate was 52%.

The analyses that are provided below were restricted to older Mexican Americans who affiliate with the Catholic faith. This is necessary because only members of this faith tradition pray to the saints or the Virgin. As a result, data provided by 795 older Mexican American Catholics are used in the analyses presented below.

The full information maximum likelihood estimation procedure (FIML) was used to deal with item non-response. As Graham, Olchowski, and Gilreath (2007) report, FIML provides results that are equivalent to the results provided by more time consuming procedures for dealing with item non-response, such as multiple imputation.

The average age of the participants was 73.9 years (SD = 6.6 years), approximately 45% were older men, 58% were married at the time the interview took place, and the average number of years of schooling that was completed by the study participants was 6.7 (SD = 3.8).

Measures

The core measures of religion for this study are provided in Table 1. All of the measures of religion, with the exception of church attendance, were developed for this study with an abbreviated version of the item development strategy outlined by Krause (2002b). More specifically, open-ended in-depth interviews were conducted with 52 older Mexican Americans who resided in South Texas (see Krause & Bastida, 2009). New closed-ended items to assess key dimensions of religion (e.g., intercessory prayer) were devised from these interviews. The items in the entire questionnaire were translated and back-translated from English into Spanish by a team of bilingual investigators. Following this, the quality of the newly devised closed-ended items was evaluated with 51 cognitive interviews that were conducted with a new sample of older Mexican Americans. This involved presenting study participants with the newly devised closed-ended items followed by a series of open-ended questions that were designed to see if they understood the questions in the intended manner. Finally, the closed-ended questions were again evaluated with 51 pretest interviews that were conducted with a new sample of participants.

Table 1.

Core Study Measures

|

This item is scored in the following manner (coding in parentheses): never (1), less than once a year (2), about once or twice a year (3), several times a year (4), about once a month (5), 2 to 3 times a month (6), nearly every week (7), every week (8), several times a week (9).

These items are scored in the following manner: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), agree (3), strongly agree (4).

This item is scored in the following manner: never (1), once in a while (2), fairly often (3), very often (4).

This item is scored in the following manner: poor (1), fair (2), good (3), excellent (4).

This item is scored in the following manner: worse (1), about the same (2), better (3).

This item is scored in the following manner: not at all satisfied (1), somewhat satisfied (2), very satisfied (3).

Church Attendance

The measure of church attendance reflects how often older study participants attended worship services in the year prior to the survey. A high score represents more frequent attendance. The mean level of church attendance is 5.0 (SD = 2.7).

Belief in Prayer

A single item was developed to determine whether older Mexican Americans believe that either the Virgin or the saints will intervene with God on their behalf if they ask them to do so in prayer. A higher score denotes greater belief in the efficacy of this type of intercessory prayer. Scores on this indicator range from 1 to 4. The mean is 3.3 (SD = 1.0), which suggests that belief in the efficacy of intercessory prayer is widespread among older Mexican Americans.

Frequency of Prayer

A single indicator was devised to determine how often study participants have actually prayed to the Virgin or the saints. A high score represents more frequent prayer. The mean is 3.3 (SD = .7).

God-Mediated Control Beliefs

As shown in Table 1, three items were administered to assess God-mediated control beliefs. A high score indicates that study participants are more likely to believe that God is helping them control the problems they have encountered and goals they aspire to attain in life. The mean of this brief composite is 10.6 (SD = 1.4).

Optimism

A sense of optimism was measured with three items. The first two come from the scale developed by Scheirer and Carver (1985). The third indicator was devised by Krause (2002a). The mean of the four items that assess optimism is 9.8 (SD = 1.5).

Self-Rated Health

Self-rated health was assessed with three widely-used indicators. A high score on these items reflects a more positive self-assessment of health. The mean of these three measures is 7.2 (SD = 1.7).

Results

Fit of the Model to the Data

Because the FIML procedure was used to deal with item non-response, the LISREL software program provides only two goodness-of-fit measures. The first is the full information maximum likelihood chi-square value (435.879; df = 66; p < .001). Unfortunately, this statistic is not informative because the sample for this study is large and as a result, the chi-square value is often highly significant. However, the second goodness-of-fit measure is more useful - the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The RMSEA value for the model is .084. As Kelloway (1998) reports, values below .10 indicate a good fit of the model to the data.

Reliability of Multiple Item Measures

Table 2 contains the factor loadings and measurement error terms that were derived from estimating the study model. These coefficients provide preliminary information about the reliability of the multiple item constructs. Kline (2005) maintains that items with standardized factor loadings in excess of .600 tend to have good reliability. As the data in Table 2 indicate, the standardized factor loadings range from .590 to .914. Only one coefficient was below .600, and the difference between this estimate (.590) and the recommended value of .600 is trivial.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings and Measurement Error Terms for Multiple Item Measures (N = 795)

| Construct | Factor Loadinga | Measurement Errorb |

|---|---|---|

| 1. God-Mediated Control | ||

| A. Rely on Godc | .590 | .652 |

| B. Succeed with God | .914 | .164 |

| C. All things are possible with God | .890 | .209 |

| 2. Optimism | ||

| A. Bright side | .853 | .273 |

| B. Optimistic about future | .843 | .290 |

| C. Expect the best | .678 | .540 |

| 3. Self-Rated Health | ||

| A. Rate overall health | .658 | .566 |

| B. Most people your age | .656 | .569 |

| C. Satisfied with health | .746 | .444 |

The factor loadings are from the completely standardized solution. The first-listed item for each latent construct was fixed to 1.0 in the unstandardized solution.

Measurement error terms are from the completely standardized solution. All factor loadings and measurement error terms are significant at the .001 level

Item content is paraphrased for the purpose of identification.

Although obtaining information about the reliability of each item is useful, it would also be helpful to know something about the reliability for the multiple item scales as a whole. Fortunately, it is possible to compute these estimates with a formula provided by DeShon (1998). This procedure utilizes the factor loadings and measurement error terms in Table 2. Applying the formula described by DeShon to these data yields the following reliability estimates for the multiple item constructs in the study model: God-mediated control (.848), optimism (.836), and self-rated health (.729). Taken as a whole, these reliability estimates are acceptable.

Substantive Findings

Estimates of the relationships among the latent constructs in the study model are provided in Table 3. Taken together, these findings provide support for each of the core hypotheses that were developed for this study. More specifically, the results reveal that older Mexican Americans who go to church more often are more likely to believe in the efficacy of prayer to the saints or the Virgin than older Mexican Americans who do not attend worship services as often (Beta = .147; p < .001). The data further indicate that older Mexican Americans who believe in the efficacy of prayer are likely to pray to the saints for the Virgin more often (Beta = .505; p < .001). Because the magnitude of this relationship is large by social and behavioral science standards, it appears that beliefs about the efficacy of prayer do indeed predict the behavior that is associated with these beliefs (i.e., the frequency of actual prayer). However, as the data in Table 3 further indicate, all the variables that are thought to determine the frequency of prayer explain 33.7% of the variance in this form of religious behavior. This suggests that even though attitudes about prayer predict the frequency of prayer, this type of religious behavior is also influenced by one or more constructs that are not contained in the study model.

Table 3.

Prayer to the Saints or the Virgin and Health (N = 795)

| Dependent Variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Church Attendance | Belief in Prayer | Frequency of Prayer | God-Mediated Control | Optimism | Health |

| Age | −.105**a (−.043)b | .094** (.010) | .079** (.012) | .139*** (.007) | −.046 (−.004) | .021 (.002) |

| Sex | −.175*** (−.953) | −.143*** (−.203) | −.114*** (−.227) | −.115** (−.080) | .053 (.054) | .036 (.040) |

| Education | .054 (.037) | −.018 (−.003) | .010 (.002) | .072 (.006) | .048 (.006) | .171*** (.024) |

| Marital status | .045 (.249) | .054 (.077) | .001 (.003) | .075* (.053) | −.014 (−.014) | .013 (.015) |

| Church attendance | .147*** (.038) | .126*** (.046) | .045 (.006) | .014 (.003) | .046 (.009) | |

| Belief in prayer | .505*** (.706) | .204*** (.099) | .333*** (.237) | −.086 (−.067) | ||

| Frequency of prayer | .132** (.046) | −.195*** (−.099) | .068 (.038) | |||

| God-mediating control | .412*** (.605) | −.027 (−.044) | ||||

| Optimism | .262*** (.286) | |||||

| Multiple R2 | .044 | .052 | .337 | .155 | .282 | .097 |

Standardized regression

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

The findings further suggest that older Mexican Americans who offer prayers to the saints and the Virgin more often are, in turn, more likely to believe that God is working with them to solve their problems and attain the goals they aspire to attain in life (Beta = .132; p < .01). The results indicate that older Mexican Americans who have a strong sense of God-mediated control are, in turn, more likely to feel optimistic than older Mexican Americans who do not have a strong sense of God-mediated control (Beta = 412; p < .001). Finally, having a strong sense of optimism is important because the data suggest that greater optimism is associated with more favorable self-rated health (Beta = .262; p < .001).

Three additional sets of findings that are presented in Table 3 have not been discussed up to this point. Even so, it is helpful to examine them briefly because so little empirical research has been done with prayer to the saints or the Virgin. First, the results suggest that believing in the efficacy of prayer is associated with stronger God-mediated control beliefs (Beta = .204; p < .001). It may appear at first glance that the relationship between belief in the efficacy of prayer and God-mediated control is stronger than the relationship between actually offering prayers and feelings of God-mediated control (Beta = .132; p < .01). Fortunately, a test can be performed to determine whether the difference in the magnitude of these estimates is statistically significant. This is accomplished by making an additional pass through the model after the two coefficients have been constrained to be equal. Then, the significance of the difference between the substantive estimates is determined by computing the change in the chi-square goodness-of-fit value from the analysis reported in Table 3 and the chi-square value that is obtained after the two coefficients were constrained to be equal. The results from this test reveal that the size of the two coefficients are not significantly different (chi-square change = 2.666; n.s.). Initially, this finding may be difficult to understand because there appears to be a fairly substantial difference in the magnitude of the standardized coefficients (i.e., .204 vs. .132). However, researchers have known for some time that tests of the difference in the size of regression coefficients should only be computed with unstandardized estimates (Hennessy, 1985). When the unstandardized effect of belief in the efficacy of intercessory prayer (b = .099) is compared with the unstandardized effect of the actual frequency of intercessory prayer (b = .046), the tests results become easier to grasp. Putting these technical issues aside, these additional analyses suggest that belief in the efficacy of prayer and the actual frequency of prayer play an equivalent role in shaping feelings of God-mediated control among older Mexican Americans.

The second set of additional findings involves the relationships among beliefs about the efficacy of prayer, the frequency of prayer, and optimism. The data in Table 3 indicate that stronger belief in the efficacy of prayer is associated with substantially stronger feelings of optimism (Beta = .333; p < .001). But in contrast, the frequency of actually offering prayers to the Virgin and the saints appears to be associated with a diminished sense of optimism (Beta = −.195; p < .001). Unfortunately, additional data were not available to pursue this unanticipated result further.

The third set of findings is more descriptive in nature. It is helpful to examine these findings given the lack of data on religion among older Mexican Americans. The data in Table 3 reveal that both age and sex are significantly associated with a number of the constructs in the study model. In particular, the results indicate that as Mexican Americans grow older, they tend to go to church less often (Beta = −.105; p < .001), they believe more strongly in the efficacy of prayer to the Virgin and the saints (Beta = .094; p < .01); they offer more prayers (Beta = .079; p < .01), and they have a stronger sense of God-mediated control. Moreover, the findings indicate that compared to older Mexican American women, older Mexican American men go to church less often (Beta = −.175; p < .001), believe less strongly in the efficacy of prayer (Beta = − .143; p < .001), offer fewer prayers (Beta = −.114; p <.001), and have a more diminished sense of God-mediated control (Beta = −.115; p <.001).

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to explore part of the deeply personal relationship that older Mexican Americans maintain with the saints and the Virgin through prayer. The intent was to show how this type of prayer arises and trace one way in which prayers to the saints and the Virgin may influence health. With respect to the first of these objectives, the data indicate that older Mexican Americans who go to church more often are more likely to believe in the efficacy of prayer to the saints and the Virgin. The findings further reveal that these beliefs, in turn, determine how often older Mexican Americans actually pray to the saints and the Virgin. With respect to the second objective, the results suggest that older Mexican Americans who pray to the saints and the Virgin more often are more likely to believe that God is helping them control the things that arise in life. The findings further indicate that older Mexican Americans with a strong sense of God-mediated control are more likely to feel optimistic, and a greater sense of optimism is, in turn, associated with better health.

There are three reasons why the findings from this study are noteworthy. First, this appears to be the first time that intercessory prayers by older Mexican Americans have been examined empirically. Second, unlike a number of previous studies, the data come from a representative nationwide sample of older Mexican Americans. Third, rather than merely seeing if prayer and health are related, an effort was made to evaluate two key intervening variables that link these important constructs (i.e., God-mediated control and optimism).

Although the findings from this study may have contributed to the literature, a considerable amount of research needs to be done. For example, researchers should make an effort to find out more about the nature of the specific requests that older Mexican Americans when they offer prayers to the saints or the Virgin. This would make it possible to see if prayers dealing with some issues (e.g., the health or well-being of significant others) have greater health-related effects than prayers that involve other matters (e.g., some sort of personal gain). In addition, research is needed on the outcomes of prayers to the saints or the Virgin. More specifically, studies should be conducted to see what happens when these prayers are not answered. One possibility is that unanswered prayers in highly valued areas may have a deleterious effect on health. Researchers also need to learn more about other pathways that may mediate the relationship between intercessory prayers and health. One potentially important pathway may involve feelings of gratitude. If older Mexican Americans offer prayers and their prayers are answered, then perhaps they feel more grateful to the saints or the Virgin and this sense of gratitude, in turn, enhances their health.

In the process of probing more deeply into the health-related effects of prayer to the saints and the Virgin, researchers should pay attention to the limitations in this study. Perhaps the most important shortcoming has to do with the cross-sectional nature of the data. Because the data for were gathered at a single point in time, the relationships among key study constructs were based on theoretical considerations alone. For example, it was proposed that older Mexican Americans who are optimistic have better health. However, one could just as easily argue that older Mexican Americans who have better health are more likely to be optimistic. Clearly this, as well as other causal assumptions that are embedded in the study model must be rigorously evaluated with studies that are based on a true experimental design.

Even though there are limitations in the work that has been done here, it is the hope of the authors that researchers will come to value the rich insights that can be obtained by studying the relationship between religion and health in racial groups that have been largely overlooked in the literature. As Hill and Hood (1999) report, research on religion has been dominated by samples of college students. By expanding the horizons of the literature beyond the college campus, research on older Mexican Americans holds out the promise of learning more about members of a racial group who are playing an increasingly more important role in our diverse society.

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model of Praying to the Saints

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG026259) and a grant from the John Templeton Foundation that was administered through the Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health at Duke University.

Author Biographical Sketches

Neal Krause, Ph.D., is the Marshall H. Becker Collegiate Professor in the Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, School of Public Health, at the University of Michigan. He received his doctoral training in the Akron University/Kent State University Joint Doctoral Program in Sociology. He is currently conducting two ongoing projects that focus on the relationship between religion and health among older whites, older African Americans, and older Mexican Americans. This work has been funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Elena Bastida, Ph.D., is Professor and Chair of the Department of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in the Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work at Florida International University. She received her doctoral degree from Kansas State University. Dr. Bastida is currently working on an intervention that is designed to reduce the risk of diabetes among Mexican Americans as well as an ongoing epidemiologic study of Mexican Americans who live in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas.

References

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In: Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Zanna MP, editors. The handbook of attitudes. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bell H. Selections from the table talk of Martin Luther. Kessinger; Breinigsville, PA: 1650. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin J. In: John Calvin: Steward of God's covenant. Thornton JF, Varene SB, editors. Random House; New York: 1536/2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AB, Shariff AF, Hill PC. The accessibility of religious beliefs. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:1408–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Rodriguez MS. Pathways linking affective disturbances and physical disorders. Health Psychology. 1995;14:374–380. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.5.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeShon RP. A cautionary note on measurement error correlations in structural equation models. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:412–423. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Eduardo C. Mexican-American Catholics. Paulist Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206, 213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiler F. Prayer: A study in the history and psychology of prayer. Oxford University Press; New York: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Hill PC, Hood RW. Measures of religiosity. Religious Education Press; Birmingham, AL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for structural equation modeling. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002a;57B:S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. A comprehensive strategy for developing closed-ended survey items for use in studies of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002b;57B:S263–S274. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.s263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Assessing the relationship among prayer expectancies, race, and self-esteem in late life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2004a;65:35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Stressors in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004b;59B:S287–S297. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging. 2005a;27:136–164. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Bastida E. Religion, suffering, and health among older Mexican Americans. Journal of Aging Studies. 2009;23:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Chatters LM. Exploring race differences in a multidimensional batter of prayer measures among older adults. Sociology of Religion. 2005;66:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler-Row KA, Elliott J. The role of religious activity and spirituality in the health and well-being of older adults. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14:43–52. doi: 10.1177/1359105308097944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. Hope: An emotional and vital coping resource against despair. Social Research. 1999;66:653–678. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS. God, faith, and health: Exploring the spirituality-healing connection. Wiley; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1994;49:S137–S145. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macavei B. An empirical investigation of the relationships between religious beliefs, irrational beliefs, and negative emotions. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies. 2008;8:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS. Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly 1993–1994. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2003. Study Number 2851. [Google Scholar]

- Matovina T. Beyond borders: Writings of Virgilio Elizondo and friends. Orbis Books; Maryknoll, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nunn KP. Personal hopefulness: A conceptual review of the relevance of the perceived future to psychiatry. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1996;69:227–245. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1996.tb01866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oktavec E. Answered prayers: Miracles and milagros along the border. University of Arizona Press; Tucson, AZ: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz FA, Davis KG. Latina/o folk saints and Marian devotions: Popular religiosity and healing. In: McNeill BW, editor. Latina/o healing practices: Mestizo and indigenous practices. Routledge/Taylor & Francis; New York: 2008. pp. 29–62. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. The future of optimism. American Psychologist. 2000;55:44–55. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Seligman ME, Vaillant GE. Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:23–27. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poloma MM, Gallup GH. Varieties of prayer: A survey report. Trinity Press International; Philadelphia: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J. Our Lady of Guadalupe. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Scheirer MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping and health: Assessment, and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi S, Seligman ME. Optimism and fundamentalism. Psychological Science. 1993;4:256–259. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Finke R. Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The next four decades: The older population of the United States: 2010 to 2050. U. S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]