Abstract

The authors report a case of an immunocompetent 38-year-old male who presented with an indolent keratitis that eluded diagnosis after multiple cultures taken over 9 months. He was started initially on medications against Acanthamoeba, after presenting with a nearly complete corneal ring 2 months after trauma. These medications likely partially treated his condition, thereby making laboratory diagnosis more difficult. He was identified as having Encephalitozoon hellum by PCR. The patient subsequently underwent cornea transplant after a full course of medical treatment and recovered best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20.

Background

We believe this is the first case of Encephalitozoon hellum keratitis in a healthy patient, and the association of a Wessely ring with microsporidial keratitis has not been previously reported.1 Treatment of keratitis against Acanthamoeba and Microsporidium overlap, which may be the reason that this patient initially responded to treatment against a presumed Acanthamoeba infection.

Case presentation

The patient's symptoms began in April 2009 after scratching his left eye with a towel. He was initially evaluated for upper respiratory complaints, left eye pain and discharge. His initial vision was 20/20 in the left eye; but over several weeks, he developed worsening symptoms.

The patient travelled frequently during this time and returned 2 months later with a 290 ° ring infiltrate. Suspicion for Acanthamoeba was high. He was referred to a local cornea specialist who sent Acanthamoeba and mycology cultures, which were negative. Confocal microscopy showed a possible trophozoite. The patient was started on chlorhexidine, polymyxin B/trimethoprim sulphate, neomycin/polymyxin B/gramicidin, atropine, fluconazole and naproxen. The patient's vision deteriorated acutely after treatment from 20/40 to 20/400, and he developed left-sided facial pain. Perineuritis was seen at 2:00 in the patient's left cornea. The patient was started a few days later on polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) and desomedine. Two herpes cultures were negative.

A ProKera graft (Bio-Tissue, Miami, Florida, USA) was placed in early August for a non-healing epithelial defect. Medications for Acanthamoeba were stopped. The graft was removed 2 weeks later, and a persistent 4.5 mm defect remained. Deep stromal vessels were noted at this time in the left cornea. The vision did not improve.

Investigations

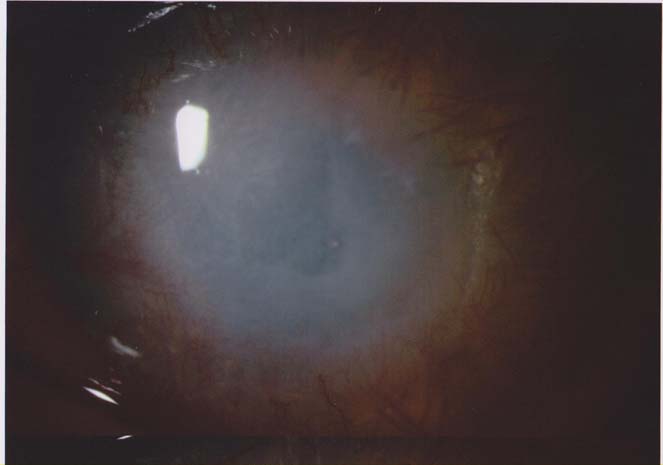

ENT was consulted in late June with concerns for a possibleAcanthamoeba sinusitis, but a sinus CT was negative. The patient was then referred to Shiley Eye Center and photos were taken (see figure 1). A trial of acyclovir despite two negative herpes cultures helped briefly, but his vision declined after initiating steroid eye drops. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures were negative.

Figure 1.

Patient presents with persistent epithelial defect, stromal haze and heavily vascularised cornea (left eye).

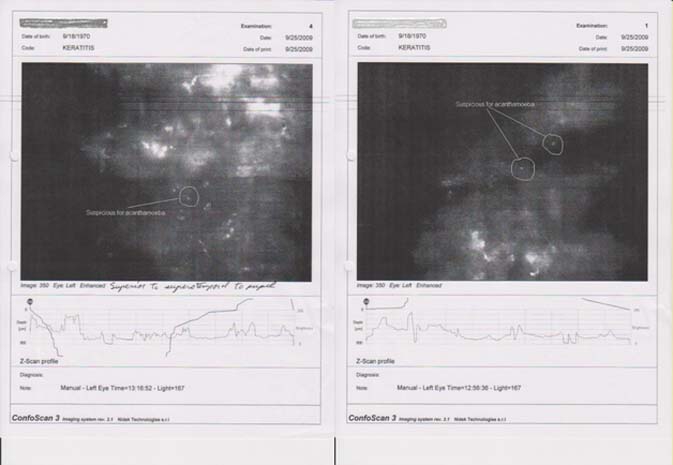

The patient was referred to a local confocal specialist who visualised two possible cysts or trophozoites on confocal imaging (see figure 2). However, the report was not definitive.

Figure 2.

Confocal images. Note the areas of concern deep in the stroma.

A corneal sample was sent for PCR testing against Acanthamoeba, herpes simplex virus (HSV) and herpes zoster virus (HZV), which were all negative.

The patient subsequently underwent a corneal biopsy 2 weeks later. PCR testing for Acanthamoeba (research-based), HSV and HZV were all again negative. A second section of the corneal biopsy sample was sent to pathology, where a single H&E section revealed clusters of minute basophilic bodies of similar size and shape, which deflected the pattern of the corneal lamellae. The possible diagnosis of microsporidial keratitis was raised.

All pathology slides were sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for analysis. PCR (research-based) testing using a concentrated sample confirmed E hellum.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a keratitis producing a corneal ring includes infection from Acanthamoeba, Gram-negative organisms and herpes,2 as well as proparacaine abuse. In this case, confocal results, perineuritis and a Wessely ring marked the initial diagnosis of Acanthamoeba. Few case reports of fungal organisms causing corneal rings exist.2 3

Treatment

The patient was started on topical fumagillin and oral albendazole. After 3 weeks of initial therapy, he underwent successful corneal transplant in January 2010. The patient's cornea sample was sent to the CDC, where PCR and cultures were negative for Microsporidium. Therapy was continued for 3 weeks postoperatively.

Outcome and follow-up

There has been no recurrence in the graft after 10 months, and his vision with contact lens remains 20/20.

Discussion

Reports of microsporidial keratitis are not uncommon, but none report the association of a corneal ring. Microsporidium infection can be diagnosed by routine histological staining; but providers should alert the microbiologist if suspicion exists to perform specialised staining, which was not initially done in this case. Common laboratory tests for Microsporidium include Gram stain (variable staining), Giemsa stain, Calcofluor white preparation, modified trichrome stain, 1% acid fast and Gram's chromotrope stain. Routine histologic stains include H&E and periodic acid-Schiff's.4 5 Definitive diagnosis includes electron microscopy,6 but most centres have limited access to such technology. More recently, diagnosis of microsporidial keratitis has been made utilising PCR techniques.7

Treatment regimens for microsporidial keratitis have been described in the literature and typically involve topical fumagillin and oral albendazole initially. Definitive therapy for stromal disease typically involves penetrating keratoplasty, and medical treatment should continue after surgery.6 8 9 Some authors have described the use of itraconazole and debulking of the cornea to reduce spore load.10 11 Other therapies that have been attempted include Neosporin,11 Brolene,12 PHMB, chlorhexidine10 and fluoroquinolones,13 overlapping with treatment for Acanthamoeba keratitis.14 Low-dose topical steroids are used by some surgeons postgraft,8 but use remains controversial.7 9 15

Learning points.

-

▶

Worsening pain, a partial corneal ring and perineuritis in a culture-negative setting would normally lead to a presumed diagnosis of Acanthamoeba.

-

▶

The presentation of a partial corneal ring in this case is unusual and has not been previously reported with Microsporidium infection of the cornea.

-

▶

Microsporidium infection is difficult to detect, particularly in our patient, and we believe that the patient was partially treated with medications againstAcanthamoeba.

-

▶

These infections are becoming more common; and diagnosis will improve as surgeons remember to think about Microsporidium infection in culture-negative cases of keratitis, even in healthy patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Visvesvara and Dr Folberg for their assistance in this case.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Wessely K. Ueber anaphylaktische Erscheinungen an der Hornhaut. Munchen MedWchnschr 1911;58:1713 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg P, Rao GN. Corneal ulcer: diagnosis and management. Community Eye Health 1999;12:21–3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salierno AL, Goldstein MH, Driebe WT. Fungal ring infiltrates in disposable contact lens wearers. CLAO J 2001;27:166–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia LS. Laboratory identification of the microsporidia. J Clin Microbiol 2002;40:1892–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joseph J, Vemuganti GK, Garg P, et al. Histopathological evaluation of ocular microsporidiosis by different stains. BMC Clin Pathol 2006;6:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Font RL, Samaha AN, Keener MJ, et al. Corneal microsporidiosis. Report of case, including electron microscopic observations. Ophthalmology 2000;107:1769–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conners MS, Gibler TS, Van Gelder RN. Diagnosis of microsporidia keratitis by polymerase chain reaction. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:283–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vemuganti GK, Garg P, Sharma S, et al. Is microsporidial keratitis an emerging cause of stromal keratitis? A case series study. BMC Ophthalmol 2005;5:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pariyakanok L, Jongwutiwes S. Keratitis caused by Trachipleistophora anthropopthera. J Infect 2005;51:325–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph J, Sridhar MS, Murthy S, et al. Clinical and microbiological profile of microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis in southern India. Ophthalmology 2006;113:531–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yee RW, Tio FO, Martinez JA, et al. Resolution of microsporidial epithelial keratopathy in a patient with AIDS. Ophthalmology 1991;98:196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metcalfe TW, Doran RM, Rowlands PL, et al. Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis in a patient with AIDS. Br J Ophthalmol 1992;76:177–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theng J, Chan C, Ling ML, et al. Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis in a healthy contact lens wearer without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Ophthalmology 2001;108:976–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun X, Zhang Y, Li R, et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: clinical characteristics and management. Ophthalmology 2006;113:412–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan CM, Theng JT, Li L, et al. Microsporidial keratoconjunctivitis in healthy individuals: a case series. Ophthalmology 2003;110:1420–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]