Abstract

In vivo mutation assays based on the Pig-a null phenotype, that is, the absence of cell surface glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored proteins such as CD59, have been described. This work has been accomplished with hematopoietic cells, most often rat peripheral blood erythrocytes (RBCs) and reticulocytes (RETs). The current report describes new sample processing procedures that dramatically increase the rate at which cells can be evaluated for GPI anchor deficiency. This new method was applied to blood specimens from vehicle, 1,3-propane sultone, melphalan, and N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea treated Sprague Dawley rats. Leukocyte- and platelet- depleted blood samples were incubated with anti-CD59-phycoerythrin (PE) and anti-CD61-PE, and then mixed with anti-PE paramagnetic particles and Counting Beads (i.e., fluorescent microspheres). An aliquot of each specimen was stained with SYTO 13 and flow cytometric analysis was performed to determine RET percentage, RET:Counting Bead ratio, and RBC:Counting Bead ratio. The major portion of these specimens were passed through ferromagnetic columns that were suspended in a magnetic field, thereby depleting each specimen of wild-type RBCs (and platelets) based on their association with anti-PE paramagnetic particles. The eluates were concentrated via centrifugation and the resulting suspensions were stained with SYTO 13 and analyzed on the flow cytometer to determine mutant phenotype RET:Counting Bead and mutant phenotype RBC:Counting Bead ratios. The ratios obtained from pre- and post-column analyses were used to derive mutant phenotype RET and mutant phenotype RBC frequencies. Results from vehicle control and genotoxicant-treated rats are presented that indicate the scoring system is capable of returning reliable mutant phenotype cell frequencies. Using this wild-type cell depletion strategy, it was possible to interrogate ≥ 3 million RETs and ≥ 100 million RBCs per rat in approximately 7 minutes. Beyond considerably enhancing the throughput capacity of the analytical platform, these blood-processing procedures were also shown to enhance the precision of the measurements.

Key terms: Pig-a gene, mutation, erythrocytes, GPI anchor, flow cytometry, CD59

1. Introduction

The Pig-a gene product is essential for the synthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors [1,2]. Hematopoietic cells require GPI anchors to attach a host of proteins to their cell surface, for instance CD59, CD24, CD55, CD48, among others [3]. Of the genes required to form GPI anchors, only Pig-a is located on the X-chromosome. Thus, one mutation to the Pig-a gene is capable of abolishing GPI anchor expression and therefore deposition of GPI-associated proteins at the cell surface. Enumeration of cells lacking GPI anchored proteins is highly amenable to flow cytometric analysis, and this analytical platform has been used by this and other laboratories to study chemicals’ in vivo mutagenic potential across several pre-clinical animal models [4–10].

The particular blood processing strategy that our group and several others involved in an inter-laboratory ring trial have utilized for proof-of-principle studies involves a platelet/leukodepletion-depletion step, anti-CD59-PE labeling, and finally SYTO® 13 staining [6,9–12]. This provides a means for studying mutation frequency in both the total erythrocyte (RBC) population, as well as the recently formed fraction of erythrocytes, the reticulocyte (RET) subpopulation. This methodology, as well as others that have been described to date, utilizes flow cytometric analysis to quantify the incidence of rare mutant phenotype cells through the interrogation of up to approximately 106 total cells. The spontaneous frequency of rodent erythrocytes with a null GPI anchor phenotype is very low, likely on the order of 10−6 [9,10,13]. It would therefore be ideal to evaluate several million or more RBCs and similarly large numbers of RETs in order to avoid zero readings and establish more accurate baseline measurements. Unfortunately, interrogating this many cells per sample is a time consuming process, especially for RETs, and analyses to date have therefore been based on suboptimal numbers of acquired cells. For instance, up until recently, practical considerations surrounding specimen throughput drove our decision to stop data acquisition when approximately 106 total RBCs and 0.3 × 106 total RETs per rat had been interrogated, a practice that typically required 20 minutes per blood specimen to achieve. Using this approach, of 203 Wistar Han rats evaluated [9,10], 82 mutant phenotype RBC readings and 93 mutant phenotype RET measurements resulted in zero values.

While mutant cell frequencies are often quite low, they are not zero. Clearly then, it would be advantageous to achieve higher rates of data acquisition in order to make it practical to interrogate many times more RBCs and RETs for GPI anchor deficiency. Such a method would be expected to have a greater ability to detect small increases in mutant cell frequency, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the endpoint. The subject of this current report is our solution to this technical challenge, a method we characterize as a wild-type cell depletion strategy.

The premise behind the new scoring procedure is that it is a simple matter to establish the denominator, that is, to enumerate total RBCs or even RETs. The problem with conventional approaches is that the vast majority of the data acquisition time is invested in counting wild-type cells, time that would be better used to observe and enumerate larger numbers of rare mutant phenotype cells. Therefore, one way to dramatically increase scoring rates and determine baseline frequencies with more confidence is to reverse this relationship such that the majority of data acquisition time is directed towards enumerating more mutant phenotype cells, not total cells. The method we devised to accomplish this involves the use of a commercially available immunomagnetic separation platform. As described previously [6,9,10], anti-CD59-PE is used to differentially label mutant and wild-type erythrocytes. In the new high throughput scoring method, anti-PE paramagnetic particles are added in order to specifically deplete samples of wild-type RBCs, resulting in mutant-enriched samples that are concentrated via centrifugation. Flow cytometric analysis of these samples enumerates many more mutant cells per unit time than has been previously possible. Even so, it is important to realize that the denominator, total cells, cannot be directly determined from these post-magnetic column specimens. The solution we developed involves the use of tracer fluorescent latex microspheres, referred to as Counting Beads in this report, that elute from the column along with mutant phenotype cells. As described in detail herein, by determining pre-column total cells to Counting Bead ratios and post-column mutant phenotype cells to Counting Bead ratios, one can readily calculate mutant cell frequencies.

This methodology is demonstrated for blood samples derived from vehicle-, 1,3-propane sultone-, melphalan-, and N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-treated Sprague Dawley rats. Beyond reporting the induced mutant cell frequencies observed, the results are discussed in terms of the increased throughput capacity and precision of the newly devised method as compared to previously described Pig-a scoring techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents

N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU; CAS no. 759-73-9), melphalan (MEL; CAS no. 148-82-3), 1,3-propane sultone (PS; CAS no. 1120-71-4), and sesame oil were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS; phenol red and divalent cation free) was from Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA. Lympholyte®-Mammal cell separation reagent was purchased from CedarLane, Burlington, NC (CAT no. CL5110). Anticoagulant Solution, Buffered Salt Solution, Nucleic Acid Dye Solution (contains SYTO® 13), and Stock Anti-CD59-PE were from Prototype In Vivo MutaFlow® kits (v091120, Litron Laboratories, Rochester, NY). Anti-CD61-PE was obtained from BD Biosciences. Anti-PE MicroBeads, LS Columns, and MidiMACS™ and QuadroMACS™ Separators were all from Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany. CountBright™ Absolute Count Beads and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA.

2.2 Animals, Treatments, Blood Collection

Experiments were conducted with the oversight of the University of Rochester’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA. Rodents were allowed to acclimate for approximately one week before treatment. Water and food were available ad libitum throughout the acclimation and experimental periods. Treatments were via oral gavage in a volume of 10 ml/kg body weight. ENU was prepared in PBS (pH 6.0), PS was prepared in deionized H2O, and MEL was prepared in sesame oil. Test articles were administered for either three or fourteen consecutive days at intervals of approximately 24 hr.

Initial experiments were conducted with blood specimens from MEL, ENU, and PS dose-range finding studies. Rats were treated for three consecutive days with a range of MEL or ENU doses, or for fourteen consecutive days with a range of PS doses. Blood samples were collected 15, 35, and 16 days after the final treatment with MEL, ENU, and PS, respectively. Blood was obtained by nicking a lateral tail vein with a surgical blade after animals were warmed briefly under a heat lamp. Approximately 100 μL of blood were collected into heparinized capillary tubes (Fisher Scientific, CAT no. 22-260-950). Immediately upon collection, 80 μL of each specimen were transferred to tubes containing 100 μL Anticoagulant Solution where they remained at room temperature for less than 2 hr, after which they were either immediately leukodepleted as described below, or stored at 4°C until leukodepletion (within 2 hrs).

A reconstruction experiment, described in detail below, was performed with blood from one vehicle control and one PS-treated rat. These animals were from the dose-range finding study described above (the PS-treated rat was treated with 30 mg/kg/day). For this experiment, approximately 5 mL cardiac puncture blood were collected from each animal into Anticoagulant Solution-coated needle and syringes 38 days after the final administration. Blood samples were maintained at room temperature for less than 2 hrs at which time they were leukodepleted as described below.

A time-course study was performed whereby three rats per group were treated on three consecutive days with 0, 4, 20, or 40 mg ENU/kg/day. Serial blood specimens were collected from each animal on day 1 (i.e., immediately before first administration) and again on days 7, 14 and 28. As described for the dose-range finding studies, above, blood was collected from the tail vein and 80 μL were combined with 100 μL Anticoagulant Solution. Leukodepletion occurred within 2 hrs as described below.

2.3 Cell Labeling: Basic Protocol

Previously described Pig-a cell processing and data acquisition procedures are collectively referred to herein as the “Basic Protocol” [9–10]. Briefly, 30 μL whole blood in 100 μL Anticoagulant Solution were platelet/leukocyte-depleted with Lympholyte. The resulting erythrocyte-enriched samples were incubated with saturating anti-CD59-PE, washed, and then resuspended in a balanced salt solution containing the nucleic acid dye SYTO 13. After incubating for 30 min at 37°C, flow cytometric analysis occurred within approximately 3 hrs.

2.4 Cell Labeling: High Throughput Protocol

The newly devised Pig-a cell processing and data acquisition procedures are collectively referred to as the “High Throughput Protocol” (for an overview see Figure 1). For this method, each 80 μL blood sample was combined with 100 μL Anticoagulant Solution and then platelet/leukocyte-depleted via centrifugation through 3 mL Lympholyte (30 minutes at 800 × g). Supernatants were removed and the erythrocyte-enriched pellets were rinsed through the addition and aspiration of 300 μL Buffered Salt Solution (two times). 150 μL of Buffered Salt Solution were added to each tube, cells were resuspended with pipetting, and 160 μL from each tube were transferred to new 15 mL polypropylene tubes containing 100 μL working anti-CD59-PE solution (300 μL Stock Anti-CD59-PE and 50 μL Stock Anti-CD61-PE per 650 μL Buffered Salt Solution + 2% FBS). After incubating for 30 min at 4°C, cell suspensions were transferred to tubes containing 10 mL Buffered Salt Solution + 2% FBS. Following centrifugation for 5 minutes at 340 × g, supernatants were aspirated and 100 μL Working Magnetic MicroBead Suspension were added (250 μL Stock Anti-PE MicroBeads per 650 μL Buffered Salt Solution + 2% FBS). Cells and magnetic particles were mixed and incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes. Pellets were tapped loose, 10 mL Buffered Salt Solution + 2% FBS were added to each tube, and the samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 340 × g. Working Counting Bead Solution, 1 mL/tube, was added (600 μL CountBright Absolute Count Beads per 9.4 mL Buffered Salt Solution + 2% FBS). Samples were resuspended and 20 μL of each were added to tubes containing 500 μL Working Nucleic Acid Dye Solution (325 μL Stock Nucleic Acid Dye Solution to 10 mL Buffered Salt Solution). These “Pre-Column” samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 mins and protected from light until flow cytometric analysis occurred as described below (within approximately 2 hrs).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the High Throughput Protocol. Platelet/leukocyte-depleted blood samples are first incubated with anti-CD59-PE in order to differentially label wild-type erythrocytes and mutant phenotype erythrocytes (PE-positive and PE-negative, respectively). Samples are then combined with anti-PE magnetic particles and Counting Beads, and then a small portion of each is stained with a nucleic acid dye and analyzed via flow cytometry to determine Pre-Column cell to Counting Bead ratios, as well as percent reticulocytes. The majority of each sample is passed over a column suspended in a magnetic field. Whereas the wild-type cells are largely retained in the column, mutant phenotype cells and Counting Beads are recovered in the eluate. Post-Column eluates are concentrated via centrifugation, stained with a nucleic acid dye, and analyzed via flow cytometry to determine mutant phenotype cell to Counting Bead ratios. Mutant phenotype cell frequencies are then derived from Pre- and Post-Column analyses.

The remainder/majority of each sample was applied to a Miltenyi LS Column suspended in a magnetic field (i.e., using QuadroMACS or MidiMACS Separators). Once blood cells fully entered a column, 5 mL of Buffered Salt Solution + 2% FBS were added and the eluate was collected into a 15 mL polypropylene centrifuge tube. The specimens were centrifuged for 5 mins at 800 × g, supernatants were aspirated, the pellets were tapped loose, and 300 μL Working Nucleic Acid Dye Solution were added to each tube. These “Post-Column” samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 mins and were then protected from light until flow cytometric analysis occurred as described below (within approximately 2 hrs).

2.5 Instrument Calibration Standard

An Instrument Calibration Standard (ICS) was generated on each day data acquisition occurred. Preparation and use of these samples has been described previously [9–10]. Briefly, ICS consist of approximately 50% wild-type cells and 50% mutant-mimicking cells, the latter consisting of RBCs that were processed in parallel with experimental samples but that were not incubated with antibody(s). The resulting samples provided sufficient numbers of RBCs that exhibited a full range of PE and SYTO 13 fluorescence intensities that were useful for optimizing PMT voltages and fluorescence compensation settings. The position of the mutant mimics also provided a rational approach for defining the vertical demarcation line used to distinguish mutant phenotype cells from wild-type cells [9–10].

2.6 Data Acquisition: Basic Protocol

A FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) providing 488 nm excitation and running CellQuest™ Pro v5.2 software was used for data acquisition and analysis. The means of scoring RET, mutant phenotype RBC (RBCCD59−), and mutant phenotype RET (RETCD59−) frequencies according to the Basic Protocol have been described in detail elsewhere [9–10]. Pertinent to this report, it should be emphasized that the first two measurements were determined from an initial flow cytometric analysis that acquired 106 RBCs per specimen in approximately 4 minutes time. The third measurement, RETCD59− frequency, was determined from a second analysis that typically acquired 0.3 × 106 RETs per sample in approximately 15 minutes.

2.7 Data Acquisition: High Throughput Protocol

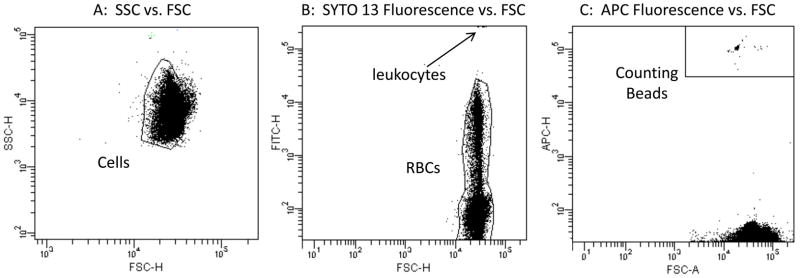

A FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) providing 488 nm and 633 nm excitation, running FACSDiva™ v6.1.1 software, was used for data acquisition and analysis. Stock filter sets were used, with Nucleic Acid Dye (SYTO 13) fluorescence evaluated in the FITC channel, Anti-CD59-PE fluorescence evaluated in the PE channel, and Counting Bead fluorescence evaluated in the APC channel. Gating logic is described by Figure 2. Stop modes were based on time. Specifically, for each Pre-Column specimen data acquisition occurred for 3 mins, while each Post-Column specimen timed out after 4 mins. Using the stock Medium fluidics rate setting, these timeframes provided enough acquired events to reproducibly determine RET, RETCD59−, and RBCCD59− frequencies as described below.

Figure 2.

Three bivariate graphs illustrate the gating logic used for the mutant scoring application described herein. In order for events to be considered an RBC and subject to evaluation of mutant phenotype versus wild-type phenotype status, they need to exhibit light scatter characteristics of cells (panel A), low/moderate SYTO 13-associated fluorescence consistent with erythrocytes and reticulocytes but not leukocytes (panel B), and low APC-associated fluorescence consistent with cells but not Counting Beads (panel C). Thus, while the Lympholyte reagent physically removes the bulk of platelets and leukocytes, and while Counting Beads are present in both Pre- and Post-Column specimens, this gating strategy ensures that mutant phenotype RET and RBC frequencies are not affected by these events.

2.8 Reconstruction Experiment

The analytical performance of the Basic and High Throughput Protocols was directly compared with a reconstruction experiment. For this study, blood from one PS treated rat and one age-matched vehicle control animal were collected, and the following ratios of whole blood were prepared: 0 to 1 (i.e., control blood only), 1 to 6, 1 to 2.5, and 1 to 0 (i.e., PS blood only). Since cell densities and %RET values were found to be similar across these specimens, relative mutant cell content could be calculated as follows: 0, 1/7, 1/3.5, and 1, expressed hereafter as 0%, 14.3%, 28.6%, and 100%. These four spiked samples were created before Lympholyte or other cell processing procedures were performed. Five technical replicates of each preparation were independently processed through the Basic and High Throughput Protocols. These replicates therefore provided a means to evaluate the reproducibility of the processing steps from the initial Lympholyte step through flow cytometric analysis. Based on the modest effect observed for this particular PS-treated animal, this experiment also provided an opportunity to consider the ability of each protocol to detect slight differences in mutant phenotype cell frequencies.

2.9 Calculations, Statistical Analyses

The incidence of RETs is expressed as frequency percent, whereas the incidence of mutant phenotype cells is expressed as number per 106. All %RET, mutant phenotype cell frequencies, averages, standard error, and correlation coefficient (r2) calculations were performed with Excel Office X for Mac® (Microsoft, Seattle, WA).

The data used to calculate RET mutant phenotype cell frequencies are derived from Pre- and Post-Column flow cytometric analyses, and representative bivariate plots are shown in Figure 3. The formulas used to calculate the RET and mutant phenotype cell frequencies are described below, where UL = number of events occurring in the upper left quadrant, UR = number of events occurring in the upper right quadrant, LL = number of events occurring in the lower left quadrant, LR = number of events occurring in the lower right quadrant, and Counting Beads = number of events occurring in the Counting Bead region.

Figure 3.

Bivariate plots of representative nucleic acid dye (SYTO 13) versus anti-CD59-PE fluorescence profiles. Note that only erythrocytes, that is gated events, are shown. Key to quadrants: Upper right = wild-type reticulocytes; Lower right = wild-type mature erythrocytes; Upper left = mutant phenotype reticulocytes; Lower left = mutant phenotype mature erythrocytes.

Plot A: Instrument calibration standard; mutant-mimicking cells (i.e., erythrocytes that were not incubated with anti-CD59-PE) were spiked into blood that was fully processed. This specimen provides enough events with a full range of fluorescence intensities to optimize PMT voltages and compensation settings on a daily basis. This calibration standard also provided a means for rationally and consistently setting the position of the vertical demarcation line that discriminates mutant phenotype erythrocytes from wild-type erythrocytes.

Plot B: Blood from an ENU-treated rat, Pre-Column analysis; this blood sample was obtained from a rat twenty-five days after the last of three administrations of 40 mg ENU/kg/day. While 106 total erythrocytes were acquired, and there is some indication of a mutant response (events in the UL and LR quadrants), Pre-Column analyses were only used to determine reticulocyte frequency, reticulocyte to Counting Bead ratio, and total erythrocyte to Counting Bead ratio.

Plot C: Blood from the same ENU-treated rat, Post-Column analysis; this sample was depleted of wild-type erythrocytes via immunomagnetic separation. With a subsequent centrifugation step, mutant phenotype cells become highly concentrated. The numbers of mutant phenotype reticulocytes and mutant phenotype erythrocytes are directly determined from this sample. Mutant phenotype cell frequencies require a denominator, that is, the total number of reticulcoytes and erythrocytes that were analyzed. These data were derived from the Pre-Column cell to bead ratios and the number of Counting Beads observed in the Post-Column sample. For this particular specimen, four minutes of Post-Column specimen data acquisition afforded the interrogation of 7.1 × 106 reticulocyte and 107.2 × 106 erythrocyte equivalents for the mutant phenotype.

Pre-Column Data

a = No. Pre-Column RETs = UL + UR

b = No. Pre-Column RBCs = UL + UR + LL + LR

c = No. Pre-Column Counting Beads = Counting Beads

Calculations Based on Pre-Column Data

d = Pre-Column RET to Counting Bead ratio = a/c

e = Pre-Column RBC to Counting Bead ratio = b/c

f = %RET = a/b * 100

Post-Column Data

g = No. Post-Column RETCD59− = UL

h = No. Post-Column RBCCD59− = UL + LL

i = No. Post-Column Counting Beads = Counting Beads

Calculations Based on Post-Column Data

j = Post-Column RETCD59− to Counting Bead ratio = g/i

k = Post-Column RBCCD59− to Counting Bead ratio = h/i

Calculations Based on Pre- and Post-Column Data

l = No. Post-Column RET Equivalents = d * i

m= No. Post-Column RBC Equivalents = e * i

n = No. RETCD59− per 106 Total RETs = g/l * 106

o = No. RBCCD59− per 106 Total RBCs = h/m * 106

Table I illustrates the use of these formulas with actual flow cytometric data. Specifically, this table provides raw numbers as well as calculated frequencies based on day 14 blood samples from the ENU time-course study, described above.

Table I.a.

Pre-Column Flow Cytometric Data, ENU Time-Course, Day 14 Samples.

| Rat ID | Treatment* | No. RETs (a) | No. RBCs (b) | No. Counting Beads (c) | RET:Bead Ratio (d) | RBC:Bead Ratio (e) | %RET (f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | Vehicle | 77,072 | 1,062,814 | 164 | 470.0 | 6,481 | 7.25 |

| V2 | Vehicle | 66,864 | 1,100,461 | 176 | 379.9 | 6,253 | 6.08 |

| V3 | Vehicle | 53,777 | 1,055,933 | 200 | 268.9 | 5,280 | 5.09 |

| E1 | Low ENU | 63,521 | 1,106,480 | 210 | 302.5 | 5,269 | 5.74 |

| E2 | Low ENU | 43,936 | 595,650 | 117 | 375.5 | 5,091 | 7.38 |

| E3 | Low ENU | 62,792 | 1,089,410 | 216 | 290.7 | 5,044 | 5.76 |

| E4 | Med. ENU | 59,318 | 1,023,721 | 211 | 281.1 | 4,852 | 5.79 |

| E5 | Med. ENU | 71,550 | 1,048,196 | 192 | 372.7 | 5,459 | 6.83 |

| E6 | Med. ENU | 65,397 | 1,109,955 | 181 | 361.3 | 6,132 | 5.89 |

| E7 | High ENU | 71,750 | 1,013,491 | 191 | 375.7 | 5,306 | 7.08 |

| E8 | High ENU | 72,893 | 1,044,410 | 210 | 347.1 | 4,973 | 6.98 |

| E9 | High ENU | 76,247 | 1,147,876 | 200 | 381.2 | 5,739 | 6.64 |

Low ENU = 4 mg/kg/day for 3 days, Med. ENU = 20 mg/kg/day for 3 days, High ENU = 40 mg/kg/day for 3 days. Calculations (a – f) are described in the text.

For the reconstruction experiment, Dunnett’s test was used to compare mean RETCD59− and RBCCD59− frequencies for each spiked sample against the no spike/baseline sample. Significant differences were indicated by p < 0.05 (JMP software for the Mac, v5, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Given the relatively small group sizes and the large induction of mutant phenotype cells observed in the ENU time-course study, a simple 3-fold increase in mean RETCD59− or RBCCD59− frequency over concurrent vehicle control was used to indicate a significant effect.

3. Results

3.1 Method Optimization

Initial experiments focused on re-optimization of the anti-CD59-PE antibody, since the High Throughput Protocol calls for more blood compared to the Basic Protocol (80 μL vs 30 μL). The new use of anti-CD61-PE, Anti-PE MicroBeads, and Counting Beads also required optimization. After these reagents were successfully titered and the use of Miltenyi LS Columns was found to adequately deplete samples of wild-type cells, we devised a two-step method for calculating the number mutant phenotype RETs and RBCs that is based on Pre- and Post-Column analyses (see Figure 3).

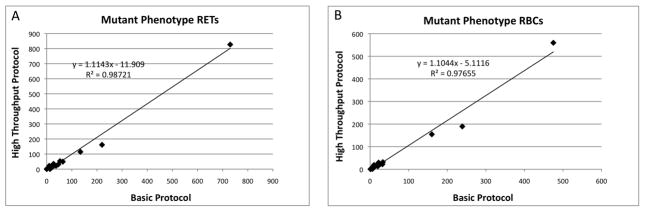

Having established a method for much more rapidly quantifying mutant phenotype cells, we began directly comparing results generated from the Basic Protocol with data derived from the High Throughput Protocol. As shown by Figure 4, these procedures generated mutant phenotype cell values that were highly correlated over a wide range of frequencies. These data lend strong support to an important assumption made in the High Throughput Protocol—whereas wild-type cells are largely retained by the columns, mutant phenotype cells and Counting Beads are reliably recovered in eluates. Note that analyses of column-trapped events added further direct support of this assumption. For example, using the optimized protocol, columns were found to consistently retain > 99% wild-type cells, whereas > 98% of the Counting Beads and mutant phenotype cells were observed in eluates.

Figure 4.

Mutant phenotype cell frequencies derived from the High Throughput Protocol (Y-axis) are graphed against parallel analyses conducted according to the Basic Protocol (X-axis). N = 18; Panel A = mutant phenotype reticulocyte frequencies; Panel B = mutant phenotype erythrocyte frequencies; best-fit lines and associated r2 values are shown. High correlation coefficients and similarities in absolute frequency values indicate that the two methods yield similar results over a broad range of mutant cell frequencies.

3.2 Reconstruction Experiment

Data from the reconstruction experiment are presented in Figure 5. As demonstrated by the best-fit lines, the Basic Protocol showed expected relationships between number of mutant phenotype cells scored and relative mutant content. Furthermore, the Basic Protocol resolved the two highest spiked samples (28.6% and 100%) from baseline when the RBCCD59− endpoint was considered (Dunnett’s test). On the other hand, only the 100% sample was identified as significantly different when the RETCD59− data were evaluated. The higher resolving power of the RBCCD59− endpoint was expected, since these measurements were based on 106 total RBCs per sample, whereas the RETCD59− endpoint was based on significantly fewer total RETs (0.3 × 106).

Figure 5.

Results from a reconstruction experiment are shown. Y-axis depicts the actual number of mutant phenotype cells scored, and the X-axis corresponds to the expected (relative) mutant cell content of each specimen, where 100 is the mutagen-treated animal (1,3-propane sultone), 0 is the vehicle control animal, and 14.3 and 28.9 correspond to 1:2.5 and 1:6 combinations of these blood samples, respectively. Each specimen was independently processed five times, and each individual measurement is plotted, and r2 values are shown. Panels A and B correspond to mutant phenotype erythrocyte and reticulocyte frequencies determined using the Basic Protocol, and Panels C and D correspond to analogous measurements made using the High Throughput Protocol. Samples that exhibited significantly different mutant phenotype cell frequencies relative to the control (0) specimen are indicted by asterisks (Dunnett’s test, p < 0.05).

Whereas the High Throughput Protocol generally produced similar absolute mutant phenotype cell frequencies compared to the Basic Protocol, the data were found to be considerably more reproducible, as evidenced by the higher r2 values (Figure 5). Unlike the Basic Protocol, the High Throughput Protocol was able to differentiate each spiked sample from baseline, and this was evident for both the RBCCD59− and RETCD59− endpoints. This ability to clearly resolve spiked samples from baseline was evident even for the 14.3% sample, where mean RBCCD59− and RETCD59− frequencies differed modestly from control (2.4-fold and 3.1-fold, respectively).

3.3 ENU Time-Course

Using the High Throughput Protocol, RET, RETCD59−, and RBCCD59− frequencies were determined following three days of treatment with several dose levels of ENU (see Figure 6). Consistent with previous observations [9–11], we observed marked age-related decreases in %RET. Day 7 %RET data are suggestive of a treatment-related reduction in the high dose group, although the small group sizes does not make it possible to comment definitively on this modest effect.

Figure 6.

Reticulocyte, mutant phenotype reticulocyte, and mutant phenotype erythrocyte frequencies following treatment with ENU are graphed. Panel A: average reticulocyte frequencies as a function of time relative to treatments that occurred on days 1, 2 and 3. Panel B: average mutant phenotype reticulocyte frequencies as a function of time. Panel C: average mutant phenotype erythrocyte frequencies as a function of time. All error bars are SEM. Note that Y-axis scales are different for mutant phenotype reticulocyte and mutant phenotype erythrocyte graphs. The higher responses observed in the reticulocyte subpopulation are expected over a 4 week experiment timeframe because the total erythrocyte pool has not completely turned over.)

The kinetics of ENU-induced RETCD59− and RBCCD59− induction have been reported previously [9,11], and the results reported herein are in close agreement. As expected, RETCD59− frequencies rose rapidly, with mean RETCD59− values for all three ENU treatment groups concurrent vehicle controls by more than 3-fold as early as day 7. By day 14, mean RETCD59− frequencies reached maximal values, with little change thereafter. Note that beyond exhibiting expected kinetics, the frequency of RETCD59− also closely agreed with previous reports [9,10].

The RBCCD59− endpoint is considered a lagging indicator of mutation relative to the RET cohort [4,9], and the data reported in Figure 6 are consistent with that expectation. Whereas the 20 and 40 mg ENU/kg/day treatment groups exhibited significantly increased mean RBCCD59− values by day 7, by day 14 and beyond all three ENU treatment groups clearly exceeded vehicle control frequencies. As with the RETCD59− endpoint, the frequency of ENU-induced RBCCD59− agreed with previous reports [9,11].

4. Discussion

Over the last several years the genetic toxicology community has expressed considerable enthusiasm for the in vivo Pig-a mutation endpoint [11–14]. Some of the most compelling factors that are driving interest in these assays are the following: i) there is no need to grow cells ex vivo to measure the frequency of mutant phenotype cells, ii) while mutation is a key event in carcinogenesis, most in vivo mutation assays have cost/technical limitations, iii) Pig-a-based methods provide a means of studying mode of action and dose-response relationships which are important for risk assessment, iv) unlike clastogenicity endpoints, Pig-a mutant cells accumulate with repeated dosing [7], v) cross-species potential is high [6,8,12], and vi) the endpoint integrates well with repeat-dosing experimental designs, for instance those commonly used in general toxicology studies [10].

Given these attractive attributes, this laboratory has coordinated an international multi-laboratory trial to systematically investigate the merits and limitations of Pig-a assays. Data generated using the Basic Protocol have been extremely promising, and suggest that assay portability is high [11; manuscript in preparation]. For each of the five potent genotoxicants that have been studied in the trial to date, the Basic Protocol is clearly capable of detecting treatment-related increases in mutant phenotype cell frequencies. However, significant in-house and inter-laboratory testing made it clear that spontaneous Pig-a mutant phenotype RET and RBC values are quite low, probably on the order of about 1 × 10−6 [9,10]. Even with the throughput capacity of modern flow cytometers, this rarity makes it challenging to interrogate enough cells to accurately define spontaneous mutant cell frequencies. This concern has been expressed by inter-laboratory trial collaborators, as well as two Pig-a working groups formed by HESI-IVGT. Each of these groups has suggested the need for a higher throughput scoring process, and the work described herein is our technical solution to this important advice and challenge.

Cell separation via paramagnetic particles is well known in the fields of cancer biology, hematology, and other disciplines that study rare cell types. Molecular biology techniques or flow cytometric analyses are often used to study the negatively or positively selected cells [15,16]. However, we are unaware of this separation technology being coupled with flow cytometry for the purpose of enumerating mutant phenotype RETs and RBCs. Of course, since the mutant phenotype cell-containing eluates are depleted of wild-type cells, it is not possible to directly measure the frequency of RETCD59− or RBCCD59−. Our solution was to use Counting Beads as tracer particles that move through the processing steps with mutant phenotype cells. With these tracers in place, it becomes possible to use Pre-Column total cell to Counting Bead ratios and Post-Column mutant phenotype cell to Counting Bead ratios to derive mutant cell frequencies.

This combination of immunomagnetic separation, Counting Beads, and flow cytometry results is an extremely high throughput method that is capable of interrogating on the order of ten times more RETs and one hundred times more RBCs per blood sample compared to the previous scoring technique, in about one-third the time it used to take. By acquiring many times more cells, the precision of the measurements is improved. This was exemplified by the spiking experiment described herein. Whereas samples that differed by as little as two- and three-fold over baseline could not be resolved using the Basic Protocol, they were clearly differentiated by the new method.

As promising as the data reported herein are, more work is needed before we can recommend broader adoption of the new scoring system. For instance, experiments at a number of collaborating laboratories are planned to test the portability of the High Throughput Protocol. Other work will be directed at better defining intra- and inter-animal variability, experiments that will benefit from the increased efficiencies of the new technique. These data, as well as the High Throughput Protocol itself, are predicted to benefit the international multi-laboratory trial, especially now that several groups are poised to expand their investigations from an initial set of five potent genotoxicants to a group of chemicals that includes weak mutagens as well as non-mutagens.

Table I.b.

Post-Column Flow Cytometric Data.

| Rat ID | Treatment | No. CD59- Neg. RETs (g) | No. CD59- Neg. RBCs (h) | No. Counting Beads (i) | CD59-Neg RET:Bead Ratio (j) | CD59-Neg RBC:Bead Ratio (k) | RET Equivalents (l) | RBC Equivalents (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | Vehicle | 4 | 28 | 16,718 | 2.39E−04 | 1.67E−03 | 7.86E+06 | 1.08E+08 |

| V2 | Vehicle | 2 | 76 | 16,624 | 1.20E−04 | 4.57E−03 | 6.32E+06 | 1.04E+08 |

| V3 | Vehicle | 2 | 33 | 17,650 | 1.13E−04 | 1.87E−03 | 4.75E+06 | 9.32E+07 |

| E1 | Low ENU | 131 | 756 | 17,878 | 7.33E−03 | 4.23E−02 | 5.41E+06 | 9.42E+07 |

| E2 | Low ENU | 253 | 950 | 18,056 | 1.40E−02 | 5.26E−02 | 6.78E+06 | 9.19E+07 |

| E3 | Low ENU | 130 | 775 | 18,750 | 6.93E−03 | 4.13E−02 | 5.45E+06 | 9.46E+07 |

| E4 | Med. ENU | 1,300 | 6,190 | 16,153 | 8.05E−02 | 3.83E−01 | 4.54E+06 | 7.84E+07 |

| E5 | Med. ENU | 1,891 | 8,610 | 17,366 | 1.09E−01 | 4.96E−01 | 6.47E+06 | 9.48E+07 |

| E6 | Med. ENU | 1,694 | 7,902 | 18,309 | 9.25E−02 | 4.32E−01 | 6.62E+06 | 1.12E+08 |

| E7 | High ENU | 3,614 | 15,242 | 17,517 | 2.06E−01 | 8.70E−01 | 6.58E+06 | 9.29E+07 |

| E8 | High ENU | 3,910 | 14,468 | 16,812 | 2.33E−01 | 8.61E−01 | 5.84E+06 | 8.36E+07 |

| E9 | High ENU | 4,346 | 18,905 | 18,676 | 2.33E−01 | 1.01E+00 | 7.12E+06 | 1.07E+08 |

Calculations (g – m) are described in the text.

Table I.c.

Frequencies Derived from Pre- and Post-Column Flow Cytometric Data.

| Rat ID | Treatment | CD59-Neg. RETs × 10−6 (n) | CD59-Neg. RBCs × 10−6 (o) |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | Vehicle | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| V2 | Vehicle | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| V3 | Vehicle | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| E1 | Low ENU | 24.2 | 8.0 |

| E2 | Low ENU | 37.3 | 10.3 |

| E3 | Low ENU | 23.9 | 8.2 |

| E4 | Med. ENU | 286.3 | 79.0 |

| E5 | Med. ENU | 292.2 | 90.8 |

| E6 | Med. ENU | 256.1 | 70.4 |

| E7 | High ENU | 549.2 | 164.0 |

| E8 | High ENU | 670.0 | 173.0 |

| E9 | High ENU | 610.4 | 176.4 |

Calculations (n – o) are described in the text.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the NIH-NIEHS to S.D.D. (R44ES018017). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS. The authors would like to thank Pamela Weller and Jared Mereness for expert technical assistance; Jeffrey Bemis, Ronald Fiedler, James MacGregor, Anthony Lynch, and Robert Heflich for many fruitful discussions; Inter-laboratory Pig-a Trial collaborators for their intellectual and benchtop contributions to this line of investigation; and the HESI IVGT Group for forming two Pig-a subgroups—their advice regarding adequate numbers of cells analyzed per rodent stimulated much of the work described herein.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors work for Litron Laboratories, a company that has filed patent applications related to mutant cell scoring based on the GPI anchor deficient phenotype.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Takahashi M, Takeda J, Hirose S, Hyman R, Inoue N, Miyata T, Ueda E, Kitani T, Medof ME, Kinoshita T. Deficient biosynthesis of N-acetylglucosaminyl-phosphatidylinositol, the first intermediate of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis, in cell lines established from patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. J Exp Med. 1993;177:517–512. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawagoe K, Takeda J, Endo Y, Kinoshita T. Molecular cloning of murine Pig-a, a gene for GPI-anchor biosynthesis, and demonstration of interspecies conservation of its structure, function, and genetic locus. Genomics. 1994;23:566–574. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez-Campo PM, Almeida J, Matarraz S, de Santiago M, Luz Sanchez M, Orfao A. Quantitative Analysis of the Expression of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Proteins During the Maturation of Different Hematopoietic Cell Compartments of Normal Bone Marrow. Cytometry. 2007;72B:34–42. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryce SM, Bemis JC, Dertinger SD. In Vivo Mutation Assay Based on the Endogenous Pig-a Locus. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008;49:256–264. doi: 10.1002/em.20379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miura D, Dobrovolsky V, Kasahara Y, Katsuura Y, Heflich R. Development of an In Vivo Gene Mutation Assay Using the Endogenous Pig-A Gene: I. Flow Cytometric Detection of CD59-negative Peripheral Red Blood Cells and CD48-negative Spleen T-cells from the Rat. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008;49:614–621. doi: 10.1002/em.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miura D, Dobrovolsky V, Mittelstaedt R, Kasahara Y, Katsuura Y, Heflich R. Development of an In Vivo Gene Mutation Assay Using the Endogenous Pig-A Gene: II. Selection of Pig-A mutant Rat Spleen T-cells with Proaerolysin and Sequencing Pig-A cDNA from the Mutants. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2008;49:622–630. doi: 10.1002/em.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phonethepswath S, Bryce SM, Bemis JC, Dertinger SD. Erythrocyte-based Pig-a gene mutation assay: Demonstration of cross-species potential. Mutat Res. 2008;657:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miura D, Dobrovolsky VN, Kimoto T, Kasahara Y, Heflich RH. Accumulation and persistence of Pig-A mutant peripheral blood cells following treatment of rats with single and split doses of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea. Mutat Res. 2009;677:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobrovolsky VN, Shaddock JG, Mittelstaedt RA, Manjanatha MG, Miura D, Uchikawa M, Mattison DR, Morris SM. Evaluation of Macac mulatta as a model for genotoxicity studies. Mutat Res. 2009;673:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phonethepswath S, Franklin D, Torous DK, Bryce SM, Bemis JC, Raja S, Avlasevich S, Weller P, Hyrien O, Palis J, MacGregor JT, Dertinger SD. Pig-a Mutation: Kinetics in rat erythrocytes following exposure to five prototypical mutagens. Tox Sci. 2010;114:59–70. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dertinger SD, Phonethepswath S, Franklin D, Weller P, Torous DK, Bryce SM, Avlasevich S, Bemis JC, Hyrien O, Palis J, MacGregor JT. Integration of mutation and chromosomal damage endpoints into 28-day repeat dose toxicology studies. Tox Sci. 2010;115:401–411. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dertinger SD, Phonethepswath S, Weller P, Stankowski LF, Jr, Roberts DJ, Shi J, Krsmanovic L, Vohr H-W, Custer L, Gleason C, Henwood A, Sweder K, Giddings A, Lynch AM, Gunther WC, Thiffeault CJ, Shutsky TJ, Fiedler RD, Bhalli JA, Heflich RH. Pig-a mutation assay: Evaluation of Inter-laboratory transferability and reproducibility. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:730. doi: 10.1002/em.20672. (Abstract P86) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobrovolsky VN, Miura D, Heflich RH, Dertinger SD. The in vivo Pig-a gene mutation assay, a potential tool for regulatory safety assessment. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:825–835. doi: 10.1002/em.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch AM, Sasaki JC, Elespuru R, Jacobson-Kram D, Thybaud V, De Boeck M, Aardema MJ, Aubrecht J, Benz RD, Dertinger SD, Douglas GR, White PA, Escobar PA, Fornace A, Jr, Honma M, Naven RT, Rusling JF, Schiestl RH, Walmsley RM, Yamamura E, van Benthem J, Kim JH. New and emerging technologies for genetic toxicity testing, Environ. Mol Mutagen. doi: 10.1002/em.20614. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thybaud V, MacGregor JT, Müller L, Crebelli R, Dearfield K, Douglas G, Farmer PB, Gocke E, Hayashi M, Lovell DP, Lutz WK, Marzin D, Moore M, Nohmi T, Phillips DH, Van Benthem J. Strategies in case of positive in vivo results in genotoxicity testing. Mutat Res. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.09.002. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belvedere O, Feruglio C, Malangone W, Bonora ML, Donini A, Dorotea L, Tonutti E, Rinaldi C, Pittino M, Baccarani M, Del Frate G, Biffoni F, Sala P, Hilbert DM, Degrassi A. Phenotypical characterization of immunomagnetically purified umbilical cord blood CD34+ cells. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 1999;25:140–145. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1999.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iinuma H, Okinaga K, Adachi M, Suda K, Sekine T, Sakagawa K, Baba Y, Tamura J, Kumagai H, Ida A. Detection of tumor cells in blood using CD45 magnetic cell separation followed by nested mutant allele-specific amplification of p53 and K-ras genes in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer (Pred Oncol) 2000;89:337–344. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000720)89:4<337::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]