Abstract

Rationale

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and protein kinase B (PKB or Akt) in the striatum are differentially activated by acute and repeated amphetamine (AMPH) administration. However, the dopamine receptor subtypes that mediate transient vs. prolonged phosphorylation changes in these proteins induced by AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats are unknown.

Objectives

The role of the D1 and D2 class of dopamine receptors in the differential phosphorylation of striatal ERK, CREB, Thr308-Akt and Ser473-Akt and the expression of behavioral sensitization induced by AMPH challenge in AMPH-pretreated rats was determined.

Methods

D1 or D2 dopamine receptor antagonists were injected before an AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. After behavioral activity was recorded, rats were euthanized either 15 min or 2 hr after AMPH challenge and striatal phosphoprotein status was analyzed by Western blotting.

Results

The D1 receptor antagonist (SCH23390) decreased stereotypical behavior whereas the D2 receptor antagonist (eticlopride) decreased all behavioral activity induced by an AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. SCH 23390, but not eticlopride, significantly decreased ERK, CREB, and Thr308-Akt phosphorylation in the striatum 15 min, and ERK and CREB phosphorylation 2 hr, after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. In contrast, eticlopride, but not SCH23390, prevented a decrease in Akt phosphorylation 2 h after AMPH challenge.

Conclusions

These data indicate that the time course of phosphoprotein signaling is differentially regulated by D1 and D2 receptors in the striatum of AMPH-sensitized rats, suggesting that complex regulatory interactions are activated by repeated AMPH exposure.

Keywords: Amphetamine, Sensitization, Striatum, CREB, Akt, ERK, Dopamine, Phosphorylation

INTRODUCTION

Repeated exposure to psychostimulants such as cocaine or amphetamine (AMPH) causes long-term cellular changes accompanied by specific behaviors that are believed to model the effects of repeated drug exposure in humans (Kalivas and Stewart 1991; Robinson and Berridge 1993; Nestler 2004; Wolf et al. 2004). By stimulating dopamine release in the striatum, AMPH alters phosphoprotein activation and gene transcription in postsynaptic neurons that contribute to these long-term changes in synaptic plasticity.

Cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) is a common phosphoprotein target of multiple kinase cascades activated by psychostimulants, such as protein kinase A (PKA), calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinases (CaMK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and protein kinase B/Akt, (Brami-Cherrier et al. 2002; Licata and Pierce 2003; Nestler 2004; Girault et al. 2007). Acute psychostimulant-induced ERK, Akt, and CREB phosphorylation is mediated, in part, by D1 receptors that stimulate PKA signaling in striatonigral (direct pathway) neurons (Brami-Cherrier et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2004; Valjent et al. 2005; Bertran-Gonzalez et al. 2008). However, D2 agonists can phosphorylate ERK and CREB via Gq-coupled phospholipase Cβ signaling (Yan et al. 1999; Brami-Cherrier et al. 2002).

G-protein-coupled receptors also regulate the activity of PKB/Akt at serine-473 (Ser473) and threonine-308 (Thr308) but the mechanisms and functional consequences are poorly understood. Although Thr308 phosphorylation activates Akt, phosphorylation of both residues provides greater catalytic activity (Alessi et al. 1996, Manning and Cantley 2007). However, unlike neurotrophin receptor stimulation, dopamine D1 or D2 receptor agonists phosphorylate Akt at the Thr308 residue, not via phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), but via PKA and ERK activation in primary striatal cultures (Brami-Cherrier et al. 2002). Further, acute D2 receptor antagonism only phosphorylated Thr308-Akt, whereas chronic D2 antagonism phosphorylated both Thr308 and Ser473, in the striatum of mice (Emamian et al. 2004). Conversely, acute AMPH exposure can lead to a delayed, protracted dephosphorylation of Akt at Thr308, but not at Ser473, in a D2 receptor-β-arrestin 2-protein phosphatase 2A (D2R/β-arrestin 2/PP2A)-dependent manner (Beaulieu et al. 2005). However, any changes in the phosphorylation of striatal Akt at Ser473 in relation to chronic AMPH exposure remain unexplored.

In a previous study, we demonstrated that 15 min after a low dose (1 mg/kg) AMPH challenge, there was a greater increase of striatal ERK1/2, CREB, and Thr308-Akt phosphorylation in the striatum of AMPH-sensitized rats than in saline-pretreated rats (Shi and McGinty 2007) similar to the augmented phosphorylation of CREB after repeated high dose (5 mg/kg) AMPH administration (Cole et al. 1995; Simpson et al. 1995). Furthermore, in our 2007 study, there was a sustained increase in phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2 and p-CREB 2 h after an AMPH challenge in AMPH- sensitized, but not in saline-pretreated, rats. In contrast, there was a decrease of p-Thr308-Akt 2 hr after the AMPH challenge in both AMPH-sensitized and in saline-pretreated, rats. However, the dopamine receptor subtypes that mediate the early and prolonged increase in phosphoproteins vs. the delayed decrease of p-Thr308-Akt induced by AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats were undetermined at that time.

The contribution of dopamine receptor subtypes to the development of behavioral sensitization in response to AMPH has been extensively studied by blocking D1 and D2 receptors during repeated AMPH administration. These studies support a critical role for D1 receptors and a supporting or secondary role for D2 receptors in the development of AMPH sensitization (reviewed in Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000). However, even though elevated dopamine transmission is also involved in the expression of AMPH sensitization in response to an AMPH challenge after at least one week of withdrawal (), there is no consensus about the role of D1 and D2 receptors in the expression of longterm behavioral sensitization (Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000). In fact, the effects of pharmaclogical blockade of D1 and D2 receptors immediately prior to an AMPH challenge injection have not been described, perhaps because these antagonists often suppress spontaneous motor activity at the doses commonly used (Ushijima et al, 1995). Therefore, in this study, AMPH-sensitized rats were treated with a selective D1 or D2 receptor antagonist prior to an AMPH challenge to determine the dopamine receptor subtype that mediates the early and late phosphoprotein responses to AMPH.

METHODS

Subjects

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–275 g, Charles River, Raleigh, NC, USA) were habituated to the home room for 1 week prior to any drug administration. Three days prior to each experiment, they were singly housed and handled to minimize any stress-induced behaviors. Food and water were provided ad libitum and rats were maintained on a 12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM). All animals were weighed on each day of the experiment. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to minimize the number of animals used in this study. All procedures used on the rats were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Four experiments were performed in order to determine whether different subtypes of striatal dopamine receptors mediate the differential regulation of striatal ERK, CREB, and Akt activation induced by AMPH in sensitized rats. All injections and behavioral ratings were performed in the homecages of rats. In each experiment, all rats were pretreated with saline or 5 mg/kg, i.p. AMPH once a day for 5 consecutive days. Their behavior was rated by observation on day 1 and day 5, using a 9-point scale described below (modified from Ellinwood and Balster, 1974). After a 14-day abstinence period, the intensity of AMPH-induced behavior in response to a challenge injection of AMPH (1 mg/kg, i.p.) was evaluated using the same rating scale. This AMPH sensitization paradigm was adapted from Wolf and Jeziorski (1993) and has been used previously in this laboratory (Wang and McGinty 1995a; Shi and McGinty 2007).

Doses of the antagonists were selected to minimize any effects on spontaneous activity that would confound interpretation of AMPH-induced behavioral activity. Antagonist doses were chosen based on a series of pilot studies performed using the AMPH senistization protocol. Doses of 0.01 mg/kg and 0.025 mg/kg of the D1 receptor antagonist, SCH23390, and 0.03 and 0.1 mg/kg of the D2/D3 antagonist, eticlopride, were injected i.p. prior to AMPH according to previous evidence that these doses blocked the locomotor stimulating effects of acute AMPH without altering spontaneous behavioral activity (Garrett and Holtzman, 1994). Our preliminary studies indicated that 0.01 and 0.025 mg/kg of SCH23390 did, and 0.03 mg/kg of eticlopride did not, affect AMPH-induced behavior and phospho-protein expression in sensitized rats (Online Resource 2–3, Fig. S2–3). Thus, 0.01 mg/kg of SCH23390 and 0.1 mg/kg of eticlopride were chos en to be injected in subsequent experiments prior to an AMPH challenge to examine the contribution of D1 and D2 receptors to the expression of behavior and to the differential phosphorylation of striatal ERK, CREB, and Akt at early and delayed timepoints in AMPH-sensitized rats. Pretreatment times were selected from previous experiments with these drugs (Wang and McGinty, 1995b).

In Experiments 1a and b, SCH 23390 (0.01 mg/kg, i.p.) was injected 15 min prior to a challenge injection of AMPH (1 mg/kg, i.p.). In Experiments 2a and b, eticlopride (0.1 mg/kg, i.p.) was injected 30 min before AMPH. In each experiment, the rats were randomly assigned to four different groups (n=4–6 per group): (1) saline (SAL) / SAL + SAL (indicating repeated administration followed 14 days later by saline or dopamine receptor antagonists and challenge), (2) SAL/antagonist + SAL, (3) AMPH /SAL + AMPH, (4) AMPH /antagonist + AMPH. The behavioral activity of the rats was rated by observation (see below) before they were anesthetized with Equithesin (10 mg/kg, i.p.) and decapitated 15 min (Experiment 1a and 2a) or 2 h (Experiment 1b and 2b) later.

Behavior

A behavioral rating scale was used in lieu of photocell activity cages in order to evaluate stereotypical behaviors in addition to locomotor activity (Kelley 2001) as described previously (Wang and McGinty 1995a; Shi and McGinty 2007). In experiments 1–2a, on days 1 and 5, the rats were observed and their behavior was rated 5 min before the saline or AMPH injection and every 10 min for 2 hr. On the challenge day, their behavior was rated 5 min before the first (antagonist or saline) injection and at 5 min intervals for 10 min after the second (saline or AMPH) injection. In experiments 1–2b, on days 1 and 5, the rats’ behavior was rated 5 min before the saline or AMPH injection and every 10 min for 2 hr. On the challenge day, the behavior of each rat was rated 10 min prior to the first injection and at 10 min intervals after the second injection for a period of 2h. In order to monitor locomotion as well as stereotypical behavior, a 9-point rating scale modified from Ellinwood and Balster (1974), was used in all experiments: (1) asleep, inactive; (2) normal activities, grooming; (3) increased activity; (4) hyperactive running with jerky movements; (5) slow patterned (repetitive exploration); (6) fast patterned (repetitive exploration with hyperactivity); (7) stereotypy (repetitive sniffing/rearing in one location to the exclusion of other activities; (8) continuous gnawing, sniffing or licking; (9) dyskinesia, seizures.

Western blotting

After the rats were anesthetized and decapitated, the brains were removed, placed ventral side up in a brain mold on wet ice, and a 2 mm slab was cut through the caudal aspect of the olfactory tubercle and 2mm anterior yielding a coronal slab (~+0.2 mm to +2.2 mm AP). The coronal slab was placed onto a glass plated cooled with wet ice, and the dorsal striatum was dissected freehand (cut horizontally above anterior commissure and along the ventral surface of the corpus callosum to lateral ventricles) and frozen in dry ice, stored at −8°C. Tissue from the dorsal striatum was thawed and sonicated in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) buffer and boiled for 5 min, then centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000g in an Eppendorf tabletop centrifuge, and the resulting supernatant was used as the soluble fraction. Protein concentrations were determined according to the Micro-BCA assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein (15 µg) were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (12% polyacrylamide), and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody diluted in 3% (p-ERK, ERK) or 5% (p-AktThr308, pAktSer473, p-CREB) milk/TBST buffer (Tris-buffered saline plus 0.1% Tween-20). The membranes were probed with rabbit primary antisera (Cell Signaling Technology) against p-ERK (1:500), p-CREB (1:1000), p-Thr308-Akt (1:3000), p-Ser473-Akt (1:1000) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then incubated with goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antiserum (1:1000-1:4000-Millipore). Finally, the blots were washed 3×10 min in TBST and developed for 1–5 min using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus) procedure of Amersham Biosciences. The signals were exposed on Hyperfilm (Amersham Biosciences), and then the same membranes were reprobed for proteins independently of their phosphorylation state after stripping in a mild buffer (Re-Blot Plus Western Blot Mild Antibody Stripping Solution, Millipore) and probed with antisera (1:1000) against ERK1/2, CREB, or Akt (Cell Signaling Technology), as quantitative loading controls. The integrated band density of each phosphoprotein and total protein sample was measured using Image J.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Behavioral data were analyzed by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) for the behavioral ratings plotted against time starting at time zero. For the immunoblotting data, the ratios of p-ERK2/ERK2, p-CREB/CREB, p-Akt/Akt, were plotted as previously described (Shi and McGinty 2007). Because of the less abundant level of p-ERK1 and because pERK2 has been identified as the isoform that mediates the neurochemical and behavioral effects of psychostimulants (Girault et al. 2007), only the pERK2/tERK2 ratio was analyzed. A one-way ANOVA was performed on the behavioral rating AUC for the AMPH pretreatment data. A two- way ANOVA was performed on the behavioral data on challenge day and on the immunoblotting ratio values. When an interaction effect of treatment was significant, Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison tests were used to reveal significant differences between the treatment groups. Prism 4.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) software was used for all statistical analyses.

Drugs

The drugs used were d-amphetamine sulfate (Sigma Chemical Co.), SCH23390, and eticlopride (RBI, Natick, MA). These drugs were dissolved in saline and were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) in a volume of 1 ml/kg. The drugs were calculated as the salt and freshly prepared on the day of the experiment.

RESULTS

Behavioral sensitization after repeated AMPH

In all AMPH pretreatment groups for experiments 1a and 2a (15 min experimental duration), motor activity was significantly greater on day 5 than on day 1 (Online Resource 1, Fig S1a). Similarly, in all AMPH pretreatment groups for experiments 1b and 2b (2 h experimental duration), the intensity of stereotypical behavior on day 5 was significantly greater than on day 1 (Online Resource 1, Fig S1b, p<0.0001), indicating the expression of behavioral sensitization to AMPH.

SCH23390 and eticlopride decreased behavior 15 min or 2 h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats

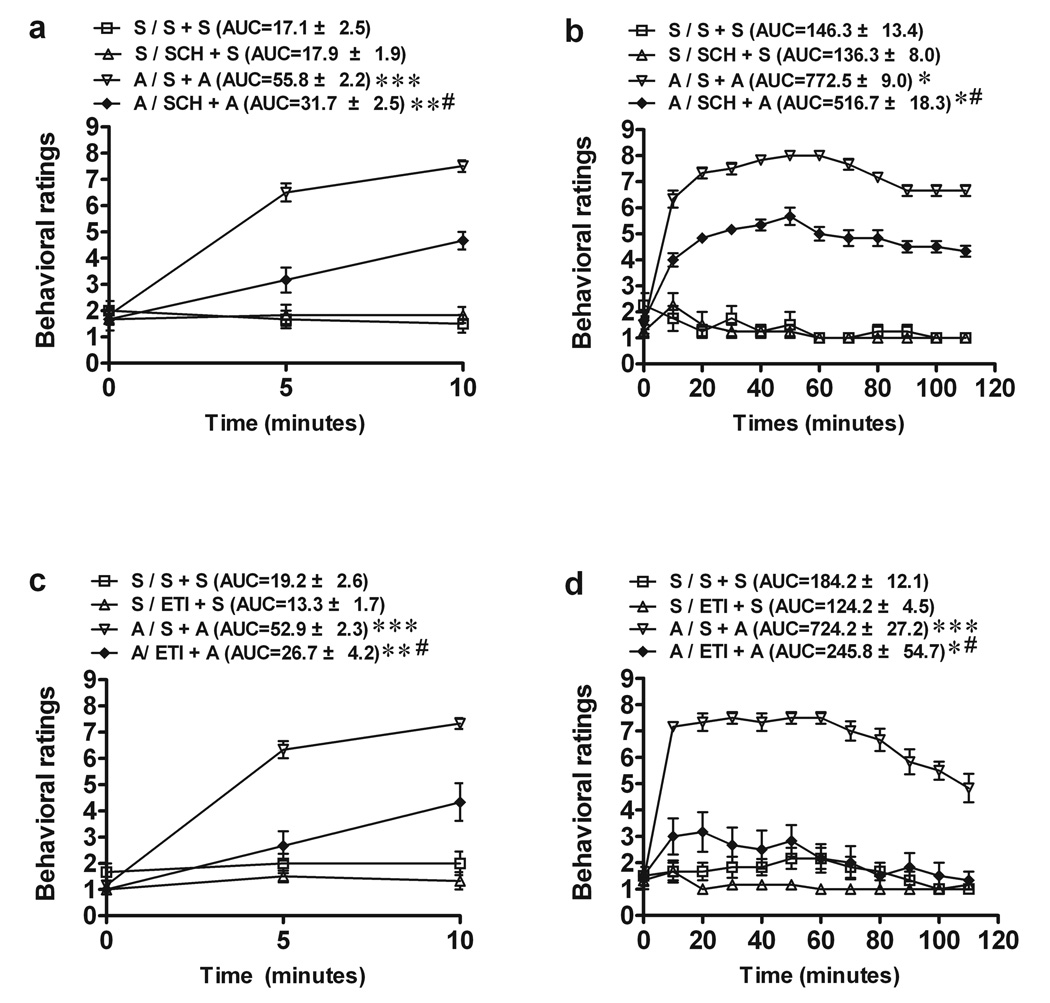

In experiments 1a and b, SCH23390 or saline was injected 15 min before a challenge injection. A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant drug × antagonist interaction (F1,20=29.9, p<0.0001). Pairwise comparisons showed that SCH 23390 did not affect spontaneous behavior in saline-treated rats but decreased the AMPH-induced increase in behavior in AMPH-sensitized rats at both 15 min (Experiment 1a: −28.8%, p<0.001) and 2 h (Experiment 1b: −33%, p<0.001) (Fig. 1a, b). In experiments 2a and b (Fig. 1 c, d), eticlopride or saline was injected 15 min before a challenge injection. A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant drug × antagonist interaction (F1,20=12.92, p<0.001). Pairwise comparisons showed that 0.1 mg/kg eticlopride did not affect spontaneous behavior in saline-treated rats but suppressed both stereotypical behavior and hyper-locomotion during both 15 min (Experiment 2a: −48.7%, p<0.001) and 2 h (Experiment 2b: −67.2%, p<0.001) sessions after the AMPH challenge injection. The mean rating ± SEM was 6.7 ± 0.3 for A/S+A and 2.2 ± 0.2 for A/SCH+A over the 2 h behavioral session.

Fig. 1.

The effects of SCH23390 (SCH-a, b) or eticlopride (ETI-c, d) on rat behavioral activity at 15 min (a, c) or 2h (b, d) after amphetamine (A) challenge (1 mg/kg, i.p.) in rats pretreated with AMPH (daily 5 mg/kg, i.p.) once daily for 5 days. (a, b) Pretreatment with SCH (0.01 mg/kg, i.p.) decreased behavioral ratings at 15 min (a) or 2 hr (b) after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. ** p <0.01 vs. S / SCH + S group; *** p <0.001 vs. S / S + S group; # p < 0.001 as compared with A / S + A group. (c), (d): Pretreatment with 0.1 mg/kg ETI attenuated behavioral ratings during both 15 min- and 2 h- period after the AMPH challenge. * p <0.05; ** p <0.01 vs. S / ETI + S group, *** p <0.001 vs. S / S + S group, # p < 0.001 as compared with A+ SAL + A group. *p <0.001 vs. S / S + S or S / SCH + S group. Values are expressed as means ± S.E.M. for 4– 6 rats per group. AUC, area under curve.

SCH23390 blocked ERK, CREB, and p Thr 308 - Akt phosphorylation in the striatum of AMPH-sensitized rats

To determine whether the blockade of D1 receptors prevents AMPH challenge-induced changes in phosphorylation in AMPH-sensitized rats, the levels of p-ERK, p-CREB, p-Thr308-Akt, and p-Ser473-Akt were measured using western blotting in rats from Experiment 1a and 1b whose behavior was described above. In Experiment 1a, SCH23390 prevented the induction of striatal p-ERK, p-CREB, and p-Thr308-Akt 15 min after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats but had no effect in the absence of AMPH (Fig. 2a–c). In contrast, the pSer473-Akt level was not altered 15 min after AMPH challenge (Fig. 2d). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant drug × antagonist interaction for p-ERK (F1,20=4.49, p<0.05), pCREB (F1,20=12.1, p<0.01) and pAkt (F1,20=9.51, p<0.01) expression 15 min after an AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. Pairwise comparisons after one-way ANOVA showed that SCH23390 significantly reduced the level of p-ERK (p<0.05), p-CREB (p<0.001), and p-Thr308-Akt (p<0.01) in this experiment.

Fig. 2.

Effects of pre-treatment with SCH23390 on the activation of striatal ERK1/2, CREB, and AktThr308 in AMPH-sensitized rats 15 min (a–d) or 2h (e–h) after challenge with AMPH. Upper panels show representative western blot bands, bottom panels show graphs plotted from data represented as mean ± S.E.M. of p-ERK2/ERK2 (a,e), p-CREB/CREB (b, f), p-Thr308-Akt (c, g), and p-Ser473-Akt (d, h) integrated density ratio (n=4–6 samples/group from three independent determinations). a: * p <0.05 vs. S / S + S group; # p <0.05 vs. A / S + A group. b: *** p <0.001 vs. S / S + S group; ### p <0.01 vs. A / S + A group. c: ** p <0.01 vs. S / S + S group; ## p <0.01 vs. A / S + A group. e: * p <0.05 vs. S / S + S group; # p <0.05 vs. A / S + A group. f: ** p <0.01 vs. S / S + S group; ## p <0.01 vs. A / S + A group. g: ** p <0.01 vs. S / S + S group.

In Experiment 1b, in accordance with our previous study (Shi and McGinty 2007), ERK and CREB phosphorylation was still elevated 2 h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats (Fig. 2e, f). Two-way ANOVA showed a significant drug × antagonist interaction for pERK (F1,16=4.83, p<0.05) and pCREB (F1,16=4.63, p<0.05). Pairwise comparisons showed that the increase in pERK and pCREB in striatum was blocked by SCH23390 pretreatment (p<0.05). In contrast, as previously reported (Shi and McGinty 2007), p-Thr308-Akt activation in the striatum was significantly reduced below saline control values 2 h after an AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats, but SCH23390 had no effect on the dephosphorylation of Thr308-Akt; two-way ANOVA showed a main effect of drug ((F1,16=0.016, p<0.001) but no interaction (Fig. 2g). In contrast, neither an AMPH challenge nor SCH23990 altered the levels of Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 2 h later (Fig. 2h).

Eticlopride did not alter AMPH-induced phosphorylation of striatal ERK, CREB or Akt but blocked the delayed Akt dephosphorylation in AMPH-sensitized rats

To determine whether the blockade of D2 receptors prevents AMPH challenge-induced changes in phosphorylation in AMPH-sensitized rats, the levels of p-ERK, p-CREB, p-Thr308-Akt, and p-Ser473-Akt were measured using western blotting in rats from Experiment 2a and 2b whose behavior was described above. In Experiment 2a, eticlopride by itself increased striatal p-ERK, p-CREB, and p-Thr308-Akt 15 min after a saline challenge. However, eticlopride had no effect on AMPH challenge-induced phosphoprotein increases in AMPH-sensitized rats (Fig. 3a–c). In contrast, the pSer473-Akt level was not altered by eticlopride or AMPH challenge (Fig. 3d). Two-way ANOVAs revealed significant drug × antagonist interactions on pERK (F1,20=6.75, p<0.05), and p-Thr308-Akt (F1,20=6.69, p<0.05) 15 min after an AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. For pCREB, two-way ANOVA showed a main effect of drug (F1, 20=11.72, p<0.001) or antagonist (F1, 20=5.72, p<0.05) but no interaction. Pairwise comparison tests showed that pretreatment with eticlopride significantly enhanced the phosphorylation of ERK, CREB, and Thr 308-Akt 15 min after a saline challenge in saline-pretreated rats (p<0.001; p<0.05; p<0.01, respectively) but did not alter the phosphoprotein induction 15 min after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats (Fig. 3a–c).

Fig. 3.

The blockade of D2 DA receptor with ETI (0.1 mg/kg. i.p.) elevated basal levels of striatal p-ERK (a), p-CREB (b), and p-Thr308-Akt (c) 15 min after SAL challenge injection, and prevented the downregulation of p-Thr308-Akt in AMPH-sensitized rats 2h (g) after challenge with AMPH, without alteration of other phosphoproteins activated by repeated AMPH. Representative immunoblots (upper panel) and quantitative analysis of phosphoproteins (lower panel). Data represented as means ± S.E.M of p-ERK2/ERK2 (a, e), p-CREB/CREB (b, f), p-Thr308-Akt (c, g), and p-Ser473-Akt (d, h) integrated density ratio (n=6 samples/group from three independent determinations). a: *** p <0.001 as compared with S / S + S group; ## p <0.01 as compared with S / S + S. b: * p <0.05 as compared with S / S + S group; # p <0.05 as compared with S /S + S. c: *** p <0.001 as compared with S / S + S group; ## p <0.01 as compared with S / S + S. e: *** p <0.001 as compared with groups challenge with saline. f: *** p <0.001 as compared with groups challenge with saline. g: *** p <0.001 as compared with groups challenge with saline, ##p <0.01 as compared with A / S + A group.

In Experiment 2b, phosphoprotein levels were back to baseline 2h after saline challenge in eticlopride pre-treated rats (Fig. 3e–g). Moreover, eticlopride failed to affect the sustained enhancement of p-ERK and p-CREB induced 2h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats (Fig. 3e, f). Two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of drug on pERK (F1,20=21.21, p<0.001) and pCREB. (F1,20=16.93, p<0.001). In contrast, a significant drug × antagonist interaction (F1,20=5.85, p<0.05) was revealed for p-Thr308-Akt 2h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. Pairwise comparison tests showed that the dephosphorylation of striatal p-Thr308-Akt in AMPH-sensitized rats was prevented by eticlopride pretreatment (p<0.01). Similar to the findings at 15 min, the phosphorylation of Ser473-Akt in the striatum was not altered 2 h after AMPH challenge injections in AMPH-sensitized rats.

Behavioral correlations with phosphoprotein changes

To determine whether changes in phosphoproteins are related to behavioral ratings in experiments 1b and 2b (2 hr timepoint), a regression analysis was used to obtain a Pearson’s correlation coefficient for phosphoproteins and behavioral ratings after AMPH challenge with or without antagonist pretreatment in AMPH-sensitized rats. A significant correlation was found between behavioral ratings and the phosphorylation of ERK and CREB in rat striatum 2 h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitize rats according to the presence or absence of SCH23390 in experiment 1b (Fig. 4a: r=0.66, p<0.05 for pERK); Fig. 4b: r=0.67, p<0.05 for pCREB). There was no significant correlation between behavioral ratings and the density of pAkt in this experiment (Fig. 4c). In contrast, no significant correlation was found between behavioral ratings and the phosphorylation of striatal ERK and CREB 2 h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitize rats with or without eticlopride in experiment 2b (Fig. 4d,e). However, behavior ratings in the presence or absence of eticlopride were significantly correlated with striatal decreases in pAkt 2 h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitize rats (Fig. 4f: r=−0.83, p<0.01).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of behavioral ratings and phosphoproteins 2 h after AMPH challenge injection in AMPH-sensitize rats. Fig. 4 a–c: Correlation of behavioral ratings and pERK (Fig 4a), pCREB (Fig. 4b), and pAkt (Fig. 4c) 2 h after AMPH challenge injection with (unfilled rectangle) or without SCH 23390 (filled rectangle) in AMPH-sensitize rats. (Fig. 4 d–e): Correlation of behavioral ratings and pERK (Fig. 4a), pCREB (Fig. 4b), and pAkt (Fig. 4c) 2 h after AMPH challenge injection with (unfilled rectangle) or without eticlopride (filled rectangle) in AMPH-sensitize rats. a: r=0.66, p<0.05; b: r=0.67, p<0.05; c: r=0.31, p>0.05; d: r=0.001, p>0.05; e: r=0.08, p>0.05; f: r=−0.84, p<0.01

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that 0.01 mg/kg of the D1 receptor-selective antagonist, SCH 23390, not only blocked the expression of stereotypical behavior, without affecting basal or AMPH-induced horizontal locomotor activity, but also prevented the early increase in ERK, CREB, and Thr308-Akt phosphorylation 15 min, as well as the prolonged enhancement of ERK and CREB phosphorylation 2 h, after an AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats. Furthermore, 0.1 mg/kg of the selective D2 receptor antagonist, eticlopride, markedly decreased locomotor and stereotypical behavior in AMPH-sensitized rats while preventing the delayed downregulation of Thr308-Akt phosphorylation in the striatum 2h after an AMPH challenge. As phosphorylation of both Thr308 and Ser473 is thought to be required for full kinase activity (Alessi et al. 1996, Manning and Cantley 2007), the level of Akt phosphrylation at Ser 473 was also examined in this study; however, no changes in p-Ser473-Akt were found among any groups in all the experiments.

SCH23390 and eticlopride differentially reduced the behavioral activation elicited by 1 mg/kg AMPH in AMPH-sensitized rats. Ratings between 6–8 on the behavioral rating scale represent repeated, focused stereotypical behaviors as described in Methods and in previous publications (Ellinwood and Balster 1974; Wang and McGinty 1995a; Shi and McGinty 2007). Thus, by decreasing behavioral ratings from a mean of 7.3 to a mean of 4.8, SCH23390 preferentially decreased stereotypical behaviors and not locomotor activity. Thus, D1 receptors are preferentially involved in the expression of the sensitized (stereotypical) component of the behavioral response after a low dose AMPH challenge in rats with an AMPH history. The fact that SCH23390 completely prevented the early (15 min) induction of ERK, CREB, and Thr308-Akt phosphorylation and the enduring (2 hr) increase in p-ERK and p-CREB induced by AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats supports a role for D1 receptor signaling via ERK and CREB in the stereotypical component of AMPH behavioral sensitization. In contrast, eticlopride decreased mean ratings in AMPH-treated rats from a mean of 6.7 to a mean of 2.2, indicating that blocking D2 receptors attenuated both AMPH-induced stereotypical and locomotor behavior. However, eticlopride had no effect on AMPH-induced ERK, CREB, or pThr308-Akt phosphorylation. Instead, eticlopride prevented the delayed de-phosphorylationo of Akt.

Because D1 and D2 receptors are predominantly segregated in striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons, respectively, in the dorsal striatum of rats (Gerfen 1992) and mice (Durieux et al. 2009; Valjent et al. 2009), it is likely that D1 receptor blockade primarily 17 affected direct pathway neurons and D2 receptor blockade affected indirect pathway neurons in the present study. This probability is supported by a recent study by Bertran-Gonzalez et al (2008) who reported that early ERK activation induced by a cocaine challenge in cocaine-sensitized mice remained restricted to D1 receptor-expressing neurons in the dorsal striatum (Bertran-Gonzalez et al. 2008). However, only the D1-dependent elevation of p-ERK and p-CREB endured as long as the behavioral activation in the present study, suggesting an association between the duration of phospho-protein elevation and the expression of sensitization. This association was also supported by a positive correlation between phosporylation of ERK and CREB and the behavioral ratings during 2h sessions after the AMPH challenge.

In contrast, Valjent and colleagues (2006) reported that inhibition of ERK phosphorylation immediately before a challenge injection of AMPH (or cocaine) did not block the expression of behavioral sensitization in mice. Further, in contrast to the lack of effect of eticlopride on AMPH- induced p-ERK and p-CREB in this study, Valjent et al (2000, 2004) demonstrated that the selective D2/D3 receptor antagonist, raclopride (0.3 mg/kg), which by itself increased p-ERK in the striatum, partially decreased acute cocaine-induced locomotor activity and ERK activation in the dorsal striatum of mice. Different outcomes in the Valjent studies are likely due to acute exposure to a different stimulant (cocaine), the antagonist dose, and/or the species used.

Although the phosphorylation of Akt at Thr308 and Ser473 is required for the enzyme's full activation, the kinases that target each site are different and their activation depends on the origin of the stimulation. Neurotrophin and insulin receptor stimulation can activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 to phosphorylate Akt at Thr308 in the kinase activation loop whereas mammalian target of rapamycin-RICTOR complex 2 phosphorylates Ser473-Akt in the carboxy terminal regulatory domain (Hresko et al. 2005; Song et al. 2005). However, in the present study, though phosphorylation of Akt at Thr308 was increased 15 minutes after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats, the level of Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 was not altered. Brami-Cherrier and colleagues (2002) reported an increase in p-Thr308-Akt, but not Ser473-Akt, after acute D1 or D2 agonist treatment. However, this increase was not PI3-K-dependent, suggesting that other intracellular signaling cascades, such as Wnt, regulate Akt (Fukumoto et al. 2001). In contrast, Izzo and colleagues (Izzo et al. 2002) reported that inhibition of PI3K blocked the expression, but not the induction, of behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Taken together, it appears that acute and repeated psychostimulant administration results in an immediate and transient D1R-dependent phosphorylation of Akt only at the Thr 308 residue. Whether or not a transient Thr308-Akt phosphorylation represents kinase activation is a question to be investigated in future studies. However, a recent report indicates that ischemia-induced activation only of Akt at Thr308 is not functionally active (Miyawaki et al. 2009).

Eticlopride significantly increased the basal levels of the three phospho-proteins in rats 15 min, but not 2 hr, after a saline challenge. There is abundant evidence that D2 receptor antagonists by themselves induce phospho-protein activation (Pozzi et al. 2003; Emamian et al. 2004; Valjent et al. 2004; Bertran-Gonzalez et al. 2008) in striatopallidal (indirect pathway) neurons. However, eticlopride did not significantly affect basal locomotor activity in saline-treated rats, suggesting that the transiently induced phosphoprotein activation did not affect behavioral activity. Dopamine D2 receptors are negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase and cyclic AMP production (Stoof and Kebabian 1981). Thus, the ability of eticlopride to increase ERK, CREB, and Thr308-Akt phosphorylation is most likely due to the removal of the inhibition exerted by dopamine D2 receptors on PKA signaling in D2 receptor-expressing (indirect pathway) neurons. Although eticlopride and AMPH separately induced high levels of p-ERK, p-CREB, and p-Thr308-Akt in rat striatum 15 min after saline or AMPH injection, respectively, the degree of increase in p-ERK and p-CREB levels induced by combined injection of the two drugs was not greater than the single injection of either drug. There are several possible explanations for this lack of an additive effect. Each drug may have induced maximal p-ERK and p-CREB levels, reaching a “ceiling” or saturated effect, if the increases were in the same neuronal population. Alternatively, activation of D1 receptors by AMPH in the presence of eticlopride may have indirectly suppressed p-ERK/p-CREB expression in D2-indirect pathway neurons by altering other local neurotransmitter systems, such as acetylcholine (Wang and McGinty, 1997). The opposite effect is also possible: blockade of D2 receptors may have transiently suppressed the ability of an AMPH challenge to increase p-ERK/p-CREB expression in D1-indirect pathway neurons. Since AMPH was able to increase p-ERK/p-CREB expression 2 hr after injection, the latter possibility seems to be more likely. In contrast, eticlopride prevented the delayed inactivation of striatal p-Thr308-Akt after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitized rats, suggesting that the downregulated p-Thr308-Akt in striatum was D2 receptor-dependent. Moreover, there was a significant negative correlation between behavioral ratings and the intensity of pAkt 2 h after AMPH challenge in AMPH-sensitize rats with or without eticlopride. Thus, emergence of p-Thr308-Akt dephosphorylation 2 h after AMPH stimulation suggests that Akt inactivation may be involved in turning off the behavioral response to AMPH. The delayed inactivation of Akt at Thr308, but not Akt Ser473, is consistent with the findings that a D2R/β-arrestin 2/PP2A complex regulates Thr308-Akt dephosphorylation in mice and the inability of AMPH to decrease p- Thr308-Akt in D2R knock-out mice (Beaulieu et al. 2005; 2007). In addition, Akt may be negatively regulated by the carboxy-terminal modulator protein, CTMP, that binds to the C-terminal of Akt and inactivates it (Miyawaki et al. 2009)) and/or the phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) that converts phosphoinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate to phosphoinositol 4,5-biphosphate, inhibiting Akt phosphorylation and activation (Maehama et al. 1998).

In conclusion, our findings that both D1 and D2 receptors contribute to the expression of behavioral sensitization, but D2 receptors are more selectively involved in stereotypical behaviors, induced by AMPH are consistent with previous studies that D1R in striatonigral neurons and D2R in striatopallidal neurons act synergistically to regulate the response to drugs of abuse (Ushijima et al. 1995, Romanelli et al. 2010). Of course, the involvement of dopamine receptors does not preclude the contribution of glutamate neurotransmission to behavioral sensitization (Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000) or to the activation of striatal phospho-proteins (Valjent et al. 2005) downstream from dopamine receptor activation. Further, the present study demonstrated that the early increase of phosphorylation in ERK1/2, Thr308-Akt and CREB, as well as sustained phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and CREB, induced by an AMPH challenge following repeated AMPH is mediated by D1 receptors. In contrast, a delayed decrease in Akt phosphorylation in AMPH-sensitized rats is mediated by D2 receptors. Further study is needed to determine the precise functional significance of p-ERK, p-CREB, and p-Akt fluctuations in the expression of AMPH sensitization in models, like BAC transgenic mice, that can differentiate the precise contribution of these phosphoproteins in direct and indirect striatal pathways.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by NIH RO1 DA03982 and CO6 RR015455

REFERENCES

- Alessi DR, Andjekovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings BA. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Sotnikova TD, Marion S, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. An Akt/β-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell. 2005;122:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Tirotta E, Sotnikova TD, Masri B, Salahpour A, Gainetdinov RR, et al. Regulation of Akt signaling by D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:881–885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5074-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran-Gonzalez J, Bosch C, Maroteaux M, Matamales M, Herve D, Valjent E, et al. Opposing patterns of signaling activation in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons in response to cocaine and haloperidol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5671–5685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1039-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brami-Cherrier K, Valjent E, Garcia M, Pages C, Hipskind RA, Caboche J. Dopamine induces a PI3-kinase-independent activation of Akt in striatal neurons: a new route to cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8911–8921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08911.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RL, Konradi C, Douglass JO, Hyman SE. Neuronal adaptation to amphetamine and dopamine: molecular mechanisms of prodynorphin gene expression in rat striatum. Neuron. 1995;14:813–823. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durieux PF, Bearzatto B, Guiducci S, Buch T, Waisman A, Zoli M, et al. D2R striatopallidal neurons inhibit both locomotor and drug reward processes. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:393–395. doi: 10.1038/nn.2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamian ES, Hall D, Birnbaum MJ, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3 β signaling in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellinwood EH, Jr, Balster RL. Rating the behavioral effects of amphetamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1974;28:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(74)90109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S, Hsieh CM, Maemura K, Layne MD, Yet SF, Lee KH, et al. Akt participation in the Wnt signaling pathway through Dishevelled. J Biol Chem. 2001;20:17479–17483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett BE, Holtzman SG. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor antagonists block caffeine-induced stimulation of locomotor activity in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;47:89–94. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. The neostriatal mosaic: multiple levels of compartmental organization. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:133–139. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90355-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girault JA, Valjent E, Caboche J, Herve D. ERK2: a logical AND gate critical for drug-induced plasticity. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hresko RC, Mueckler M. mTOR-RICTOR is the Ser473 kinase for Akt/Protein kinase B in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40406–40416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo E, Martin-Fardon R, Koob GF, Weiss F, Sanna PP. Neural plasticity and addiction: PI3-kinase and cocaine behavioral sensitization. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1263–1264. doi: 10.1038/nn977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE. Measurement of rodent stereotyped behavior. In: Crawley JN, Gerfen CR, Rogawski MA, Sibley DR, Skolnick P, Wray S, editors. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. pp. 8.8.1–8.8.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Stewart J. Dopamine transmission in the initiation and expression of psychostimulant-induced behavioral sensitization. Brain res Rev. 1991;16:223–244. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90007-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Pierce RC. The roles of calcium/calmodulin-dependent and Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinases in the development of psychostimulant-induced behavioral sensitization. J Neurochem. 2003;85:14–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki T, Ofengeim D, Noh K-M, Latuszek-Barrantes A, Hemmings BA, Follenzi A, Zukin RS. The endogenous inhibitor, CTMP, is critical to ischemia-induced neuronal death. Nature Neurosci. 2009;12:618–626. doi: 10.1038/nn.2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular mechanisms of drug addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi L, Hakansson K, Usiello A, Borgkvist A, Lindskog M, Greengard P, et al. Opposite regulation by typical and atypical anti-psychotics of ERK1/2, CREB and Elk-1 phosphorylation in mouse dorsal striatum. J Neurochem. 2003;86:451–459. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanelli RJ, Williams JT, Neve KA. Dopamine receptor signaling: Intracellular pathways to behavior. In: Neve KA, editor. The Dopamine Receptors. 2nd Ed. Totawa, NJ: Humana Press; 2010. pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JN, Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Repeated amphetamine administration induces a prolonged augmentation of phosphorylated cyclase response element binding protein and Fos-related antigen immunoreactivity in rat striatum. Neuroscience. 1995;69:441–4457. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00274-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, McGinty JF. Repeated amphetamine treatment increases phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase, protein kinase B, and cyclase response element-binding protein in the rat striatum. J Neurochem. 2007;103:706–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Ouyang G, Bao S. The activation of Akt/PKB signaling pathway and cell survival. J.Cell Mol.Med. 2005;9:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoof JC, Kebabian JW. Opposing roles for D-1 and D-2 dopamine receptors in efflux of cyclic AMP from rat neostriatum. Nature. 1981;294:366–368. doi: 10.1038/294366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima I, Carino MA, Horita A. Involvement of D1 and D2 systems in the behavioral effects of cocaine in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Beh. 1995;52:737–741. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00167-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corvol J-C, Pages C, Besson M-J, Maldanado R, Caboche J. Involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade for cocaine-rewarding properties. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8701–8709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08701.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Pages C, Herve D, Girault J-A, Caboche J. Addictive and non-addictive drugs induce distinct and specific patterns of ERK activation in mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1826–1836. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Pascoll V, Svenningsson P, Paul S, Corvol J-C, Stipanovich A, et al. Regulation of a protein phosphatase cascade allows convergent dopamine and glutamate signals to activate ERK in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:491–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408305102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corvol J-C, Trzaskos JM, Girault J-A, Herve D. Role of the ERK pathway in psychostiimulant-induced locomotor sensitization. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Bertran-Gonzalez J, Hervé D, Fisone G, Girault JA. Looking BAC at striatal signaling: cell-specific analysis in new transgenic mice. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Kalivas PW. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: a critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151:99–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Alterations in striatal zif/268, preprodynorphin and preproenkephalin mRNA expression induced by repeated amphetamine administration in rats. Brain Research. 1995a;673:262–274. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01422-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. Differential effects of D1 or D2 dopamine receptors antagonists on acute amphetamine- and methamphetamine-induced upregulation of zif/268 mRNA expression in rat forebrain. J Neurochem. 1995b;65:2706–2715. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. The full D1 dopamine receptor agonist SKF-82958 induces neuropeptide mRNA in the normosensitive striatum of rats: Regulation of D1/D2 interactions by muscarinic receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:972–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Jeziorski M. Coadministration of MK-801 with amphetamine, cocaine or morphine prevents rather than transiently masks the development of behavioral sensitization. Brain Res. 1993;613:291–294. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90913-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME, Sun X, Mangiavacchi S, Chao SZ. Psychomotor stimulants and neuronal plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Feng J, Fienberg AA, Greengard P. D(2) dopamine receptors induce mitogen-activated protein kinase and cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11607–11612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lou D, Jiao H, Zhang D, Wang X, Xia Y, et al. Cocaine-induced intracellular signaling and gene expression are oppositely regulated by the dopamine D1and D3 receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3344–3354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0060-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.