Abstract

Phosphatidylserine exposure occurs in red blood cells (RBCs) from sickle cell disease (SCD) patients and is increased by deoxygenation. The mechanisms responsible remain unclear. RBCs from SCD patients also have elevated cation permeability, and, in particular, a deoxygenation-induced cation conductance which mediates Ca2+ entry, providing an obvious link with phosphatidylserine exposure. The role of Ca2+ was investigated using FITC-labelled annexin. Results confirmed high phosphatidylserine exposure in RBCs from SCD patients increasing upon deoxygenation. When deoxygenated, phosphatidylserine exposure was further elevated as extracellular [Ca2+] was increased. This effect was inhibited by dipyridamole, intracellular Ca2+ chelation, and Gardos channel inhibition. Phosphatidylserine exposure was reduced in high K+ saline. Ca2+ levels required to elicit phosphatidylserine exposure were in the low micromolar range. Findings are consistent with Ca2+ entry through the deoxygenation-induced pathway (Psickle), activating the Gardos channel. [Ca2+] required for phosphatidylserine scrambling are in the range achievable in vivo.

1. Introduction

Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) display a range of symptoms which include chronic anemia together with ischemic pain and organ damage [1]. The underlying cause is the presence in patients' red blood cells (RBCs) of the abnormal hemoglobin, HbS [2]. HbS polymerises into rigid rods on deoxygenation, changing RBC shape from biconcave disc into the characteristic sickle appearance [3]. RBC membrane permeability is markedly abnormal [4] whilst HbS is also unstable, representing an oxidative threat [5]. Altered behaviour of these HbS-containing RBCs (here termed HbS cells), other circulating cells, and the endothelium combine to reduce RBC lifespan (hence the anemia) and also result in microvascular occlusion (hence the ischemia) [6]. Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, an important feature is considered to be increased exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer bilayer of the RBC membrane [7–10]. Externalised PS is prothrombotic, and also provides a potential adhesion site for both macrophages and activated endothelial cells, contributing to both reduced HbS cell lifespan and vascular occlusion [11–13].

Two membrane phospholipid transporters represent the major determinants of PS exposure in RBCs: the ATP-dependent aminophospholipid translocase (APLT or flippase) transports aminophospholipids (APs), including PS, from outer to inner leaflet, whilst the Ca2+-dependent scramblase moves APs rapidly in both directions thus disrupting phospholipid asymmetry [14]. In normal RBCs, PS is largely confined to inner leaflet, through the dominant action of the flippase whilst the scramblase remains quiescent. A small, but variable, proportion of HbS cells from sickle cell patients, however, show exposure of PS ranging from about 2–10% [7, 9, 15, 16]. Both flippase inhibition and activation of the scramblase are probably involved [17]. Flippase inhibition could follow oxidative stress [18, 19], whilst scramblase activation could be caused by raised intracellular Ca2+ (e.g., [19, 20]) or other stimuli (e.g., [21]). The exact mechanisms, however, remain uncertain.

It is also well established that deoxygenation of HbS in vitro results in increased PS exposure [22, 23] but, again, the mechanism is not clear. Possibilities include disruption of the spectrin cytoskeleton [24], ATP depletion [25], decrease in intracellular Mg2+ [26], and also a rise in intracellular Ca2+ [20, 26]. In many reports concerning PS exposure, however, Ca2+ is not controlled or is present at unphysiological levels, making it difficult to assess its role definitively. In addition, whilst a more recent study correlated PS exposure in HbS cells with flippase inhibition, rather than elevation of intracellular Ca2+, the effects of deoxygenation were not determined [9].

Deoxygenation of HbS cells as well as causing HbS polymerisation and shape change, also activates a permeability pathway termed Psickle [4, 27]. Psickle is often described as a deoxygenation-induced cation conductance, apparently unique to HbS-containing red cells. A major importance of Psickle is its permeability to Ca2+ [28, 29]. Although Ca2+ entry via this pathway represents an obvious link between HbS polymerisation and the deoxygenation-induced PS exposure, estimates suggest that the magnitude to which Ca2+ may be elevated is still relatively modest (around 100 nM) [29], and several orders of magnitude below that required for scramblase activation (around 100 μM is usually cited [20, 30–32]). The present work is aimed at assessing the role of Ca2+ in PS exposure in RBCs from sickle cell patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood

Anonymised, discarded, routine blood samples (taken into the anticoagulant EDTA) were collected from individuals homozygous for HbS (HbSS genotype, n = 62) with approval from the local Ethics committee. After withdrawal, blood samples were kept refrigerated until used. (RBCs from HbSS individuals are here termed HbS cells).

2.2. Salines and Chemicals

HbS cells were washed into low (LK) or high potassium- (HK-) containing saline, comprising (in mM) NaCl 140, KCl 4, glucose 5, HEPES 10 for LK saline, and NaCl 55, KCl 90, glucose 5 and HEPES 10 for HK saline, all pH 7.4 at 37°C, with different extracellular [Ca2+]s ([Ca2+]os) as indicated. When required, inhibitors (clotrimazole, DIDS, and dipyridamole) were added from stock solutions in DMSO. In these experiments, DMSO (final concentration 0.5%) was also added to controls. To investigate the effect of Ca2+ chelation, MAPTAM (5 μM; Calbiochem, UK) was loaded into RBCs (5% haematocrit) for 60 min at 37°C with added pyruvate (5 mM) to prevent inhibition of glycolysis [33]. Extracellular chelator was removed by washing once with saline. Control RBCs without chelator were handled in the same way. FITC-labelled annexin V was obtained from Becton-Dickinson (Oxford, UK) in aqueous stock solutions (final concentration 0.3 μg·mL−1). The calmodulin inhibitor N-(6-aminohexyl)-5-chloro-1-naphthalene sulphonamide (W-7) and the calcium fluorophore fluo-4-AM came from Invitrogen; all other reagents were obtained from Sigma (Poole, UK).

2.3. Control of O2 Tension, Measurement of PS Exposure and Intracellular Ca2+

Salines and HbS cell suspensions were first equilibrated with humidified air (oxygenated) or N2 (deoxygenated) in Eschweiler tonometers (Eschweiler, Kiel, Germany). They were then placed in 24-well plates (108 cells·mL−1, depth 3 mm) at 37°C in humidified incubators flushed with room air or 1% O2 (using a Galaxy-R oxygen incubator, RS Biotech, Irvine, UK) for 3–18 hours. After incubation, RBCs were treated with vanadate (1 mM) to inhibit flippase activity. They were then immediately harvested, washed once, and resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells·mL−1 in binding annexin buffer (composition in mM: 145 NaCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature with FITC-labelled annexin (0.3 μg·mL−1). Unattached annexin was then removed by washing once followed by resuspension in 5-times the initial volume of ice-cold binding buffer, after which samples were placed on ice. Percentage of RBCs with PS exposed on their external membrane was then measured in the FL-1 channel of a fluorescence-activated flow cytometer (FACSCalibur, BD), in which negative fluorescent gate was set using cells exposed to FITC-labelled annexin but in the absence of Ca2+ (which prevents annexin binding). PS exposure here refers to the percentage of RBCs which fluoresce more brightly than the negative gate. To alter intracellular [Ca2+], RBCs at 1% Hct were exposed to the calcium ionophore bromo-A23187 (1–6 μM), vanadate (1 mM), EDTA (2 mM), and different [Ca2+]os for 30 min to achieve the requisite final [Ca2+]o [34]. This was multiplied by the square of Donnan ratio, r 2([H+]i/[H+]o)2 = 2.05 [35, 36], to calculate [Ca2+]i. After 30 min, RBCs were treated with Co2+ (0.4 mM, to block A23187) after which they were processed for annexin-labelling, as above. Annexin was used to label PS because it is important to compare findings with extensive reports in the literature using this PS marker (e.g., [8, 19, 37–39]). Bromo-A23187 (in preference to A23187 per se) was used because it does not fluoresce. These experiments were carried out in LK or HK saline, composition as above except for the addition of 0.15 mM MgCl2 to keep intracellular [Mg2+] at physiological levels. Finally, to show Ca2+-loading of RBCs, cells were loaded with fluo-4-AM (30 min at 37°C, 5 μM; then washed once) with fluo-4 fluorescence also then measured in the FITC channel by FACS.

2.4. Statistics

Unless otherwise stated, data are presented as means ± S.E.M. for blood samples from n patients. Statistical significance of any differences was tested using paired Student's t-test (with P < .05 taken as significant).

3. Results

3.1. The Effect of Ca2+ on PS Exposure

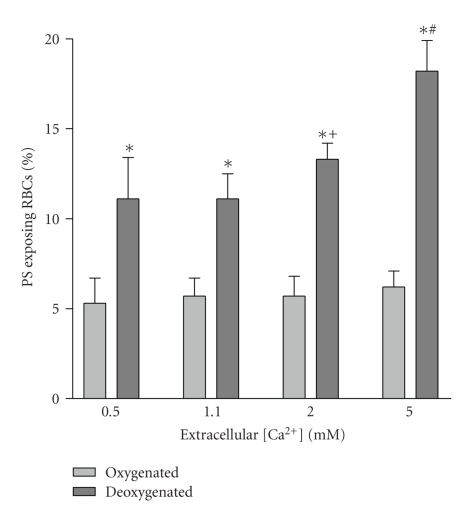

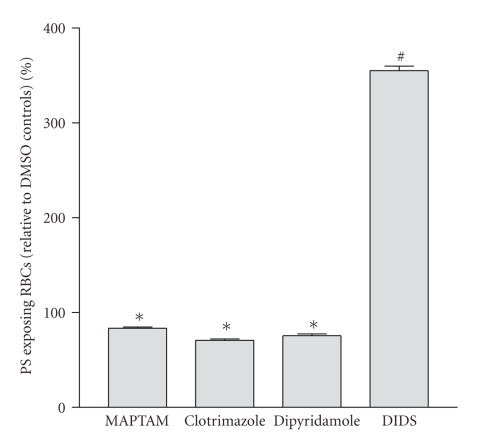

PS exposure in HbS cell samples taken from SCD patients and immediately labelled with FITC-annexin ranged from 0.4 to 16.0% with a mean of 2.3 ± 0.5% (n = 36). The effect of different [Ca2+]os (0.1, 0.5, 1.1, 2 and 5 mM) on the percentage of HbS cells showing PS exposure was then investigated. In oxygenated (20% O2) HbS cells, PS exposure was lower and although the extent of exposure was augmented when RBCs were incubated at higher [Ca2+]os, the effect was small and not significant (Figure 1). When cells were deoxygenated (1% O2), PS exposure was always higher than that observed in oxygenated HbS cells. There was also a marked increase in PS at the higher [Ca2+]os (Figure 1). This effect was present within 30 min, with longer incubation periods increasing the effect. To determine whether Ca2+ was acting extracellularly or intracellularly, HbS cells were loaded with the Ca2+ chelator MAPTAM prior to deoxygenation (Figure 2). Over a 3 hour period, MAPTAM decreased the percentage of positive HbS cells (P < .01). This inhibitory effect did not persist over an 18 hour incubation, probably because the available cytoplasmic MAPTA becomes saturated with Ca2+.

Figure 1.

Effect of oxygen tension and extracellular Ca2+ on phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure in red blood cells (RBCs) from sickle cell patients. RBCs were incubated for 18 hours at four extracellular [Ca2+]'s (0.5, 1.1, 2.0 and 5.0 mM) after which they were labelled with FITC-annexin (as described in Section 2). Histograms representing mean percentage of positive RBCs ± S.E.M. for 5 different patients. *P < .01 deoxy compare to oxy; + P < .05 cf 0.5 mM Ca2+ deoxy; # P < .01 cf 0.5 mM Ca2+ deoxy.

Figure 2.

Effect of inhibitors on phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure in red blood cells (RBCs) from sickle cell patients. RBCs were incubated under deoxygenated conditions (1% O2) for 3 hours (5 mM extracellular [Ca2+]) after which they were labelled with FITC-annexin. Four conditions (all with 0.5% DMSO) are shown: MAPTAM-treated RBCs (loaded with 5 μM MAPTAM prior to deoxygenation), clotrimazole (10 μM), dipyridamole (50 μM), and DIDS (50 μM). Results are presented as percentage PS exposing RBCs relative to control RBCs exposed to 0.5% DMSO only. Histograms represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 3). *P < .01 and # P < .0001 cf DMSO controls.

3.2. Effect of Partial Psickle Inhibitors on PS Exposure

Although there are no specific inhibitors of Psickle, dipyridamole is partially effective [40]. When present during deoxygenation, dipyridamole (50 μM) reduced PS exposure in deoxygenated HbS cells (Figure 2; P < .01), consistent with Ca2+ entry via Psickle stimulating exposure. DIDS, although better known as a band 3 inhibitor, is also a partial Psickle inhibitor [41]. Addition of DIDS (50 μM), however, produced a marked increase in PS exposing RBCs with percentage of positive RBCs increasing several folds (Figure 2; P < .01). When DIDS was added to RBCs from normal HbAA individuals, PS exposure was also similarly increased: to 95.0 ± 0.3% in oxygenated conditions, and to 98.7 ± 0.1% in deoxygenated cells (both means ± S.E.M., n = 3). These findings suggest that annexin binding was caused by DIDS reacting with its target on the RBC membrane. HbS cells exposed to DIDS, but not subsequently treated with FITC-annexin, did not fluoresce (e.g., 0% DIDS-treated without FITC-annexin cf 50% DIDS-treated with annexin), indicating that the high values were not due to fluorescence from DIDS itself.

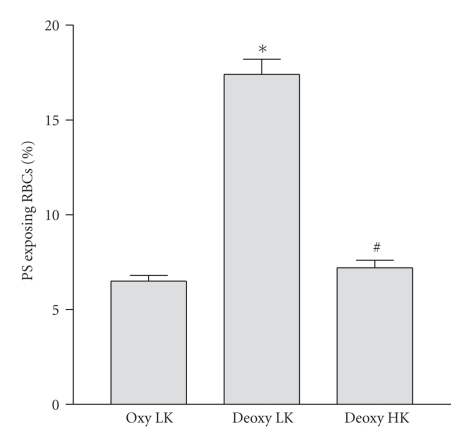

3.3. PS Exposure and Red Cell Shrinkage

Elevated intracellular Ca2+ activates the Gardos channel and leads to K+ loss with Cl− following through separate Cl− channels [4]. PS exposure could therefore be secondary to the ensuing cell shrinkage [37]. To investigate this possibility, HbS cells were suspended in high K+-containing saline (90 mM) to remove any gradient for K+ efflux. The deoxygenation-induced increase in PS exposure was abolished (Figure 3), with values reduced to those observed in oxygenated samples (P < .001 deoxy LK cf oxy LK; N.S. deoxy HK cf oxy LK). An estimate of RBC size is provided by FACS forward scatter measurement. Forward scatter was 487 ± 8 (means ± S.E.M., n = 3) in oxygenated LK saline, falling to 439 ± 4 in deoxygenated LK saline (P < .005). In deoxygenated HK saline a value of 497 ± 3 was obtained (N.S. cf. oxygenated LK saline). PS exposure following deoxygenation in LK saline was therefore accompanied by cell shrinkage. This was not observed during deoxygenation in high K+ saline. A second method of inhibiting the Gardos channel, treatment with clotrimazole (10 μM), was also tested. In this case, however, PS exposure was only partially prevented (Figure 2; P < .01).

Figure 3.

Effect of extracellular K+ on phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure in red blood cells (RBCs) from sickle cell patients. RBCs were incubated for 18 hours with extracellular [Ca2+] of 5 mM under oxygenated (20% O2) or deoxygenated (1% O2) conditions in either low K+-containing (extracellular [K+] of 5 mM) saline or high K+-containing (90 mM [K+]) saline. Histograms represent means ± S.E.M. (n = 3). *P < .001 compare to LK oxy; #N.S. cf. LK oxy.

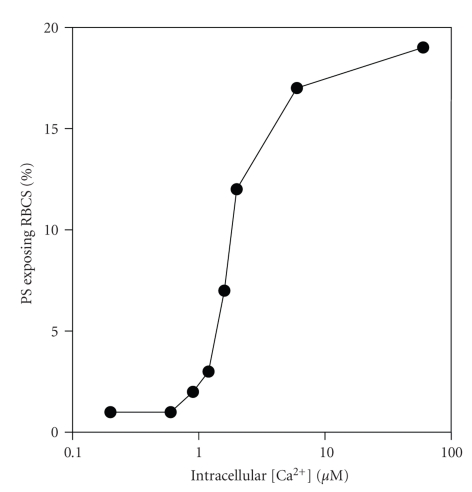

3.4. PS Exposure and Direct Manipulation of Intracellular [Ca2+]

Treatment of RBCs with the divalent cation ionophore bromo-A23187 was used to alter intracellular [Ca2+] directly [34, 35]. RBCs were initially treated with vanadate (1 mM), to inhibit both the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump and also the flippase. Following 30 min incubation with bromo-A23187 to alter [Ca2+]i, Co2+ (0.4 mM) was then added to block Ca2+ permeability via A23187 thereby keeping intracellular [Ca2+] constant during annexin labelling (for which 2.5 mM extracellular [Ca2+] is required). Results are shown in Figure 4. PS exposure is elicited as [Ca2+]i increased above about 600 nM. A sigmoidal dependence of PS exposure with [Ca2+] was then apparent with an EC50 of 1.31 ± 0.84 μM (n = 6). Peak exposures varied from 16–46%, mean 28 ± 5 (n = 6) with a plateau reached at about 10 μM and without further change at higher [Ca2+]is ([Ca2+]s up to 600 μM were tested).

Figure 4.

Effect of manipulation of intracellular Ca2+ on phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure in red blood cells (RBCs) from sickle cell patients. RBCs were first treated with vanadate (1 mM) to inhibit the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump and also the aminophospholipid translocase (flippase) before addition of bromo-A23187 (1.2 μM, 1% haematocrit) and requisite extracellular [Ca2+]s for 30 min. They were then treated with Co2+ (0.4 mM) before labelling with FITC-annexin. Intracellular [Ca2+] is calculated from extracellular [Ca2+] × r 2, where r 2 was taken as 2.05 [36]. Results presented are from a single experiment representative of 5 others.

3.5. Modulation of PS Exposure

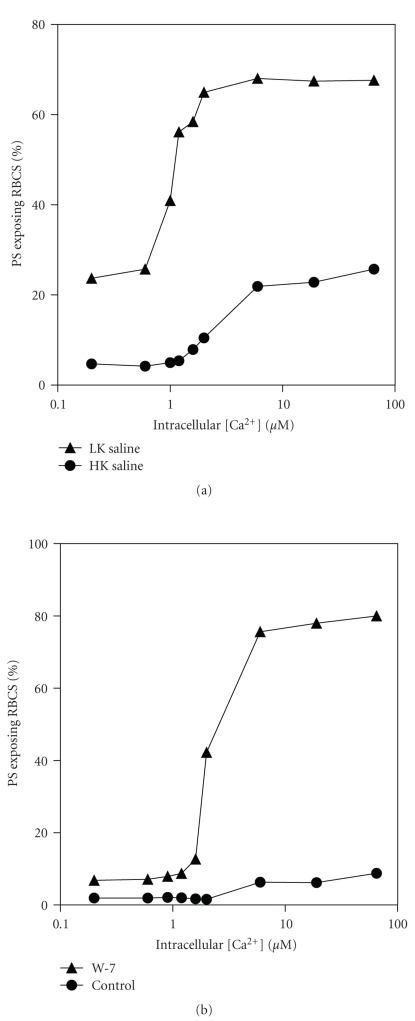

In the preceding section, although high affinity Ca2+-induced scrambling was present, it was noticeable that nevertheless only a minority of all RBCs stained positively for PS using FITC-annexin—as is also found in many literature reports, for example, [39]. That Ca2+ loading was complete and homogeneous was first ascertained using intracellular fluo-4 (Figure 5). It is apparent that the majority of RBCs (98 ± 1%, n = 3) were Ca2+-loaded. Uneven Ca2+ loading can therefore be discounted. As K+ has been reported to inhibit PS scrambling [42], the effect of 30 min incubation in LK saline compared to HK was determined in the presence of bromo-A23187 and different [Ca2+]. LK saline was found to increase the percentage of positive cells (Figure 6(a)), an effect again partially inhibited by clotrimazole (10 μM) which, for example, reduced percentage of positive cells from 44% to 28% at 10 μM Ca2+. Finally, the effect of the calmodulin inhibitor W-7 was tested (Figure 6(b)). In this case, the percentage of positive RBCs increased. It was noticeable, however, that in all these manoeuvres, Ca2+ affinity was unaffected (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Ca2+ loading of red blood cells (RBCs) from sickle cell patients. RBCs were loaded with the Ca2+ fluorophore fluo-4 (see Methods). They were then incubated for 30 min in the absence (left—thin line) or presence (right—thick line) of bromo-A23187 at an extracellular [Ca2+] of 1 μM. Results are presented as histogram of fluorescence of a single experiment representative of 3.

Figure 6.

Effect of K+ and calmodulin inhibition on Ca2+-induced exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) in red blood cells (RBCs) from sickle cell patients. Experimental details were as described in the legend to Figure 4, except that in (a) where incubation was carried out in either high K+-(HK, K+ = 90 mM) or low K+-containing saline (LK, 4 mM), and, in (b) where HK saline was used in the absence or presence of W-7 (100 μM). Results are presented as single experiments representative of 3 others.

4. Discussion

Whilst it is well known that RBCs from SCD patients show elevated levels of PS exposure and that these are increased upon deoxygenation, the mechanism is not clear. The present results explore more fully that the role of Ca2+. Ca2+ concentrations required for scrambling is considerably lower than previously appreciated. The Ca2+ affinity of the scrambling process is not dissimilar to that associated with inhibition of flippase activity or activation of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel (Gardos channel). This important finding suggests coordination of these eryptotic events. Results also implicate a role for RBC shrinkage and shape change.

4.1. Role of Ca2+ and Psickle on PS Exposure

Altering extracellular Ca2+ levels had little effect on PS exposure in oxygenated HbS cells. Under deoxygenated conditions, however, PS exposure increased with [Ca2+]o. This effect was partially inhibited by dipyridamole [40] and by intracellular Ca2+ chelation with MAPTAM treatment [34]. These findings are consistent with Ca2+ entering via the deoxygenation-induced pathway Psickle [4, 27] and acting intracellularly. Intracellular Ca2+ can have several actions. First, it will activate the Gardos channel leading to RBC shrinkage [43]. Second, it may stimulate the Ca2+-dependent scramblase whilst inhibiting the ATP-dependent flippase [14]. Third, it may stimulate cysteine proteases [44]. Any of these events may lead to PS exposure [21]. Several manoeuvres were tested to separate these possibilities. The most effective way of inhibiting PS exposure was incubation in high K+ saline. Removal of the electrochemical gradient for K+ efflux abolished the deoxygenation-induced increase in PS exposure. The Gardos channel inhibitor clotrimazole also partially inhibited PS exposure. Findings are consistent with the hypothesis that activation of Psickle, by deoxygenation mediates Ca2+ entry, elevating [Ca2+]i which then promotes PS exposure by Gardos channel activation, loss of intracellular solutes, and red cell shrinkage. Importantly, high K+ salines were effective over all incubation times (up to 18 hours). Shrinkage has been shown previously to stimulate PS exposure in both normal RBCs and HbS cells [37, 45] and would appear to be involved in deoxygenation-induced PS exposure in sickle cells.

4.2. Ca2+ Dependence of PS Exposure

A major aim of this work was to determine unequivocally the intracellular Ca2+ required to elicit PS exposure in HbS cells. This was investigated using RBCs loaded with different [Ca2+]s using bromo-A23187. RBCs were first treated with vanadate (to inhibit both the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump and the flippase) and subsequently with Co2+ (which blocks A23187 so that the relatively high [Ca2+] required for annexin binding, 2.5 mM, could not gain access to the cytoplasm). Results showed that PS exposure was stimulated by micromolar Ca2+ concentrations with an EC50 of about 1.2 μM. This concentration is similar, though slightly higher, compared with that required for half-maximal activation of the Gardos channel activation [46, 47] and for inhibition of the flippase [26]. A similar high affinity for Ca2+ was also observed in RBCs incubated in LK saline indicating that high K+ levels are not responsible for these observations. Calmodulin is known to interact with RBC cytoskeleton and influence PS exposure [48, 49]. Incubation with the calmodulin antagonist W-7 again showed a similar high Ca2+ affinity for PS exposure. In this case, the percentage of positive cells was also increased so that the majority of RBCs became positive, showing that most RBCs are capable of PS scrambling at these low Ca2+ levels. Previously reported values for activation of the scramblase are considerably higher than those given here, with values of 25–100 μM quoted [14, 32]. Previous measurements, however, were made largely on resealed RBC ghosts, inside-out vesicles, or purified PLSCR1 [30, 31, 50, 51], which may not in fact represent the RBC scramblase [52]. These preparations will also necessarily lack much of the cytoplasmic contents which may result in reduction in Ca2+ affinity of the scrambling process. Furthermore, several previous reports were carried out in the presence of high concentrations of extracellular Mg2+ (1 mM) [20, 30, 50], which with the ionophore A23187 would set intracellular Mg2+ at over 2 mM, considerably in excess of the normal RBC [Mg2+] [53], and which might be expected to dampen any Ca2+ driven process. We speculate that having a similar Ca2+ level for Gardos channel activation, flippase inhibition and activation of scrambling would coordinate eryptotic events [21] and facilitate removal damaged RBCs in normal individuals, whilst in SCD patients, hyperactivity of these processes may contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Authorship Contributions

The paper was designed by J. S. Gibson and D. C. Rees and carried out by E. Weiss. E. Weiss and J. S. Gibson analysed the data. J. S. Gibson wrote the paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the British Heart Foundation and the Medical Research Council Trust for financial support.

References

- 1.Steinberg MH. Sickle cell anemia, the first molecular disease: overview of molecular etiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2008;8:1295–1324. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauling L, Itano HA, Singer SJ, Wells IC. Sickle cell anemia, a molecular disease. Science. 1949;110(2865):543–548. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2865.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunn HF, Forget BG. Hemoglobin: Molecular, Genetic and Clinical Aspects. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Saunders; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lew VL, Bookchin RM. Ion transport pathology in the mechanism of sickle cell dehydration. Physiological Reviews. 2005;85(1):179–200. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00052.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebbel RP, Morgan WT, Eaton JW, Hedlund BE. Accelerated autoxidation and heme loss due to instability of sickle hemoglobin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85(1):237–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hebbel RP. Beyond hemoglobin polymerization: the red blood cell membrane and sickle disease pathophysiology. Blood. 1991;77(2):214–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tait JF, Gibson D. Measurement of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in normal and sickle-cell erythrocytes by menas of annexin V binding. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1994;123(5):741–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuypers FA, Lewis RA, Hua M, et al. Detection of altered membrane phospholipid asymmetry in subpopulations of human red blood cells using fluorescently labeled annexin V. Blood. 1996;87(3):1179–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Jong K, Larkin SK, Styles LA, Bookchin RM, Kuypers FA. Characterization of the phosphatidylserine-exposing subpopulation of sickle cells. Blood. 2001;98(3):860–867. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Setty BNY, Kulkarni S, Stuart MJ. Role of erythrocyte phosphatidylserine in sickle red cell-endothelial adhesion. Blood. 2002;99(5):1564–1571. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebbel RP, Boogaerts MAB, Eaton JW, Steinberg MH. Erythrocyte adherence to endothelium in sickle-cell anemia. A possible determinant of disease severity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1980;302(18):992–995. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu D, Lubin B, Roelofsen B, Van Deenen LLM. Sickled erythrocytes accelerate clotting in vitro: an effect of abnormal membrane lipid asymmetry. Blood. 1981;58(2):398–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setty BNY, Betal SG. Microvascular endothelial cells express a phosphatidylserine receptor: a functionally active receptor for phosphatidylserine-positive erythrocytes. Blood. 2008;111(2):905–914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haest CWM. Distribution and movement of membrane lipids. In: Bernhardt I, Ellory JC, editors. Red Cell Membrane Transport in Health and Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2003. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood BL, Gibson DF, Tait JF. Increased erythrocyte phosphatidylserine exposure in sickle cell disease: flow-cytometric measurement and clinical associations. Blood. 1996;88(5):1873–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuypers FA. Phospholipid asymmetry in health and disease. Current Opinion in Hematology. 1998;5(2):122–131. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barber LA, Palascak MB, Joiner CH, Franco RS. Aminophospholipid translocase and phospholipid scramblase activities in sickle erythrocyte subpopulations. British Journal of Haematology. 2009;146(4):447–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devaux PF, Zachowski A. Maintenance and consequences of membrane phospholipid asymmetry. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 1994;73(1-2):107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Jong K, Geldwerth D, Kuypers FA. Oxidative damage does not alter membrane phospholipid asymmetry in human erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 1997;36(22):6768–6776. doi: 10.1021/bi962973a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williamson P, Kulick A, Zachowski A, Schlegel RA, Devaux PF. Ca2+ induces transbilayer redistribution of all major phospholipids in human erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 1992;31(27):6355–6360. doi: 10.1021/bi00142a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang F, Lang KS, Lang PA, Huber SM, Wieder T. Mechanisms and significance of eryptosis. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2006;8(7-8):1183–1192. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiu D, Lubin B, Shohet SB. Erythrocyte membrane lipid reorganization during the sickling process. British Journal of Haematology. 1979;41(2):223–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1979.tb05851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubin B, Chiu D, Bastacky J. Abnormalities in membrane phospholipid organization in sickled erythrocytes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1981;67(6):1643–1649. doi: 10.1172/JCI110200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franck PFH, Bevers EM, Lubin BH, et al. Uncoupling of the membrane skeleton from the lipid bilayer. The cause of accelerated phospholipid flip-flop leading to an enhanced procoagulant activity of sickled cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1985;75(1):183–190. doi: 10.1172/JCI111672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Middelkoop E, Lubin BH, Bevers EM, et al. Studies on sickled erythrocytes provide evidence that the asymmetric distribution of phosphatidylserine in the red cell membrane is maintained by both ATP-dependent translocation and interaction with membrane skeletal proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1988;937(2):281–288. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bitbol M, Fellmann P, Zachowski A, Devaux PF. Ion regulation of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine outside-inside translocation in human erythrocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1987;904(2):268–282. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joiner CH. Cation transport and volume regulation in sickle red blood cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;264(2):C251–C270. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.2.C251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhoda MD, Apovo M, Beuzard Y, Giraud F. Ca2+ permeability in deoxygenated sickle cells. Blood. 1990;75(12):2453–2458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Etzion Z, Tiffert T, Bookchin RM, Lew VL. Effects of deoxygenation on active and passive Ca2+ transport and on the cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels of sickle cell anemia red cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;92(5):2489–2498. doi: 10.1172/JCI116857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verhoven B, Schlegel RA, Williamson P. Rapid loss and restoration of lipid asymmetry by different pathways in resealed erythrocyte ghosts. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1992;1104(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassé F, Stout JG, Sims PJ, Wiedmer T. Isolation of an erythrocyte membrane protein that mediates Ca2+-dependent transbilayer movement of phospholipid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(29):17205–17210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamp D, Sieberg T, Haest CWM. Inhibition and stimulation of phospholipid scrambling activity. Consequences for lipid asymmetry, echinocytosis, and microvesiculation of erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 2001;40(31):9438–9446. doi: 10.1021/bi0107492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Sancho J. Pyruvate prevents the ATP depletion caused by formaldehyde or calcium-chelator esters in the human red cell. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1985;813(1):148–150. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiffert T, Etzion Z, Bookchin RM, Lew VL. Effects of deoxygenation on active and passive Ca2+ transport and cytoplasmic Ca2+ buffering in normal human red cells. Journal of Physiology. 1993;464:529–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flatman P, Lew VL. Use of ionophore A23187 to measure and to control free and bound cytoplasmic Mg in intact red cells. Nature. 1977;267(5609):360–362. doi: 10.1038/267360a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muzyamba MC, Campbell EH, Gibson JS. Effect of intracellular magnesium and oxygen tension on K+-Cl− cotransport in normal and sickle human red cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2006;17(3-4):121–128. doi: 10.1159/000092073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lang K, Roll B, Myssina S, et al. Enhanced erythrocyte apoptosis in sickle cell anemia, thalassemia and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2002;12(5-6):365–372. doi: 10.1159/000067907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasin Z, Witting S, Palascak MB, Joiner CH, Rucknagel DL, Franco RS. Phosphatidylserine externalization in sickle red blood cells: associations with cell age, density, and hemoglobin F. Blood. 2003;102(1):365–370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Jong K, Kuypers FA. Sulphydryl modifications alter scramblase activity in murine sickle cell disease. British Journal of Haematology. 2006;133(4):427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joiner CH, Jiang M, Claussen WJ, Roszell NJ, Yasin Z, Franco RS. Dipyridamole inhibits sickling-induced cation fluxes in sickle red blood cells. Blood. 2001;97(12):3976–3983. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joiner CH. Deoxygenation-induced cation fluxes in sickle cells: II. Inhibition by stilbene disulfonates. Blood. 1990;76(1):212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfs JLN, Comfurius P, Bekers O, et al. Direct inhibition of phospholipid scrambling activity in erythrocytes by potassium ions. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2009;66(2):314–323. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8566-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gárdos G. The function of calcium in the potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1958;30(3):653–654. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson DR, Davis JL, Carraway KL. Calcium-promoted changes of the human erythrocyte membrane. Involvement of spectrin, transglutaminase, and a membrane-bound protease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1977;252(19):6617–6623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lang KS, Myssina S, Brand V, et al. Involvement of ceramide in hyperosmotic shock-induced death of erythrocytes. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2004;11(2):231–243. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiffert T, Spivak JL, Lew VL. Magnitude of calcium influx required to induce dehydration of normal human red cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1988;943(2):157–165. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bennekou P, Christophersen P. Ion channels. In: Bernhardt I, Ellory JC, editors. Red Cell Membrane in Health and Disease. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2003. pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strömqvist M, Berglund Å, Shanbhag VP, Backman L. Influence of calmodulin on the human red cell membrane skeleton. Biochemistry. 1988;27(4):1104–1110. doi: 10.1021/bi00404a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Z, Li S, Shi Q, Yan R, Liu G, Dai K. Calmodulin antagonists induce platelet apoptosis. Thrombosis Research. 2010;125(4):340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woon LA, Holland JW, Kable EPW, Roufogalis BD. Ca2+ sensitivity of phospholipid scrambling in human red cell ghosts. Cell Calcium. 1999;25(4):313–320. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stout JG, Zhou Q, Wiedmer T, Sims PJ. Change in conformation of plasma membrane phospholipid scramblase induced by occupancy of its Ca2+ binding site. Biochemistry. 1998;37(42):14860–14866. doi: 10.1021/bi9812930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Q, Zhao J, Wiedmer T, Sims PJ. Normal hemostasis but defective hematopoietic response to growth factors in mice deficient in phospholipid scramblase 1. Blood. 2002;99(11):4030–4038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flatman PW. The effect of buffer composition and deoxygenation on the concentration of ionized magnesium inside human red blood cells. Journal of Physiology. 1980;300:19–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]