After a multiyear planning process, the Vin McLoughlin Colloquium on the Epistemology of Improving Quality convened on 12–16 April 2010 at Cliveden, near London, England. This supplement offers an insight into the preparation for the meeting, the thinking that went into it and the implications of the work.

Preparing for the Colloquium

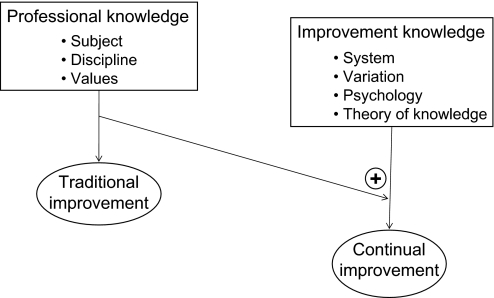

In 1982, W Edwards Deming suggested that complementary knowledge domains were important in improving quality.1 Taking that insight into healthcare, Batalden and Stoltz later suggested that traditional improvement was driven by intellectual disciplines that differed substantially from continual improvement2 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Linked knowledge systems for continual improvement.

This suggestion of different knowledge domains that might potentially complement traditional health professional knowledge and action has energised the learning and practice of healthcare leaders throughout the world.3–5

For several years preceding the Colloquium, colleagues met at the International Forums on Quality Improvement in Health Care to explore the diverse knowledge systems and controversies that underpin system-level, data-driven improvement research and practice. At the conclusion of the Paris meeting (2008), the idea of organising a more formal exploration of these different ways of knowing and their implications emerged in conversation.

International advisory planning group and inviting the right mix of people and disciplines

The initial group of colleagues convened at an international planning committee. The committee's charter was to (1) review and react to the proposed plan for the project and help steer development of the programme; (2) offer advice and counsel about relevant knowledge disciplines, possible participants and reactors; and (3) help connect the project to the communities of interest known better to the advisors than the project staff.

The committee agreed that each Colloquium participant should come prepared to discuss the following questions:

What types of knowledge their disciplines value, what methods those disciplines use to build that knowledge, and what are the ways by which they assess the validity, reliability, and generalisability of that knowledge?

How does this particular type of knowledge contribute, or might it contribute, to the improvement of health and healthcare quality, cost and safety?

What advice would they give to a young improver?

Planning a meeting structure that would offer deep listening, and critical thinking

A small ad hoc Colloquium leadership group finalised the list of invitees, noting the disciplines each invitee might represent. Prospective participants received a formal invitation that provided a statement of the purpose of the meeting. The organisers established personal connections with each prospective participant, which allowed for clarification of the meeting's aims and methods.

The invitation asked each participant to submit an abstract of the ideas they were planning to present in the meeting. Based on these abstracts, the organisers developed a general structure for the sessions that would permit concurrent small groups to consider a set of themes that were seen as worth pursuing (box 1). Each group was made up of diverse participants and disciplines; the organisers suggested an order for the presentations-cum-conversations relevant to the theme of each session.

Box 1. Premeeting clustering of themes and possible questions for initial small group meetings.

-

The knowledge that can inform the improvement of healthcare: its development and any tensions.

Possible questions for discussion include:

What knowledge is needed to improve healthcare and what are their vocabularies?

What is the role of ‘bio-medical’ knowledge? What affinities and tensions live between ‘bio-medical’ and other domains of ‘improvement knowledge?’

-

The ways that knowledge systems contribute to taking action for (limiting?) the improvement of healthcare.

Possible questions for discussion include:

What is involved in incorporating evidence into reliable practice?

What methods and approaches do different knowledge systems bring to designing and taking action? To measurement?

What role do ‘knowledge boundaries’ play?

How best to consider ‘context?’

How best to achieve ‘effective execution?’

-

The engagement of clinicians and others in the improvement of healthcare.

Possible questions for discussion include:

How best to teach this?

What relationships between teacher and student might be helpful?

What kinds of career paths?

What programmes might make sense?

-

The knowledge that underpins the evaluation of efforts to improve healthcare and their further development.

Possible questions for discussion include:

How best to evaluate/assess and learn from interventions?

How best to create helpful models?

How best to uncover assumptions, principles at work?

How best to understand the limits (boundaries?) of various evaluative methods?

The leadership group decided that the Colloquium should last a full 5 days in order to allow for deep exploration and iterative reframing of the issues in the context of others presented. Above all, the group wanted the meeting to be highly interactive and generative of helpful ideas and questions, as well as transformative for the perceptions and attitudes of participants. They arranged the programme so that every invitee would have the opportunity to present and (rare for events like this) open up their thinking in relation to the purpose of the meeting in a multidisciplinary small group. The pace of the meeting was designed to allow careful listening and promote active dialogue among participants.

Meeting and work that emerged from it

The Colloquium got under way with all participants' presentations being heard and discussed in their small groups on the first and second days. Once the conversations had taken place about the given themes in small groups, the entire group assembled to share the highlights of those conversations. To facilitate recall, recorders posted notes summarising those highlights. In each large group session, two participants were invited to share their reflections on what they had heard in the presentations from the small groups. This iterative processing of the work of individual participants, the small group conversations and the large group reflections allowed items to emerge that seemed to warrant further exploration.

On day 3, the work of the Colloquium was reframed around the extensive list of themes that had emerged during the first 2 days (box 2).

Box 2. Emergent themes worth further exploration and development.

Intervention (knowledge for; methods; multilevels; system interventions)

Generalisability*

How to evaluate—multiple (plural) evaluation methods*

Understanding variation, enumerative and analytic statistical thinking*

Pedagogy (development, curriculum)*

Theories (theory building, improving the theory of change, changing)*

Collaboratives

Integrating ‘clinical science’+‘social change/learning’+‘dramatic improvement of value’*

Implementation/adaptation*

Comparative effectiveness*

Power/engaging key stakeholders

Context and its role, measurement

How different disciplines can work, learn together/tribalism*

Faculty development

Innovation

Participants were invited to self-assemble into preference groups of two to four, each focused around a theme of interest. The themes that were selected from the list are denoted by an asterisk in box 2. Each small preference group was invited to pay particular attention to the current situation in healthcare, focusing especially on: the need for change; the need to improve the quality, safety and value of healthcare in their home countries; the desired situation and actors; setting high performance expectations; and the steps that might be needed to get from the current to the desired situation.

The organisers encouraged participants in the preference groups to consider their personal notes, presentations in the initial assigned small groups, comments made in the large groups and ideas captured on the presentation notes; in particular, they urged participants to characterise the current situation comprehensively. The organisers also invited preference group members to specify what would be necessary in the desired situation to integrate these ideas fully into the daily work routines of healthcare, such that improving care becomes part of the expected and usual daily work of delivering care. Finally, the organisers invited participants to be clear enough in their thinking that others could see and understand their reasoning, and could independently assess the likelihood that their recommendations would produce the desired changes.

After working together for a half-day, each of the nine preference groups offered a ‘rapid presentation’ to the large group for all to learn and share their thinking. A quick query in the large group about whether these actions and directions would get us where we want to go, and what needed to be clearer, allowed the entire group to absorb and comment on what they had heard in the rapid presentations. The preference groups then went back to work, preparing more organised short presentations for the opening of the final day. The aim of this segment of the Colloquium was to ‘rehearse’ the actions, stakeholders and possibilities for partnerships that might catalyse further work on the identified themes.

On the fifth day, the focus moved from strategies to tactics in a further effort to consider, imagine and rehearse the next steps. The aim was to give the participants time to consider possible actions they might personally take, develop further or foster. At this point, several other people who had been unable to attend the entire Colloquium but who were interested in taking action joined the large group, and some of the small preference groups. In these exercises, the groups focused on raising probing questions, figuring out how to make something important happen and foster the learning that might be needed. The organisers invited the small groups to put the big specific tasks that might offer leverage in some temporal order, and identify possible opportunities, partners, offers and commitments that seemed worth pursuing.

On the fourth evening of the meeting, the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajokull erupted, with unanticipated positive consequences for the work and the participants of the Colloquium. Participants with urgent postColloquium duties who were trying to make rapid departing plans were notified that no flights were available, and all routine departures were delayed. The effect of this unexpected and enforced ‘pause’ at the end of the Colloquium kept many of the participants together in conversation for several additional days—deepening the conversations and interactions of the preceding week. In retrospect, this accident of nature suggests that exploratory professional meetings might consider including some form of ‘additional time to ponder together’ after the formal meeting ends.

To summarise, the Colloquium was designed to open new questions, achieve new insights, make new connections and foster new relationships. It appears to have done all of those things. Illustrative of the transformative nature of the meeting was the closing comment by Steve Goodman, a well-respected physician-scholar and leading clinical trialist:

The notion of a ‘treatment’ as a ‘social change’… interferes with the [biomedical researcher's] understanding of what a safety intervention is…. Many are not aware of the richness of this discipline… I was one of those… you don't ‘see’ the paradigm you are in…. Before, I tended to think [of this social discipline] as a lower level intellectual activity… I now… think this is one of the big things… far more complex than many of the things I've given my attention to….

This supplement contains a variety of articles based on the thinking, the questions, and the dialogue that took place at the meeting. Some are drawn directly from the prework of participants, some from small group interaction and feedback, and some from the preference groups that came together around specified themes. Others are direct outgrowths of the work of the individual participants and their collaborators, and are the product of subsequent (post-Colloquium) reflection on the important themes of the week. Taken together, they offer an introduction to the remarkable variety of knowledge systems that are potentially helpful to those seeking to improve the quality, safety and value of healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The meeting was made possible by the work of the International Planning Committee (R Amalberti (FR), B Bergman (SE), P Bate (UK), D Berwick, (US), F Davidoff (US), V McLoughlin (UK) and P Batalden (US)) and by the Leadership Group (D Webb (UK), P Bate (UK) and P Batalden (US)). The authors wish to express their appreciation to F Davidoff for his helpful assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Both the meeting and this supplement benefited from the financial and professional staff support of The Health Foundation, an independent UK charity working to inspire improvement in the quality of healthcare. The untimely death of V McLoughlin prevented her from attending this meeting, which she so helpfully planned and fostered. The Colloquium is named in memory of her work.

Footnotes

V McLoughlin died on November 29, 2009.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Deming WE. Out of the Crisis. Boston: MIT Press, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batalden PB, Stoltz PK. A framework for the continual improvement of health care: building and applying professional and improvement knowledge to test changes in daily work. Jt Comm J Qual Improv 1993;19:425–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.http://www.ihi.org

- 4.Crump B. Should we use large scale healthcare interventions without clear evidence that benefits outweigh costs and harms? Yes. BMJ 2008;336:1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landefeld CS, Shojania KG, Auerbach AD. Should we use large scale healthcare interventions without clear evidence that benefits outweigh costs and harms? No. BMJ 2008;336:1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]