Abstract

We recently described a coreceptor switch in rapid progressor (RP) R5 simian-human immunodeficiency virus SF162P3N (SHIVSF162P3N)-infected rhesus macaques that had high virus replication and undetectable or weak and transient antiviral antibody response (S. H. Ho et al., J. Virol. 81:8621-8633, 2007; S. H. Ho, N. Trunova, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, and C. Cheng-Mayer, J. Virol. 82:5653-5656, 2008; and W. Ren et al., J. Virol. 84:340-351, 2010). The lack of antibody selective pressure, together with the observation that the emerging X4 variants were neutralization sensitive, suggested that the absence or weakening of the virus-specific humoral immune response could be an environmental factor fostering coreceptor switching in vivo. To test this possibility, we treated four macaques with 50 mg/kg of body weight of the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab every 2 to 3 weeks starting from the week prior to intravenous infection with SHIVSF162P3N for a total of six infusions. Rituximab treatment successfully depleted peripheral and lymphoid CD20+ cells for up to 25 weeks according to flow cytometry and immunohistochemical staining, with partial to full recovery in two of the four treated monkeys thereafter. Three of the four treated macaques failed to mount a detectable anti-SHIV antibody response, while the response was delayed in the remaining animal. The three seronegative macaques progressed to disease, but in none of them could the presence of X4 variants be demonstrated by V3 sequence and tropism analyses. Furthermore, viruses did not evolve early in these diseased macaques to be more soluble CD4 sensitive. These results demonstrate that the absence or diminution of humoral immune responses by itself is insufficient to drive the R5-to-X4 switch and the neutralization susceptibility of the evolving viruses.

The early events of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) entry in the target cells are characterized by the binding of the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 surface subunit with the cell receptor CD4, which allows gp120 to interact with one of two chemokine receptors, CCR5 (R5) or CXCR4 (X4) (3, 14). This interaction triggers subsequent conformational changes in the gp41 transmembrane subunit to promote the fusion of the viral and target cell membranes (18). Viruses that use R5 dominate in the early stages of HIV-1 infection. However, in about 50% of treatment-naïve subtype B HIV-1-infected patients, strains that use X4 emerge late in infection, overtaking the R5 viruses as the predominant virus in some cases (12, 26, 39). The viral determinant(s) of the phenotypic change from R5 to X4 maps largely to the V3 loop (10, 25, 41), requiring only a few amino acid substitutions in this region of the envelope gp120 to expand or alter coreceptor preference (9, 15, 19, 42). Given the minimal requirement for sequence change to confer the ability to use CXCR4, the high levels of virus replication and associated error rate (11), and the selective advantage of expanded target cell populations in vivo (4, 5), it is paradoxical that the switch from R5 to X4 virus does not occur more rapidly and frequently in HIV-1 infected individuals. Among the factors that have been proposed to favor CXCR4-using virus evolution and emergence are high viral replication and mutation rates that could give rise to X4 variants by chance, limitation in the availability of target CD4+ CCR5+ T cells, and the demise of immune selective pressures that control the expansion of newly evolving viral strains (33, 37). Because the emergence of X4 virus is strongly associated with a dramatic decline in CD4+ T-cell count and with a rapid progression to disease (13, 26), as well as concerns that drugs now in clinical development that target the CCR5 chemokine receptor could facilitate the emergence of X4 viral strains and exacerbate disease, there is an increasing need to improve our understanding of the selection pressures that favor CCR5-to-CXCR4 switching in vivo.

Recently, we identified and described cases of coreceptor switching in rhesus macaques (RM) infected with R5 simian-human immunodeficiency virus SF162P3N (SHIVSF162P3N) (23, 24, 38). The infected macaques in which the X4-using variants evolved all were rapid progressor (RP) animals, with high levels of viremia and the transient or undetectable development of antiviral antibody response. Moreover, the characterization of the emerging X4 viruses revealed that, similarly to what has been described for HIV-1-infected humans (7), the X4 variants were more sensitive to antibody neutralization than the inoculating or coexisting R5 viruses (23, 38, 43). These findings lend support to the notion that the humoral immune response plays a major role in suppressing the evolution and expansion of X4 viruses. Diminishing or blunting the development of virus-specific antibody response during R5 SHIVSF162P3N infection, therefore, may increase the chances of R5-to-X4 evolution and emergence. Accordingly, we treated rhesus macaques with rituximab, a monoclonal antibody (MAb) able to induce the depletion of CD20-expressing antibody-producing B cells prior to challenge with SHIVSF162P3N and monitored for coreceptor switching. We also examined the neutralization sensitivity of viruses in the B-cell-depleted animals to gain further insights into envelope glycoprotein evolution in the absence of antibody selective pressure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal infection.

The animals used were adult Indian rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) individually housed at the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC) in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at TNPRC. Animals were confirmed to be serologically negative for simian type D retrovirus, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), and simian T-cell lymphotropic virus at the time the study was initiated. Intravenous inoculations were carried out with 10,000 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of R5 SHIVSF162P3N. Whole heparinized blood and inguinal lymph node (LN) were sampled at designated intervals. Plasma viremia was quantified by branched DNA analysis (Siemens Medical Solution Diagnostic Clinical Lab, Emeryville, CA), and absolute CD4+, CD8+, and CD20+ cell counts were monitored by TruCount (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA). Animals with clinical signs of AIDS were euthanized by the intravenous administration of ketamine-HCl followed by an overdose of sodium pentobarbital. Additional lymphoid tissues were collected by surgery during the primary (3 or 6 weeks postinfection [wpi]) and chronic (12 wpi) stages of infection and at the time of euthanasia.

Cells.

Rhesus peripheral blood mononuclear cells (RhPBMCs) from naïve macaques were obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient purification followed by stimulation with 5 μg/ml staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 20 U/ml of interleukin-2 (IL-2; Novartis, Emeryville, CA). TZM-bl cells expressing CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4 (45) and containing integrated reporter genes for firefly luciferase and β-galactosidase under the control of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and l-glutamine. U87 indicator cell lines stably expressing CD4 and one of the chemokine receptors (17) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics, 1 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 300 μg/ml G418 (Geneticin; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Treatment with rituximab.

Four rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were infused intravenously (50 mg/kg of body weight) with rituximab (a gift from Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA), a human-mouse chimeric monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that induces naïve and memory B-cell depletion by Fc receptor-mediated antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity mechanisms (44). The first infusion occurred 1 week prior to intravenous inoculation with R5 SHIVSF162P3N. Infusions were repeated at 1, 4, 7, 10, and 13 wpi, for a total of six treatments.

Flow cytometry.

The percentage of CD4+ T cells in lymph node and intestinal specimens was analyzed by flow cytometry using CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD4-phycoerythrin (PE), and CD8-peridinin chlorophyll A protein (PerCP). The percentage of CD20+ T cells in blood and longitudinal inguinal lymph node biopsy specimens obtained at −2, 1, 3, 6 or 7, 10, and 18 wpi was determined using two different clones of CD20-FITC antibodies (L27 and B9E9). Except for CD3-FITC (BioSource, Camarillo, CA) and B9E9 (Beckman Coulter Inc., Miami, FL), all antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA).

Immunohistochemistry for CD20 and CD35.

To confirm flow cytometry data, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of CD20 expression in B cells and CD35 expression in germinal centers was carried out on lymph node samples collected at chronic infection (12 wpi) and at the time of necropsy due to AIDS or the end of the 68-week study period. Briefly, lymph node sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded ethanol to Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus Tween 20, with the blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity by incubation in 3% H2O2 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Antigen retrieval was accomplished by microwave heating sections at 95°C for 20 min in citrate buffer (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), followed by 20 min of cooling for CD20 and by proteinase K (Dako) treatment for 5 min at room temperature for CD35 and Dako protein block for 10 min. The blocked sections were incubated with anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (clone L26; IgG2a; 1:175 dilution; Dako) or with anti-CD35 monoclonal antibody (clone E11; IgG1; 1:100 dilution; LabVision, Fremont, CA) overnight at 4°C and then reacted with biotinylated secondary horse anti-mouse antibody (HAM-b; 1:200 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min. Sections were detected using an avidin-biotin peroxidase complex technique, ABC standard for CD20, or ABC elite for CD35 (Vector Laboratories), with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen (Dako). Slides were dehydrated through alcohol and xylene, counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin, and coverslipped using mounting medium (Richard-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI).

Analysis of anti-SHIV antibody response.

Titers of anti-SHIV binding antibodies in plasma were determined using the commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit HIV-1/HIV-2 plus 0 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Bio-Rad, Richmond, WA). SHIV-specific antibody responses also were examined using the strip immunoblot assay in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Immunetics, Boston, MA).

DNA extraction and sequencing.

Proviral DNA was extracted from 3 × 106 PBMC or lymph node cells isolated at the time of necropsy with a DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The V1 to V5 region of gp120 was amplified by using Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen) with primers ED5 and ED12 or ES7 and ES8 as previously described (16). PCR products were cloned with the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions, followed by the direct automated sequencing of cloned gp120 amplicons (SeqWright; Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX). Nucleotide sequences were aligned using the CLUSTALX 1.81 program and further adjusted manually.

Virus isolation and determination of coreceptor usage.

Viruses present in the B-cell-depleted animals at acute stage (2 wpi), chronic stage (12 wpi), and at the time of necropsy were recovered by the coculturing of PBMCs with SEB-stimulated PBMCs from naïve macaques. The p27gag antigen content of the recovered virus was quantified according to manufacturer's instructions (Beckman Coulter Inc., Miami, FL). The coreceptor usage of the recovered viruses was determined by blocking experiments in TZM-bl cells with CCR5 (TAK779) or CXCR4 (AMD3100) inhibitors and by the infection of U87.CD4 indicator cell lines. Briefly, for the blocking experiments, 7 × 103 cells per well of a 96-well plate were inoculated, in triplicate, with 1 ng p27gag antigen equivalent of the indicated SHIVs in the absence or presence of the coreceptor antagonists. The cells were lysed after 48 h of incubation at 37°C and processed for β-galactosidase activity according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The percentage of blocking was determined by calculating the amount of β-galactosidase activity in the presence of inhibitor relative to that in the absence of inhibitor. For the infection of U87.CD4.CCR5 or U87.CD4.CXCR4 cells with replication-competent SHIVs, 104 cells in each well of a 12-well plate were infected with 2 ng p27gag antigen equivalent of the indicated virus for 3 h at 37°C. Infected cells then were washed three times and cultured in 2 ml media for 7 to 10 days at 37°C, with supernatants collected every 2 to 3 days for p27gag antigen content quantification.

Neutralization assay.

Virus neutralization was assessed using TZM-bl cells in 96-well plates. Briefly, equal volumes (50 μl) of SHIV (1 ng p27gag equivalent) and serial dilutions of soluble CD4 (sCD4; PRO542; Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY) or sera from an SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaque were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then added to cells, in duplicate wells, for an additional 2 h at 37°C. A 100-μl aliquot of medium then was added to each well, and the virus-serum cultures were maintained for 48 h. Control cultures received virus in the absence of antibodies. At the end of the culture period, the cells were lysed and processed for β-galactosidase activity. A neutralization curve was generated by plotting the percentage of neutralization versus sCD4 concentration or serum dilution, and 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) were determined using Prism 4 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis.

SHIV replication through 28 wpi was transformed into areas under the curve (AUCs) and compared using Wilcox rank sum analysis. The survival rate comparison was based on Kaplan-Meier analysis.

RESULTS

Rituximab successfully depleted B cells in blood and tissues of SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques.

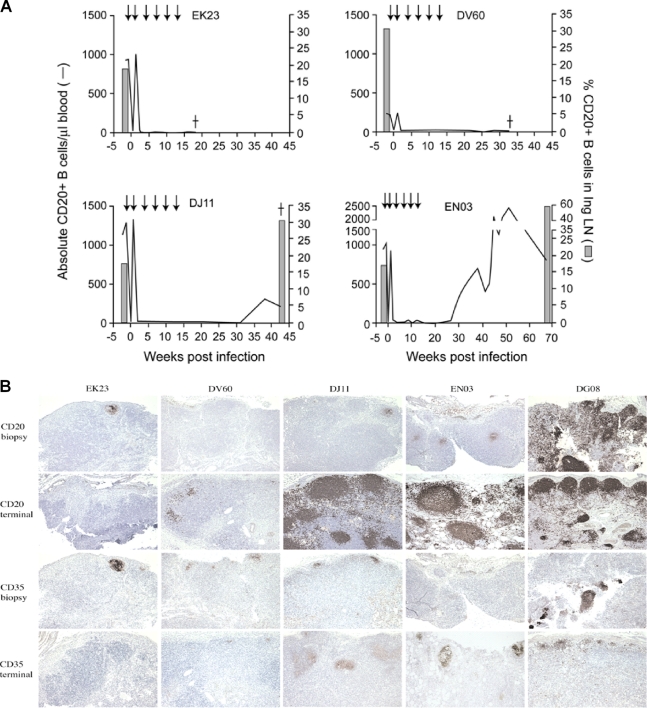

To assess the effect of B-cell depletion in R5 SHIVSF162P3N infection and coreceptor switching, four rhesus macaques (RM) were infused with 50 mg/kg of the anti-CD20 MAb rituximab the week before and at 1, 4, 7, 10, and 13 weeks after intravenous viral challenge. The rapid elimination of circulating CD20+ cells was seen 1 week after the first MAb treatment, a time corresponding to the time of virus inoculation, but rebounded close to pretreatment levels the week following (Fig. 1A). With the second infusion of rituximab, peripheral CD20+ cells again were depleted, and this depletion persisted in macaques EK23 and DV60 up to the time of necropsy (18 and 32 wpi, respectively). The reconstitution of circulating CD20+ cells, however, was seen in macaques EN03 and DJ11 at ∼30 wpi, 17 weeks after the last infusion of rituximab. The degree of peripheral CD20+ B-cell repopulation was modest in DJ11 but robust in EN03, reaching levels that exceeded pretreatment levels by 2-fold in this macaque at 50 wpi but returning close to baseline level at the end of the study period (68 wpi). Consistently with findings for blood, the flow-cytometric analysis of inguinal lymph node cells collected during and immediately following the period of anti-CD20 antibody treatment (1, 3, 6, 7, 10, and 18 wpi) revealed profound CD20+ B-cell depletion, with reconstitution above pretreatment levels only in macaques DJ11 and EN03 when examined at the time of necropsy for the former (43 wpi) and at the end of the study period for the latter (68 wpi).

FIG. 1.

Effect of rituximab treatment on CD20+ B cells in R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques. (A) B-cell concentration in peripheral blood and inguinal lymph node (Ing LN) over time. An arrow indicates the time of anti-CD20 MAb infusions, and a dagger indicates the time of death due to AIDS. (B) Immunohistochemistry for CD20 and CD35 in mesenteric lymph nodes. Sections of LN samples collected at the chronic stage (12 wpi; biopsy specimen), at the terminal disease stage for macaques EK23 (18 wpi), DV60 (32 wpi), and DJ11 (43 wpi), and at the end of the study period for EN03 (68 wpi) were stained for CD20- and CD35-expressing cells as described in the text, with the staining of corresponding sections from an R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected RP (DG08) in parallel for comparison.

Immunohistochemical staining largely confirmed flow cytometry data, showing the marked loss of CD20+ B cells in lymph nodes in rituximab-treated (EK23, DV60, DJ11, and EN03) RM compared to levels for untreated R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected rhesus macaque (DG08) (12 wpi biopsy specimen) (Fig. 1B). Depletion in lymph nodes was incomplete, however, in some cases (EK23, DJ11, and EN03), as has been previously reported (1, 21), with residual CD20+ cells within rare (EK23 and DJ11) to occasional (EN03) germinal centers. The analysis of terminal lymph node samples demonstrated a robust return of CD20+ cells within germinal centers in DJ11 and EN03, while EK23 and DV60 remain largely B-cell depleted. Complement receptor 1 (or CD35), expressed on B lymphocytes and follicular dendritic cells in germinal centers, also was decreased in CD20-depleted animals, with reappearance terminally in DJ11 and EN03. Collectively, the flow-cytometric analysis and staining of tissue cells revealed marked and sustained circulating and lymph node B-cell depletion during the course of infection in EK23 and DV60 but not in DJ11 and EN03, with the latter being the most incomplete.

Blunting of anti-SHIV antibody response following rituximab administration.

Treatment with rituximab effectively weakened the development of anti-SHIV humoral immune responses in the infected macaques. Three of the four treated animals failed to mount a detectable antibody response, as indicated by the lack of serum reactivity to SHIV antigens in an HIV-1/HIV-2 EIA (Table 1) and immunoblot assay (data not shown). The exception was macaque EN03, for which the anti-SHIV antibody response initially was weak (<1:100 serum dilution) but increased to high levels at 29 wpi (1:25,600), a time that coincided with a rebound in peripheral CD20+ B-cell count. The degree of antibody response in the rituximab-treated macaques, therefore, appears to correlate with the extent of B-cell recovery in the treated animals.

TABLE 1.

Measurement of anti-SHIV binding antibody endpoint titersa

| wpi | Endpoint titer for RM: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EK23 | DV60 | DJ11 | EN03 | |

| 0 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 |

| 1 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 |

| 2 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 |

| 3 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:5 |

| 4 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:5 |

| 5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:5 |

| 10 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:20 |

| 15 | <1:5 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:20 |

| 18 | <1:5b | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:100 |

| 21 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:100 | |

| 26 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:100 | |

| 29 | <1:5 | <1:5 | 1:25,600 | |

| 32 | <1:5b | <1:5 | 1:25,600 | |

| 43 | <1:5b | 1:102,400 | ||

| 68 | 1:102,400b | |||

SHIV-specific antibody titers in longitudinal plasma samples were measured using the commercially available ELISA kit HIV-1/HIV-2 plus O EIA. Endpoint titers are reported as the last 4-fold dilution above the cutoff of the assay.

Time of necropsy.

Disease progression in B-cell-depleted, R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques.

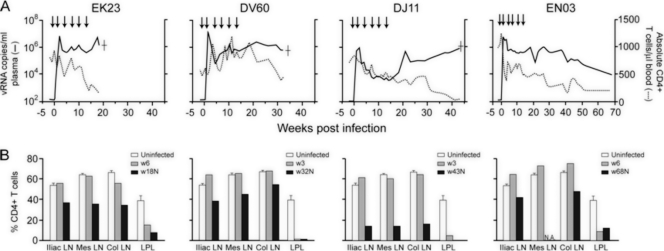

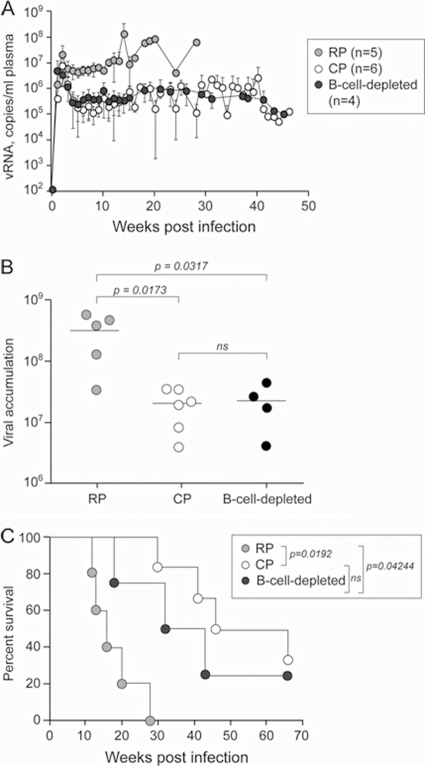

Peak plasma viremia of 106 to 107 RNA copies/ml was detected in three of the four rituximab-treated macaques by 2 wpi (EK23, DV60, and EN03) (Fig. 2A). Virus replication declined thereafter but rebounded by 10 wpi, reaching set points of 106 to 107 RNA copies/ml plasma for EK23 and DV60 and 105 to 106 RNA copies/ml plasma for EN03 at ∼25 wpi. Peak viremia was 1 log lower in DJ11 than in the other three macaques, and it dropped to levels of <104 RNA copies/ml plasma at 7 to 18 wpi. Virus replication rose, however, at 20 wpi to levels of >105 RNA copies/ml plasma and continued to increase thereafter. EK23, DV60, and DJ11, the three monkeys that were completely blocked from making anti-SHIV antibody responses, developed clinical signs consistent with AIDS and were euthanized at 18, 32, and 43 wpi, respectively. However, EN03, the macaque that did mount an anti-SHIV antibody response, remained clinically healthy during a 68-week study period.

FIG. 2.

Virologic and immunologic measurements in B-cell-depleted macaques. (A) Viral load and absolute CD4+ T-cell counts. Arrows indicate the time of rituximab infusions, and a dagger indicates the time of euthanasia due to AIDS. (B) Percentages of CD4+ T cells in the iliac (Ili), mesenteric (Mes), and colonic (Col) lymph nodes and lamina propria lymphocyte (LPL) from the jejunum during primary infection (3 to 6 wpi) and at the time of necropsy. Baseline values generated from two or three uninfected macaques are shown for reference. N.A., not available.

The four infected macaques displayed different patterns of peripheral CD4+ T-cell loss (Fig. 2B). A transient drop in circulating CD4+ T-cell count that accompanied acute infection and that is characteristic of pathogenic R5 SHIV infection was seen only in EN03. CD4+ T-cell recovery after acute infection was modest in this macaque, with a progressive and protracted decline that followed. In contrast, peripheral CD4+ T-cell numbers remained high (>500 cells/μl blood) and variable in EK23 and DV60 during peak and postacute infection but dropped rapidly toward the end stage disease. At the time of death, EK23 and DV60 had CD4 T-cell counts of 150 and 450 cells/μl blood, respectively. Despite the lower plasma viral load in DJ11, there was an early and progressive decline in peripheral CD4+ T-cell counts that became more precipitous at 30 wpi, with a CD4 T-lymphocyte count of only 62 cells/μl blood at the time of death. The percentages of CD4+ T cells in tissue compartments of the four infected macaques also were determined during primary (3 or 6 wpi) infection and at the time of death (Fig. 2B). As would be expected with pathogenic R5 SHIV infection, there was a significant loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes at effector sites such as the lamina propria (LP) of the gut in all four macaques during primary infection, with minimal depletion in peripheral lymph nodes. At the time of death, >90% of gut CD4+ T cells were depleted in EK23, DV60, and DJ11, while lymph node CD4+ T-cell loss was modest in EK23 and DV60 (20 to 40%) but more severe in DJ11 (∼75%), perhaps reflecting the longer period of virus replication in the latter animal. For EN03, >70% of CD4+ T cells were depleted in the gut at the end of the study period (68 wpi), with <20% loss in lymph nodes. The similarity in the tempo and extent of CD4+ T-cell depletion in the gut of the four monkeys contrasts with the more variable patterns of peripheral CD4+ T-cell loss. Moreover, the discordance between the peripheral blood CD4+ T-lymphocyte count and the plasma viral RNA levels seen in these animals was unexpected, suggesting that B-cell depletion has an effect in modifying the peripheral T-cell pool and function. Indeed, new data from patients and mouse models show that rituximab treatment can alter the subset composition, activation, function, and immune responses of CD4+ T cells (28). Regardless, a massive depletion (>95%) of peripheral blood and lymph node CD4+ T cells that would be expected in macaques harboring X4 viruses was not seen in the three B-cell-depleted macaques that developed AIDS.

No evidence of coreceptor switching in B-cell-depleted, R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques.

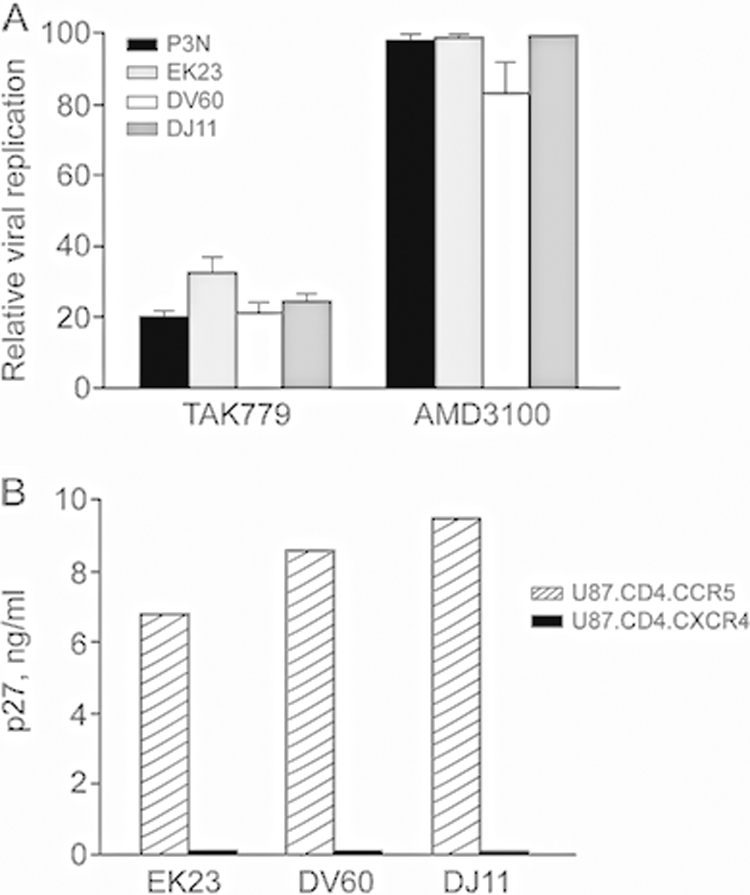

We recovered viruses from PBMCs of EK23, DV60, and DJ11 at the time of death and examined their coreceptor usage. Similarly to the parental SHIVSF162P3N isolate, the CCR5 inhibitor TAK779 efficiently blocked replication in TZM-bl cells of viruses recovered from EK23, DV60, and DJ11 (70 to 80% inhibition), while the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD-3100 was largely ineffective, with only low levels of virus inhibition seen for DV60 (∼15%) (Fig. 3A). The assessment of the ability of the viruses to infect U87.CD4 cells expressing either the CCR5 or CXCR4 coreceptor confirmed results of the blocking experiments, showing replication only in U87.CD4.CCR5 but not in U87.CD4.CXCR4 cells (Fig. 3B). Viruses at end-stage disease in EK23, DV60, and DJ11, therefore, remained CCR5 tropic.

FIG. 3.

Coreceptor usage of viruses recovered from PBMCs of EK23, DV60, and DJ11 at end-stage disease. CXCR4 and CCR5 usage was determined by blocking entry into TZM-bl cells with 1 μM CXCR4-(AMD3100)- or CCR5-(TAK779)-specific inhibitor (A) and the infection of U87.CD4.CCR5 and U87.CD4.CXCR4 cells (B). For TZM-bl cells, error bars indicate standard errors of data in triplicate wells, with the inoculating SHIVSF162P3N virus (P3N) serving as a control for CCR5 usage. For the infection of indicator cell lines, values represent p27 antigen production at day 7 postinfection. Results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments.

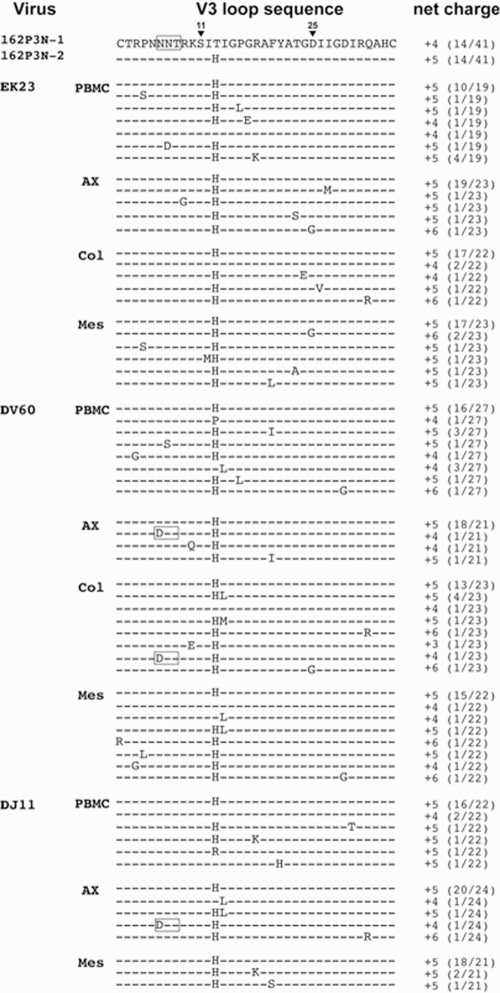

V3 loop sequence analysis showed that amino acid changes that are predictive of CXCR4 use, or that have been associated with coreceptor switching in R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected RP macaques, were absent in PBMCs as well as in lymph node compartments of macaques EK23 and DJ11 at the time of necropsy (Fig. 4). These include the insertion of basic amino acids upstream of the GPGR crown of the V3 loop and substitutions of the GPGR crown sequence or at position 11 in the V3 loop with basic amino acids. Variants with the loss of the N-terminal V3 loop glycan that we and others have reported to be associated with CXCR4 use (29, 36) could be detected in the axillary and colonic lymph nodes of macaque DV60 (1/21 and 1/23 envelope clones sequenced, respectively), as well as in the axillary lymph node of DJ11. Whether this V3 loop sequence change alone can confer CXCR4 usage to R5 SHIVSF162P3N remains to be determined, but the finding that >90% of CD4+ T cells are preserved in the colonic lymph node of DV60 despite the presence of these V3 variants argues against them being CXCR4 tropic in vivo. Thus, while three of four B-cell-depleted macaques progressed to disease within 45 wpi, overt signs of R5-to-X4 switch, which include severe peripheral lymph node CD4+ T-cell depletion, the emergence of viruses that use CXCR4 efficiently for entry, and signature envelope V3 sequence changes associated with coreceptor switching, were absent.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of V3 loop sequence of viruses in the inoculum SHIVSF162P3N and in PBMC and lymph nodes of EK23, DV60, and DJ11 at the time of death. Gaps are indicated as dots, dashes denote similarity in sequence, and the net-positive charge of this region was calculated and shown. Positions 11 and 25 within the V3 loop are designated, and the N-terminal glycan site is boxed. The numbers in parentheses represent the number of clones with the indicated V3 loop sequence/total number sequenced. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; Ax, axillary lymph node; Col, colonic lymph node; Mes, mesenteric lymph node.

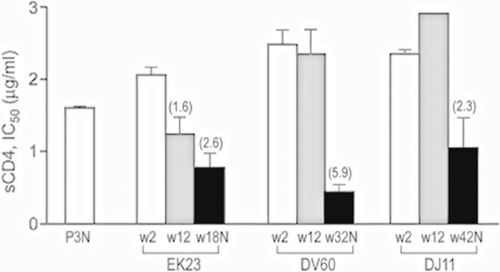

Viruses in B-cell-depleted infected macaques did not evolve early to be sCD4 sensitive.

Recent studies indicated that R5 viruses evolved early, at 4 to 12 wpi, and prior to the time of the switch in SHIVSF162P3N-infected RP macaques to sCD4-sensitive status (47). Increased sensitivity to neutralization with sCD4 is suggestive of the increased exposure of the receptor binding site, which usually is protected in the structure of the unliganded gp120 to avoid recognition by potential neutralizing CD4 binding site antibodies (35, 46). To determine if, similarly to the RP macaques with coreceptor switching, viruses in the B-cell-depleted macaques that failed to mount a detectable virus-specific antibody response and progressed to disease also evolved early to be sCD4 sensitive, we recovered viruses from PBMCs of macaques EK23, DV60, and DJ11 during acute (2 wpi) and chronic (12 wpi) stages of infection. We tested the susceptibility of these viruses, as well as the end-stage-recovered viruses and the inoculating R5 SHIVSF162P3N, to neutralization with sCD4 (CD4-IgG2). Results showed that the acute viruses in all three macaques were highly resistant to sCD4 neutralization compared to the inoculating SHIVSF162P3N isolate. Chronic (wpi 12) viruses from DV60 and DJ11 remained resistant, while those in macaque EK23 showed a <2-fold increase in sensitivity compared to that of the acute and inoculating viruses. Viruses recovered from all three macaques at end-stage disease, however, were more sensitive to sCD4 neutralization than the acute, chronic, and inoculating viruses, with those from DV60 being the most sensitive (Fig. 5). Thus, the absence of antibody selection pressure in the B-cell-depleted macaques was not sufficient to induce viruses to evolve early to be more sCD4 sensitive.

FIG. 5.

sCD4 sensitivity of acute, chronic, and end-stage disease viruses in B-cell-depleted macaques. The susceptibility of replication-competent viruses recovered from EK23, DV60, and DJ11 at 2 (acute) and 12 wpi (chronic) and the time of necropsy to sCD4 (CD4-IgG2) were determined and compared to that of the SHIVSF162P3N inoculum (P3N). Numbers above bars indicate the fold increase in sCD4 sensitivity compared to the level of the acute virus. Data are the means and standard deviations from at least two independent neutralization experiments.

Viral loads are significantly lower in B-cell-depleted macaques than in RP macaques infected with R5 SHIVSF162P3N.

Different effects of CD20+ cell depletion on SIV and X4 SHIV viral loads have been reported (20, 31, 40). High virus replication is a strong predictor for R5-to-X4 evolution in HIV-1-infected individuals (34). To better understand the basis for the lack of coreceptor switching in the B-cell-depleted animals, we compared the level of viremia and the rate of survival in the rituximab-treated SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques (n = 4) to that of animals from different studies that were classified as rapid (n = 5) or seropositive chronic (n = 6) progressors. Of the five RPs, three displayed coreceptor switching (23, 38). As shown in Fig. 6A, peak viremia overlapped for animals in the three groups, but the viral set point of the B-cell-depleted macaques was comparable to that of the chronic progressor (CP) macaques (∼106 copies/ml plasma) and was 1 log lower than that of the RPs. We also analyzed viral burden in the three groups of animals by calculating the area under the curve through 28 wpi, the longest time of survival for the RPs. Results showed that the cumulative viral load through 28 wpi was not significantly different between the B-cell-depleted and CP macaques but was significant between the B-cell-depleted monkeys and the RPs (P = 0.0317), with the former group of animals being lower (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the B-cell-depleted group survived longer than the RPs (P = 0.042). Thus, despite the fact that antibody selective pressure was absent in both the B-cell-depleted and rapidly progressing SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques, the viral load and survival rate of the B-cell-depleted macaques were more similar to those of SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques that mounted a virus-specific antibody response and had a normal course of disease progression.

FIG. 6.

Relationship between plasma RNA levels, survival, and antiviral antibody responses in SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques. Comparison of virus replication (A), plasma vRNA levels (AUCs) through 28 wpi (B), and survival rate (C) between R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques that are rapid progressors (RPs; n = 5), chronic progressors (CP; n = 6), and B-cell-depleted animals (n = 4). The mean plasma vRNA levels through 28 wpi (the longest time of survival for the RPs) were transformed into AUCs and compared using Wilcox rank sum analysis, and the survival rate comparison was based on Kaplan-Meier analysis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the effect of antibody immune selective pressure on HIV-1 coreceptor switching and neutralization sensitivity. We find that although the infusion of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab prior to and during the infection of rhesus macaques with R5 SHIVSF162P3N effectively depleted CD20+ B cells and blunted the development of virus-specific antibody responses, it did not favor the emergence of X4 using viral strains. Three of the four B-cell-depleted, SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques progressed to disease, but overt indicators of X4 presence, including dramatic peripheral blood and lymph node CD4+ T-cell loss, variants with CXCR4-associated signature V3 loop amino acid sequences, and the ability to use CXCR4 efficiently for entry, were not evident. We conclude, therefore, that while the absence or diminution of immune selective pressure in HIV-1-infected patients late in infection and in SHIVSF162P3N rapidly progressing macaques may be necessary to allow X4 variants that are neutralization sensitive to expand, it is not by itself sufficient to drive R5-to-X4 evolution. Significantly higher viral load was seen in the RP macaques than in the B-cell-depleted animals. As coreceptor switching was seen only in the former group of monkeys, these findings lend support to the notion that high levels of replication that result in more chances for viral mutations and the random generation of R5X4 and X4 using viruses is a prerequisite for coreceptor switch. In the absence of strong antibody selective pressure, as in the case of the RP macaques, these viruses are selected for because of expanded target cell population. Thus, similarly to the HIV-1 infection of humans (27, 34), high virus replication is a key predictor for R5-to-X4 evolution in SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques.

Interestingly, we find that viruses in the B-cell-depleted macaques, unlike those in RPs that had switched coreceptors, did not evolve early to become sCD4 sensitive. They also were not sensitive to neutralization with sera from SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques (data not shown). It has been well documented that HIV-1 exploits several mechanisms to escape from neutralizing antibody recognition in order to persist (6, 8, 45). Among these are a dense glycan coat and the repositioning of the loop structures on the gp120 that, although effective at shielding the targets for neutralizing antibodies on the surface of gp120 and the transmembrane gp41, impose fitness constraints on the virus (32). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that with the removal of antibody selective pressure, viruses would be selected or evolved rapidly to adopt a less constrained and open envelope conformation to improve fitness. However, this was not the case for the B-cell-depleted macaques. Viruses recovered from EK23, DV60, and DJ11 after acute infection (12 wpi) were not more sensitive to sCD4 or antibody neutralization than viruses in the inoculum or those present during acute infection (2 wpi). These observations suggest that the lack of neutralizing antibody selective pressure also is not sufficient to drive the virus to shed its glycan shield or to expose its receptor and coreceptor binding sites. Thus, other selective pressures, such as the adaptation to replicate in different T-cell subsets or in macrophages that express low levels of the CD4 receptor, may need to be considered to understand why viruses evolved early in RPs with coreceptor switching to be more sCD4 sensitive.

The role of humoral antibody response in viral control is controversial. Studies of SHIV and SIV infections showed that B cells are required to effectively control the levels of viral replication and the subsequent rate of disease progression in RMs (30, 31, 40) but not in the natural host infected with a neutralization-sensitive SIV strain (20). Although we find that the rank order of survival among the four B-cell-depleted R5 SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques tended to parallel the extent and duration of B-cell depletion as well as the capacity to make anti-SHIV antibodies, suggesting that humoral immune responses contribute to the control of disease, there were no statistically significant differences in viral replication, overall viral burden, or rate of survival between the B-cell-depleted macaques and chronic progressor macaques that mounted a virus-specific response. The small number of animals available for comparison in each of the two groups may have obscured subtle differences. Nonetheless, a comparison of the viral load and rate of progression to disease in the B-cell-depleted and rapid progressor macaques clearly shows that viral replication is significantly higher in the rapid progressors. Furthermore, RPs developed disease much more rapidly than the B-cell-depleted monkeys, despite the absence of antibody selective pressure in both. It is conceivable that the lack of seroconversion in the RPs is only one aspect of a more dramatic and broader destruction of the immune system functionality. Consistently with this notion is our finding of a more robust CD8+ T-cell response in the B-cell-depleted animal than in the RPs (data not shown). Since T-cell response has been shown to be involved in the control of viremia during both acute and chronic stages of infection (22) and is crucial for determining the disease outcome of HIV-1 infection (2), its presence in the B-cell-depleted macaques may account for the lower viremia and lower rate of disease progression of these animals compared to those of the RPs. A larger number of experimental animals will be needed to fully understand the role of anti-SHIV antibodies in SHIVSF162P3N pathogenesis.

In summary, we show that the depletion of B cells in a limited number of animals to ablate or diminish humoral selective pressure in vivo is insufficient to trigger coreceptor switching or increase the neutralization sensitivity of the evolving virus. However, a decline in virus-specific antibody response in HIV-1-infected individuals who have developed neutralizing antibodies is likely to be required for the expansion of X4 viruses that generally are more neutralization sensitive, explaining the late appearance of these variants in HIV-1-infected patients, when the immune system collapses, and in R5-SHIVSF162P3N-infected macaques that failed to mount a detectable antibody response. Thus, in contrast to high viral replication that generates the mutations and conditions favorable for coreceptor switching, neutralizing antibody selective pressure is an obstacle for tropism switch in vivo. Further studies using the simian model of coreceptor switching should provide additional insights into the mechanisms and selective forces for R5-to-X4 evolution in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to William Olsen for PRO 542 (Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY) and Wendy Chen for help with the graphics. The following were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: the TZM-bl (catalog no. 8129 from John C. Kappes, Xiaoyun Wu, and Tranzyme, Inc.) and U87.CD4 indicator cell lines (catalog no. 4035 and 4036 from HongKui Deng and Dan R. Littman) and reagents TAK779 (catalog no. 4983 from Takeda Chemical Industries, Ltd.) and AMD3100 (catalog no. 8128 from AnorMed, Inc.).

The work was supported by NIH grants RO1AI46980 and R37AI41945. Additional support was provided by Tulane National Primate Research Center Base grant RR00164.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahuja, A., et al. 2007. Depletion of B cells in murine lupus: efficacy and resistance. J. Immunol. 179:3351-3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appay, V., D. C. Douek, and D. A. Price. 2008. CD8+ T-cell efficacy in vaccination and disease. Nat. Med. 14:623-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger, E. A., P. M. Murphy, and J. M. Farber. 1999. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17:657-700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkowitz, R. D., et al. 1998. CCR5- and CXCR4-utilizing strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 exhibit differential tropism and pathogenesis in vivo. J. Virol. 72:10108-10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaak, H., et al. 2000. In vivo HIV-1 infection of CD45RA(+)CD4(+) T cells is established primarily by syncytium-inducing variants and correlates with the rate of CD4(+) T-cell decline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:1269-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bou-Habib, D. C., et al. 1994. Cryptic nature of envelope V3 region epitopes protects primary monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from antibody neutralization. J. Virol. 68:6006-6013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunnik, E. M., L. Pisas, A. C. van Nuenen, and H. Schuitemaker. 2008. Autologous neutralizing humoral immunity and evolution of the viral envelope in the course of subtype B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 82:7932-7941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao, J., et al. 1997. Replication and neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 lacking the V1 and V2 variable loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 71:9808-9812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, J. Nishio, and S. Perryman. 1996. Mapping of independent V3 envelope determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 macrophage tropism and syncytium formation in lymphocytes. J. Virol. 70:9055-9059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocchi, F., et al. 1996. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-mediated blockade of infection. Nat. Med. 2:1244-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffin, J. M. 1995. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science 267:483-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor, R. I., K. E. Sheridan, D. Ceradini, S. Choe, and N. R. Landau. 1997. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Exp. Med. 185:621-628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daar, E. S., et al. 2007. Baseline HIV type 1 coreceptor tropism predicts disease progression. Clin. Infect. Dis. 45:643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalgleish, A. G., et al. 1984. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature 312:763-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Jong, J. J., A. De Ronde, W. Keulen, M. Tersmette, and J. Goudsmit. 1992. Minimal requirements for the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 domain to support the syncytium-inducing phenotype: analysis by single amino acid substitution. J. Virol. 66:6777-6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delwart, E. L., and C. J. Gordon. 1997. Tracking changes in HIV-1 envelope quasispecies using DNA heteroduplex analysis. Methods 12:348-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng, H., et al. 1996. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doms, R. W., and J. P. Moore. 2000. HIV-1 membrane fusion: targets of opportunity. J. Cell Biol. 151:F9-F14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fouchier, R. A., et al. 1992. Phenotype-associated sequence variation in the third variable domain of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 molecule. J. Virol. 66:3183-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaufin, T., et al. 2009. Effect of B-cell depletion on viral replication and clinical outcome of simian immunodeficiency virus infection in a natural host. J. Virol. 83:10347-10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gong, Q., et al. 2005. Importance of cellular microenvironment and circulatory dynamics in B cell immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 174:817-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goulder, P. J., and D. I. Watkins. 2008. Impact of MHC class I diversity on immune control of immunodeficiency virus replication. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:619-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho, S. H., et al. 2007. Coreceptor switch in R5-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Virol. 81:8621-8633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho, S. H., N. Trunova, A. Gettie, J. Blanchard, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 2008. Different mutational pathways to CXCR4 coreceptor switch of CCR5-using simian-human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 82:5653-5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang, S. S., T. J. Boyle, H. K. Lyerly, and B. R. Cullen. 1991. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as the primary determinant of cell tropism in HIV-1. Science 253:71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koot, M., et al. 1993. Prognostic value of HIV-1 syncytium-inducing phenotype for rate of CD4+ cell depletion and progression to AIDS. Ann. Intern. Med. 118:681-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koot, M., et al. 1999. Conversion rate towards a syncytium-inducing (SI) phenotype during different stages of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and prognostic value of SI phenotype for survival after AIDS diagnosis. J. Infect. Dis. 179:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lund, F. E., and T. D. Randall. 2010. Effector and regulatory B cells: modulators of CD4(+) T-cell immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:236-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malenbaum, S. E., et al. 2000. The N-terminal V3 loop glycan modulates the interaction of clade A and B human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelopes with CD4 and chemokine receptors. J. Virol. 74:11008-11016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mao, H., et al. 2005. CD8+ and CD20+ lymphocytes cooperate to control acute simian immunodeficiency virus/human immunodeficiency virus chimeric virus infections in rhesus monkeys: modulation by major histocompatibility complex genotype. J. Virol. 79:14887-14898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, C. J., et al. 2007. Antiviral antibodies are necessary for control of simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 81:5024-5035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore, J. P., and D. D. Ho. 1995. HIV-1 neutralization: the consequences of viral adaptation to growth on transformed T cells. AIDS 9(Suppl. A):S117-S136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore, J. P., S. G. Kitchen, P. Pugach, and J. A. Zack. 2004. The CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptors-central to understanding the transmission and pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 20:111-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moyle, G. J., et al. 2005. Epidemiology and predictive factors for chemokine receptor use in HIV-1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 191:866-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pantophlet, R., and D. R. Burton. 2006. GP120: target for neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 24:739-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polzer, S., M. T. Dittmar, H. Schmitz, and M. Schreiber. 2002. The N-linked glycan g15 within the V3 loop of the HIV-1 external glycoprotein gp120 affects coreceptor usage, cellular tropism, and neutralization. Virology 304:70-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Regoes, R. R., and S. Bonhoeffer. 2005. The HIV coreceptor switch: a population dynamical perspective. Trends Microbiol. 13:269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren, W., et al. 2010. Different tempo and anatomic location of dual-tropic and X4 virus emergence in a model of R5 simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 84:340-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scarlatti, G., et al. 1997. In vivo evolution of HIV-1 co-receptor usage and sensitivity to chemokine-mediated suppression. Nat. Med. 3:1259-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmitz, J. E., et al. 2003. Effect of humoral immune responses on controlling viremia during primary infection of rhesus monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 77:2165-2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shioda, T., J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1991. Macrophage and T cell-line tropisms of HIV-1 are determined by specific regions of the envelope gp120 gene. Nature 349:167-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shioda, T., J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1992. Small amino acid changes in the V3 hypervariable region of gp120 can affect the T-cell-line and macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:9434-9438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tasca, S., S. H. Ho, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 2008. R5X4 viruses are evolutionary, functional, and antigenic intermediates in the pathway of a simian-human immunodeficiency virus coreceptor switch. J. Virol. 82:7089-7099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor, R. P., and M. A. Lindorfer. 2008. Immunotherapeutic mechanisms of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 20:444-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei, X., et al. 2003. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature 422:307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyatt, R., et al. 1998. The antigenic structure of the HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature 393:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhuang, K., et al. 2010. Adaptation to use low levels of the CD4 receptor is an early event in the process of co-receptor switching in R5 SHIV-infected rapid progressors. Abstr. 17th Conf. Retrovir. Opportun. Infect., abstr. 272.