Abstract

This manuscript describes some of the early work on pyrethroid insecticides in the Casida laboratory and briefly reviews the development and application of immunochemical approaches for the detection of pyrethroid insecticides and their metabolites for monitoring environmental and human exposure. Multiple technologies can be combined to enhance the sensitivity and speed of immunochemical analysis. The pyrethroid assays are used to illustrate the use of some of these immunoreagents such as antibodies, competitive mimics, and novel binding agents such as phage-displayed peptides. We also illustrate reporters such as fluorescent dyes, chemiluminescent compounds, and luminescent lanthanide nanoparticles, as well as the application of magnetic separation, and automatic instrumental systems, biosensor and novel immunological technologies. These new technologies alone and in combination result in an improved ability to determine both if effective levels of pyrethroids are being used in the field as well as evaluate possible contamination.

Keywords: Pyrethroid insecticides, immunoassay, biosensors, monitoring

Introduction

Immunodiagnostics are well-suited to analysis of substances that are difficult to analyze with GLC or HPLC because of large molecular mass, thermal liability, low volatility or lack of a distinct chromophore. Thus these analytical technologies are complementary. Proteins expressed in recombinant crops are one example of such difficult targets. However, field portability, high sample throughput, and other problems also are well addressed by immunoassays. Antibodies in immunodiagnostics act as a receptor (detector) for the analyte of interest. Tight binding and thus high sensitivity of the resulting assays occurs through hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic bonding, electrostatic, and van der Waals forces (1). Lack of these interactions as well as steric constraints can yield exceptional specificity. Thus detection takes advantage of multiple physical and chemical properties not easily exploited by other instruments. The same immunochemical reagents can be formatted to give highly quantitative and extremely sensitive laboratory assays or formatted as qualitative or semi quantitative rapid field tests. The unique attributes of immunodiagnostics make them very attractive for pesticide analysis when large numbers of samples must be examined for a small number of compounds, when tests need to be run in the field or in remote laboratories, when automated fluidic devices must be used, or when particularly complex structures must be analyzed.

Immunodiagnostic technology is one of the few areas of pesticide science where John Casida has not had a major role. Yet, even here the Casida laboratory had a presence when they used the cyclodiene selective monoclonal antibody developed by Alex Karu to investigate the mechanism of action of tetramethylenedisulfotetramine (2). However at least indirectly, John Casida founded the immunodiagnostic field as well. In the pyrethroid area, the Wellman Hall basement was a Mecca in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Having scientists like Michael Elliott and Kenzo Ueda working on the chemistry of the pyrethroids and collaborating with Loretta Gaughan, Ella Kimmel and Izuru Yamamoto on the metabolism of the compounds was exceptionally exciting. The environment was made even more exciting by the fact that within the Casida laboratory we all knew the pyrethroids were destined to become major products, while most of the pesticide community thought that innovation in the pyrethroid area ended with the publications of Schechter, Green and LaForge on allethrin. The enthusiasm of Charles Abernathy and later Lien Jao and David Soderlund added to a relatively large group of people in the area at the very start of a new field. The discovery of Abernathy and Soderlund in the Casida laboratory that ester cleavage could be a major route of metabolism of pyrethroids with unhindered esters in both mammals and insects (3,4) led to the resulting ester cleavage products being used as biomarkers of pyrethroid exposure.

The pyrethroids were the examples used by Michael Elliot and Kenzo Ueda in their effort to teach me (BDH) a little chemistry. While at Berkeley it was exceptionally entertaining to watch the development of a new field from the sidelines. Thus, when I started a new laboratory at UC Riverside in 1975, I very much wanted to work in this area since pyrethroid chemistry was one of the few gems in my bag of tricks. By 1975 competing with industry on structure activity work certainly was out of the question and competing with the Casida laboratory on the metabolism and environmental chemistry of pyrethroids was beyond foolish.

Among several things that I worked on with Larry Gilbert as a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University was the evaluation of an immunoassay for insect juvenile hormone developed in Koji Nakanishi’s laboratory. The assay was wonderful, but only so long as it was run in buffer. I developed a plan to make a good immunoassay for juvenile hormone that would work in a complex matrix, and I started on this project as soon as I arrived as a faculty member at UC Riverside. I had just immunized rabbits with the synthetic hapten for juvenile hormone when my former postdoctoral mentor and I met for dinner. Larry pointed out that he had just started a new collaboration with a French group to develop an improved juvenile hormone immunoassay. My continuing the juvenile hormone immunoassay work seemed untenable. My laboratory would either develop a better juvenile hormone immunoassay and place me in an embarrassing situation with my postdoctoral mentor, or my laboratory would fail and have nothing to show. Since in my bag of tricks I could do pyrethroid synthesis, could do immunoassays, and for other reasons I had some skill with oxymercuration developed by Herbert Brown, I decided to combine these skills to make pyrethroid immunoassays. Pesticide immunoassay was a high risk undertaking with only limited work in the environmental field from the laboratory of C. D. Ercegovich and later Ralph Mumma at Pennsylvania State University. The first target was the pyrethroid insecticide allethrin based on the idea that allethrin and the natural pyrethrins presented difficult analytical problems because of their lack of stability on GLC, lack of halogen, phosphorous and nitrogen atoms for selective detection, and three chiral centers even in allethrin. It was also an attractive target because allethrin like the natural pyrethroids is most active as the 1R, 3R, 4’S isomer. T. Roy Fukuto in the division was just then advancing the concept in pesticide chemistry that chirality could be very important for biological activity. The hope was that success on these difficult light, air and water unstable chiral targets would demonstrate the power of the immunochemical approach. Thus the field of pesticide immunoassay in a way started in an effort to find a use for 4 rabbits that had already been injected with an antigen for an insect hormone and to find a niche to ply a trade that was slightly different than ongoing research in either the Casida or the Gilbert laboratory. The initial S-bioallethrin assay turned out to be very successful thanks to wonderful advice from Roy Fukuto and David Wustner and the enthusiastic collaboration of Keith D. Wing whose Ph.D. work started the field of pesticide immunoassay (5–7). The work was successful in another way in permitting me to continue my ties with Mike Elliott, Kenzo Ueda, John Casida and others working on pyrethroids, place Keith Wing in the Casida laboratory as a postdoctoral fellow, and later have Don Stoutamire join my laboratory after leaving Shell Chemical Company. Don in fact had worked with John Casida as an undergraduate in Wisconsin and later developed the key step in the chiral synthesis of esfenvalerate at Shell Modesto.

Our subsequent work on immunoassays led to the development of assays for genetically engineered organisms, pesticides, environmental contaminants, microbes, personal care products, terror agents, and many other targets. Of course as the importance of the modern pyrethroid insecticides grew, the importance of the immunochemical tools for their study expanded. For the last 35 years the pyrethroid insecticides and their metabolites have been important targets for immunoassay development in this and other laboratories.

Immunoassays of course are widely used in research and in medical diagnostics. As predicted in the early review by Hammock and Mumma (7), their uses have increased in environmental chemistry and particularly in pesticide analysis. As mentioned above the first pesticide immunoassays developed in this laboratory was the assay for S-bioallethrin which was able to distinguish the single most active optical and geometrical isomer out of a mixture of materials with three chiral centers. The assays cross react with t he natural chrysanthemic pyrethrins and could be used for crop breeding or to drive approaches in biotechnology to produce these valuable natural products. Pyrethroids are the synthetic mimics of the natural pyrethrins, and allethrin was the first successful member of the series produced to address insect vector problems during World War II. Years later the superb group led by Michael Elliott at the Rothamsted Experimental Station led to pyrethroid insecticides useful in field and row crop agriculture. This work was developed by many companies and the pyrethroids have emerged as the dominant insecticide class used worldwide. As pyrethroid use has expanded new immunoassays have been developed which are highly selective for individual pyrethroids, for subclasses of pyrethroids, and that are selective for metabolites and environmental degradation products which arise from a single pyrethroid or from groups of pyrethroids. Many of these assays can distinguish among geometrical and optical isomers. These selective assays have proven useful in the monitoring of human body fluids as well as the environment.

Here we briefly describe the development of immunoassays for small molecules. A key factor is that a mimic of the target pesticide must be attached to a protein carrier in order to raise antibodies. The mimic is referred to as a hapten and the conjugate as the antigen to which antibodies are raised. The type of immunoassay most commonly applied to the analysis of pesticides and other small molecules is a competitive immunoassay. Although very powerful this assay format reduces signal as the analyte concentration increases. Toward the end of the review we discuss biosensor development as such sensors have been applied to pyrethroids and other pesticides. Biosensors can be defined as devices resulting from the association of a sensitive biological element with a transducer which converts the biological signal into a measurable physical signal. The transducer is in close proximity to or is integrated with an analyte-selective interface (8). Immunosensors are a specialized type of biosensor which utilizes antibodies for detection. This approach to antibody-based sensors can provide continuous, in situ, rapid, and sensitive measurements based on conventional immunoassay techniques. Advances in these technologies permit the development of small molecule immunoassays which are non-competitive in that assay signal increases with the increase in analyte.

Development of immunoassays for measuring the residues of parent pyrethroid(s) in environmental samples

There are many reasons why the synthetic pyrethroid insecticides such as bifenthrin, cypermethrin, deltamethrin, fenpropathrin and permethrin are rapidly replacing other pesticides in both vector control and agriculture. Their mode of action (highly potent disruption of voltage-sensitive sodium channel function in insects), variable environmental persistence, and greater safety for farm workers and wildlife make them increasingly attractive as the cost of these complex molecules has dropped.

Many immunoassays have been developed that are highly selective for individual pyrethroids, for subclasses of pyrethroids, and for metabolites and environmental degradation products that arise from a single pyrethroid or from groups of pyrethroids. As shown in Table 1, these assays use monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies produced against specially designed and synthesized target mimics (9–20). Subgroup selective immunoassays have been developed for distinguishing Type I and Type II pyrethroids, following the preparation of group-specific mimics with/without the distinguishable alpha-cyano (−CN) group and with the phenoxybenzyl moiety (21–23). Additionally, a broad immunoassay was developed (24) for the total class of pyrethroid insecticides by using a mixture of mimics with/without −CN group and testing for the analysis of a panel of mixtures of type I and II pyrethroids that contain a phenoxybenzyl moiety. Polyclonal antibodies were used for this broad class-specific assay. Most immunoassays for pyrethroid detection used polyclonal rabbit antiserum because of the low costs, time savings in production and screening, and high titer antibody generation compared to monoclonal antibody production. These polyclonal immunoassays are highly selective for the target pyrethroid insecticide(s) of interest.

Table 1.

ELISAs developed to monitor environmental exposure to pyrethroid insecticide(s) and their metabolite(s).

| Target analyte | Format | Anti- body |

IC50c (µg/L) |

LODd (µg/L) IC10 or 20c |

Re- ference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allethrin | Indirect competitive ELISA | MAba | 46 | -e | 9 |

| Cyhalothrin | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAbb | 37.2 | 4.7 | 10 |

| Cypermethrin | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 13.5 | 1.3 | 11 |

| Deltamethrin | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 17.5 | 1.1 | 12 |

| Deltamethrin (isomerized) | Direct competitive ELISA | PAb | 1.5–4.2 | 0.2–0.7 | 13 |

| Deltamethrin | Direct competitive ELISA | MAb | 10 | 1.5 | 14 |

| Esfenvalerate | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 30 | 3 | 15 |

| Etofenprox | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 1.1 | ~8 | 16 |

| Etofenprox | Indirect competitive ELISA | MAb | 0.5 | ~1 | 16 |

| Fenpropathrin | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 20 | 2.5 | 17 |

| Flucythrinate | Indirect competitive ELISA | MAb | 33 | ~2 | 18 |

| cis/trans-Permethrin | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 2.5 | 0.3 | 19 |

| Pyrethroids including a chrysanthemic acid moiety | Competitive ELISA | MAb | 3.2 (allethrin) 7.1 (bioallethrin) 9.4 (pyrethrin) 2.8 (tetramethrin) |

1 (allethrin) | 20 |

| Type I pyrethroids including a phenoxybenzyl without alpha-cyanogroup | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 30 (permethrin) | 0.3 | 21 |

| Type II pyrethroids including alpha-cyanophenoxybenzyl moiety | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 78 (cypermethrin) | - | 22 |

| Type II pyrethroids | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 4.6 (cyphenothrin) 5.6 (fenpropathrin) 7.1 (deltamethrin) 10.7 (cypermethrin) 20.0 (flucythrinate) 28.2 (esfenvalerate) |

0.1 (cyphenothrin) |

23 |

| Types I and II pyrethroids including phenoxybenzyl moiety with/without CN group | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 20 (phenothrin, permethrin, deltamethrin, cypermethrin, and cyhalothrin) | 1.5 | 24 |

| 3-PBA-glycine (metabolite) | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 0.4 | 0.04 | 48 |

| S-Fenvalerate acid-glycine (metabolite) | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 0.4 | 0.03 | 48 |

| cis/trans-DCCA-glycine (metabolite) | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 1.2 | 0.2 | 49 |

| 3-PBAlc-glucuronide (metabolite) | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 1.8 | 0.3 | 50 |

| 3-PBA (metabolite) | Indirect competitive ELISA | PAb | 1.7 | 0.1 | 51 |

MAb, Monoclonal antibody.

PAb, Polyclonal antibody.

IC10, 20 or 50: Inhibition of 10, 20, or 50% by the target compound.

LOD, Limit of detection.

not mentioned.

The assays developed have been applied to various real sample matrixes. Table 2 summarizes the type of samples, the limit of quantitation (LOQs), recoveries, and the sample preparation methods. The overall LOQs were ranged from 0.1 to about 500 µg/L or µg/kg in the respective samples using simple clean-up methods (10–12, 14, 18, 19, 23–28, 59, 63). The LOQs are low enough to measure the pyrethroid in the matrix of interest. The average recoveries from the samples mostly ranged from 70–120 %, suggesting the immunoassays were acceptable screening tools. Sample extracts or aqueous samples were either directly measured by ELISA after dilution with buffer, or, if a very low LOQ was required, the sample was further purified by relatively simple solid-phase extraction, liquid-liquid, or immunoaffinity purification methods. Antibodies can also be used for immunoaffinity cleanup and concentration of samples as exemplified by an HPLC on-line clean-up method that used a pyrethroid class selective rabbit antiserum. This method provided a sensitive high-throughput analysis (29).

Table 2.

List of pyrethroid insecticides and their metabolites that have been analyzed by immunoassay.

| Target analyte | Sample | Limit of quantification (µg/L or µg/kg) |

Recovery (%) |

Sample preparation method |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioallethrin | Strawberry | -a | 144 | Extract- IAb/Florisil clean-up | 25 |

| Bioallethrin | Soil | - | >100 | Extract- IA/Florisil clean-up | 25 |

| Bioallethrin | House dust | - | 100 | Extract- IA/Florisil clean-up | 25 |

| Cyhalothrin | Tap/well/waste water | 100 | >80 | C18 SPEc | 10 |

| Cypermethrin | Tap water | 0.2 | 76–92 | C18 SPE | 11 |

| Cypermethrin | Lake/runoff waters | 2 | 68–129 | C18 SPE | 11 |

| Cypermethrin | White wine | 50 | 85–110 | Dilution | 26 |

| Cypermethrin | Orange oil | 500 | >65 | LLEd-silicaSPE | 27 |

| Deltamethrin | River water | 0.2 | 89–115 | C18 SPE | 12 |

| Deltamethrin | Fat milks | 20 | 92–148 | LLE | 28 |

| Deltamethrin | Water | 1 | >93 | Dilution | 63 |

| Deltamethrin | Soil | 500 | 88 | Extract-Dilution | 63 |

| Deltamethrin | Wheat grain | 13 | 81 | Extract-Dilution | 63 |

| Flucythrinate | River/pond water | 10 | >90 | Direct | 18 |

| Flucythrinate | Soil | 200 | >95 | Extract-Dilution | 18 |

| Flucythrinate | Apple/Tea | 300 | >95 | Extract-Dilution | 18 |

| Permethrin | River water | 0.01 | 76–110 | C18 SPE | 19 |

| Permethrin | White/red wines | 50 | 36–97 | Dilution | 26 |

| Permethrin | Lettuce/peach | 50 | 84–100 | Extract-Dilution | 26 |

| Permethrin | Apple/banana/onion | 70 | 82–122 | Extract-Dilution | 26 |

| Permethrin | Cucumber | 100 | 43–99 | Extract-Dilution | 26 |

| Permethrin | Grain | 75 | ~80 | Extract-Alumina clean-up | 14 |

| Permethrin | Meat | 50 | 62 | Extract-LLEalumina clean-up | 59 |

| 3-PBA (metabolite) | Urine | 1 | >76 | Mixed mode SPE | 58 |

| cis/trans-DCCA-glycine (metabolite) | Urine | 1 | 65–123 | C18 SPE | 53 |

not mentioned

IA, Immunoaffinity column.

SPE, Solid phase extraction.

LLE, Liquid-liquid extraction.

Development of immunoassays for measuring specific pyrethroid metabolites in human body fluids

As the use of pyrethroid insecticides increases, so do concerns about human health. Pyrethroid insecticides are classified as potential environmental endocrine disrupters that can interfere with or mimic natural hormones in the body. Other adverse effects are related to carcinogenicity (30, 31), immunotoxicity (32–34), neurodevelopmental disorders (35–37) and central nervous system abnormalities in infants (38, 39). The common sources of continuously repeated low level exposure to pyrethroid insecticides for the general population are thought to occur via residues in diet and in drinking water and via contact with air and dust containing residues after application in households. Persons such as farmers, pesticide applicators, and manufacturers may receive occupational overexposure via inhalation and dermal contact. Particular attention may be given to the health of more susceptible neonates, infants, young children, and women of childbearing age and pregnant women.

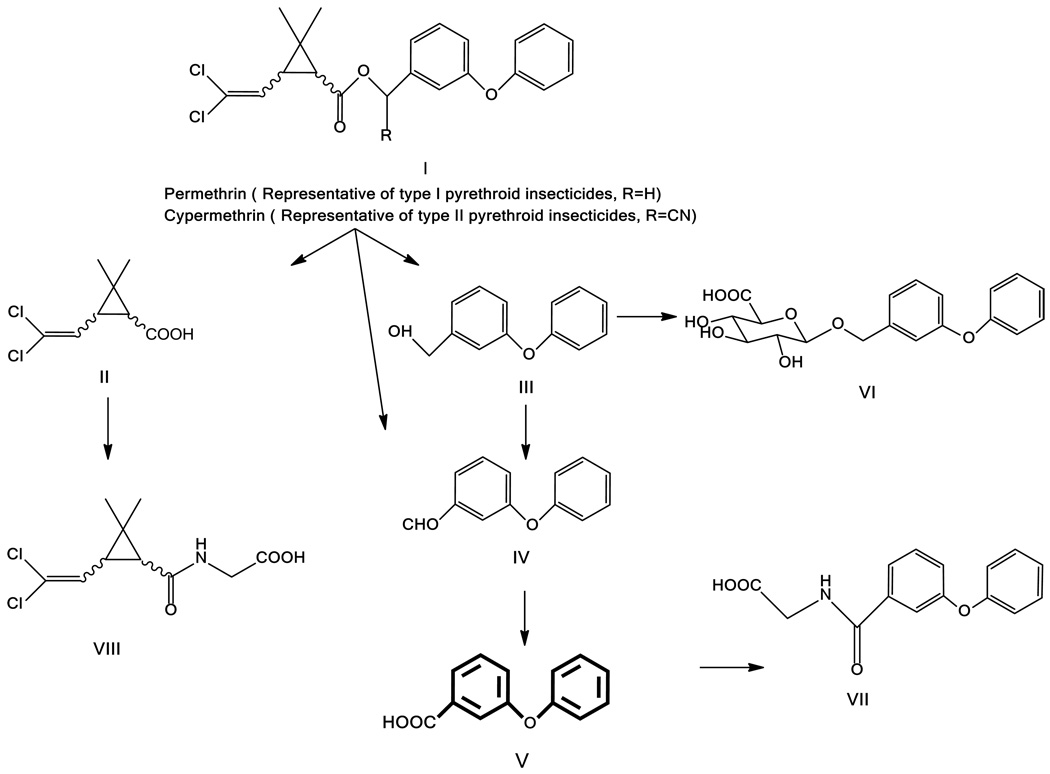

Because of the lack of environmental degradation due to factors such as sun, rain, and soil microbial activity, high concentrations of a large number of pesticides were found in house dust in the general population (40–42). As first demonstrated in the Casida research group (Figure 1), in mammals, the ester type of pyrethroids do not accumulate in tissues or persist in blood. They are quickly metabolized by enzymatic hydrolysis into the main polar metabolites cis/trans-3-(2,2-dichlorovinyl)-2,2-dimethylcyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (cis/trans-DCCA, II) and 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA, V) formed from the oxidation of 3-phenoxybenzyl alcohol (PBAlc, III) of type I pyrethroids and 3-phenoxybenzaldehyde (PBAld, IV) of type II pyrethroids. These metabolites can be excreted in urine as the amino acid (VII, VIII) or glucuronide conjugates (VI). The body burden of these metabolites as measured in urine is commonly used as a biomarker indicative of exposure to pyrethroid insecticides.

Figure 1.

Permethrin and cypermethrin, representatives of type I and II pyrethroid insecticides, respectively, and their major metabolic pathways in mammals. Immunoassays for the target analytes (I, V, VI, VII, and VIII) have been developed to evaluate environmental/human exposure to pyrethroid insecticides. IV is the direct hydrolysis product from type II pyrethroid insecticides, but is quickly oxidized to V. III is a direct hydrolysis product from type I pyrethroids.

Biomonitoring studies with samples such as urine and blood are measurements for the health-relevant assessments of exposure because they determine the level of the chemical that actually gets into people from all environmental routes such as air, soil, water, dust, or food. Biomarkers are indicators of changes or events in human biological systems (43). Considered as a chemical-specific biomarker of exposure, the unchanged parent molecule or specific biotransformation metabolite(s) that was derived from the parent organic substance of interest may persist a certain time in the human body after exposure. A concentration measured prior to and after exposure may show a level that would result in a biological response in susceptible populations. The general metabolites, 3-PBA and cis/trans-DCCA, of highly used pyrethroids such as permethrin, cyfluthrin, deltamethrin, cypermethrin, cyhalothrin, and transfluthrin can be measured in urine as an indicator of exposure (44). When the assay is validated, urine may be a better sampling medium than blood for monitoring because it is a sample matrix that can be obtained by non-invasive methods (45). The presence of a chemical-specific biomarker in urine can reflect the effects of recent exposures or of continuous exposure. Because pyrethroids are metabolized and eliminated very quickly, metabolites can only be detected within about 24 hours after exposure in urine (46).

Table 1 summarizes the immunoassays developed in this laboratory for the metabolites in a competitive indirect format based on polyclonal antibodies and a coating antigen as competitor. Immunoassays have proven successful for monitoring a large number of human biological samples in routine and rapid analyses. Primary target analytes for these immunoassays include 3-PBA, cis/trans-DCCA, glycine conjugates of 3-PBA and DCCA and a glucuronide conjugate (3-PBAlc-Glu) of 3-phenoxybenzyl alcohol. Sensitive analytical methods (LOQ: 0.01–0.4 µg/L urine) have been developed for the pyrethroid metabolites, 3-PBA and cis-/trans-DCCA. These methods are based on high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-tandem MS (47) or GLC-MS following acid hydrolysis and derivatization with hexafluoroisopropanol (46).

The sensitive ELISAs to measure glycine conjugates of esfenvalerate major metabolites, esfenvalerate acid (sFA), and 3-PBA were developed (48) based on a polyclonal antibody. With the aim of detecting the cis/trans-DCCA metabolites, several sensitive ELISAs with a heterologous configuration (cis/trans and trans/cis) between antibody specificity and hapten structure of the coating antigen were developed and optimized (49). The ELISA to detect a glucuronide conjugate (3-PBAlc-O-Glu) of 3-phenoxybenzyl alcohol (3-PBAlc) as a possible urinary biomarker also was developed (50). These selective immunoassays were successfully validated in human urine samples (48, 53). However, we recently conducted a human exposure study of permethrin that revealed that glycine conjugates of free metabolites and an ether type of glucuronide conjugate of 3-PBAlc are not the major metabolites. In contrast the less stable glucuronide esters may be more abundant in urine. Because sensitive and selective immunoassays for DCCA-glycine, and esfenvalerate acid-glycine were developed, these immunoassays, after glycine derivatization of the acidic metabolites, would be an alternative for monitoring 3-PBA and DCCA.

Since most pyrethroids like permethrin, cypermethrin and deltamethrin possess the phenoxybenzyl moiety, monitoring the general metabolite, 3-PBA as a urinary biomarker would allow the selective evaluation of human exposure to all pyrethroids and/or a single pyrethroid of interest containing this moiety. For this purpose, a sensitive immunoassay was developed based on a rabbit polyclonal antibody with an IC50 value of 1.65 µg/L (51). The 3-PBA ELISA is highly selective for the target analyte 3-PBA and the related cyfluthrin metabolite (4-fluoro-3-phenoxybenzoic acid). The ELISA (51) and a mixed-mode SPE (58) to reduce interferences in acid-hydrolyzed urine gave good recoveries (>100%) from spiked samples and allowed the accurate measurement of 3-PBA levels with a limit of quantification of 2 µg/L in unpublished data generated by our group. In an ongoing collaborative study, this method provided detectable urinary 3-PBA concentrations in around 74% of total urine samples collected from forest workers employed at sites in which pyrethroid insecticides were applied. However, levels found were not likely due to occupational exposure, but rather to exposure routes more similar to the general population since levels were not significantly elevated. When plasma samples are exposed to alkaline hydrolysis to generate 3-PBA from the parent compounds and the hydrolysate is exposed to sequential LLE and SPE, the resulting immunoassay has a similar LOQ to that in the urine.

An antibody-based biosensor approach for sensitivity and high through-put assay

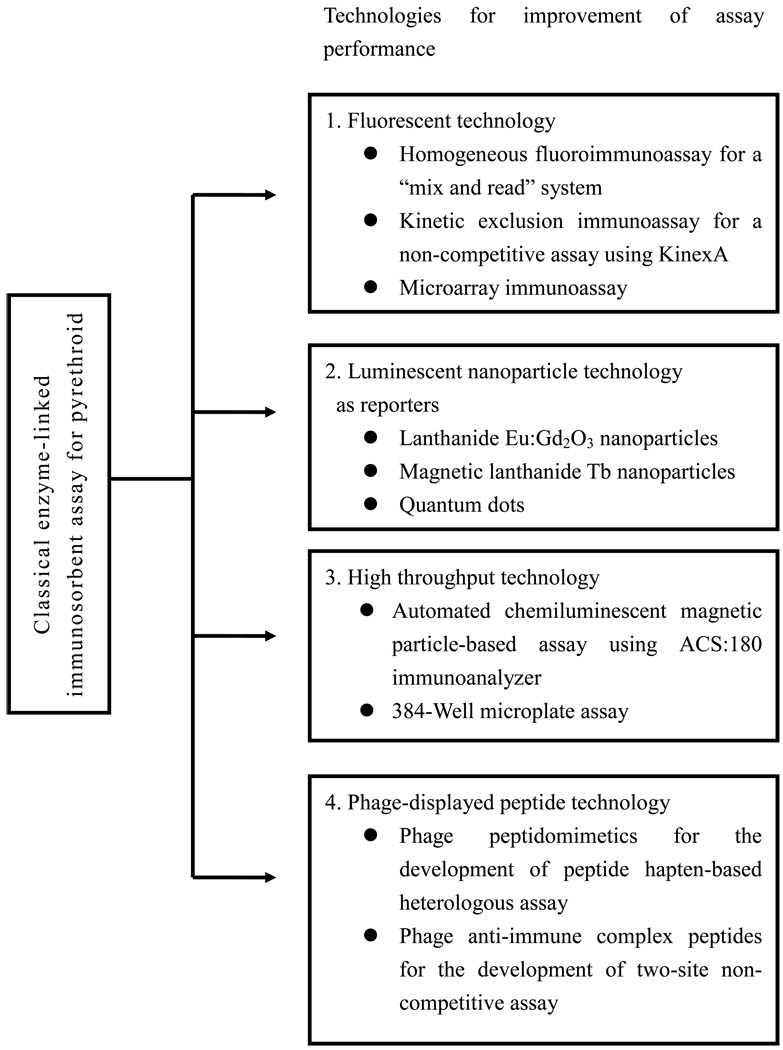

We continue to work toward increasing sensitivity and throughput of developed immunoassays using biosensor technology. Biosensors will provide improved speed, sensitivity, miniaturization, and sample preparation. One such possible improvement of assay sensitivity and performance would be to use labels such as unique emission fluorescent dyes and/or chemiluminescent materials. Detection of such labels ideally would be in a region of the spectrum where signal from naturally fluorescing and quenching materials is very low, thus reducing background interference caused from sample matrices. Separation steps with filtration or magnetic separation with paramagnetic particles can also reduce matrix effects. Micro- to nano-sized particles could also be used as the labels to enhance sensitivity and magnetic separation to maximize assay convenience, and application to microfluidic systems. A summary of some of our approaches is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A summary of technologies attempted in this laboratory to improve pyrethroid immunoassay performance from conventional competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for a pyrethroid and its metabolite.

Since 3-PBA is a common indicative metabolite to evaluate human exposure to pyrethroid insecticides, the 3-PBA assay has been used extensively to evaluate improvements of assay performance. We developed a simple one-step homogeneous fluoroimmunoassay for 3-PBA-glycine (54). The assay termed quenching fluoroimmunoassay (QFIA) was based on the competition between labeled competitor hapten and target analyte for the antibody binding. The major advantage of this assay is to reduce assay time eliminating multiple steps of washing and incubation.

A flow fluorescent immunoassay was developed for non-competitive detection of 3-PBA using a kinetic exclusion technique with a KinexA platform (55). This system uses a capillary column packed with micron sized beads immobilized with a hapten-protein conjugate. When a mixture of 3-PBA and its antibody was passed through the column, the unoccupied antibody was captured on the beads with antibody-analyte complex excluded from the binding event followed by the detection of captured antibody with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody. The assay sensitivity of this system performed in a homologous assay format was significantly increased, compared with the reported heterologous ELISA.

Europium ion and other lanthanides have been used as reporters for immunoassay both free and when complexed in a chelate. The lanthanides can be ideal labels because of their large Stoke’s shift, sharp emission peak, emission at wavelengths generally free of interference from natural biological fluorescence, and the ability to be measured in time-resolved mode. In our work, the inorganic Eu2O3 and Eu:Gd2O3 nanoparticles were used as novel fluorescent reporters in immunoassay and immunosensor approaches for measuring 3-PBA (52, 56). The Eu2O3-fluorescent immunoassay using a magnetic separation technique and the paramagnetic secondary antibody in the assay procedure remarkably improved sensitivity, compared to the conventional microplate ELISA for 3-PBA (51). However, the assay for 3-PBA-glycine using europium oxide particles generated with a microwave method was not as sensitive as the conventional microplate ELISA (48). This suggests that the coupling technique to link antibodies to the particle is important to increasing sensitivity. The Eu:Gd2O3 nanoparticles also were successfully applied as a reporter in a competitive fluorescence microimmunoassay for 3-PBA (56), however, sensitivity was not improved.

The application of quantum dots (QDs) generating different fluorescent emissions as labels in a microarray immunoassay for the multiplex detection of 3-PBA and other target analytes of interest has been demonstrated (57). Although attractive for multiplex assays, improvements in sensitivity are still needed using these labels. All of these approaches suggest the potential application of luminescent lanthanide nanoparticles and quantum dots as fluorescent probes in microarray and biosensor technology, immunodiagnostics, and high-throughput screening.

We have improved a competitive magnetic particle-based chemiluminescent assay for the detection of 3-PBA based on polyclonal antibodies with an automatic ACS:180 immunoassay analyzer system (58). The optimized competitive immunoassay format using a chemiluminescent acridinium ester label linked to a competitor-protein conjugate and a secondary antibody for the separation of immunocomplex and non-immunocomplex exhibited 20 times increased sensitivity for 3-PBA, compared t o that of the conventional microplate ELISA (51). This automated chemiluminescent immunoassay has excellent advantages in terms of sensitivity, rapidity, and simplicity for monitoring studies. Additionally, this common platform could be used to measure biomarkers of both exposure and effect in each sample.

Phage-borne peptide hapten-based competitive assay and non-competitive two-site phage anti-immune complex assay (PHAIA) for the detection of 3-PBA

Phage-displayed peptides can be used generally to improve a wide array of immunoassays (Table 3). In particular, when polyclonal antibodies are produced, the assay sensitivity can be improved by orders of magnitude if structural variants of the immunizing haptens are used for competition in a heterologous assay as shown in Table 1. Since the development of heterologous assay requires the synthesis of haptens, this technology is very attractive in laboratories with capability in organic synthesis. To facilitate the development of a sensitive heterologous assay, we took advantage of the huge diversity of phage-displayed peptide libraries in which each phage particle displays randomized 7–11 mer amino acids flanked with two cysteine residues fused to the gene III minor coat proteins of M13 bacteriophage. We selected phage-borne peptidomimetics by using biopanning that compete with 3-PBA over the binding pocket of 3-PBA polyclonal antibody. This antibody-coated competitive ELISA using these phage-borne peptidomimetics as competing peptide haptens exhibited a similar sensitivity compared to the synthetic hapten-based work (61). We also demonstrated that the phage particles can serve as a good binding scaffold for multiple binding of signal producing molecules. A chemiluminescent assay employing the phage particles labeled with acridinium (58) further improved the sensitivity around 2-fold (61), compared with that of the conventional ELISA.

Table 3.

Alternative immunoassay formats developed for the detection of the pyrethroid metabolite 3-PBA

| Target analyte | Assay probe | Assay performance |

Assay format | Sample matrix |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-PBA-glycine | Fluorescein | Automatic homogeneous quenching flow assay | Competitive direct | Urine | 54 |

| 3-PBA | Fluorescent Cy5 | Automated bead flow assay | Noncompetitive direct | Urine | 55 |

| 3-PBA-glycine | Luminescent lanthanide Eu-particles | Magnetic separation | Competitive indirect | Buffer | 56 |

| 3-PBA | Luminescent lanthanide Eu-particles | Magnetic separation | Competitive indirect | Buffer | 52 |

| 3-PBA | Luminescent lanthanide Eu:Gd2O3 particle | Microarray | Competitive direct | Buffer | 56 |

| 3-PBA | Quantum dot | Microarray | Competitive direct | Buffer | 57 |

| 3-PBA | Acridinium chemiluminescent | Automatic magnetic separation | Competitive indirect | Urine | 58 |

| 3-PBA | Acridinium chemiluminescent | Solution based assay | Competitive hapten mimic phage peptide | Buffer | 61 |

| 3-PBA | HRP enzyme linked | Dipstick | Noncompetitive phage anti-immunocomplex assay | Buffer | 60 |

| 3-PBA | HRP enzyme linked | Magnetic separation | Noncompetitive phage anti-immunocomplex assay | Urine | 62 |

It is known that non-competitive assays offer advantages over competitive assays in terms of assay sensitivity, and easy adaptability to other detection methods including immunochromatic method or biosensors (64). There have been many efforts in developing noncompetitive assays for small molecules. However, none of reported methods has been widely accepted due to the technical complexity and case-dependent successes. To develop a sensitive non-competitive assay for 3-PBA, we have recently introduced a novel non-competitive two-site assay termed phage anti-immune complex assay (PHAIA). The phage-borne peptides selected by biopanning a randomly produced peptide library are capable of forming a trivalent complex of antibody, 3-PBA, and peptide as the peptide recognizes the conformational change of an antibody binding pocket caused upon binding to 3-PBA, resulting in a sandwich type two-ligand complex (60, 62).

The resulting dose-response curve of the 3-PBA PHAIA showed significantly improved assay sensitivity (60), compared to that of the homologous competitive hapten-based microplate ELISA. We further demonstrated the application of the PHAIA to a magnetic bead-based assay (62). Magnetic beads have been widely used for various types of assays because separations are easily controlled as described above. We used commercially available streptavidin coated magnetic beads capturing 3-PBA antibody conjugated with biotin. The assay sensitivity of the bead-based PHAIA was similar to the PHAIA. However, the bead-based PHAIA required 10-fold less amount of antibody, indicating this method can be translated to an automatic biosensor approach. Moreover, unlike the typical competitive ELISAs, where low concentrations produce a high signal against a high background, the PHAIA is unique in that low concentrations generate a positive signal that is easily distinguishable from the signal intensity at zero concentration. We took advantage of this technology by adapting the PHAIA into a dipstick format which is useful for a rapid on-site monitoring of human exposure to pyrethroid insecticides (60). The difference in signals developed on a nitrocellulose strip on which the immobilized antibody captures 3-PBA and phage peptide could be read by the naked eye giving a very high assay sensitivity.

Ongoing studies

Luminescent lanthanide Tb core shell nanoparticles as an internal reference in immunoassay

Variability in assays can lead to poor reproducibility. This problem is often addressed in other analytical methods by using an internal standard. We hypothesized that immunoassays built on the surface of a fluorescent nanoparticle could yield such an internal standard for an immunoassay. Bifunctional magnetic-luminescent-nanoparticles with an iron oxide core and a silica shell doped with a Tb chelate (65) were prepared a s fluorescent labels and internal reference standards in a particle-based immunoassay. Because Tb emission is approximately 20 times brighter than the Eu emission studied above, assays may be performed in a reduced volume, a further step toward a miniaturized biosensor. The combination of magnetic and fluorescent properties is a new and powerful tool allowing manipulation by magnetic fields (for mixing, temperature control, separation, and flow control) and detection by fluorescence, compared with particles alone that are only fluorescent. These particles provide a biocompatible solid support to immobilize biomolecules such as hapten-protein conjugate and antibody on their surfaces by physical adsorption or chemical mediation. A competitive hapten-protein conjugate in this case was immobilized on iron-cored Tb-chelate doped silica shell nanoparticles functionalized with an amino group using an EDC coupling method. These particles competed with 3-PBA to react to a specific antibody. After magnetic separation, FITC- or TRITC-labeled secondary antibody was added for quantification. The assay outlined as one of our examples is described in Figure 3. The competitive particle-based immunoassays using organic dye-labeled- antibody for a reporter and Tb nanoparticles for an internal reference in a similar way (66) were demonstrated for 3-PBA measurement. The technique did not increase the assay sensitivity compared to the previously published work but did reduce variability.

Figure 3.

Fluorescent immunoassay for 3-PBA using iron-cored luminescent Tb shell nanoparticles. (a) The competitive hapten-linked protein conjugate was immobilized to the luminescent particle, and competed with 3-PBA to bind to specific antibody. After removing unbound immunocomplex by magnetic separation, the reporter FITC-labeled secondary antibody was added for quantification; (b) fluorescent signals of organic dyes (FITC or TRITC) as reporters and luminescent nanoparticles as a reference; (c) scanning of fluorescent signals of the luminescent nanoparticles complexed with the FITC-labeled antibody against various concentrations of 3-PBA in the range of 450 nm-550 nm, excited at 270 nm; (d) the standard curve represents the 3-PBA concentration dependence of the ratio between the fluorescence intensity of the FITC dye reporter (IFITC) and the intensity of the magnetic luminescent Tb particles (ITb).

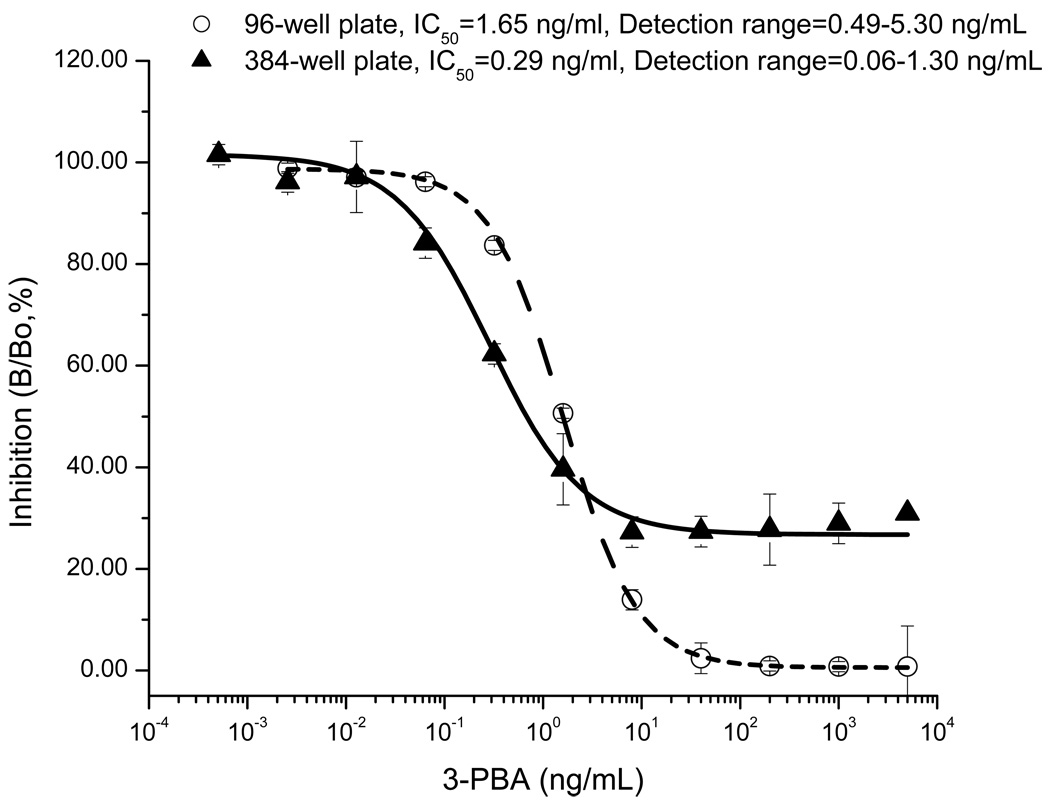

Miniaturization of immunoassays from a 96-well to 384-well format

This straightforward approach to increasing throughput has been demonstrated for the 3-PBA assay. When loading volumes of immunoreagents into each well that were reduced to half size in a 384-well plate, the assay sensitivity was increased 6 times, and the detection signal for 3-PBA was doubled, compared to a 96-well plate (51) (Figure 4). Reduced surface area in the well of the 384-well plate provides savings of valuable assay reagents, such as coating antigen, antibody, and secondary reporter antibody, as well as saving of buffers for washing and assay. A smaller surface area and assay volume improves diffusion kinetics, resulting in faster binding reactions. One drawback to miniaturization is that the label may not be present in a high enough amount to have a detectable signal. However, the surface area of 384-well plate to volume ratio is nearly double that of the 96-well plate. Therefore, the 384-well plate gives enhanced signal with an HRP enzyme label in solid phase reactions in which surface plays an important role in the assay. Another alternative would be to improve detectability using fluorescent dyes and luminescent probes such as lanthanides as described above. Certainly as reporters and detection methods improve, miniaturization of assays will be simplified. Pipetting is the largest source of error as assays are miniaturized. To minimize the contribution of pipetting to assay variability, we have demonstrated these assays using a robotic pipetting station.

Figure 4.

Comparison of ELISA inhibition curves for 3-PBA in 96-well (○) and 384-well (▲) plates. Loading volumes of immunoreagents such as coating antigen, and primary and secondary antibodies into a 384-well plate were reduced to a half of original volume of a 96-well plate; comparisons were the sensitivity and detection signal. IC50: Inhibition of 50% by 3-PBA

Immunoassays are mature and stable technologies in that the same methods reported by Hammock and Mumma (7) can still yield highly sensitive and selective analytical methods for both field and laboratory use at a low cost. However, this is an exciting time in the immunoassay field. A variety of technologies are coming together in a synergistic fashion resulting in improvements in sensitivity, reproducibility, and speed. In particular advances both in physics and engineering on one side and biology on the other dramatically simplifies miniaturization and multiplexing of assays.

Further studies

We are working on various immunoassay technologies such as fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) and fluorescent polarization using immunoreagents such as antibodies, phage displayed peptides, competitive hapten mimics, magnetic luminescent nanoparticles, and its paired fluorescent dyes. These reagents provide homogeneous and heterogeneous analytical formats for immunoassay and biosensor approaches. For example, an immunochromatographic lateral-flow assay using gold nanoparticles and our new noncompetitive phage anti-immunocomplex-based dipstick technology (60) may provide a simple and sensitive assay, which would be suitability for the rapid detection of 3-PBA.

Recently we have been producing camelid antibodies to small and big molecular weight targets in the laboratory. The targets of interest in the laboratory include pesticides, toxins, and enzymes including the pyrethroid metabolite 3-PBA, triclocarban, paraquat, ricin, soluble epoxide hydrolase, and juvenile hormone esterase. Some of the antibodies that are produced by animals such as alpaca and llama in the camelid family contain no light chains; yet they retain all the binding specificity and sensitivity of their two chain counterparts. The very tip of these heavy chain antibodies, called a single domain heavy chain, is very stable and soluble and can be recombinantly expressed in E. coli in high yields (67). Also, these recombinant proteins are heat and matrix resistant, properties that can make them ideal for use in field portable biosensors. As the first output, we generated highly sensitive and selective llama single domain heavy chain recombinant antibodies for the detection of low levels of the antimicrobial triclocarban. This research is translating to the generation of such antibodies for 3-PBA.

These various approaches aim to find a system that is well suited for human and environmental samples, making immunoassays even more valuable tools for bio and environmental monitoring. The techniques described using the antibodies, hapten competitor, phage displayed peptide, and luminescent nanoparticles and are already developed for some pyrethroid targets in the laboratory, and compare well with the conventional immunoassay in terms of sensitivity, assay time, and simplicity.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the many colleagues and co-workers who, over the last few years, contributed their efforts to immunoassay development for pyrethroid insecticides and their metabolites. We give special thanks to our long term collaborators Professors Ian Kennedy (UC Davis) and Gualberto G. González-Sapienza (UDELAR, Uruguay) for luminescent particle-based biosensor and novel binding reagents. Financial support for some of this research was received from the NIEHS Superfund Basic Research Program 5P42 ES04699, NIEHS (R01 ES02710), the UC Davis Center for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention (1PO1 ES11269), and the NIOSH Center for Agricultural Disease and Research, Education and Prevention (1 U50 OH07550).

Literature Cited

- 1.Vanderlaan M, Stanker L, Watkins B. Immunochemical techniques in trace residue analysis. In: Vanderlaan M, Stanker L, Watkins B, editors. Immunoassays for Trace Chemical Analysis: Monitoring Toxic Chemicals in Humans, Food, and the Environment; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society; Washington, D. C. 1991. pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esser T, Karu AE, Toia RF, Casida JE. Recognition of tetramethylenedisulfotetramine and related sulfamides by the brain GABA-gated chloride channel and a cyclodiene-sensitive monoclonal antibody. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1991;4:162–167. doi: 10.1021/tx00020a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abernathy CO, Casida JE. Pyrethroid insecticides: esterase cleavage in relation to selective toxicity. Science. 1973;179:1235–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4079.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casida JE, Ueda K, Gaughan LC, Jao LT, Soderlund DM. Structure-biodegradability relationships in pyrethroid insecticides. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1975–1976;3:491–500. doi: 10.1007/BF02220819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing KD, Hammock BD, Wustner DA. Development of an S-bioallethrin specific antibody. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978;26:1328–1333. doi: 10.1021/jf60220a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wing KD, Hammock BD. Stereoselectivity of a radioimmunoassay for the insecticide S-bioallethrin. Experientia. 1979;35:1619–1620. doi: 10.1007/BF01953227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammock BD, Mumma R. Potential of immunochemical technology for pesticide residue analysis. In: Harvey J Jr, Zweig G, editors. Recent Advances in Pesticide Analytical Methodology; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society; Washington, D. C.. 1980. pp. 321–352. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall EAH. Overview of biosensors. In: Edelman PG, Wang J, editors. Biosensor and Chemical sensors; optimizing performance through polymeric materials; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society; Washington, D. C.. 1992. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pullen S, Hock B. Development of enzyme immunoassays for the detection of pyrethroid insecticides 1. Monoclonal antibodies for allethrin. Analytical Letters. 1995;28:765–779. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao H, Ling Y, Xu T, Zhu W, Jing H, Sheng W, Li QX, Li J. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the pyrethroid insecticide cyhalothrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:5284–5291. doi: 10.1021/jf0607009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H-J, Shan G, Ahn KC, Park E-K, Watanabe T, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the pyrethroid cypermethrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:1039–1043. doi: 10.1021/jf030519p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H-J, Shan G, Watanabe T, Stoutamire DW, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the pyrethroid deltamethrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:5526–5532. doi: 10.1021/jf0207629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee N, McAdam DP, Skerritt JH. Development of immunoassays for type II synthetic pyrethroids. 1. Hapten design and application to heterologous and homologous assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:520–534. doi: 10.1021/jf970438r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skerritt JH, Hill AS, McAdam DP, Stanker LH. Analysis of the synthetic pyrethroids, permethrin and 1(R)-phenothrin, in grain using a monoclonal antibody-based test. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992;40:1287–1292. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shan G, Stoutamire DW, Wengatz I, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Development of an immunoassay for the pyrethroid insecticide esfenvalerate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999;47:2145–2155. doi: 10.1021/jf981210m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyake S, Hayashi A, Kumeta T, Kitajima K, Kita H, Ohkawa H. Effectiveness of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies prepared for an immunoassay of the etofenprox insecticide. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1998;62:1001–1004. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wengatz I, Stoutamire D, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Development of an ELISA for the detection of the pyrethroid insecticide fenpropathrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:2211–2221. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakata M, Fukushima A, Ohkawa H. A monoclonal antibody-based ELISA for the analysis of the insecticide flucythrinate in environmental and crop samples. Pest Manag. Sci. 2001;57:269–277. doi: 10.1002/ps.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan G, Leeman WR, Stoutamire DW, Gee SJ, Chang DPY, Hammock BD. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the pyrethroid permethrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:4032–4040. doi: 10.1021/jf000351x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyake S, Beppu R, Yamaguchi Y, Kaneko H, Ohkawa H. P olyclonal and monoclonal antibodies specific to the chrysanthemic acid moiety of pyrethroid insecticides. Pesti. Sci. 1999;54:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watanabe T, Shan G, Stoutamire DW, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Development of a class-specific immunoassay for the type I pyrethroid insecticides. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2001;444:119–129. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mak SK, Shan G, Lee H-J, Watanabe T, Stoutamire DW, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Development of a class selective immunoassay for the type II pyrethroid insecticides. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2005;534:109–120. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao XL, Kuang H, Li YL, Yuan Y, Peng CF, Chen W, Wang LB, Xu CL. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the alpha-cyano pyrethroids multiresidue in Tai lake water. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:3033–3039. doi: 10.1021/jf803807b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Q, Zhang W, Wang X, Li P. Immunoassay development for the class-specific assay for types I and II pyrethroid insecticides in water samples. Molecules. 2010;15:164–177. doi: 10.3390/molecules15010164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaware M, Bronshtein A, Safi J, Van Emon JM, Chuang JC, Hock B, Kramer K, Altstein M. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and sol-gel-based immunoaffinity purification (IAP) of the pyrethroid bioallethrin in food and environmental samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:6482–6492. doi: 10.1021/jf0607415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park E-K, Kim J-H, Gee SJ, Watanabe T, Ahn KC, Hammock BD. Determination of pyrethroid residues in agricultural products by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:5572–5576. doi: 10.1021/jf049438z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichkova M, Fu X, Yang Z, Zhong P, Sanborn JR, Chang D, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Immunochemical screening of pesticides (simazine and cypermethrin) in orange oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:5673–5679. doi: 10.1021/jf900652a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H-J, Watanabe T, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Application of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to determine deltamethrin residues in milk. B. Environ. Contam. Tox. 2003;71:14–20. doi: 10.1007/s00128-003-0124-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang Y, Zhou S, Hu L, Li L, Zhao M, Liu H. Class-specific immunoaffinity monolith for efficient on-line clean-up of pyrethroids followed by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2010;878:278–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabral JR, Galendo D, Laval M, Lyandrat N. Carcinogenicity studies with deltamethrin in mice and rats. Cancer Lett. 1990;49:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(90)90151-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shukla Y, Yadav A, Arora A. Carcinogenic and cocarcinogenic potential of cypermethrin on mouse skin. Cancer Lett. 2002;182:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madsen C, Claesson MH, Ropke C. Immunotoxicity of the pyrethroid insecticides deltamethrin and alpha-cypermethrin. Toxicology. 1996;107:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(95)03244-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diel F, Horr B, Borck H, Irman-Florjanc T. Pyrethroid insecticides influence the signal transduction in T helper lymphocytes from atopic and nonatopic subjects. Inflamm. Res. 2003;52:154–163. doi: 10.1007/s000110300066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grosman N, Diel F. Influence of pyrethroids and piperonyl butoxide on the Ca2+-ATPase activity of rat brain synaptosomes and leukocyte membranes. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray DE. Pesticide neurotoxicity in Europe: real risks and perceived risks. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21:219–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdel-Rahman A, Dechkovskaia AM, Goldstein LB, Bullman SH, Khan W, El-Masry EM, Abou-Donia MB. Neurological deficits induced by malathion, DEET, and permethrin, alone or in combination in adult rats. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 2004;67:331–356. doi: 10.1080/15287390490273569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shafer TJ, Meyer DA, Crofton KM. Developmental neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides: critical review and future research needs. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:123–136. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta A, Agarwal R, Shukla GS. Functional impairment of blood-brain barrier following pesticide exposure during early development in rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 1999;18:174–179. doi: 10.1177/096032719901800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinha C, Agrawal AK, Islam F, Seth K, Chaturvedi RK, Shukla S, Seth PK. Mosquito repellent (pyrethroid-based) induced dysfunction of blood-brain barrier permeability in developing brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2004;22:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitmore RW, Immerman FW, Camann DE. Non-occupational exposures to pesticides for residents of two US cities. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1993;26:1–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00212793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis RG, Fortman RC, Camann DE. Evaluation of methods for monitoring the potential exposure of small children to pesticides in the residential environment. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1994;26:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00212792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hwang HM, Park EK, Young TM, Hammock BD. Occurrence of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in indoor dust. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;404:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Research Council. Use of biological markers in assessing human exposure to airborne contaminants. In: NRC, editor. Human exposure assessment for airborne pollutants: advances and opportunities. Washington, D.C.: National academy of sciences; 1991. pp. 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Columé A, Cárdenas S, Gallego M, Valcárcel M. A solid phase extraction method for the screening and determination of pyrethroid metabolites and organochlorine pesticides in human urine. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:2007–2013. doi: 10.1002/rcm.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith TM, Suk WA. Application of molecular biomarkers in epidemiology. Environ. Health Perspect. 1994;102:229–235. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gabriele L, Wolfgang G. Simultaneous determination of pyrethroid and pyrethrin metabolites in human urine by gas chromatography- high resolution mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B, Analytical Technologies in the Biomedical and Life Sciences. 2005;814:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olsson AO, Baker SE, Nguyen JV, Romanoff LC, Udunka SO, Walker RD, Flemmen KL, Barr DB. A liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry multiresidue method for quantification of specific metabolites of organophosphorus pesticides, synthetic pyrethroids, selected herbicides, and DEET in human urine. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:2453–2461. doi: 10.1021/ac0355404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shan G, Wengatz I, Stoutamire DW, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of esfenvalerate metabolites in human urine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1999;12:1033–1041. doi: 10.1021/tx990091h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahn KC, Watanabe T, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Hapten and antibody production for a sensitive immunoassay determining a human urinary metabolite of the pyrethroid insecticide permethrin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:4583–4594. doi: 10.1021/jf049646r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim HJ, Ahn KC, Ma SJ, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Development of sensitive immunoassays for the detection of the glucuronide conjugate of 3-phenoxybenzyl alcohol, a putative human urinary biomarker for pyrethroid exposure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:3750–3757. doi: 10.1021/jf063282g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shan G, Huang H, Stoutamire DW, Gee SJ, Leng G, Hammock BD. A sensitive class specific immunoassay for the detection of pyrethroid metabolites in human urine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004;17:218–225. doi: 10.1021/tx034220c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahn KC, Gee SJ, Kim H-J, Nichkova M, Lee NA, Hammock BD. Progress in the development of biosensors for environmental and human monitoring of agrochemicals. In: Kennedy IR, Solomon KR, Gee SJ, Crossan AN, Wang S, Sánchez-Bayo F, editors. Rational Environmental Management of Agrochemicals; ACS Symposium Series, American Chemical Society; Washington, D. C.. 2007. pp. 138–154. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahn KC, Ma S-J, Tsai H-J, Gee JG, Hammock BD. An immunoassay for a human urinary metabolite as a biomarker of human exposure to the pyrethroid insecticide permethrin. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006;384:713–722. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-0220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matveeva EG, Shan G, Kennedy IM, Gee SJ, Stoutamire DW, Hammock BD. Homogeneous fluoroimmunoassay of a pyrethroid metabolite in urine. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2001;444:103–117. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim H-J, Gee SJ, Li QX, Hammock BD. Noncompetitive fluorescent immunoassay for the detection of the human urinary biomarker 3-phenoxybenzoic acid with bench top immunosensor KinExA™ 3000. In: Kennedy IR, Solomon KR, Gee SJ, Crossan AN, Wang S, Sánchez-Bayo F, editors. Rational Environmental Management of Agrochemicals; ACS Symposium Series, American Chemical Society; Washington, D. C.. 2007. pp. 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nichkova M, Dosev D, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Kennedy IM. Microarray immunoassay for phenoxybenzoic acid using polymer encapsulated Eu:Gd2O3 nanoparticles as fluorescent labels. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6864–6873. doi: 10.1021/ac050826p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nichkova M, Dosev D, Davies AE, Gee SJ, Kennedy IM, Hammock BD. Quantum dots as reporters in multiplexed immunoassays for biomarkers of exposure to agrochemicals. Anal. Lett. 2007;40:1423–1433. doi: 10.1080/00032710701327088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahn KC, Lohstroh P, Gee SJ, Gee NA, Lasley B, Hammock BD. High-throughput automated luminescent magnetic particle-based immunoassay to monitor human exposure to pyrethroid insecticides. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:8883–8890. doi: 10.1021/ac070675l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stanker LH, Bigbee C, Van Emon J, Watkins B, Jensen RH, Morris C, Vanderlaan M. An immunoassay for pyrethroids: detection of permethrin in meat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1989;37:834–839. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonzalez-Techera A, Kim HJ, Gee SJ, Last JA, Hammock BD, Gonzalez-Sapienza G. Polyclonal antibody-based noncompetitive immunoassay for small analytes developed with short peptide loops isolated from phage libraries. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:9191–9196. doi: 10.1021/ac7016713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim HJ, Gonzalez-Techera A, Gonzalez-Sapienza GG, Ahn KC, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Phage-borne peptidomimetics accelerate the development of polyclonal antibody-based heterologous immunoassays for the detection of pesticide metabolites. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:2047–2053. doi: 10.1021/es702219a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim HJ, Ahn KC, Gonzalez-Techera A, Gonzalez-Sapienza GG, Gee SJ, Hammock BD. Magnetic bead-based phage anti-immunocomplex assay (PHAIA) for the detection of the urinary biomarker 3-phenoxybenzoic acid to assess human exposure to pyrethroid insecticides. Anal. Biochem. 2009;386:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee N, Beasley HL, Skerritt JH. Development of immunoassays for type II synthetic pyrethroids. 2. Assay specificity and application to water, soil, and grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:535–546. doi: 10.1021/jf970439j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jackson TM, Ekins RP. Theoretical limitations on immunoassay sensitivity current practice and potential advantage of fluorescent Eu3+ chelates as non-radioisotopic tracers. J. Immunol. Methods. 1986;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma Z, Dosev D, Nichkova M, Dumas RK, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Liu K, Kennedy IM. Synthesis and characterization of multifunctional silica core-shell nanocomposites with magnetic and fluorescent functionalities. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2009;321:1368–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nichkova M, Dosev D, Gee SJ, Hammock BD, Kennedy IM. Multiplexed immunoassays for proteins using magnetic luminescent nanoparticles for internal calibration. Anal. Biochem. 2007;369:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muyldermans S, Baral TN, Retamozzo VC, De Baetselier P, De Genst E, Kinne J, Leonhardt H, Magez S, Nguyen VK, Revets H, Saerens D. Camelid immunoglobulins and nanobody technology. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2009;128:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.10.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]