Abstract

Background

Endoscopic inguinal hernia repair was introduced in the Netherlands in the early 1990s. The authors’ institution was among the first to adopt this technique. In this study, long-term hernia recurrence among patients treated by the total extraperitoneal (TEP) approach for an inguinal hernia is described. A cohort study was conducted.

Methods

Between January 1993 and December 1997, 346 TEP hernia repairs were performed for 318 patients. After a mean follow-up period of 13-years, a senior resident examined each patient. An experienced surgeon subsequently examined the patients with a diagnosis of recurrent hernia. Data were collected on an intention-to-treat basis, meaning that conversions were included in the analysis. Univariant tests were used to analyze age older than 50 years, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, body mass index, smoking habit, hernia type, history of open hernia repair, conversion, and surgeon as potential risk factors.

Results

The analysis included 191 patients (62%) with 213 hernias. Of the original 318 patients, 59 patients died, and 68 were lost to follow-up evaluation. Perioperatively, 105 lateral, 55 medial, and 53 pantalon hernias were observed. Of the 213 hernias, 176 were primary and 37 were recurrent. The overall recurrence rate was 8.9% (8.5% for primary and 10.8% for recurrent hernias). Of the total study group, 48% of the patients experienced a bilateral inguinal hernia during their lifetime. No predicting factor for recurrent hernia could be identified.

Conclusions

The current long-term results for TEP repair of primary and secondary inguinal hernia show an overall recurrence rate of 8.9%, which is slightly higher than in previous studies. The thorough examination at follow-up assessment, the learning curve effect, and the intention-to-treat-analysis may have influenced the observed recurrence rate. Also, the percentage of bilateral hernias was higher than known to date. Therefore, examination of the contralateral side should be standard procedure.

Keywords: Bilateral hernia, Endoscopic hernia repair, Inguinal hernia, Long term, Recurrence rate, TEP

Endoscopic inguinal hernia repair was introduced in the Netherlands in 1991 [1], initially with the transabdominal preperitoneal polypropylene (TAPP) approach, followed shortly thereafter by the total extraperitoneal (TEP) approach [2–4]. Previously, we reported on the medium-term results for the first cohort of our patients [5, 6].

Currently, TEP repair is the preferred technique for endoscopic inguinal hernia repair in The Netherlands. Although endoscopic inguinal hernia repair is known for its faster recovery, earlier return to work, and thus less societal cost than open repair [7], the 2003 Dutch guideline on inguinal hernia repair does not consider endoscopic repair the first treatment option [8], similar to the 2004 National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline [9]. For primary hernias, the Lichtenstein inguinoplasty is recommended. The TEP repair is recommended for bilateral hernia and for recurrent hernia when an anterior technique has been used for the primary repair.

In experienced hands, TEP also can be considered for primary hernia repair. This advice is based on the suggested complexity of endoscopic repair and the higher in-hospital cost for a unilateral operation. Additionally, some authors have described a long learning curve [10–12]. In experienced hands, however, favorable results for the endoscopic technique have been reported [10].

In the Netherlands about 30,000 groin hernias are repaired annually. Optimizing the surgical technique and reducing the recurrence rate have a major socioeconomic impact. This report describes the long-term recurrence rate after TEP for a cohort of patients who underwent surgery before presentation of the Dutch guidelines.

Materials and methods

A cohort of TEP patients was selected who had surgery at least 10 years previously after the first learning curve of 30 procedures per surgeon. Between January 1993 and December 1997, 318 patients underwent 346 hernia repairs. Bilateral hernias and those perioperatively converted to a transabdominal or open approach were included in the study.

Three surgeons performed all except one of the operations. Two of these surgeons changed hospital of employment during the study period. The three surgeons performed an average of 1 or 2 procedures a week.

The operative technique has been described previously [18]. Through an infraumbilical incision, the ipsilateral anterior rectus sheath was opened. A balloon trocar was used to dissect the preperitoneal space. A blunt-tip trocar with carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation and a 0º laparoscope were introduced into the preperitoneal space. The lateral dissection was performed mainly under direct vision using the laparoscope. Two additional trocars were subsequently introduced: one 10 mm inferomedial to the anterior superior iliac spine and one 5 mm in the midline one-third of the distance from the umbilicus to the pubic bone.

The pubic bone and the epigastric vessels were identified. Dissection of the preperitoneal space was caudally 2 to 3 cm behind the pubic bone, medially a few centimeters across the midline, and craniolaterally close to the anterosuperior iliac spine. Laterally, the nerves running on the ileopsoas muscle were carefully avoided. The peritoneal reflection was reduced 8 to 10 cm cranially from the internal inguinal opening to avoid getting the peritoneum caught between the mesh and the spermatic cord.

A 10 × 15-cm polypropylene mesh (Prolene; Ethicon GmbH) was introduced into the preperitoneal space, covering the inguinal floor. Mesh fixation was incidentally performed with tacks in case of a very large medial defect. Under vision, maintenance of the correct mesh position during CO2 desufflation was checked. The anterior rectus sheath was closed with 2–0 polyglactin sutures (Vicryl; Ethicon GmbH).

The following parameters were recorded: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), operating surgeon, hernia location, operation time, use of drains or prophylactic antibiotics, peri- and postoperative complications, and duration of hospital stay. The majority of patients had surgery in day care and were allowed to mobilize as soon as they felt up to it. No specific restrictions with regard to mobilization or exercise were given. Patients were seen in the outpatient clinic at regular intervals during the first 2 years.

For this study, all patients were contacted by mail and invited for a visit to the outpatient clinic. If they did not respond to a second mailing, they were contacted by telephone, or an effort was made to obtain their current address from their general practitioner or insurance company. Of the original 318 patients, 59 had died and 68 were lost to follow-up, either because they had moved and had an untraceable new address or because they declined the invitation.

Consequently, 191 patients with 213 TEPs were included in the study. History was taken, and the first author (AB-K), a senior resident, performed physical examination.

All the patients answered a questionnaire, reporting pre- and postoperative complaints and possible risk factors such as a smoking habit, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), abdominal aortic aneurysm, obstipation, and prostatism. In case patients had already undergone surgery for a recurrent hernia, the data for this operation were collected.

Examination was performed with the patient supine and standing, with and without the Valsalva maneuver. In this way, asymptomatic recurrences could be detected. A recurrence was defined as clear bulging of the abdominal wall along the course of the inguinal canal or from the exterior inguinal ring, with reposition at relaxation.

Patients with a diagnosis of asymptomatic recurrent hernia or asymptomatic contralateral primary hernia were subsequently examined by an experienced surgeon (L.S.), and the diagnosis was confirmed by a radiologist (N.R.) using abdominal ultrasound.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis was performed to identify potential risk factors for the development of hernia recurrence after TEP. When a variable met the univariate criterion (p < 0.1, χ2 test), the variable was considered further for multivariable logistic regression analysis, with recurrent hernia as the dependent variable. A p value less than 0.050 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 14.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Patients’ demographics and results of the univariant χ2 analysis

| n | Recurrence n (%) | χ2 (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 208 | 19 (9.1) | |

| Female | 5 | 0 | |

| Smoking | 68 | 6 (8.8) | |

| BMI: mean (range) | 24.9 (20.3–30.3) | 25.1 (22.0–28.7) | |

| Age at operation >50 years | 107 | 13 (12.1) | 0.231 |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 3 | 0 | |

| COPD | 17 | 3 (17.6) | 0.188 |

| Prostatism | 32 | 3 (9.4) | |

| Obstipation | 16 | 1 (6.2) | |

CI confidence interval, BMI body mass index, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Table 2.

Operation characteristics compared between total group and recurrence group and results of the univariant χ2 analysis

| n | Recurrence n (%) | χ2 (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 213 | 19 (8.9) | |

| Medial | 55 | 7 (13) | |

| Type of hernia | |||

| Lateral | 105 | 9 (8.5) | 0.816 |

| Pantalon | 53 | 4 (7.5) | |

| Type of hernia | |||

| Recurrent | 37 | 5 (13.5) | 0.657 |

| Primary | 176 | 15 (8.5) | |

| Side | |||

| Left | 90 | 6 (6.7) | |

| Right | 97 | 12 (12.4) | |

| Bilateral | 13 | 1 (7.8) | |

| Mean operation time (min) | 45 | 50 | |

| Operator | |||

| Surgeon 1 | 79 | 5 (5.2) | 0.307 |

| Surgeon 2 | 42 | 6 (14.2) | |

| Surgeon 3 | 91 | 6 (6.5) | |

| Rest | 1 | 1 | |

| Operation | |||

| Antibiotics | 86 | 8 (9.3) | |

| Conversion | 13 | 2 (15.4) | |

CI confidence interval

Results

This study enrolled 191 patients (186 men and 5 women) with 213 TEPs (including 13 synchronic bilateral procedures and 9 metachronic bilateral procedures), for a follow-up rate of 62%. The mean age at surgery was 51 years (range, 19–72 years), and the mean BMI was 24.9 kg/m2 (range, 18.9–30.3 kg/m2).

Perioperatively, 105 lateral, 55 medial, and 53 pantalon hernias were observed. Of the 213 hernias, 176 were primary and 37 recurrent. There were 97 right sided, 90 left-sided, and 13 bilateral hernias. The mean follow-up period was 13 years. The overall recurrence rate was 8.9%: 8.5% (15/176) for primary and 10.8% (4/37) for recurrent hernias. Of the 19 recurrences, 9 (8.5%) were asymptomatic, as identified during follow-up evaluation. The remainder had already been corrected surgically.

Tables 1 and 2 present the patients’ demographics and the general operation characteristics. The results of the univariate analysis also are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

No predictor variable met the inclusion criteria for multivariate analysis. Therefore, this analysis was not performed.

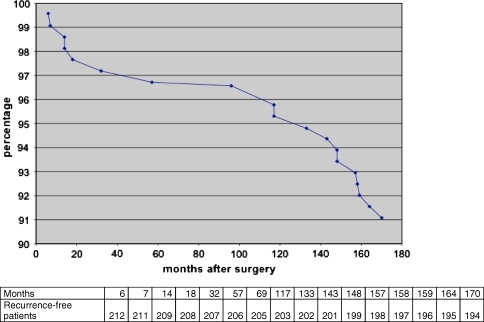

The Kaplan Meyer curve in Fig. 1 illustrates a steady increase in the incidence of recurrent hernias throughout the 13-year follow-up period. Two distinct periods with a higher incidence of recurrence can be identified: the first 3 years and the last year. The first peak resembles a true phenomenon because these recurrences were diagnosed mostly during the period when patients still were seen frequently at the outpatient clinic. Diagnosis of asymptomatic recurrences due to the study protocol caused the second peak.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve indicating the percentage of recurrence-free patients: manifestation of recurrence over time for 213 inguinal hernias treated by total extraperitoneal (TEP) procedure

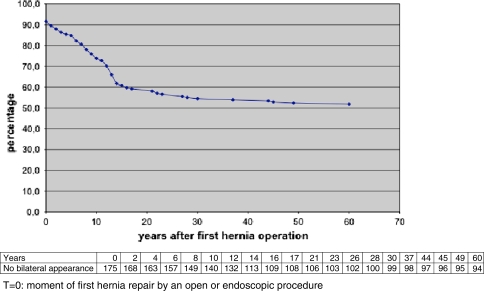

Almost half of the patients (n = 92, 48%) experienced the development of a bilateral inguinal hernia during their lives. Of these 92 patients, 74 had undergone surgery before or after their TEP repair. The remaining 18 cases were found during the follow-up period. Only 19 patients had a synchronous bilateral correction (6 open and 13 TEP). Open correction of the contralateral side was performed for 36 patients, 34 of whom had the correction before the TEP procedure. A total of 19 patients had a contralateral TEP procedure after the previous ipsilateral TEP repair. The 18 asymptomatic patients found during the follow-up period did not undergo surgery.

As shown by Fig. 2, the odds for the development of a bilateral hernia are highest in the first 15 years after the appearance of the first hernia (rate ratio, 0.08). During the follow-up period, 27 asymptomatic hernias (recurrent after TEP or contralateral) were found. These hernias were confirmed either by physical examination performed by an experienced surgeon (L.S.) or by ultrasound if necessary. Of the 191 patients, 187 (98%) would recommend the TEP to other patients for correction of an inguinal hernia.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve indicating the percentage of patients with a unilateral inguinal hernia in a cohort of 191 patients treated by total extraperitoneal (TEP) procedure. T time in years

Discussion

To date, information on the long-term results after TEP is sparse. Most studies provide short- or medium-term results, with recurrence rates ranging from 2% to 6% [7, 13–16]. Recently, Surgical Endoscopy published a 10-year follow-up study with favorable recurrence rates of 4% after primary and 11% after recurrent hernia repair [17]. These results may be biased by selection because the data originated from specialist centers. Moreover, physical examination was not standard for all the subjects during the follow up period. Therefore, asymptomatic patients may not always be identified. Moreover, patients for whom the TEP procedure was converted to a TAPP or open correction were not included in these studies.

The current study is the first to report on a 13-year follow-up period after TEP endoscopic inguinal hernia repair. The overall recurrence rate was 8.9%. We observed an 8.5% recurrence rate after primary repairs and a 10.8% rate for recurrent hernias. Furthermore, a gradual increase in recurrences over the years was noted. Short-term (2 years) recurrence rates after TEP, as found in large randomized controlled trials, vary from 2 to 10.1% [10, 18]. This rise also is illustrated by comparison with a previous report on a subgroup of the patients from the current cohort who had surgery between January 1993 and July 1995.

Our recurrence rate of 8.5% for primary hernias is consistent with the figures published by Neumayer et al. [10] and, as mentioned earlier, could have been anticipated from our previous study results [5, 6]. Nevertheless, the recurrence rate for this cohort may be considered somewhat high compared with other reports. The Dutch [8] and NICE [9] Guidelines of 2003 and 2004 considered endoscopic repair equal to anterior mesh repair in terms of the risk for recurrence. Neumayer et al. [10], however, showed a recurrence rate of 4.8% for the open mesh group. The aforementioned report on nonendoscopic hernia repair [19] found a 1% recurrence rate in the mesh group after 10 years. Another retrospective series on long-term results after TEP [17] reported a 4% recurrence rate after primary repair with a 10-year follow-up period.

Our recurrence rate may be explained by the following factors. First, the study population was a cohort of all consecutive patients who had surgery between January 1993 and December 1997. When the operation was converted to TAPP or an anterior approach, the patients still were included on an intention-to-treat principle. If these patients were excluded, the recurrence rates would be 8.5%: 7.7% for the primary and 12.5% for the recurrent repair group. In most other studies, no physical examination is performed, or it is given only to symptomatic patients. If the asymptomatic hernias were excluded, our overall recurrence rate would be 4.7%: 4% for primary and 8.1% for recurrent hernias.

The second factor is the possible influence of a learning curve effect. Previously, the learning curve has been shown to comprise 30 endoscopic repairs [20]. Meanwhile, the curve has been suggested to include as many as 250 procedures [10]. Clearly, experience increases with the number of procedures performed. The three surgeons in this study had performed more than 30 procedures each but fewer than 100. The more frequent recurrences in the first 3 years (Fig. 1) may illustrate the learning curve, as described earlier [5]. A learning curve effect is also suggested by the aforementioned report of Staarink et al. [17].

Two of the surgeons started performing endoscopic hernia repair in the early 1990s. They were initially trained by an international proctor. Further experience was gained by attending national and international workshops and by performing operations with both surgeons on the team. The third surgeon started this surgery some years later and was fully trained by Dutch proctors.

Performing TEP repair for both primary and recurrent hernias is not in conflict with the Dutch guidelines. In the first place, the operations were performed several years before the guideline was issued. Second, although in general the guideline promotes the Lichtenstein repair as the first choice treatment for primary repairs, endoscopic surgery is considered a good technique in experienced hands. The surgeons in the current study can be considered as meeting this criterion, having adopted the technique in its early days with a steadily increasing number of operations performed each year.

Unfortunately, a large number of patients died or were lost to follow-up evaluation. This phenomenon is well known from long-term inguinal hernia studies [17, 19]. Our reports would of course have gained in accuracy with more complete follow-up evaluation.

In The Netherlands, the mesh usually is not fixed. The short-term results for this technique were favorable [18], and all other Dutch reports are based on the same technique. In the United States, meshes are more often fixed. Whether the high incidence of recurrence reported by Neumayer et al. [10] occurred despite mesh fixation is not mentioned in the study. As described earlier, we only incidentally used fixation of the mesh with tacks. This was performed when a large medial hernia defect was present and migration of the mesh edge into the defect was considered a risk. Whether standard fixation of the mesh would positively influence long-term results remains to be seen.

We did not observe a relation of smoking habit, COPD, type of hernia, age older than 50 years, BMI, and surgeon who performed the operation to the risk of recurrence. This contrasts with other studies showing that age older than 50 years [21] and smoking [22] are significant risk factors. However, the number of patients in our subgroups were relatively small, which may have concealed an effect.

A remarkably high percentage (48%) of bilateral hernias was observed in our patients. The contralateral hernia presented before or during the follow-up period. Our findings, as illustrated by Fig. 2, suggest that the contralateral occurrence appears especially during the first 15 years after presentation of the first hernia,. Additional attention and thorough examination of the symptomatic and asymptomatic sides at presentation and during follow-up evaluation may help to show these, and appropriate treatment should be discussed with the patient.

Conclusions

The current long-term results of TEP repair for inguinal hernias show an overall recurrence rate of 8.9%. This percentage is slightly higher than in previous studies with shorter follow-up evaluation and higher than the percentages published previously by other investigators. The explanation may be a learning curve effect, thorough physical examination at follow-up assessment, or patient inclusion in the analysis on the intention-to-treat principle. The bilateral hernia percentage of 48% is higher than known from the literature to date. Therefore, contralateral examination at the initial presentation or during follow-up evaluation seems indicated.

Disclosures

Alexandra Brandt-Kerkhof, Marjolein van Mierlo, Niels Schep, Nondo Renken, and Laurents Stassen have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Corbitt JD. Laparoscopic herniorrhaphy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrequi ME, Navarrete J, Davis CJ, et al. Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy: techniques and controversies. Surg Clin North Am. 1993;73:513–527. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKernan JB, Laws HL. Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias using a totally extraperitoneal prosthetic approach. Surg Endosc. 1993;7:26–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00591232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferzli GS, Massad A, Albert PJ. Extraperitoneal endoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Laparoendosc Surg. 1992;2:281–286. doi: 10.1089/lps.1992.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knook MT, Weidema WF, Stassen LP, van Steensel CJ. Endoscopic total extraperitoneal repair of primary and recurrent inguinal hernias. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:507–511. doi: 10.1007/s004649901023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knook MT, Weidema WF, Stassen LP, Boelhouwer RU, van Steensel CJ. Endoscopic totally extraperitoneal repair of bilateral inguinal hernias. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1312–1316. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Memon MA, Coper NJ, Memon B, Memon MI, Abrams KR. Metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials comparing open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1479–1492. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons MP, de Lange D, Beets GL, van Geldere D, Heij HA, Go PM. The “Inguinal Hernia” guideline of the Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde. Ned Tijdschr Geneesk. 2003;147:2111–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Guidance on the use of inguinal hernia, London. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA083/guidance/.pdf. Retrieved September 2004

- 10.Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Joasson O, Fitzgibbons R, Jr, Dunlop D, Gibbs J, Reda D, Henderson W. Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N Eng J Med. 2004;350:1819–1827. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards CC, II, Bailey RW. Laparoscopic hernia repair: the learning curve. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10:149–153. doi: 10.1097/00019509-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medical Research Council Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Trial Group Cost-utility analysis of open versus laparoscopic groin hernia repair: results from a multicentre randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg. 2001;88:653–661. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferzli GS, Shapiro K, De Turris SV, Sayad P, Patel S, Graham A, Chaudry G. Totally extraperitoneal (TEP) hernia repair after an original TEP: is it safe, and is it even possible? Surg Endosc. 2004;18:526–528. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czechowski A, Schafmaer A. TAPP versus TEP: a retrospective analysis 5 years after laparoscopic transperitoneal and total endoscopic extraperitoneal repair in inguinal and femoral hernia. Chirurg. 2003;74:1143. doi: 10.1007/s00104-003-0738-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamb AD, Robson AJ, Nixon SJ. Recurrence after totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic repair: implications for operative technique and surgical training. Surgeon. 2006;4:299–307. doi: 10.1016/S1479-666X(06)80007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid T, Fortelny R, Hollinsky C, Kawji R, Steiner E, Pernthaler H, Függer R, Scheyer M, Pokorny H, Klingler Recurrence and complications after laparoscopic versus open inguinal hernia repair: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. Hernia. 2008;12:385–389. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staarink M, van Veen RN, Hop WC, Wiedema WF. A 10-year follow-up study on endoscopic total extraperitoneal repair of primary and recurrent inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1803–1806. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liem MSL, van der Graaf Y, van Steensel CJ, Boelhouwer RU, Clevers GJ, Meyer WS, Stassen LPS, Vente JP, Weidema WF, Schrijvers AJP, van Vroonhoven ThJMV. Comparison of conventional anterior surgery and laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1541–1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705293362201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Veen RN, Wijsmuller AR, Vrijland WW, Hop WC, Lange JF, Jeekel J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of nonmesh versus mesh repair of primary inguinal hernia. Br J Surg. 2007;94:506–510. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liem MSL, van Steensel CJ, Boelhouwer RU, Weidema WF, Clevers GJ, Meijer WS, Vente JP, de Vries LS, van Vroonhoven TJMV. The learning curve for totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J of Surg. 1996;171:281–285. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89569-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junge K, Rosch R, Klinge U, Schwab R, Peiper Ch, Binnebosel M, Schenten F, Schumpelick V. Risk factors related to recurrence in inguinal hernia repair: a retrospective analysis. Hernia. 2006;10:309–315. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorensen LT, Frijs E, Jorgensen T, Vennits B, Andersen BR, Rasmussen GI, Kjaergaard J. Smoking is a risk factor for recurrence of groin hernia. World J Surg. 2002;26:397–400. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]