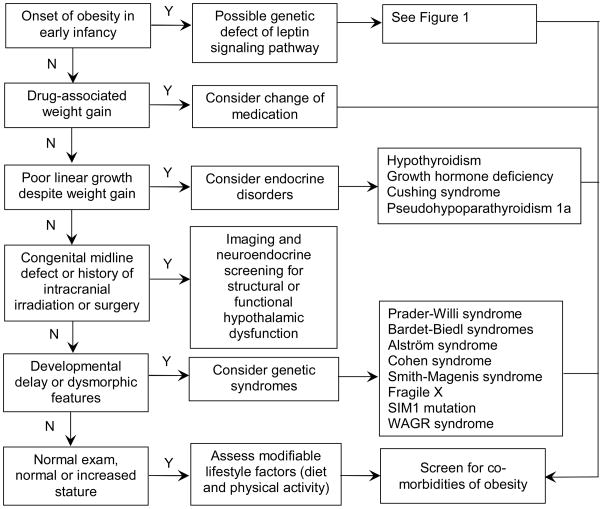

Figure 2. Recommended evaluation of childhood-onset obesity.

The clinical history and examination of the patient should guide the care provider in forming a differential diagnosis. Onset of marked obesity during early infancy raises the suspicion for function-altering genetic mutations affecting the leptin signalling pathway, but these are exceedingly rare conditions, with the most common, melanocortin-4 receptor defects, comprising <5% of children with early-onset obesity.130 When evaluating new onset of excessive weight gain, potential side effect from a recently initiated medication should be taken into consideration, as weight gain may be associated with administration of insulin or insulin secretagogues, glucocorticoids, hormonal contraceptives (e.g., depot medroxyprogesterone acetate), psychotropic medications (including atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone), mood stabilizers (e.g. lithium), tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, imipramine, and nortriptyline), and anticonvulsants (e.g., valproic acid, gabapentin, and carbamazepine)), antihypertensives (e.g., propranolol and clonidine), and antihistamines.139 In patients with decreased growth velocity despite continued weight gain, an endocrinopathy should be considered; measurement of TSH and free T4, and referral to a paediatric endocrinologist are recommended. All patients, regardless of the aetiology of obesity, should be assessed for modifiable lifestyle factors, including physical activity and diet, and screened for complications of obesity, including measurement of fasting lipids, fasting glucose, and alanine amino transferase. If fasting glucose is 100 – 126 mg/dL, an oral glucose tolerance test is recommended. Screening for vitamin D and iron deficiency should also be considered.