Abstract

By comparing the results from a hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) method (SORCI+Q//B3LYP/6-31G*:Amber) between the vertebrate (bovine) and invertebrate (squid) visual pigments, the mechanism of molecular rearrangements, energy storage and origin of the bathochromic shift accompanying the transformation of rhodopsin to bathorhodopsin have been evaluated. The analysis reveals that, in the presence of an unrelaxed binding site, bathorhodopsin was found to carry almost 27 kcal·mol−1 energy in both the visual pigments and absorb (λmax) at 528 nm in bovine and 554 nm in squid. However, when the residues within 4.0Å radius of the retinal are relaxed during the isomerization event, almost ~16 kcal·mol−1 energy is lost in squid compared to only ~8 kcal·mol−1 in bovine. Loss of larger amount of energy in squid is attributed to the presence of a flexible binding site compared to a rigid binding site in bovine. Structure of the squid bathorhodopsin is characterized by formation of a direct H-bond between the Schiff base and Asn87.

Rhodopsin, the photoreceptor responsible for twilight vision in the vertebrate and invertebrate species, belongs to the family of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), the largest family of cell surface receptors, with a known X-ray structure. It is composed of seven-transmembrane (TM7) α-helices and contains the 11-cis-retinal chromophore attached to the ε-amino group of lysine residue through a protonated Schiff base (PSB11) linkage. Excitation by the visible light initiates 11-cis to 11-trans isomerization leading to the formation of bathorhodopsin.1

In bovine (vertebrate) rhodopsin, which absorbs at 498 nm (57.4 kcal·mol−1), its batho intermediate was found to carry 35 ± 2 kcal·mol−1 of energy and peak at ~535 nm.2–4 The energy stored is used to drive the protein through the visual cycle. Increased charge separation between PSBT and counterion (Glu113) upon photoisomerization5 and conformational distortion of the strained photointermediate6 have been proposed as the major sources of energy storage; a 40 to 60% ratio of the two mechanisms has been estimated based on semi-empirical calculations in the past.7

Gascon et al. used the ONIOM QM/MM-EE scheme at B3LYP/6-31G*:Amber//TDB3LYP level of theory to predict a batho model that carries 34.1 kcal·mol−1 and absorbs at 485 nm.8 Andruniow et al. used the multiconfigurational quantum chemical (CASPT2//CASSCF/6-31G*:Amber) treatment to predict a batho model that carries 26.0 kcal·mol−1 and absorbs at 502 nm.9 Both the calculations ruled out any dominant role for charge separation between the PSBR and counterion in the energy storage process. Instead the former attributed 50% of the energy to be stored in the form of electrostatic contribution,8 while the latter attributed the same amount to conformational distortion,9 thus supporting the conclusions originally reached by Röhrig et al.10 Notice that, irrespective of the method used, the calculations did not reproduce the red shift of ~45 nm that serves as the signature motif of bathorhodopsin.11

The X-ray structure of bovine bathorhodopsin became available around this time,12 allowing a quantitative assessment of these factors using high-level quantum mechanical studies. Schrieber et al. found an almost quantitative agreement with the spectra by calculating a red shift of 36 nm (492→528 nm), but surprisingly only 16.3 kcal·mol−1 was accounted for in that study.13 Khrenova et al. modeled the ground state reaction route from rho to batho and calculated only 16.0 kcal·mol−1 and 4 nm red shift (515→519 nm).14 By using 9-demethyl analogue, Sugihara et al. found Tyr191 and Tyr268 residues to stabilize the batho geometry,15 while Sekharan et al. showed wat2a and wat2b to contribute a meager 2 kcal·mol−1 towards the energy storage process.16 Despite numerous efforts from many researchers, theoretical prediction of a batho model that accounts for both the energy storage and bathochromic shift has so far remained elusive.

Recently, X-ray structure of the squid rhodopsin has become available17,18 and it has opened the way for studying the primary event in vision in an invertebrate. Interestingly, most of the earlier studies on invertebrate visual pigments have been performed on octopus rhodopsin19 and only few studies were performed on squid rhodopsin, which showed the batho intermediate to peak at 550 nm, slightly red shifted than its vertebrate counterpart.20

Since the mechanism of isomerization is an efficient, ultrafast and stereoselective reaction, it is usually assumed that relaxation of the protein environment cannot occur within the experimentally observed 200 fs time frame.21 Furthermore, it is generally agreed that activation of rhodopsin by light and/or heat should follow the same molecular route22 and that the isomerization coordinate is mainly coupled to the vibrational modes of the retinal.23 These assumptions lead to the exclusion of protein relaxation in the ensuing QM/MM calculations of the primary event in visual24 and archaeal rhodopsins.25

In the present theoretical study, by taking the bovine and squid rhodopsin structures as templates, we try to gain insights into the structural rearrangements, energy uptake and change in electronic spectra during the cis-trans isomerisation process. We show that geometry relaxation of protein environment in the vicinity of chromophore is essential for evaluating the photoisomerization process and the accompanying spectral and energy changes.

We have attempted to obtain the structure of bathorhodopsin from bovine and squid rhodopsins using two sets of calculations that differ in the treatment of the binding site. To begin with, the QM/MM optimized structures of wild-type bovine and squid rhodopsins are taken from ref 26a, 26b. We first generate the relaxed intermediate structures along the ground-state minimum energy path (S0-MEP), subject to the constraints of a fixed dihedral angle ϕ(C11=C12) about the isomerizing double bond. Geometry optimization is performed at the ONIOM-EE (B3LYP/6-31G*:Amber) level of theory implemented in Gaussian0327 by incrementally rotating the C11=C12 dihedral angle from −17° in PSB11 (wild-type) to −180°. The resulting chromophores are then relaxed without any constraints in the dihedral angle yielding PSBT-FP, which corresponds to the structure obtained in the presence of a fixed protein (FP) environment and PSBT-4ÅR, which corresponds to the structure obtained when the residues within 4.0 Å radius (4ÅR) of any atom from the retinal are relaxed during the isomerization event. Such an approach allows us to gain insights into the influence of local environmental perturbations in the formation of bathorhodopsin. To obtain the electronic spectra, ab initio multireference QM/MM calculations were performed on the resulting structures using the spectroscopy oriented configuration interaction (SORCI+Q)28 method with 6-31G* basis using the ORCA 2.6.19 program.

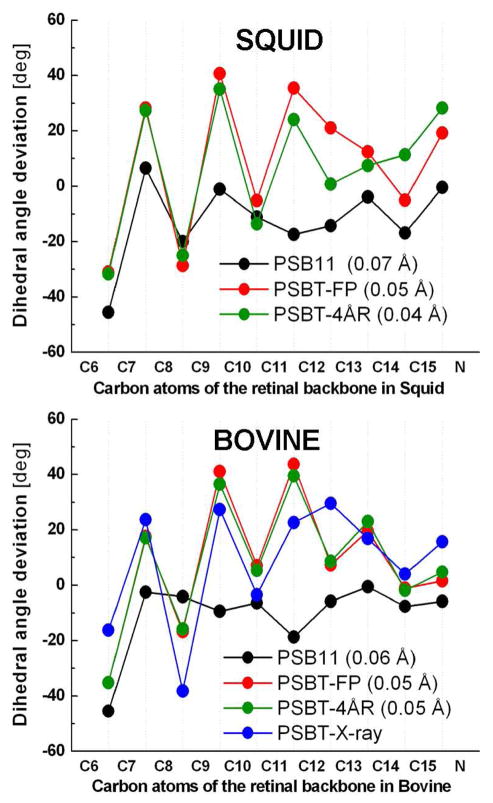

In the absence of X-ray structure, the calculated geometric parameters of invertebrate bathorhodopsin are also validated against that of its vertebrate counterpart resolved at 2.6 Å resolution (PDB:2G87).12 Average bond length alternation (BLA) of the C5-N moiety (Figure 2), which is defined as the average of the bond lengths of single bonds minus that of double bonds, is only slightly different for PSB11 in both the pigments. Irrespective of the difference in the protein environments, the PSBT-FP geometry of bathorhodopsin contains a distorted chromophore with BLA of 0.05 Å. When the residues within 4.0 Å radius are relaxed, distortion of PSBT-4ÅR geometry increases and BLA decreases to 0.04 Å in squid but not in bovine, which indicates that significant perturbation of the local environment has taken place in the invertebrate pigment (Figure 2, top).

Figure 2.

Dihedral angle deviations (top) along the conjugated carbon chain of the retinal backbone atoms of bovine (bottom) and squid (top) rhodopsins. The deviations are from either cis (0°) or the trans (180°) configuration. Refer text for abbreviations. Values in parentheses indicate the bond length alternation of the chromophores discussed in this study. PSBT-X-ray in blue refers to the 2.6 Å X-ray structure of bovine bathorhodopsin (PDB code: 2G87)

In the case of bovine bathorhodopsin, compared to the X-ray structure, the calculated bond angles differ by ~5° for the odd numbered carbon positions. Except for the terminal C15=N bond, the dihedral angle deviations (Figure 2, bottom) of all the double bonds are strongly twisted, from ~20° (C7=C8 bond), to almost 40° for (C9=C10 and C11=C12 bonds) in both pigments consistent with the resonance Raman29 and NMR30 spectroscopic measurements. Especially, a large twist (~20°) about the C13=C14 bond in bovine is found to be in good agreement with the X-ray structure.12 A discrepancy is noted for the C12–C13 bond, which is found to be twisted in the X-ray structure. All the single bonds remain almost planar in good agreement with structures obtained from the related MEP calculations8,9 and molecular dynamics simulations.10,31 It is generally agreed that twisting of the chromophore in bovine rhodopsin is due to the presence of an H-bonding Glu113 counterion, which anchors the proton at the SB terminal and induces stiffness into the retinal backbone.32–34 Structural manifestation of the presence of a non-H-bond Glu180 counterion near the isomerizing C11=C12 in squid rhodopsin is seen in the dihedral angle deviations from C11 to SBN+ moiety.

In bovine rhodopsin, position of the Glu113 counterion remains almost unperturbed during the isomerization process, indicating a strong H-bonding strength for the SB.35 In contrast, when the binding site is relaxed, distance between the SB and counterion (Glu180) in squid rhodopsin increases by 0.41 Å (4.29 Å to 4.70 Å). Increase in charge-separation by ~0.4 Å can be compared to the experimentally determined distance between the SB and the counterion (Glu113) in bovine bathorhodopsin, which increases by ~0.45 Å, from 3.45 to 3.88 Å (chain A) or 3.28 to 3.74 Å (chain B), respectively.12 Also, Asn87 is drawn closer by almost 1.0 Å (from 3.93 Å to 2.96 Å) to form a strong H-bond with SB and Tyr111 by 0.16 Å (from 3.41 Å to 3.25 Å). This observation strongly argues against the popular notion that the protein structure remains frozen during the isomerization event and that the X-ray structure of bathorhodopsin should correspond to the relaxed protein geometry in the vicinity of the chromophore.

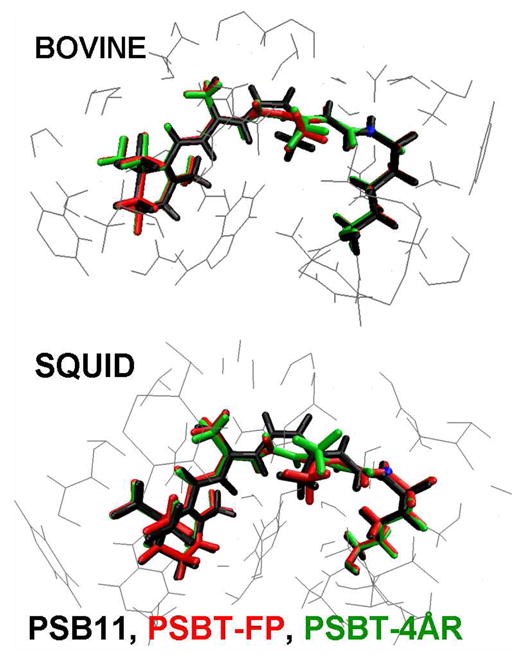

Perusal of Figure 3 reveals that one end of the retinal tether is held fixed by the β-ionone ring in the hydrophobic cleft of the binding site and the other end is bound to the protein via the SB-lysine linkage. As a consequence the C11=C12 bond undergoes a clockwise rotation from −17° in PSB11 to −136°/−145° in PSBT-FP geometry and to −141°/−156° in PSBT-4ÅR geometry of bovine/squid bathorhodopsins. Experimental evidence for the distorted 11-trans-geometry is seen in the hydrogen out-of-plane (HOOP) wagging modes at C11 and C12 positions36 as the chromophore adopts a corkscrew-like structure with a right-hand screw sense.13 As a result, the cis link is shifted from C11=C12 bond in rhodopsin to C15=N bond in bathorhodopsin as originally proposed by Warshel37 and recently validated by molecular dynamics simulations.38 Therefore, irrespective of the change in position of the counterion, the chromophore should undergo isomerization via the “bicycle-pedal motion” in both the visual pigments.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the QM/MM optimized structures of bovine and squid rhodopsin and bathorhodopsins. Refer text for abbreviations

Comparison of the optimized geometries in vacuo shows the PSB11 to be less stable than the trans-isomer by 5.64 kcal·mol−1, as a consequence of steric crowding around the cis-configurated C11=C12 bond. However, results from the QM/MM calculation of the visual pigment reveal a different picture. Perusal of the QM and MM energies (see the Supporting Information) show that, PSBT suffers significantly more destabilization that raises its energy and reverses the stability above that of the cis-isomer. As a consequence, PSBT-FP model of squid bathorhodopsin was found to carry 27.60 kcal·mol−1 energy out of which, 14.03 kcal·mol−1 or 51% of the energy is stored in the form of conformational distortion of the chromophore and the remaining 13.57 kcal·mol−1 (49%) of energy stems from the electrostatic and polarization effect of the fixed protein environment. Similarly, the PSBT-FP model of bovine bathorhodopsin stores almost the same amount of energy (26.10 kcal·mol−1) out of which, 19.78 kcal·mol−1 (75%) is attributed to conformational distortion and only 6.32 kcal·mol−1 (25%) is due to the electrostatic and polarization effect. The calculated value of 26.10 kcal·mol−1 is in excellent agreement with the Arrhenius activation energy23 of ~25 kcal·mol−1 and also with the photocalorimetric measurements2,3 of 35 ± 2 kcal·mol−1 for bovine rhodopsin.

However, the situation changes dramatically, more so in the case of squid rhodopsin when the immediate environment is relaxed during the isomerization process. In other words, PSBT-4ÅR model of squid bathorhodopsin stores only 11.08 kcal·mol−1 of energy out of which, 1.99 kcal·mol−1 or 17% is stored in the form of geometric distortion and 9.08 kcal·mol−1 or 83% is retained via electrostatic and polarization effect. In contrast, the PSBT-4ÅR model of bovine bathorhodopsin stores almost 19.45 kcal·mol−1 of energy out of which, 15.58 kcal·mol−1 or 80% is retained through geometric distortion and 3.87 kcal·mol−1 or 20% via electrostatic and polarization effect. Apparently, difference in the loss of substantial amount of energy is attributed to the presence of flexible binding site in squid (due to non-H-bonding Glu180 counterion) compared to a rigid binding site in bovine rhodopsin (due to H-bonding Glu113 counterion).39

Because Glu181 occupies the position corresponding to Glu180 counterion in squid, the same set of MEP calculations were also performed in the presence of a charged Glu181 residue in bovine rhodopsin. Although Glu181 was postulated to be involved in the counterion-switch mechanism,40 we find no role for a charged Glu181 residue in the energy storage process as long as the binding site remains unrelaxed, in agreement with the findings from Tomasello et al.41 In presence of a charged Glu181 residue in bovine rhodopsin the energy stored is reduced by 3 kcal·mol−1, which indicates that Glu180 may have mediated the energy storage process in squid bathorhodopsin (see the potential energy curve around the ϕ(C11=C12) bond in the Supporting Information). Therefore, we suggest that, for optimum storage of the photonic energy required for driving the visual cycle, it is advantageous for the protein environment to remain almost unrelaxed during the photochemical event.

Now turning our attention to the UV/Vis spectral data and how they develop as a function of the structural changes the chromophores undergo, we take a look at the SORCI+Q calculated ground- and the excited-state properties given in the Table 1. It has already been shown that, both the 11-cis and 11-trans chromophores absorb at around 610 nm in vacuo and the difference between the calculated λmax of PSB11 and the PSBT chromophores is very small (~10 nm), probably too small to be detected experimentally.42–45

Table 1.

The calculated SORCI+Q first vertical excited state absorption wavelengths (λ) in nm, oscillator (f) and rotatory (R) strengths in au and difference in the ground-(S0) and excited state (S1) dipole moments (Δμ) of the PSB11, PSBT-FP, PSBT-4ÅR chromophores in the gas-phase (QM-none) and protein (QM/MM) environments. Experimental values for bovine: PSB11 = 506 nm; PSBT = 543 nm; and squid: PSB11 = 493 nm; PSBT = 550 nm are taken from reference 20c.

| PSBR | SORCI+Q//B3LYP/6-31G* First Vertical Excited State (S1→S0) Properties |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas phase (QM-none) |

Protein (QM/MM) |

||||||

| Bovine Rhodopsin and Bathorhodopsin | |||||||

| λ | f | R | λ | f | R | Δμ | |

| PSB11 | 616 | 1.20 | +0.09 | 495 | 1.40 | +0.21 | 12.1 |

| PSBT-FP | 657 | 1.31 | −0.98 | 528 | 1.43 | −0.83 | 12.7 |

| PSBT-4ÅR | 635 | 1.37 | −0.96 | 525 | 1.50 | −0.83 | 12.9 |

|

Squid Rhodopsin and Bathorhodopsin | |||||||

| PSB11 | 604 | 0.93 | +0.16 | 490 | 1.14 | +0.32 | 11.7 |

| PSBT-FP | 677 | 1.12 | −1.17 | 554 | 1.25 | −1.08 | 12.2 |

| PSBT-4ÅR | 649 | 1.29 | −0.76 | 543 | 1.39 | −0.72 | 12.7 |

In contrast, irrespective of the treatment of the binding site, geometric distortions accumulated during the isomerization event decreases the BLA and shifts the λmax from 616/604 nm to the red, 635/657 nm in bovine and 649/677 nm in squid. This indicates that origin of the bathochromic shift lies at geometric distortion of the PSBT chromophore. Interaction of the chromophore with counterion induces a strong blue-shift of ~100 nm and shifts the calculated λmax very close to the experimental values; 528/525 nm in bovine4,46 and 554/543 nm in squid bathorhodopsins.20 Effect of the counterion is conceivable, as the excited state charge density is shifted against the charge of the counterion. This shift is also the reason for the change in the dipole moment of the S1 state relative to the S0 state, which is calculated to be ~12.0 D in good agreement with the experimental observations by Mathies et al (12.0 ± 2.0 D).47 Compared to the strong blue-shift of the counterion, the spectral shifts from the neutral residues are negligible.48 Especially, increase in oscillator strength of the batho intermediate found in the experimental observations7a is also reproduced in the QM/MM calculations.

Absolute sense of twist of the corkscrew-like structure of the bathorhodopsin chromophore is evaluated by calculating the rotatory strengths of before and after isomerization. It is shown that, out-of-plane distortion about the C11=C12 (negative) and C12—C13 (positive) bonds impart a positive helicity on the rhodopsin chromophore, yielding a positive rotatory strength (R) in both pigments.49 The calculated α-band and R-value of 495 nm and +0.21 au for bovine and 490 nm and +0.32 au for squid agree both in sign and magnitude with the experimental values.50 In bathorhodopsin, the band inverts in sign and magnitude with the R-value of −0.83 au in bovine and −1.08 au in squid. Both the sign inversion and marked increase in the spectral gap of ~30 nm in bovine and ~50 nm in squid are already seen in their respective gas-phase spectra and are only slightly increased by their corresponding protein environments. In particular, the small blue shift between the two rhodopsin pigments is attributed to the increase in BLA, from ~0.06 Å in bovine to ~0.07 Å in squid,26,39 and the small red shift between the bathorhodopsin pigments can be traced back to the decrease in BLA from 0.05 Å in bovine to 0.04 Å in squid (see Figure 2).

In conclusion, by taking the bovine and squid rhodopsin structures as templates, we have tried to gain insights into the structural rearrangements, energy uptake and change in electronic spectra during the cis-trans isomerisation process. The QM/MM calculated models of bathorhodopsin explains the consequence of configurational change in the first step of visual excitation and reproduces the main experimental observations in both the vertebrate and invertebrate pigments. From the evidence gathered, it is proposed that, similar to bovine rhodopsin, squid rhodopsin may also isomerize via the “bicycle-pedal motion” pathway. Thus organisms everywhere may tend to gravitate towards common solution even in an apparatus as intriguing as an eye.

Supplementary Material

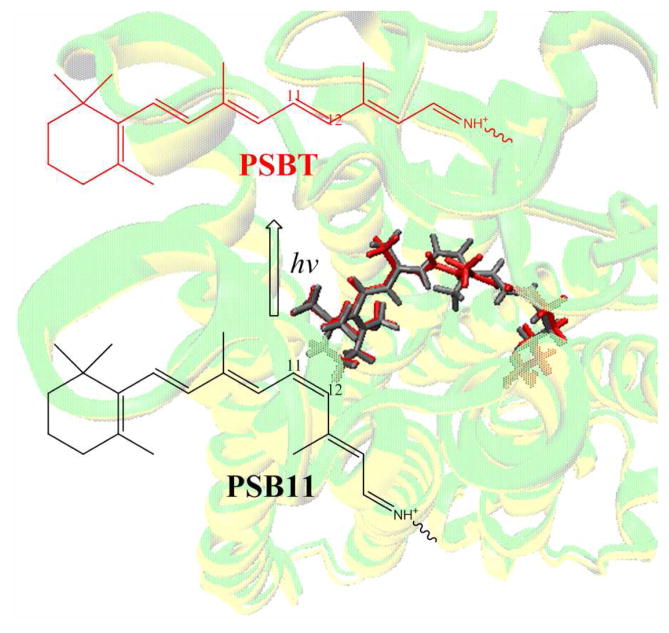

Figure 1.

Photoisomerization of the protonated Schiff base of 11-cis-retinal chromophore (PSB11) to 11-trans-retinal chromophore (PSBT). Also shown in the background are the PSB11 (black) and PSBT (red) chromophores embedded into the seven-transmembrane (TM7) α-helices of squid rhodopsin (yellow) and bathorhodopsin (green)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Profs. R. R. Birge, J. Gascon and A. Cooper for the valuable discussions. The work at Emory is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01EY016400-04) and at Kyoto by a Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) grant in the Area of High Performance Computing for Multiscale and Multiphysics Phenomena JST.

Footnotes

Model building, cartesian coordinates of retinal models are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.a) Smith SO, Courtin J, De Groot H, Gebhard R, Lugtenburg J. Biochemistry. 2001;30:7409–7415. doi: 10.1021/bi00244a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lewis JW, Fan GB, Sheves M, Szundi I, Kliger DS. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10024–10029. doi: 10.1021/ja010724q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper A. Nature. 1979;282:531–533. doi: 10.1038/282531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schick GA, Cooper TM, Holloway RA, Murray LP, Birge RR. Biochemistry. 1987;26:2556–2562. doi: 10.1021/bi00383a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandori H, Shichida Y, Yoshizawa T. Biophys J. 1989;56:453–457. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82692-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honig B, Ebrey T, Callender RH, Dinur U, Ottolenghi M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:2503–2507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.6.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warshel A, Barboy N. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:1469–1476. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Birge RR, Einterz CM, Knapp HM, Murray LP. Biophys J. 1988;53:367–385. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83114-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tallent JR, Hyde EW, Findsen LA, Fox GC, Birge RR. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1581–1592. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gascon JA, Batista VS. Biophys J. 2004;87:2931–2941. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.048264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andruniow T, Ferrè N, Olivucci M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17908–17913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407997101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Röhrig UF, Guidoni L, Laio A, Frank I, Rothlisberger U. J Amer Chem Soc. 2004;126:15328–15329. doi: 10.1021/ja048265r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Einterz CM, Lewis JW, Kliger DS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3699–3703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamichi H, Okada T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4270–4273. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber H, Sugihara M, Okada T, Buss V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4274–4277. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khrenova MG, Bochenkova AV, Nemukhin AV. Proteins. 2009;78:614–622. doi: 10.1002/prot.22590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugihara M, Buss V. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13733–13735. doi: 10.1021/bi801986p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekharan S. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85:517–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimamura T, et al. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17753–17756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800040200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami M, Kouyama T. Nature. 2008;453:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature06925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuda M, Tokunaga F, Ebrey TG, Yue KT, Marque J, Eisentein L. Nature. 1980;287:461–462. doi: 10.1038/287461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Hubbard R, StGeorge RCC. J Gen Physiol. 1958;41:501–528. doi: 10.1085/jgp.41.3.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hara TT, Hara R, Takeuchi J. Nature. 1967;214:572–573. doi: 10.1038/214572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sulkes M, Lewis A, Marcus MA. Biochemistry. 1978;17:4712–4722. doi: 10.1021/bi00615a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Shichida Y, Kobayashi T, Ohtani H, Yoshizawa T, Nagakura S. Photochem Photobiol. 1978;27:335–341. [Google Scholar]; e) Birge RR, Hubbard LM. Biophys J. 1981;34:517–534. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84865-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kukura P, McCamant DW, Yoon S, Wandschnedier DB, Mathies RA. Science. 2005;310:1006–1009. doi: 10.1126/science.1118379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ala-lauria P, Donner C, Koskelainen A. Biophys J. 2004;86:3653. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin SW, Groesbeek M, van der Hoef I, Verdegem P, Lugtenburg J, Mathies RA. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:2787–2806. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polli D, et al. Nature. 2010;467:440–443. doi: 10.1038/nature09346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altoè P, Cembran A, Olivucci M, Garavelli M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20172–20177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Altun A, Yokoyama S, Morokuma S. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:6814–6827. doi: 10.1021/jp709730b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sekharan S, Altun A, Morokuma K. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:1744. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frisch MJ, et al. GAUSSIAN. Gaussian Inc; Pittsburgh PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neese FA. J Chem Phys. 2003;119:9428–9443. [Google Scholar]

- 29.a) Fransen MR, et al. Nature. 1976;260:726–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Eyring G, Mathies R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:33–37. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Eyring G, Curry B, Mathies R, Fransen R, Palings I, Lugtenburg J. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2410–2418. doi: 10.1021/bi00552a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kim JE, Pan D, Mathies RA. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5169–5175. doi: 10.1021/bi030026d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.a) Concistrè M, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10490–10491. doi: 10.1021/ja803801u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Gansmüller A, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:1350–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frutos LM, Andruniów T, Santoro F, Ferré N, Olivucci M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;2410–2418 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701732104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu RS, Asato AE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:259–263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vergdegem PJE, Bovee-Geurts PHM, de Grip WJ, Lugtenburg J, de Groot HJM. Biochemistry. 1998;38:11316. doi: 10.1021/bi983014e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugihara M, Hufen J, Buss V. Biochemistry. 2006;45:801–810. doi: 10.1021/bi0515624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ota T, Furutani Y, Terakita A, Yoshinori S, Kandori H. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2845–2851. doi: 10.1021/bi051937l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palings I, van den Berg EMM, Lugtenburg J, Mathies RA. Biochemistry. 1989;28:1498–1507. doi: 10.1021/bi00430a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warshel A. Nature. 1976;260:679–683. doi: 10.1038/260679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schapiro I, Weingart O, Buss V. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16–17. doi: 10.1021/ja805586z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sekharan S, Altun A, Morokuma K. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15856–15859. doi: 10.1021/ja105050p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.a) Yan ECY, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9262–9267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531970100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kusnetzow AK, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:941–946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yan ECY, et al. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10867–10876. doi: 10.1021/bi0400148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomasello G, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5172–5186. doi: 10.1021/ja808424b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wanko M, et al. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:3606–3615. doi: 10.1021/jp0463060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nielsen IB, Lammich L, Andersen LH. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:018304–018307. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.018304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sekharan S, Weingart O, Buss V. Biophys J. 2006;91:L07–L09. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffmann M, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:10808–10818. doi: 10.1021/ja062082i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spalink JD, Reynolds AH, Rentzepis PM, Sperling W, Applebury ML. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1887–189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.7.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathies RA, Styrer L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sekharan S, Sugihara M, Buss V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:269–271. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.a) Buss V, Kolster K, Terstegen F, Vahrenhost R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:1893–1895. [Google Scholar]; b) Fujimoto Y, Fishkin N, Pescitelli G, Decatur N, Berova N, Nakanishi K. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7294–7302. doi: 10.1021/ja020083e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.a) Horiuchi S, Tokunaga F, Yoshizawa T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;591:445–457. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shichida Y, Tokunaga F, Yoshizawa T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;504:413–430. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(78)90064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.