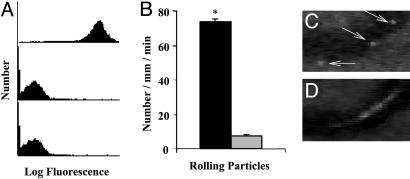

Fig. 4.

PSGL-1-conjugated PLA–PEG particles adhere to trauma-activated microvascular endothelium in vivo. (A) PLA–PEG particles, precoupled with either 19.ek.Fc (a recombinant PSGL-1 construct) or ek.Fc (negative control), were treated with a mAb to human PSGL-1 (KPL-1) or human P-selectin (HPDG2/3), washed, treated with an FITC-labeled polyclonal antibody, and analyzed by FACS. (Top) 19.ek.Fc-LEAPs treated with a mAb to PSGL-1 (KPL-1). (Middle) 19.ek.Fc-LEAPs treated with a mAb to P-selectin (isotype-matched control mAb). (Bottom) ek.Fc PLA–PEG particles treated with a mAb to PSGL-1 (KPL-1). Results shown are typical of n = 2 separate experiments. (B) 19.ek.Fc or ek.Fc particles were injected into mice (2 × 107 per mouse), and the number of rolling particles was determined. A significantly greater number of rolling 19.ek.Fc-LEAPs was observed compared to ek.Fc PLA–PEG particles. *, P < 0.05. (C and D) A segment of a postcapillary venule from a typical experiment is shown. (C) Three images were taken 1 s apart and superimposed to generate the composite image. The white sphere (marked by the arrows) is a 19.ek.Fc-LEAP rolling along the wall of the venule. (D) Two images were taken 1/30th of a second apart and superimposed to generate the composite image. The white blur is a PLA–PEG particle(s) not interacting with the vessel wall.