Abstract

Oxidative stress has been shown to convert endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) from an NO-producing enzyme to an enzyme that generates superoxide, a process termed NOS uncoupling. This uncoupling of eNOS converts it to function as an NADPH oxidase with superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generation. eNOS uncoupling has been associated with many pathophysiologic conditions, such as heart failure, ischemia/reperfusion injury, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and diabetes. The mechanisms implicated in the uncoupling of eNOS include oxidation of the critical NOS cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin, depletion of l-arginine, and accumulation of methylarginines. All of these prior mechanisms of eNOS-derived reactive oxygen species formation occur primarily at the heme of the oxygenase domain and are blocked by heme blockers or the NOS inhibitor N-nitro-l-arginine methylester. Recently, we have identified another unique mechanism of redox regulation of eNOS through S-glutathionylation that was shown to be important in cell signaling and vascular disease. Herein, we briefly review the mechanisms of eNOS uncoupling as well as their interrelationships and the evidence for their importance in disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1769–1775.

Oxidative stress has been shown to be of critical importance in the pathogenesis of a wide variety of disease processes including heart attack, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, excitotoxic brain injury, neurodegenerative disease, and the broad spectrum of inflammatory disease (35). Oxidative stress occurs in cells and tissues because of overproduction of superoxide (•O2−) and its secondary oxidants that are formed from several sources, including NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (3, 35, 48, 56). In addition, under some conditions, nitric oxide synthase (NOS) can become a source of •O2− (15, 31, 36, 43, 49, 50). Moreover, nitric oxide (NO) produced from NOS can react with •O2− to generate the potent oxidant, peroxynitrite (ONOO−) (2, 46, 51, 54, 55).

Endothelial NOS (eNOS) is responsible for the enzymatic generation of NO within the endothelium. eNOS is a homodimeric heme-containing enzyme that converts l-arginine and oxygen to l-citrulline, NO, and water, using NADPH as a source of reducing equivalents (36). This process involves the calcium/calmodulin-regulated transfer of electrons from NADPH through a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)- and flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-containing reductase domain to the heme of the l-arginine–binding oxygenase domain, which also binds tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) (6, 30). In the absence of BH4, NO synthesis is abrogated, and instead, •O2− is generated (43, 50).

NO is involved in a number of roles within the endothelium, regulating vascular tone, vascular growth, platelet aggregation, and modulation of inflammation (23, 29, 32). As such, endothelial dysfunction produced by a decrease in bioavailable NO is a characteristic feature in many disease states, and one of the mechanisms underlying this dysfunction is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the vasculature (2, 35, 48). A general mechanism by which ROS elicit endothelial dysfunction is via the impairment of NO signaling due to the ROS-dependent inactivation of eNOS (10, 34, 53). Further, studies have shown that eNOS itself can also become a source of ROS, in a process termed eNOS uncoupling (25, 43, 49). Under normal circumstances, the oxidation of NADPH is tightly coupled to the production of NO by eNOS. However, when the oxidation of NADPH is uncoupled from the production of NO, eNOS generates •O2− and secondary ROS.

We provide a brief review of the mechanisms underlying eNOS uncoupling, with a special focus on the newly identified mechanism involving the S-glutathionylation of eNOS (8).

eNOS Uncoupling via BH4 Oxidation

BH4 is crucial for proper eNOS function and is involved in stabilizing NOS protein structure. It fosters dimer formation and stabilizes the formed dimer. The transfer of electrons to the heme is an interdomain transfer, from the reductase domain of one monomer to the oxygenase domain of the second monomer of the eNOS dimer (30). As such, the dimer stability provided by BH4 binding facilitates eNOS coupling. BH4 binding also shifts the spin state of the heme iron and modifies the heme redox potential, making the transfer of electrons from the reductase domain more efficient. The binding of oxygen is also affected by BH4. Moreover, BH4 is absolutely required for the correct and timely activation of oxygen necessary for catalytic activity. The catalytic cycle of eNOS involves two mono-oxygenation steps, each requiring the formation of a two-electron reduced iron-oxo species at the NOS heme (36). First, an electron is transferred from the reductase domain to the heme, forming the ferrous heme, which then binds oxygen. BH4 delivers one electron to the oxygen-bound ferrous heme iron, producing the iron-oxo species necessary for catalysis. The one-electron oxidized BH4 (the BH3• radical) is reduced by the reductase domain to regenerate BH4, and the catalytic cycle continues (47). In the absence of BH4, the oxygen-bound ferrous heme dissociates, producing •O2− and the ferric heme. Two-electron oxidized BH4, dihydrobiopterin (BH2), can bind to NOS but does not support NO formation; rather, when BH2 is bound, eNOS produces •O2− (44). Thus, when BH4 is oxidized and/or catabolized, eNOS will become uncoupled and produce •O2− instead of NO.

It has been demonstrated in vivo and in vitro that eNOS is uncoupled when BH4 is limiting. The mechanism leading to BH4 depletion is generally attributed to oxidation of BH4 by ROS and/or ONOO−, the product of the reaction of NO with •O2−. •O2− can oxidize the NOS-bound BH4, and supplementation with BH4 has been found to restore NOS activity (15, 41). The in vivo source of the ROS that may lead to BH4 depletion has been attributed to pathways including NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and the mitochondrial electron transfer chain (27, 35, 57). ONOO− does rapidly oxidize BH4; however, it can also irreversibly inactivate the NOS enzymes, likely by a direct reaction with the NOS heme, producing an inactive enzyme rather than an uncoupled enzyme (10, 37, 38).

The oxidation of BH4 can result in eNOS uncoupling by two mechanisms, by reducing the total biopterin pool or by increasing the BH2:BH4 ratio (37, 38, 43, 44). A two-electron oxidation of BH4 produces the quinoid form of BH2 (qBH2), which can either rearrange to produce BH2 or decompose to form dihydropterin. Dihydropterin is subject to catabolism, and thus, oxidation of BH4 can result in a decrease in the total biopterin pool. BH2 can be recycled back to BH4 by the action of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), and this enzyme has been shown to be critical in the regulation of the BH2:BH4 ratio in endothelial cells (13).

eNOS Uncoupling via l-Arginine Depletion or Increase in Methylarginines

It has been well established that accumulation of methylarginines is associated with an increase in ROS production (24, 39, 40). This has also been identified in patient populations demonstrating endothelial dysfunction (5). Moreover, the activities of both the enzymes responsible for formation of methylarginines and the enzymes responsible for clearance of methylarginines (dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase) have been shown to be positively and negatively regulated by changes in the redox environment, respectively (5, 16). Accordingly, oxidative stress can lead to the accumulation of methylarginines. Moreover, it has been shown that the accumulation of methylarginines in endothelial cells to the levels found in pathophysiologic settings can reach the concentrations necessary to significantly inhibit eNOS activity (7).

Methylarginines inhibit NO generation by competitive inhibition, competing with the substrate l-arginine for the catalytic binding site. Additionally, it has been shown that the binding of methylarginines, in addition to inhibiting NO formation, actually stimulates the production of •O2− for the NOS enzymes (14). As such, binding of methylarginines produces an uncoupled NOS enzyme. Thus, ROS can lead to the accumulation of methylarginines, which in turn uncouples eNOS, producing positive feedback generating yet more ROS. However, this mechanism requires some initial ROS insult, and it is unclear whether the increase in methylarginines is a cause or effect, that is, does the accumulation of methylarginines trigger increased ROS or does the increased ROS formation cause the increase in methylarginines.

eNOS Uncoupling via S-Glutathionylation

In our recent report, we showed for the first time that S-glutathionylation of eNOS reversibly uncouples eNOS (8). It is clear that NOS dysfunction occurs in diseases associated with oxidative stress; however, supplementation with BH4 and/or l-arginine is insufficient to completely restore NOS activity in all cases (15). Thus, we hypothesized that another mechanism by which eNOS activity is affected must exist. It was known that protein thiols are involved in the regulation of NOS function; however, the mechanism by which this regulation occurred was not fully delineated. S-Glutathionylation is a posttranslational modification in which a glutathione tripeptide is reversibly bound to the protein via the formation of a disulfide bond with a protein thiol. This protein modification is involved in cellular signaling and it is thought to play a role in cellular adaptation to oxidative stress. Under oxidative stress, S-glutathionylation occurs via a number of mechanisms, including thiol–disulfide exchange with oxidized glutathione, reaction of oxidant-induced protein thiyl radicals with reduced glutathione, or reaction of a nitrosothiol (on either the glutathione or the protein) with another thiol. Thus, we hypothesized that oxidative stress could alter eNOS activity through S-glutathionylation (8).

This S-glutathionylation–directed uncoupling is unique among the eNOS uncoupling mechanisms in that the resultant •O2− generation is from the reductase domain. Two cysteine residues (Cys689 and Cys908) that are highly conserved within the NOS family of proteins are S-glutathionylated, both in vitro and in vivo. These two cysteines are critical for normal eNOS function, and when these residues are modified, the enzyme produces •O2− and this ROS production is not inhibited by N-nitro-l-arginine methylester (L-NAME) or by removal of calcium. We showed that eNOS S-glutathionylation in endothelial cells uncouples eNOS and this uncoupling is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Additionally, vessels treated with 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU), which increases the intracellular concentration of oxidized glutathione, exhibited both eNOS S-glutathionylation and endothelial dysfunction. Moreover, in vessels from spontaneously hypertensive rats, which have impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation, eNOS S-glutathionylation is increased, and this observed eNOS S-glutathionylation and the endothelial dysfunction of these vessels are reversed by addition of thiol-specific reducing agents. Thus, S-glutathionylation modulates endothelial function and vasodilation (8). Induction of eNOS uncoupling by S-glutathionylation switches eNOS from NO production to •O2− generation, with concomitant loss of endothelial-mediated vasodilation contributing to vascular constriction, which can lead to hypertensive cardiovascular disease (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Summary of physiological action of eNOS S-glutathionylation. eNOS present in endothelial cells, indicated by the green coloration, generates NO in the vasculature, which is known to induce vasodilation. When eNOS is S-gutathionylated, indicated by the yellow-colored portion of the endothelium (provided from immunohistology), the enzyme switches to produce superoxide (depicted as white bilobed spheres) instead of NO (blue/white bilobed spheres), which leads to vasoconstriction. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Mechanisms of S-Glutathionylation

Several mechanisms can lead to protein S-glutathionylation. Cysteines can be attacked by ROS to form thiyl radicals that in turn react with glutathione (GSH). Alternatively, protein thiols can be glutathionylated by oxidized glutathione (GSSG) through disulfide exchange (4, 17–19). Human eNOS (heNOS) contains 29 cysteines, 27 of which are conserved in all known mammals, and prior reports indicate (20–22) that NOS requires reducing agents, such as dithiothreitol, cysteine, or GSH, to promote NO production and maintain enzyme stability. We observed in vitro in the presence of GSSG that heNOS S-glutathionylation occurs. Thus, it is clear that eNOS possesses redox-sensitive thiols that are readily S-glutathionylated with profound modulation of the function of this critical enzyme. Protein thiols are of vital importance in redox signaling and regulation (4, 17–19). They maintain correct folding and tertiary protein structure and serve as redox sensors. At normal physiological pH, protein thiols are in the reduced state and are difficult to oxidize because of their protonation. However, the local electrostatic environments of some protein thiols can cause a shift to lower pKa, rendering these sites more susceptible to oxidation (4).

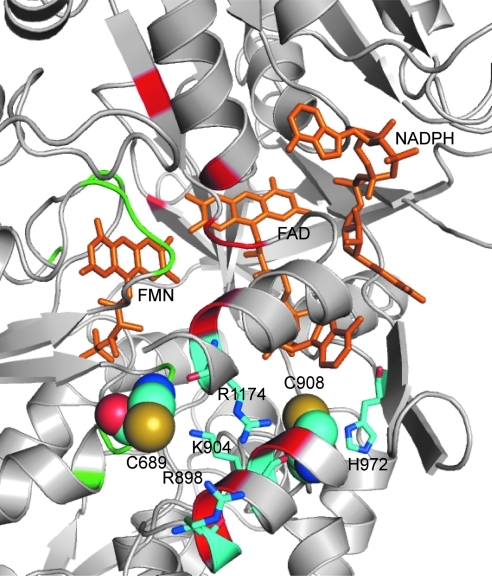

Although the X-ray crystal structure for the reductase domain of eNOS is not available, we predicted the three-dimensional structure of the heNOS reductase domain based on the reductase domain of rat neuronal NOS (1F20) using the Swiss Model First Approach Mode. This modeling showed that Cys689 and Cys908 are located on the domain surface surrounded by several positively charged residues. Cys689 is surrounded by Arg898, Lys904, and Arg1174. Cys908 is located in a pocket that contains His972, Arg1174, and the adenine ring of FAD (Fig. 2). Because of this positively charged environment, both Cys689 and Cys908 would likely be in the deprotonated states because of a lowered thiol pKa via electrostatic interactions, and as such these cysteine residues are predicted to be susceptible to oxidation by GSSG. However, other potential mechanisms, including the formation of protein thiyl radicals or protein nitrosothiols, followed by reaction with GSH can also occur. Indeed, the loss of eNOS activity in endothelial cells exposed to NO has been postulated to be due to thiol S-nitrosylation, which in turn reacts with vicinal or free thiols (including GSH) forming intramolecular or intermolecular disulfide bonds (42).

FIG. 2.

Molecular model of the human NOS reductase domain showing sites of S-glutathionylation. The three-dimensional structure of human NOS reductase was obtained by use of the Swiss-Model First Approach Mode. PyMOL was used to view and construct the three-dimensional structure. Cys689 and Cys908 are both located on the surface of reductase domain and surrounded by several positively charged residues, including Lys, Arg, and His. Cys689 is surrounded by Arg898, Lys904, and Arg1174. Cys908 is located in a pocket that contains His972, Arg1174, and the adenine ring of FAD. Because of this positively charged environment, both Cys689 and 908 are thought to be in deprotonated states with lower pKa and susceptible to oxidation by oxidized glutathione. Green and red regions represent residues at the interface of FMN and FAD domains, respectively. Cys689 is located at the FMN domain interface and Cys908 is near the FAD domain interface. (To see this illustration in color the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertonline.com/ars).

Glutathione is a tripeptide, consisting of glycine, cysteine, and glutamic acid, present in cells at 1–10 mM concentrations (9). S-Glutathionylation results in formation of a mixed disulfide bond between the reactive Cys-thiol and GSH. The additional bulky negatively charged GS group would alter the protein structure and function by both steric and electrostatic interactions. Our molecular modeling predicted that both Cys689 and Cys908 are located along the interface of the FAD- and FMN-binding domains, as such their modification would be predicted to alter FAD-FMN coupling, potentially by increasing their solvent accessibility (Fig. 2) (8). By exposing these flavins to the solvent environment, oxygen would be able to access and accept an electron from the reduced flavin, leading to •O2− formation, and by default decrease the electron transfer to heme, leading to eNOS uncoupling.

Potential Cellular Function of eNOS S-Glutathionylation

In response to oxidative stress, the formation of mixed disulfide bonds, such as S-glutathionylation, can functionally activate or inactivate enzymatic activity to combat or enhance dysfunction. For example, S-glutathionylation of creatine kinase inactivates the conversion of ADP to ATP, and this process can be reversed by GSH or DTT (33). In contrast, other enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinase, can be activated by S-glutathionylation (28). It has been well documented that NOS requires thiol-specific reducing agents for proper function, indicating that the enzyme contains cysteine residues that are critical for its function. Although S-glutathionylation induces a loss of NO synthesis with enzyme uncoupling, we observe that this process is reversible. As such, during oxidative stress, eNOS S-glutathionylation could function to prevent irreversible oxidative damage of the thiols critical for eNOS function, and with restoration of cellular reducing state, S-glutathionylation would be reversed, restoring proper eNOS function.

As described above, S-glutathionylation of eNOS uncouples the enzyme, leading to enhanced production of •O2−, which is a redox signaling molecule known to trigger cell proliferation, apoptosis, and senescence (9, 12). Therefore, S-glutathionylation of eNOS could play a role in switching the enzyme from the generation of one signaling molecule (NO) to the generation of a very different signaling molecule (•O2−). Thus, this protein modification provides a molecular redox-regulated switch for the control of cellular signaling. Indeed, we observed that with a shift of cellular redox state, induced by inhibition of glutathione reductase, eNOS S-glutathionylation occurs in endothelial cells with marked decrease in NO production and enhanced •O2− generation (8).

NO produced from NOS can react with •O2− to generate the potent oxidant, ONOO− (46, 51, 54, 55), and the abnormal cellular production of ONOO− has been linked with many diseases. As such, the decrease in NO production from S-glutathionylated heNOS may provide a regulatory mechanism to prevent irreversible oxidation in cells, caused by overproduction of ONOO−. Therefore, S-glutathionylation of eNOS has a pivotal role in switching the enzyme from NO to •O2− between generation, and this may control cellular redox signaling under oxidative stress.

Redox Regulation by Thioredoxin and Glutaredoxin

The identification of the S-glutathionylation–directed regulation of eNOS function opens a new avenue of potential enzymatic regulation of NO production. The sulfhydryl group of cysteine not only is important in maintaining protein structure, but also plays an important role as an antioxidant by reversible formation of disulfide or mixed disulfide bonds when it reacts with ROS. In cells, there are two major antioxidant systems, namely Thioredoxin (Trx) and Glutaredoxin (Grx), for maintaining the reduced state of protein thiols and cellular reducing environment after oxidative stress. The Trx system, consisting of Trx, NADPH, and Trx reductase, is a NADPH-dependent disulfide reductase that catalyzes disulfide reduction. The Grx system, consisting of Grx, GSH, glutathione reductase, and NADPH, is a GSH-dependent oxidoreductase that catalyzes the reduction of disulfides or mixed disulfides.

Numerous studies have shown that Trx exerts a protective effect against oxidative stress-induced damage in a number of tissues (45). Infusion of human Trx in an isolated rat heart subjected to ischemia/reperfusion protected the heart against reperfusion-induced arrhythmias (1). Overexpression of Trx in lung endothelial cells has been shown to prevent NO-induced reduction of NOS activity (52). For the Grx system, the results from mouse models with Grx1 knockout, as well as overexpression of Grx1 and Grx2, suggested that Grx exerts a cardioprotective effect through protein deglutathionylation after oxidative stress (11, 26). Therefore, the deglutathionylation of eNOS by Grx could provide a potential mechanism of enzyme-directed redox regulation of eNOS function, which could more specifically modulate cardiovascular function and disease.

Uniqueness of S-Glutathionylation–Induced Superoxide Generation

Classically, eNOS-derived •O2− generation is inhibited by the NOS inhibitor N-nitro-l-arginine and its methylester L-NAME. When the nitro-substituted arginine analog occupies the l-arginine binding site, the reduction of the heme iron by the reductase domain is inhibited, and as such the ferric heme does not bind oxygen and is thus incapable of promoting the production of •O2−. Conversely, although methylarginines inhibit NO generation from NOS (via competition with the substrate l-arginine), they enhance the reduction of the heme iron and as such enhance the generation of the NOS heme-derived •O2− (7, 14). Thus, classically, NOS-derived •O2− has been defined as detection of •O2− in cells and tissues that is sensitive to L-NAME inhibition but not to methylarginine inhibition.

We have shown that S-glutathionylation of critical thiols uncouples heNOS, and the resultant •O2− generation of S-glutathionylated eNOS is not suppressed by L-NAME or EGTA. As such, this eNOS uncoupling mechanism is different from that induced by lack of substrate l-arginine, increase in cellular methylarginines, or alteration in NOS-bound BH4. These previously described forms of uncoupling occur primarily at the oxygenase site and are regulated by Ca2+/calmodulin or blocked by inhibitors at the heme, whereas the •O2− generation induced by thiol modification is largely Ca2+/calmodulin and heme independent. Thus, it is impossible to definitively distinguish between •O2− from S-glutathiolated eNOS and other •O2− sources using the aforementioned combination of l-arginine analog insensitivity/sensitivity. This vascular •O2− generation would be inhibited by flavin-based inhibitors such as diphenyleneiodonium in a manner similar to that observed for vascular NADPH oxidase and might only be distinguished by its sensitivity to thiol-reducing agents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the oxidant stress that occurs in many diseases including heart attack, stroke, diabetes, and cancer can trigger a newly discovered molecular switch, S-glutathionylation, which alters the function of the critical cell-signaling enzyme eNOS. S-Glutathionylation uncouples eNOS, switching it from NO to •O2− generation in a reversible fashion. Two highly conserved cysteinyl residues at the interface between the FMN- and FAD-binding domains are S-glutathionylated and this leads to a novel mechanism of uncoupling resulting from the leak of electrons to molecular oxygen with •O2− generation at the reductase domain. This posttranslational modification can function as a regulatory mechanism for the prevention of the irreversible oxidation of cellular components by limiting the formation of ONOO−. It serves as a molecular switch to flip eNOS from forming the potent anti-inflammatory vasodilator NO to the pro-inflammatory vasoconstrictor •O2− and provides a unique redox mechanism by which eNOS can be regulated.

Thus, S-glutathionylation of eNOS plays an important role in modulation of cellular signaling and vascular function. In view of the importance of NO and eNOS-mediated endothelial dysfunction in disease, identification of this novel redox-signaling pathway provides new insights regarding therapeutic approaches. Indeed, these observations indicate the potential for a new class of therapeutics that reset this S-glutathionylation–dependent redox switch, restoring normal NO synthase function, and such compounds could hold great promise in the prevention, improved treatment, or cure of many of the most prevalent human diseases including heart attack, stroke, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and cancer.

Abbreviations Used

- BH2

dihydrobiopterin

- BH4

tetrahydrobiopterin

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FAD

flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FMN

flavin mononucleotide

- Grx

glutaredoxin

- GSH

glutathione

- heNOS

human eNOS

- L-NAME

N-nitro-l-arginine methylester

- NO

nitric oxide

- ONOO−

peroxynitrite

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Trx

thioredoxin

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01 grants HL63744, HL65608, HL38324 (J.L.Z.), HL081734 (L.J.D.), and HL103846 (C.-A.C.) from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Aota M. Matsuda K. Isowa N. Wada H. Yodoi J. Ban T. Protection against reperfusion-induced arrhythmias by human thioredoxin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1996;27:727–732. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199605000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckman JS. Beckman TW. Chen J. Marshall PA. Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry C. Brosnan MJ. Fennell J. Hamilton CA. Dominiczak AF. Oxidative stress and vascular damage in hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10:247–255. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200103000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas S. Chida AS. Rahman I. Redox modifications of protein-thiols: emerging roles in cell signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boger RH. Sydow K. Borlak J. Thum T. Lenzen H. Schubert B. Tsikas D. Bode-Boger SM. LDL cholesterol upregulates synthesis of asymmetrical dimethylarginine in human endothelial cells: involvement of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Circ Res. 2000;87:99–105. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bredt DS. Hwang PM. Glatt CE. Lowenstein C. Reed RR. Snyder SH. Cloned and expressed nitric oxide synthase structurally resembles cytochrome P-450 reductase. Nature. 1991;351:714–718. doi: 10.1038/351714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardounel AJ. Cui H. Samouilov A. Johnson W. Kearns P. Tsai AL. Berka V. Zweier JL. Evidence for the pathophysiological role of endogenous methylarginines in regulation of endothelial NO production and vascular function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:879–887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CA. Wang TY. Varadharaj S. Reyes LA. Hemann C. Talukder MA. Chen YR. Druhan LJ. Zweier JL. S-glutathionylation uncouples eNOS and regulates its cellular and vascular function. Nature. 2010;468:1115–1118. doi: 10.1038/nature09599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CL. Zhang L. Yeh A. Chen CA. Green-Church KB. Zweier JL. Chen YR. Site-specific S-glutathiolation of mitochondrial NADH ubiquinone reductase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5754–5765. doi: 10.1021/bi602580c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W. Druhan LJ. Chen CA. Hemann C. Chen YR. Berka V. Tsai AL. Zweier JL. Peroxynitrite induces destruction of the tetrahydrobiopterin and heme in endothelial nitric oxide synthase: transition from reversible to irreversible enzyme inhibition. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3129–3137. doi: 10.1021/bi9016632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chrestensen CA. Starke DW. Mieyal JJ. Acute cadmium exposure inactivates thioltransferase (Glutaredoxin), inhibits intracellular reduction of protein-glutathionyl-mixed disulfides, and initiates apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26556–26565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costa NJ. Dahm CC. Hurrell F. Taylor ER. Murphy MP. Interactions of mitochondrial thiols with nitric oxide. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:291–305. doi: 10.1089/152308603322110878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crabtree MJ. Tatham AL. Hale AB. Alp NJ. Channon KM. Critical role for tetrahydrobiopterin recycling by dihydrofolate reductase in regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase coupling: relative importance of the de novo biopterin synthesis versus salvage pathways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:28128–28136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Druhan LJ. Forbes SP. Pope AJ. Chen CA. Zweier JL. Cardounel AJ. Regulation of eNOS-derived superoxide by endogenous methylarginines. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7256–7263. doi: 10.1021/bi702377a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumitrescu C. Biondi R. Xia Y. Cardounel AJ. Druhan LJ. Ambrosio G. Zweier JL. Myocardial ischemia results in tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) oxidation with impaired endothelial function ameliorated by BH4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15081–15086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702986104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes SP. Druhan LJ. Guzman JE. Parinandi N. Zhang L. Green-Church KB. Cardounel AJ. Mechanism of 4-HNE mediated inhibition of hDDAH-1: implications in no regulation. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1819–1826. doi: 10.1021/bi701659n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghezzi P. Regulation of protein function by glutathionylation. Free Radic Res. 2005;39:573–580. doi: 10.1080/10715760500072172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giles GI. Jacob C. Reactive sulfur species: an emerging concept in oxidative stress. Biol Chem. 2002;383:375–388. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giustarini D. Rossi R. Milzani A. Colombo R. Dalle-Donne I. S-glutathionylation: from redox regulation of protein functions to human diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:201–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harbrecht BG. Di Silvio M. Chough V. Kim YM. Simmons RL. Billiar TR. Glutathione regulates nitric oxide synthase in cultured hepatocytes. Ann Surg. 1997;225:76–87. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann H. Schmidt HH. Thiol dependence of nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13443–13452. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang A. Xiao H. Samii JM. Vita JA. Keaney JF., Jr. Contrasting effects of thiol-modulating agents on endothelial NO bioactivity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C719–C725. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.2.C719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunley TE. Iwasaki S. Homma T. Kon V. Nitric oxide and endothelin in pathophysiological settings. Pediatr Nephrol. 1995;9:235–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00860758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin KY. Ito A. Asagami T. Tsao PS. Adimoolam S. Kimoto M. Tsuji H. Reaven GM. Cooke JP. Impaired nitric oxide synthase pathway in diabetes mellitus: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 2002;106:987–992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027109.14149.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.List BM. Klosch B. Volker C. Gorren AC. Sessa WC. Werner ER. Kukovetz WR. Schmidt K. Mayer B. Characterization of bovine endothelial nitric oxide synthase as a homodimer with down-regulated uncoupled NADPH oxidase activity: tetrahydrobiopterin binding kinetics and role of haem in dimerization. Biochem J. 1997;323(Pt 1):159–165. doi: 10.1042/bj3230159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malik G. Nagy N. Ho YS. Maulik N. Das DK. Role of glutaredoxin-1 in cardioprotection: an insight with Glrx1 transgenic and knockout animals. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto T. Akaike T. Sawa T. Miyamoto Y. van der Vliet A. Maeda H. Activation of matrix metalloproteinases by peroxynitrite-induced protein S-glutathiolation via disulfide S-oxide formation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29596–29602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer RM. Ashton DS. Moncada S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature. 1988;333:664–666. doi: 10.1038/333664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panda K. Ghosh S. Stuehr DJ. Calmodulin activates intersubunit electron transfer in the neuronal nitric-oxide synthase dimer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23349–23356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pou S. Pou WS. Bredt DS. Snyder SH. Rosen GM. Generation of superoxide by purified brain nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24173–24176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rapoport RM. Draznin MB. Murad F. Endothelium-dependent relaxation in rat aorta may be mediated through cyclic GMP-dependent protein phosphorylation. Nature. 1983;306:174–176. doi: 10.1038/306174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reddy S. Jones AD. Cross CE. Wong PS. Van Der Vliet A. Inactivation of creatine kinase by S-glutathionylation of the active-site cysteine residue. Biochem J. 2000;347(Pt 3):821–827. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheehy AM. Burson MA. Black SM. Nitric oxide exposure inhibits endothelial NOS activity but not gene expression: a role for superoxide. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L833–L841. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.5.L833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorescu D. Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, and NAD(P)H oxidases in the development and progression of heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2002;8:132–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2002.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuehr DJ. Santolini J. Wang ZQ. Wei CC. Adak S. Update on mechanism and catalytic regulation in the NO synthases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36167–36170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun J. Druhan LJ. Zweier JL. Dose dependent effects of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species on the function of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;471:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun J. Druhan LJ. Zweier JL. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase function shifting the balance of nitric oxide and superoxide production. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;494:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sydow K. Hornig B. Arakawa N. Bode-Boger SM. Tsikas D. Munzel T. Boger RH. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with peripheral arterial disease and chronic hyperhomocysteinemia: potential role of ADMA. Vasc Med. 2004;9:93–101. doi: 10.1191/1358863x04vm538oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sydow K. Schwedhelm E. Arakawa N. Bode-Boger SM. Tsikas D. Hornig B. Frolich JC. Boger RH. ADMA and oxidative stress are responsible for endothelial dysfunction in hyperhomocyst(e)inemia: effects of L-arginine and B vitamins. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:244–252. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00617-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tiefenbacher CP. Chilian WM. Mitchell M. DeFily DV. Restoration of endothelium-dependent vasodilation after reperfusion injury by tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 1996;94:1423–1429. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tummala M. Ryzhov V. Ravi K. Black SM. Identification of the cysteine nitrosylation sites in human endothelial nitric oxide synthase. DNA Cell Biol. 2008;27:25–33. doi: 10.1089/dna.2007.0655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vasquez-Vivar J. Kalyanaraman B. Martasek P. Hogg N. Masters BS. Karoui H. Tordo P. Pritchard KA., Jr. Superoxide generation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase: the influence of cofactors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9220–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vasquez-Vivar J. Martasek P. Whitsett J. Joseph J. Kalyanaraman B. The ratio between tetrahydrobiopterin and oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues controls superoxide release from endothelial nitric oxide synthase: an EPR spin trapping study. Biochem J. 2002;362:733–739. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Venardos KM. Perkins A. Headrick J. Kaye DM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, antioxidant enzyme systems, and selenium: a review. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1539–1549. doi: 10.2174/092986707780831078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang P. Zweier JL. Measurement of nitric oxide and peroxynitrite generation in the postischemic heart. Evidence for peroxynitrite-mediated reperfusion injury. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29223–29230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei CC. Wang ZQ. Tejero J. Yang YP. Hemann C. Hille R. Stuehr DJ. Catalytic reduction of a tetrahydrobiopterin radical within nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11734–11742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709250200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolin MS. Reactive oxygen species and vascular signal transduction mechanisms. Microcirculation. 1996;3:1–17. doi: 10.3109/10739689609146778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia Y. Dawson VL. Dawson TM. Snyder SH. Zweier JL. Nitric oxide synthase generates superoxide and nitric oxide in arginine-depleted cells leading to peroxynitrite-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6770–6774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia Y. Tsai AL. Berka V. Zweier JL. Superoxide generation from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent and tetrahydrobiopterin regulatory process. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25804–25808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia Y. Zweier JL. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6954–6958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J. Li YD. Patel JM. Block ER. Thioredoxin overexpression prevents NO-induced reduction of NO synthase activity in lung endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L288–L293. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.2.L288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zou MH. Shi C. Cohen RA. Oxidation of the zinc-thiolate complex and uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by peroxynitrite. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:817–826. doi: 10.1172/JCI14442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zou MH. Ullrich V. Peroxynitrite formed by simultaneous generation of nitric oxide and superoxide selectively inhibits bovine aortic prostacyclin synthase. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zweier JL. Fertmann J. Wei G. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in postischemic myocardium. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:11–22. doi: 10.1089/152308601750100443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zweier JL. Flaherty JT. Weisfeldt ML. Direct measurement of free radical generation following reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1404–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zweier JL. Talukder MA. The role of oxidants and free radicals in reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]