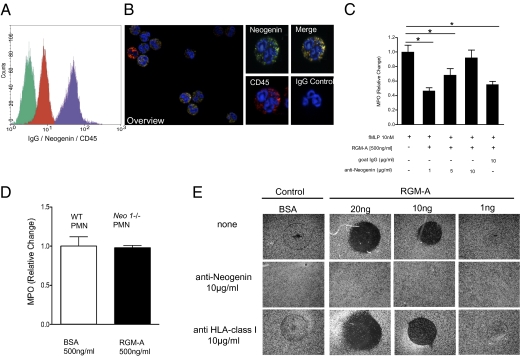

Fig. 4.

RGM attenuates PMN migration through its receptor neogenin in vitro. (A) Flow cytometry (overlay histogram) of freshly isolated human PMNs stained with isotype-matched control antibody (green), anti-CD45 antibody (red), and anti-neogenin antibody (purple). (B) Immunohistochemical staining of freshly isolated human PMNs with anti-neogenin (FITC) or isotype control and anti-CD45 (Cy3) antibodies, with the DAPI label used for nuclear counterstaining. Isotype control antibodies demonstrated no detectable signal levels (Left, overlay; original magnification 200×). Demonstration of CD45+ PMNs to coexpress abundant neogenin (Right; original magnification 600×). (C) PMN transmigration in the presence of distinct concentrations of functionally blocking neogenin antibodies compared with isotype IgG controls. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (D) Neo1−/− PMNs did not respond to RGM-A, revealing an intact, regular migration response (MPO) as demonstrated by WT-derived PMNs after apical BSA application. (E) To investigate a direct contact-repulsion property of RGM-A on PMNs, we analyzed PMN binding to differentially coated surfaces (± RGM-A). The contact-repulsive RGM-A effect on PMN blocked PMN surface binding and was neogenin-dependent. PMN binding was dose-dependently blocked by RGM-A coating (top row). This was completely reversible on preincubation of PMNs with the neogenin antibody (middle row), whereas anti-HLA does not interfere with RGM-A–mediated contact repulsion. One representative experiment out of three experiments conducted is shown.