Abstract

Background: Mortality in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) is high, and patients are likely to require hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and transfusions. The relationships between these events and the MDS complications of anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia are not well understood.

Patients and methods: A total of 1864 patients registered in the United States’ Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program and aged ≥66 years old when diagnosed with MDS in 2001 or 2002 were included. Medicare claims were used to identify MDS complications and utilization (hospitalizations, ED visits, and transfusions) until death or the end of 2005. Mortality was based on SEER data. Kaplan–Meier incidence rates were estimated and multivariable Cox models were used to study the association between complications and outcomes.

Results: The 3-year incidence of anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia was 81%, 25%, and 41%, and the incidence of hospitalization, ED visit, and transfusion was 62%, 42%, and 45%, respectively. Median survival time was 22 months. Cytopenia complications were significantly associated with each of these outcomes.

Conclusions: All types of cytopenia are common among patients with MDS and are risk factors for high rates of health care utilization and mortality. Management of the complications of MDS may improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: anemia; health services research, mortality; myelodysplastic syndromes; neutropenia; thrombocytopenia

introduction

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous group of myeloid clonal hematopoietic disorders in which immature blood cells die either in the bone marrow or soon after they enter into circulation. The majority of MDS cases are not associated with known exposures (de novo cases) although genotoxic exposures, such as chemotherapy, may also be associated with its development [1]. Depending on the subtype of de novo MDS, median survival estimates currently range from 5 months to 6 years if left untreated [2]. MDS primarily affects the older population, and incidence has been shown to increase with age [3–5]. In addition, there is some evidence that MDS incidence rates may be increasing in the population [6]. The incidence of MDS could continue to rise due to the aging of the population, improvements in geriatric medicine, physician awareness, and other factors [6, 7].

Clinical complications of MDS can include one or more types of peripheral cytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia), which can in turn cause increased susceptibility to serious infections, bleeding, and other adverse events [8]. Also, patients with MDS are at increased risk for developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a cancer with a 95% 5-year mortality rate in patients ≥65 years [6]. However, more patients with MDS die of consequences of MDS than from AML [9]. The cytopenias can each lead to hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and transfusions over the course of the disease. However, the rates of health care utilization in patients with MDS are unknown, and the association between the key complications of MDS on rates of health care utilization and mortality is also unknown.

Characterizing the relationship between the key complications of MDS and health care utilization and mortality could lead to better understanding of the burden of MDS on the patient and health care system. The first objective of this study was to estimate the prevalence and incidence of anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia in a population-based sample of older patients with MDS. The second was to estimate the incidence rates of hospitalization, ED visits, transfusions, and mortality in these patients. The final objective was to assess the independent association of each cytopenia on outcomes.

patients and methods

data source

We used the National Cancer Institute (NCI) SEER–Medicare linked database to identify patients diagnosed with MDS [10]. The SEER database is a population-based registry that tracks information about cancer patients from certain geographically defined areas in the United States. The database includes patient demographics, the dates and other characteristics of primary and subsequent cancer diagnoses, and follow-up on vital status. During the period from which our patients were identified, 17 geographical areas representing ∼26% of the USA population were covered by the SEER registry [11].

The Medicare data linked to the SEER database include Parts A and B claims for hospital, physician, and outpatient claims (including hospital outpatient clinics). The NCI reports that ∼93% of patients aged ≥65 years in the SEER files are matched to the Medicare enrollment files [12].

patient eligibility

We selected our study population from individuals residing in areas captured by the SEER registry who were diagnosed with MDS from January 2001 to December 2002 and who did not have any previously recorded cancer diagnoses. We identified MDS using International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, histology codes in the SEER registry which closely correspond to the classification system proposed by the World Health Organization [13–15]. These included the following seven codes: 9980 [refractory anemia (RA)]; 9982 (RA with sideroblasts); 9983 [refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB)]; 9985 (refractory cytopenia with multi-lineage dysplasia); 9986 (5q deletion syndrome); 9987 (therapy-related MDS); and 9989 [MDS, not otherwise specified (NOS)].

The Medicare data linked to our patient population included claims from 1 January 1997 until 31 December 2005. Of all 3025 patients diagnosed with MDS in 2001 or 2002, 326 were excluded for being under age 66, 130 additional patients were excluded for not having both Parts A and B Medicare claims continuously for at least one full year before MDS diagnosis, and 554 were excluded for having Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) coverage in the year before MDS diagnosis. These exclusions were made in order to accurately identify prevalent symptoms and comorbid conditions at the time of diagnosis. In addition, we excluded 151 patients who died in the month of their diagnosis or who were missing the month of diagnosis.

patient characteristics

The date of MDS diagnosis, age at diagnosis, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic characteristics, and date of death were all taken from the SEER database. Age at diagnosis was categorized as 66–69, 70–74, 75–79, and ≥80 years old. Race and ethnicity were defined using the SEER recoded race variable which categorizes patients as white, black, Hispanic, and other (which consists predominately of American Indian/Native Alaskan, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and Asian). Socioeconomic characteristics included information about college education, poverty, and population density in the census tract where patients were residing at the time of diagnosis [10].

A comorbidity score, based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index [16] with adaptations for cancer patients suggested by Deyo and Romano [17, 18], was calculated using Medicare claims data from the 12 months before the MDS diagnosis date according to an algorithm supplied by the NCI [19]. Comorbidity scores were categorized into 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 conditions.

MDS complications and outcomes

We identified prevalent anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia at the time of MDS diagnosis using Medicare claims from the 6 months before and during the month of MDS diagnosis (the prevalence period). Incident cytopenia cases were identified from the month after MDS diagnosis to the end of observation (the incidence period). Qualifying Medicare claims included International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, revenue center codes, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes (see Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Claims likely to be made only for testing purposes were excluded from prevalent and incident cytopenia case counts. At least one inpatient or outpatient code was required to identify cytopenia. If there was an outpatient code but no inpatient code in the prevalence or incidence period, a second outpatient code was required at least 30 days after the first one occurred for confirmation. All inpatient and outpatient diagnosis codes for cytopenia were included in this algorithm. Procedure codes were included in cytopenia definitions if they indicated transfusion therapy [red blood cell (RBC) for anemia and platelet for thrombocytopenia] or chemotherapy (darbepoetin or epoetin alfa for anemia, filgrastim or pegfilgrastim for neutropenia, and oprelvekin for thrombocytopenia).

Hospitalizations, ED visits, and transfusions were also identified using Medicare claims. Both short- and long-term hospital stays were counted as hospitalizations, excluding ED visits, outpatient hospital visits, and skilled nursing facility stays. MDS-specific hospitalizations were defined as those associated with bleeding or fever. They were based on Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) and primary diagnosis codes, or secondary diagnosis codes if the primary code was for MDS. ED visits were determined from physician claims for care given in any ED. ICD-9-CM procedure codes, HCPCS, and revenue center codes were used to identify the first of any type of transfusion, as well as the first RBC transfusion, platelet transfusion, or other type of transfusion. Death dates and causes of death were determined using the SEER data.

Claims were searched from the end of the month of MDS diagnosis until the first occurrence of the complication or the end of observation. The end of the observation period was the patients’ date of death, the end of Medicare Part A or B coverage, the beginning of HMO coverage, a new non-AML cancer diagnosis, or 31 December 2005 (whichever came first).

statistical analyses

We calculated the 3-month and 3-year cumulative incidence rates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method and plotted the KM cumulative incidence of each complication and outcome over the study period. Patients diagnosed with a cytopenia during the prevalence period were excluded from cytopenia incidence rate calculations.

Cox regression models were used to calculate multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for all utilization outcomes (hospitalizations, ED visits, and transfusions). All models included the patients' age category, gender, race/ethnicity, NCI comorbidity score, year of MDS diagnosis, and their census tract's education, poverty, and population density. In addition, all models included time-varying covariates of prevalent or incident anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. Prevalent cytopenia cases were incorporated into time-varying cytopenia covariates by indicating their presence during the entire timeline. Transfusions were included in the definition of cytopenia for all models except those with transfusion outcomes. The frequency and percent of hospitalizations for events other than bleeding and fever were reported.

Multivariable Cox models adjusted for baseline characteristics were also used to determine whether cytopenia, hospitalizations, and ED visits were associated with risk of death. In addition, the frequency and percent of the most common SEER-coded causes of death and of AML, other leukemia, and other malignancies were reported. SEER had no specific code for MDS as the cause of death.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to study the impact of using SEER histology codes for RA, RA with sideroblasts, and RAEB in addition to claims data to identify prevalent anemia. In addition, we tested the impact of adjusting our models for MDS subtypes (all histology codes). Finally, analyses were repeated after extending the prevalence period for identifying cytopenia claims to a full year before diagnosis. Analyses were conducted using Stata 10.1 for Windows (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). All P values reported are two sided.

results

patient characteristics

The final population included 1864 patients whose mean age at the time of diagnosis was 78.8 years; 47% were female and 85% were white. The mean number of comorbid conditions at the time of diagnosis was 1.2, with a range of 0–10. Forty-four percent were diagnosed with the RA, RA with sideroblast, or RAEB subtype. Eighty-five percent had been diagnosed with prevalent anemia, 13% with neutropenia, and 23% with thrombocytopenia by the time of MDS diagnosis. See Table 1 for additional baseline characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients diagnosed with MDS in the United States, 2001–2002

| Baseline characteristics | Level | n (%) |

| Age | 66–69 | 184 (10) |

| 70–74 | 372 (20) | |

| 75–79 | 444 (24) | |

| ≥80 | 864 (46) | |

| Gender | Male | 986 (53) |

| Female | 878 (47) | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 1591 (85) |

| Black | 120 (6) | |

| Hispanic | 81 (4) | |

| Other | 72 (4) | |

| NCI comorbidity score | 0 | 808 (45) |

| 1 | 468 (26) | |

| 2 | 259 (14) | |

| ≥3 | 275 (15) | |

| Percentage of 25+ year-olds in census tract with some college | 0–24 | 1027 (56) |

| ≥25 | 814 (44) | |

| Percent living in poverty in census tract | <5 | 555 (30) |

| 5–9 | 538 (29) | |

| ≥10 | 748 (41) | |

| Population density | Big metropolitan | 1103 (59) |

| Metropolitan | 470 (25) | |

| Urban | 89 (5) | |

| Less urban/rural | 202 (11) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 2001 | 926 (50) |

| 2002 | 938 (50) | |

| MDS subtypea | Refractory anemia | 353 (19) |

| Refractory anemia with sideroblasts | 229 (12) | |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts | 240 (13) | |

| Refractory cytopenia with multi-lineage dysplasia | 57 (3) | |

| 5q deletion syndrome | 40 (2) | |

| Therapy related | 24 (1) | |

| MDS not otherwise specified | 921 (49) | |

| Prevalent anemia | 1589 (85) | |

| Prevalent neutropenia | 239 (13) | |

| Prevalent thrombocytopenia | 425 (23) | |

| Transfusions received | Any type | 488 (26) |

| Red blood cell | 470 (25) | |

| Platelet | 46 (2) | |

| Other/unknown | 243 (13) |

Based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition, histology codes recommended by the World Health Organization.

MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

MDS complications and health care utilization

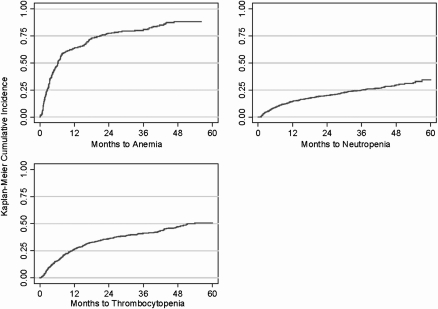

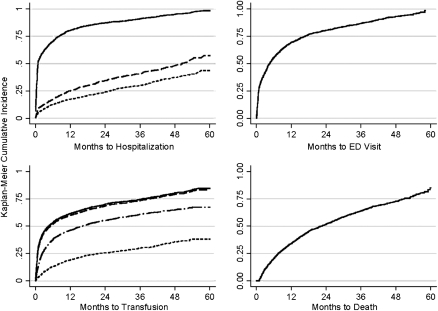

The incidence rates of anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia for patients not diagnosed with these complications by the time of MDS diagnosis are presented in Table 2. KM incidence plots for these complications over the study period are shown in Figure 1. Incidence rates for hospitalizations, ED visits, and transfusions are presented in Table 3, and cumulative incidence plots over the study period are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Incidence of key complications in patients diagnosed with MDS in the United States, 2001–2002

| Complicationa | Months to first occurrence |

3-Month cumulative incidenceb |

3-Year cumulative incidenceb |

|||

| Median | IQR | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Anemia | 5 | 2–6 | 28 | 23–33 | 81 | 76–86 |

| Neutropenia | 16 | 5–39 | 5 | 4–6 | 25 | 22–28 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 15 | 5–39 | 9 | 8–11 | 41 | 38–44 |

Among patients without the complication by the time of MDS diagnosis.

Estimated by Kaplan–Meier method.

MDS, myelodysplastic syndromes; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia after diagnosis in patients diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndromes in the United States, 2001–2002.

Table 3.

Incidence of health care utilization and mortality outcomes in patients diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndromes in the United States, 2001–2002

| Outcome event | Months to first occurrence |

3-Month cumulative incidencea |

3-Year cumulative incidencea |

|||

| Median | IQR | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Hospitalization | ||||||

| Any reason | 1 | 0.3–8 | 62 | 60–64 | 91 | 90–92 |

| Bleeding | 14 | 4–37 | 12 | 11–14 | 41 | 38–44 |

| Fever | 16 | 5–38 | 9 | 7–10 | 30 | 27–33 |

| ED visit | 4 | 1–13 | 42 | 39–44 | 87 | 85–88 |

| Transfusion | ||||||

| Any type | 3 | 1–20 | 45 | 43–47 | 75 | 72–77 |

| Red blood cell | 4 | 1–21 | 44 | 41–46 | 74 | 71–76 |

| Platelet | 16 | 5–39 | 7 | 6–9 | 29 | 27–32 |

| Other/unknown | 6 | 2–28 | 23 | 21–25 | 57 | 54–60 |

| Death | 22 | 8–42 | 11 | 10–12 | 64 | 62–66 |

Estimated by Kaplan–Meier method.

CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 2.

Incidence of hospitalization (from top to bottom: any reason, bleeding event, fever), emergency department (ED) visits, transfusions (from top to bottom: any type, red blood cell, other/unknown, platelet), and death after diagnosis in patients diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndromes in the United States, 2001–2002.

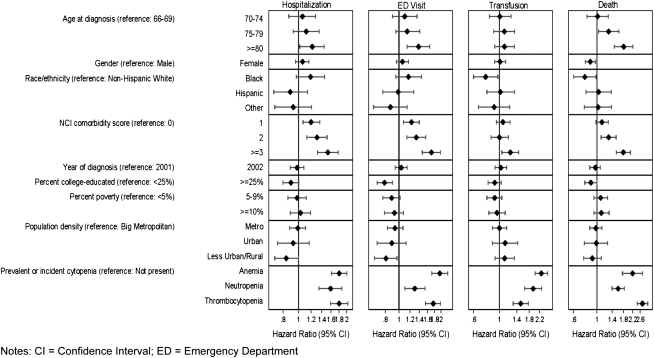

In multivariable Cox models, all types of cytopenia were independently associated with higher utilization. There was a significantly higher risk of hospitalization for patients with cytopenia (anemia HR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.61–2.01; neutropenia HR = 1.59, 95% CI 1.34–1.87; thrombocytopenia HR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.59–2.04), ED visits (anemia HR = 1.96, 95% CI 1.72–2.24; neutropenia HR = 1.30, 95% CI 1.10–1.54; thrombocytopenia HR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.55–1.99), and transfusions (anemia HR = 2.28, 95% CI 2.01–2.59; neutropenia HR = 1.94, 95% CI 1.64–2.30; thrombocytopenia HR = 1.52, 95% CI 1.31–1.83). Other independently associated predictors (P < 0.05) of hospitalization and ED visits included age >80 years versus 66–69 years old, rural versus big metropolitan census tract areas, and one or more versus no comorbidities. Other independently associated predictors of transfusions included black versus white race and more than three versus no comorbidities (Figure 3). Thrombocytopenia was the strongest independent predictor of being hospitalized for a bleeding event (HR = 3.34, 95% CI 2.81–3.97). Neutropenia was the strongest predictor of being hospitalized for a fever (HR = 3.69, 95% CI 2.97–4.58).

Figure 3.

Multivariable analysis of the characteristics and complications associated with health care utilization and mortality in patients diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndromes in the United States, 2001–2002.

Among the patients hospitalized during our study, 8% were first hospitalized for a bleeding event and 5% were first hospitalized for a fever. Of the remaining hospitalized patients, the most common reasons according to DRG codes were lymphoma and non-acute leukemia with complications (DRG code 403, 17%), RBC disorders (DRG code 395, 12%), simple pneumonia and pleurisy with complications (DRG code 89, 5%), and heart failure and shock (DRG code 127, 5%).

MDS complications and mortality

Incidence rates for death are presented in Table 3, and cumulative incidence over the entire study period is shown in Figure 2. Adjusting for baseline characteristics, those diagnosed with prevalent or incident cytopenia were significantly more likely to die during the study period (anemia HR = 2.20, 95% CI 1.76–2.75; neutropenia HR = 1.60, 95% CI 1.40–1.83; and thrombocytopenia HR = 2.73, 95% CI 2.43–3.07). Other independently associated predictors (P < 0.05) of mortality included female gender and black versus white race (Figure 3).

In a multivariable model including baseline characteristics and time-varying covariates for cytopenia and utilization, hospitalization for any reason was the strongest predictor of death (HR = 6.54, 95% CI 4.70–9.11), followed by incident thrombocytopenia (HR = 2.27, 95% CI 2.02–2.56) and ED visits (HR = 2.09, 95% CI 1.77–2.47).

The most common specific causes of death according to SEER were malignant cancer (35%), in situ, benign, or unknown behavior neoplasm (25%), and diseases of the heart (15%). Ten percent died of AML, 9% died of another form of leukemia, and 16% died of other malignancies. Nonspecific or unknown causes of death accounted for 19% of all deaths.

sensitivity analyses

The prevalence of anemia at diagnosis would have been 91% if the SEER histology codes for RA, RA with sideroblasts, and RAEB had been included in the definition. However, the direction and significance of the associations between incident cytopenia and the outcomes remained similar after adding these histology codes to the definition of prevalent anemia (results not shown). Adjusting the models for MDS subtype and extending the period for identifying all prevalent cytopenias to a full year before diagnosis also resulted in similar findings.

conclusions

This study confirms findings from previous studies in addition to adding important new information about the natural history of MDS with regard to health care utilization and mortality. Our cohort had a distribution of MDS subtypes and 3-year mortality rates similar to those found in other recent studies of elderly patients with MDS [20, 21]. We also found that elderly patients are frequently diagnosed with anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia in inpatient and outpatient settings before they are diagnosed with MDS. We describe for the first time cytopenia incidence rates in patients with MDS for whom cytopenia was not previously diagnosed. In addition, we describe in detail how prevalent and incident cytopenia complications are associated with high health care utilization rates and mortality.

A large proportion of the elderly patients with MDS in this study were either hospitalized (62%) or went to an ED (42%) within 3 months of diagnosis. Bleeding and fevers were often listed as the primary reasons for these hospitalizations. We chose to study these reasons for hospitalization because they are specific symptoms that may be attributed to thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, respectively, and are known to be risk factors for death among patients with MDS [22, 23]. There are, of course, other possible MDS-related reasons for hospitalization, ED visits, and death. Pneumonia and pleurisy or cardiac failure are also likely to be attributable to the MDS, for example. Without a healthy comparison cohort of similar age and without more specific information (such as autopsy data), it is impossible to identify the mechanism or excess risk that MDS conferred on these cause-specific events.

Though the goal of the present study was to estimate event rates and associations within the MDS population, comparisons with a non-cancer control population would be valuable. While this was beyond the current scope of this research, a recent study compared patients with MDS with other Medicare beneficiaries and found that MDS and transfusion dependency are associated with increased risk of comorbidity and mortality [24]. Our finding that thrombocytopenia and neutropenia were the strongest respective independent predictors of hospitalization for bleeding and fever also provides some support for MDS being the underlying cause of these particular events.

A transfusion of any kind occurred in the majority (three-quarters) of our patients within 3 years. Transfusions are still a common form of supportive therapy and will most likely continue to be used for patient management [25–27]. Although pharmacotherapy combined with transfusion therapy has been the preferred method for treating MDS for some time, transfusion dependency is still a common occurrence and is a strong predictor of survival and progression to AML [28, 29].

Our results show an association between all types of prevalent and incident cytopenia and mortality, independent of patient demographics, the number of comorbidities at the time of MDS diagnosis, and other factors. One explanation for this is that the complications of these cytopenias, particularly bleeding and infections, may increase the risk of death. Other studies have also reported that severe bleeding events and infections account for a large portion MDS-related deaths [22]. In this study, we were not able to estimate how many died of bleeding or infection, but we know that only 10% died of AML, 25% died of other types of leukemia or cancers, and 25% died of an ‘in situ, benign, or unknown behavior neoplasm’. Because there is no specific code for MDS as the cause of death, we cannot determine this quantitatively.

It is possible that many of the remaining deaths were due to unrelated events or comorbidity. Comorbidity has been shown to be a significant and independent predictor of mortality in elderly patients with MDS [30]. Regardless of cause, over half of our cohort of patients with MDS (with an average age of almost 80 years old) died in <2 years. In contrast, the average life expectancy for 80-year-olds in the USA population in 2002 was ∼9 years [31]. More specific analyses are needed to more precisely estimate the excess risk associated with MDS, but it is clearly substantial.

One limitation of this study is that we relied on administrative claims data to identify prevalent and incident cytopenias, which may have resulted in an underestimate of these complications. Although other methods would have been possible and valid (such as using histology codes to identify anemia patients), our conclusions were not sensitive to any of the alternate definitions we tested. In addition, our cohort consisted of patients aged ≥66 years who were enrolled in non-HMO Medicare Parts A and B for at least 1 year before MDS diagnosis and throughout follow-up. Thus, our findings may not accurately reflect what happens with younger and privately insured MDS patients.

Other limitations are related primarily to the fact that we used patients diagnosed and reported to SEER in 2001 and 2002. MDS became reportable to SEER in 2001, and MDS incidence rates increased in the USA population in the years following, suggesting a possible change in capture rates due to reporting issues [20]. Although we cannot determine how much influence this has had on our cohort, we had good representation of patients from different sociodemographic subgroups, and we adjusted for these characteristics in all of our models. Reporting issues may be related to SEER region and differing methods for case finding [32], but these are likely to be adequately accounted for through sociodemographic adjustments. Also related to the capture period is the fact that we did not have access to data on the percentage of myeloblasts or other morphological and genetic characteristics of our patients. Thus, we were limited in our ability to identify distinct subtypes of MDS. Nearly half of the patients in our study population were diagnosed with a nonspecific subtype of MDS according to the SEER histology codes available in the data. This group likely represents multiple subtypes that were not yet differentiable in 2001 or 2002, at least by data available to SEER. Despite many efforts to standardize the criteria for classifying subtypes using detailed laboratory findings, this still poses a major challenge to clinicians and researchers [33, 34].

Despite these limitations, findings from this and other recent epidemiological studies can serve as important comparison data for future studies. It should also be noted that the fact that our cohort was diagnosed in 2001 and 2002 and followed through 2005 means that our study period predates the approval or wide use of many newer chemotherapies. This ensures that we were able to capture the natural history of disease and avoid confounding from therapies that might cause or exacerbate certain cytopenias, especially thrombocytopenia [22].

Quantifying the effect of incident complications on outcomes among patients with MDS emphasizes the importance of preventing these complications where possible and managing them effectively when they occur. They have significant effects on both individual patients’ outcomes and the health care system.

funding

This work was supported by Amgen, Inc., through a contract with Outcomes Insights, Inc. This contract specifies that the authors are free to publish findings based on this research without restriction.

disclosure

Outcomes Insights, Inc., has ongoing research projects with Amgen, Inc., who markets romiplostim for use in patients with immune thrombocytopenia purpura. However, at the time of writing, romiplostim was not indicated for use in patients with MDS. KL, MD, and RG are employees of Outcomes Insights, Inc. JJ and KK did not receive any compensation for their participation in this research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services, Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER–Medicare database.

References

- 1.Langston AA, Walling R, Winton EF. Update on myelodysplastic syndromes: new approaches to classification and therapy. Semin Oncol. 2004;31(2) Suppl 4:72–79. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™ Myelodsyplastic Syndromes. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc.; 2007. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp (02 February 2008, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aul C, Gattermann N, Schneider W. Age-related incidence and other epidemiological aspects of myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 1992;82(2):358–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb06430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazzola M, Malcovati L. Myelodysplastic syndromes—coping with ineffective hematopoiesis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):536–538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynadié M, Verret C, Moskovtchenko P, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of myelodysplastic syndrome in a well-defined French population. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(2):288–290. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2009. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006 (23 May 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dansey R. Myelodysplasia. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12(1):13–21. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blinder VS, Roboz GJ. Hematopoietic growth factors in myelodysplastic syndromes. Curr Hematol Rep. 2003;2(6):453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.List AF, Vardiman J, Issa JP, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2004;1:297–317. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2004.1.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8) Suppl:IV-3–IV-18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. SEER Data, 1973–2006. Bethesda, MD: Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute; 2007. http://seer.cancer.gov/data (23 February 2007, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute. SEER-Medicare: How the SEER & Medicare Data Are Linked. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/overview/linked.html (23 February 2007, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett JM. World Health Organization classification of the acute leukemias and myelodysplastic syndrome. Int J Hematol. 2000;72(2):131–133. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2003;101(7):2895–2896. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romano PS, Roos LL, Luft HS, et al. A comparison of administrative versus clinical data: coronary artery bypass surgery as an example. Ischemic Heart Disease Patient Outcomes Research Team. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(3):249–260. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young JL, Jr, Roffers SD, Ries LAG, et al. SEER Summary Staging Manual—2000: Codes and Coding Instructions. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2001.. Pub. No. 01-4969. 2001; http://seer.cancer.gov/tools/ssm/ (23 February 2007, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma X, Does M, Raza A, et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes: incidence and survival in the United States. Cancer. 2007;109(8):1536–1542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rollison DE, Howlader N, Smith MT, et al. Epidemiology of myelodysplastic syndromes and chronic myeloproliferative disorders in the United States, 2001–2004, using data from the NAACCR and SEER programs. Blood. 2008;112(1):45–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantarjian H, Giles F, List A, et al. The incidence and impact of thrombocytopenia in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1705–1714. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dayyani F, Conley AP, Strom SS, et al. Cause of death in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2010;116(9):2174–2179. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg SL, Chen E, Corral M, et al. Incidence and clinical complications of myelodysplastic syndromes among United States Medicare beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2847–2852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mufti GJ, Chen TL. Changing the treatment paradigm in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Control. 2008;15(Suppl):14–28. doi: 10.1177/107327480801504s03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.List AF. Treatment strategies to optimize clinical benefit in the patient with myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Control. 2008;15(Suppl):29–39. doi: 10.1177/107327480801504s04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekeres MA, Schoonen M, Kantarjian H, et al. Characteristics of US patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: results of six cross-sectional physician surveys. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(21):1542–15. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gore SD, Hermes-DeSantis ER. Future directions in myelodysplastic syndrome: newer agents and the role of combination approaches. Cancer Control. 2008;15(Suppl):40–49. doi: 10.1177/107327480801504s05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malcovati L, Germing U, Kuendgen A, et al. Time-dependent prognostic scoring system for predicting survival and leukemic evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(23):3503–351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang R, Gross CP, Halene S, et al. Comorbidities and survival in a large cohort of patients with newly diagnosed myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Res. 2009;33(12):1594–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kochanek KD, Smith BL. National Vital Statistics Report. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2002. Vol. 52, no. 13. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Roos AJ, Deeg HJ, Davis S. A population-based study of survival in patients with secondary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): impact of type and treatment of primary cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(10):1199–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kantarjian H, et al. World Health Organization (WHO) international working group. Report of an international working group to standardize response criteria for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2000;96(12):3671–3674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steensma DP, Tefferi A. The myelodysplastic syndrome(s): a perspective and review highlighting current controversies. Leuk Res. 2003;27(2):95–120. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.