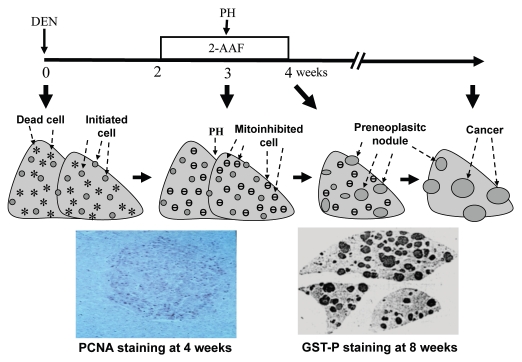

Figure 2.

Use of Farber's “resistant hepatocyte” model of liver carcinogenesis96 as an example to illustrate how mitoinhibition and compensatory proliferation promote carcinogenesis: Rats were injected with a necrotic dose of diethylnitrosamine (DEN) to cause hepatocyte death (stars) and cause some critical genetic damage in some hepatocytes. The liver would regenerate in two weeks, during which the altered genes are passed to nascent hepatocytes and initiated cells are thus created (spots). The rats were then treated with 2-acetylaminofluorene (2-AAF) for two weeks at a low dose that inhibits proliferation of normal hepatocytes, but initiated cells are resistant to this mitoinhibition. When a partial hepatectomy (PH) is performed to remove 2/3 of the liver in the middle of the 2-AAF treatment to stimulate liver regeneration again, initiated cells in the remaining liver will proliferate robustly and form preneoplastic nodules, because normal cells are mitoinhibited (.). As one piece of evidence (the left photo at the bottom part), a liver collected one week after PH was immunohistochemically stained for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) to visualize proliferating cells, which are mainly in a colony (i.e., a nodule) of initiated cells, but rarely in the surrounding area that also receives the same regeneration signal from PH.203 Another rat was sacrificed four weeks after cessation of 2-AAF treatment and the remaining three lobes of the liver were sectioned and immunohistochemically stained for the P form of glutathione S transferase (GST-P), which is a marker for the initiated, pre-neoplastic nodules (right, bottom photo). Many nodules will later regress gradually but some will progress to cancers a few months later.