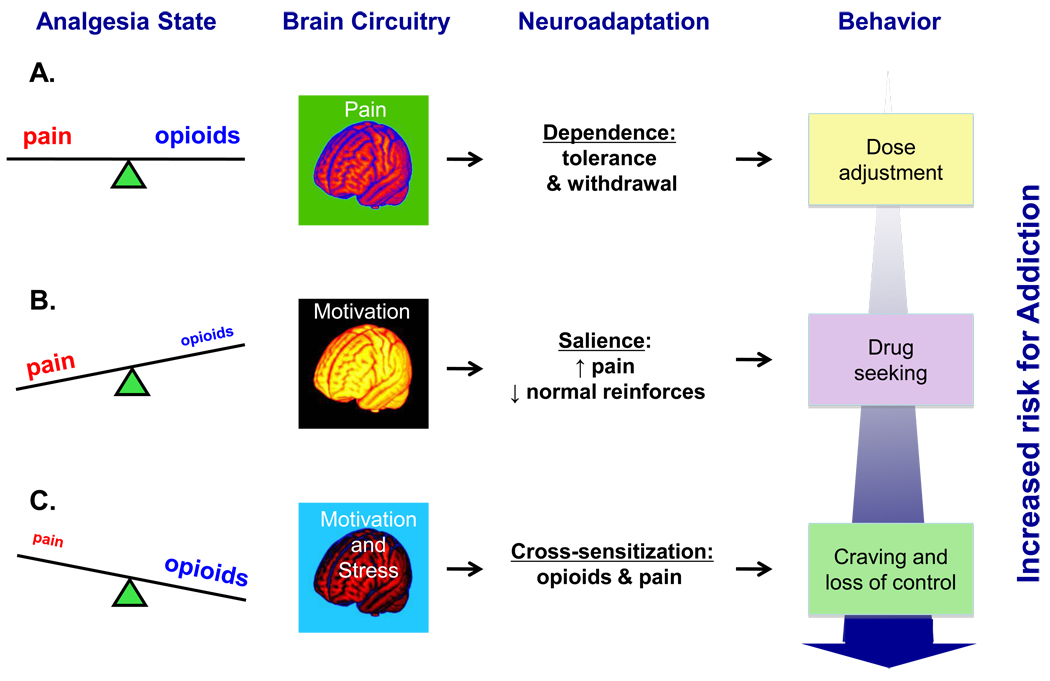

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of potential mechanisms involved in drug-related motivational changes during adequate-, under- or over-treatment of pain with opioid analgesics.

(A) Pain relief owing to adequate analgesia restores homeostatic equilibrium and seldom produces addiction 67, 92 which nonetheless may arise 15, 88 in the context of intricate relationships among various genetic, clinical, pharmacokinetic and psychosocial factors. Dependence on opioid analgesics, including tolerance (i.e., diminution of drug’s effectiveness) and resultant withdrawal 88, 94 is a more likely outcome and it calls for a gradual and judicial dose escalation 181. (B) Inadequately treated or untreated pain activates dopaminergic ventral striatal neurotransmission involved in motivational processing (15) leading to heightened incentive salience attribution to pain and to pain-related stimuli. Opioid analgesics is one of such stimuli that becomes a sensitized motivational target capturing greater attentional resources and leading to expenditure of greater behavioral effort relative to normal reinforcers 93, 104, 105, 182. Even though this state is viewed as pseudo- rather than genuine addiction 84, the latter’s features may predominate with time, given the potential opioid overuse in the form of ill-fated attempts to ‘self-medicate’ perceivably intolerable pain and pain-related anxiety 67. (C) Similar to pain effects discussed in the preceding caption, changes in the mesolimbic dopaminergic circuitry induced by opioids, taken at the doses exceeding the homeostatic need for pain alleviation, are responsible for transforming regular motivational drives into heightened incentive salience assigned to opioids or to opioid-related cues, that is to say drug craving 34. Additional critical aspect of opioid overuse in the context of an ongoing pain condition is the amplification of the physical and emotional aspects of pain. The latter emotional component, recently termed “hyperkatifeia” 67, is purportedly mediated via norepinephrine and consequent corticotropin-releasing factor hypersecretion within the extended amygdala structures underlying anxiety and fear 183, 184 namely the central nucleus of the amygdala 185, 186 and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis 187–189. Notably, such a cross-sensitization phenomenon is typical of addictive substances and entails a situation when prior exposure to one stimulus (e.g., drug) increases subsequent response to itself 111–113, 190 and to a different stimulus (e.g., stress; 114, 116, 189). Hence, a common outcome in pain patients could be generation of the ‘spiraling distress cycle’ 79, 191 whereby opioid overuse provoked by enhanced pain salience (see Caption B) produces additional deterioration in the pain 117–120 and emotional 67 problems, leading to further opioid consumption that may eventually produce a transition from excessive opioid use to bona fide addiction