To the Editor: Anaplasmosis is a disease caused by bacteria of the genus Anaplasma. A. marginale, A. centrale, A. phagocytophilum, A. ovis, A. bovis, and A. platys are obligate intracellular bacteria that infect vertebrate and invertebrate host cells. A. ovis, which is transmitted primarily by Rhipicephalus bursa ticks, is an intraerythrocytic rickettsial pathogen of sheep, goats, and wild ruminants (1).

Anaplasma spp. infections in humans have been reported in Cyprus (2,3). We report infection of a human with a strain of Anaplasma sp. other than A. phagocytophilum, which was detected by PCR amplification of anaplasmatic 16S rRNA, major surface protein 4 (msp4), and heat shock protein 60 (groEL) genes.

A 27-year-old woman was admitted to the pathology clinic of a hospital in Famagusta, Cyprus on May 14, 2007, with an 11-day history of fever (<39.5°C) after a tick bite. Before admission, the patient was treated with cefixime (400 mg/d for 3 days) and cefradine (2 g/d for 2 days) without abatement of the fever. Physical examination showed hepatosplenomegaly and an enlarged lymph node.

Initial laboratory examinations showed moderate anemia (hemoglobin 11.5 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (95,000 thrombocytes/mm3), increased levels of transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase 178 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 313 U/L, γ-glutamyl transferase 79 U/L, lactate dehydrogenase 698 U/L), an increased level of C-reactive protein (10.4 mg/L), and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (80 mm/h). Blood samples were obtained from the patient at the time of admission and 7 days and 3 months later. Results of blood and urine cultures were negative for bacteria. A chest radiograph, computed tomography of the abdomen, and an echocardiograph of the heart showed unremarkable results. Blood samples were negative for antibodies against cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis, HIV, mycoplasma, coxackie virus, adenovirus, parvovirus, Coxiella burnetii, R. conorii, and R. typhi, and for rheumatoid factors. A lymph node biopsy specimen was negative for infiltration and malignancy. After treatment with doxycycline (200 mg/day for 11 days), ceftriaxone (2 g/day for 5 days), and imipenem/cilastatin (1,500 mg/day for 1 day), the patient recovered and was discharged 17 days after hospitalization.

Three serum samples from the patient were tested in Crete, Greece, for immunoglobulin (Ig) G and IgM against A. phagocytophilum antigen by using an immunofluorescent antibody assay (Focus Diagnostics, Cypress, CA, USA). Serologic analysis showed IgG titers of 0, 0, and 128 and IgM titers of 20, 20, and 20 against A. phagocytophilum in the 3 serum samples, respectively.

Because the blood samples were transported frozen, detection of morulae was not possible. DNA was extracted by using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). PCR amplifications (MyCycler DNA thermal cycler; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were conducted for the anaplasmatic 16S rRNA gene; A. marginale, A. centrale, and A. ovis heat shock protein 60 (groEL) genes; and A. marginale, A. centrale, and A. ovis major surface protein 4 (msp4) genes (4,5). DNA from previous studies in Cyprus (4,5) was used as a positive control. Double-distilled water was used as a negative control.

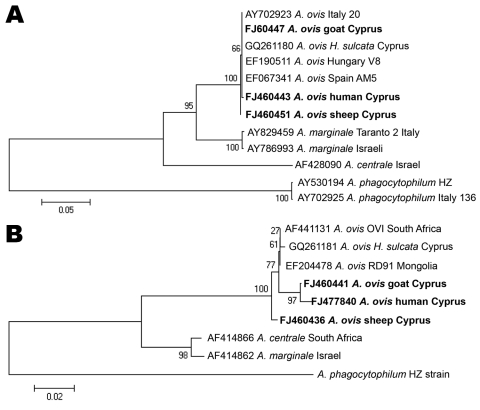

PCR amplicons were purified by using the QIAquick Spin PCR Product Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced on a 4200 double-beam automated sequencer (LI-Cor, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). Sequences were processed by using ClustalW2 software (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html) and the GenBank/European Molecular Biology database library (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using MEGA 4 software (www.megasoftware.net).

The first blood sample was positive for A. ovis by PCR; the other 2 were negative. A 16S rRNA gene sequence (EU448141) from the positive sample showed 100% similarity with other Anaplasma spp. sequences (A. marginale, A. centrale, A. ovis) in GenBank. Anaplasma sp. groEL and msp4 genes showed a 1,650-bp sequence (FJ477840, corresponding to 748 of 1,650 bp) and an 852-bp sequence (FJ460443) for these genes, respectively. Phylogenetic trees (Figure) were constructed by using A. ovis strains detected in sheep and goats in Cyprus (5).

Figure.

Evolutionary trees based on major surface protein 4 (A) and heat shock protein 60 (B) genes sequences of Anaplasma phagocytophilum, A. marginale, and A. ovis. Evolutionary history was inferred by using the neighbor-joining method. H. sulcata; Haemaphysalis sulcata. A) Optimal tree (branch length = 0.87919908) is shown. Percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) are shown. B) Optimal tree (branch length = 0.34047351) is shown. Percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown. Trees are drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. Evolutionary distances were computed by using the Kimura 2-parameter method. Strains detected in Cyprus are indicated in boldface. Scale bars indicate number of base substitutions per site.

Fever is common in cases of human infection with A. phagocytophilum (6). We also detected thrombocytopenia and elevated levels of transaminases. However, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and anemia are not common in persons infected with A. phagocytophilum.

Immunofluorescent antibody analysis showed weak antibody titers against A. phagocytophilum. Serologic cross-reactivity of Anaplasma spp. is caused by conservation of major surface protein sequences (7).

A. phagocytophilum infection usually resolves after treatment with doxycyline for 4 days (8). The patient reported here was treated with doxycycline for 11 days. However, 1 case is not sufficient to form conclusions on severity and duration of illness.

In a study conducted in Cyprus, Anaplasma sp. was identified in birds (9). Because birds may be carriers of zoonotic pathogens, infection of humans with these pathogens may occur. However, transmission of A. ovis to humans is unclear. The role of R. bursa, a common tick species in sheep and goats in Cyprus (D. Chochlakis, unpub. data), as a vector of other pathogens for humans has been proposed (10). Whether these pathogens include A. ovis is unknown. Thus, laboratory testing of human blood samples should include universal primers against all Anaplasma spp. to avoid missing cases such as the one we report.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Chochlakis D, Ioannou I, Tselentis Y, Psaroulaki A. Human anaplasmosis and Anaplasma ovis variant [letter]. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2010 Jun [date cited]. http://www.cdc.gov/EID/content/16/6/1031.htm

References

- 1.de la Fuente J, Atkinson MW, Naranjo V, Fernandez de Mera IG, Mangold AJ, Keating KA, et al. Sequence analysis of the msp4 gene of Anaplasma ovis strains. Vet Microbiol. 2007;119:375–81. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chochlakis D, Koliou M, Ioannou I, Tselentis Y, Psaroulaki A. Kawasaki disease and Anaplasma sp. infection of an infant in Cyprus. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:e71–3. 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Psaroulaki A, Koliou M, Chochlakis D, Ioannou I, Mazeri S, Tselentis Y. Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:664–6. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31816a0606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chochlakis D, Ioannou I, Sharif L, Kokkini S, Hristophi N, Dimitriou T, et al. Prevalence of Anaplasma sp. in goats and sheep in Cyprus. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:457–63. 10.1089/vbz.2008.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Psaroulaki A, Chochlakis D, Sandalakis V, Vranakis I, Ioannou I, Tselentis Y. Phylogentic analysis of Anaplasma ovis strains isolated from sheep and goats using groEL and mps4 genes. Vet Microbiol. 2009;138:394–400. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dumler JS, Choi KS, Garcia-Garcia JC, Barat NS, Scorpio DG, Garyu JW, et al. Human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1828–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer GH, Abbott JR, French DM, McElwain TF. Persistence of Anaplasma ovis infection and conservation of the msp-2 and msp-3 multigene families within the genus Anaplasma. Infect Immun. 1998;66:6035–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakken JS, Dumler JS. Clinical diagnosis and treatment of human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:236–47. 10.1196/annals.1374.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioannou I, Chochlakis D, Kasinis N, Anayiotos P, Lyssandrou A, Papadopoulos B, et al. Carriage of Rickettsia spp., Coxiella burnetii and Anaplasma spp. by endemic and migratory wild birds and their ectoparasites in Cyprus. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009. Mar 11. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Merino FJ, Nebreda T, Serrano JL, Fernández-Soto P, Encinas A, Pérez-Sánchez R. Tick species and tick-borne infections identified in population from a rural area of Spain. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:943–9. 10.1017/S0950268805004061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]