Abstract

This study seeks to identify how rural adolescents make health decisions and utilize communication strategies to resist influence attempts in offers of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs (ATOD). Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 113 adolescents from rural school districts to solicit information on ATOD norms, past ATOD experiences, and substance offer-response episodes. Rural youths’ resistance strategies were similar to previous findings with urban adolescents – refuse, explain, avoid, and leave (the REAL typology) – while unique features of these strategies were identified including the importance of personal narratives, the articulation of a non-user identity, and being “accountable” to self and others.

Keywords: Rural Health, Adolescents, Substance Use, Resistance Skills Training

Adolescent substance use and abuse remains a national problem (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2009). Historically, public perception has framed substance abuse as a relatively urban phenomenon, with rural communities seen as removed from the social problems of the cities (Van Gundy, 2006). Recent data suggest, however, that substance abuse is a significant problem in rural areas as well (Pruitt, 2009) influenced by low educational attainment and higher rates of unemployment (Lambert, Gale, & Hartley, 2008). In fact, rural youth use more tobacco and methamphetamines than urban youth (Johnston et al., 2009; Roehrich, Meil, Simansky, Davis, & Dunne, 2007) and begin using many drugs at an earlier age (Spoth, Goldberg, Neppl, Trudeau, & Ramisetty-Mikler, 2001). With nearly 20% of the US population residing in rural areas (Pruitt, 2009), addressing substance abuse in rural America requires an extension of the research that goes beyond urban/rural comparisons to allow for descriptive and explanatory studies of rural culture and substance use (Lambert et al., 2008).

The “social” nature of substance use has led to a focus on social processes surrounding substance use, particularly those involved in offer-response episodes (Hansen, 1993; Tobler et al., 2000). In this current study, we aim to increase understanding of the alcohol, tobacco, and other drug refusal strategies employed by youth in rural, Appalachian communities, extending health communication research and practice to this population.

Adolescent Substance Use Prevention

Over the past 20 years there has been considerable energy devoted to developing school-based substance use prevention programming for adolescents (Hopfer et al., 2010). The underlying conceptual model of many of these programs is the social influence model of drug and alcohol use (Cuijpers, 2002; Tobler et al., 2000). This model assumes that adolescents’ substance use is determined by interdependent and overlapping social influences (e.g., parents, peers) exerted through the messages used in drug offers. As a result, it is essential to describe these social processes.

Communication, Adolescent Drug Use, and Social Resistance

In the 1980’s the National Institute on Drug Abuse began funding a number of communication-based prevention efforts (Sypher & Donohew, 1991). One such effort, the Drug Resistance Strategies Project (DRS project), focused specifically on social resistance processes and school-based prevention (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009). Hecht, Miller-Day, and colleagues’ DRS Project has produced a series of studies of social resistance and adolescent drug centered on narrative accounts of adolescent drug offer processes with particular emphasis on understanding the role of cultural factors in those processes. This work spanned elementary, middle, and high school, as well as college populations. It involved narrative interviews, as well as survey research resulting in an intervention for urban youth called the keepin’ it REAL (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009).

Many communication studies have been generated from this original line of research. For example, qualitative interviews with urban youth identified a typology of four consistent resistance strategies used by adolescents across race and gender: Refuse, Explain, Avoid, and Leave (Alberts, Miller-Rassulo, & Hecht, 1991). This typology was validated in other urban samples (Hecht, Alberts, & Miller-Rassulo, 1992; Hecht & Driscoll, 1994). Other studies revealed that urban middle school students were most likely to receive offers from acquaintances (Moon, Hecht, Jackson, & Spellers, 1999), which differed from earlier findings for high school (Alberts, Hecht, Miller-Rassulo, & Krizek, 1992) and college students (Hecht et al., 1992), who tended to receive most offers from family or friends. These studies reported that respondents most frequently employed the simple no (refuse) strategy, with relatively few individuals employing a repertoire of resistance strategies, suggesting the importance of skills training for this group.

Substance prevention research in the field of communication has furthered our understanding of a variety of factors involved in youths’ experiences with substances. The majority of this research, however, focuses on urban youth and may not account for the experiences of rural youth. Rural adolescents in Pennsylvania, for example, are more likely to have used alcohol and chewing tobacco than Pennsylvania’s urban adolescents: 80% of these rural adolescents have tried alcohol and 37% used marijuana at least once by the time they reach 12th grade (Aronson, Feinberg, & Kozlowski, 2009). Thus, we argue that studies like this one are needed in order to expand our understanding of health communication by developing a greater understanding of the issues facing rural youth. The current study seeks to identify the drug resistance strategies reported by rural, Appalachian youth and to provide a description of these youths’ responses to drug offers. Specifically, this study was guided by the following research questions:

-

RQ1

What communication strategies do rural youth use to accept ATOD offers?

-

RQ2

What communication strategies do rural youth use to refuse ATOD offers?

-

RQ3

What differences in strategies emerge when comparing gender and past drug use?

-

RQ4

What reasons do rural youth give for accepting ATOD offers?

-

RQ5

What reasons do rural youth give for refusing ATOD offers?

Methods

Sampling

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with 118 youth from rural, Appalachian schools in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Participants were recruited from schools identified as rural based on one of two main criteria: (a) the school district being located in a “rural” area as determined by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES, n.d.), and (b) the school’s location in a county being considered “Appalachian” according to the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC). Participating schools served a large population of economically disadvantaged students identified by family income being equal to or less than 180% of the United States Department of Agricultural federal poverty guidelines (Ohio Department of Education, 2010). Students identified as disadvantaged ranged between 53% and 61% in the Ohio schools and between 20% and 65% in Pennsylvania schools. Our sample may not be representative of all rural youth; however, our findings may transfer to other, similar populations of rural youth (Polit & Hungler, 1999).

Procedures

Three prevention coordinators from Pennsylvania and one from Ohio were designated as liaisons between the research personnel and the schools to recruit adolescent participants in three phases. Liaisons contacted school decision-makers (e.g., principal, guidance counselor), described the study, and asked for cooperation in recruiting student participants. Each decision-maker was informed that (a) interviews would be audio recorded, (b) the data obtained in the interviews would remain confidential and would be used to develop a rural substance abuse prevention program, (c) all researchers had governmental clearance to work with children, (d) all research activities were supervised by the universities’ Institutional Review Board, and (e) each participating adolescent would receive $5. Students were eligible to participate in the interview process once their parents mailed us a signed parental consent form and once they signed a student assent form. After receiving these items, the liaison and school decision-maker coordinated individual interview sessions.

A multiphase criterion sampling procedure (Patton, 2002) was employed in this study which basically entails selecting cases that meet predetermined criteria of importance and then iteratively collecting more specific information in each sampling phase. Sampling continues until saturation is reached; that is, no new information or new insights are gained (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003). The first stage of recruitment involved a broadly defined criterion for inclusion, recruiting key informants who were middle school adolescents attending school in a rural, Appalachian district. Fifty participants were sampled in the first stage. The second stage involved recruiting rural, Appalachian adolescents who met the foregoing criteria and had experience with drug offers. These participants were purposively selected to provide more specific, in-depth personal experience about rural drug culture, drug offers, drug resistance episodes, and rural drug use scenarios than the first group of participants. In this stage, we recruited 61 participants. The third stage involved extreme case sampling with recruitment of rural adolescent key informants with in-depth experience with personal drug use and/or abuse. We recruited 7 participants who fit these criteria, almost all of whom were on juvenile probation for drug related offenses. Of the 118 interviewed adolescents, three interviews were eliminated from the sample due to technical difficulties with their recording and two were eliminated due to a NCES classification (NCES, n.d.) that was determined to be more suburban than rural. The final sample included 113 participants (male = 62, 55%; female = 51, 45%), with ages ranging from 12–19 years (M = 13.68, SD = 1.37). Slightly over 81% of the interviews were conducted with students in the 7th or 8th grades. Racial demographics for our sample (White = 85.8%; Asian = .9%; mixed race = 6.2%; Latino/a = 5.3%; and African American = .9%) were representative of school districts in the study. One participant did not indicate ethnicity. Forty-six participants were from Ohio and 67 from Pennsylvania, representing 9 different counties (3 Ohio and 6 Pennsylvania), 12 different schools (4 Ohio and 8 Pennsylvania) and 1 alcohol and drug service organization in Pennsylvania..

Interviews

We employed semi-structured interviewing to allow us to maximize the depth of information obtained from each participant while maintaining a structured interview process (Rubin & Rubin, 2004) given the limitations imposed by school-based interviews. A team of 11 interviewers participated in a 4-hour training process which involved reviewing guidelines for ethical research, overviewing interview protocol and procedures, and practicing interviews with feedback.

The semi-structured interview guide prompted students to discuss several topics regarding an interviewee’s (a) perceived identity; (b) hometown and the surrounding area; (c) risky behaviors; (d) ATOD offer-response episodes and/or encounters with ATOD; (e) goals, aspirations, and visions – or “possible selves” – of the future; and (f) parental and sibling opinions regarding substance use. We limited our analysis to the discussion of two topics: risky behaviors and ATOD experiences, including ATOD offers and responses. At the time of the interview each participant completed a face sheet which consisted of demographic information (gender, age, grade, school, ethnicity, and residence history). Following the interviews, a research team member downloaded the audio files to a password protected computer and then sent them out for professional transcription.

Interviews were conducted in private locations within the schools. In most cases, either the adult school contact or the study liaison brought students to their interview site to ensure that the interviewer did not know the students’ names—only their unique identification number. Researchers assured all students their responses would remain confidential, in accordance with Institutional Review Board standards, and the interviewee was permitted to withdrawal from the study at any time. Interviews ranged from 18 – 91 minutes in length. This length is typical of interviews dealing with sensitive topics such as drug use in a school-based setting (Alberts et al., 1991; Botvin et al., 2000).

Interview Analysis

In accordance with procedures set forth by qualitative methodologists, data analysis was ongoing, continuously integrated, and consisted of two distinct phases: the preliminary phase and the substantive phase (Cresswell, 2007).

Preliminary phase

The preliminary phase occurred during the process of conducting the interviews and lasted until all interviews were completed. Case memos were written for each interview, including a description of the interview which summarized key points of interest and identified areas to probe for additional information in future interviews. During this phase researchers discussed these summaries and began a preliminary codebook of emerging concepts. While listening to the audio recording of each interview, team members checked transcripts for accuracy and revised as needed.

Substantive phase

After interviews were completed and transcribed, we began to analyze the data specifically to answer our research questions by commencing with an individual case analysis followed by a cross-case analysis. The individual, within-case analysis proceeded along four main steps: (a) reading each transcript through 2–3 times before reducing it for analysis; (b) inductively identifying and labeling meaningful units of thought (ranging from one sentence to one paragraph) in a process of open coding; (c) organizing these units into meaningful categories of codes; (d) and, adding to and refining code lists.

Early in the coding of individual cases, we sought to assess coding agreement. This not only provided a measure of coding quality, but also allowed us to correct any coding disagreements that arose early in the process and provided consensual agreement on determining definitions of codes for the remaining analysis. With intensive, federally funded projects such as this one, early indications are needed to keep on a tight timetable and avoid wasted resources. Two researchers coded 20% of the meaning units setting an agreement level at .80 or eighty percent agreement. For the first 10% of the meaning units, a simple percent agreement was employed with any disagreements discussed and renegotiated through consensual agreement. Agreement was 95%, exceeding the 80% threshold. Next, an additional 10% of total units were analyzed using the agreed upon coding categories and employing Krippendorff’s alpha (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) as the index of reliability between two independent observers. The intent of calculating agreement was not merely to verify that data are labeled and sorted in exactly the same way but to determine whether or not various researchers and experts would agree with the way those data were labeled and sorted (Woods & Catanzaro, 1988). When new codes were introduced coders met to discuss, clarify, and determine the code definition before proceeding with the analysis. These findings supported the trustworthiness of coding and allowed us to complete coding of all cases before moving on to the cross-case analyses.

The cross-case analysis required the following three steps. First, we compared and contrasted individual cases to identify discrepancies and consistencies across participants’ data. Second, we reduced codes and categories to reflect emerging themes within and across cases. A theme is the thread of meaning that recurs across categories and cases (Baxter, 1991); themes link the underlying meanings across categories (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). Third, we identified exemplars to illustrate and support each theme (Maxwell, 2005). Exemplars are specific illustrations of themes taken directly from the transcripts and used by interpretive researchers to illustrate a connection between the data and the findings. Team members met regularly to conference emerging themes as well as challenge and refine theme classifications.

Nvivo 8 was used to manage and analyze the interview data. Attributes for each participant were added into both Nvivo and SPSS. Attribute analysis in Nvivo 8 consisted of running queries relevant to the study research questions. For example, conducting a search for what resistance strategies were used by females who had never been offered a drug.

Findings

Analyses revealed an array of information on a number of topics related to rural ATOD use and perceptions. The presentation of findings is organized around our guiding research questions.

RQ1: What Communication Strategies do Rural Youth Use to Accept ATOD Offers?

In our sample sixty-five youth (58%) reported being explicitly offered an illegal substance (53% of males and 63% of females) whereas 74 youth (65%) reported having access to illegal substances (66% of males and 65% of females). Communicating acceptance of ATOD offers is a predominantly nonverbal process. Many of the participants in this sample who reported ATOD use did not report elaborate explanations or justifications for their use. They simply accepted what had been offered to them. One young man shared, “Like, you kinda trust ‘em ‘cause they’re a friend. … Most of the time they’s, like, ‘Oh it’s real good, you gotta try this. It’s good.’ So you just, just go right up, take it, and try it (OH009).” When another young lady was offered a beer, she said “‘sure’ and they handed it to me and I drank it” (PA015). To summarize, accepting an offer is often nonverbal process alone (just taking the substance and using it) or a combination of saying “yes” to the offer and then taking the substance.

RQ2: What Communication Strategies do Rural Youth Use to Refuse ATOD Offers?

Resistance strategies identified in previous research conducted by Hecht, Miller-Day and colleagues (see for example, Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009) were used as a-priori codes and sensitizing concepts in this analysis. Importantly, sensitizing concepts provide researchers with an idea of what may be expected in the data and provide guidance but does not dictate the analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Thus, the use of previously identified resistance strategies as codes did not prevent additional resistance strategies from emerging. Indeed, we sought to examine how the repertoire of resistance strategies reported in our sample of rural adolescent culture were similar to or differed from the urban adolescent culture reported in previous research (e.g., Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009; Miller, Alberts, Hecht, Trost, & Krizek, 2000). In the end, after we grouped codes into categories and examined themes in the data (i.e., underlying meanings across categories; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004), resistance strategies reported by youth in our sample fell cleanly into the REAL typology: refuse, explain, avoid, and leave. Particular categories that comprised each strategy, however, showed that rural youth often enacted these strategies in different ways than urban youth. Additionally, in this Appalachian rural sample, differences based on previous substance use were discovered. The following provides a description of these findings.

Refusal strategies: REAL

The REAL typology found in urban narratives encompasses an increasingly complex resistance sequence (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009). The simplest strategy is Refuse, a simple no, with increasing complex strategies of Explain, Avoid and/or Leave. Youth in our sample reported using all four strategies when confronted with offers of alcohol, smoking tobacco, and other drugs (e.g., marijuana, cocaine, pills). When offered chewing tobacco, however, youth only reported using the refuse strategy. Each strategy is detailed below.

Refuse

Refusing offers of illicit substances was reported by males (n = 14) and females (n = 15) and by those who reported previous ATOD use (n = 15) and those who had not previously used (n = 14). Refusal was exemplified by, “I just told him ‘no’ (OH002)”, and “Heck no dude. I ain’t doing no drugs” (OH009). A simple refusal was sometimes used in combination with other types of resistance strategies, such as explaining.

Explain

Explain is defined as providing reasons for refusing a specific offer of ATOD. Sometimes participants offered multiple reasons for resisting ATOD offers. PA064 effectively resisted offers by saying, “If I get caught doing that I’d be dead. I’m like, ‘I’m not doing that cause it’s bad for you.’” Another youth deferred to the law: “She definitely knew I was under age” (PA002). Several shared stories of how they made up an excuse to explain why they could not use ATOD. For example, PA072 suggested, “if you wanna use an excuse just be like, ‘Sorry, dude, I already drank a little bit and I’m good for now.’” He gave another example, “Or if you have a job you could say, ‘I have to get a urine test and I don’t want it to show up in that so I don’t get fired.’” One older youth told people who offered her alcohol that she couldn’t because she was driving (PA078). Reasons participants reported for resisting ATOD offers are more fully reported below.

A few participants (e.g., OH009, PA072, PA077) felt it was very important to be able to give not just any reason, but a “good” explanation for refusing an ATOD offer. One participant responded to the question, “Tell me, what did you say when [you] didn’t do the cigarette?”

I just said, “No dude, I promised my grandpa.” And they said, …”Oh dude, I understand. That’s okay, you don’t have to.” … When I told ‘em, “No, it was a promise to my grandpa,” like, they dropped it. But if it, if I wouldn’t have promised my grandpa or nothin’ … they would’ve keep on buggin’ ya all night. They wouldn’t a stopped. …. (OH009)

Avoid

Avoiding locations where ATOD will likely be present or people who are associated with ATOD is one of the most complex resistance strategies. Avoiding strategies sometimes required fast thinking. PA071 told this story.

I was at a party, and this kid was – he had [cocaine] on him, and he came up to me, and he came up to me, and was like, ‘Oh, yeah, you want to do this with me?’ I would just be like, ‘Yeah, hold on, I’ll be right back. I have to go to the bathroom,’ …and I’ll just avoid him for the rest of the night.

Participants reported employing an avoidance strategy prior to, in anticipation of, and in response to ATOD encounters. For some, keeping away from a situation where ATOD is likely present occurred prior to offer-response episodes; it was proactive avoidance. PA003 said, “Like if I know someone does it [ATOD], I don’t hang out with ‘em-.”

A reactive avoidance strategy happened when participants responded to offer-response situations by ending an acquaintance/friendship with the one offering or using ATOD. For example, one youth told us, “I used to be friends with [her] ‘til I found out she did drugs and stuff” (PA050). PA005 shared, “He was one of my friends, so I cared about him, then he started to get into that stuff [ATOD], and I just … walked away. I don’t see him anymore. At all. Ever.” Strong reactive avoidance to people associated with ATOD may be a useful protective factor for adolescents. Such a reaction curtails teen exposure to ATOD offers. It also changes the peer group surrounding a teen by disassociating from those who are using ATOD.

Leave

Leaving is a straightforward behavior: “I just walked away.” PA046 described a time people using ATOD invaded the recreational space where he and some friends were playing football. He and his friends left the situation by moving to another part of the field. Later, he reported another incident when he, “went out [of the room], but I called my mom and told her to come pick me up.” One time when a stranger offered PA037 a cigarette, she “pushed it out of his hand and ran.” Likewise, when OH032 was offered beer from her cousin, she and her friends “just ran off and told [their cousins’] dad.”

Unique features of rural refusal strategies

While the four refusal strategies of refuse, explain, avoid, and leave were similar to strategies identified in urban samples, unique features emerged for how rural youth enacted the strategies. In particular, the unique features of these strategies among rural youth included the importance of sharing personal narratives when employing an explain strategy, being “accountable” as a motivating factor, and articulating of a non-user identity as either an “explain” or “avoid” strategy for resisting offers.

Telling a story – the narrative form

Rural youth often employed the use of personal stories (narratives) in their answers to describe the resistance process. While stories have been reported in some previous social resistance literature focusing on urban youth, it was not a major feature of the explanation strategy. In this present study, the use of storytelling by rural youth was quite pronounced and stories of vicarious experiences were some of the most common narratives. For OH009 and others, telling a narrative of vicarious experience, offered a compelling excuse for refusing ATOD offers. PA015 shared that she refuses drugs other than alcohol because of an experience when she visited her uncle in Texas. She recalled that two days after she arrived, “He was smoking weed at night and then he sh- shot heroin and he killed his baby, and he killed his wife, and he’s, and he pretty much, he’s pretty much on death row right now” (PA015).

The stories depicted scenarios rife with the negative impacts of drug use on specific others. Main characters in these stories were often older family members and sometimes older friends who learned important lessons about ATOD use from their experiences. Many of the stories described the consequences of ATOD use and included doing poorly in school, difficulty getting a job, regret, wasted years, and deteriorating attractiveness. Other stories we heard had even more serious consequences for their characters, such as death, trouble with the law, paralysis, and family difficulties. Witnessing and/or having knowledge of the characters’ experiences deterred youth from trying particular substances.

Accountability

Another unique feature of rural resistance was the emphasis youth placed on accountability to family. Rural youth in our sample reported that they were accountable for their behavior, suggesting that this was a key reason for them to avoid a substance related situation. Whereas some youth described being accountable to a sibling as personal motivation for avoiding ATOD, others said they were accountable to parents. In fact, several mentioned the effect of parental monitoring in deterring their drug use. For example, one young man stated, “Like, my mom don’t let me go to the park ‘cause she knows what goes on down there. Like people go down there and smoke and everything like that” (OH005). Another youth shared how vigilant his mother was in monitoring him:

Uh, sometimes at, if [Mom], like, thinks I’m, like, out doing something she’ll, when I get home she’ll tell me about it or something like that but if I’m not out, like, with my friends and stuff or walking around if, like, usually it’s just when I’m gone for a couple hours she thinks I’ll do something. (OH002)

Being accountable to parents or other relatives was an important feature of rural youth’s experiences with substances.

Anti-drug use identity

Finally, anti-drug use identity emerged as an important strategy for explaining or avoiding ATOD offers. As a type of explanation in the midst of offer-response episodes, participants said that they were not the type of person who would do drugs. For example, PA041 explained how “people say I am [a druggie] because they think I’m a rocker, but I’m not a rocker or a druggie.” In essence, PA041 was presenting his anti-drug identity as a reason for resisting an offer. Similarly, PA071 explained why he could not accept an offer due to his identity. Whereas PA041 articulated an anti-drug identity, PA071 resisted a substance offer by communicating his identity as one who would not take a handout.

It was just me and him [in the car], and we were just talking, and he pulls out acid, and he’s like, “Oh, you wanna try some?” I was like, “I don’t have any money,” and he was like, “Well, I can give you one for free.” I’m like, “Nah, I’m not gonna take one for free, man. It’s just not who I am, I’m not gonna take one for free.”

Presenting an anti-drug identity also served as a way to avoid offers. Rural youth told us that articulating a clear anti-ATOD use identity to others in social situations made them less likely to offer them substances (i.e., they avoided facing offers by letting their peers now that it was “just not them”). As some of the above excepts connote, substance use can become closely associated with certain people and places. When substance use becomes associated with people, even as an identity, some participants attempt to completely avoid those individuals. Others made a point of articulating a clear non-use identity to their friends, family, and acquaintances. In small, closely knit rural communities, reputations are often widely known and lasting, and this may explain why this strategy appears to be more salient to rural youth. One the youth explained:

People know that I’m just not that ty-, type of girl that would be, do that and if I’m pressured into it, I wouldn’t do it anyways…I just, in any situation, I speak up fer myself. Either that or I have people defending me. (OH022)

Others also presented their position clearly, “I’ve said to people that I don’t like [drugs], like I think they are stupid” (PA004). PA043 shared the following, “Um, well, my one friend, when we walk down the street we scream, like, ‘we’re not potheads and we’re proud of it’ and like we make fun of people that do smoke pot.”

Telling others (friends especially) that youth do not use ATOD is a preemptive avoidance strategy that limits the likelihood that others will even offer these youth illegal substances. Articulating an anti-drug use identity portrays an individual as one who would not do ATOD. It warns others that ATOD offers will be met with resistance and erects barriers against drug dealers and offers. It also engenders social accountability to remain drug-free.

RQ3: What about Gender and Past Drug Use?

We postulated that features of an adolescents’ background – gender and history of drug use – might lead to different resistance strategies. Our reasoning was based on our belief that gender figures prominently in the lives of adolescents, many of whom are experiencing a time of identity exploration (Erikson & Erikson, 1997) and on previous research that suggests gender differences among urban youth and drug use (Johnston et al., 2009). Thus, gender was likely to influence how rural youth respond to drug offers. Similarly, previous research suggests that there may be differences in the social resistance patterns of urban substance users and abstainers (Miller et al., 2000) and we reasoned that these differences and/or other differences might be found among rural youth. Using Nvivo we sorted the sample, first by gender and next by ATOD history (past use/no use) and examined the codes emerging for each group comparing and contrasting the data in each category.

Gender

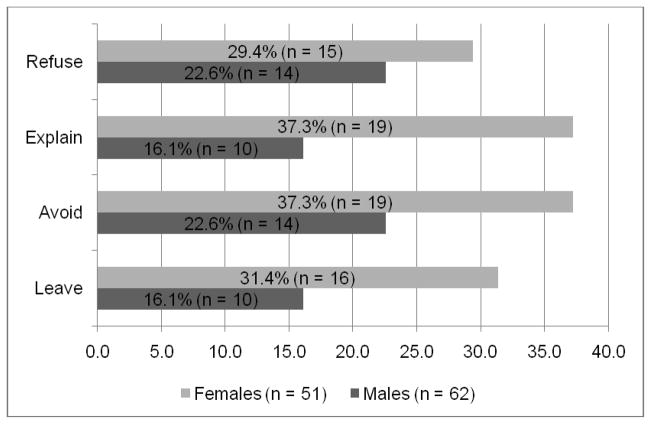

Males in our sample report more substance use than females, 44% compared with 29%, and the use of chewing tobacco was associated exclusively with males. Regarding gender and refusal strategies, in absolute terms females reported using every strategy more frequently than males. Out of all males in our sample, 22.6% refused, 16.1% explained, 22.6% avoided and 16.1% left whereas of all females 29.4% refused, 37.3% explained, 37.3% avoided and 31.4% left. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

REAL Strategies by Gender. This figure illustrates the percentages of males and females who employed each of the four refusal strategies out of the total number of each gender.

Differences between previous ATOD users and non-users

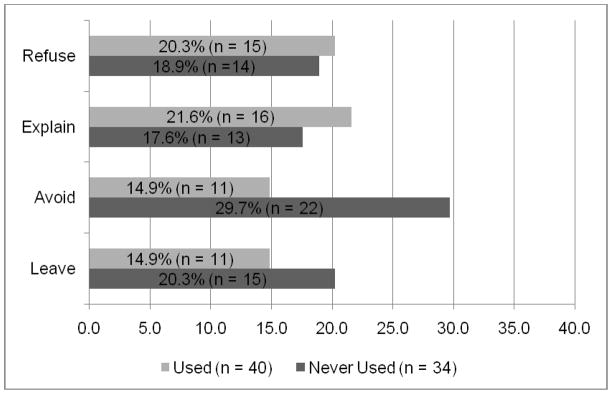

Regarding REAL strategies we also found differences in absolute terms between those who had used ATOD previously and those who had not. For nonusers out of the total number of participants who had been offered or had access to ATOD (n = 74), 18.9% refused, 17.6% explained, 29.7% avoided, and 20.3% left. For those who reported previous use, 20.3% refused, 21.6% left, 14.9% avoided, and 14.9% left. See Figure 2. From analysis of qualitative data associated with these percentages, two discernable patterns of differences emerged between rural adolescents who had used ATOD and those who had not.

Figure 2.

REAL Strategies by ATOD Use. This figure illustrates the percentages of participants who reportedly used or never used ATOD of those offered (n = 74) substances by their refusal strategy.

First, those who reported past use of ATOD employed the storytelling explanation as a resistance strategy differently than non-users when resisting offers. The personal accounts articulated by those with a history of past ATOD use made a point of distinguishing drugs that were “acceptable” for use from drugs unacceptable for use, often failing to classify alcohol as a drug. For example, one participant who drinks alcohol regularly but says she does not want to “do drugs” (despite the fact she has tried several illegal substances) explained, “I don’t [want to use drugs] because my dad, he, like, almost killed my step-mom being on, when he was on drugs” (PA011). Conversely, the personal accounts articulated by those with no previous ATOD use (non-users) provided compelling reasons to refuse all types of ATOD, not distinguishing between acceptable/unacceptable drugs. These participants tended to generalize from the specific substance featured in the story (e.g., alcohol) to all other substances.

The second pattern evident in the qualitative data was that users and non-users tended to present their identity to others in different ways. Logically, non-users most frequently presented a non-use identity as a preemptive avoidance strategy, although a few adolescents who reported past use also presented a non-use identity. PA043 presented a non-marijuana-use-identity by making fun of “people who smoke pot” while simultaneously participating in alcohol consumption. When asked, “What made that situation different that you just took part [in drinking alcohol]?” she responded, “cause it tasted really good. … I mean, like, I was at a party and my boyfriend offered me [the drink] so I took it.” PA043’s non-use identity was substance-specific. Others (e.g., PA041) had only tried ATOD once or twice, perhaps as a young child, and henceforth adopted a non-use identity. Still others shared a conversion narrative in which they once used illegal substances, but then experienced some force compelling them to change, and subsequently reformed and adopted a non-use identity. An example is provided by PA076 who concluded, “I’m a completely different kid.” Whereas, for non-users, an anti-substance use identity applied across all types of substances and seemingly reflected a life-long commitment, for youth with previous ATOD use, expressions of an anti-drug use identity were often substance-specific or were adopted after some compelling experience that convinced them to adopt a non-use identity.

RQ4: What Reasons do Rural Youth give for Accepting ATOD Offers?

Our fourth research question asked about the reasons youth give for accepting ATOD offers. There were two broad categories of reasons for accepting ATOD offers among the rural participants and included personal and social forces. Personal forces signify when trying ATOD accrues some personal benefit, such as a pleasing taste, fun experience, or relaxation. Personal forces included three subcategories – the belief that ATOD use was a normative part of development (“We’re going to cuz we’re kids.” PA053), low levels of risk (“It’s not like a big deal if you do it like once or twice a week or something like that.” PA049), and boredom (“Life is so boring and horrible I have to block it out with drugs and stuff.” PA060). Social forces involved situations when using ATOD provided a social benefit. Subcategories of social forces include establishing or maintaining friendships (“My friends were doing it so I did it.” OH051), impression management (“They try to do it when they’re around girls or whatever.” OH009), and celebration (“I got my first kill [on a hunting trip] … it was a big turkey. So, [my Dad] said, ‘Here you can have a sip of this [alcohol], just a sip for celebration.’” PA010).

Categories of personal and social forces overlap to some degree. For example, boredom might be blamed on a social force like the lack of public entertainment options (“‘Cause it’s such a small town. There ain’t nothing to do here.” OH051) or on a personal force like a lack of ingenuity (“I get bored and … have nobody to hang out with so I just go [into town] with my friends and hang out [smoke marijuana] with them and stuff.” PA049). The categories were divided based on whether or not the primary motivation for ATOD use seemed to be personal or social.

RQ5: What Reasons do Rural Youth give for Refusing ATOD Offers?

Youth provided a number of reasons for resisting substances. Short-term consequences included legal and/or family punishments (“I’d probably get grounded and phone taken away” PA005). Long-term consequences tended to focus on health or cosmetic issues (“I don’t want my teeth to get like that.”; “You can get cancer…” PA004), although some participants mentioned consequences related to their future success, such as getting a job or going to college. Youth who cited being a role model as a reason for refusing substance offers wanted those who looked up to them to learn from their mistakes or to follow their example. OH005 shared that her little sister “wants to be like me when she grows up [so] … I gotta do the best I can all the time because I don’t want her growin’ up, messin’ up.” Some participants refused drugs because of a personal preference (“I just don’t like it.” OH004) whereas others refused offers because of a vicarious or personal negative experience (“My older brother.… got drunk one night and ended up killin’ one my cousins because they were in a car accident and everything.” OH005). Some youth employed several reasons for resisting substance offers.

Discussion

This study adds to health communication research about adolescent drug use by focusing on the social processes of substance use among one sample of rural youth. Drug offers involve a complex and often problematic social situation for youth. As demonstrated in this and previous research (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009; Miller et al., 2000), drug offers typically come from those with whom youth are close, including family and friends. This is likely to be particularly problematic in cultures like those typically found in our rural communities that stress families and close relationships (Scaramella & Keyes, 2001). This makes rural substance offers and responses not only social encounters but often sensitive and complex encounters with close interpersonal or familial relationships. We discuss implications of these findings in terms of reasons adolescents accept or refuse ATOD, refusal strategies used by rural youth, and adolescent substance prevention programs.

Reasons for Accepting or Refusing ATOD Offers

We compared the reasoning process of those accepting and rejecting ATOD offers. We found that accepting ATOD is motivated by both personal and social reasons and is a straightforward communication process. Once youth have decided to use ATOD, communicating their decision is as simple as grabbing a beer bottle, saying “yes,” or taking a hit on a joint being passed around a circle.

One particularly interesting finding is that boredom appears to be an important motivator for accepting offers of ATOD in this rural sample. Youth from our sample reported experimenting with ATOD as a way to pass the time and as an after-school activity with friends. While this is similar in some ways to urban youth who often say the use drugs to “kill time” (Miller et al., 2000), it is exacerbated in rural communities by factors such as few entertainment options potentially putting rural youth at higher risk to initiate substance use (Scaramella & Keyes, 2001).

Rural youth cite many reasons for refusing ATOD offers including short and long term consequences of use, personal reasons, negative vicarious stories, and being a role model for others. Some of these factors are likely to be especially relevant to rural youth. Being a role model to younger siblings or others in a community, for example, may be particularly salient to rural youth who live among a “fishbowl” community where “everyone knows them” and their reputations will stay with them indefinitely. Narratives were also cited as a reason for refusing substance offers by rural youth in our sample. Given that the likelihood that rural youth know the majority of community members, when negative consequences result from ATOD use/abuse, the story takes on meaning. It is not a stranger who was hit by a car, sentenced to jail, or committed a violent crime; it is a neighbor, acquaintance, cousin, or friend. These narratives persuaded some rural youth to refuse substance offers.

Resistance Strategies of Rural Youth

Our analyses revealed that rural adolescents from Pennsylvania and Ohio employed the same four primary resistance strategies – refuse, explain, avoid, and leave – identified in previous research among urban youth (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009), but enacted resistance strategies in different ways than urban youth. The REAL resistance typology appears to apply broadly across urban and rural youth samples in addition to spanning early adolescence into early adulthood. Our study adds crucial knowledge about the transportability of the REAL topology to rural, Appalachian settings and demonstrates that – at least in terms of the resistance strategies taught in prevention curricula – that one size may not fit all, but it may be close. REAL resistance strategies can be taught across urban and rural contexts, but practitioners should be aware that the ways rural, Appalachian youth and urban youth enact these strategies differ in culturally important ways.

Youth in our sample emphasized the importance of narratives, accountability, and presenting an anti-use identity. Whereas explanations were important for youth in previous research as well as this study, explanations provided by rural, Appalachian youth often took a narrative form. Participants stressed the importance of telling “good” or appropriate stories in explanation for why they would choose not to use a substance. Fisher’s (1985) narrative paradigm argues that humans use a rationality including “good reasons” for assessing stories and whether they should accept a given story as a basis for decisions and actions. The findings in this study suggest that rural adolescents act on the basis of this rational and construct narratives that will count for their audiences as a plausible reason for resisting an offer. Of course, not every explanation had to be backed by a story, but it was common. In studies of urban youth, explanations consisted of expressing a fear of consequences, sharing anti-drug attitudes, and articulating a non-use identity (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009). Narratives were not among explanatory tactics used among urban samples.

Another example of how rural refusal tactics differed was in the avoidance strategy. Youth in our sample stressed that being accountable to parents and others factored into their decisions to avoid substances. An anti-use identity also factored into youths’ avoidance of drug offers. In urban samples, presenting a non-use identity was only reported as an explain strategy. In our sample of rural youth, articulating a non-use identity was a both a reactive explanation and a proactive avoidance tactic.

Gender Differences in the Resistance Processes

The gender differences reported for substance use in our analysis align with work done in national samples showing greater use among males (Johnston et al., 2009). In addition, females reported proportionally more of every resistance strategy. Since our study was primarily qualitative, it was not designed to detect statistically significant differences. Future research using larger samples and methods designed to examine difference might better determine whether rural males and females differentially use REAL resistances strategies. Looking at the interaction between gender and location (rural vs. urban) might also be a useful future direction.

Differences by ATOD Use

Another trend to investigate in future research is which resistance strategies predict nonuse. Although we do not claim statistically significant differences, in our data more nonusers reported avoiding and leaving offer-response situations than users, which suggests that avoiding situations where drugs are present or reacting to a substance offer by avoiding or leaving may be more effective resistance strategies than refusing and explaining. One potential warrant for the trend in our data would be that avoiding – especially preemptive avoiding – and leaving potentially limits exposure to the pressure of offer-response episodes whereas refusing and explaining do not. Thus, by minimizing exposure to offers, youth who avoid and leave situations have less chances of “giving in” to pressure or adopting attitudes that might motivate ATOD use. Another warrant is that avoiding offers – both in response and prior to offer-response episodes – may alter a youth’s friendship network. Some youth in our sample avoided by ending friendships or staying away from particular people who used ATOD. Those who avoided and left situations may be opting out of friendships with “risky” peers. Given the high correlation between peer drug use and personal use (Stormshak, Comeau, & Shepard, 2004), these strategies may have an indirect effect by influencing which peers become friends and which do not. Which strategies were most predictive of nonuse was not tested in this data, but such a study could shed light on the relative contribution of each resistance skill in predicting nonuse.

Implications of Findings for Substance Use Prevention

In addition to expanding health communication research to a new population, the most prominent application of our findings is in the area of ATOD prevention curricula. In their discussion of rural adolescent substance use, Scaramella and Keyes (2001) reported that there were only three theoretically based prevention programs which even considered rural populations in addition to urban populations, and none of these were evidence-based programs. Thus, there is a need to create prevention curricula specifically for rural populations or adapt existing curricula to include the rural experience. Some researchers have begun to develop such programs. For example, a revised version of Project ALERT has been tested with a sample of rural and non-rural youth with studies showing inconclusive program effects (Ellickson, McCaffrey, Ghosh-Dastidar, & Longshore, 2003; St. Pierre, Osgood, Mincemoyer, Kaltreider, & Kauh, 2005). Another evidence-based prevention program, keepin’ it REAL or kiR (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009) uses the REAL system of resistance as its centerpiece. kiR is one of the most cost effective programs (Miller & Hendrie, 2009) and is believed to be the most widely disseminated with its adoption and implementation by D.A.R.E. America Our finding that the REAL typology transports to a population of rural, Appalachian youth suggests that it may transcend geographic location and could be incorporated into a universal prevention program. Future research might be designed to directly test these inductively derived similarities and differences. Findings supporting rural and urban differences may ultimately inform prevention programs, such as D.A.R.E., that have separate urban and rural versions.

Summary

In conclusion, this study fills and important gap in our knowledge of the social processes of substance use by extending this research to rural, Appalachian youth. While we often see health disparities in terms of SES, race, or nation-states (Ndiaye, Krieger, Warren, Hecht, & Okuyemi, 2008), clearly rural communities have inequitable access to health services and poorer health outcomes (Ndiaye et al., 2008). Even more pertinently, rural youth appear to be more at risk for many substances, particularly the gateway ones (Roehrich et al., 2007).

In light of these cultural and health outcome differences, it is somewhat comforting that the REAL model appears to transport to our rural sample from urban communities. At the same time, important differences between rural and urban youth are suggested by these analyses that have important implications for theory and practice. Differences in the form and content of resistance strategies suggest that health message design theories must consider location as an important cultural variable. Future research that directly compares rural, suburban, and urban youth is needed to clarify any cultural differences and allow for a more nuanced model of the social resistance as well as the targeting and tailoring (Roberto, Krieger, & Beam, 2009) of prevention messages.

Acknowledgments

This paper was presented May 29, 2009 at the Society for Prevention Research annual meeting in Washington, D.C. The authors thank the students and schools who participated in this study. We are also grateful to the participants for sharing their experiences and to other members of the research team for their help with this project: M. Colby, T. Deas, A. Dossett, T. Hipper, S. Hopfer, J. Moreland, and A. Pezalla. This publication was supported by Grant Number R01DA021670 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to The Pennsylvania State University (Michael Hecht, Principal Investigator). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Jonathan Pettigrew, Department of Communication Arts and Sciences at Penn State University.

Michelle Miller-Day, Department of Communication Arts and Sciences at Penn State University.

Janice Krieger, School of Communication at The Ohio State University.

Michael L. Hecht, Department of Communication Arts and Sciences at Penn State University.

References

- Alberts JK, Hecht ML, Miller-Rassulo M, Krizek RL. The communicative process of drug resistance among high school students. Adolescence. 1992;27:203–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts JK, Miller-Rassulo M, Hecht ML. A typology of drug resistance strategies. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 1991;19:129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson KR, Feinberg ME, Kozlowski L. Alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among youth in rural Pennsylvania. Center for Rural Pennsylvania; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.rural.palegislature.us/ATOD2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach CF, Silverstein LB. Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York: New York University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LA. Content analysis. In: Montgomery BM, Duck S, editors. Studying Interpersonal Interaction. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1991. pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Scheier LM, Williams C, Epstein JA. Preventing illicit drug use in adolescents: Long-term follow-up data from a randomized control trial of a school population. Addictive Behavior. 2000;5:769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P. Effective ingredients of school-based drug prevention programs: A systematic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Longshore DL. New inroads in preventing adolescent drug use: Results from a large-scale trial of Project ALERT in middle schools. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1830–1836. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH, Erikson JM. The life cycle completed. New York, NY: W. W. Norton; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WR. The narrative paradigm: In the beginning. Journal of Communication. 1985;35:74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB. School-based alcohol prevention programs. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1993;17:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Krippendorff K. Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures. 2007;1:77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Alberts JK, Miller-Rassulo M. Resistance to drug offers among college students. International Journal of the Addictions. 1992;27:995–1017. doi: 10.3109/10826089209065589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Driscoll G. A comparison of the communication, social, situational, and individual factors associated with alcohol and other drugs. International Journal of the Addictions. 1994;29:1225–1243. doi: 10.3109/10826089409047939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Miller-Day M. The drug resistance strategies project: Using narrative theory to enhance adolescents’ communication competence. In: Frey L, Cissna K, editors. Routledge handbook of applied communication. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. pp. 535–557. [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer S, Davis D, Kam JA, Shin Y, Elek E, Hecht ML. A review of elementary school-based substance use prevention programs: Identifying program attributes. Journal of Drug Education. 2010;40:11–36. doi: 10.2190/DE.40.1.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2008. NIH Publication No. 09-7401. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/overview2008.pdf.

- Lambert D, Gale JA, Hartley D. Substance abuse by youth and young adults in rural America. Journal of Rural Health. 2008;24:221–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JA. Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miller T, Hendrie D. DHHS Pub. No. [SMA] 07-4298. Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009. Substance abuse prevention dollars and cents: A cost-benefit analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Alberts JK, Hecht ML, Trost M, Krizek RL. Adolescent relationships and drug use. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moon DG, Hecht ML, Jackson KM, Spellers R. Ethnic and gender differences and similarities in adolescent drug use and the drug resistance process. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34:1059–1083. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039397. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/10826089909039397. [DOI] [PubMed]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Identification of Rural Locales. n.d Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/rural_locales.asp.

- Ndiaye K, Krieger JR, Warren JW, Hecht ML, Okuyemi K. Health disparities and discrimination: Three perspectives. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice. 2008;2:51–71. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.2-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohio Department of Education. Data for Free and Reduced Price Meal Eligibility (MR81) 2010 Retrieved from http://education.ohio.gov/GD/Templates/Pages/ODE/ODEDetail.aspx?page=3&TopicRelationID=828&ContentID=13197&Content=79922.

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Polit DF, Hungler BP. Nursing Research. Principles and Methods. 6. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt LR. The forgotten fifth: Rural youth and substance abuse. Stanford Law and Policy Review. 2009;20:259–304. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto AJ, Krieger JL, Beam MA. The effects of targeting and tailoring on prevention messages for Hispanics. Journal of Health Communication. 2009;14:525–540. doi: 10.1080/10810730903089606. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730903089606. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Roehrich L, Meil W, Simansky J, Davis W, Dunne R. Substance abuse in rural Pennsylvania: Present and future. Center for Rural Pennsylvania; 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.rural.palegislature.us/substance_abuse07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin HJ, Rubin I. Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. New York, NY: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Keyes AW. The social contextual approach and rural adolescent substance use: Implications for prevention in rural settings. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001;4:231–251. doi: 10.1023/a:1017599031343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Goldberg C, Neppl T, Trudeau L, Ramisetty-Mikler S. Rural-urban differences in the distribution of parent-reported risk factors for substance use among young adolescents. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;14:609–623. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Pierre TL, Osgood DW, Mincemoyer CC, Kaltreider DL, Kauh TJ. Results of an independent evaluation of Project ALERT delivered in schools by cooperative extension. Prevention Science. 2005;6(2):305–317. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Comeau CA, Shepard SA. The relative contribution of sibling deviance and peer deviance in the prediction of substance use across middle childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:635–649. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047212.49463.c7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JACP.0000047212.49463.c7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sypher HE, Donohew RL. Communication and drug abuse prevention research. Health Communication. 1991;3:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler NS, Roona MR, Ochshorn P, Marshall DG, Streke AV, Stackpole KM. School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;20:275–336. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gundy K. Substance abuse in rural and small town America (Reports on Rural America Volume 1, Number 2) 2006 Retrieved from Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire: http://www.carseyinstitute.unh.edu/publications/Report_SubstanceAbuse.pdf.

- Woods NF, Catanzaro M. Nursing research: Theory and practice. Saint Louis, MO: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]