Abstract

Hepatic involvement of amyloidosis is common. Diffuse infiltration with hepatomegaly is a usual radiologic finding of hepatic amyloidosis. To our knowledge, this is the first case of amyloidosis involving the liver that presented as a mass.

Keywords: Amyloidosis, Computed tomography (CT)

INTRODUCTION

Amyloidosis is a pathological process encompassing a spectrum of disease that results from the extracellular deposition of fibrillar amyloid protein (1), which can involve any organ singly or in conjunction with other organs and can do so in the form of a focal, tumor-like lesion, or an infiltrative process (2). Although it is usually seen in a systemic form, 10-20% of cases can be localized (3). In both primary and secondary amyloidosis, the most commonly involved organ system is the gastrointestinal system, with the colon being the most frequently involved organ (2). Amyloidosis involving the liver is also common, and the radiologic findings are also nonspecific. Diffuse infiltration is the rule, which causes decreased attenuation at computed tomography (CT) and hepatomegaly (2). To our knowledge, cases of amyloidosis involving the liver being presented as a mass have not been described previously. Here we report a case of primary hepatic amyloidosis that presented as a mass.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old woman was referred to our institution with general weakness and fever for a day. She had been treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy over the last 20 years due to recurrent multiple myeloma in the right zygoma, sternum, and the posterior arch of T4 vertebra. Physical examination and routine laboratory test results were normal.

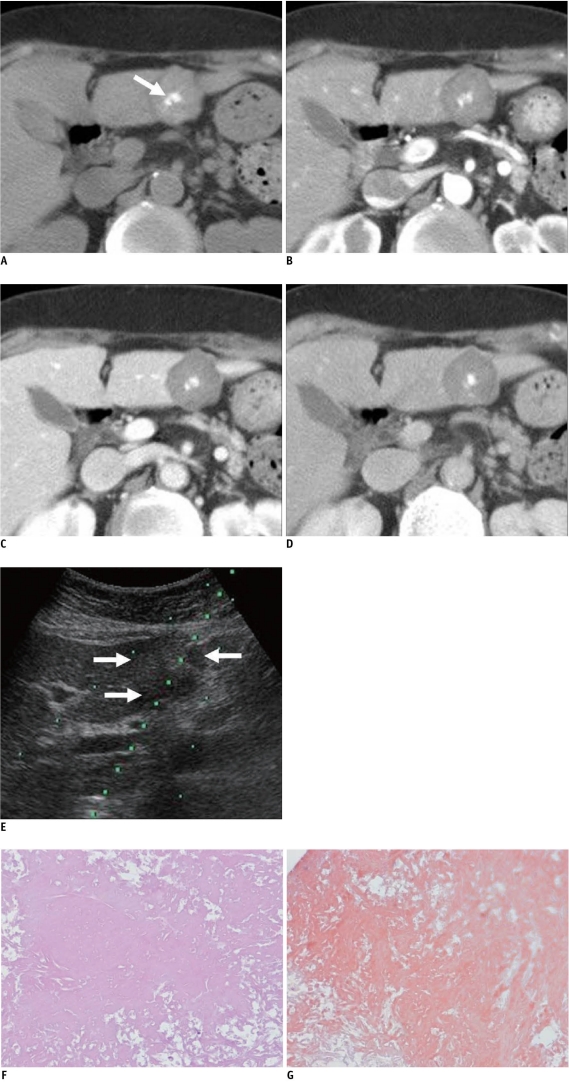

Dynamic CT of the abdomen was performed with a 128-MDCT scanner (SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens, Muenchen, Germany). After unenhanced images were obtained, dynamic three-phase imaging was begun after the start of injection of the contrast medium. Unenhanced CT revealed three high density lobulating masses with central calcification in the dome and segment 3 of the liver. The largest one, which was in segment 3 of the liver, was about 3 cm in diameter (Fig. 1A). The attenuation of all three masses in the unenhanced CT was 88 HU (Hounsfield unit). The masses showed nearly the same attenuation in each phase compared to that of unenhanced CT (Fig. 1B-D). The differential diagnoses including multiple myeloma involvement, an inflammatory pseudotumor, and an unusual pattern of metastases from the other primary malignancy.

Fig. 1.

73-year-old woman with hepatic amyloidosis.

A. Unenhanced CT shows high density lobulating mass with central calcification (arrow) in segment 3 of liver. B-D. Mass shows very poor delayed contrast enhancement on arterial (B), portal venous (C) and delayed (D) phase image. E. US image during needle biopsy indicates mild heterogeneous echoic mass on segment 3 of liver (arrows). F, G. Microscopically, diffuse amyloid deposits are present without viable hepatocyte (F, Hematoxylin & Eosin staining, original magnification × 200), and Congo red stain is positive (G).

On ultrasonography (US), the masses showed mild heterogeneous echotexture (Fig. 1E). US-guided biopsy of the mass in segment 3 of the liver was performed with an 18 gauge gun-biopsy needle. Microscopically, diffuse amyloid deposits were found without viable hepatocyte (Fig. 1F), and the Congo red stain was positive (Fig. 1G).

DISCUSSION

Amyloidosis is an uncommon disease that results from the extracellular deposition of amorphous, fibrillar protein. Amyloid is defined as a substance which stains positively with Congo red, exhibits apple green birefringence by polarization microscopy, shows aggregations of approximately 10 nm wide fibrils on electron microscopy, exhibits a β-pleated sheet configuration on radiographic analysis, and shows resistance to proteases other than pronase (4). Progressive deposition of amyloid compresses and replaces normal tissue, and this leads to organ dysfunction and a wide variety of clinical syndromes, some of which have severe pathophysiological consequences (5).

Amyloidosis is usually observed in a systemic form although 10-20% of cases are localized (3). According to the World Health Organization's classification, this is based on the structure of the variable fibrillar protein constituent (6). The vast majority of amyloidoses are either of the primary or secondary type (2). In primary amyloidosis, the characteristic fibrillar protein is a fragment of the variable immunoglobulin light (and/or rarely heavy) chain and thus is different from patient to patient. In contrast, the precipitating protein in secondary amyloidosis is always the amino acid terminus of the acute phase protein serum amyloid A (SAA) and is identical in all patients.

The primary amyloidosis has been associated with a monoclonal plasma cell dyscrasia, as at least 30% of those patients will eventually progress to multiple myeloma. Median survival time for patients with amyloidosis is 1.5 years (7-9). Secondary amyloidosis is a result of chronic inflammatory disease (Crohn's disease, adult or juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Reiter's syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, familial Mediterranean fever, Sjögren's syndrome, dermatomyositis, vasculitis, chronic osteomyelitis, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and so on) and has a median survival of 4.5 years (10, 11). According to the above classification, our case belongs to the primary hepatic amyloidosis.

Amyloid protein deposition can be seen in a variety of organs, although it is more frequently observed in the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and heart (1). In both primary and secondary amyloidosis, the most commonly involved organ system is the gastrointestinal system, with the colon being the most frequently involved organ (2). Although hepatic involvement is also common in patients with amyloidosis, the clinical manifestations of hepatic involvement are usually mild (5). Symptomatic involvement, including rupture, portal hypertension or hepatic failure, is rare (12-14). Hepatomegaly and a borderline abnormal liver function test are the most frequent findings in patients with hepatic amyloidosis (5).

Radiological findings of hepatic involvement are non-specific with heterogeneous echogenicity on US, diffuse or focal regions of decreased parenchymal attenuation with or without extensive calcification on CT or on MRI, a significantly increased signal intensity on T1-weighted images without a significantly altered signal intensity on T2-weighted images (14-18). Kim et al. (5) postulated that asymmetric hepatomegaly of a triangular shape with an apex at the falciform ligament and heterogeneous attenuation may help to differentiate amyloidosis from other infiltrative disease (5).

In our case, only three high density lobulating masses with central calcification were seen in the liver on unenhanced CT without asymmetrical hepatomegaly and heterogeneous attenuation of the liver in the dynamic phase. And, because of the progression deposition of the amyloid compress and the replacement of normal hepatocytes, the masses showed very poor delayed contrast enhancement in the dynamic phase. Secondary calcification of amyloid deposits is suggestive of amyloidosis, irrespective of the involved site (19). To our knowledge, amyloidosis involving the liver being presented as a mass has not been described previously.

Both the clinical and imaging presentations of amyloidosis are usually varied and non-specific, which may cause a delay in diagnosis and appropriate treatment changes. A biopsy is nearly always required for a proper diagnosis. We should consider that hepatic amyloidosis is usually presented as diffuse infiltration and hepatomegaly, but very rarely may appear as unusual focal masses.

References

- 1.Kim MS, Ryu JA, Park CS, Lee EJ, Park NH, Oh HE, et al. Amyloidosis of the mesentery and small intestine presenting as a mesenteric haematoma. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:E1–E3. doi: 10.1259/bjr/13509947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Georgiades CS, Neyman EG, Barish MA, Fishman EK. Amyloidosis: review and CT manifestations. Radiographics. 2004;24:405–416. doi: 10.1148/rg.242035114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott PP, Scott WW, Jr, Siegelman SS. Amyloidosis: an overview. Semin Roentgenol. 1986;21:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0037-198x(86)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenner GG. Amyloid deposits and amyloidosis. The betafibrilloses (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1283–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198006053022305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SH, Han JK, Lee KH, Won HJ, Kim KW, Kim JS, et al. Abdominal amyloidosis: spectrum of radiological findings. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:610–620. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(03)00142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO-IUIS Nomenclature Sub-Committee. Nomenclature of amyloid and amyloidosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71:105–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gertz MA, Kyle RA. Amyloidosis with IgM monoclonal gammopathies. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:325–328. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2003.50060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joss N, McLaughlin K, Simpson K, Boulton-Jones JM. Presentation, survival and prognostic markers in AA amyloidosis. Qjm. 2000;93:535–542. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.8.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasqualetti P, Casale R. Risk of malignant transformation in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Biomed Pharmacother. 1997;51:74–78. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(97)87730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maniatis A. Pathophysiology of paraprotein production. Ren Fail. 1998;20:821–828. doi: 10.3109/08860229809045179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhodapkar MV, Merlini G, Solomon A. Biology and therapy of immunoglobulin deposition diseases. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1997;11:89–110. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70417-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gertz MA, Kyle RA. Hepatic amyloidosis: clinical appraisal in 77 patients. Hepatology. 1997;25:118–121. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gastineau DA, Gertz MA, Rosen CB, Kyle RA. Computed tomography for diagnosis of hepatic rupture in primary systemic amyloidosis. Am J Hematol. 1991;37:194–196. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830370312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monzawa S, Tsukamoto T, Omata K, Hosoda K, Araki T, Sugimura K. A case with primary amyloidosis of the liver and spleen: radiologic findings. Eur J Radiol. 2002;41:237–241. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki S, Takizawa K, Nakajima Y, Katayama M, Sagawa F. CT findings in hepatic and splenic amyloidosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1986;10:332–334. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198603000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennan NM, Evans C. Case report: hepatic and splenic calcification due to amyloid. Clin Radiol. 1991;44:60–61. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs JE, Birnbaum BA, Furth EE. Abdominal visceral calcification in primary amyloidosis: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 1997;22:519–521. doi: 10.1007/s002619900253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson L, Hemmingsson A, Ericsson A, Jung B, Sperber G, Thuomas KA, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in primary amyloidosis. Acta Radiol. 1987;28:13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coumbaras M, Chopier J, Massiani MA, Antoine M, Boudghene F, Bazot M. Diffuse mesenteric and omental infiltration by amyloidosis with omental calcification mimicking abdominal carcinomatosis. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:674–676. doi: 10.1053/crad.2000.0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]