Abstract

Marine animals contain various carotenoids that show structural diversity. These marine animals accumulate carotenoids from foods such as algae and other animals and modify them through metabolic reactions. Many of the carotenoids present in marine animals are metabolites of β-carotene, fucoxanthin, peridinin, diatoxanthin, alloxanthin, and astaxanthin, etc. Carotenoids found in these animals provide the food chain as well as metabolic pathways. In the present review, I will describe marine animal carotenoids from natural product chemistry, metabolism, food chain, and chemosystematic viewpoints, and also describe new structural carotenoids isolated from marine animals over the last decade.

Keywords: carotenoids, marine animals, metabolism, food chain, chemosystematic

1. Introduction

Since the first structural elucidation of β-carotene by Kuhn and Karrer in 1928-1930, about 750 naturally occurring carotenoids had been reported as of 2004 [1]. Improvements of analytical instruments such as NMR, MS, HPLC, etc., have made it possible to perform the structural elucidation of very minor carotenoids in nature [2,3,4].

Marine animals contain various carotenoids that show structural diversity [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Among the 750 reported carotenoids found in nature, more than 250 are of marine origin. In particular, allenic carotenoids, except for neoxanthin and its derivatives, and all acetylenic carotenoids originate from marine algae and animals [1].

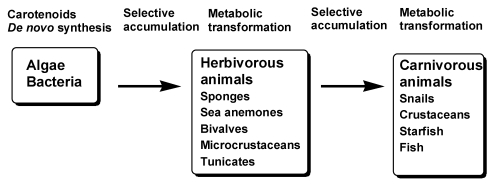

In general, animals do not synthesize carotenoids de novo, and so those found in animals are either directly accumulated from food or partly modified through metabolic reactions [5,6,7,8,9], as shown in Figure 1. The major metabolic conversions of carotenoids found in animals are oxidation, reduction, translation of double bonds, oxidative cleavage of double bonds, and cleavage of epoxy bonds.

Up until 2001, marine animal carotenoids were reviewed by Liaaen-Jensen [5,6], Matsuno [7,8], and Matsuno and Hirao [9]. Since then, there have been no reviews of carotenoids in marine animals. The present review describes progress in the field of carotenoids in marine animals over the last decade.

Figure 1.

Accumulation and metabolism of carotenoids in marine animals through food chain.

2. Porifera (Marine Sponges)

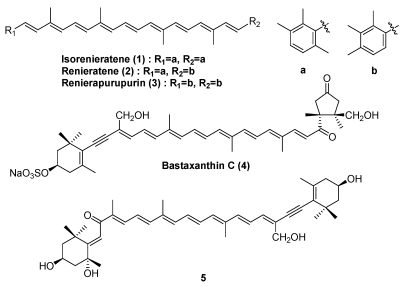

Characteristic carotenoids in marine sponges are shown in Figure 2. Many marine sponges are brilliantly colored due to the presence of carotenoids. Sponges are filter feeders and are frequently associated with symbionts such as microalgae or bacteria [6]. The characteristic carotenoids in sponges are aryl carotenoids such as isorenieratene (1), renieratene (2), and renierapurpurin (3) [6,7]. More than twenty aryl carotenoids have been reported in sponges [1]. Except for sea sponges, aryl carotenoids are found only in green sulfur bacteria [1,6]. Therefore, aryl carotenoids in sponges are assumed to originate from symbiotic bacteria [6,7]. Novel carotenoid sulfates having an acetylenic group, termed bastaxanthins (4), were isolated from the sea sponge Ianthella basta [1]. Recently, a new acetylenic carotenoid (5) was isolated from the marine sponge Prianos osiros [10]. Based on the structural similarity, bastaxanthins and compound 5 were assumed to be metabolites of fucoxanthin originating from microalgae.

Figure 2.

Characteristic carotenoids in marine sponges.

3. Coelenterata (Sea Anemones)

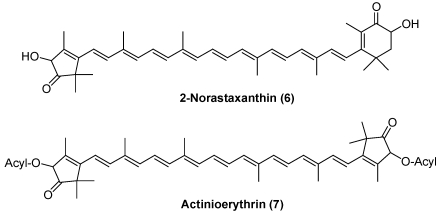

Astaxanthin, which originates from dietary zooplankton, was found in some jelly fish. Peridinin, pyrrhoxanthin, and diadinoxanthin were found in some corals [11]. They originate from symbiotic dinoflagellates. Unique nor carotenoids, 2-nor-astaxnthin (6) and actinioerythrin (7), have been reported in the sea anemones Actinia equina and Tealia felina [1] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Characteristic carotenoids in sea anemones.

4. Mollusca (Mollusks)

Many chitons are herbivorous and feed on attached algae. Major carotenoids found in chitons are lutein, zeaxanthin, fucoxanthin, and their metabolites [12].

Abalone, Haliotis discus discus, and turban shell, Turbo cornutus, feed on brown and red algae. Carotenoids found in these shells are β-carotene, α-carotene, zeaxanthin, lutein, and fucoxanthin [11].

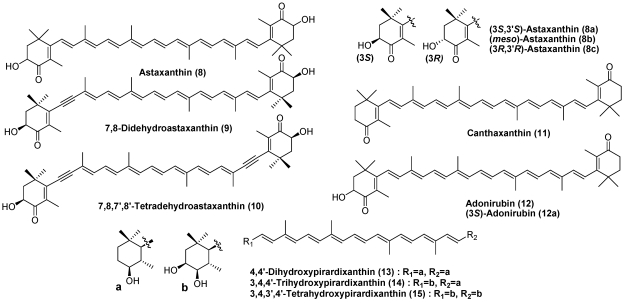

On the other hand, many sea snails are carnivores. The triton Charonia sauliae feeds on starfish. Therefore, astaxanthin (8), 7,8-didehydroastaxanthin (9), and 7,8,7′,8′-tetradehydroastaxanthin (10), characteristic carotenoids found in starfish, were isolated as major carotenoids in triton. Astaxanthin (8), originating from dietary microcrustaceans, was found to be a major carotenoid in the whelk Buccinum bayani. Alternatively, Drupella fragum preys upon corals. Thus, peridinin and diadinoxanthin are present as major carotenoids in this sea snail [11]. Carotenoids in sea snails well reflect their diet.

Canthaxanthin (11), (3 S)-adonirubin (12a), and (3S,3′S)-astaxanthin (8a) were found to be major carotenoids in the spindle shell Fushinus perplexus [13]. Furthermore, a series of carotenoids with a 4-hydroxy-5,6-dihydro-β-end group and/or 3,4-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-β-end (13-15) were isolated from Fushinus perplexus [13] (Figure 4). They were assumed to correspond to reduction metabolites of canthaxanthin (11), (3S)-adonirubin (12a), and (3S,3′S)-astaxanthin (8a).

Sea slugs and sea hares also belong to Gastropoda. They are herbivorous and feed on brown and red algae. Several apocarotenoids have been reported in sea slugs and sea hares [1]. A series of 8′-apocarotenal and 8′-apocarotenols derived from β-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin were found in the sea hare Aplysia kurodai [14]. They are oxidative cleavage products of the polyene chain at C-8 in C40 skeletal carotenoids [14].

Bivalves (oyster, clam, scallop, mussel, ark shell, etc.) contain various carotenoids that show structural diversity [3,6]. Bivalves accumulate carotenoids obtained from their dietary microalgae and modify them through metabolic reactions. Many of the carotenoids present in bivalves are metabolites of fucoxanthin, diatoxanthin, diadinoxanthin, and alloxanthin [3,6], which originate from microalgae.

Figure 4.

Characteristic carotenoids in sea snails.

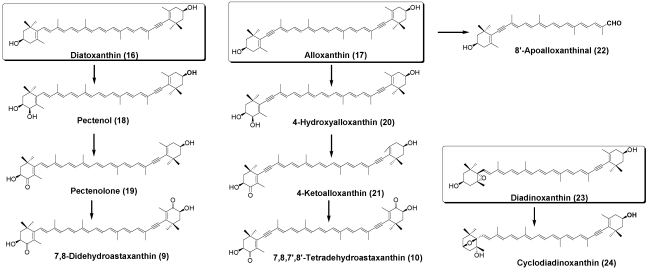

Oxidative metabolites of diatoxanthin (16) and alloxanthin (17), such as pectenol (18), pectenolone (19), 4-hydroxyalloxanthin (20), and 4-ketoalloxanthin (21), are distributed in scallops and ark shells [3,6,7]. 8′-Apoalloxanthinal (22), which is an oxidative cleavage product of alloxanthin, was also found in bivalves [15] (Figure 5).

A novel 3,6-epoxy derivative of diadinoxanthin (23), named cycloidadinoxanthin (24), was also isolated from the oyster [16] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Metabolites of diatoxanthin, alloxanthin, and diadinoxanthin in bivalves.

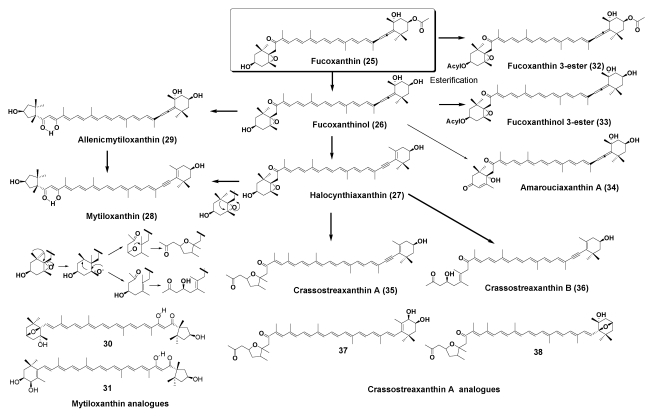

Fucoxanthin (25) and its metabolites fucoxanthinol (26) and halocynthiaxanthin (27) were found to be widely distributed in oysters and clams [3,6,7].

Mytiloxanthin (28), which has a unique enol hydroxy group at C-8′ in the polyene chain and a 3′-hydroxy-6′-oxo-κ-end group, is a characteristic carotenoid in marine mussels and oysters [6,7]. Furthermore, three mytiloxanthin analogues containing an allenic end group (29), a 3,6-epoxy-end group (30), and a 3,4-dihydroxy-β-end group (31) were isolated from the oyster [16,17]. Compound 29, termed allenic mytiloxanthin, was assumed to be a metabolic intermediate from fucoxanthinol to mytiloxanthin.

Some edible clams have a bright orange or red color due to the presence of carotenoids. Fucoxanthin 3-ester (32) and fucoxanthinol 3-ester (33) were found to be major carotenoids in Mactra chinensis [18], Ruditapes philippinarum, and Meretrix petechialis [19]. Amarouciaxanthin A (34) and its ester were also identified as major carotenoids in Paphia amabills and Paphia amabillis [20].

Other metabolites of fucoxanthin, crasssostreaxanthin A (35) and crassostreaxanthin B (36), were isolated from the Japanese oyster Crassostrea gigas [21]. Tode et al. demonstrated that crassostreaxanthin B could be converted from halocynthiaxanthin by bio-mimetic chemical reactions [22,23]. Further studies of carotenoids in marine animals revealed that crassostreaxanthin A, crassostreaxanthin B, and their 3-acetates were widely distributed in marine bivalves [16,17]. Moreover, two crassostreaxanthin A analogues, 37 and 38, were isolated from the oyster as minor components [16,17]. Metabolic pathways of fucoxanthin in bivalves are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Metabolic pathways of fucoxanthin in bivalves.

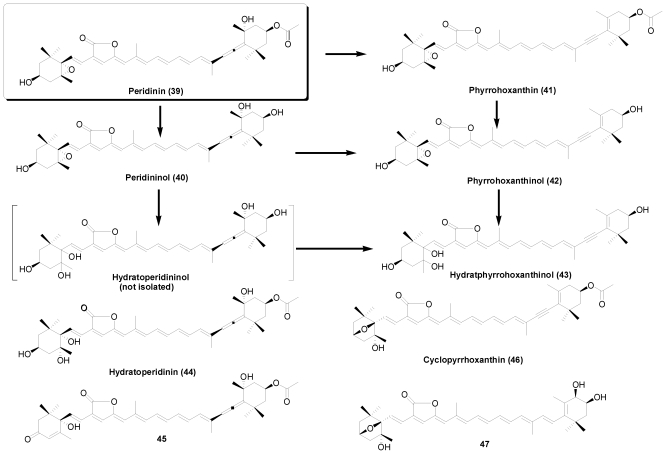

Bivalves also feed on dinoflagellates. Peridinin (39), a characteristic carotenoid in dinoflagellates with a C37-skeletal structure, and its metabolites (40-43) were also found in some bivalves. Recently, four new C37-skeletal carotenoids (44-47) were isolated from Crassostrea gigas [16,17], Paphia amabillis [20], and Corbicula japonica [24,25]. The metabolic pathways of peridinin in bivalves are shown in Figure 7. As well as fucoxanthin, the major metabolic conversions of peridinin in bivalves are hydrolysis of acetyl group, conversion of the allenic bond to an acetylenic bond, and hydrolysis cleavage of the epoxy ring, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Metabolic pathways of peridinin in bivalves.

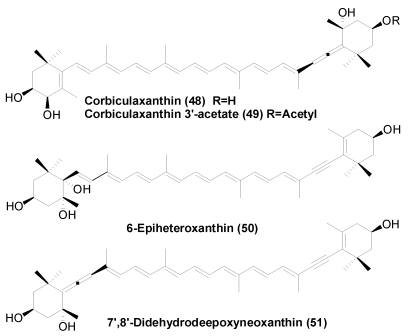

There are many reports on carotenoids in marine shellfish [6,7]. However, there are few reports on the carotenoids of shellfish inhabiting brackish or fresh water [24,25]. Four new carotenoids, corbiculaxanthin (48), corbiculaxanthin 3′-acetate (49), 6-epiheteroxanthin (50), and 7′,8′-didehydrodeepoxyneoxanthin (51), were isolated from the brackish clam Corbicula japonica and freshwater clam Corbicula sandai (Figure 8) [24,25]. 7′,8′-Didehydrodeepoxyneoxanthin (51) has an interesting structure, with both allenic and acetylenic moieties.

Figure 8.

New carotenoids in corbiculaclams.

Carotenoids found in bivalves provide a key to the food chain as well as metabolic pathways.

Astaxanthin and its esters were found to be major carotenoids in species of octopus and cuttlefish. Their astaxanthins consisted of three optical isomers and originated from dietary zooplankton [26].

5. Arthropoda (Crustaceans)

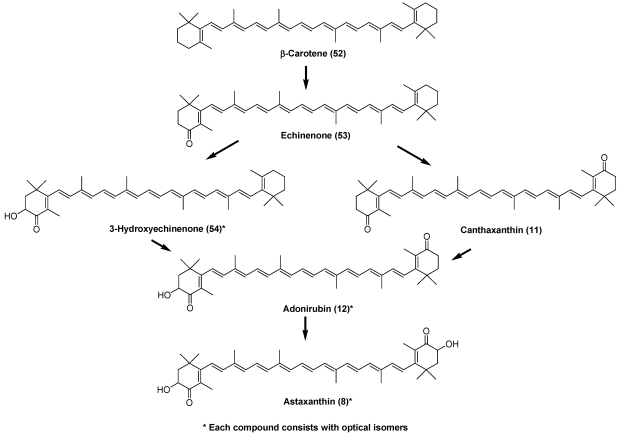

Carotenoids in the carapace of crustaceans exist as both free and esterified forms. The principal carotenoid in crustaceans is astaxanthin [6,7]. In crustaceans, astaxanthin exists as carotenoproteins such as crustacyanin, and exhibits purple, blue, and yellow colors. Many crustaceans can synthesize astaxanthin (8) from β-carotene (52), ingested from dietary algae, via echinenone (53), 3-hydroxyechinenone (54), canthaxanthin (11), and adonirubin (12), as shown in Figure 9 [6,7]. In many crustaceans, hydroxylation at C-3 (C-3′) in the 4-oxo-β-end group is none-stereo-selective. Therefore, astaxanthin, adonixanthin, and 3-hydroxyechinenone, having a 3-hydroxy-4-oxo-β-end group, present in crustaceans, are comprised of a mixture of optical isomers [6,7].

Figure 9.

Metabolism of β-carotene in crustaceans.

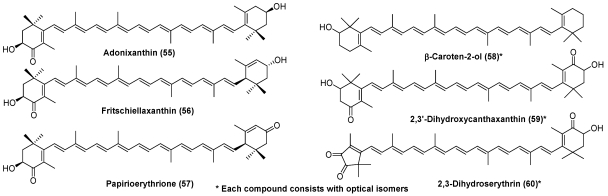

Some crustaceans can convert zeaxanthin to adonixanthin (55) and lutein to fritschiellaxanthin (56) and papyrioerythrinone (57) [1,6,7]. Crustaceans belonging to Isopoda can introduce a hydroxy group at C-2 in the β-end group. This hydroxylation is also none-stereo-selective. Therefore, β-caroten-2-ol (58) in the sea louse Ligia exotica exists as two optical isomers [1,6,7]. Recently, two new carotenoids, 2,3′-dihydroxycanthaxanthin (59) [27] and 2,3-dihydroserythrin (60) [28], were isolated from the hermit crab Paralithodes brevipes and crawfish Procambarus clarkii, respectively (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Characteristic carotenoids in crustaceans.

6. Echinodermata (Echinoderms)

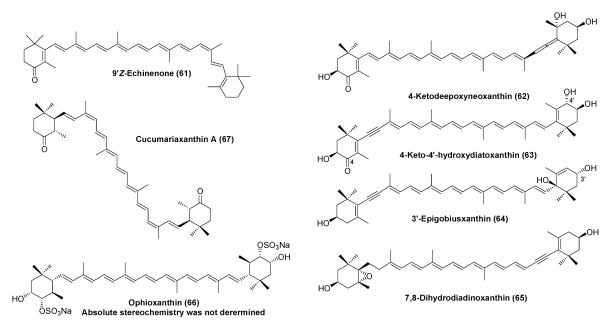

Echinenone is a well-known major carotenoid in the gonads of sea urchins and is an oxidative metabolite of β-carotene [6,7]. Echinenone from the gonads of sea urchins was found to have a 9′Z configuration (61) [29].

Starfish are carnivorous and mainly feed on bivalves and small crustaceans. Principal carotenoids in starfish are astaxanthin (8), 7,8-didehydroastaxanthin (9), and 7,8,7′,8′-didehydroastaxanthin (10). They correspond to the oxidative metabolites of β-carotene, diatoxanthin, and alloxanthin, respectively. The crown-of-thorns starfish Acanthaster planci is a large, nocturnal sea star that preys upon coral polyps. Recently, four new carotenoids: 4-ketodeepoxyneoxanthin (62), 4-keto-4′-hydroxydiatoxanthin (63), 3′-epigobiusxanthin (64), and 7,8-dihydrodiadinoxanthin (65), were isolated from A.planci as minor components along with the major carotenoids 7,8-didehydroastaxanthin, peridininol, and astaxanthin, and several other minor carotenoids including 7,8,7′,8′-tetrahydroastaxanthin, diadinoxanthin, diatoxanthin, and alloxanthin [30].

3,4,3′,4′-Tetrahydroxypirardixanthin 4,4′-disulfate, named ophioxanthin (66), was reported in the brittle star Ophioderma longicaudum [31]. Canthaxanthin and astaxanthin were found in the gonads of sea cucumbers as major components. 5,6,5′,6′-Tetrahydro-β-carotene derivatives with 9Z, 9′Z configurations, termed cucumariaxanthin (67), were isolated from the sea cucumber Cucumaria japonica [32] (Figure 11).

Recently, zeaxanthin, astaxanthin, and lutein were identified from spiny sea-star Marthasterias glacialis by HPLC-PAD-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-MS. These carotenoids showed strong cell proliferation inhibition activity against rat basophilic leukemia RBL-2H3 cancer cell line [33].

7. Protochordata (Tunicates)

As well as bivalves, tunicates are filter feeders. Carotenoids found in tunicates originate from phytoplankton such as diatoms, and are also metabolites of fucoxanthin, diatoxanthin, and alloxanthin [7,8].

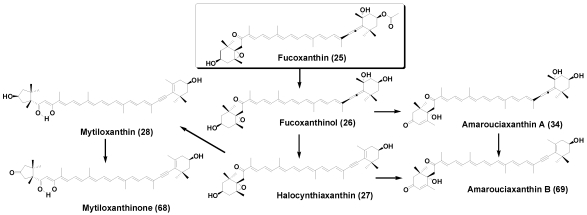

Halocynthiaxanthin (27), an acetylenic analog of fucoxanthinol (26), and mytiloxanthinone (68), an oxidative metabolite of mytiloxanthin (28), were first isolated from the sea squirt Halocynthia roretzi [34]. They are widely distributed in various tunicates. Amarouciaxanthin A (34) and amarouciaxanthin B (69), having a unique 3-oxo-6-hydroxy-ε-end group, were first isolated from the tunicate Amaroucium pliciferum [35] (Figure 12). Peridinin and its metabolites are also found in tunicates.

Figure 11.

Characteristic carotenoids in echinoderms.

Figure 12.

Metabolic pathways of fucoxanthin in tunicates.

8. Pisces (Fish)

Many fish accumulate carotenoids in their integuments and gonads. On the other hand, Salmonidae fish peculiarly accumulate astaxanthin (8) in muscle. Except for catfish, carotenoids in the integuments of fish exist in an esterified form.

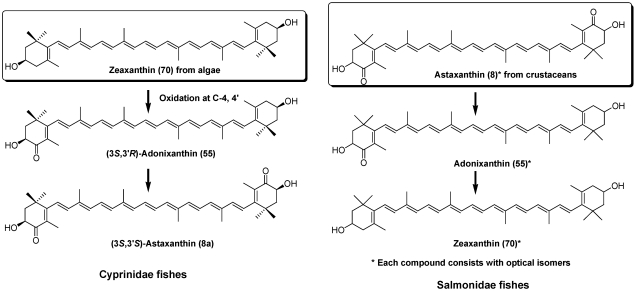

Astaxanthin (8) is widely distributed in both marine and fresh water fish. Cyprinidae fish, which inhabit fresh water, can synthesize (3S,3′S)-astaxanthin (8a) from zeaxanthin (70) by oxidative metabolic conversion (Figure 13). On the other hand, Perciformes and Salmonidae fish cannot synthesize astaxanthin from other carotenoids [6,7,36]. Therefore, astaxanthin present in these fish originates from dietary crustacean zooplankton. Astaxanthin in these marine fish comprises three optical isomers. Perciformes and Salmoidae fish can convert astaxanthin to zeaxanthin [36,37]. Therefore, zeaxanthin in these fish also exists as three optical isomers [38].

Figure 13.

Metabolism of zeaxanthin in Cyprinidae and astaxanthin in Salmonidae fish.

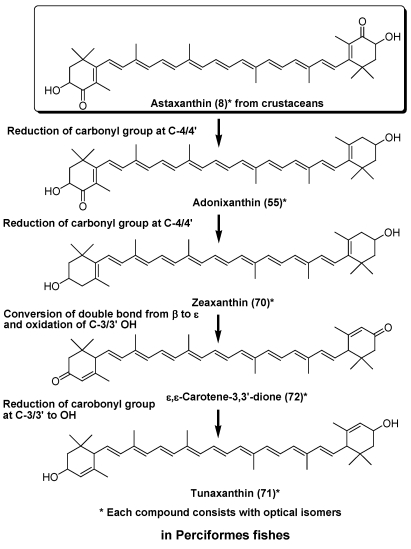

Tunaxanthin (71) is widely distributed in fish belonging to Perciformes. The bright yellow color in the fins and skin of marine fish is due to the presence of tunaxanthin. Feeding experiments involving red sea bream and yellow tail revealed that tunaxanthin (71) was metabolized from astaxanthin (8) via zeaxanthin, as shown in Figure 14 [7,36]. Carotenoids with a 3-oxo-ε-end group such as ε,ε-carotene-3,3′-dione (72) [37] are key intermediates in this metabolic conversion.

Figure 14.

Metabolism of astaxanthin in Perciformes fish.

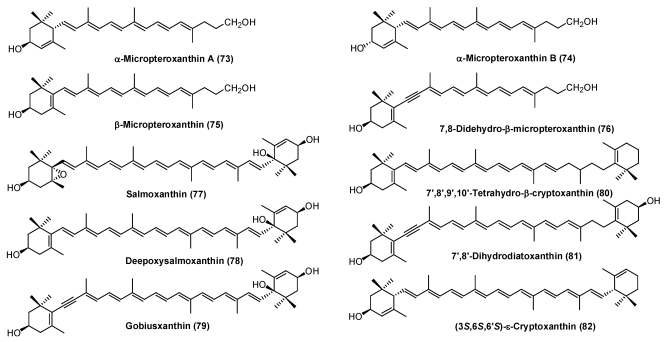

Unique apocarotenoids, micropteroxanthins (73-76), were reported from the integuments of the black bass Micropterus salmoides [39]. They were assumed to be corresponding oxidative cleavage products of tunaxanthin, lutein, and alloxanthin.

Since 2000, there are a few reports on new structures of carotenoids from fish (Figure 15). Carotenoids with a 3,6-dihydroxy-ε-end group, salmoxanthin (77), deepoxysalmoxanthin (78) (from the salmon Oncorhynchus keta) [40], and gobiusxanthin (79) (from the freshwater goby Rhinogobius brunneus) [41], were isolated. A series of carotenoids with a 7,8-dihydro- and/or 7,8,7′,8′-tetrahydro polyene chain were isolated from the integuments and eggs of the Japanese common catfish Silurus asotus [42]. Recently, new carotenoids, 7′,8′,9′,10′-tetrahydro-β-cryptoxanthin (80), 7′,8′-dihydrodiatoxanthin (81), and (3S,6S,6′S)-ε-cryptoxanthin (82), were isolated from the integuments and gonads of the Japanese common catfish as minor carotenoids [43].

Figure 15.

New carotenoids from fish.

9. Mammalia (Mammals)

There are few reports available on carotenoids in marine mammals. Only, β-carotene and lutein were reported from the dolphin [44]. The whale is the biggest marine mammal. Whales feed on krill, which is an important dietary source of astaxanthin for marine animals. Therefore, whales might accumulate astaxanthin in the body.

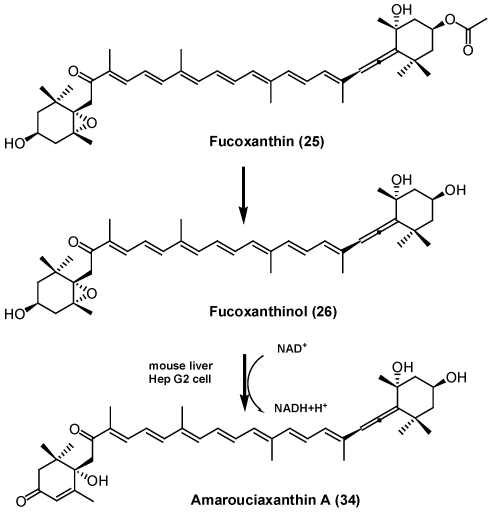

Recently, absorption and metabolism of fucoxanthin (25) in mice was investigated. Dietary administrated fucoxanthin was converted to amarouciaxanthin A (34) via fucoxanthinol (26) in mice [45,46] (Figure 16). This metabolic conversion was also observed in human hepatoma cell HepG2 and required NAD(P)+ as a cofactor [45].

Figure 16.

Metabolism of fucoxanthin in mice.

10. Role of Carotenoids in Marine Animals and Utilization of Carotenoids for Aquaculture

Carotenoids are not essential in the nutritional sense. However, they are beneficial for animal health. It is well-known that carotenoids have an unsubstituted β-end group, such as β-carotene, α-carotene, and the β-cryptoxanthin precursor of vitamin A in animals. Furthermore, canthaxanthin was also converted to retinol in Salmoidae fish. 3-Hydroxy carotenoids: lutein, zeaxanthin, and astaxanthin, were also reported to be precursors of 3,4-dehydroretinol (Vitamin A2) in some freshwater fish [36,47].

Many marine animals accumulate carotenoids in their integuments. Integumentary carotenoids may contribute to photoprotection, camouflage, and signaling such as breeding color.

Carotenoids have excellent antioxidative activities for quenching singlet oxygen and inhibiting lipid peroxidation. Astaxanthin supplementation in Salmonidae fish suppressed oxidative stress [48,49].

Marine animals also accumulate carotenoids in their gonads. Carotenoids are assumed to be essential for reproduction in marine animals. Astaxanthin supplementation in cultured salmon and red sea bream increased ovary development, fertilization, hatching, and larval growth [50]. In the case of the sea urchin, supplementation with β-carotene, which was metabolized to echinenone, also increased reproduction and the survival of larvae [51]. Carotenoids also enhance immune activity in marine animals [52,53].

Carotenoids are used for pigmentation in several aquaculture fish. Synthetic and natural astaxanthin from Phaffia yeast and Haematococcus algae is widely used for the pigmentation of salmon, trout, and red sea bream. Lutein from marigold is also used as a yellow coloration for cultured marine fish such as yellow tail and red sea bream. Zeaxanthin from spirulina is used as a red coloration for goldfish and ornamental carp.

11. Conclusions

In the present review, I have described marine animal carotenoids from natural product chemistry, metabolism, food chain, and chemosystematic viewpoints and also describe new structural carotenoids isolated from marine animals during the last decade.

In plants and photosynthetic bacteria, biosynthetic roots of carotenoids were identified at the enzymatic and gene level. On the other hand, neither enzymes nor genes for the metabolism of carotenoids in animals have been clarified. Therefore, chemical, biochemical, and analytical approaches are still important to clarify carotenoids in animals.

Interesting new structural carotenoids can still be found in marine animals. The structures of these new carotenoids provide information on the function and food chain, as well as metabolic pathways in marine animals.

References

- 1.Britton G., Liaaen-Jensen S., Pfander H. Carotenoids Hand Book. Birkhäuser; Basel, Switzerland: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maoka T., Akimoto N. Natural product chemistry in carotenoid, some experimental techniques for structural elucidation and analysis of natural carotenoids. Carotenoid Sci. 2008;13:10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maoka T. Recent progress in structural studies of carotenoids in animals and plants. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009;483:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maoka T. Structural studies of natural carotenoids by our research group during the three decade. Carotenoid Sci. 2009;14:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaaen-Jensen S. Marine carotenoids—Selected topics. New J. Chem. 1990;14:747–759. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liaaen-Jensen S. Carotenoids in Food Chain. In: Britton G., Liaaen-Jensen S., Pfander H., editors. Carotenoids: Biosynthesis and Metabolism. Vol. 3. Birkhäuser; Basel, Switzerland: 1998. pp. 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuno T. Aquatic animal carotenoids. Fish. Sci. 2001;67:771–789. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuno T. Animal carotenoids. In: Krinsky N.I., Mathews-Roth M.M., Taylor R.F., editors. Carotenoids Chemistry and Biology. Plenum Press; New York, NY, USA: 1989. pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuno T., Hirao S. Marine carotenoids. In: Ackman R.G., editor. Marine Biogenic Lipids, Fats, and Oils. Vol. 1. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 1989. pp. 251–388. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers E.W., Molinski T.F. A cytotoxic carotenoid from the marine spongePrianos osiro. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:450–452. doi: 10.1021/np0497797. The IUPAC name (3R,3′R,5S)-3,3′,5,19′-tetrahydroxy-7′,8′-didehydro-γ,ε-carotene-8-one was given for compound5in this literature. However, this IUPAC name is un-correct. Correct IUPAC name for5is (3R,3′R,5S)-3,3′,5,19′-tetrahydroxy-7′,8′-didehydro-5,8-dihydro-γ,ε-caroten-8-one. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maoka T., Akimoto N., Tsushima M., Komemushi S., Harada R., Sameshima N., Iwase F., Sakagami Y. Carotenoids in corals and sea snails. Carotenoid Sci. 2010 submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsushima M., Maoka T., Matsuno T. Comparative biochemical studies of carotenoids in marine invertebrates. The first positive identification of ε,ε-carotene derivatives and isolation of two new carotenoids from chitons. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1989;93B:665–671. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsushima M., Maoka T., Matsuno T. Structure of carotenoids with 5,6-dihydro-β-end group from the spindle shell Fusinus perplexus. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1139–1142. doi: 10.1021/np010060y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamashita E., Matsuno T. A new apocarotenoid from the sea hareAplysia kurodai. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1990;96B:465–470. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maoka T. A new apocarotenoid from marine shellfish. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:616–617. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maoka T., Hashimoto K., Akimoto N., Fujiwara Y. Structures of five new carotenoids from the oyster Crassostrea gigas. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:578–581. doi: 10.1021/np000476w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maoka T., Fujiwara Y., Hashimoto K., Akimoto N. Structures of new carotenoids with a 3,4-dihydroxy-β-end group from the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:1207–1209. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maoka T., Fujiwara Y., Hashimoto K., Akimoto N. Characterizatoin of fucoxanthin and fucoxanthinol esters in the chinese surf clam, Mactra chinensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:1563–1567. doi: 10.1021/jf063139n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maoka T., Akimoto N., Murakoshi M., Sugiyama K., Nishino H. Carotenoids in clams, Ruditapes philippinarum and Meretrix petechialis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:5784–5788. doi: 10.1021/jf1006243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maoka T., Akimoto N., Yim M.-J., Hosokawa M., Miyashita K. A new C37-skeletal carotenoid from the clam, Paphia amabillis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:12069–12072. doi: 10.1021/jf802717b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiwara Y., Maoka T., Ookubo M., Matsuno T. Crassostreaxanthins A and B: novel marine carotenoids from the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:4941–4944. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tode C., Yamano Y., Ito M. First total synthesis of crassostreaxanthin B. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1999;1:1625–1626. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tode C., Yamano Y., Ito M. Carotenoids and related polyenes. Part 7. Total synthesis of crassostreaxanthin B Applying the stereoselective rearrangement of tetrasubstituted epoxides. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2001;1:3338–3345. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maoka T., Fujiwara Y., Hashimoto K., Akimoto N. Carotenoids in three species of corbicula clams,Corbicula japonica,Corbicula sandai,andCorbicula sp.(Chinese freshwater corbicula clam) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:8357–8364. doi: 10.1021/jf058088t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maoka T., Fujiwara Y., Hashimoto K., Akimoto N. Structure of new carotenoids from the corbicula clam Corbicula japonic. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:1341–1344. doi: 10.1021/np058053n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maoka T., Yokoi S., Matsuno T. Comparative biochemical stidies of carotenoids in nine species of Cephalopoda. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1989;92B:247–250. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maoka T., Akimoto N. 2,3′-Dihydroxycanthaxanthin, a new carotenoid with a 2-hydroxy-4-oxo-β-end group from the hermit Crab, Paralithodes brevipes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2006;54:1462–1464. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maoka T., Ando S. Isolation of purple nor-carotenoid, 2,3-dihydroserythrin, from crawfish Procambarus clarkii. Fish. Sci. 2007;73:967–968. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsushima M., Matsuno T. Occurrence of 9′Z-β-echinenone of the sea urchinPseudocentrotus depressus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1997;118B:921–925. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maoka T., Akimoto N., Terada Y., Komemushi S., Harada R., Sameshima N., Sakagami Y. Structure of minor carotenoids from crown-of-thorns starfish, Acanthaster planci. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:675–678. doi: 10.1021/np100021u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’auria M.V., Riccio R., Minale L. Ophioxanthin, a new marine carotenoid sulphate from the ophiuroid Ophioderma longicaudum. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:1871–1872. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsushima M., Fujiwara Y., Matsuno T. Novel marine di-Z-carotenoids, cucumariaxanthins A, B and C from the sea cucumber Cucumaria japonica. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:30–34. doi: 10.1021/np960022s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreres F., Pereira D.M., Gil-Izquierdo A., Valentão P., Botelho J., Mouga T., Andrade P.B. HPLC-PAD-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-MS metabolite profiling of cytotoxic carotenoids from the echinoderm Marthasterias glacialis(spiny sea-star) J. Sep. Sci. 2010;33:2250–2257. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuno T., Ookubo M., Nishizawa T., Shimizu I. Carotenoids of sea suirts.I. New marine carotenids, halocynthiaxanthin and mytiloxanthinone fromHalocynthia roretzi. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1984;32:4309–4315. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuno T., Ookubo M., Komori T. Carotenoids of tunicates. III: The structural elucidation of two new marine carotenoids, amarouciaxanthin A and B. J. Nat. Prod. 1985;48:606–613. doi: 10.1021/np50040a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiedt K. Absorption and metabolism of carotenoids in birds, fish and crustaceans. In: Britton G., Liaaen-Jensen S., Pfander H., editors. CarotenoidsBiosynthesis and Metabolism. Birkhäuser; Basel, Switzerland: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuno T., Katsuyama M., Maoka T., Hirono T., Komori T. Reductive metabolic pathways of carotenoids in fish (3S,3′S)-astaxanthin to tunaxanthin A, B and C. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1985;80B:779–789. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maoka T., Arai A., Shimizu M., Matsuno T. The first isolation of enantiomeric andmeso-zeaxanthin in nature. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1986;83B:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(86)90341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashita E., Arai S., Matsuno T. Metabolism of xanthophylls to vitamin A and new apocarotenoids in liver and skin of black bass,Micropterus salmoides. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1996;113B:485–489. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsuno T., Tsushima M., Maoka T. Salmoxanthin, deepoxy-salmoxanthin and 7,8-didehydrodeepoxy-salmoxanthin from the salmon Oncorhynchus keta. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:507–510. doi: 10.1021/np0004294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsushima M., Mune E., Maoka T., Matsuno T. Isolation of stereoisomeric epoxy carotenoids and new acetylenic carotenoid from the common freshwater goby Rhinogobius brunneus. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:960–964. doi: 10.1021/np990580h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsushima M., Ikuno Y., Nagata S., Kodama K., Matsuno T. Comparative biochemical studies of carotenoids in catfishes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 2002;133B:331–336. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(02)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maoka T., Akiomoto N. Structures of minor carotenoids from the Japanese common catfish, Silurus asotus. Chem. Phram. Bull. 2011;59:140–145. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slifka K.A., Bowen P.E., Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis M. A survey of serum and dietary carotenoids in captive wild animals. J. Nutr. 1999;129:380–390. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asai A., Sugawara H., Ono H., Nagao A. Biotransformation of fucoxanthinol into amarouciaxanthin A in mice and HepG2 cells: formation and cytotoxicity of fucoxanthin metabolites. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:205–211. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto T., Ozaki Y., Taminato M., Das S.K., Mizuno M., Yoshimura K., Maoka T., Kanazawa K. The distribution and accumulation of fucoxanthin and its metabolites after oral administration in mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2009;102:242–248. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508199007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matsuno T. Xanthophylls as precursor of retinoids. Pure Appl. Chem. 1991;63:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakano T., Tosa M., Takeuchi M. Improvement of biochemical features in fish health by red yeast and synthetic astaxanthin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995;43:1570–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakano T., Kanmuri T., Sato M., Takeuchi M. Effect of astaxanthin rich red yeast (Phaffia rhodozyma) on oxidative stress in rainbow trout. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1426:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Torrissen O.J., Christiansen R. Requirements for carotenoids in fish diets . J. Appl. Ichthyol. 1995;11:225–230. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsushima M., Kawakami T., Mine M., Matsuno T. The role of carotenoids in the development of the sea urchin Pseudocentrotus depressus. Invert. Reprod. Develop. 1997;32:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson I., Choubert G.D., Houlihan F., Secombes C.J. The effect of dietary Vitamin A and Astaxanthin on the immunocompetence of rainbow trout. Aquaculture. 1995;133:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawakami T., Tsushima M., Katabami Y., Mine M., Ishida A., Matsuno T. Effect of β,β-carotene, β-echinenone, astaxanthin, fucoxanthin, vitamin A and vitamin E on the biological defense of the sea urchin Pseudocentrotus depressus. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1998;226:165–174. [Google Scholar]