Abstract

RNA silencing mediated by siRNAs plays an important role as an anti-viral defense mechanism in plants and other eukaryotic organisms, which is usually counteracted by viral RNA silencing suppressors (RSSs). The ipomovirus Cucumber vein yellowing virus (CVYV) lacks the typical RSS of members of the family Potyviridae, HCPro, which is replaced by an unrelated RSS, P1b. CVYV P1b resembles potyviral HCPro in forming complexes with synthetic siRNAs in vitro. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays showed that P1b, like potyviral HCPro, interacts with double-stranded siRNAs, but is not able to bind single-stranded small RNAs or small DNAs. These assays also showed a preference of CVYV P1b for binding to 21-nt siRNAs, a feature also reported for HCPro. However, these two potyvirid RSSs differ in their requirements of 2-nucleotide (nt) 3′ overhangs and 5′ terminal phosphoryl groups for siRNA binding. Copurification assays confirmed in vivo P1b–siRNA interactions. We have demonstrated by deep sequencing of small RNA populations interacting in vivo with CVYV P1b that the size preference of P1b for small RNAs of 21 nt also takes place in the plant, and that expression of this RSS causes drastic changes in the endogenous small RNA populations. In addition, a site-directed mutagenesis analysis strongly supported the assumption that P1b–siRNA binding is decisive for the anti-silencing activity of P1b and localized a basic domain involved in the siRNA-binding activity of this protein.

Keywords: RNA silencing suppressors, short interfering RNAs, RNA binding, siRNA sequestering

INTRODUCTION

Plant viruses overcome various defensive barriers, including RNA silencing when they infect plants (Covey et al. 1997; Ratcliff et al. 1997; Dangl and Jones 2001; Voinnet 2001; Soosaar et al. 2005; Jones and Dangl 2006; Ding and Voinnet 2007; Csorba et al. 2009). RNA silencing suppressor proteins (RNA silencing suppressors [RSSs]) are key components of the counterdefense system allowing viruses to overcome these barriers (Roth et al. 2004; Diaz-Pendon and Ding 2008; Valli et al. 2009).

RSS-defective mutant viruses are usually either noninfectious, markedly debilitated (Deleris et al. 2006; Garcia-Ruiz et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010), or their effects are transient so that the infected plants eventually recover (Ratcliff et al. 1997; Qu and Morris 2002; Havelda et al. 2003). A challenging inference from the analysis of RSSs is that components of the RNA silencing machinery could influence the host range of the virus and, consistent with this idea, an RSS from a virulent virus may mediate the systemic infection by a second virus that is normally restricted to the site of inoculation (Sáenz et al. 2002).

The cysteine proteinase HCPro encoded by members of the genus Potyvirus of the family Potyviridae was one of the first described viral suppressors of silencing (Anandalakshmi et al. 1998; Brigneti et al. 1998; Kasschau and Carrington 1998). However, the sequence encoding this protein is absent from the genome of some members of the Ipomovirus genus, such as Cucumber vein yellowing virus (CVYV), Squash vein yellowing virus (SqVYV), and Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) (Janssen et al. 2005; Li et al. 2008; Mbanzibwa et al. 2009). Whereas in typical potyviruses the 5′ terminal region of the genome codes for a single serine proteinase (P1), the 5′ terminal region of the genome of CVYV and SqVYV codes for two similar serine proteinases arranged in tandem (P1a and P1b), and the P1b has been shown to have RNA silencing suppression activity (Valli et al. 2006; Li et al. 2008). These P1b proteins, together with homologs in the Ipomovirus, Brambyvirus, and Poacevirus (or Susmovirus) genera form a group of P1 proteins that is phylogenetically and functionally distinct from the potyviral P1s, and the P1a proteins of CVYV and SqVYV (Valli et al. 2007; Susaimuthu et al. 2008; Fellers et al. 2009; Tatineni et al. 2009).

The CVYV P1b is able to bind in vitro siRNAs—key elements of the RNA silencing machinery—and it seemed likely that siRNA sequestration plays a major role in the suppression activity of this protein (Valli et al. 2008), as has been demonstrated or suggested for other RSSs (Vargason et al. 2003; Lakatos et al. 2006). In the present study, consistent with that prediction, we show that CVYV P1b binds small RNAs in vivo and that this property is strictly correlated with its silencing suppression activity. In addition, our data show specific features of the small RNA molecules relevant for CVYV P1b recognition, which only partially matches those contributing to potyviral HCPro binding, and map a CVYV P1b siRNA-binding domain.

RESULTS

P1b binds preferentially double-strand siRNAs of 21 nucleotides

The P1b protein of CVYV is a RSS that resembles the typical potyviral RSS HCPro in its ability to interact with synthetic siRNA molecules in vitro (Valli et al. 2008). To further characterize this siRNA binding activity of CVYV P1b, a NTAP (N-terminal Tandem Affinity Purification)-tagged P1b was expressed by agroinfiltration in Nicotiana benthamiana plants, partially purified by affinity chromatography, and then probed with various single-stranded (ss-) or double-stranded (ds-) forms of 32P-labeled siRNAs in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

As expected, NTAP–P1b caused a shift in the electrophoretic mobility of 21-nt ds-siRNA. In contrast, NTAP–P1b did not affect the mobility of 21-nt ss-siRNA (Fig. 1A) or of ss- or ds-21-nt DNA (Fig. 1B). These data show that P1b is a nucleic acid binding protein with strong preferences for ds-RNA.

FIGURE 1.

P1b binds specifically double-stranded small RNAs. (A) Increasing amounts of NTAP–P1b purified by affinity chromatography (30, 60, 120, 240, and 480 nM), as well as bovine serum albumin (BSA; 250 nM) or just buffer (-), were incubated with the indicated 32P-labeled small RNAs. (B) Increasing amounts of NTAP–P1b purified by affinity chromatography (100 and 300 nM), as well as BSA (500 nM) or just buffer (-), were incubated with the indicated 32P-labeled nucleic acids. Double-stranded molecules had 2-nt 3′ protruding ends. Complexes were resolved in polyacrylamide gels and revealed by autoradiography. Upper and lower arrows indicate bound and free 32P-labeled probes, respectively. The asterisk indicates the presence of nonspecific shift.

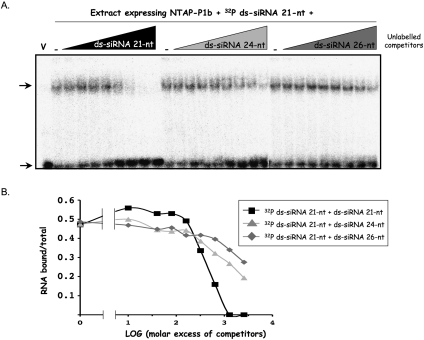

To determine whether P1b can discriminate between RNAs of different sizes, we used a fixed amount of 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs in the same assay, but with increasing amounts of 21-, 24-, or 26-nt unlabeled ds-siRNAs (Fig. 2A). Although 24-nt and, to a lesser extent, 26-nt ds-siRNAs were able to compete the binding of the 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs to NTAP–P1b, they prevented the binding of the radioactive probe much less efficiently than the 21-nt ds-siRNA competitor, and they were unable to produce a complete competition even with a very large molar excess (Fig. 2B). This result suggests that P1b binds preferentially to the ds-siRNAs of the 21 nt that correspond to the main siRNA species produced from plant RNA viruses by silencing.

FIGURE 2.

P1b binds ds-siRNAs with size selectivity. (A) Crude protein extracts from N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with agrobacteria carrying p35S–NTAP–P1b or the empty pBIN19 vector (lane V), and harvested at 6 dpi, were incubated with 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs in the presence of the indicated unlabeled ds-siRNA competitors added in increasing molar excess (10-, 40-, 80-, 160-, 320-, 640-, 1280-, and 2560-fold) or in the absence of them (lanes V and -). Complexes were resolved in polyacrylamide gels and revealed by autoradiography. Upper and lower arrows indicate bound and free 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs, respectively. (B) Densitometric analysis of the autoradiographic signals. The ratio bound RNA/total RNA of each lane was plotted as a function of logarithm of molar excess of competitors. All ds-siRNAs had 2-nt 3′ protruding ends.

P1b and HCPro show different structural requirements for siRNA binding

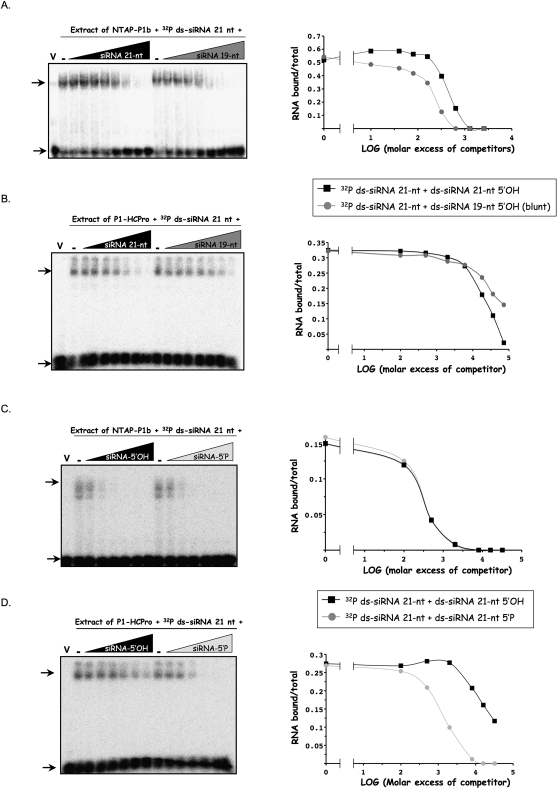

Natural siRNAs have a 5′ terminal phosphoryl group and a 2-nt overhang with a free OH at the 3′ end produced by the Dicer-like enzyme. HCPro, the main RSS from potyviruses, shows a higher affinity for 21-nt ds-siRNAs carrying the 3′ overhang than for the equivalent 19-nt blunt-ended ds-siRNA (Lakatos et al. 2006; Mérai et al. 2006). To assess whether CVYV P1b binds the same structures, we used NTAP–P1b or the HCPro of the potyvirus Plum pox virus (PPV) in EMSA competition assays. Protein extracts of agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaves expressing the RSSs were incubated with 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs with 3′ overhangs and increasing amounts of unlabeled 21-nt siRNAs with 3′ overhangs or 19-nt blunt ended siRNAs.

NTAP–P1b showed a slight preference for 19-nt ds-siRNAs (Fig. 3A) whereas PPV HCPro interacted preferentially with 21-nt ds-siRNAs (Fig. 3B). Intriguingly, the excess of unlabeled competitors required to displace the 32P-labeled siRNA was much higher for HCPro than for NTAP–P1b (Fig. 3A,B). NTAP–P1b bound 5′-P and 5′-OH siRNAs with similar affinity (Fig. 3C), whereas PPV HCPro showed a preference for siRNA carrying the 5′-P group (Fig. 3D), a fact that is in agreement with the observed differences in the competition efficiency of unlabeled 5′-OH ds-siRNAs (Fig. 3A,B). The nucleic acid binding mechanism of CVYV NTAP–P1b is therefore likely to differ from potyviral HCPro and the well studied RSSs tombusviral P19 that also has a preference for a 5′ terminal P (Fig. 3D; Vargason et al. 2003).

FIGURE 3.

P1b and HCPro display different structural requirements for efficient siRNA recognition. Crude protein extracts from N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with agrobacteria carrying p35S–NTAP–P1b (A,C), p35S-P1HC (B,D), or the empty pBIN19 vector (lanes V), and harvested at 6 dpi, were incubated with 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs in the absence (lanes V and -) or in the presence of increasing molar excesses (A, 10-, 40-, 80-, 160-, 320-, 640-, 1280- and 2560-fold; B, 100-, 500-, 2000-, 8000-, 16,000-, 36,000-, and 72,000-fold; C,D, 100-, 500-, 2000-, 8000-, 16,000- and 32,000-fold) of unlabeled competitors: nonphosphorylated 21-nt ds-siRNAs with 2-nt 3′ protruding ends (black triangles, A–D); nonphosphorylated blunt-ended 19-nt ds-siRNAs (dark gray triangles, A,B); phosphorylated 21-nt ds-siRNAs with 2-nt 3′ protruding ends (light gray triangles, C,D). Complexes were resolved in polyacrylamide gels and revealed by autoradiography (left panels). Upper and lower arrows indicate bound and free 32P-labeled ds-siRNAs, respectively. For all the competition experiments, densitometric analyses of the autoradiographic signals are shown in the right panels. The ratio bound RNA/total RNA of each lane was plotted as a function of logarithm of molar excess of competitors.

P1b binds siRNA in vivo

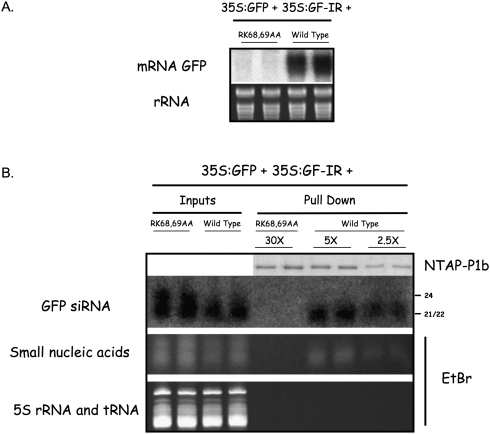

To determine whether CVYV P1b binds siRNAs in vivo, we partially purified NTAP–P1b by affinity from N. benthamiana leaves in which three constructs were transiently expressed: p35S:GFP (expressing GFP mRNA as reporter), the strong silencing inducer p35S:GF-IR (expressing an inverted repeat that generates a partial GFP dsRNA) and the expression construct of wild-type NTAP–P1b or its RK68,69AA inactive mutant (Valli et al. 2008).

Northern blot analysis showed that the co-infiltration with wild type but not with the mutant form of p35S–NTAP–P1b prevented GFP mRNA silencing, whereas the levels of GFP-specific siRNAs were similar (Fig. 4A,B). However, GFP-derived siRNAs were bound to NTAP–P1b but not to the mutant (Fig. 4B), which were detected even when lesser amounts of the wild-type protein were used as siRNA source (2.5X lanes, Fig. 4B). The total small nucleic acids detected by ethidium bromide staining also bound preferentially to wild-type NTAP–P1b, but not the mutant (Fig. 4B, lower panel). These results show that CVYV P1b interacts specifically with siRNAs in planta.

FIGURE 4.

P1b binds siRNAs in vivo. N. benthamiana plants were co-infiltrated with agrobacteria carrying p35S:GFP and p35S:GF-IR plus p35S–NTAP–P1b or p35S–NTAP–P1b RK68,69AA. The infiltrated leaves were harvested at 6 dpi. (A) Northern blot analysis of GFP mRNA extracted from infiltrated leaves. Agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide is shown as loading control (rRNA). (B) Small RNAs separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide (Small nucleic acids) and GFP-specific siRNAs detected by Northern blot analysis (GFP siRNAs) from either infiltrated leaves (Inputs) or NTAP–P1b, wild-type or RK68,69AA mutant, purified by affinity chromatography (Pull down). Numbers above each line (30X, 5X, 2.5X) indicate the times of enrichment relative to Inputs. Bands corresponding to 21 nt/22 nt, and 24 nt, are indicated. 5S rRNA and tRNA stained with ethidium bromide are shown as a loading control. The samples of purified NTAP–P1b proteins used for the siRNA extraction were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to assess their protein amounts (NTAP–P1b).

P1b induces drastic changes in N. benthamiana small RNA populations

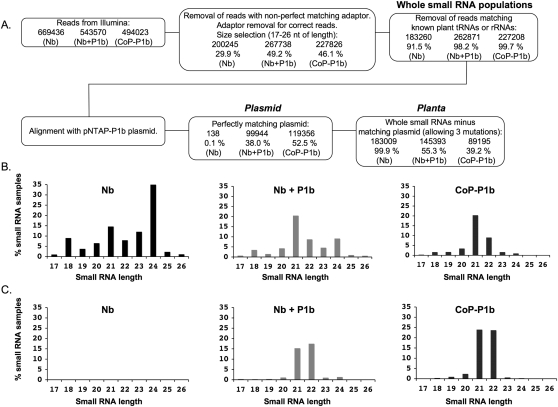

To establish whether CVYV P1b affects the endogenous populations of small RNAs we used Illumina sequence analysis of small RNAs in unfractionated extracts of untreated N. benthamiana leaves (Nb) or of leaves in which NTAP–P1b was transiently expressed (Nb + P1b) (Fig. 5A). We also sequenced the siRNAs bound to NTAP–P1b (CoP–P1b) in these leaves (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Enrichment in 21-nt small RNAs associated to NTAP–P1b expression. (A) Flowchart followed for the analysis of small RNA sequences obtained by deep sequencing of small RNAs from N. benthamiana (Nb), N. benthamiana infiltrated with agrobacteria carrying p35S–NTAP–P1b (Nb + P1b), or a fraction of NTAP–P1b purified by affinity chromatography from these plants (CoP–P1b). The number of reads passing each step and the percentage with respect to the previous step are shown for each sample. (B) Size-distribution histograms of endogenous (planta) small RNAs of each sample, expressed as percentage with respect to the planta small RNA population. (C) Size-distribution histograms of plasmid-derived (plasmid) small RNAs of each sample, expressed as percentage with respect to the plasmid small RNA population.

The small RNAs from N. benthamiana leaves were predominantly 24 nt (Fig. 5B, left panel) unless NTAP–P1b was expressed when 21-nt species were most abundant (Fig. 5B, middle panel). These changes on size profile were not observed when an empty binary vector was agroinfiltrated (Supplemental Fig. S1). Correspondingly, the NTAP–P1b protein co-purified with small RNAs that were predominantly 21 nt in length (Fig. 5B, right panel). A high amount of small RNAs of samples Nb + P1b and CoP–P1b matched the p35S–NTAP–P1b sequence (Fig. 5A), mainly in the T-DNA sequence (Supplemental Fig. S2). A large majority of these small RNAs were of 21 and 22 nt, being 21-nt molecules slightly overrepresented in the siRNA population copurified with NTAP–P1b (Fig. 5C).

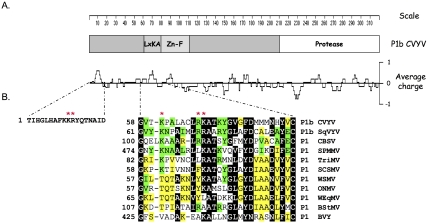

A basic conserved domain is involved in small RNA binding

A basic domain characterized by an LxKA signature, which is partially conserved in P1 proteins from ipomoviruses and tritimoviruses (Fig. 6), could be involved in siRNA binding (Valli et al. 2008). To test this hypothesis we introduced point mutations in p35S–NTAP–P1b affecting basic amino acids not only in this motif but also in amino acids of a nonconserved basic region present at the N-terminus of the CVYV P1b (Fig. 6); and the silencing suppression and siRNA-binding activities of the mutant proteins were assayed. The mutant KR10,11AA of the nonconserved domain showed a silencing suppressing activity indistinguishable from that of wild-type NTAP–P1b. In addition, the siRNA binding activity of NTAP–P1b KR10,11AA was comparable to that of wild-type protein in an EMSA in vitro assay (Supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 6.

Basic domains in P1b-like proteins. (A) Schematic representation of CVYV P1b showing the location of conserved domains and a plot of charge density along the protein. (B) Details of two basic domains placed at the N-terminal half of CVYV P1b. An amino acid alignment of the second domain, which is partially conserved in P1b-like proteins, is shown. Proteins included in the alignment are as follows: P1b from the ipomoviruses CVYV and Squash vein yellowing virus (SqVYV), and P1 from the ipomoviruses Cassava brown streak virus (CBSV) and Sweet potato mild mottle virus (SPMMV), from the tritimoviruses Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV), Oat necrotic mottle virus (ONMV), Wheat eqlid mosaic virus (WEqMV) and Brome streak mosaic virus (BStMV), and from the still unclassified potyvirid Triticum mosaic virus (TriMV), Sugarcane streak mosaic virus (SCSMV), and Blackberry virus Y (BVY). Boxed amino acids are identical or chemically similar between at least two ipomoviruses (green boxes), between at least three nonipomoviruses (yellow boxes), or between at least two ipomoviruses plus two nonipomovirus (black boxes). Dashes represent gaps. The position of the first amino acid of each aligned segment is indicated on the left side of the sequence. The asterisks indicate the residues of CVYV P1b that were mutated in this work.

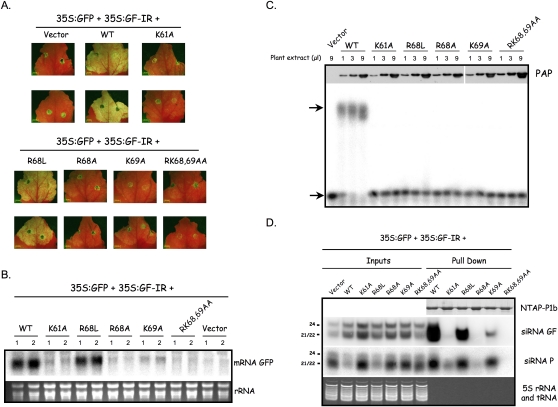

In the R68A, K69A, and K61A mutants, a basic amino acid of the LxKA domain was replaced with alanine, whereas in R68L an orthologous residue of Sweet potato mild mottle virus (SPMMV) P1 was substituted into the CVYV protein (Fig. 6). We also assayed the RK68,69AA double mutant that had been tested previously (Valli et al. 2008). The control for this assay involved transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves of p35S:GFP and p35S:GF-IR plus an empty vector, which displayed no green fluorescence (Fig. 7A) and very low accumulation of GFP mRNA due to RNA silencing (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the inclusion of p35S:GFP, p35S:GF-IR, and wild-type p35S–NTAP–P1b resulted in strong green fluorescence (Fig. 7A) and high levels of GFP mRNA (Fig. 7B) because silencing was suppressed. Mutations K61A, R68A, K69A, and RK68,68AA drastically disturbed the silencing suppression activity of NTAP–P1b as assayed by GFP fluorescence (Fig. 7A) or GFP mRNA (Fig. 7B). However the R68L mutant exhibited only weak loss of silencing suppression activity as assayed by both green fluorescence (Fig. 7A) and GFP mRNA accumulation levels (Fig. 7B). It is likely that the RSS phenotypes in K61A, R68A, K69A, and RK68,68AA mutants is associated with loss of siRNA binding because the NTAP–P1b nonfunctional mutant proteins showed no binding to siRNAs in an EMSA (Fig. 7C). They also showed reduced siRNA binding in an in vivo co-purification assay (Fig. 7D), in which bound GFP-specific siRNA was detected by Northern blot analysis. These GFP-specific siRNAs corresponded to the inverted repeat trigger of GFP silencing (siRNA GF panel, Fig. 7D) and the secondary siRNAs derived from the 3′ end of the reporter mRNA (siRNA P panel, Fig. 7D). Whereas no co-precipitation of siRNAs with NTAP–P1b RK68,69AA could be detected, the K61A, R68A, K69A mutant proteins pulled GFP siRNAs down, although with lower efficiencies than the wild-type (Fig. 7D, Pull down). NTAP–P1b K69A, which slightly protected GFP mRNA from degradation (Fig. 7B), was more effective in siRNA pull down than the K61A and R68A versions, which appear to be as inactive as RK68,69AA in suppressing the RNA silencing (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Silencing suppression activity and siRNA binding capacity of P1b mutant proteins. N. benthamiana plants were co-infiltrated with agrobacteria carrying p35S:GFP and p35S:GF-IR plus empty pBIN19 plasmid (Vector), wild-type p35S–NTAP–P1b or derivatives of this plasmid with the indicated mutations. The infiltrated leaves were harvested at 4 dpi. (A) GFP fluorescence pictures taken under a fluorescence stereomicroscope. (B) Northern blot analysis of GFP mRNA extracted from infiltrated leaves. Agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide is shown as loading control (rRNA). (C) siRNA binding analysis by EMSA. Crude protein extracts of infiltrated leaves (three doses: 1, 3, and 9 μL) were incubated with 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs. Complexes were resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and revealed by autoradiography. The amount of NTAP–P1b proteins present in each extract was estimated by Western blot analysis with Peroxidase anti-Peroxidase complex (on top of the panel). Upper and lower arrows indicate bound and free 32P-labeled 21-nt ds-siRNAs, respectively. (D) Northern blot analysis of both GF- and P-derived siRNAs from either co-infiltrated leaves (Inputs) or NTAP–P1b proteins purified by affinity chromatography (Pull down). Pull down samples are enriched 20X (WT), 30X (K61A), 30X (R68L), 50X (R68A), 35X (K69A), and 50X (RK68,69AA) relative to the Inputs. Bands corresponding to 21 nt/22 nt, and 24 nt, are indicated. 5S rRNA and tRNA stained with ethidium bromide are shown as loading control. The samples of purified NTAP–P1b proteins used for the siRNA extraction were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to assess their protein amounts (NTAP–P1b).

The siRNA binding of the R68L mutant was completely absent in the EMSA assay (Fig. 7C). However, in agreement with the quite strong silencing suppression activity of this mutant (Fig. 7A,B), in the in vivo co-purification assay, NTAP–P1b R68L bound large amounts of both primary and secondary siRNAs, although still less than the wild-type protein (Fig. 7D).

It is important to remark that whereas GFP siRNAs of 21–24 nt accumulated in the agroinfiltrated plants (Fig. 7D, Input), a single hybridization band, corresponding to species of 21–22 nt, was detected for the samples of siRNAs co-purifying with NTAP–P1b proteins, in good agreement with the EMSA and deep sequencing results (Pull down, Fig. 7D). Therefore, the precise correlation between the ability to bind 21-nt siRNAs in vivo and the silencing suppression activity of the P1b mutants analyzed here strongly suggest that interaction with siRNAs plays a key role in the anti-silencing effect mediated by this RSS, and that the LxKA sector forms part of the siRNA binding domain of the protein.

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that the P1b protein of the ipomovirus CVYV suppressed silencing in a very similar manner to the potyviral HCPro, and that, like HCPro and other silencing suppressors, CVYV P1b was able to bind siRNAs in vitro (Valli et al. 2008). In this paper, we unravel specific features of the siRNA binding activity of CVYV P1b, as well as its relevance for the silencing suppression activity of the protein and its effects on the endogenous small RNA populations.

Despite that other strategies have been described to suppress the RNA silencing, binding to dsRNA is a common mechanism used by RSSs. A number of these proteins bind dsRNAs without size specificity, and are thought to protect small RNA precursors from cleavage by Dicer-like enzymes (Bucher et al. 2004; Mérai et al. 2005, 2006). Other RSSs, as potyviral HCPro and tombusviral P19, show strong size-preference for small RNAs of 21 nt, and act by preventing small RNA loading in the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Silhavy et al. 2002; Lakatos et al. 2004; Hemmes et al. 2007). Moreover, it has been suggested that some RSSs, as the protein B2 of the nodavirus Flock house virus and the NSs proteins of some tospoviruses could use both strategies to achieve a more efficient suppression (Chao et al. 2005; Schnettler et al. 2010). By in vitro EMSA analyses we showed that CVYV P1b interacts specifically with dsRNA molecules (Fig. 1), displaying a preference for binding to 21-nt siRNAs when compared to 24- or 26-nt siRNAs (Fig. 2), as it has been previously reported for HCPro and P19 (Lakatos et al. 2006). However, in spite of sharing the same size preference, the RNA binding of these three RSSs appears to have important specific features. Hence, whereas siRNA binding of the P19 protein of the tombusvirus Carnation Italian ringspot virus (CIRV) and the PPV HCPro depends on 5′ terminal phosphoryl groups (Fig. 3D; Vargason et al. 2003), CVYV P1b binds with similar affinity siRNAs with a phosphoryl group or a free OH at their 5′ ends (Fig. 3C). Moreover, it has been found that affinity of HCPro for siRNAs with 2-nt overhangs is higher than that for blunt-ended duplexes (Fig. 3B; Lakatos et al. 2006). However, CVYV P1b is alike P19 and differs from HCPro in the ability to bind with similar efficiency blunt-ended siRNA duplexes and siRNAs with 2-nt overhangs (Fig. 3A; Vargason et al. 2003). These different behaviors, together with the lack of detectable sequence similarity between the three RSSs, highlight how very similar functional strategies, specific binding of 21-nt RNA duplexes, can be attained by independent evolutionary pathways.

The purification by affinity chromatography of the plant-expressed CVYV P1b demonstrated the ability of this RSS to bind small RNAs in vivo. Northern blot (Fig. 4B) and deep sequencing analysis of these small RNAs (Fig. 5) showed a size-preference for molecules of 21–22 nt, confirming the in vitro EMSA results. The deep sequencing analysis also showed that not only siRNAs derived from the agroinfiltrated plasmids, but also plant endogenous small RNAs (Fig. 5B), including known miRNAs (A Valli, L D'Andrea, and JA García, unpubl.), were bound to P1b. The expression of P1b caused a drastic change in the size pattern of endogenous small RNAs of the plant (Fig. 5B). The major peak was at 24 nt in wild-type N. benthamiana plants, as it is usual in angiosperm plant species (Dolgosheina et al. 2008), but shifted to 21 nt upon P1b expression. Although this enrichment in 21-nt small RNAs is probably the result of specific P1b binding and consequent stabilization, additional experiments are necessary to rule out possible effects of P1b in enhancing 21-nt small RNA synthesis or 24-nt small RNA degradation, or in repression of the accumulation of the 24-nt species. It has been shown that binding of different RSSs to small RNAs causes a broad range of positive and negative effects on their levels of accumulation and activity, resulting in drastic development disturbances in the plant (Mallory et al. 2002; Kasschau et al. 2003; Chapman et al. 2004; Dunoyer et al. 2004). Thus, the disturbances caused by P1b in the small RNA populations are expected to produce drastic effects in the physiology of the plant. In agreement with this assumption, Arabidopsis thaliana plants transformed with a transgene expressing CVYV P1b have severe developmental defects that positively correlated with P1b accumulation levels (Valli et al. 2009; A Valli, L D'Andrea, and JA García, unpubl.). Further research is required to associate definite effects of P1b on particular small RNAs with particular phenotypic alterations.

Computer analysis did not identify any canonical RNA binding motif in CVYV P1b, however, a partially conserved domain containing basic amino acids, which were previously associated in specific molecular interactions in the formation of RSS–siRNA complexes (Vargason et al. 2003; Ye et al. 2003; Chao et al. 2005; Lingel et al. 2005; Omarov et al. 2006; Shiboleth et al. 2007; Hemmes et al. 2009; Cao et al. 2010), was identified in P1b-like proteins of different potyvirid (LxKA domain, Fig. 6). Here, we show that some mutations in basic residues of this domain cause a drastic disturbance in the RNA silencing suppression activity of P1b (Fig. 7A,B), and abolish its ability to bind siRNAs in vitro (Fig. 7D). There are some reasons that suggest that the effect of these mutations is not caused by a global effect in the net charge of the protein. First, whereas typical P1 proteins of potyviruses are invariably highly basic, CVYV P1b has an estimated pI of 5.1, similar to that of the rest of P1b-like proteins (Valli et al. 2007). Moreover, the double mutation KR10,11AA, which removes two positive charges in a nonconserved basic domain at the N-terminus of the protein did not affect siRNA binding and silencing suppression activity. Also pointing to structural features of the LxKA domain, rather than solely positive charge, as involved in siRNA binding, we found that the functional effects of replacing R68 by alanine or by leucine, the residue present at this position in SPMMV P1, were quite different. Both mutations prevented siRNA binding in the in vitro EMSA (Fig. 7C); however, in contrast with the drastic effect of R68A on RNA silencing suppression activity, R68L suppressed silencing with high efficiency (Fig. 7A,B). This apparent contradiction was resolved by a pull down assay showing the small RNA bound in vivo by the different mutant proteins. Whereas no (RK68,69AA), or a very little amount of (K61A, R68A, and K69A), siRNAs were pulled down by the silencing suppression-deficient mutants, R68L bound small RNAs in the plant with notable efficiency, although not as high as that of wild-type P1b (Fig. 7D). An important inference of these results is that whereas in vitro EMSA is very useful to analyze specific biochemical features of the siRNA–protein interactions, many functional aspects of the interaction only can be unraveled by studies under in vivo conditions.

The precise correlation that we found between in vivo small RNA binding and silencing suppression activity strongly supports the conclusion that CVYV P1b blocks silencing by interfering with a siRNA function. How this interference takes place is still unknown. The silencing suppression activity of CVYV P1b is not associated in the agroinfiltration experimental assay with a notable change in the levels of total siRNA accumulation (siRNA GF in Fig. 7D), suggesting that this RSS neither disturbs siRNA synthesis nor enhances their degradation. However, the levels of secondary RNAs were much lower in leaves expressing P1b variants exhibiting silencing suppression activity than in those expressing inactive proteins (siRNA P in Fig. 7D). A similar effect has been reported for the potyviral HCPro (Moissiard et al. 2007; Mlotshwa et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2008). This specific effect on secondary siRNAs accumulation is in agreement with a similar silencing suppression mechanism of P1b and HCPro, which is based on sequestration of small RNAs preventing their incorporation in silencing effector complexes and their contribution to silencing amplification steps.

Sequestration of siRNAs appears to be a successful method to counteract silencing and is likely the main suppression strategy developed by potyvirid. However, recent results show that other silencing suppression mechanisms are also able to support potyvirid infection. Indeed, the P1 protein of SPMMV, which is a homolog of CVYV P1b, suppresses silencing by binding to AGO1 and inhibition of RISC activity rather than by RNA binding (Giner et al. 2010). It will be very interesting to unravel how highly similar proteins have adopted these quite different suppression mechanisms, and how very similar viruses are able to use them to neutralize anti-viral silencing. Moreover, if the ipomoviral P1 RSSs play additional roles independent of silencing suppression, as HCPro does, understanding the structural and functional relationships of these activities will be an exciting research challenge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids

GATEWAY technology (Invitrogen) was applied to construct plasmids expressing tagged forms of mutant CVYV P1b, using pDONR-207 (Invitrogen) as donor vector and pNTAPi (provided by Michael Fromm, University of Nebraska) (Rohila et al. 2004) as destination vector. p35S–NTAP–P1b (wild-type and RK68,69AA mutant) and p35S-P1HC has been previously described (Valli et al. 2006, 2008). Site-directed mutagenesis of P1b was carried out by two PCR steps as described by Herlitze and Koenen (1990). Primers and the template used for PCR amplification and site-directed mutagenesis of P1b sequences to generate the different entry vectors are listed in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

Expression vectors producing mutant versions of NTAP–P1b (derivatives of p35S–NTAP–P1b) were constructed by LR clonase reactions between pDONR-nonAUGP1b entry vectors (Supplemental Table S1) and the destination vector pNTAPi. Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 strain carrying p35S:GFP (Haseloff et al. 1997) plus pCH32 (Hamilton et al. 1996), and p35S:GF-IR (Schwach et al. 2005) were previously described.

Sequence analysis

Sequence alignment of P1 sequences from CVYV (GenBank accession no. AY578085), SqVYV (GenBank accession no. EU259611), CBSV (GenBank accession no. FJ039520), SPMMV (GenBank accession no. Z73124), Triticum mosaic virus (TriMV, GenBank accession no. FJ263671), Sugarcane streak mosaic virus (SCSMV, GenBank accession no. ADE34528), Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV, GenBank accession no. AF057533), Oat necrotic mottle virus (ONMV, GenBank accession no. AY377938), Wheat eqlid mosaic virus (WEqMV, GenBank accession no. EF608612), Brome streak mosaic virus (BStMV, GenBank accession no. Z48506), and Blackberry virus Y (BVY, GenBank accession no. AY994084) was carried out by using the DNASTAR MegAlign program and refined by manual editing. Plots of charge density at pH 7 were made with the DNASTAR Protean program with a window size of five residues.

Agroinfiltration and fluorescence imaging

Nicotiana benthamiana plants were infiltrated with A. tumefaciens C58C1 strain carrying the indicated plasmids as previously described (Valli et al. 2006). GFP fluorescence was observed under a Leica MZ FLIII fluorescence microscope (Leica) with excitation and barrier filters of 480/40 and 510 nm, respectively. Pictures of GFP were caught with an Olympus DP 70 camera and the software DP Controller and DP manager (Olympus Optical).

Purification and detection of TAP-tagged P1b proteins

Purification of NTAP–P1b proteins by affinity chromatography with calmodulin-Sepharose, and the detections by Western blot assay were performed according to Valli et al. (2008).

RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis

Samples of large and small RNAs were prepared from agroinfiltrated leaf tissue as previously described (Valli et al. 2006). For the analysis of small RNAs interacting with P1b in vivo, wild-type and mutant NTAP–P1b were purified by affinity chromatography in calmoduline-Sepharose beads (Valli et al. 2008). Protein fractions were mixed with 0.5 volumes of RNA extraction buffer (0.1 M LiCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM EDTA pH 8 and 1% SDS) and 0.5 volumes of phenol. The nucleic acids were then precipitated from the aqueous phase with ethanol, using GlycoBlue (Ambion) as a carrier, and resuspended in water.

Samples were subjected to Northern blot analysis as described (Valli et al. 2006). GFP siRNA were detected with 32P-labeled GF and P riboprobes, which were prepared by transcription with SP6 RNA polymerase from SacII-linearized pGEMT-GF and pGEMT-P, respectively. These plasmids contain the nucleotides 4 to 403 (GF) and 404 to 717 (P) of the GFP gene cloned in pGEM-T.

High-throughput sequencing of Nicotiana benthamiana small RNAs

Production of small RNA libraries was done according to Mosher et al. (2009). For leaf libraries, 100 μg of total RNA were run over miRVana kit (Ambion) to enrich the samples in RNAs shorter than 200 nt, whereas this step was omitted for nucleic acids that copurify with NTAP–P1b.

Purified libraries were sequenced on an Illumina Genome Analyser (Illumina) and reads were processed by Sequence Pre-processing, Filter, and miRProf tools (http://srna-tools.cmp.uea.ac.uk; Moxon et al. 2008) to remove the 3′ adaptor, discard known tRNA and rRNA molecules, and detect conserved miRNAs, respectively. Identification of reads matching the pNTAP–P1b plasmid sequence and treatment of the data to present them as histograms was carried out using in-house developed PHP scripts.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Synthetic nucleic acids (Sigma) used for EMSAs are listed in Supplemental Table S3. They were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK, Promega). Nonlabeled 5′-phosphorylated siRNAs were also obtained by PNK treatment using ATP as phosphoryl group donor. Preparation of crude protein extracts, incubation for binding reactions, and the resolution of complexes were made as described (Valli et al. 2008).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Elvira Dominguez by technical assistance, and to Michael Fromm (University of Nebraska) for providing the destination vector pNTAPi. This work was supported by grant nos. BIO2007-67283 and BIO2010-18541from Spanish MICINN, SAL/0185/2006 from Comunidad de Madrid, and KBBE-204429 from European Union. A.V. was a recipient of an I3P fellowship from CSIC-Fondo Social Europeo.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2510611.

REFERENCES

- Anandalakshmi R, Pruss GJ, Ge X, Marathe R, Mallory AC, Smith TH, Vance VB 1998. A viral suppressor of gene silencing in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 13079–13084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigneti G, Voinnet O, Li WX, Ji LH, Ding SW, Baulcombe DC 1998. Viral pathogenicity determinants are suppressors of transgene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. EMBO J 17: 6739–6746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bucher E, Hemmes H, de Haan P, Goldbach R, Prins M 2004. The influenza A virus NS1 protein binds small interfering RNAs and suppresses RNA silencing in plants. J Gen Virol 85: 983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Ye X, Willie K, Lin J, Zhang X, Redinbaugh MG, Simon AE, Morris TJ, Qu F 2010. The capsid protein of Turnip crinkle virus overcomes two separate defense barriers to facilitate systemic movement of the virus in Arabidopsis. J Virol 84: 7793–7802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao JA, Lee JH, Chapados BR, Debler EW, Schneemann A, Williamson JR 2005. Dual modes of RNA-silencing suppression by flock house virus protein B2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12: 952–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman EJ, Prokhnevsky AI, Gopinath K, Dolja VV, Carrington JC 2004. Viral RNA silencing suppressors inhibit the microRNA pathway at an intermediate step. Genes Dev 18: 1179–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey SN, Al-Kaff N, Lángara A, Turner DS 1997. Plants combat infection by gene silencing. Nature 385: 781–782 [Google Scholar]

- Csorba T, Pantaleo V, Burgyán J 2009. RNA silencing: an antiviral mechanism. Adv Virus Res 75: 35–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Jones JDG 2001. Plant pathogens and integrated defense responses to infection. Nature 411: 826–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleris A, Gallego-Bartolome J, Bao JS, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC, Voinnet O 2006. Hierarchical action and inhibition of plant Dicer-like proteins in antiviral defense. Science 313: 68–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Pendon JA, Ding SW 2008. Direct and indirect roles of viral suppressors of RNA silencing in pathogenesis. Annu Rev Phytopathol 46: 303–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding SW, Voinnet O 2007. Antiviral immunity directed by small RNAs. Cell 130: 413–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolgosheina EV, Morin RD, Aksay G, Sahinalp SC, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Mattsson J, Unrau PJ 2008. Conifers have a unique small RNA silencing signature. RNA 14: 1508–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunoyer P, Lecellier CH, Parizotto EA, Himber C, Voinnet O 2004. Probing the microRNA and small interfering RNA pathways with virus-encoded suppressors of RNA silencing. Plant Cell 16: 1235–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Fellers JP, Seifers D, Ryba-White M, Martin TJ 2009. The complete genome sequence of Triticum mosaic virus, a new wheat-infecting virus of the High Plains. Arch Virol 154: 1511–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ruiz H, Takeda A, Chapman EJ, Sullivan CM, Fahlgren N, Brempelis KJ, Carrington JC 2010. Arabidopsis RNA-dependent RNA polymerases and Dicer-like proteins in antiviral defense and small interfering RNA biogenesis during Turnip mosaic virus infection. Plant Cell 22: 481–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giner A, Lakatos L, Garcia-Chapa M, Lopez-Moya JJ, Burgyan J 2010. Viral protein inhibits RISC activity by argonaute binding through conserved WG/GW motifs. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000996 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Frary A, Lewis C, Tanksley SD 1996. Stable transfer of intact high molecular weight DNA into plant chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 9975–9979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseloff J, Siemering KR, Prasher DC, Hodge S 1997. Removal of a cryptic intron and subcellular localization of green fluorescent protein are required to mark transgenic Arabidopsis plants brightly. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 2122–2127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelda Z, Hornyik C, Crescenzi A, Burgyan J 2003. In situ characterization of Cymbidium ringspot tombusvirus infection-induced posttranscriptional gene silencing in Nicotiana benthamiana. J Virol 77: 6082–6086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmes H, Lakatos L, Goldbach R, Burgyan J, Prins M 2007. The NS3 protein of Rice hoja blanca tenuivirus suppresses RNA silencing in plant and insect hosts by efficiently binding both siRNAs and miRNAs. RNA 13: 1079–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmes H, Kaaij L, Lohuis D, Prins M, Goldbacht R, Schnettler E 2009. Binding of small interfering RNA molecules is crucial for RNA interference suppressor activity of rice hoja blanca virus NS3 in plants. J Gen Virol 90: 1762–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Koenen M 1990. A general and rapid mutagenesis method using polymerase chain reaction. Gene 91: 143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen D, Martín G, Velasco L, Gómez P, Segundo E, Ruiz L, Cuadrado IM 2005. Absence of a coding region for the helper component-proteinase in the genome of cucumber vein yellowing virus, a whitefly-transmitted member of the Potyviridae. Arch Virol 150: 1439–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JDG, Dangl JL 2006. The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasschau KD, Carrington JC 1998. A counterdefensive strategy of plant viruses: Suppression of posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell 95: 461–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasschau KD, Xie ZX, Allen E, Llave C, Chapman EJ, Krizan KA, Carrington JC 2003. P1/HC-Pro, a viral suppressor of RNA silencing, interferes with Arabidopsis development and miRNA function. Dev Cell 4: 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos L, Szittya G, Silhavy D, Burgyan J 2004. Molecular mechanism of RNA silencing suppression mediated by p19 protein of tombusviruses. EMBO J 23: 876–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos L, Csorba T, Pantaleo V, Chapman EJ, Carrington JC, Liu YP, Dolja VV, Calvino LF, López-Moya JJ, Burgyán J 2006. Small RNA binding is a common strategy to suppress RNA silencing by several viral suppressors. EMBO J 25: 2768–2780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WM, Hilf ME, Webb SE, Baker CA, Adkins S 2008. Presence of P1b and absence of HC-Pro in Squash vein yellowing virus suggests a general feature of the genus Ipomovirus in the family Potyviridae. Virus Res 135: 213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingel A, Simon B, Izaurralde E, Sattler M 2005. The structure of the flock house virus B2 protein, a viral suppressor of RNA interference, shows a novel mode of double-stranded RNA recognition. EMBO Rep 6: 1149–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory AC, Reinhart BJ, Bartel D, Vance VB, Bowman LH 2002. A viral suppressor of RNA silencing differentially regulates the accumulation of short interfering RNAs and micro-RNAs in tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 15228–15233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbanzibwa DR, Tian YP, Mukasa SB, Valkonen JPT 2009. Cassava brown streak virus (Potyviridae) encodes a putative Maf/HAM1 pyrophosphatase implicated in reduction of mutations and a P1 proteinase that suppresses RNA silencing but contains no HC-Pro. J Virol 83: 6934–6940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mérai Z, Kerényi Z, Molnár A, Barta E, Válóczi A, Bisztray G, Havelda Z, Burgyán J, Silhavy D 2005. Aureusvirus P14 is an efficient RNA silencing suppressor that binds double-stranded RNAs without size specificity. J Virol 79: 7217–7226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mérai Z, Kerényi Z, Kertész S, Magna M, Lakatos L, Silhavy D 2006. Double-stranded RNA binding may be a general plant RNA viral strategy to suppress RNA silencing. J Virol 80: 5747–5756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlotshwa S, Pruss GJ, Peragine A, Endres MW, Li J, Chen X, Poethig RS, Bowman LH, Vance V 2008. DICER-LIKE2 plays a primary role in transitive silencing of transgenes in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 3: e1755 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moissiard G, Parizotto EA, Himber C, Voinnet O 2007. Transitivity in Arabidopsis can be primed, requires the redundant action of the antiviral Dicer-like 4 and Dicer-like 2, and is compromised by viral-encoded suppressor proteins. RNA 13: 1268–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher RA, Melnyk CW, Kelly KA, Dunn RM, Studholme DJ, Baulcombe DC 2009. Uniparental expression of PolIV-dependent siRNAs in developing endosperm of Arabidopsis. Nature 460: 283–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxon S, Schwach F, MacLean D, Dalmay T, Studholme DJ, Moulton V 2008. A toolkit for analysing large-scale plant small RNA datasets. Bioinformatics 24: 2252–2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omarov R, Sparks K, Smith L, Zindovic J, Scholthof HB 2006. Biological relevance of a stable biochemical interaction between the tombusvirus-encoded p19 and short interfering RNAs. J Virol 80: 3000–3008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu F, Morris TJ 2002. Efficient infection of Nicotiana benthamiana by Tomato bushy stunt virus is facilitated by the coat protein and maintained by p19 through suppression of gene silencing. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 15: 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff F, Harrison BD, Baulcombe DC 1997. A similarity between viral defense and gene silencing in plants. Science 276: 1558–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohila JS, Chen M, Cerny R, Fromm ME 2004. Improved tandem affinity purification tag and methods for isolation of protein heterocomplexes from plants. Plant J 38: 172–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BM, Pruss GJ, Vance VB 2004. Plant viral suppressors of RNA silencing. Virus Res 102: 97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sáenz P, Salvador B, Simón-Mateo C, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC, García JA 2002. Host-specific involvement of the HC protein in the long-distance movement of potyviruses. J Virol 76: 1922–1931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler E, Hemmes H, Huismann R, Goldbach R, Prins M, Kormelink R 2010. Diverging affinity of tospovirus RNA silencing suppressor proteins, NSs, for various RNA duplex molecules. J Virol 84: 11542–11554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwach F, Vaistij FE, Jones L, Baulcombe DC 2005. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase prevents meristem invasion by potato virus X and is required for the activity but not the production of a systemic silencing signal. Plant Physiol 138: 1842–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiboleth YM, Haronsky E, Leibman D, Arazi T, Wassenegger M, Whitham SA, Gaba V, Gal-On A 2007. The conserved FRNK box in HC-Pro, a plant viral suppressor of gene silencing, is required for small RNA binding and mediates symptom development. J Virol 81: 13135–13148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhavy D, Molnár A, Lucioli A, Szittya G, Hornyik C, Tavazza M, Burgyán J 2002. A viral protein suppresses RNA silencing and binds silencing-generated, 21- to 25-nucleotide double-stranded RNAs. EMBO J 21: 3070–3080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soosaar JLM, Burch-Smith TM, Dinesh-Kumar SP 2005. Mechanisms of plant resistance to viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 3: 789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susaimuthu J, Tzanetakis IE, Gergerich RC, Martin RR 2008. A member of a new genus in the Potyviridae infects Rubus. Virus Res 131: 145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatineni S, Ziems AD, Wegulo SN, French R 2009. Triticum mosaic virus: A distinct member of the family Potyviridae with an unusually long leader sequence. Phytopathology 99: 943–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valli A, Martín-Hernández AM, López-Moya JJ, García JA 2006. RNA silencing suppression by a second copy of the P1 serine protease of Cucumber vein yellowing ipomovirus (CVYV), a member of the family Potyviridae that lacks the cysteine protease HCPro. J Virol 80: 10055–10063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valli A, López-Moya JJ, García JA 2007. Recombination and gene duplication in the evolutionary diversification of P1 proteins in the family Potyviridae. J Gen Virol 88: 1016–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valli A, Dujovny G, García JA 2008. Protease activity, self interaction, and small interfering RNA binding of the silencing suppressor P1b from Cucumber vein yellowing ipomovirus. J Virol 82: 974–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valli A, López-Moya JJ, García JA 2009. RNA silencing and its suppressors in the plant-virus interplay. In Encyclopedia of life sciences (ELS). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester [Google Scholar]

- Vargason JM, Szittya G, Burgyan J, Tanaka Hall TM 2003. Size selective recognition of siRNA by an RNA silencing suppressor. Cell 115: 799–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O 2001. RNA silencing as a plant immune system against viruses. Trends Genet 17: 449–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XB, Wu Q, Ito T, Cillo F, Li WX, Chen X, Yu JL, Ding SW 2010. RNAi-mediated viral immunity requires amplification of virus-derived siRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 484–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K, Malinina L, Patel DJ 2003. Recognition of small interfering RNA by a viral suppressor of RNA silencing. Nature 426: 874–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Du P, Lu L, Xiao Q, Wang W, Cao X, Ren B, Wei C, Li Y 2008. Contrasting effects of HC-Pro and 2b viral suppressors from Sugarcane mosaic virus and Tomato aspermy cucumovirus on the accumulation of siRNAs. Virology 374: 351–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]