Abstract

Apoptosis is an essential process for the maintenance of normal physiology. The ability to non-invasively image apoptosis in living animals would provide unique insights into its role in normal and disease processes. Herein, a recombinant reporter consisting of beta galactosidase gene flanked by two ER regulatory domains and intervening DEVD sequences was constructed to serve as a tool for invivo assessment of apoptotic activity. The results demonstrate that when expressed in its intact form, the hybrid reporter had undetectable LACZ activity. Caspase 3 activation in response to an apoptotic stimulus resulted in cleavage of the reporter, and thereby reconstitution of LACZ activity. Enzymatic activation of the reporter during an apoptotic event enabled non-invasive measurement of LACZ activity in living cells, which correlated with traditional measures of apoptosis in a dose and time dependent manner. Furthermore, using a near-infrared fluorescent substrate of beta galactosidase (DDAOG), non-invasive invivo imaging of apoptosis was achieved using a xenograft tumor model in response to pro-apoptotic therapy. Lastly, a transgenic mouse model was developed expressing the ER-LACZ-ER reporter within the skin. This reporter and transgenic mouse could serve as a unique tool for the study of apoptosis in living cells and animals especially in context of skin biology.

Keywords: Molecular imaging, proteaseiImaging, caspase 3, beta galactosidase

Introduction

Apoptosis is a highly conserved, genetically programmed cell death process that removes unwanted or damaged cells. Apoptosis is distinguished from necrosis based on the fact that apoptosis results from activation of specific signaling pathways, which include the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. The extrinsic pathway involves activation of cell surface death receptors [e.g. Fas-R and Tumor Necrotic Factor Alpha (TNFα) receptors by their respective ligands [e.g. Fas-L and TNF-α related apoptosis inducting ligand (TRAIL)], whereas the intrinsic pathway is generally mediated through mitochondrial events that lead to Apaf-1 and cytochrome c mediated activation of the apoptotic machinery (Bhojani et al., 2003). In either case, activation of specific effector molecules (e.g. caspases) culminates in cell death that can be morphologically distinguished from necrosis. Apoptotic death is generally characterized by chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, blebbing of the cytoplasmic membrane and release of apoptotic bodies etc. (Bhojani et al., 2003; Hengartner, 2000; Nicholson and Thornberry, 2003; Strasser et al., 2000).

The consequence of both the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways is the activation of members of the caspase family of proteases, in particular caspase 3, which in turn can cleave a large number of intracellular substrates (Botchkareva et al., 2006; Strasser et al., 2000). A variety of stimuli, such as changes in the levels of growth factors, loss of adhesion in cells, DNA damage or activation of pro-apoptotic receptors, can all initiate apoptosis (Afford and Randhawa, 2000; Botchkareva et al., 2006) and dysregulation of apoptosis can lead to either excessive elimination of cells or prolonged survival of cells. Thus, dysfunctional apoptosis can have many deleterious effects resulting in pathogenesis of various diseases such as cancer, AIDS, neurodegenerative disorders, myelodysplastic syndromes, ischemia/reperfusion injury, and autoimmune diseases (Bhojani et al., 2003; Kaufmann and Gores, 2000; Loro et al., 2005; Nicholson and Thornberry, 2003; Shi, 2002; Strasser et al., 2000).

The importance of apoptosis in self-renewal within the skin and hair in response to environmental damage, as well as in diseases of keratinocytes, is now becoming apparent (Raj et al., 2006). It has been shown recently that keratinocytes possess reversible physiologic defenses against spontaneous and ultraviolet light-induced apoptosis (Norris et al., 1997; Pincelli et al., 1997). Similarly, human melanocytes are protected from ultraviolet-induced apoptosis by neurotrophic proteins (Zhai et al., 1996) secreted in a paracrine fashion by other skin cells (Yaar et al., 1994). On the other hand, loss of programmed cell death may be involved in the development of skin cancer (Botchkareva et al., 2006). Indeed, in ultraviolet-induced skin cancer, inactivation of the tumor suppressor gene p53 reduces the appearance of "sunburn cells", apoptotic keratinocytes that might have incurred mutations and thus are to be eliminated (Ziegler et al., 1994). BCL2 is a major anti-apoptotic protein (Kroemer, 1997) that is expressed in normal keratinocytes and melanocytes (Rodriguez-Villanueva et al., 1995). Aberrant expression of BCL2 has been involved in tumor development (Fanidi et al., 1992), and changes in BCL2 levels have been observed in melanoma (Kanter-Lewensohn et al., 1997) and non-melanoma (Cerroni and Kerl, 1994; Morales-Ducret et al., 1995) skin cancers.

The ability to non-invasively image apoptosis would provide unique insight into the pathogenesis of disorders referenced above. To this end, we here describe a reporter wherein fluorescence imaging can be used as a surrogate for caspase activation, and therefore apoptosis. This reporter is an adaptation of a bioluminescence-based reporter described previously (Laxman et al., 2002). Due to the lack of resolution and dependence on cofactors like ATP when luciferase is used as a reporter, we have modified this reporter for imaging of apoptosis using fluorescence imaging. In the current study we describe the development of a beta galactosidase-based reporter molecule whose activity is dependent on caspase 3 activity. In this reporter, the beta galactosidase sequence is flanked by a protease cleavage site for caspase 3 (DEVD) on either side of the coding sequence that is further fused with two ER domains on each end (Laxman et al., 2002). Expression of this reporter in cells enabled non-invasive imaging in live cells as well as in tumor xenografts and transgenic animals wherein the reporter is expressed in the skin using the keratin 5 (KRT5) promoter. These transgenic animals provide the ability to image apoptosis in a sensitive, specific and dynamic manner, and thus can be used to obtain unique insights into the role of apoptosis in biology of the skin (e.g. in wound healing) as well as in diseases of the skin (e.g. in ultraviolet light induced DNA damage and cellular transformation).

Results

Characterization of the ER-LacZ-ER reporter

The functional basis of the ER-LACZ-ER reporter is based on the fact that beta galactosidase is active as a tetramer. We hypothesized that fusion of the estrogen receptor regulatory domain (ER) at the amino- and carboxyl- termini (Figure 1A) of the protein would result in a protein wherein multimerization is stearically prevented and thus inhibits LACZ (beta galactosidase) activity. Proteolytic release of the Estrogen Regulatory (ER) domains in a caspase 3 dependent manner was enabled by the inclusion of the DEVD sequence between the ER and the LACZ coding sequences, therefore enabling functional activation of beta galactosidase (Figure 1B) in the presence of active caspase 3 (during apoptosis).

Figure 1. Construction and validation of the recombinant reporter molecule ER-LACZ-ER.

(A) A schematic representation of the design of the ER-LACZ-ER reporter wherein the beta galactosidase is flanked by ER domains at the amino- and carboxyl-termini with an intervening DEVD sequence. (B) The proposed mechanism of action of the ER-LACZ-ER reporter. In its intact form, the reporter shows minimal LACZ activity due to ER-mediated stearic hindrance preventing tetramerization of the enzyme. Activation of the reporter in the presence of an apoptotic stimulus releases the ER domains from individual monomers due to a caspase 3 dependent cleavage at the DEVD sequence, allowing for the homodimerazation of the active beta galactosidase tetramer. (C) Western blot analysis of TRAIL(200ng/ml) treated D54 glioma cells expressing the reporter showed partial cleavage of the ER-LACZ-ER reporter at 1hr (150KDa) and presence of the free LACZ (110KDa) at 2.5 hr. Appearance of active caspase 3 at these time points was consistent with the cleavage of the reporter at the caspase 3 dependent DEVD sequence.

To validate this approach, D54 glioma cells stably expressing the ER-LACZ-ER reporter were treated with TRAIL. In untreated cells (0 hr), the reporter was detected as a 190kDa species (Figure 1C) but 1 hr after TRAIL treatment, the 190 kDa band dissipated with a concomitant appearance of a 150kDa species corresponding to beta galactosidase (110kDa) fused to a single ER domain (40kDa). At later time points, the 110kDa species of free beta galactosidase was detected. Analysis of caspase 3 activation in these samples confirmed the presence of active caspase 3 at both the 1 and 2.5 h time points.

To investigate the consequence of these caspase 3 dependent cleavage events on reporter activity, LACZ activity was monitored in D54 cells expressing wild type beta galactosidase (D54/LACZ), untreated D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells as well as TRAIL treated D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells. As shown in Figure 2A, LACZ activity was readily detected in D54/LACZ cells and remained essentially unchanged for the entire 6 hr time course, while no significant activity was detected in the untreated D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells. In response to TRAIL treatment, D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells demonstrated a significant increase in LACZ activity at the earliest time point (2 hr) which increased at subsequence time points (Figure 2A). Figure 2B demonstrates that the activation of LACZ activity in D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells was dose dependent and that doses beyond 100ng/ml of TRAIL appear saturating.

Figure 2. Activation of beta galactosidase in response to apoptosis.

(A) Time-dependent activation of beta galactosidase activity in ER-LACZ-ER expressing cells. D54 cells expressing wild-type LACZ (D54/LACZ) or the ER-LACZ-ER reporter were treated in the presence of 100 ng/ml TRAIL or untreated (Control). At each time point LACZ activity was measured using the DDAOG substrate and live cells. (B) Activation of LACZ in D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells following TRAIL treatment in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Fluorescent microscopic imaging showing time dependent activation of LACZ following treatment with 200ng/ml of TRAIL. The presence of the DDAOG (intact) substrate was imaged by excitation at 488 nm (pseudocolored in green), while production of the DDAO (cleaved) product in a beta galactosidase dependent manner was imaged by excitation at 633nm (pseudocolored in red). (D) A dose dependent increase in LACZ activity was determined as in B.

To demonstrate the utility of the reporter in live cell imaging of apoptosis, D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells were treated with TRAIL and imaged at various times using DDAOG (9H-{1,3-dichloro-9,9-dimethylacridin-2-one-7-yl} ß-D-galactopyranoside). DDAOG is a chromogenic substrate made by conjugating beta galactosidase and (7-hydroxy-9H-{1,3-dichloro-9,9-dimethylacridin-2-one) (DDAO). Cleavage of DDAOG into DDAO by beta galactosidase produces a far red fluorescent signal. The cleaved substrate DDAO emits a 50nm red shift enabling specific detection of the cleaved substrate from the intact substrate (DDAOG) (Tung et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 2C, control untreated cells (0 hr) failed to convert any detectable levels of DDAOG to DDAO (lack of red fluorescence) indicating the absence of LACZ activity. Low levels of DDAO were detected at 1hr time point which accumulated over time. Significant DDAO accumulation (5 hr and 24 hr) correlated with the appearance of apoptotic, rounded morphology of the D54 cells. A dose response study (Figure 2D) confirmed the quantitative nature of the reporter and also demonstrated that in the absence of an apoptotic stimulus, DDAOG to DDAO conversion was undetectable. However, in the presence of as little as 25 ng/ml of TRAIL, significant activity was detected that increased with increasing doses of the apoptotic stimulus. At the highest doses, DDAO containing cells were also morphologically apoptotic.

To investigate the utility of the reporter in live animals, preliminary studies were conducted wherein D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells were implanted subcutaneously into nude mice. When the tumors were approximately 100 mm3 in size, treatment of the animals with TRAIL resulted in a 350% increase in fluorescence activity from DDAO production as compared to pre-treatment levels (Figure 3A). No significant change in the fluorescence activity was detected in control animals treated with saline over this time interval whereas the TRAIL-treated cohort of animals had significantly increased fluorescence activity over the control group (p<.001) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. In vivo imaging of apoptosis in D54/ER-LACZ-ER xenografts.

(A) D54/ER-LACZ-ER glioma cell lines were used to generate subcutaneous tumor xenografts. Fluorescence imaging was achieved using a Maestro imaging workstation as described in the material and methods section. Upon DDAOG administration, images were acquired prior to (T=O hr) and 12 hr (T=12hr) after treatment with saline (control) or TRAIL treatment. (B) The average percentage change in fluorescence activity in saline-treated (control) and TRAIL-treated animals was found to be statistically different (p < .001). Error bars represent ±SD, n=5.

Expression of ER-LacZ-ER reporter in transgenic mice

In an effort to develop a mouse model wherein apoptosis could be monitored non-invasively and dynamically in the skin, we constructed a transgenic mouse where ER-LACZ-ER reporter was driven by the keratinocyte specific KRT5 promoter. The structure of the expression cassette is shown in Figure 4A. Analysis of tail genomic DNA in the founders revealed the presence of a 540 base pair sequence by PCR in transgenic animals but not control animals (Figure 4B). Immnohistochemical analysis of skin tissue from transgenic animals revealed the presence of LACZ immunoreactivity in epidermal cells which corresponded to cells that had KRT5 positive staining (Figure 4C, right). Control animals failed to show beta galactosidase specific immunoreactivity (Figure 4C, left).

Figure 4. Transgenic mouse model for skin specific expression of the ER-LACZ-ER reporter.

(A) Schematic representation of the transgenic construct containing the ER-LACZ-ER coding sequence under the transcriptional control of the keratin 5 (KRT5) promoter. (B) Presence of the transgene was determined by PCR analysis. Tail derived genomic DNA from transgenic animals (Transgene +) yielded a 540bp band while non-transgenic animals did not yield a corresponding band. A plasmid containing the transgenic cassette was used as a positive control (pBKER-LACZ-ER) and water (no template) as a negative control. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of formalin fixed paraffin embedded dorsal skin sections from non-transgenic (control) and transgenic mice (ER-LACZ-ER Transgenic). Presence of LACZ protein and KRT5 was detected using the appropriate antisera. DAPI staining was used to identify nuclei. In control animals, KRT5 staining but not LACZ staining was observed, while in transgenic animals, KRT5 staining and LACZ staining was detected in similar populations within the section.

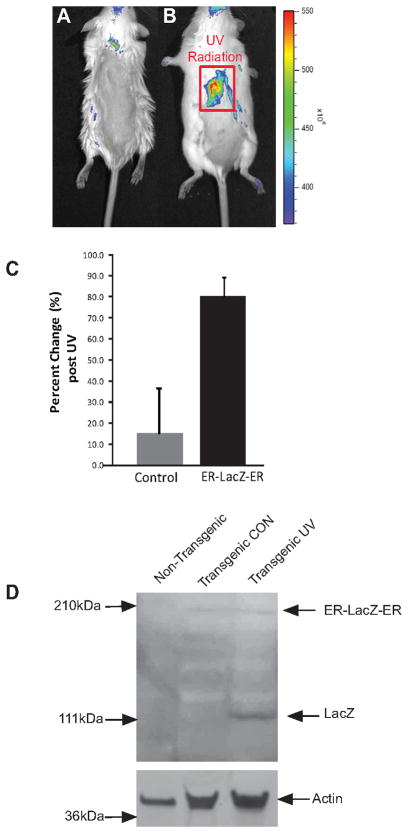

To investigate whether the reporter in the transgenic animals was conditionally activated in response to an apoptotic stimulus, shaved mice were UV-irradiated and fluorescence imaging was done upon administration of the DDAOG substrate. No significant DDAO fluorescence was detected in mock treated animals, but in UV-irradiated animals, a significant increase in DDAO fluorescence was observed at 24 hr compared to pre-treatment (Figures 5A and 5B, respectively). In a cohort of five animals, a statistically significant 1.8 fold increase in DDAO fluorescence activity was detected over mock irradiated animals (Figure 5C) (p < .001). Surgical removal of skin from non-transgenic as well as unirradiated (transgenic CON) and UV-irradiated (transgenic UV) transgenic animals revealed the presence of the 190 kDa ER-LacZ-ER polypeptide in the transgenic animals that was not present in the control animals (Figure 5D). In addition, the active liberated form of the LACZ (approx 110 kDa) was observed in the UV-irradiated animals and not in the un-irradiated animals (Figure 5D). To validate the imaging studies, we conducted immunohistologic studies using an antibody specific for active caspase 3 to demonstrate the presence of apoptotic activity within the UV-irradiated mouse skin samples. As shown in Figure 6, no significant staining was observed in unirradiated animals while UV-treated animals had significant levels of active caspase 3 positivity within the epidermal cells.

Figure 5. Imaging of UV-induced apoposis in transgenic animals.

Transgenic mice were shaved and UVB-irradiated (B) or mock irradiated (A). The irradiated area is outlined as a red square. After irradiation, mice were injected with the fluorescent substrate DDAOG and imaged using a Xenogen IVIS system as described above. As compared to the control animals, the UVB treated animals showed a significant fluorescent signal 24hr after radiation. (C) Control animals (open bar) showed an approximately 10% change in fluorescence, while UV-irradiated animals (solid bar) had an 80% mean increase in fluorescence activity. Error bars represent ±SD, n=5 animals per group. (D) Western blot analysis from skin extracts of non transgenic and non-irradiated transgenic (Transgenic CON) as well as irradiated transgenic (Transgenic UV) mice confirmed the presence of ER-LACZ-ER (190kDa) reporter in transgenic animals. Moreover, active LACZ (110 kDa) was only present in UV irradiated but not in control transgenic mice confirming UV-dependent activation of the reporter. Actin was used as a loading control.

Figure 6. Generation of active caspase 3 within proliferating cells of the skin.

(A) Imunohistological studies showing presence of active caspase 3 within the UV treated transgenic samples (bottom) and not in mock-irradiated (control) animals (top). Proliferating populations within the skin including the basal layer of the epidermis and the outer root sheath of the hair follicles (arrows) had the highest levels of active caspase 3. (B) Correlation of caspase 3 positivity and LACZ activity. Cryosections of un-irradiated (control) and UV-irradiated transgenic animals were stained with X-gal and an antibody specific for activated caspase 3. Co-localization of beta galactosidase activity and active caspase 3 staining was observed within the epidermal cells of treated animals (shown by arrows) but not in the control animals.

Lastly, skin sections from an untreated control mouse and a UV-irradiated mouse were stained using X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galadctopyranoside) to identify cells that possessed both active beta galactosidase as well as with an antibody specific for active caspase 3. As shown in Figure 6B, untreated control cells had no significant staining for active caspase 3 as well as low LACZ activity. These results reveal co-localization of the beta galactosidase activity with activation of caspase 3 thus directly correlating detection of the fluorescent signal with apoptosis using this molecular imaging reporter system.

Discussion

Two apoptotic pathways of physiologic importance have been identified in the skin. The first involves ultraviolet radiation in sunlight which is the principal carcinogen, serving as initiator and promoter of most skin tumors (Ziegler et al., 1994). UV radiation elicits p53-dependent apoptosis in DNA-damaged keratinocytes (sunburn cells), presumably as a “guardian of the genome” response to eradicate precancerous cells in the skin (Brash, 1996). This p53-driven response, termed “cellular proofreading” (Brash, 1996), eliminates damaged cells rather than repairs damaged DNA in cells. Mice deficient in p53 (p53-null) have reduced sunburn cell formation and increased susceptibility to UV-induced skin carcinogenesis (Li et al., 1998; Ziegler et al., 1994), implicating apoptosis as a critical event in skin carcinogenesis. The second pathway involves activation of the cell surface death receptor fas. Defects in this pathway have been associated with skin diseases including eczymatous dermatitis, toxic epidermal necrolysis and graft versus host disease (reviewed in (Raj et al., 2006)).

Orchestration of the apoptotic program is critical for the maintenance of homeostasis within the skin. The skin barrier is composed mainly of the epidermis, which is continuously renewed by the mitotic activity of stem cells in the basal layer, which provides new keratinocytes. Cornification, a programmed cell death process, involves withdrawal of keratinocytes from the cell cycle, detachment from the basement membrane and terminal differentiation to become corneocytes in the outer layers of the epidermis, providing a critical barrier function. Imbalances in the production of keratinocytes or the formation of the cornified epithelium can disrupt the barrier function of the skin and are responsible for many skin disorders. Since our understanding of the role of keratinocyte apoptosis in normal epidermal development and in various skin diseases is primarily from studies in cultured cells, validation of these concepts in animal models is needed so that apoptosis-based therapeutic interventions can be developed and validated.

Here we describe a mouse model wherein apoptosis can be non-invasively and quantitatively evaluated macroscopically in live animals as well as microscopically in tissue sections and living cells. This will enable the translation of laboratory studies into the development of therapeutics that modulate apoptosis with the goal of treating diseases like skin cancer, dermatitis and graft versus host disease. Adapting from our previously described reporter for imaging of apoptosis using bioluminescence (Laxman, et al., 2002), we present results in the current study using fluorescence imaging as a readout of beta galactosidase activity that validate the specificity, sensitivity as well as noninvasive quantitative nature of the reporter.

KRT5 is expressed in the basal layer of proliferating keratinocytes within the multilayered epithelia (Ramirez et al., 1994). Using the KRT5 minimal promoter fragment we derived transgenic mice wherein the above described apoptosis reporter was expressed in a tissue specific manner. Using KRT5 specific antibody as well as beta galactosidase specific antibody, we demonstrate here that the reporter was expressed within the basal layer of the epidermis and the outer root sheath of the hair follicles (Figure 4). The importance of this proliferating layer in UV-induced apoptosis was confirmed by immunostaining with an active caspase 3 specific antibody which showed localization to these cellular layers (Figure 6A) and that staining for active caspase 3 co-localized with cells wherein active LACZ activity was also present (Figure 6B). These results were further confirmed by western blot analysis of exvivo tissue samples wherein the ER-LACZ-ER reporter was expressed predominantly as an intact 190 kDa polypeptide in control animals, while significant cleavage of the reporter resulted in the 110 kDa active form of LACZ (Figure 5).

The sensitivity and specificity of the reporter was studied in cultured cells, and it was revealed that the reporter was able to detect levels of caspase 3 activity that were below what is required to induce phenotypic changes within cells. For example, as shown (Figure 2C, 2D), at 1 and 2.5 hr after TRAIL treatment, a major fraction of the cells appeared normal and lacked morphological features of apoptosis, but fluorescence imaging using lysed cells (Figure 2A) as well as live cells (Figure 2C) detected a significant change in LACZ activity. Similarly, at 25ng/ml of TRAIL (Figure 2B and 2D), morphologically the cells appeared normal, but significant LACZ activity was detected in cell extracts as well as in live cells.

The fact that this transgenic mouse model has expression of a sensitive and quantitative reporter within the crucial cellular populations of the skin that play a key role in the biology of the skin, suggests that this model will be invaluable for studies delineating the role of apoptosis in a variety of skin diseases as well as in the development and testing of therapeutic interventions for these diseases. Homeostasis between proliferation and apoptosis is crucial for optimal architecture of the skin and maintenance of epidermal barrier function. Although cornification of keratinocytes is morphologically indistinguishable from the morphological features observed in traditional programmed cell death (Lippens et al., 2009), it is interesting that in the transgenic mouse expressing the reporter for caspase 3 dependent apoptosis, no significant activation of the reporter was observed in non-stimulated skin. This observation is consistent with mounting evidence that caspase 3, 6, 7 and 9 may not be involved in epidermal differentiation leading to cornification (Lippens et al, 2009). Mice lacking these caspases have essentially normal skin development. In contrast, mice lacking caspase 14, a skin specific zymogen protease, has been implicated in skin development since mice lacking this protein have defective corneum formation (Denecker et al., 2007). Modification of the reporter described here so that it can be activated in a caspase 14 dependent manner would be a valuable tool in the study of skin morphogenesis.

In conclusion, mouse models provide many opportunities to improve our understanding of the basic biology and underlying molecular mechanisms involved in the dynamic processes associated with skin injury and repair. A key component of cellular response to stress is the activation of the apoptotic machinery. To this end, we have developed a transgenic mouse model wherein fluorescence activity of the skin was dependent on activation of caspase 3. Fluorescent activity following TRAIL treatment and UV radiation exposure was shown to be dose and time dependent and correlated with directly with caspase 3 activation. Temporal evaluation of caspase 3 activity was shown to be possible revealing the potential for using this molecular imaging reporter for a wide variety of studies for example, involving pre-treatment with UV-modifying agents. Overall, this study reports on the development and validation of a genetically engineered molecular imaging reporter construct for the detection of apoptosis in the skin of genetically engineered mice.

Methods

Construction of Hybrid Molecules

All methods in this paper were approved by the Medical Ethical Committee at the University of Michigan Briefly, two versions of the LACZ molecule were cloned into pEF vector. The first consisted of WT LACZ (pEFLacZ) and the second was chimeric fusion gene pEFERLACZER, which harbored sequences from estrogen receptor (residues 281-599 of the mouse estrogen receptor) at both the amino and the carboxy termini of the LACZ with the DEVD sequence intervening the two domains on either side. The coding sequences were cloned into the expression vector pEF, which drives transcription of the inserted coding sequence by using the Elongation Factor-1 alpha promoter with the neomycin-resistance gene as bicistronic message.

Cell culture, transfection and treatments

D54 (human glioma) cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 292 μg/ml L-glutamine (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA) and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. The constructs described above were transfected into D54 (human glioma) cells using Fugene (Roche Diagnostic Corporation, Indianapolis, IN), and the stable clones were selected using 0.2mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA) and characterized for expression of the reporter by western blot analysis using total cell lysates. Specific clones were identified and selected for further study based on expression levels of the recombinant protein. Purification of TRAIL was described elsewhere (Chinnaiyan et al., 2000). Treatments of cells with TRAIL were previously described in (Laxman et al., 2002). In vitro activation of caspase 3 in reporter expressing D54 cells was achieved by treating cells with 200ng/ml TRAIL.

In Vitro Activation of DDAOG

Reporter activation was measured by using the substrate 9H-(1,3-dichloro-9,9-dimethylacridin-2-one-7-yl) beta-D-galactopyranoside (DDAOG, Invitrogen) which upon cleavage produces a shifted far-red fluorescence (Tung et al., 2004). To measure cellular activation of DDAOG by beta galactosidase, D54, D54/LACZ, and D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells were seeded in 12-well plates at 75000/well and 175,000 cells/well for approximately for 16hr. Cells were washed 3X with HBSS and then treated with 100ng/ml of TRAIL. Following TRAIL treatment, DDAOG was added directly to the live cells at a final concentration of 10uM. After incubation, the fluorescence signal was measured using a FLUOstar OPTIMA fluorescent plate reader (BMG Labtech, Inc) with a 610 excitation filter and a 650 emission filter. By exciting at a wavelength greater than 600nm, only the cleaved substrate (DDAO) was excited and measured (Tung et al., 2004)

Fluorescence Imaging in vitro

Detailed cellular activation of DDAOG was monitored using a confocal microscope (Nikon D-Eclipse C1). D54, D54/LACZ, and D54/ER-LACZ-ER cells were grown on 25mm glass coverslips in 6-well plates to 80% confluency. First the cells were treated with TRAIL as specified and then incubated with DDAOG (10uM) for 30min @ 37 degrees in HBSS. Floating cells were collected and washed 3X with HBSS along with the coverslips. Confocal microscopy was performed with a Nikon D-Eclipse C1 3 Laser unit module (Spectra Physics, Argon 488, Green He-Ne 543, Red He-Ne 633). The argon 488 laser was used to visualize uncleaved DDAOG and the Red He-Ne 633 laser was used to visualize cleaved substrate.

Fluorescence imaging in vivo of D54/ER-LACZ-ER xenografts

Subcutaneous tumors expressing D54/ER-LACZ-ER were established by implanting 1 × 107 stably transfected cells subcutaneously on the dorsal surface of the skull in athymic nude mice (CD-1-Foxn1nu/Foxn1nu, Charles River Laboratory). Tumors were allowed to grow to 100 mm3 in size, at which point the experiment was initiated. Prior to imaging, animals were anesthetized using a mixed solution of ketamine (90mg/kg) and xylazine (10mg/kg) given via i.p. injection. The fluorescent substrate DDAOG (0.5mg) was then injected i.v. in a vehicle solution (100μl) comprising of DMSO and PBS (1:1), and fluorescence imaging was performed approximately 15–20 minutes after injection of substrate. Near infrared reflectance imaging was performed using the Maestro system (CRI, Woburn, MA) at 0hr and 12hr timepoints (Tung et al., 2004) in control and treated animals. The excitation and emission filters were set at 640nm and 700nm, respectively. The acquired images were then analyzed and quantified using the software package included in the CRI system. Signal levels were normalized based on background fluorescence levels on the skin by manually placing regions of interest. After normalization, the change in signal from each animal, using the same ROI for pre-treatment and treatment scans, was then calculated. All mouse experiments were approved by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA) of the University of Michigan.

PCR Amplification of the Transgene

The ER-LACZ-ER transgene was amplified using the Expand Long Template PCR kit (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland). The primer pair used for amplification was ERF (5’ AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCATGGGTGCTTCAGGAGAC) and ERR (3’ TTTTTTCCTTGCGGCCGCTCATCAGATCGTGTTGGGGAA). The 5.2kb product was purified using Qiagen PCR Purification Kit.

Transgenic Animals

All animals were cared for using protocols approved by the University Committee for the Use and Care of Animals. The pBK5 vector cassette containing the KRT5 promoter was kindly provided by the Dlugosz lab (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA). A Not1 PCR fragment containing the ER-LACZ-ER cDNA was inserted into the polylinker of the vector pBK5 that contained the 5.2-kb bovine KRT5 regulatory sequences, β globin intron 2 and the 3’ polyadenylation sequences. The ER-LACZ-ER transgene was excised from the pBK5ER-LACZ-ER cassette using Ase1. The transgene was purified and was used to generate transgenic animals at the Transgenic Animal Core (Van Andel Institute, Grand Rapids, MI) by microinjection of B6C3F2 oocytes. Transgenic ER-LACZ-ER expression was characterized using standard PCR techniques with primers specific for LACZ (5’LacZ, GCCTGCGATGTCGGTTTCCGCGAG and 3’LacZ, CGCGCGTACATCGGGC). A total of three distinct founder lines were obtained and inbred for five generations. To obtain a white background, all three founder lines were then crossed with FVB/N mice for at least three generations. All experiments were done using these animals that were inbred five generations followed by mating with FVB/N for at least three generations or more and were aged between 6–14 weeks.

Activation and measurement of apoptosis in vivo using UVB

1cm × 1cm patches on the dorsal skin of 2–6 week old mice were depilated using Nair. 24 hours later, the exposed dorsal skin patches were irradiated at a dose of approximately 600J/m2 using a UVB lamp (FS20T12-UVB, National Biological Corp, Twinsburg, OH), ensuring that no other portion of the mouse was exposed to radiation. According to the manufacturer, this UVB bulb emitted wavelengths between 250nm and 420nm, with peak emission at 313nm. The intensity of the UV light source was measured prior to each experiment using a UVX radiometer (UV Inc., Torrance, CA). The following day, mice were anesthetized, injected with DDAOG (0.5mg/kg) substrate 15–20 mins prior to imaging (details described above). Fluorescence activity was measured using the IVIS imaging system (Xenogen) at 0hr and 12hr timepoints. The excitation and emission filters were set at 610nm and 650nm, respectively. Fluorescence imaging was performed using the Living Image 3.0 software and images were acquired after a 2-min exposure. Signal background levels were measured by manually placing regions of interest (≤200 pixels) within the visible tumor margins and the adjacent skin.

Western Blot Analysis

Briefly, the mice were euthanized and protein extracts were prepared by homogenizing shaved skin in RIPA Buffer using a plastic homogenizer. 40μl of the crude extract was separated on Novex 4–20%Tris-Acetate SDS-PAGE gel (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked in 5% milk prepared in TBS-T and probed with beta galactosidase rabbit IgG fraction (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Rabbit anti actin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO). The secondary rabbit polyclonal antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was conjugated to HRP and the transgene was detected by chemiluminiscent HRP substrate.

Immunohistochemistry analysis and X-gal staining

Immunohistochemical staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded epidermis samples (prepared by University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center Tissue Core, MI) was performed using polyclonal rabbit anti mouse KRT5 (Covance Inc., CA) and anti beta galactosidase rabbit IgG fraction (Molecular Probes, CA). The reactions were visualized with goat anti-rabbit IgG labeled with Cy3 and Cy5. For active caspase 3 and X-gal immunostaining, cryosections of the skin tissue were prepared using a CryoJane and the tissue was stained using an active caspase 3 antibody and the beta galactosidase staining kit (Invitrogen). The samples were analyzed using a confocal microscope (Nikon).

Supplementary Material

The coding sequence as well as the corresponding translation of the ER-LACZ-ER reporter are shown. The first 975 basepairs code for the ER domain followed by the GGGDEVDGGG Caspase cleavage site. The beta galactosidase domain of the reporter is included from 978-4049 base pairs. The second caspase cleavage site intervenes the LACZ domain and the second ER domain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marina Grachtchouk (University of Michigan) and Bryn Eagleson (Van Andel Research Institute) for their support in this research. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health research grants R01CA129623 (AR), R21CA131859 (AR), U24CA083099 (BDR), P50CA093990 (BDR) and R01 AR045973 (AD)

Abbreviations

- ER

estrogen receptor

- DEVD

Asp-Glu-Val-Glu

- LACZ

beta galactosidase

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TRAIL

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha related apoptosis inducing ligand

- DDAOG

9H-{1,3-dichloro-9,9-dimethylacridin-2-one-7-yl} ß-D-galactopyranoside

- DDAO

7-hydroxy-9H-{1,3-dichloro-9,9-dimethylacridin-2-one

- KRT5

Keratin 5

- X-gal

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galadctopyranoside

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Afford S, Randhawa S. Apoptosis. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:55–63. doi: 10.1136/mp.53.2.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhojani MS, Rossu BD, Rehemtulla A. TRAIL and anti-tumor responses. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:S71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botchkareva NV, Ahluwalia G, Shander D. Apoptosis in the hair follicle. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:258–264. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brash DE. Cellular proofreading. Nat Med. 1996;2:525–526. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerroni L, Kerl H. Aberrant bcl-2 protein expression provides a possible mechanism of neoplastic cell growth in cutaneous basal-cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:398–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1994.tb00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnaiyan AM, Prasad U, Shankar S, Hamstra DA, Shanaiah M, Chenevert TL, et al. Combined effect of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand and ionizing radiation in breast cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1754–1759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030545097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denecker G, Hoste E, Gilbert B, Hochepied T, ovaere P, Lippens S, et al. Caspase-14 protects against epidermal UVB photodamage and water loss. Nat Cell Bio. 2007;9:666–74. doi: 10.1038/ncb1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanidi A, Harrington EA, Evan GI. Cooperative interaction between c-myc and bcl-2 proto-oncogenes. Nature. 1992;359:554–556. doi: 10.1038/359554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter-Lewensohn L, Hedblad MA, Wejde J, Larsson O. Immunohistochemical markers for distinguishing Spitz nevi from malignant melanomas. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:917–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann SH, Gores GJ. Apoptosis in cancer: cause and cure. Bioessays. 2000;22:1007–1017. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200011)22:11<1007::AID-BIES7>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G. The proto-oncogene Bcl-2 and its role in regulating apoptosis. Nat Med. 1997;3:614–620. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxman B, Hall DE, Bhojani MS, Hamstra DA, Chenevert TL, Ross BD, et al. Noninvasive real-time imaging of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16551–16555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252644499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Tron V, Ho V. Induction of squamous cell carcinoma in p53-deficient mice after ultraviolet irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:72–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippens S, Hoste E, Vandenabeele P, Agostinis P, DeClercq W. Cell death in the skin. Apoptosis. 2009;14:549–69. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0324-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loro L, Vintermyr OK, Johannessen AC. Apoptosis in normal and diseased oral tissues. Oral Dis. 2005;11:274–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Ducret CR, van de Rijn M, LeBrun DP, Smoller BR. bcl-2 expression in primary malignancies of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:909–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Apoptosis. Life and death decisions. Science. 2003;299:214–215. doi: 10.1126/science.1081274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris DA, Middleton MH, Whang K, Schleicher M, McGovern T, Bennion SD, et al. Human keratinocytes maintain reversible anti-apoptotic defenses in vivo and in vitro. Apoptosis. 1997;2:136–148. doi: 10.1023/a:1026456229688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincelli C, Haake AR, Benassi L, Grassilli E, Magnoni C, Ottani D, et al. Autocrine nerve growth factor protects human keratinocytes from apoptosis through its high affinity receptor (TRK): a role for BCL-2. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109:757–764. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj D, Brash DE, Grossman D. Keratinocyte apoptosis in epidermal development and disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:243–257. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez A, Bravo A, Jorcano JL, Vidal M. Sequences 5' of the bovine keratin 5 gene direct tissue- and cell-type-specific expression of a lacZ gene in the adult and during development. Differentiation. 1994;58:53–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1994.5810053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Villanueva J, Colome MI, Brisbay S, McDonnell TJ. The expression and localization of bcl-2 protein in normal skin and in non-melanoma skin cancers. Pathol Res Pract. 1995;191:391–398. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)80724-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. Apoptosome: the cellular engine for the activation of caspase-9. Structure. 2002;10:285–288. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00732-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A, O'Connor L, Dixit VM. Apoptosis signaling. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:217–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung CH, Zeng Q, Shah K, Kim DE, Schellingerhout D, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging of b-galactosidaseactivity using far red fluorescent switch. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1579–1583. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaar M, Eller MS, DiBenedetto P, Reenstra WR, Zhai S, McQuaid T, et al. The trk family of receptors mediates nerve growth factor and neurotrophin-3 effects in melanocytes. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1550–1562. doi: 10.1172/JCI117496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai S, Yaar M, Doyle SM, Gilchrest BA. Nerve growth factor rescues pigment cells from ultraviolet-induced apoptosis by upregulating BCL-2 levels. Exp Cell Res. 1996;224:335–343. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler A, Jonason AS, Leffell DJ, Simon JA, Sharma HW, Kimmelman J, et al. Sunburn and p53 in the onset of skin cancer. Nature. 1994;372:773–776. doi: 10.1038/372773a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The coding sequence as well as the corresponding translation of the ER-LACZ-ER reporter are shown. The first 975 basepairs code for the ER domain followed by the GGGDEVDGGG Caspase cleavage site. The beta galactosidase domain of the reporter is included from 978-4049 base pairs. The second caspase cleavage site intervenes the LACZ domain and the second ER domain.