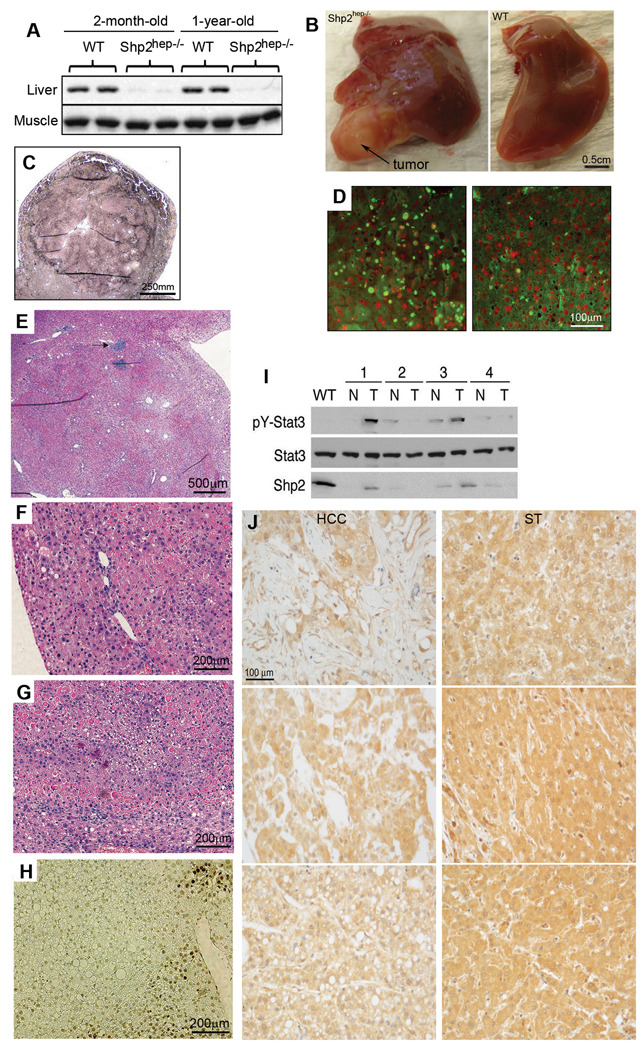

Figure 4. Spontaneous development of hepatocellular adenoma in aged Shp2hep−/− mice.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of Shp2 protein levels in the liver and muscle isolated from young or old WT and Shp2hep−/− mice.

(B) Macroscopic view of hepatic adenomas that bulged from the surface of Shp2hep−/− liver and appeared pale compared to the hepatic parenchyma.

(C) Reticulin staining of an adenoma.

(D) Hepatocyte proliferation in Shp2hep−/− (left panel) and WT (right panel) aged littermate mice. BrdU-positive cells were shown green, Dapi stained nuclei were red.

(E) H&E staining of an adenoma. Arrowhead points to a focal granuloma.

(F) H&E staining showed nodular regenerative hyperplasia.

(G) H&E staining showed hepatocyte degeneration, associated with vacuoles containing eosinophilic material at the periphery of adenoma.

(H) TUNEL assay revealed an area of focal apoptosis (dark brown nuclei) in the liver parenchyma. Slides were counterstained with methylgreen.

(I) pY-Stat3 levels in WT, tumoral Shp2hep−/− parenchyma (T) and non-tumoral (N) parenchyma of 18-month-old mice, as assessed by immunoblotting of tissue extracts.

(J) Human HCC specimens and corresponding surrounding tissue (ST) from the same patient were immunostained for Shp2. Shown here are 3 representative samples with Shp2 contents lower in HCC than in ST.

See also Figure S2.