Non-technical summary

Nerve fibres in the larynx detect foreign substances and elicit a stereotypical airway protective response that can be simulated by electrical stimulation of the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN). In humans the response includes cough, swallowing and a cessation of breathing (apnoea). It is still unknown precisely how the central nervous system coordinates swallowing and breathing, and at which point the two vital systems converge and diverge in the brain. Here we report a temporal, sequential relationship between excitation of expiratory laryngeal motoneurons that close the larynx during swallowing, and inhibition of breathing, during stimulation of the SLN in rat. The two phenomena can be dissociated by inactivating different brain areas. This work therefore has implications for diseases such as sudden infant death syndrome and Parkinson's disease, in which incoordination of breathing and protective behaviours may result in aspiration of irritants and subsequent death or aspiration pneumonia.

Abstract

Abstract

A striking effect of stimulating the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN) is its ability to inhibit central inspiratory activity (cause ‘phrenic apnoea’), but the mechanism underlying this inhibition remains unclear. Here we demonstrate, by stimulating the SLN at varying frequencies, that the evoked non-respiratory burst activity recorded from expiratory laryngeal motoneurons (ELMs) has an intimate temporal relationship with phrenic apnoea. During 1–5 Hz SLN stimulation, occasional absences of phrenic nerve discharge (PND) occurred such that every absent PND was preceded by an ELM burst activity. During 10–20 Hz SLN stimulation, more bursts were evoked together with more absent PNDs, leading eventually to phrenic apnoea. Interestingly, subsequent microinjections of isoguvacine (10 mm, 20–40 nl) into ipsilateral Bötzinger complex (BötC) and contralateral nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) significantly attenuated the apnoeic response but not the ELM burst activity. Our results suggest a bifurcating projection from NTS to both the caudal nucleus ambiguus and BötC, which mediates the closely related ELM burst and apnoeic response, respectively. We believe that such an intimate timing between laryngeal behaviour and breathing is crucial for the effective elaboration of the different airway protective behaviours elicited following SLN stimulation, including the laryngeal adductor reflex, swallowing and cough.

Introduction

The laryngeal chemoreflex, which is elicited by aspiration of fluid into the larynx, exerts a potent inhibition on breathing (Curran et al. 2005; Xia et al. 2007; Heman-Ackah et al. 2009). Dysfunction of this reflex is thought to underlie a number of life-threatening conditions, including sudden infant death syndrome (Pickens et al. 1988; Wetmore, 1993). Electrical stimulation of the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN) induces a potent and prolonged cessation of phrenic nerve discharge (PND) that can be abolished by intravenous injection of bicuculline (Barillot et al. 1984; Bellingham et al. 1989; Abu-Shaweesh et al. 2001; Bohm et al. 2007). During SLN stimulation-induced cessation of PND (phrenic apnoea), many inspiratory neurons are inhibited but expiratory neurons are either inhibited or tonically activated (Pantaleo & Corda, 1985; Bongianni et al. 1988; Czyzyk-Krzeska & Lawson, 1991). In cat, single pulse stimulation of the SLN, vagus or carotid sinus nerves during post-inspiratory (post-I) phase prolongs the depolarization of post-I neurons without changing their hyperpolarisation during late expiratory and inspiratory phases (Remmers et al. 1986). Despite these, and many other early studies, it is still unclear which neurons are crucial for the elaboration of the apnoeic response during stimulation of the SLN.

Most studies investigating activation of the SLN have been conducted in cat, with a much smaller number in rat. One reason for conducting the experiments outlined here in rat is because of the growing popularity of this species for investigating central neural circuitry in the control of breathing. The SLN contains afferent fibres whose peripheral endings are found in the laryngeal mucosa. The central fibres of laryngeal sensory neurons project to the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) (Bellingham & Lipski, 1992; Furusawa et al. 1996; Saito et al. 2002). Apart from eliciting apnoea, stimulation of the SLN also activates swallowing, cough and other airway protective reflexes; many of which are related to respiratory control (Kessler & Jean, 1985, 1986; Jean, 2001; Fontana & Lavorini, 2006; Kobashi et al. 2010). Clearly, the extent to which these different responses are elicited is species dependent: in human and cat, apnoea, swallow and cough are all prominent, whereas in rat apnoea and swallow predominates over cough. Moreover, in rat the expiration reflex (cough preceded by expiration) is present rather than cough preceded by inspiration which tends to occur in human (Korpas & Jakus 2000). For example, stimulation of the SLN at 10–30 Hz may induce fictive swallowing, accompanied with a strong respiratory depression (Ezure et al. 1993; Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000). On the other hand, stimulation of the SLN at 2–5 Hz may induce fictive coughing, accompanied with strong activation of all respiratory neurons recorded (Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000; Shiba et al. 2007). It is not clear how stimulation of the same afferent nerve with different frequencies produces such qualitatively different responses from respiratory neurons.

Expiratory laryngeal motoneurons (ELMs) are located in the caudal nucleus ambiguus and fire with a post-I pattern (Berkowitz et al. 2005; Ono et al. 2006; Sun et al. 2008). SLN stimulation activates the ELMs that control laryngeal constrictor muscles during phrenic apnoea and many other airway protective reflexes (Davis & Nail, 1984; Czyzyk-Krzeska & Lawson, 1991; Jiang & Lipski, 1992; Yoshida et al. 1998; Jean, 2001; Ludlow, 2005). The activation of ELMs during phrenic apnoea following SLN stimulation occurs in bursts. Both ELM burst activity and phrenic apnoea are elicited by the same stimulation of the SLN (Barillot et al. 1984), but the mechanism remains unclear. Thus, in the present study, we aimed to test (1) if there is a temporal, sequential relationship between the two responses, and (2) under what circumstances the two phenomena can be dissociated from each other. Based on previous studies (Oku et al. 1994; Saito et al. 2003), we hypothesised that the phrenic inhibition is likely to be produced by neurons in the Bötzinger complex (BötC) that are activated in the same way as the ELM during stimulation of the SLN.

Methods

This study was approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Macquarie University. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals as endorsed by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/ea16syn.htm). All experiments also conformed to the standards required by The Journal of Physiology (Drummond, 2009).

Animal preparation

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (350–500 g; n = 14) were anaesthetised with sodium pentobarbitone (72 mg kg−1i.p.). Atropine (0.4 mg kg−1, i.p.) was injected in order to reduce bronchial secretions. The level of anaesthesia was checked every 30 min by monitoring blood pressure and PND in response to a nociceptive stimulus (paw pinch or tail pinch). Administration of additional doses of sodium pentobarbitone (3 mg kg−1, i.v.) were given when increases in blood pressure or change in breathing pattern occurred. The right femoral artery and vein were cannulated for measurement of arterial blood pressure and drug administration, respectively. The left phrenic nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) and SLN were prepared for stimulation or recording from their central end with standard bipolar electrodes (Fig. 1, Pilowsky et al. 1990). The left facial nerve was also exposed for stimulation. Rats were mounted in a stereotaxic frame, artificially ventilated (frequency 75–80 cycles min−1, volume 3.0–4.5 ml) with oxygen-enriched air via a tracheostomy, and subjected to neuromuscular blockade with pancuronium bromide (1.6 mg kg−1, i.v. with extra doses of 0.8 mg kg−1 as needed). The medulla and upper spinal cord (C3–8) were exposed by occipital craniotomy and cervical laminectomy. Body temperature (36–37°C), expired CO2 (4–5%) and mean arterial blood pressure (80–120 mmHg) were monitored and maintained in the normal range.

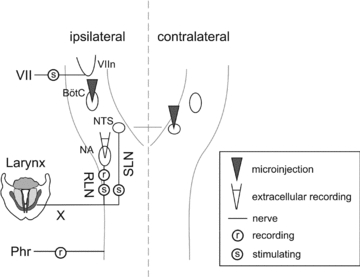

Figure 1. Summary of experimental procedures from the dorsal view of the medulla and spinal cord.

During single unit experiments, laryngeal motoneurons in the nucleus ambiguus (NA) were recorded extracellularly during stimulation of the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN). Expiratory laryngeal motoneurons in the NA were identified by antidromic stimulation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). Both the RLN and SLN are branches of the vagus nerve (X), which was therefore left intact. Recording of electrical discharge in the phrenic nerve (Phr) served as a measure of the neural drive to breathe. During microinjection experiments, the ‘burst activity’ of expiratory laryngeal motoneurons during SLN stimulation was monitored by recording the RLN. The GABAA agonist isoguvacine was microinjected into the ipsilateral Bötzinger complex (BötC) and/or the contralateral interstitial subnucleus of the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) during the experiments. The BötC nucleus was located 0–500 μm from the caudal end of the facial motor nucleus (VIIn), which was mapped by antidromic stimulation of the facial nerve (VII).

Recording and stimulation

The caudal nucleus ambiguus was localised by recording field potentials that follow stimulation of the RLN, using glass microelectrodes filled with 3 m NaCl (resistance 5–10 MΩ). Sites to record from ELMs were chosen from sites where field potentials were maximal. Stimulation intensity of the RLN was set at 5–10 V with 0.2 ms duration. Apnoeic threshold was determined following stimulation of the SLN (20 Hz, 0.2 ms), with an increasing voltage until PNDs stopped within three respiratory cycles during the stimulation. Location of the facial nucleus was mapped by recording the antidromic field potential from electrical stimulation of the facial nerve (Pilowsky et al. 1990; Sun et al. 1997). The BötC was then searched for within 500 μm of the end of the facial nucleus. PND was rectified and smoothed (weighted average 50 ms) before its size was calculated by measuring the area under the curve of the rectified PND. At the end of each electrophysiological experiment, rats were killed by injection of 3 m KCl (0.5 ml, i.v.).

Microinjection

Pressure microinjections of the GABAA receptor agonist isoguvacine (10 mm, 20–40 nl, Sigma) with pontamine sky blue (∼2%, Sigma) were made from standard glass micropipette (1.0 mm × 0.25 mm, SDR) with tip diameters of 20–40 μm in four rats (Fig. 1). Effective injection sites were found: for the BötC injection, around 0.5 mm caudal from the caudal end of the facial nucleus, 2 mm lateral from the midline, and 3 mm deep from the dorsal surface; for the NTS injection, around 0.1 mm caudal from obex, 0.5 mm lateral from the midline and 0.5 mm deep from the dorsal surface. Effects of isoguvacine microinjections were recorded from the RLN and phrenic nerve 2 min after each microinjection. At the end of each microinjection experiment, rats were perfused transcardially with 200 ml of saline, followed by 500 ml of 4% formaldehyde in distilled water. The brainstem was post-fixed overnight and cut into 100 μm transverse sections before visualizing the injection sites under a microscope.

Data analysis

Spikes were confirmed to be derived from single units using Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) to demonstrate that a spike consistently had the same shape, and interval time histograms were generated to demonstrate the presence of a refractory period (5 ± 3 ms). Only single units were studied here. Burst activity in the ELMs was analysed off-line using Spike2 software to measure their number, duration and mean firing frequency using the ‘burst’ script supplied with the software. A ‘burst index’ was obtained by multiplication of the burst duration and the mean firing frequency during the burst. Bursts were summed for each SLN stimulation period. Data are presented as means ± SD (standard deviation). Student's t test, or analysis of variance (ANOVA), was used to compare two or more variables, respectively. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis of data.

Results

In ten rats, extracellular recordings were made from 15 ELMs located within 1.5 mm from the obex caudally, 1.7–2.1 mm lateral from the midline, and 1.8–2.3 mm deep from the dorsal surface of the medulla. They were identified by antidromic response to stimulation of the RLN with a response latency of 2.2 ± 0.3 ms and a post-I firing pattern (Fig. 2). Neurons were considered to be antidromically activated if they (1) demonstrated a constant latency following stimulation of the RLN and (2) collided with orthodromic spikes that occurred within the refractory period (Fig. 2B, Sun et al. 2005). Neurons were considered to be orthodromically activated by the SLN if a constant latency was not present and collisions were not observed (Fig. 2C). Since the vagus nerve was intact, PND tended to be entrained to the frequency of artificial ventilation in a 1:1 phase-locked manner. Tetanic stimulation of the SLN at different frequencies (1–20 Hz) at 1.5 times the apnoeic threshold (2–5 V) for 10 s was used, and applied at random in relation to the respiratory phase.

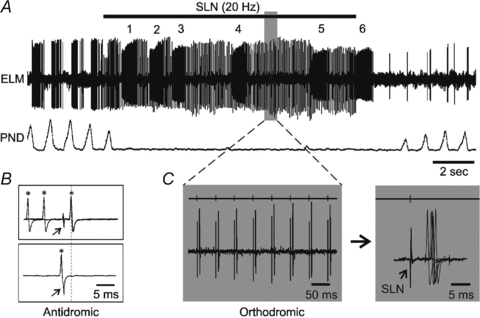

Figure 2. Effect of 20 Hz stimulation of the superior laryngeal nerve (SLN).

A, extracellular recording of an expiratory laryngeal motoneuron (ELM) and phrenic nerve discharge (PND) neurogram. The ELM response includes at least two components: one is burst activity numbered 1–6; the other is orthodromic action potentials. B, antidromic response of the ELM to stimulation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). The arrow indicates the stimulus artefacts. Asterisks indicate the ELM action potentials. In the top trace, spontaneous spikes that arrive more than 2.3 ms before the stimuli do not collide with the antidromic responses. However, a spontaneous spike in the bottom trace that arrives just before the stimulus (partly overlapped) collides with the antidromic responses (dotted line). C, expansion of orthodromic response in the shaded area from A. The right panels show the first six orthodromic action potentials from the left on a longer time base, with point of stimulation of the SLN indicated above the trace (arrow in the panel on the far right).

20 Hz SLN stimulation

Unilateral stimulation of the SLN (20 Hz) caused a cessation in PND (Fig. 2A). Total PND was reduced during SLN stimulation to 9 ± 8% of baseline, as measured from PND for 10 s prior to stimulation. There was no post-I activity evident in the ELM recordings after the PND inhibition that occurred during stimulation of the SLN. Instead, ELMs responded to SLN stimulation with a robust tonic firing that, upon closer inspection, consisted of at least two different components. One component consisted of orthodromic action potentials (Fig. 2C) that occurred following 89 ± 15% of the SLN stimuli with an averaged response latency of 6.1 ± 0.7 ms. The other component consisted of bursts of activity (burst activity) with a firing frequency and duration of over 40 Hz and 200 ms, respectively. Of the 15 ELMs, the average number of bursts evoked during SLN stimulation was 7.9 ± 2.2, with a duration of 365 ± 136 ms, and a mean frequency of 96 ± 45 Hz.

10 Hz SLN stimulation

During 10 Hz SLN stimulation, total PND was reduced to 29 ± 13% of baseline, although complete cessation of PND was not seen (Fig. 3A). Post-I activity was occasionally observed following most but not every remaining PND. ELMs exhibited orthodromic action potentials following 73 ± 27% of SLN stimuli. The bursts were easily discriminated from the post-I activity by their robust firing; in many cases there was a visible gap of up to 100 ms between the post-I and burst (Fig. 3A). The average number of bursts was 6.1 ± 1.2, with a duration of 314 ± 103 ms, and a mean frequency of 101 ± 49 Hz (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Effect of lower frequency stimulation of the SLN.

A, responses of PND and an ELM to 10 Hz SLN stimulation. Note that, apart from the bursts (numbered 1–6) and orthodromic responses during SLN stimulation, the ELM is also occasionally active during the post-inspiratory (post-I) phase as marked by the black dots underneath. Stimulation artefacts of the SLN are drawn in grey for both A and B. The panels below expand the two shaded areas, showing a clear separation of about 60 ms between the post-I and burst activity on the left and the orthodromic response on the right, respectively. B, responses of PND and an ELM to 5 Hz SLN stimulation. The arrow indicates the absence of one PND that is preceded by a burst of ELM activity (asterisk).

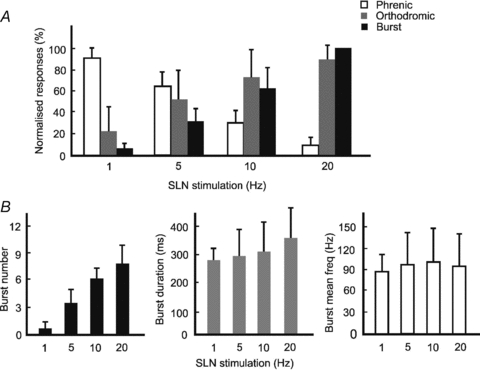

Figure 4. Effects of SLN stimulation at different frequencies.

A, bar graph of the normalized ELM response and PND during 1–20 Hz SLN stimulation (mean ± SD). The open bars show the total PND during stimulation of the SLN, normalized to 10 s of PND before SLN stimulation. The grey bars show the occurrence rate of orthodromic responses of the ELM as a percentage of total SLN stimuli. The black bars show the ELM burst activity, normalized to burst activity during 20 Hz SLN stimulation. B, bar graphs of the ELM burst activity during SLN stimulation, showing changes of their number, duration and mean firing frequency.

1–5 Hz SLN stimulation

During lower frequency SLN stimulation (1 and 5 Hz), most PND remained, with only one, or a few absences occurring (Fig. 3B). A clear pattern started to emerge: every absence in PND was preceded by an ELM burst. However, the opposite was not always true; not every ELM burst was followed by a PND absence. Total PND during 1 and 5 Hz SLN stimulation was measured as 92 ± 8% and 64 ± 14% of baseline, respectively. Post-I firing was present as regularly as the preserved PND (Fig. 3B). Fewer action potentials were orthodromically activated during 1 and 5 Hz SLN stimulation, with an occurrence rate of 22 ± 24% and 52 ± 31%, respectively. In about one-third of the cases (22/65), the burst was aligned with a small extra PND (Fig. 3A). In addition, there were seven bursts that were preceded by an enlarged PND (over 10% in size, Fig. 3B). During 1 Hz SLN stimulation the average number of bursts was 0.6 ± 0.7, with a duration of 276 ± 77 ms, and a mean frequency of 85 ± 33 Hz. During 5 Hz stimulation these were 3.5 ± 1.6 bursts, 294 ± 96 ms and 97 ± 43 Hz, respectively (Fig. 4).

To summarize, as SLN stimulation frequency increased, total PND was significantly reduced (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A). In contrast, burst activity recorded from the ELM was significantly increased (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A). ELM burst activity was calculated by multiplying duration by mean firing frequency. Total ELM burst activity at 1, 5 and 10 Hz of the SLN stimulation was then normalized to the amount of burst activity at 20 Hz. The calculated values of normalised activity using this approach were: 4 ± 5% (1 Hz), 30 ± 13% (5 Hz), 63 ± 20% (10 Hz) and 100% (20 Hz), respectively (Fig. 4A). The increased amount of burst activity was mainly due to increases in the number and duration, rather than mean frequency, of each burst (Fig. 4B). The appearance of orthodromic responses increased steadily as SLN stimulation frequency increased (Fig. 4A).

Burst activity and absence of PND

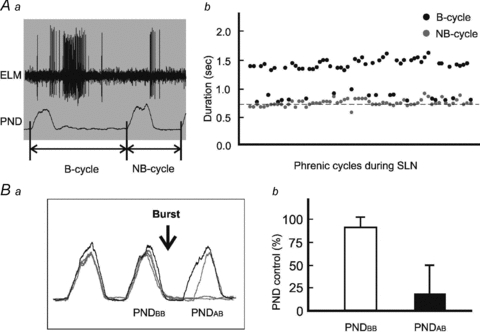

The observation that absence of PND was always preceded by ELM burst activity was studied further following 1 or 5 Hz SLN stimulation. At these lower frequencies of SLN stimulation, phrenic cycles, measured as the duration between the onset of two consecutive PNDs, were divided into ‘burst’ or ‘non-burst’ cycles, depending on the presence or absence of an ELM burst (Fig. 5A). All non-burst cycles (n = 65) immediately preceding the burst cycles had a duration of less than 930 ms (Fig. 5A), with an average duration of 776 ± 60 ms. This corresponded with a ventilation cycle of 75–80 cycles min−1, to which the phrenic cycle was phase-locked. In contrast, the majority of burst cycles (47/65; 72%) ranged between 1300 and 1600 ms (Fig. 5A), with an average duration of 1442 ± 73 ms. Such a length was roughly twice the length of a non-burst cycle and corresponded with a ‘quantal’ miss of a PND. We also compared the size of individual PNDs between those immediately before the burst (PNDBB) and those immediately after the burst (PNDAB) during SLN stimulation (Fig. 5B). In comparison to the control, which was measured as the average size of three PNDs prior to SLN stimulation, the PNDBB was slightly, but significantly, reduced, with an average size of 92 ± 2% in comparison to control (P < 0.05, Fig. 5B). In contrast, the PNDAB was significantly reduced with greater than fourfold (21 ± 4%) reduction in size compared with PNDBB (P < 0.05, Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Relationship between ELM burst and PND absence.

Aa, two types of phrenic cycles. One is a cycle during which the ELM fires with a burst activity (B). The other is a cycle during which no burst activity (NB) is observed. Ab, black dots represent lengths of every B cycle during 1 and 5 Hz SLN stimulation, and grey dots lengths of those NB cycles that are present immediately before the B-cycles. The dashed baseline indicates the cycle length of ventilation at a frequency of 80 cycles min−1. Note that 47/65 B-cycles occur at about twice as long as baseline. Ba, an overlay of five raw traces of rectified PNDs, including one before (black) and four during (grey) stimulation of the SLN. PNDBB is the PND immediately before the burst, and PNDAB is the PND immediately after the burst. The arrow indicates the position of the burst. Bb, open and filled bars represent the sizes of PNDBB and PNDAB respectively, which are normalized to control, as measured from an average of three consecutive PNDs before stimulation of the SLN.

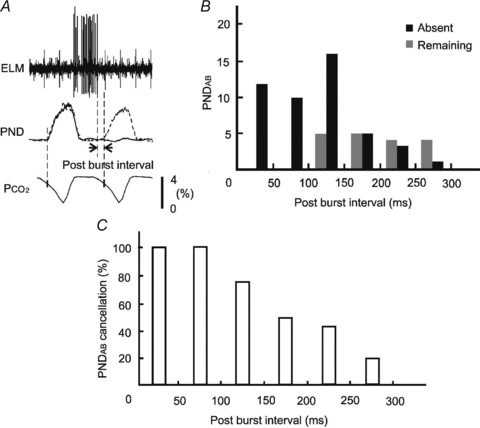

The timing of an ELM burst in relation to the absence of PND was examined by measuring the “post-burst interval’ which we defined as the length of time between the end of each ELM burst and the onset of the PNDAB. In situations where there was an absence of PNDAB, the expected onset of PNDAB was determined from the average duration of three phrenic cycles and onset of the PND in relation to the ventilation cycle before the SLN stimulation (Fig. 6A). When the post-burst interval was less than 150 ms, about 90% of the expected PNDAB (38/43) were absent (Fig. 6B). The five exceptions included three PNDAB, where the size was reduced by more than 40% compared with control PND. When the interval was between 150 and 250 ms, about 50% of PNDAB (8/17) were absent. At intervals of 250 ms or longer, there was only one absence of PNDAB. The absence rate of PNDAB was calculated from the percentage of absent PNDAB out of the total PNDAB under different post-burst intervals (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. Post-burst interval and absent PNDAB.

A, the post-burst interval is defined as the duration between the end of an ELM burst and the onset of the next PNDAB. The latter is determined, when the PNDAB is absent, from the average duration of three phrenic cycles and onset of the PND in relation to the ventilation cycle before stimulation of the SLN. B, histograms of PNDAB absence in relation to the post-burst interval. Black and grey bars represent the numbers of absent and remaining PNDAB, respectively, within different post-burst intervals. C, absence rate of the PNDAB under different post-burst interval. The absence rate is calculated by expressing the number of absent PNDAB as a percentage of the total expected PNDAB at binned intervals.

Isoguvacine microinjection

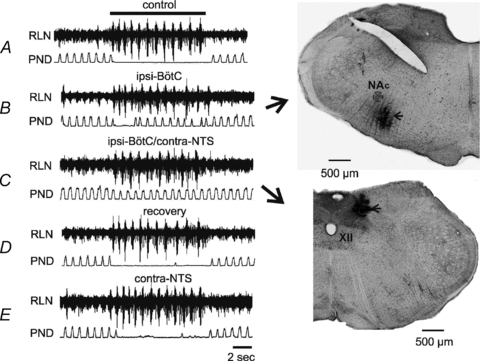

Microinjections of the GABAA receptor agonist isoguvacine (10 mm, 20–40 nl) were made in four rats, in which the RLN was recorded to monitor the ELM burst activity (Lucier et al. 1978). Before microinjection, 20 Hz stimulation of the SLN caused an apnoeic response as described above, with total PND reduced to 12 ± 9% of baseline (Fig. 7A). A microinjection of isoguvacine into the ipsilateral BötC significantly weakened the apnoeic response (Fig. 7B), with total PND during the SLN stimulation increased approximately fourfold from 12 ± 9% to 44 ± 13% of baseline (P < 0.05). After a further microinjection of isoguvacine into the contralateral NTS, no PND absence was seen during the SLN stimulation, with total PND measured at 74 ± 6% of baseline (Fig. 7C). In contrast, neither the BötC nor NTS inactivation had an obvious effect on burst activity monitored from the RLN (Fig. 7A–C). The injection sites were marked by pontamine sky blue at the same time as the microinjection (Fig. 7B and C). In two out of the four rats, after a 60 min of recovery (Fig. 7D), a repeat microinjection of isoguvacine into the contralateral NTS, without a preceding BötC microinjection, had little effect on the apnoeic response (Fig. 7E).

Figure 7. Representative traces of the effect of microinjections of isoguvacine (10 mm, 20–40 nl) on PND and ELM burst activity monitored from the RLN during 20 Hz SLN stimulation.

A, responses of phrenic nerve and RLN to stimulation of the SLN before any microinjection. The top bar indicates duration of the SLN stimulation for each of the following traces. B, effect of a microinjection of isoguvacine into the ipsilateral Bötzinger complex (BötC). Note that the SLN induced phrenic apnoea was strongly attenuated. The injection sites were marked by pontamine sky blue (indicated by arrows) at the same time of the microinjection (B-C, NAc: compact formation of the nucleus ambiguous, XII: the hypoglossal nucleus). C, effect of a subsequent microinjection of isoguvacine into the contralateral nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS), leading to no PND absence during the SLN stimulation. In contrast, neither the BötC nor NTS microinjection has a visible effect on burst activity monitored from the RLN (B-C). D, recovery of the apnoeic response after 60 min of the NTS microinjection. E, microinjection of isoguvacine into the contralateral NTS, without the BötC microinjection, has little effect on the apnoeic response.

Discussion

The major novel finding of this study is that activation of ELMs and cessation of PND following stimulation of the SLN are due to two mechanisms that become separate beyond the level of the NTS. Our study is not the first to correlate ELM excitation with phrenic apnoea. According to Barillot et al. (1984), single pulse stimulation of the SLN at 5 times apnoeic threshold in the cat produces a large EPSP from ELMs and PND is silenced during the EPSP. However, our study is the first to demonstrate that ELM burst-related PND absences are tightly coupled with the apnoea that follows SLN stimulation, a phenomenon that becomes clearer as the stimulus frequency is decreased. Interestingly, we find that it is possible to almost entirely abrogate the apnoeic response without affecting the burst activity, by microinjection of isoguvacine into the ipsilateral BötC and contralateral NTS. Our results support the idea that the generation of ELM bursts and the development of phrenic apnoea are the result of activation of the same antecedent neuronal circuitry within the NTS following SLN stimulation.

The ELM burst and PND absence

Several earlier studies have investigated the burst activity from ELMs and other neurons during activation of different airway protective reflexes following SLN stimulation (Ezure et al. 1993; Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000; Jean, 2001; Saito et al. 2003; Fontana & Lavorini, 2006). However, the finding in our study that individual ELM bursts are correlated with PND absence is not well documented. One difference between our study and others may relate to differences in species. In larger animals, such as cat, PND occurs at a much lower frequency than 70–80 cycles min−1, as reported here (Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000). In the context of the critical post-burst interval (Fig. 6), it is not surprising to see that there are fewer PND absences during low frequency SLN stimulation (Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000). This is because, for many evoked bursts, the longer respiratory cycle length delays the next PND with its onset far behind the effective period of the post-burst interval, and is therefore unlikely to be affected by the burst related inhibition (Fig. 6). The dissociation between the burst and PND absence in larger animals may only be evident during low frequency stimulation of the SLN. When there are sufficiently large numbers of the bursts evoked during higher frequency stimulation of the SLN (Fig. 2), the burst related inhibition may become amalgamated and produce a strong phrenic apnoea regardless of respiratory cycle length. This means that the gradual development of PND apnoea following SLN stimulation is more clearly seen in rat where PND occurs frequently (i.e. short phrenic cycle). In larger species, PND occurs less frequently (i.e. longer phrenic cycle) so that the development of apnoea with SLN stimulation appears to be rather sudden.

Our study also differs from earlier studies in the way that we analysed individual PND in relation to the ELM bursts during SLN stimulation. In agreement with previous studies that the SLN stimulation may evoke burst activity involved in different reflexes (Ezure et al. 1993; Jean, 2001; Fontana & Lavorini, 2006), we found during SLN stimulation (1.5 times apnoeic threshold, 1–5 Hz) that about one-third of the bursts were aligned with an extra small discharge of the phrenic nerve that may correspond to ‘swallow-breath’ in cat (Oku et al. 1994). Approximately 10% of bursts were preceded by a relatively larger PND that may correspond to expiration or other reflexes (Korpas & Jakus, 2000). However, we did not attempt to catalogue these separately, since all bursts appeared to show a similar relationship with individual PND absences (Figs 5 and 6). It should be noted that this homogeneous effect of the ELM burst on the PND absence is not necessarily controversial with respect to the previously reported heterogeneous effects on PND (Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000; Shiba et al. 2007). The reason for this is that we find that the burst discharge in ELMs is associated with inhibition of PND immediately after the burst (Figs 5 and 6), whereas previous investigators did not clearly differentiate whether a burst preceded, or succeeded, PND apnoea (Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000; Shiba et al. 2007). Since networks of NTS neurons are essential for the elaboration for many different reflexes (Jean, 2001; Fontana & Lavorini, 2006), there may exist a common mechanism in the NTS for the generation of burst activity to stop central inspiration in order to avoid aspiration of any unwanted substances into the trachea (Bolser et al. 2006).

Technical limitations

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. First, we stimulated the SLN at different frequencies (1, 5, 10 and 20 Hz) to study the development of inhibition of PND, from a few PND absences, to complete ‘PND apnoea’. Although this method of stimulation is not the same as the naturalistic approach used by others it does evoke an almost identical stereotypic response with a reduction of PND (Curran et al. 2005; Bohm et al. 2007; Xia et al. 2007). It remains to be determined how the SLN afferent neurons in the nodose ganglion react to different naturalistic stimuli applied to the laryngeal mucosa, by changing their firing frequencies or other parameters; such questions were not the object of the present study. Secondly, in the present study we did not record from hypoglossal and expiratory lumbar nerves so as to further characterize ELM behaviours that are elicited by SLN stimulation. Future studies that incorporate such recordings will assist in further defining the swallowing nature of the bursts reported here. Nevertheless, we believe that it is reasonable to speculate that the bursts reported here are indeed associated with swallowing since this is the main physiological response, apart from apnoea, associated with the activation of the laryngeal mucosal nociceptors.

Inhibition related to the ELM burst

Although the burst activity is closely related to the absence of PND, ELMs project directly to laryngeal constrictor muscles and do not have intramedullary axon collaterals (Davis & Nail, 1984; Yoshida et al. 1998; Berkowitz et al. 2005; Ludlow, 2005; Sun et al. 2008). In other words, they are therefore unable to activate inhibitory interneurons and stop inspiration. Given the intimate association between the two, the simplest possibility is that the same synaptic drive that produces the ELM burst may also simultaneously project to neurons that inhibit central inspiration, so that the ELM burst is tightly correlated to the apnoeic response.

According to previous studies many inspiratory neurons are inhibited, but expiratory neurons are either inhibited or tonically activated, during SLN stimulation (Pantaleo & Corda, 1985; Czyzyk-Krzeska & Lawson, 1991; Bongianni et al. 2000). However, the tonic activity is likely to result from a removal of inhibitory inspiratory activity (disinhibition), rather than a direct excitatory connection from SLN afferent neurons via the NTS (Bongianni et al. 1988). On the other hand, during fictive swallowing induced by SLN stimulation, complex behaviours are elicited from BötC neurons. For example, many decrementing expiratory neurons from BötC are found to be active during ‘swallowing burst’ (Oku et al. 1994; Saito et al. 2003). There are also decrementing BötC expiratory neurons that are activated immediately after the swallowing burst with a short-lasting firing activity (Saito et al. 2003). In addition, some BötC augmenting expiratory neurons are found to be silent but fire actively between the swallowing bursts (Oku et al. 1994; Saito et al. 2003). Since many BötC neurons are known to have widespread inhibitory connections with other respiratory neurons including respiratory rhythm generating neurons in the pre-BötC (Ezure, 1990; Smith et al. 1991; Bryant et al. 1993; Tan et al. 2008), they are ideal candidates to be the inhibitory neurons responsible for producing PND absence during and after ELM bursts during stimulation of the SLN (Fig. 6).

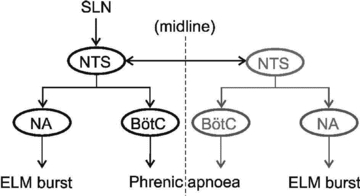

A possible role for the BötC in the apnoeic response was examined using microinjection of isoguvacine to inactivate neurons located in the ipsilateral BötC and contralateral NTS. An initial microinjection of isoguvacine into the ipsilateral BötC significantly weakened the apnoeic response (Fig. 7B), providing evidence for BötC involvement in this response. It is well known that the burst activity, such as bursting related to swallowing, is synchronized bilaterally in the NTS (Doty et al. 1967; Jean, 2001). Accordingly, during the SLN stimulation, the contralateral BötC neurons may also be activated as a result of such synchronization (Fig. 8). If this were the case, we should see a further blockade of the apnoeic response after inactivating contralateral NTS neurons and thus presumably the downstream contralateral BötC neurons. After a subsequent isoguvacine microinjection into the contralateral NTS, no PND absence was seen during the SLN stimulation (Fig. 7C). Accordingly, BötC neurons are not only activated during the SLN stimulation induced swallowing (Oku et al. 1994; Saito et al. 2003), but also play a critical role during the SLN induced apnoea.

Figure 8. A proposed neuronal pathway for control of the SLN induced apnoea, in which nuclei on the ipsilateral side of the SLN stimulation are marked in black, and nuclei on the contralateral side of the SLN stimulation are marked in grey.

Note that stimulation of either SLN is able to cause a burst in ELMs and apnoea. The data suggest that it is the excitatory pathway from NTS to nucleus ambiguus that causes the burst firing in ELMs, whilst the phrenic apnoea is caused by activation of the inhibitory Bötzinger neurons.

Dissociation between the ELM burst and PND absence

The present study not only demonstrates that the PND absences are closely associated with the ELM burst activity, but also that the two phenomena can be dissociated from each other by microinjection of isoguvacine into the ipsilateral BötC and contralateral NTS. Here, ELM burst activity was monitored by recording from the RLN in order to avoid the difficulty of holding single unit recordings from ELMs during and after microinjections. Although the RLN contains descending axons from both inspiratory and expiratory laryngeal motoneurons (Sun et al. 2005; Bautista et al. 2010), only ELMs are activated during the SLN induced apnoea (Lucier et al. 1978). One potential application for our findings is that they may help to explain a spectrum of symptoms that are observed clinically during laryngeal stimulation such as apnoea and laryngospasm (Ikari & Sasaki, 1980; Thach, 2008).

Burst and post-I activity of the ELMs

An unresolved question is whether or not the ELM burst activity evoked during the SLN stimulation is a modified post-I activity that originates from the same neuronal networks that generate respiration, or from an entirely different non-respiratory origin (Oku et al. 1994; Gestreau et al. 2000). Here we report that, during low frequency SLN stimulation, the burst activity can be identified separately from the post-I activity with a gap of up to 100 ms (Fig. 3). The separation is likely to correspond with the same strong hyperpolarization preceding the ELM bursts observed during intracellular studies of fictive swallowing and other airway protective reflexes (Gestreau et al. 2000). This hyperpolarization is produced by a monosynaptic inhibition from BötC expiratory-augmenting neurons (Shiba et al. 2007). However, we are reluctant to regard the ELM burst activity as an enhanced post-I. According to Oku et al. (1994), the burst activity related to swallowing is not post-I activity, because it is only found during swallowing. In the present study, we also found differences between the two in their responses to graded SLN stimulation. When PND is reduced by increasing the SLN stimulation frequency (1–20 Hz), the ELM burst number and duration are increased. In contrast, there is little post-I activity during high-frequency stimulation, and rather regular post-I activity found during low-frequency stimulation of the SLN.

We believe that the findings reported here provide new insight into the way that the laryngeal chemoreflex is co-ordinated following activation of sensory afferent neurons in the SLN that innervates the subglottic mucosa. The data indicate the manner in which bursts of activity in ELMs, which are responsible for laryngeal adduction and, we believe, are likely to be associated with swallowing, are coordinated with cessation of phrenic discharge in order to prevent inappropriate aspiration into the lungs. Moreover, the data demonstrate that the neural pathways involved in coordinating these responses within the brainstem diverge at the level of the NTS.

Acknowledgments

All work performed at Australian School of Advanced Medicine was supported by grants from the Garnett Passe and Rodney Williams Memorial Foundation, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (457069, 457080, 604002), the Australian Research Council (DP110102110) and Macquarie University. T.G.B. is in receipt of a Macquarie University Research Excellence scholarship.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BötC

Bötzinger complex

- ELM

expiratory laryngeal motoneuron

- PND

phrenic nerve discharge

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarii

- post-I

post-inspiratory

- RLN

recurrent laryngeal nerve

- SLN

superior laryngeal nerve

Author contributions

Q.-J.S.: conception and design of the experiments, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article. T.G.B.: conception of experiments, collection and interpretation of data, and critical revision of article. R.G.B.: conception and design of the experiments. W.-J.Z.: collection of data; P.M.P.: conception, design and analysis of the experiments, and revising critically for important intellectual content. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors.

References

- Abu-Shaweesh JM, Dreshaj IA, Haxhiu MA, Martin RJ. Central GABAergic mechanisms are involved in apnea induced by SLN stimulation in piglets. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1570–1576. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.4.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barillot JC, Bianchi AL, Gogan P. Laryngeal respiratory motoneurones: morphology and electrophysiological evidence of separate sites for excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs. Neurosci Lett. 1984;47:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista TG, Sun QJ, Zhao WJ, Pilowsky PM. Cholinergic inputs to laryngeal motoneurons functionally identified in vivo in rat: A combined electrophysiological and microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:4903–4916. doi: 10.1002/cne.22495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellingham MC, Lipski J. Morphology and electrophysiology of superior laryngeal nerve afferents and postsynaptic neurons in the medulla oblongata of the cat. Neuroscience. 1992;48:205–216. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellingham MC, Lipski J, Voss MD. Synaptic inhibition of phrenic motoneurones evoked by stimulation of the superior laryngeal nerve. Brain Res. 1989;486:391–395. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90530-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz RG, Sun QJ, Goodchild AK, Pilowsky PM. Serotonin inputs to laryngeal constrictor motoneurons in the rat. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:105–109. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000150695.15883.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm I, Xia L, Leiter JC, Bartlett D. GABAergic processes mediate thermal prolongation of the laryngeal reflex apnea in decerebrate piglets. Resp Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;156:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser DC, Poliacek I, Jakus J, Fuller DD, Davenport PW. Neurogenesis of cough, other airway defensive behaviors and breathing: A holarchical system? Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;152:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongianni F, Corda M, Fontana G, Pantaleo T. Influences of superior laryngeal afferent stimulation on expiratory activity in cats. J Appl Physiol. 1988;65:385–392. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.1.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongianni F, Mutolo D, Carfi M, Fontana GA, Pantaleo T. Respiratory neuronal activity during apnea and poststimulatory effects of laryngeal origin in the cat. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:917–925. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant TH, Yoshida S, de Castro D, Lipski J. Expiratory neurons of the Botzinger Complex in the rat: a morphological study following intracellular labeling with biocytin. J Comp Neurol. 1993;335:267–282. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran AK, Xia L, Leiter JC, Bartlett D., Jr Elevated body temperature enhances the laryngeal chemoreflex in decerebrate piglets. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:780–786. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00906.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Lawson EE. Synaptic events in ventral respiratory neurones during apnoea induced by laryngeal nerve stimulation in neonatal piglet. J Physiol. 1991;436:131–147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis PJ, Nail BS. On the location and size of laryngeal motoneurons in the cat and rabbit. J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:13–32. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RW, Richmond WH, Storey AT. Effect of medullary lesions on coordination of deglutition. Exp Neurol. 1967;17:91–106. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(67)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezure K. Synaptic connections between medullary respiratory neurons and considerations on the genesis of respiratory rhythm. Prog Neurobiol. 1990;35:429–450. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(90)90030-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezure K, Oku Y, Tanaka I. Location and axonal projection of one type of swallowing interneurons in cat medulla. Brain Res. 1993;632:216–224. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91156-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana GA, Lavorini F. Cough motor mechanisms. Resp Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;152:266–281. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa K, Yasuda K, Okuda D, Tanaka M, Yamaoka M. Central distribution and peripheral functional properties of afferent and efferent components of the superior laryngeal nerve: morphological and electrophysiological studies in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;375:147–156. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961104)375:1<147::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestreau C, Grelot L, Bianchi AL. Activity of respiratory laryngeal motoneurons during fictive coughing and swallowing. Exp Brain Res. 2000;130:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s002210050003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heman-Ackah YD, Pernell KJ, Goding GS. The laryngeal chemoreflex: An evaluation of the normoxic response. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:370–379. doi: 10.1002/lary.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikari T, Sasaki CT. Glottic closure reflex: control mechanisms. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980;89:220–224. doi: 10.1177/000348948008900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean A. Brain stem control of swallowing: neuronal network and cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:929–969. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Lipski J. Synaptic inputs to medullary respiratory neurons from superior laryngeal afferents in the cat. Brain Res. 1992;584:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90895-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler JP, Jean A. Inhibition of the swallowing reflex by local application of serotonergic agents into the nucleus of solitary tract. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;118:77–85. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90665-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler JP, Jean A. Effect of catecholamines on the swallowing reflex after pressure microinjection into the lateral solitary complex of the medulla oblongata. Brain Res. 1986;386:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobashi M, Xuan SY, Fujita M, Mitoh Y, Matsuo R. Central ghrelin inhibits reflex swallowing elicited by activation of the superior laryngeal nerve in the rat. Regul Peptides. 2010;160:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpas J, Jakus J. The expiration reflex from the vocal folds. Acta Physiol Hung. 2000;87:201–215. doi: 10.1556/APhysiol.87.2000.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucier GE, Daynes J, Sessle BJ. Laryngeal reflex regulation: peripheral and central neural analyses. Exp Neurol. 1978;62:200–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(78)90051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow CL. Central nervous system control of the laryngeal muscles in humans. Resp Phys Neurobiol. 2005;147:205–222. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oku Y, Tanaka I, Ezure K. Activity of bulbar respiratory neurons during fictive coughing and swallowing in the decerebrate cat. J Physiol. 1994;480:309–324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Shiba K, Nakazawa K, Shimoyama I. Synaptic origin of the respiratory-modulated activity of laryngeal motoneurons. Neuroscience. 2006;140:1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleo T, Corda M. Expiration-related neurons in the region of the retrofacial nucleus: vagal and laryngeal inhibitory influences. Brain Res. 1985;359:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91447-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens DL, Schefft G, Thach BT. Prolonged apnea associated with upper airway protective reflexes in apnea of prematurity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137:113–118. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky PM, Jiang C, Lipski J. An intracellular study of respiratory neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat and their relationship to catecholamine-containing neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1990;301:604–617. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers JE, Richter DW, Ballantyne D, Bainton CR, Klein JP. Reflex prolongation of stage I of expiration. Pflugers Arch. 1986;407:190–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00580675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Ezure K, Tanaka I. Swallowing-related activities of respiratory and non-respiratory neurons in the nucleus of solitary tract in the rat. J Physiol. 2002;540:1047–1060. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Ezure K, Tanaka I, Osawa M. Activity of neurons in ventrolateral respiratory groups during swallowing in decerebrate rats. Brain Dev. 2003;25:338–345. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba K, Nakazawa K, Ono K, Umezaki T. Multifunctional laryngeal premotor neurons: their activities during breathing, coughing, sneezing, and swallowing. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5156–5162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0001-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL. Pre-Botzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science. 1991;254:726–729. doi: 10.1126/science.1683005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q-J, Berkowitz RG, Pilowsky PM. GABAA mediated inhibition and post-inspiratory pattern of laryngeal constrictor motoneurons in rat. Resp Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;162:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q-J, Minson J, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Arnolda L, Chalmers J, Pilowsky P. Bötzinger neurons project towards bulbospinal neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:23–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971110)388:1<23::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun QJ, Berkowitz RG, Pilowsky PM. Response of laryngeal motoneurons to hyperventilation induced apnea in the rat. Resp Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;146:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Janczewski WA, Yang P, Shao XM, Callaway EM, Feldman JL. Silencing preBötzinger complex somatostatin-expressing neurons induces persistent apnea in awake rat. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:538–540. doi: 10.1038/nn.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach BT. Some aspects of clinical relevance in the maturation of respiratory control in infants. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1828–1834. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01288.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetmore RF. Effects of acid on the larynx of the maturing rabbit and their possible significance to the sudden infant death syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1242–1254. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia L, Damon T, Niblock MM, Bartlett D, Jr, Leiter JC. Unilateral microdialysis of gabazine in the dorsal medulla reverses thermal prolongation of the laryngeal chemoreflex in decerebrate piglets. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1864–1872. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00524.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Yatake K, Tanaka Y, Imamura R, Fukunaga H, Nakashima T, Hirano M. Morphological observation of laryngeal motoneurons by means of cholera toxin B subunit tracing technique. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1998;539:98–105. doi: 10.1080/00016489850182242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]