Abstract

Modification of proteins of the translational apparatus is common in many organisms. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we provide evidence for the methylation of Rpl1ab, a well conserved protein forming the ribosomal L1 protuberance of the large subunit that functions in the release of tRNA from the exit site. We show that the intact mass of Rpl1ab is 14 Da larger than its calculated mass with the previously described loss of the initiator methionine residue and N-terminal acetylation. We determined that the increase in mass of yeast Rpl1ab is consistent with the addition of a methyl group to lysine 46 using top-down mass spectrometry. Lysine modification was confirmed by detecting 3H-N-ϵ-monomethyllysine in hydrolysates of Rpl1ab purified from yeast cells radiolabeled in vivo with S-adenosyl-l-[methyl-3H]methionine. Mass spectrometric analysis of intact Rpl1ab purified from 37 deletion strains of known and putative yeast methyltransferases revealed that only the deletion of the YLR137W gene, encoding a seven-β-strand methyltransferase, results in the loss of the +14-Da modification. We expressed the YLR137W gene as a His-tagged protein in Escherichia coli and showed that it catalyzes N-ϵ-monomethyllysine formation within Rpl1ab on ribosomes from the ΔYLR137W mutant strain lacking the methyltransferase activity but not from wild-type ribosomes. We also showed that the His-tagged protein could catalyze monomethyllysine formation on a 16-residue peptide corresponding to residues 38–53 of Rpl1ab. We propose that the YLR137W gene be given the standard name RKM5 (ribosomal lysine (K) methyltransferase 5). Orthologs of RKM5 are found only in fungal species, suggesting a role unique to their survival.

Keywords: Covalent Regulation, Protein Methylation, Protein Synthesis, Ribosomes, S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM), Yeast, Methyltransferases

Introduction

Proteins of the eukaryotic translational apparatus are often targets for post-translational covalent modifications (1). One of the major types of these reactions is the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosylmethionine to a variety of residues including arginine (2–5), lysine (6–11), glutamine (12), histidine (13), and N-terminal (14, 15) residues. Ribosomal proteins (1–5, 7–11, 13, 14, 16), elongation factor 1A (1, 6, 17), and translational release factors (12) are common substrates of protein methyltransferases. These modifications are known to enhance resistance to ribosome-targeting antibiotics, facilitate ribosomal protein transport into and out of the nucleus, allow efficient ribosomal assembly, and increase translational accuracy (1, 5).

We have been interested in understanding the role of protein methylation in ribosomal function and assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a proteomics-guided approach. Previous efforts have identified modifications within proteins of the large ribosomal subunit. Interestingly, mass spectrometric analysis suggested that six proteins, Rpl1ab, Rpl3, Rpl12ab, Rpl23ab, Rpl42ab, and Rpl43ab,3 were subject to methylation (18). Further analysis has localized the methylation sites on four of these proteins. Rpl3 is modified to form a 3-methylhistidine residue at position 243 (13), whereas Rpl12ab is modified at three positions: a dimethylproline residue is present at the N terminus (14), an ϵ-trimethyllysine residue is found at position 3 (9, 19), and an unusual δ-monomethylarginine residue is found at position 66 (2). Rpl23ab is modified by ϵ-dimethyllysine formation at positions 105 and 109 (7), and Rpl42ab is modified by ϵ-monomethyllysine formation at positions 39 and 55 (9). The proposed methylation at Rpl43ab has not been observed to date in our studies. The only protein remaining to be analyzed is Rpl1ab.

In this work, we demonstrate that Rpl1ab from S. cerevisiae is modified at lysine 46 by the addition of a single methyl group. This protein is a member of the ribosomal L1 family that is conserved in most organisms and forms the “L1 protuberance” that is involved in tRNA exit from the E site of the large subunit (20–22). This protein binds not only the large subunit rRNA, but its own mRNA, the latter presumably in a regulatory role (21, 23). Interestingly, the protein structure appears to be flexible; no clear electron density is seen for L1 in the 2.4 Å map of the large subunit from the archaeon Haloarcula marismortui (24). We show here that methylation of the yeast L1 protein is absent in a deletion mutant of the putative seven-β-strand methyltransferase encoded by the YLR137W gene. We show that the expressed YLR137W protein can catalyze N-ϵ-monomethyllysine formation in yeast ribosomes containing unmethylated Rpl1ab and in a synthetic peptide corresponding to the methylated region on Rpl1ab. To date, most protein lysine methyltransferases have been identified as members of the SET domain methyltransferase family. However, the YLR137W gene product, now designated Rkm5, now joins four other protein lysine methyltransferases of the seven-β-strand superfamily: the Dot1 methyltransferase acting on histone H3 (25, 26), the CaM KMT acting on calmodulin (27), the See1 methyltransferase acting on elongation factor 1A (17), and the PrmA methyltransferase acting on prokaryotic ribosomal protein L11 (28).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Isolation of Ribosomal Proteins from S. cerevisiae Wild-type and Mutant Strains

The wild-type BY4742 and the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strain in the BY4742 background, as well as the deletion strains listed in supplemental Table S1, were obtained from the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project via Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). Intact 80 S ribosomes and large ribosomal subunits were isolated from the wild-type and ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strains as described previously (9). Proteins were extracted from the large ribosomal subunits with ethanol and acetic acid as described (29).

Liquid Chromatography with Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry of Intact Ribosomal Proteins

Ribosomal proteins extracted from the large subunit were fractionated using reverse phase liquid chromatography as described previously (9). The resulting effluent was directed into a QSTAR Elite (Applied Biosystems/MDX SCIEX) electrospray mass spectrometer running in MS-only mode. The instrument was calibrated using external peptide standards to yield a mass accuracy of 30 ppm or better.

Localization of Methylation Sites by Top-down Mass Spectrometry Using Collisionally Activated Dissociation and Electron Capture Dissociation

Proteins from the wild-type and ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strains were separated by HPLC as described above, and fractions containing Rpl1ab were directly infused on a hybrid linear ion trap Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (LTQ FT Ultra; Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) and fragmented using collisionally activated dissociation or electron capture dissociation as described previously (9). All of the MS/MS spectra were processed using ProSightPC software (Thermo Fisher) in single protein mode with a 15-ppm mass accuracy threshold. The root mean square deviations for assigned fragments were less than 5 ppm. The reference database for the ProSightPC software included the S. cerevisiae proteome from Swiss-Prot. Intact mass measurements were processed using the manual Xtract program, version 1.516 (Thermo Scientific).

Plasmid Construction and Expression of the Recombinant Yeast YLR137W/Rkm5 Fusion Protein

The BG1805 vector containing the yeast YLR137W/RKM5 gene was purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). The YLR137W/RKM5 open reading frame was cloned into the pET100/D-TOPO Escherichia coli expression vector as instructed (Invitrogen). Proper insertion into this vector was verified by full DNA sequencing (GENEWIZ, South Plainfield, NJ) using the standard T7 forward and T7 reverse primers. The vector pET100/D-TOPO encodes a His-tagged N-terminal linker sequence (MRGSHHHHHHGMASMTGGQQMGRDLYDDDDKDHPFT) that is followed by the complete amino acid sequence of the YLR137W/RKM5 open reading frame, including the initiator methionine residue. This plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Invitrogen). The recombinant protein was overexpressed by growing 2 liters of the transformed E. coli cells at 37 °C in LB medium with 100 μg/ml ampicillin to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.7 and then adding isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (Anatrace, Maumee, OH; catalog number I1003) to a final concentration of 0.4 mm. After 4 h, the cells were washed and resuspended in 20 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 4.3 mm Na2HPO4, 1.4 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and 100 μm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and were subsequently broken by ten 30-s sonicator pulses (50% duty; setting 4) on ice with a Sonifier cell disruptor W-350 (SmithKline Corp.). The lysate was centrifuged for 50 min at 13,000 × g at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was loaded onto a 5-ml HisTrap HP nickel affinity column (GE Healthcare part number 17-5248-1), and the fusion protein was purified using a gradient of 30–500 mm imidazole per the manufacturer's specifications.

RESULTS

The YLR137W Gene Is Required for the Modification of the Yeast Ribosomal Protein Rpl1ab

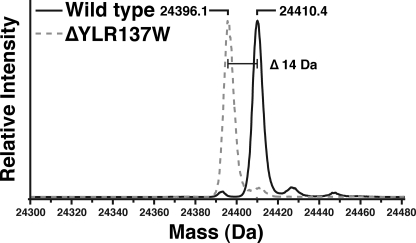

In an effort to identify new protein methyltransferases, yeast strains with deletions of known and putative methyltransferase genes were screened for loss of ribosomal protein methylation. Ribosomal proteins from large subunits of wild-type and 37 yeast deletion strains (supplemental Table S1) were isolated as previously described (19) and analyzed for their intact mass by mass spectrometry after HPLC separation (9). For the Rpl1ab protein, a mass of 24,410.4 Da was detected in the wild-type strain, corresponding to its predicted mass after the loss of the initiator methionine residue (30), N-terminal acetylation (30), and the addition of a methyl group (14 Da) (Fig. 1). This mass is consistent with previous observations (18). An identical mass at a similar HPLC retention time was observed in 36 of the 37 putative methyltransferase gene deletion strains. In the case of the YLR137W deletion strain, however, the 24,410-Da species was not observed, and a new species was detected at 24,396 Da, corresponding to the loss of the methyl group (Fig. 1). The YLR137W gene product was originally identified as a putative S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase by sequence analysis (31) and was recently classified as a member of the seven-β-strand methyltransferase superfamily (32). These results suggest that the YLR137W gene product is required for Rpl1ab methylation and that it may directly catalyze the transfer of the methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine to the ribosomal protein.

FIGURE 1.

Intact mass reconstruction of the large ribosomal protein Rpl1ab from wild-type (BY4742) and ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strains. Large ribosomal proteins were isolated from wild-type (BY4742) and the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strains using high salt sucrose gradients as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The proteins were separated from the rRNA and further fractionated using reverse phase HPLC. The resulting effluent was coupled to an electrospray mass spectrometer (QSTAR Elite), and the intact mass of each protein was measured. The resulting MS spectra of the Rpl1ab proteins were deconvoluted to yield the average mass of the protein. The loss of 14 Da, corresponding to the loss of a methylation event, is indicated.

The Large Ribosomal Protein Rpl1ab Is Modified in a Region Containing Lysine 46

To localize the site of the 14-Da modification within Rpl1ab, intact mass top-down mass spectrometry analysis was performed. Unbiased assignment of post-translational modifications across the entire polypeptide chain is possible using this approach, making it ideal for the assignment of post-translational modifications (33). Rpl1ab from yeast wild-type (BY4742) and the ΔYLR137W gene deletion strains was isolated as described above by reverse phase HPLC. Purified wild-type Rpl1ab was directly infused on a hybrid linear ion trap Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific LTQ FT Ultra) and fragmented using collisionally activated dissociation. This process localized the site of modification between lysine 46 and arginine 47 (Fig. 2). Similar analysis of Rpl1ab purified from the ΔYLR137W deletion strain demonstrated the absence of any 14-Da modification within the polypeptide chain (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Localization of the modification site on the Rpl1ab ribosomal protein by intact fragmentation. Rpl1ab was isolated from wild-type (BY4742) yeast strains as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Rpl1ab was subjected to top-down analysis where the intact protein was fragmented using collisionally activated dissociation producing “b” and “y” type cleavages (shown by upper and lower hash marks) or electron capture dissociation producing “c” and “z” type cleavages (shown by upper and lower horizontal lines). The site of the +14-Da modification is indicated by the gray box, localizing the site of methylation to lysine 46 or arginine 47. All y and z fragments terminating before arginine 47 were found to not contain an additional 14-Da mass; all of these fragments terminating before lysine 46 contained an additional mass of 14 Da. Similarly, all of the b and c fragments terminating before lysine 46 did not contain the additional mass of 14 Da; all of those terminating after arginine 47 did contain the 14 Da additional mass.

Rpl1ab Is Monomethylated at Lysine 46 by an S-Adenosylmethionine-dependent Methyltransferase

Wild-type (BY4742) yeast was in vivo labeled with [3H]AdoMet4 as described previously (29), and the large ribosomal proteins were isolated as described above. HPLC-purified Rpl1ab was acid hydrolyzed, and the products were separated using high resolution cation exchange chromatography (Fig. 3) and thin layer chromatography (Fig. 4). In Fig. 3, we show that the major 3H-methylated product elutes just slightly before a nonlabeled standard of ϵ-monomethyllysine. No radioactivity co-eluted with the ω-monomethylarginine or δ-monomethylarginine standards. It has been shown that tritium-labeled amino acids and similar compounds can be partially resolved from their unlabeled hydrogen forms with high resolution cation exchange chromatography (34–38), suggesting that the slight difference in retention times of the labeled amino acid and the unlabeled standard observed in Fig. 3 might be a result of an isotope effect. To confirm this, we also analyzed the labeled acid hydrolysates by thin layer chromatography (Fig. 4). Here, the radioactivity was found to migrate slightly slower than the ϵ-monomethyllysine standard. We considered the possibility that methylation might occur on the peptide bond nitrogen atom of the lysine residue rather than the side chain nitrogen. However, we found that a standard of N-α-methyllysine is clearly resolved from ϵ-monomethyllysine. These results provide strong evidence that that Rpl1ab is monomethylated at a lysine 46 by an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase and suggest an isotope effect for the migration of ϵ-monomethyllysine in thin layer chromatography and high resolution cation exchange chromatography.

FIGURE 3.

Rpl1ab contains a monomethyllysine residue. Wild-type (BY4742) cells were labeled in vivo with [3H]AdoMet as described previously (19), and large subunit ribosomal proteins were prepared by acetic acid and ethanol extraction as described (9). The Rpl1ab protein was purified using reverse phase HPLC (9), placed in a 6 × 50-mm glass vial, and dried down by vacuum centrifugation. Acid hydrolysis was then carried out by adding 50 μl of 6 n HCl to the vial and 200 μl of 6 n HCl to the reaction vial assembly (Eldex Laboratories, Napa, CA; catalog number 1163). The assembly was heated for 20 h in vacuo at 110 °C using a Waters Pico-Tag vapor phase apparatus. Residual HCl was removed by vacuum centrifugation, and the free amino acids were resuspended in 50 μl of water and 500 μl of pH 2.2 sodium citrate buffer (0.2 m Na+). Standards of methylated amino acids purchased from Sigma included ϵ-N-monomethyllysine hydrochloride (M6004), asymmetric NG,NG-dimethylarginine dihydrochloride (D4268), symmetric NG,NG′-dimethyl-l-arginine di(p-hydroxyazobenzene-p′-sulfonate (D0390), and ω-NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate (M7033). 3-Methyl-l-histidine (or τ-methyl-l-histidine) was purchased from Aldrich (67520). After the addition of 1.0 μmol of each standard, fractionation was performed on a column of PA-35 sulfonated polystyrene beads (0.9-cm inner diameter × 10-cm column height; 6–12-μm bead diameter; Benson Polymeric Inc., Reno, NV). The column was equilibrated and eluted at 55 °C with pH 5.27 sodium citrate buffer (0.35 m Na+) at 1 ml/min; regeneration was performed by elution with 0.2 n NaOH for 25 min. One-minute fractions were collected. The elution positions of the standards were identified by a ninhydrin assay (dashed line). Briefly, 100 μl of each column fraction was mixed with 600 μl of water and 300 μl of a solution of 20 mg/ml ninhydrin and 3 mg/ml hydrindantin in a solvent of 75% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide and 25% (v/v) 4 m pH 4.2 lithium acetate buffer. The mixture was then heated at 100 °C for 15 min, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Radioactivity (solid line) was determined by mixing 900 μl of the fraction with 400 μl of water and 10 ml of fluor (Safety Solve, Research Products International) followed by counting for three 5-min periods on a Beckman LS6500 instrument with a measured tritium efficiency of 55%. In this chromatography system, δ-monomethylarginine elutes near the position of symmetric dimethylarginine (31). The slightly earlier elution of the radioactivity compared with the monomethyllysine standard is consistent with the isotopic separation of the 3H-methylated versus the 1H-methylated species (34–38).

FIGURE 4.

Thin layer chromatography confirms the presence of ϵ-monomethyllysine in Rpl1ab. In vivo [3H]methylated Rpl1ab was prepared from wild-type (BY4742) cells as described in the Fig. 3 legend. The sample was acid hydrolyzed, dried, and resuspended in water and 5 nmol of each of the following standards: l-lysine, ϵ-monomethyllysine, ϵ-dimethyllysine, and ϵ-trimethyllysine (see Fig. 3 legend). Ascending separation was performed using a 20 × 20-cm silica-coated plate (Whatman, PE SIL G/UV) after preincubating the chamber with the mobile phase methanol: ammonium hydroxide (4:1). The origin is indicated with an arrow by fraction 1; the solvent front was run near the end of the plate to fraction 67. Ninhydrin reagent was used to detect the migration of the internal standards (indicated by ovals), along with individual standards run in adjacent lanes to determine the migration distance for each lysine derivative. After drying, the plate was sprayed with a ninhydrin solution consisting of 1 g of ninhydrin, 2.5 g of cadmium acetate, 10 ml of acetic acid, and 500 ml of ethanol and then heated at 100 °C for 20 min. To detect radioactivity, the lane was cut into ∼3-mm slices as indicated by the vertical lines, and each slice was placed into a microcentrifuge tube with 300 μl of water and incubated overnight shaking at room temperature. The silica gel was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was counted for radioactivity with 5 ml of fluor (Safety Solve; Research Products International) using a Beckman LS6500 instrument for three 5-min counting cycles.

Modification of an ∼24-kDa Large Ribosomal Protein by Purified YLR137W/Rkm5

To determine whether the YLR137W gene product might directly methylate the Rpl1ab protein, a recombinant His-tagged form of YLR137W was expressed in E. coli and purified for in vitro methylation assays. When intact 80 S ribosomal subunits isolated from the ΔYLR137W deletion strain were incubated with the His-tagged YLR137W protein and [3H]AdoMet and size-fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, we were able to detect methylation of a 24-kDa polypeptide species, which corresponds to the size of Rpl1ab (Fig. 5). This methylation activity was only observed with intact 80 S ribosomes isolated from the ΔYLR137W deletion strain; this methylation was not observed in wild-type 80 S ribosomes (Fig. 5). These results suggest that YLR137W is a methyltransferase capable of recognizing and methylating Rpl1ab on the ribosome. The lack of in vitro methylation of Rpl1ab in ribosomes prepared from wild-type cells (Fig. 5) reflects the stoichiometric methylation of Rpl1ab (Fig. 1); there is no unmethylated polypeptide available as a substrate in these cells.

FIGURE 5.

Recombinant YLR137W/Rkm5 methylates a ∼24-kDa polypeptide from intact ribosomes isolated from the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 yeast deletion strain. Intact ribosomes were isolated from wild-type (BY4742) and the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 yeast deletion strain and were methylated in vitro with recombinant His-tagged YLR137W/Rkm5. 80 S ribosomes (45 μg of protein) from the wild type (lanes 1 and 2) or from the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 (lanes 3 and 4) yeast deletion strain were incubated with (lanes 2 and 4) or without (lanes 1 and 3) 5 μg of His-YLR137W/Rkm5 in 1 μm [3H]AdoMet, 100 mm NaCl, 100 mm Na2HPO4 at pH 7.0 for 60 min at 30 °C in a final volume of 100 μl. The polypeptides in the incubation mixtures were separated on a SDS-PAGE gel (NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Invitrogen) and Coomassie-stained and destained (upper panel). The gel was then treated with EN3HANCE (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) for 1 h, followed by a 20-min wash in water. The gel was dried under vacuum for 2 h at 80 °C followed by 1 h without heat and placed on Kodak BIOMAX XAR film for 2 weeks. A fluorograph is shown (lower panel). Methylation of a ∼24-kDa polypeptide (corresponding to the molecular weight of the Rpl1ab) is seen in the reactions containing 80 S ribosomes from the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strain and His-YLR137W/Rkm5. The arrowhead marks the position of methylated Rpl1ab; the molecular mass markers (Bio-Rad; low molecular weight) are shown in kDa.

Recombinantly Expressed YLR137W/Rkm5 Produces Monomethyllysine

We next examined the specific amino acid residue methylated by His-tagged YLR137W/Rkm5. His-YLR137W/Rkm5 was incubated with intact 80 S ribosomes derived from the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strain in the presence of radiolabeled [3H]AdoMet or [14C]AdoMet. Methylated proteins were acid hydrolyzed and analyzed by thin layer chromatography (Fig. 6). The reaction with [3H]AdoMet produced a product that migrated less rapidly than the ϵ-monomethyllysine standard (Fig. 6, upper panel), similar to the migration pattern observed in the in vivo methylation experiment in Fig. 4. When a [14C]AdoMet substrate was used in the in vitro reaction with His-tagged YLR137W/Rkm5; however, the 14C-product co-migrated with the unlabeled ϵ-monomethyllysine standard (Fig. 6, lower panel), showing that Rpl1ab contains a ϵ-monomethyllysine residue. These results demonstrate that 3H-isotope effects can occur in thin layer chromatography as well as in high resolution cation exchange chromatography (34–38).

FIGURE 6.

Recombinant His-YLR137W/Rkm5 produces monomethyllysine. Intact ribosomes isolated from the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 deletion strain were methylated in vitro with His-YLR137W/Rkm5 as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Intact ribosomes (45 μg of protein) isolated from the ΔYLR137W/rkm5 yeast deletion strain were incubated with 1 μm [3H]AdoMet (PerkinElmer; 75–85 Ci/mmol, from a 7 μm stock solution in 10 mm H2SO4/ethanol (9:1, v/v) (upper panel) or 20 μm [14C]AdoMet (Amersham Biosciences; 55.8 mCi/mmol, from a 448 μm stock solution in dilute sulfuric acid, pH 2.5–3.5) (lower panel) with 58 μg of the recombinant His-YLR137W/Rkm5 protein (prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures,” in 100 mm NaCl, 100 mm sodium phosphate at pH 7.0) at 30 °C for 16 h in a final volume of 100 μl. Methylated proteins were precipitated by the addition of an equal volume of 25% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid, incubation for 30 min at room temperature, and centrifugation at 2,700 × g for 30 min. The precipitated protein pellet was washed with 100 μl of cold acetone, acid hydrolyzed, and dried as described above. After mixing the pellet with 5 μl of water and 10 nmol of each of the amino acid standards, ascending thin layer chromatographic separation was performed using a silica-coated plate as described in the Fig. 4 legend. The standards were visualized using ninhydrin, and radioactivity was detected for each 5-mm section (indicated by vertical lines) as described in the Fig. 4 legend. The arrow marks the origin by fraction 1; the solvent front was run near the end of the plate to fraction 38. The slightly slower migration of the 3H-methyl-labeled monomethyllysine derivative (upper panel) as compared with the 14C methyl-labeled derivative (lower panel) appears to be due to a tritium isotope effect (see text).

Purified YLR137W/Rkm5 Catalyzes the Methylation of a Synthetic Peptide with the Rpl1ab Sequence from Residues 38 to 53

To ask whether the purified YLR137W gene product was sufficient to catalyze the methylation reaction or whether it required other factors present on the ribosome, as well as to determine whether tertiary structure is needed for the methylation reaction, we incubated the recombinant protein with a short synthetic peptide including the unmodified target lysine residue. When incubated with [3H]AdoMet and enzyme, radioactivity was found to elute with the peptide when the reaction products were separated by HPLC (Fig. 7A). In a control reaction without peptide, no radioactivity was seen. However, in a control reaction without enzyme (peptide only), some radioactivity was also detected at the elution position of the peptide. Nevertheless, when peptide-containing HPLC fractions were acid hydrolyzed and analyzed by high resolution cation exchange chromatography, radioactivity eluting with a monomethyllysine standard was only found in the samples incubated with both peptide and enzyme (Fig. 7B). Importantly, these results provide direct evidence that the YLR137W gene product has by itself methyltransferase activity and is capable of recognizing a short sequence derived from Rpl1ab. We now propose that the YLR137W gene be given the standard name RKM5 for ribosomal lysine (K) ethyltransferase 5.

FIGURE 7.

Monomethylation of a lysine residue in a synthetic peptide derived from Rpl1ab by recombinant His-YLR137W/Rkm5. A, a 16-amino acid synthetic peptide (KNYDPQRDKRFSGSLK) was prepared by Biosynthesis, Inc. (Lewisville, TX) corresponding to residues 38–53 of Rpl1ab. Peptide (60 μg) was incubated with (squares) or without (triangles) recombinant His-YLR137W/Rkm5 (60 μg), 1 μm [3H]AdoMet, 100 mm NaCl, 100 mm Na2HPO4 at pH 7 as described in Fig. 6 for 16 h at 30 °C in a final volume of 200 μl. An additional incubation with enzyme but without peptide was also prepared (circles, solid line). The reactions were terminated by adding 20 μl of 10% trifluoroacetic acid. After centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, the supernatant was fractionated by HPLC using a 150 × 2-mm PLRP-S polymeric column with a pore size of 300 Å and a bead size of 5 μm (Polymer Laboratories, Amherst, MA). The column was maintained at 50 °C and initially equilibrated in 95% solvent A (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water) and 5% solvent B (0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile). The peptides were eluted at a flow rate of 500 μl/min using a program of 20 min at 5% B, followed by a 25-min gradient to 60% B; half-minute fractions were collected. The elution position of the peptide was determined from the absorbance at 280 nm (dashed line). 50-μl aliquots from fractions eluting at 25–35 min were counted for radioactivity as described in Fig. 3 but with 5 ml of fluor for three 3-min counting cycles. The values shown were normalized to the total volume of each fraction. B, HPLC fractions from 25–35 min in A above were combined for the peptide-only reaction (triangles) and for the peptide and enzyme reaction (squares) and dried by vacuum centrifugation. The resulting peptides were then acid hydrolyzed, dried as in Fig. 3, and then mixed with 50 μl of water, 150 μl of pH 2.2 citrate buffer, and a standard of 10 μl of 0.2 m ϵ-monomethyllysine. Amino acid fractionation was performed as described in Fig. 3 except with a buffer of pH 5.84 sodium citrate (0.2 m Na+). The elution position of the monomethyllysine standard was identified by a ninhydrin assay (dashed line). Briefly, 30 μl of each column fraction was mixed with 200 μl of water and 100 μl of a solution of 20 mg/ml ninhydrin and 3 mg/ml hydrindantin in a solvent of 75% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide and 25% (v/v) 4 m pH 4.2 lithium acetate buffer. The mixture was then heated at 100 °C for 15 min, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader. Radioactivity (solid lines) was determined by mixing 400 μl of sample with 10 ml of fluor and counting as described for A. The values are shown normalized to the total volume for each fraction and for the portion of the HPLC fractions hydrolyzed. The slightly earlier elution of the radioactivity compared with the standard is consistent with the isotopic separation of the 3H-methylated versus the 1H-methylated species (34–38).

Rkm5 Orthologs Are Limited to Fungal Species

A BLAST search revealed proteins with sequence similarity to YLR137W/Rkm5 in a number of fungal species, but not in proteins from other organisms (Fig. 8). The closest nonfungal species identified in a BLAST search is the Arabidopsis thaliana protein NP_973791.1 (57 of 282 identities, expect value = 0.003). This Arabidopsis protein matches more closely to the yeast YNL024C putative methyltransferase and to the yeast N-terminal Xaa-Pro-Lys methyltransferase, indicating that the Rpl1ab modification may be unique to fungi. We note, however, that the amino acid sequence adjacent to the methylated lysine 46 residue (DKRF) in S. cerevisiae Rpl1ab is highly conserved in the L1 ribosomal protein family in eukaryotic cells, including protozoans, fungi, plants, invertebrates, and vertebrates. This suggests that this region of Rpl1ab might have a critical role in ribosomal function. Although this specific short sequence is not conserved in prokaryotic L1 ribosomal proteins, the arginine residue adjacent to lysine 46 is conserved in a larger sequence context in a number of archaea. We suspect that the Rkm5 enzyme may have evolved to fulfill a specific need of fungal species, perhaps allowing them to thrive in unique environmental conditions.

FIGURE 8.

S. cerevisiae YLR137W/RKM5 homologs are present in fungi. BLAST searches were performed against the yeast YLR137W/RKM5 sequence to identify homologs in other organisms and ClustalW was used to align sequences. Signature methyltransferase motifs common to all class I protein methyltransferases are boxed. The UniProt identification designation, corresponding protein name if given, and BLAST expect value for each sequence identified are as follows: Aspergillus fumigatus (Q4X1H7; expect value, 10−8), Neurospora crassa (Q7RZ91; expect value, 7 × 10−5), Candida albicans (C4YJI9; expect value, 2 × 10−18), S. cerevisiae (YLR137W/RKM5, Q12367), and S. pombe (diaminohydroxyphosphoribosylamino-pyrimidine deaminase, P87241; expect value, 4 × 10−5). The closest human homolog is the FAM86B2 protein (UniProt P0C5J1) with an expect value of 0.78. The S. pombe sequence contains a hypothetical pyrimidine deaminase domain in the C-terminal region adjacent to the aligned sequence. Light gray shading indicates sites where three residues are identical, medium gray shading indicates sites where four residues are identical, and dark gray shading indicates sites where all of the residues are identical.

To directly test the biological role of Rpl1ab methylation, we tested the sensitivity of rkm5 mutant cells to translational inhibitors that bind near the aminoacyl- and peptidyl-tRNA sites, including cycloheximide, hygromycin B, and verrucarin A. Using disk diffusion assays with different amounts of antibiotics, we found no difference in the zones of antibiotic inhibition between the parent and Δrkm5 strains. Furthermore, growth assays were done in the presence of antibiotics, and similarly, there was no significant difference in growth rate between parent and the Δrkm5 mutant. These results indicate that further experiments will be needed to determine how the Rpl1ab modification may fine-tune ribosomal function.

DISCUSSION

The Rpl1ab protein in yeast is a member of the highly conserved L1 ribosomal protein family. These proteins form the L1 protuberance, an extension from the large ribosomal subunit that is suggested to facilitate the exit of the tRNA from the E site (22). Although there is no high resolution structure of the yeast ribosome, it is possible to estimate the three-dimensional site of the lysine 46 modification by studying the known structures of bacterial (23) and archaeal (21) L1 proteins in complex with rRNA. Although the lysine 46 residue of yeast Rpl1ab is not generally conserved in prokaryotes, its position has been established between the first and second β-strands, away from the RNA binding interfaces (21, 23). This suggests that the side chain of lysine 46 of Rpl1ab may be accessible on the surface of the ribosome, in contrast to the methylated lysine residues of yeast Rpl23ab (19) and Rpl42ab (9), as well as the methylated histidine residue of Rpl3 (13) that appear to interact directly with rRNA. Interestingly, the lysine 46 residue and its surrounding sequence is well conserved in the mammalian L1 ortholog, Rpl10A. It is not clear whether the mammalian protein might also be subject to methylation.

The Rkm5 methyltransferase joins a growing family of enzymes of the seven-β-strand class (32, 39) that catalyze protein lysine methylation. Until recently, nearly all of the protein lysine methyltransferases were of the SET domain class, with the key exception being the Dot1 enzyme that was responsible for the trimethylation of Lys-79 in histone H3 (25, 26). Others have now identified seven-β-strand enzymes that catalyze the trimethylation and dimethylation of lysine residues in calmodulin (27) and elongation factor 1A (17), respectively. Additionally, evidence has been presented that PrmA, the seven-β-strand methyltransferase responsible for the N-terminal methylation of prokaryotic ribosomal protein L11, also catalyzes trimethylation of lysine residues at two sites within the polypeptide (28). We analyzed the amino acid sequences surrounding the methylated lysine residue in each of these proteins and did not identify any common sequence motifs that might serve as recognition sequences for seven β-strand protein lysine methyltransferases (data not shown). It is clear, however, that protein lysine methylation is catalyzed by members of both the SET domain and seven-β-strand methyltransferase superfamilies.

Interestingly, protein lysine methylation appears to be more common in fungal species than in mammalian species, at least for ribosomal proteins of the large subunit (Table 1). Notably, there are no mammalian orthologs of any of the five yeast ribosomal large subunit protein lysine methyltransferases described to date (Table 1). Moreover, none of the human orthologs of the methylated yeast Rpl1ab, Rpl12ab, Rpl23ab, and Rpl42ab proteins appear to be modified (41). The only human large subunit ribosomal protein known to be modified by lysine methylation is L29 (41); the yeast Rpl29 ortholog is unmodified (18). In rat ribosomes, protein lysine methylation has been detected in both L29 and L40 (42); neither yeast ortholog is modified (18).

TABLE 1.

Protein lysine methyltransferases in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have few mammalian orthologs

| Methyltransferase gene product | Methyltransferase superfamily | Substrate and methylated productsa | Methyltransferase ortholog in mammals? | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rkm1 (YPL208W) | SET domain | Rpl23ab | No | 7 |

| Dimethyllysine 105 | ||||

| Dimethyllysine 109 | ||||

| Rkm2 (YDR198C) | SET domain | Rpl12ab | No | 19 |

| Trimethyllysine 3 | ||||

| Rkm3 (YBR030W) | SET domain | Rpl42ab | No | 9 |

| Monomethyllysine 40 | ||||

| Rkm4 (YDR257C) | SET domain | Rpl42ab | No | 9 |

| Monomethyllysine 55 | ||||

| Rkm5 (YLR137W) | Seven-β-strand | Rpl1ab | No | This study |

| Monomethyllysine 46 | ||||

| Efm1 (YHL039W) | SET domain | eEF1A | No | 17 |

| Monomethyllysine 30 or 390?b | ||||

| See1 | Seven-β-strand | eEF1A | Yes | 17 |

| (YIL064W) | Dimethyllysine 316?c | (human METTL10)e | ||

| Ctm1 (YHR109W) | SET domain | Cytochrome c Trimethyllysine 77d | No | 40 |

| Dot1 (YDR440W) | Seven-β-strand | Histone H3 | Yes | 25, 26 |

| Trimethyllysine 79 | (human DOT1L)f |

a Residue numbering based on mature protein (loss of initiator methionine) except for Rpl42ab and eEF1A.

b Sites of methylation suggested based on location of known monomethylated sites in yeast eEF1A (6, 17).

c Site of methylation suggested based on location of known dimethylated site in yeast eEF1A (6, 17).

d Methylation site in isoform 1; site at lysine 81 in isoform 2.

e 38% amino acid sequence identity over 182 residues.

f 28% amino acid sequence identity over 297 residues.

Variation of ribosomal protein lysine methylation patterns is also seen in other organisms. In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, enzyme orthologs of S. cerevisiae Rkm2 (10) and Rkm4 (11) catalyze the methylation of lysine 3 of Rpl12 and lysine 55 of Rpl42, respectively. In the higher plant A. thaliana, lysine 3 of L12 is trimethylated, and lysine 55 of L36a (the Rpl42 ortholog) is monomethylated (8) as seen in S. cerevisiae (9) and S. pombe (10). Although L10a, the Arabidopsis ortholog of S. cerevisiae Rpl1ab, is methylated, the site and degree of methylation is different (trimethylation at lysine 90 rather than monomethylation at lysine 46) (8). In other organisms, more extensive differences occur. In the ciliate protozoan Tetrahymena thermophila, lysine methylation has only been detected in one large subunit ribosomal protein (43). In the bacterium E. coli, the L11 protein (the ortholog of yeast Rpl12ab) is methylated at lysine 3 (the equivalent position methylated in plants and yeast) and at one additional nonconserved site (lysine 39) by the PrmA methyltransferase (44). This enzyme, however, shows little or no similarity to the yeast ribosomal lysine methyltransferase Rkm5 except within the general motifs I, post-I, II, and III, common to all seven β-strand methyltransferases. In fact, the closest match of E. coli PrmA in S. cerevisiae is Rmt1 protein arginine methyltransferase. Ribosomal protein L12 in E. coli is also methylated at a lysine residue (45); there is no yeast cytoplasmic ortholog of this protein. These results demonstrate that protein lysine methylation on the large ribosomal subunit is largely idiosyncratic in nature with little in common between more distinct groups of organisms despite the similarity in the protein sequences themselves.

The role of protein lysine methylation of ribosomal proteins is unclear. Some information is available from the phenotype of yeast cells lacking specific protein lysine methyltransferases. Yeast cells lacking the YLR137W/Rkm5 methyltransferase are viable and do not yet have a clear phenotype. When grown in a competition with a parent strain in minimal medium, the YLR137W knock-out shows a slight growth advantage (relative fitness score is 1.003) (46). In both S. cerevisiae and S. pombe, cells lacking methylation at lysine 55 of Rpl42 are more sensitive to cycloheximide (9, 11), and S. pombe mutants have survival defects in stationary phase (11). The growth defect in S. pombe resulting from the overexpression of the enzyme responsible for lysine 3 methylation of Rpl12, as well as the nucleolar localization of the enzyme, suggests a role for methylation in ribosomal assembly. More generally, protein lysine methylation has been associated with increases in protein stability. The chemical introduction of ϵ-dimethyllysine residues in bovine trypsin results in decreased autolysis (47) and in enhanced surface contacts in crystal structures (48). The thermal stability of β-glycosidase from the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus is dependent upon the methylation of five of the 23 lysine residues (49). It has also been suggested that lysine side chain methylation generally increases the stability of proteins, exemplified by the extensive modification of several proteins in the thermophilic archaeon Thermoproteus tenax, where 52 methylated lysine residues were detected in 30 different proteins (50). Taken together, these results suggest that ribosomal protein lysine methylation may play multiple roles and may act to allow optimization of ribosomal function to allow organisms to thrive in a wide range of growth environments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Mass spectrometry was performed in the UCLA Molecular Instrumentation Center. We thank Joseph Loo, Puneet Souda, Kym F. Faull, and Julian P. Whitelegge for continuing help.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM026020.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1.

Yeast ribosomal proteins are identified based on the gene designation. In cases where two genes encode identical protein products, the protein is designated “ab.” For example, the Rpl1ab protein is the identical translation product of the RPL1A and RPL1B genes.

- [3H]AdoMet

- S-adenosyl-l-[methyl-3H]methionine

- [14C]AdoMet

- S-adenosyl-l-[methyl-14C]methionine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Polevoda B., Sherman F. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 65, 590–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chern M. K., Chang K. N., Liu L. F., Tam T. C., Liu Y. C., Liang Y. L., Tam M. F. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15345–15353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olsson I., Berrez J. M., Leipus A., Ostlund C., Mutvei A. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313, 1778–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Swiercz R., Cheng D., Kim D., Bedford M. T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16917–16923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ren J., Wang Y., Liang Y., Zhang Y., Bao S., Xu Z. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12695–12705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cavallius J., Zoll W., Chakraburtty K., Merrick W. C. (1993) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1163, 75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Porras-Yakushi T. R., Whitelegge J. P., Clarke S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12368–12376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carroll A. J., Heazlewood J. L., Ito J., Millar A. H. (2008) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 347–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Webb K. J., Laganowsky A., Whitelegge J. P., Clarke S. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35561–35568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sadaie M., Shinmyozu K., Nakayama J. I. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7185–7195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shirai A., Sadaie M., Shinmyozu K., Nakayama J. I. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22448–22460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schubert H. L., Phillips J. D., Hill C. P. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 5592–5599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Webb K. J., Zurita-Lopez C. I., Al-Hadid Q., Laganowsky A., Young B. D., Lipson R. S., Souda P., Faull K. F., Whitelegge J. P., Clarke S. G. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37598–37606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Webb K. J., Lipson R. S., Al-Hadid Q., Whitelegge J. P., Clarke S. G. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 5225–5235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tooley C. E., Petkowski J. J., Muratore-Schroeder T. L., Balsbaugh J. L., Shabanowitz J., Sabat M., Minor W., Hunt D. F., Macara I. G. (2010) Nature 466, 1125–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lhoest J., Colson C. (1990) in Protein Methylation (Paik W. K., Kim S. eds) pp. 155–178, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lipson R. S., Webb K. J., Clarke S. G. (2010) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 500, 137–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee S. W., Berger S. J., Martinović S., Pasa-Tolić L., Anderson G. A., Shen Y., Zhao R., Smith R. D. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5942–5947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Porras-Yakushi T. R., Whitelegge J. P., Clarke S. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35835–35845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Petitjean A., Bonneaud N., Lacroute F. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 5071–5081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nikulin A., Eliseikina I., Tishchenko S., Nevskaya N., Davydova N., Platonova O., Piendl W., Selmer M., Liljas A., Drygin D., Zimmermann R., Garber M., Nikonov S. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cornish P. V., Ermolenko D. N., Staple D. W., Hoang L., Hickerson R. P., Noller H. F., Ha T. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2571–2576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nevskaya N., Tishchenko S., Volchkov S., Kljashtorny V., Nikonova E., Nikonov O., Nikulin A., Köhrer C., Piendl W., Zimmermann R., Stockley P., Garber M., Nikonov S. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 355, 747–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ban N., Nissen P., Hansen J., Moore P. B., Steitz T. A. (2000) Science 289, 905–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feng Q., Wang H., Ng H. H., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Struhl K., Zhang Y. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, 1052–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Leeuwen F., Gafken P. R., Gottschling D. E. (2002) Cell 109, 745–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Magnani R., Dirk L. M., Trievel R. C., Houtz R. L. (2010) Nat. Commun. 1, 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Demirci H., Gregory S. T., Dahlberg A. E., Jogl G. (2008) Structure 16, 1059–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Porras-Yakushi T. R., Whitelegge J. P., Miranda T. B., Clarke S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 34590–34598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Polevoda B., Sherman F. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 325, 595–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Niewmierzycka A., Clarke S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 814–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petrossian T., Clarke S. (2009) Epigenomics 1, 163–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pesavento J. J., Bullock C. R., LeDuc R. D., Mizzen C. A., Kelleher N. L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14927–14937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kleene S. J., Toews M. L., Adler J. (1977) J. Biol. Chem. 252, 3214–3218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clarke S., McFadden P. N., O'Connor C. M., Lou L. L. (1984) Methods Enzymol. 106, 330–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gary J. D., Lin W. J., Yang M. C., Herschman H. R., Clarke S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 12585–12594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Klein P. D., Szczepanik P. A. (1967) Anal. Chem. 39, 1276–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gottschling H., Freese E. (1962) Nature 196, 829–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Petrossian T. C., Clarke S. G. (2009) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 1516–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Polevoda B., Martzen M. R., Das B., Phizicky E. M., Sherman F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20508–20513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Odintsova T. I., Müller E. C., Ivanov A. V., Egorov T. A., Bienert R., Valdimirov S. N., Kostka S., Otto A., Wittmann-Liebold B., Karpova G. G. (2003) J. Protein Chem. 22, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Williamson N. A., Raliegh J., Morrice N. A., Wettenhall R. E. (1997) Eur. J. Biochem. 246, 786–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guérin M. F., Hayes D. H., Rodrigues-Pousada C. (1989) Biochemie 71, 805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vanet A., Plumbridge J. A., Guérin M. F., Alix J. H. (1994) Mol. Microbiol. 14, 947–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Arnold R. J., Reilly J. P. (1999) Anal. Biochem. 269, 105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Breslow D. K., Cameron D. M., Collins S. R., Schuldiner M., Stewart-Ornstein J., Newman H. W., Braun S., Madhani H. D., Krogan N. J., Weissman J. S. (2008) Nat. Methods. 5, 711–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rice R. H., Means G. E., Brown W. D. (1977) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 492, 316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sledz P., Zheng H., Murzyn K., Chruszcz M., Zimmerman M. D., Chordia M. D., Joachimiak A., Minor W. (2010) Protein Sci. 19, 1395–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Febbraio F., Andolfo A., Tanfani F., Briante R., Gentile F., Formisano S., Vaccaro C., Scirè A., Bertoli E., Pucci P., Nucci R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10185–10194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Botting C. H., Talbot P., Paytubi S., White M. F. (2010) Archaea 2010, 106341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.