Abstract

Carval syndrome is a severe heartworm infection where the worms have migrated to the right atrium and vena cava; this condition is associated with a myriad of clinical signs. Several non-surgical and interventional methods are currently used for mechanical worm removal. However, the success rate and complications related to these methods are heavily dependent on methodology and retrieval devices used. In this study, we developed a catheter-guided heartworm removal method using a retrieval basket that can easily access pulmonary arteries and increase the number of worms removed per procedure. With this technique, we successfully treated four dogs with caval syndrome.

Keywords: basket, caval syndrome, dog, heartworm, mechanical heartworm removal

Caval syndrome in dogs is a severe variant or complication of heartworm disease (HWD) due to a heavy worm burden with the majority of worms residing in the right atrium and vena cava [2,3]. Severe complications associated with immiticide therapy, such as a marked host immune response against dead worms, caused surgical or mechanical heartworm removal (worm embolectomy) to be generally preferred for treating dogs with caval syndrome [1,2]. A recent study found that a catheter-guided technique for worm removal using alligator and tripod forceps improves access to the pulmonary arteries, and minimizes vascular and intra-cardiac damage often associated with blind grasping of the retrieval forceps [1]. However, the retrieval rate per extraction was 1~3 worms when this retrieval device was used. Thus, a substantial number of extraction trials would be necessary to remove all the heartworms residing in the right atrium and pulmonary arteries. Furthermore, this method is associated with the risk of accidental intra-cardiac damage by forceps although this is considerably lower than that associated with conventional retrieval methods. To improve the efficiency and safety of mechanical heartworm removal, we developed a new catheter-guided heartworm removal method using a retrieval basket.

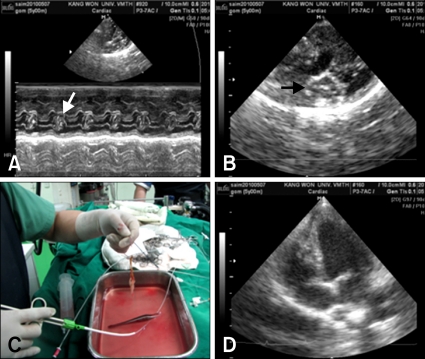

The first case in our study was a 7-year-old intact mixed male dog (body weight 4.5 kg). The dog presented with hemoglobinuria, severe cough, and exercise intolerance. Heart auscultation revealed a grade V/VI systolic regurgitant murmur in the right and left apex. The main laboratory findings were hypochromic anemia (packed cell volume 28.3%, reference range 37~55%; hemoglobin 9.7 g/dL, reference range 12~18 g/dL), leukocytosis (total number of white blood cells, 21.8 K/uL, reference range 6~17 K/uL) with eosinophilia, hypoproteinemia (total protein, 5.0 g/dL, reference range 5.4~8.2 g/dL), and prerenal azotemia (blood urea nitrogen, 40 mg/dL, reference range 7~25 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.0 mg/dL, reference range 0.3~1.4 mg/dL). Both the immunological test (SNAP 4Dx; Idexx, USA) for adult worms and the microscopic examination for microfilaria were positive. Thoracic radiography revealed a right-sided cardiomegaly (reverse 'D' shape) with marked dilation of the main pulmonary artery and caudal vena cava. Echocardiographic examination revealed a septal flattening of the right ventricle (due to a marked elevation of right ventricular pressure), severe pulmonary (pulmonic regurgitant velocity, 4.32 m/sec) and tricuspid regurgitation (tricuspid regurgitant velocity, 4.2 m/sec), and marked right atrial enlargement. Hyperechogenic clumps (consistent with a heavy worm burden) moving from the right ventricle to right atrium was clearly visualized by echocardiography (Figs. 2A and B). Further echocardiographic examination also revealed a moderate mitral regurgitation (mitral regurgitant velocity, 5.1 m/sec) due to degenerative changes in the mitral valves.

Fig. 2.

Echocardiography and clinical outcomes. (A) M-mode echocardiography revealed clumps (arrow) of heartworms in the right ventricle due to heavy worm burden. (B) B-mode echocardiography showed heartworms migrating from the right ventricle to the right atrium (arrow). (C) Multiple worm removal per trial in a dog (Case 2). (D) Disappearance of heartworms from the right atrium and ventricle after the removal procedure on B-mode echocardiography in a dog (Case 1).

Percutaneous heartworm removal was performed. In order to minimize the side effect of the procedure, the dog was given prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg, BID, PO; Daewoo, Korea), doxycycline (5 mg/kg, BID, PO; Pfizer, USA) and clopidogrel (2~4 mg/kg, SID, PO; Sanofi-Aventis, France) 1 week prior to the procedure. Enoxaparin (100 U/kg; Sanofi-Aventis, France) was also administered subcutaneously 1 day prior to the procedure and tramadol (2 mg/kg, subcutaneous administration, Daewoong, Korea) was given just before the operation for pain control.

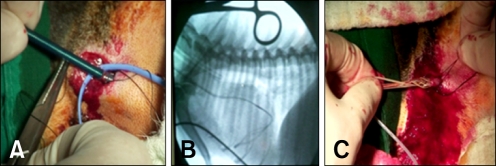

The dogs were premedicated with or without atropine (0.05 mg/kg, subcutaneous administration; Daewoo, Korea) depending on the presence of tachycardia. Anesthesia was then induced and maintained with propofol (induction 6 mg/kg, intravenous administration; maintenance 0.4 mg/kg; Handok, Korea). After anesthesia induction, venotomy was performed on the left jugular vein with a surgical blade. A fixed core wire guide (curved; Cook Medical, USA) was inserted into the vein and down into the right atrium, right ventricle, and pulmonary artery. An introducer sheath (Flexor Tuohy-Borst Sidearm Introducer; 6-8 Fr according to the size of dog; Cook Medical, USA) was inserted to the left external jugular vein guided by the pre-placed guide wire into the right atrium, right ventricle, and the pulmonary artery (Fig. 1A). The guide wire was then removed from the jugular vein. The basket device (disposable fold angular basket; working width 15~30 mm, tube diameter 1.8~2.4 mm according to the size of dog; Wilson Instruments, USA) was inserted into the introducer and spread-folded to catch heartworms under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 1). The procedure was paused for 3~4 heart beats between each attempt to extract the worms. The operation was repeated until no worms were visible by echocardiography.

Fig. 1.

Heartworm removal procedure. After induce surgical anesthesia, the left jugular vein was exposed. An introducer sheath was inserted into the left external jugular vein guided by the pre-placed guide wire into the right atrium, right ventricle, and pulmonary artery (A). The basket device was inserted into the introducer and spread-folded to catch heartworms under fluoroscopic guidance (B and C).

The first dog had 39 heartworms removed from the right cardiac chamber and pulmonary artery after five attempts. After heartworm removal, the dog was treated with prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg, BID, PO), doxycycline (5 mg/kg, BID, PO), and clopidogrel clopidogrel (2 mg/kg, SID, PO) for a week. Physical examination was performed 1 week post-heartworm removal. Clinical factors showed marked improvement; no detectible murmurs, hemoglobinuria, or worms were detected by echocardiography (Fig. 2D). This dog was treated with two doses of immiticide (melarsomine, 2.5 mg/kg; Merial, USA) with regular heartworm prevention medication (Revolution; Pfizer, USA) after heartworm removal in order to treat either residual or future microfilaria infection. This dog was also treated with ramipril (0.25 mg/kg, SID, PO; Intervet, USA) for degenerative mitral valve disease.

The second case was a 9-year-old castrated Cocker spaniel (body weight 16.4 kg). Thoracic radiography revealed generalized cardiomegaly, moderate left and right atrial and ventricular enlargement, interstitial pattern in the caudal lung lobe, and loss of abdominal detail (due to ascites). Echocardiography showed visible heartworms in right atrium and ventricle, severe tricuspid regurgitant (4.8 m/sec), mild pulmonic regurgitant (2.9 m/sec), and marked right cardiac enlargement. In addition, this dog also had chronic mitral valve insufficiency with IIIa International Small Animal Cardiac Health Council (ISACHC) grade heart failure (mitral regurgitation, peak velocity 5.0 m/sec). Prior to the heartworm removal operation, 2.2 L of ascitic fluids were removed from this dog. After preoperative medications were administered as described in Case 1 along with furosemide (4 mg/kg, intravenous administration; Handok, Korea), 17 heartworms were removed from the right cardiac chambers after five attempts (Fig. 2C). Due to the risk of cardiac arrest from pre-existing cardiac disease (i.e. chronic mitral valvular insufficiency), heartworm removal from the pulmonary arteries was not attempted. After heartworm removal, the dog was treated as Case 1.

The third case was an elderly intact mixed female dog (age was unknown since this dog was adopted, body weight 5.7 kg) presenting pale mucous membrane, hemoglobinuria, and a cough. Diagnostic imaging studies revealed caval syndrome with mild pulmonary hypertension (peak velocity of tricuspid regurgitant 2.92 m/sec) and mitral valve insufficiency with ISACHC II heart failure. Because this dog was severely anemic (packed cell volume 15%, reference range 37~55%), whole blood transfusion was performed to treat the severe anemia along with diuretic therapy to alleviate left atrial congestion (furosemide, 2 mg/kg, intravenously administered). 18 heartworms were removed from the right cardiac chambers from 4 trials of retrieval.

The fourth case was an 11-year-old intact male Yorkshire terrier (body weight 6.5 kg). Thoracic radiography revealed a right-sided cardiac enlargement (reverse 'D') with marked dilation of the pulmonary artery along with tortuous and pruned right and left pulmonary arteries with increased density in the lung fields. In addition to cardiac problems, this dog also had a collapsed trachea. Echocardiography showed a heavy heartworm infestation in the right atrium, right ventricle, and pulmonary artery. Spectral Doppler echocardiography revealed mild pulmonary hypertension (pulmonic regurgitant velocity 2.4 m/sec, tricuspid regurgitant velocity 3.0 m/sec). With this procedure, 12 heartworms (five females and seven males) were removed from the right atrium and right ventricle.

Basket retrieval devices were originally developed to remove foreign bodies from the esophagus and stomach, or stones from the urinary tract [4]. Since basket devices do not have sharp grasping claws and cannot grasp the worms, these devices rarely cause intra-cardiac or vascular damage. Furthermore, basket devices can dramatically increase the number of worms captured per retrieval because they work by capturing the worms instead of grasping them. In our study, most worms in the right cardiac chambers were efficiently removed after 3~4 times attempts. In addition, the majority of worms that migrated to the right cardiac chambers were often tangled together so that 5~10 worms could be removed in a single attempt.

Unlike the Ishihara forceps, basket devices do not have manipulating aids for placing the tip of the retrieval device. Therefore, heartworms residing in pulmonary arteries cannot be efficiently removed with a basket device. We circumvented this problem by developing a catheter-guided basket removal method. In this study, we demonstrated the use of this technique by treating four dogs with caval syndrome. Using a pre-placed large-bore vascular catheter, we were able to accurately guide the basket device to any location where heartworms were found. The basket device was easy to manipulate and guide because it was inserted into the pre-placed vascular catheter. We also found that this method caused minimal damage to the intra-cardiac structures and thus reduced bleeding due to heartworm removal via the jugular veins.

Although we did not observe complications associated with rapid antigen release in response to heartworm maceration by basket removal, possibly caused by firm closure of the basket especially if only 1~2 worms are captured at a time. Therefore, as a precautionary measure, we pre-treated all dogs with anti-inflammatory medication (prednisolone). Another concern was the potential risk of thromboembolism development due to the frequent basket retrieval attempts or accidental heartworm maceration. Consequently, we also pre-treated all dogs with anticoagulant medication (clopidogrel). Additionally, doxycycline was administered to prevent possible complications from Wolbachia spp. released from dead worms.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a common complication associated with caval syndrome and was observed in three of the four cases in this study. Post-operative examination showed PAH was remarkably decreased after worm removal without PAH-specific treatment. PAH may persist after worm removal as seen in a more recent case (unpublished data), and we did observe a incidence of persistent PAH after worm removal in the present study. However, this was due to a long-standing pulmonary complication which was treated with sildenafil (1 mg/kg, T10, P0; Pfizer, USA). This treatment was very effective for controlling PAH-related clinical signs (e.g. ascites). Other clinical signs associated with caval syndrome (e.g. anemia, hemoglobinuria, and ascites) also improved significantly after worm removal. Further medical treatment for alleviating clinical signs was not necessary for these cases. However, all dogs were also given two doses of immiticide to prevent potential residual infection after basket removal.

In summary, this new technique can improve the efficiency and safety of heartworm removal from dogs with a heavy worm burden.

References

- 1.Arita N, Yamane I, Takemura N. Comparison of canine heartworm removal rates using flexible alligator forceps guided by transesophageal echocardiography and fluoroscopy. J Vet Med Sci. 2003;65:259–261. doi: 10.1292/jvms.65.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkins C. Canine heartworm disease. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 6th ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2005. pp. 1118–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kittleson MD. Heartworm infestation and disease (dirofilariasis) In: Kittleson MD, Kienle RD, editors. Small Animal Cardiovascular Medicine. 1st ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998. pp. 370–401. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salimi N, Mahajan A, Don J, Schwartz B. A novel stone retrieval basket for more efficient lithotripsy procedures. J Med Eng Technol. 2009;33:142–150. doi: 10.1080/03091900801945176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]