Abstract

Background

The management of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) can present a challenge. The utility of upper endoscopy (esophagogastroduodenoscopy, EGD) and endoscopic therapy must be weighed against safety considerations.

Aim

To assess the utility and safety of EGD in patients with UGIB and AMI.

Methods

Using decision analysis, patients with UGIB and AMI were assigned to one of two strategies: (1) EGD prior to cardiac catheterization (EGD strategy) and (2) cardiac catheterization without EGD (CATH strategy).

Results

In patients with overt UGIB, the EGD strategy resulted in 97 deaths per 10,000 patients, compared with 600 deaths in the CATH strategy. The EGD strategy resulted in fewer non-fatal complications (1,271 vs. 6,000 per 10,000 patients). In patients with occult blood loss, the EGD strategy resulted in more deaths (59 vs. 16 per 10,000) and more non-fatal complications (888 vs. 160 per 10,000) than the CATH strategy.

Conclusions

Our analysis supports EGD prior to cardiac catheterization in patients with AMI and overt UGIB. This strategy results in fewer deaths and complications compared with a strategy of proceeding directly to catheterization. Our analysis does not support routine EGD prior to cardiac catheterization in patients with fecal occult blood.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal bleeding, Acute myocardial infarction, Gastrointestinal endoscopy, Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a first-line therapy for individuals with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) due to plaque rupture and coronary arterial thrombosis. The inhibition of platelet aggregation through the use of aspirin, clopidogrel, and/or glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, as well as anticoagulation with unfractionated or low molecular weight heparin, are important components of peri- and post-PCI adjuvant therapy.

In this context, up to 7% of patients may experience major hemorrhage following PCI [1]. While the majority of these episodes are due to hemorrhage at vascular access sites [2], gastrointestinal bleeding occurs in approximately 2% of patients who undergo primary PCI [2, 3]. Nosocomial gastrointestinal bleeding following PCI is associated with increased risk for both in-hospital and short-term mortality [3].

A clinical dilemma may arise when a patient presents with AMI and evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding prior to PCI. In this setting, clinicians must consider whether to proceed directly to cardiac catheterization and PCI or to perform endoscopic evaluation prior to cardiac catheterization. Factors that must be considered in this decision include the following: (1) the urgency of cardiac catheterization (ST-elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI] versus non ST-elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI]); (2) the likelihood of clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding on aggressive antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy; (3) the safety of endoscopy in a patient with AMI awaiting PCI; and (4) the ability of endoscopy to both identify a bleeding source and either deliver therapy that will alter the natural history of re-bleeding or provide information that will alter subsequent cardiac management.

The published literature concerning the safety and efficacy of endoscopy in patients with AMI and gastrointestinal bleeding consists largely of retrospective studies. The aim of this study was to perform a decision analysis to compare two strategies: performing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) prior to cardiac catheterization (EGD strategy) versus proceeding directly to cardiac catheterization (CATH strategy) in patients with AMI and suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB).

Methods

A decision-analytic model was constructed to compare the outcomes of the EGD strategy versus the CATH strategy. The primary outcome of the analysis was the frequency of death. Simulated patients could die from either nosocomial UGIB or EGD complications.

Secondary endpoints included the frequency of recurrent or ongoing UGIB, the frequency of EGD complications, and the frequency of combined complications (defined as recurrent UGIB or EGD complication). The time horizon for the model was the simulated patient’s length of hospital stay.

Model Structure

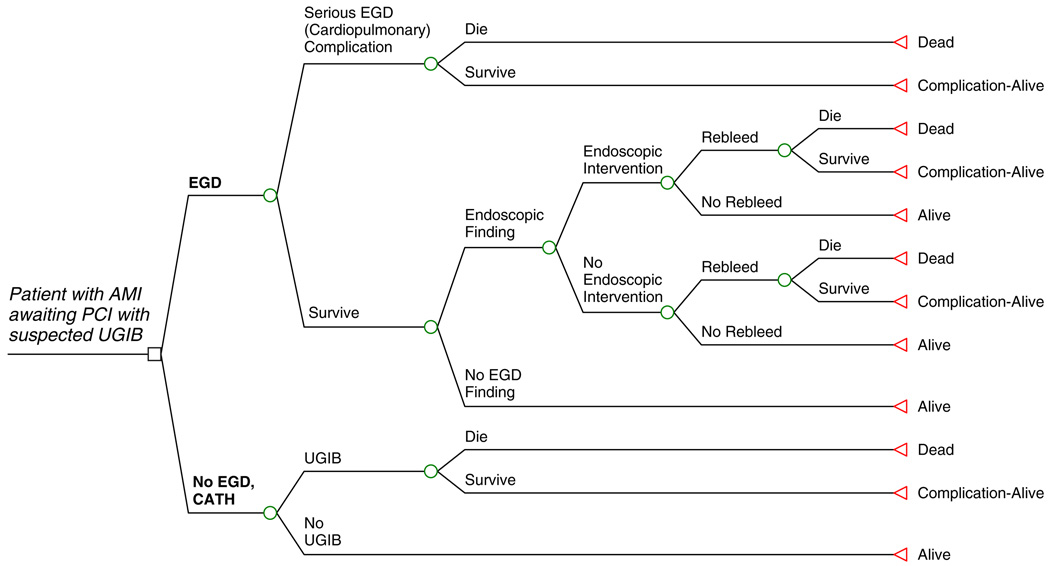

Figure 1 shows a schematic of the model. Patients presenting with AMI and suspected UGIB could either undergo EGD prior to cardiac catheterization (EGD strategy) or forego EGD and proceed directly to cardiac catheterization (CATH strategy). In the EGD strategy, simulated patients were at risk for both fatal and non-fatal serious EGD complications. For patients undergoing EGD without complication, endoscopic therapeutic intervention was predicated from the presence or absence of an identified bleeding source. Patients in whom no EGD bleeding source was identified were assumed to not be at risk for UGIB or death due to UGIB. Patients in whom an EGD bleeding source was identified were eligible for endoscopic therapeutic intervention. In addition, patients undergoing EGD were at risk for re-bleeding and death from re-bleeding, irrespective of whether endoscopic therapy had been performed or not.

Fig. 1.

A simulated patient with AMI awaiting PCI with suspected UGIB enters the schematic and proceeds to either EGD (EGD strategy) or No EGD, CATH (CATH strategy). The simulated patient then proceeds through the model, from left to right in the schematic with branch points as indicated, until a model endpoint is reached (Dead, Alive, or Complication-Alive)

In the CATH strategy, patients who developed UGIB were at risk for nosocomial death due to UGIB. Patients who did not develop UGIB were assumed to survive until discharge. In total, death among patients undergoing EGD could be caused by EGD complication or re-bleeding following EGD with or without endoscopic intervention; death among patients not undergoing EGD (CATH strategy) was due solely to nosocomial UGIB.

Employing this model structure (Fig. 1), two analyses were performed based on two distinct hypothetical patients. In Analysis 1, the simulated patient is an individual presenting with AMI awaiting PCI, and with evidence of overt UGIB, as manifested by hematemesis, melena, and/or bloody nasogastric tube aspirate [OVERT]. In Analysis 2, the simulated patient is an individual presenting with AMI awaiting PCI, and who is found to be fecal occult blood positive [OCCULT].

Patients were assumed to have no underlying or preexisting coagulopathy, no prior history of UGIB, and no underlying medical conditions that portend an increased risk for UGIB. All patients were assumed to receive gastric acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) upon initial presentation.

A commercially available software package (TreeAge Pro 2005 Suite; TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA) was used to create and run simulations on the model.

Model Inputs

The model parameters were based on estimates from the published literature. A PubMed search was performed in order to identify studies related to gastrointestinal bleeding in AMI, gastrointestinal endoscopy in AMI, and EGD findings and therapy in both overt UGIB and occult gastrointestinal blood loss. Publications in abstract form were eligible for inclusion as model inputs. The base-case values are summarized in Table 1, along with the references. In all cases in which more than one study was used to generate an estimate, the full range of estimates is provided. The point estimate used for the analysis was calculated as a mean value from the pooled outcomes of the cited studies.

Table 1.

Model inputs

| Parameter | Estimate/range | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Safety of EGD | ||

| EGD complication rate, recent AMI | 8% (7.5–8%) | Cappell and Iacovone [4], Mumtaz et al. [6] |

| EGD fatality rate, recent AMI | 0.5% (0–1%) | Cappell and Iacovone [4], Lin et al. [5], Mumtaz et al. [6] |

| EGD bleeding source identified | ||

| AMI with hematemesis, melena, or bloody NG aspirate | 92.5% (92–95%) | Cappell and Iacovone [4], Cappell [7] |

| Any patient with occult/guaiac + stool | 24% (16–36%) | Zuckerman and Benitez [23], Rockey et al. [24], Ali et al. [25], Stray and Weberg [26] |

| EGD therapeutic intervention | ||

| AMI with hematemesis or melena | 39% (34–48%) | Lin et al. [5] |

| AMI with occult/guaiac+ | 4% | Lin et al. [5] |

| Re-bleeding rate | ||

| PPI use alone (high-risk lesion) | 21%a (11–34%) | Khuroo et al. [17], Jung et al. [18], Bleau et al. [19], Bini and Cohen [20] |

| Following endoscopic therapy (high-risk lesion) | 9% (5–24%) | Bianco et al. [8], Chung et al. [9], Chua et al. [10], Saltzman et al. [11], Park et al. [12], Lo et al. [13] |

| No endoscopic therapy (low-risk lesion) | 3% (0–5%) | Lau et al. [14], Lai et al. [15], Hsu et al. [16] |

| In-hospital mortality | ||

| GI bleeding post-PCI | 10% (10–11%) | Abbas et al. [3], Lin et al. [5] |

| Incidence of UGIB following PCI | 1.6% (1–2%) | Kinnaird et al. [2], Abbas et al. [3] |

As described in the methods section, this estimate was multiplied by a factor of 3, resulting in a base-case estimate of 60% for the UGIB rate in the CATH arm

EGD complication and death rates were estimated from studies reporting the performance of EGD in patients who had suffered AMI within 30 days prior to EGD [4–6]. Possible complications included hypotension, arrhythmia, oxygen desaturation, requirement for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, angina or post-procedural myocardial infarction, and gastrointestinal perforation.

AMI was defined in these studies on the basis of serum biomarker evidence [4, 5], as well as cardiology consultation [4]. The analysis does not distinguish between STEMI or NSTEMI, as the published literature does not distinguish between endoscopy findings and complications in these two groups. There are neither retrospective nor prospective data that specifically address the safety of EGD restricted to a cohort of patients with AMI and suspected plaque rupture awaiting PCI.

Death due to nosocomial gastrointestinal bleeding in patients presenting with AMI was based on estimates from retrospective studies in the published literature [3, 5]. For the purposes of this model, mortality rates were assumed to be equivalent for UGIB following cardiac catheterization, UGIB following EGD and medical therapy, and UGIB following EGD and endoscopic therapy.

In the case of the simulated patient with overt UGIB [OVERT], the estimate for the endoscopic identification of a bleeding source was similarly identified from the published literature. Studies have reported the diagnostic yield of EGD in patients with AMI and evidence of UGIB as manifested by hematemesis [4], melena [4], or bloody nasogastric aspirate [7]. A single study by Lin et al. was used to estimate the percentage of patients with AMI and either hematemesis and/or melena who would be eligible for endoscopic therapy based on EGD findings [5]—although this estimate does not distinguish between patients presenting with AMI as the inciting event or patients presenting with gastrointestinal bleeding followed by secondary myocardial infarction [5].

For the purposes of the analysis, an endoscopic finding appropriate for endoscopic therapy was assumed to be a peptic ulcer with high-risk stigmata for re-bleeding (active bleeding, visible vessel, or adherent clot). While acknowledging that other lesions may be identified as bleeding sources eligible for endoscopic therapy, peptic ulcer disease was selected for the model because of the availability of well-established data regarding natural history and re-bleeding risk, both with [8–13] and without [14–20] endoscopic therapy. In addition, peptic ulcers represent the most commonly identified UGIB source in patients taking NSAIDs and/or anticoagulants [21].

Endoscopic therapy was defined as either epinephrine injection or multipolar coagulation, followed by hemostatic clip placement. Published re-bleeding rates in patients with ulcers and high-risk stigmata treated with combination endoscopic therapy, including hemostatic clip placement, were used to estimate the re-bleeding rate following therapeutic intervention [8–13].

An endoscopic finding identified as a bleeding source but not requiring endoscopic therapy was defined as a clean-based peptic ulcer. Re-bleeding rates for clean-based peptic ulcers were estimated from the published literature [14–16].

For patients with overt UGIB undergoing CATH alone, the rate of ongoing UGIB was defined as a product of two estimates. Re-bleeding rates for peptic ulcers with high-risk stigmata treated with PPI alone (and no endoscopic therapy) were determined from the published literature [17–20]. This pooled estimate was multiplied by a factor of three, based on a single-study estimate of the magnitude of the effect of aspirin or NSAID therapy on early ulcer re-bleeding [22].

In the case of the simulated patient with occult gastrointestinal blood loss, the frequency of endoscopic findings was based on published literature estimates of the diagnostic yield of EGD in identifying a bleeding source in patients with fecal occult blood loss [23–26]. Suitable estimates of the diagnostic yield of EGD in a cohort restricted to recent AMI and fecal occult blood could not be identified in the published literature. The frequency of endoscopic therapy in the EGD arm of the OCCULT Analysis was based on the study by Lin et al. reporting the yield of EGD in patients with UGIB, AMI, and occult bleeding [5].

As in the OVERT Analysis, endoscopic therapy was assumed to consist of combination endoscopic therapy (epinephrine injection plus either multipolar coagulation or hemostatic clip placement) of a peptic ulcer with high-risk stigmata. Re-bleeding following EGD was assumed to be due to recurrent peptic ulcer hemorrhage [8–13]. Re-bleeding following EGD without intervention was assumed to be due to a peptic ulcer with low-risk stigmata [14–16].

In the CATH arm of the OCCULT Analysis, the UGIB rate in a patient with AMI and occult bleeding was based on estimates of the nosocomial gastrointestinal bleeding rate in all patients with AMI undergoing PCI [2, 3]. Estimates of the frequency with which occult bleeding represents a risk for overt bleeding or the frequency with which antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy unmasks overt bleeding in a patient with occult bleeding could not be identified in the published literature.

Analyses Performed

A base-case analysis using the best estimates for the model parameters (Table 1) was performed. Sensitivity analyses were then performed on key model parameters, including EGD complication rate, EGD intervention rate, re-bleeding rate both with and without endoscopic therapy, mortality rate due to UGIB, and UGIB rate in the CATH arm (without EGD). If the model results were sensitive to any of the parameters, values were calculated for the thresh-old(s) at which the model’s prediction changed.

Results

Base-Case Analysis

The results of the base-case analyses are presented in Table 2. The results are presented as numbers out of a hypothetical cohort of 10,000 patients for each strategy (EGD or CATH).

Table 2.

Results of the base-case analyses

| EGD | CATH | Difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis 1 (OVERT) | |||

| Deaths | 97 | 600 | −503 (5) |

| UGIB (recurrent or ongoing) | 471 | 6,000 | −5,529 (55) |

| EGD complications | 800 | 0 | 800 (8) |

| UGIB/EGD complications combined | 1,271 | 6,000 | −4,729 (47) |

| Analysis 2 (OCCULT) | |||

| Deaths | 59 | 16 | 43 (0.4) |

| UGIB (recurrent or ongoing) | 88 | 160 | −72 (0.7) |

| EGD complications | 800 | 0 | 800 (8) |

| UGIB/EGD complications combined | 888 | 160 | 728 (7) |

All results are the number of patients out of 10,000 patients in each strategy

In a cohort of 10,000 patients with AMI awaiting PCI and overt UGIB [OVERT], the EGD strategy would result in 97 deaths due to an EGD complication or UGIB, as compared with 600 deaths due to UGIB in the CATH strategy. This represents a net difference of 503 deaths out of 10,000 patients, or 5%. Eight hundred patients would suffer EGD complications in the EGD strategy, compared with none in the CATH strategy. However, this would be more than offset in the total number of combined complications by the reduction in the number of UGIB, 471 in the EGD strategy and 6,000 in the CATH strategy (55% net difference).

Alternatively, in a cohort of 10,000 patients with AMI awaiting PCI and occult gastrointestinal bleeding [OCCULT], the EGD strategy would result in 59 deaths due to EGD complication or UGIB, as compared with 16 deaths due to UGIB in the CATH strategy. This represents a 0.43% net difference. One hundred and sixty out of 10,000 patients in the CATH strategy would experience recurrent or ongoing UGIB, as compared with 88 out of 10,000 patients in the EGD strategy. However, the combined number of complications would be higher in the EGD strategy (888 vs. 160), driven largely by the 8% incidence of EGD complications.

Sensitivity Analysis

The results of the sensitivity analyses are depicted in Table 3 and Table 4. Sensitivity analyses for patients with OVERT UGIB are presented in Table 3, while sensitivity analyses for patients with OCCULT UGIB are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses, patient with OVERT UGIB

| Parameter | EGD |

CATH |

Difference |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | UGIB | EGD complications |

Combined complications |

Death | UGIB | EGD complications |

Combined complications |

Death (%) | Combined complications |

|

| EGD complication | ||||||||||

| (Base 8%) | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −503 (5) | −4,729 (47) |

| 1% | 57 | 506 | 100 | 606 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −94 (1) | −5,394 (54) |

| 16% | 143 | 430 | 1,600 | 2,030 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −170 (2) | −3,970 (40) |

| 32% | 235 | 348 | 3,200 | 3,548 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −252 (3) | −2,452 (25) |

| 58% | 384 | 215 | 5,800 | 6,015 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −385 (4) | 15 (0.2) |

| EGD source ID | ||||||||||

| (Base 92.5%) | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −503 (5) | −4,729 (47) |

| 80% | 91 | 407 | 800 | 1,207 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −509 (5) | −4,793 (48) |

| 100% | 101 | 509 | 800 | 1,309 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −499 (5) | −4,691 (47) |

| EGD intervention | ||||||||||

| (Base 39%) | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −503 (5) | −4,729 (47) |

| 20% | 86 | 363 | 800 | 1,163 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −514 (5) | −4,837 (48) |

| 78% | 119 | 686 | 800 | 1,486 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −481 (5) | −4,514 (45) |

| Death due to UGIB | ||||||||||

| (Base 10%) | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −503 (5) | −4,729 (47) |

| 1% | 55 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 60 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −5 (0.05) | −4,729 (47) |

| 20% | 144 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 1,200 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −1,056 (11) | −4,729 (47) |

| Rebleeding rate | ||||||||||

| (Base 9%, 3%) | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 60 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | 37 (0.4) | −4,729 (47) |

| 4.5%, 1.5% | 74 | 235 | 800 | 1,035 | 60 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | 14 (0.1) | −4,965 (50) |

| 18%, 6% | 144 | 941 | 800 | 1,741 | 60 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | 84 (0.8) | −4,259 (43) |

| UGIB rate if no EGD performed | ||||||||||

| (Base 60%) | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 600 | 6,000 | 0 | 6,000 | −503 (5) | −4,729 (47) |

| 5% | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 50 | 500 | 0 | 500 | 47 (0.4) | 771 (8) |

| 9.5% | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 97 | 970 | 0 | 970 | 0 | 301 (3) |

| 10% | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 100 | 1,000 | 0 | 1,000 | −3 (0.03) | 271 (3) |

| 12.7% | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 127 | 1,270 | 0 | 1,270 | −30 (0.3) | 1 (0.01) |

| 30% | 97 | 471 | 800 | 1,271 | 300 | 3,000 | 0 | 3,000 | −203 (2) | −1,729 (17) |

All results are the number of patients out of 10,000 patients in each strategy

Threshold values are highlighted in bold type

Table 4.

Sensitivity analyses, patient with OCCULT blood loss

| Parameter | EGD |

CATH |

Difference |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | UGIB | EGD complications |

Combined complications |

Death | UGIB | EGD complications |

Combined complications |

Death (%) | Combined complications |

|

| EGD complication | ||||||||||

| (Base 8%) | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 43 (0.4) | 728 (7) |

| 0.67 | 14 | 95 | 67 | 162 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | −2 (0.02) | 2 (0.02) |

| 0.8% | 15 | 95 | 80 | 175 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | −1 (0.01) | 15 (0.2) |

| 1% | 16 | 95 | 100 | 195 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 0 | 35 (0.4) |

| 16% | 108 | 81 | 1,600 | 1,681 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 92 (0.9) | 1,521 (15) |

| EGD source ID | ||||||||||

| (Base 24%) | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 43 (0.4) | 728 (7) |

| 6% | 52 | 22 | 800 | 822 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 36 (0.4) | 662 (7) |

| 12% | 54 | 44 | 800 | 844 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 38 (0.4) | 684 (7) |

| 36% | 63 | 133 | 800 | 933 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 47 (0.5) | 773 (8) |

| EGD intervention | ||||||||||

| (Base 4%) | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 43 (0.4) | 728 (7) |

| 1% | 57 | 72 | 800 | 872 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 41 (0.4) | 712 (7) |

| 20% | 68 | 177 | 800 | 977 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 52 (0.5) | 817 (8) |

| Death due to UGIB | ||||||||||

| (Base 10%) | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 43 (0.4) | 728 (7) |

| 1% | 51 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 2 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 49 (0.5) | 728 (7) |

| 20% | 68 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 32 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 36 (0.4) | 728 (7) |

| Rebleeding rate | ||||||||||

| (Base 9%, 3%) | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 43 (0.4) | 728 (7) |

| 4.5%, 1.5% | 54 | 44 | 800 | 844 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 38 (0.4) | 684 (7) |

| 18%, 6% | 68 | 177 | 800 | 977 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 52 (0.5) | 817 (8) |

| UGIB rate if no EGD performed | ||||||||||

| (Base 1.6%) | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 16 | 160 | 0 | 160 | 43 (0.4) | 728 (7) |

| 3% | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 30 | 300 | 0 | 300 | 29 (0.3) | 588 (6) |

| 5.9% | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 59 | 590 | 0 | 590 | 0 | 298 (3) |

| 8.9% | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 89 | 890 | 0 | 890 | −30 (0.3) | −2 (0.02) |

| 15% | 59 | 88 | 800 | 888 | 150 | 1,500 | 0 | 1,500 | −91 (0.9) | −612 (6) |

All results are the number of patients out of 10,000 patients in each strategy

Threshold values are highlighted in bold type

Recall that in the base-case analysis, EGD prior to cardiac catheterization was the preferred strategy for patients with OVERT UGIB. However, the model was sensitive to three parameter estimates or variables. If the EGD complication rate is 58% or higher (more than 7-fold above our base-case estimate), the EGD strategy results in more combined complications than the CATH strategy (Table 3). If the mortality rate due to UGIB is below 1% (10-fold lower than our base-case estimate), then there is no mortality benefit in the EGD strategy (Table 3). CATH (without EGD) also becomes a preferred strategy to EGD prior to cardiac catheterization only at low estimates of the UGIB rate in the CATH arm—there is no mortality difference in the two strategies at a 9.5% UGIB rate, and no difference in the overall complication rate of the two strategies at a 12.7% UGIB rate (Table 3).

In patients with OCCULT UGIB, proceeding directly to cardiac catheterization without EGD was the preferred strategy in the base-case analysis. However, this model was sensitive to two parameter estimates. The EGD strategy becomes a preferred strategy if EGD complication rates are below 1%, which is 8-fold below our base-case estimate (Table 4). Similarly, EGD becomes a preferred strategy with higher estimates of the UGIB rate in the CATH arm: at a 5.9% UGIB rate, 59 deaths are expected out of 10,000 patients in each arm; at a 8.9% UGIB rate, approximately 890 combined complications are expected in each arm (Table 4).

Table 5 summarizes the key parameter estimates, with threshold values, for the sensitivity analyses.

Table 5.

Key parameter estimates in sensitivity analyses

| Notes | |

|---|---|

| Patients with AMI and overt UGIB | |

| Strategy of proceeding directly to CATH preferred if: | |

| EGD complication rate is ≥58% | |

| UGIB mortality rate is <1% | |

| UGIB rate following CATH is <12.7% | No difference in complication rate between EGD and CATH strategies |

| UGIB rate following CATH is <9.5% | No difference in mortality rate between EGD and CATH strategies |

| Patients with AMI and occult UGIB | |

| Strategy of EGD prior to CATH preferred if: | |

| EGD complication rate is <1% | |

| UGIB rate following CATH is >5.7% | No difference in mortality rate between EGD and CATH strategies |

| UGIB rate following CATH is >8.9% | No difference in complication rate between EGD and CATH strategies |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare two management strategies in patients with AMI and suspected UGIB: performing EGD prior to cardiac catheterization versus proceeding directly to cardiac catheterization.

Our model supports the performance of EGD prior to CATH in patients with overt UGIB. This strategy results in fewer deaths and a lower incidence of ongoing or recurrent UGIB in a hypothetical cohort of patients when compared with a strategy of foregoing EGD and proceeding directly to cardiac catheterization. Alternatively, for patients in whom UGIB is suspected only on the basis of fecal occult blood, EGD prior to CATH results in a greater number of nosocomial deaths and a higher overall complication rate when compared with a strategy of proceeding directly to cardiac catheterization.

At first glance, the results of this decision analysis may seem intuitive. Patients with overt UGIB as manifested by hematemesis and/or melena are patients in whom EGD is likely to demonstrate active bleeding or lesions with high-risk stigmata, and in whom endoscopic therapy is most likely to alter the natural history of re-bleeding and, thereby, positively impact patient outcomes. Alternatively, patients with occult UGIB may be less likely to have high-risk lesions and less likely to require endoscopic therapy, and may be best managed through supportive care with respect to bleeding and direct attention to the underlying cardiac illness.

On the other hand, clinical management decisions may be complex in a patient presenting simultaneously with multiple acute medical illnesses, including AMI and UGIB. A decision analysis model, using base-case as well as varying estimates of outcomes and risks, can provide a rational framework for discriminating between competing management strategies. Decision analysis can be an effective tool to support and inform clinical decisions based on best available data, particularly in instances when controlled prospective data are unavailable. A randomized controlled study of an EGD versus CATH strategy in patients with AMI and UGIB is not likely to ever be performed due to ethical and logistical considerations.

Among patients with epicardial coronary disease undergoing endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract, up to 16% will demonstrate electrocardiographic evidence of myocardial ischemia peri-procedure [27]. Some of these episodes of ischemia may not result in clinically demonstrable consequences. Arrhythmia, hypotension, or respiratory compromise during EGD may be immediately reversible following cessation of the procedure. Nonetheless, endoscopic evaluation carries a higher than average risk in patients with recent AMI.

Mortality rates as high as 1% have been reported in patients with recent AMI undergoing EGD [5]. This is higher than the 0.1% mortality rate reported for patients undergoing EGD for the evaluation of gastrointestinal hemorrhage [28] and several log-fold higher than the baseline 0.0004% mortality rate of EGD [29].

The decision of whether to perform EGD in a patient with recent AMI must consider these factors against the potential diagnostic and therapeutic yield of EGD. A bleeding source can be identified by EGD in more than 90% of AMI patients with hematemesis, melena, or bloody nasogastric aspirate [4, 7]. Our model assumes that peptic ulcer disease is identified as the culprit lesion in patients with overt UGIB. Clear data exist to support the benefit of combined endoscopic and medical therapy in reducing the likelihood of re-bleeding in patients with peptic ulcers and high-risk stigmata.

Lesions other than peptic ulcers, such as gastritis and esophagitis, may result in UGIB and, in fact, may be the predominant EGD finding in hospitalized patients with UGIB episodes not associated with hemodynamic changes or transfusion requirement [30]. Given their diffuse nature, such lesions, typically, are not amenable to endoscopic therapy. Nevertheless, independent of endoscopic therapy, EGD findings may impact subsequent management decisions, including the timing of cardiac catheterization, in approximately 40% of patients with AMI and UGIB [5, 6].

The timing and urgency of cardiac catheterization may be similarly influenced by whether an individual patient has sustained STEMI or NSTEMI, and our model does not distinguish between these two scenarios. EGD diagnosis and therapy are most likely to be beneficial in scenarios when delayed cardiac catheterization is an option, as the likelihood of peptic ulcer re-bleeding, for instance, dramatically decreases after 72 h [31]. This decision analysis may, therefore, be more relevant to patients with NSTEMI, in whom early versus delayed revascularization may be considered, as opposed to patients with STEMI, for whom guidelines advocate PCI within 90 min of hospital presentation [32].

The validity of a decision-analysis model is predicated on the validity of the clinical assumptions inherent in the model. One critical assumption in our model is the extent to which antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy peri-PCI impacts post-procedural UGIB. Platelet aggregation is impaired at acidic gastric pH [33]. In addition, mucosal fibrinolytic activity following peptic ulcer hemorrhage may be mitigated by effective acid suppression [34]. Raising the gastric pH is thought to be the central mechanism by which histamine (H2) antagonists and PPIs promote ulcer healing and reduce re-bleeding rates.

Standard practice is to minimize, whenever possible, antiplatelet and anticoagulant burden following UGIB, particularly in patients with peptic ulcers containing high-risk stigmata. Aspirin increases the risk of UGIB in a dose-dependent fashion [35, 36] and the full magnitude of risk may be achieved within 30 days of initiation of therapy [36]. The addition of clopidogrel or ticlopidine to low-dose aspirin appears to have at least an additive effect on the risk of UGIB [36, 37].

However, there are limited data that assess the impact of systemic antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy on early rebleeding following acute UGIB, either with or without endoscopic therapy. A single retrospective study carried out a decade ago described a 20% rate (28/138) of UGIB in patients on aspirin and either heparin or warfarin following coronary stent placement as compared with a 0% rate (0/ 109) of UGIB in patients on aspirin alone following stent placement [38]—mean time to bleeding was 2.5 days following the initiation of therapy—yet, these were patients without known a priori UGIB. Peptic ulcers were confirmed by EGD in 25% of the patients with suspected UGIB [38].

A second critical assumption (for the OCCULT Analysis) is that fecal occult blood is a risk factor for clinically significant overt UGIB in a patient exposed to antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy. Our model assumed that patients with fecal occult blood could be found to have peptic ulcers on EGD—limited data reporting the frequency of documented peptic ulcer disease in hospitalized patients with occult or clinically insignificant blood loss present a wide range of estimates, from 1% [30] to greater than 20% [39]. Even among patients with fecal occult blood and a plausible bleeding source identified on EGD, no large-scale prospective or retrospective data exist to suggest what percentage of these patients will require specific endoscopic therapy. And while there are case reports and case series using systemic anticoagulation (even thrombolysis) and “provocative” angiography [40–42] or endoscopy [43] in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, there are no data available to quantify the risk for the transformation of occult gastrointestinal bleeding into overt, clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding due to anticoagulation.

The UGIB rate in the CATH arm of the OCCULT Analysis, therefore, represents a critical parameter estimate in our analysis. Based on a lack of compelling data to suggest a magnitude of increased risk, we assigned a 1.6% UGIB risk to these patients, a rate that is identical to the gastrointestinal bleeding rate in all patients undergoing PCI. The magnitude of overt bleeding risk in this scenario is debatable, and sensitivity analyses allow for a more speculative approach. Sensitivity analyses suggest the equivalence of the EGD and CATH strategies, beginning at an UGIB rate more than 3.5-fold higher than our base-case estimate.

In addition to antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy, patient and procedural factors influence the risk of UGIB following PCI. Patient gender, age, prior history of bleeding, and the presence of comorbidities, such as chronic kidney disease, may be associated with increased bleeding risk following PCI [44], and our model does not account for these patient variables. The incidence of post-operative gastrointestinal bleeding has been described in the cardiac surgical literature with an incidence of 1.5%, as reported in a large meta-analysis [45] (0.45% incidence for UGIB alone [46]). Procedural factors, including aortic cross-clamp and bypass time [44] and prolonged mechanical ventilation [47], are associated with UGIB following cardiac surgery.

This raises the question as to whether patients with AMI and UGIB experience hemorrhage due to traditional risk factors for UGIB and whether all patients with UGIB post-PCI would have had identifiable at-risk lesions on EGD prior to catheterization. Patient age, history of diabetes, and history of prior heart failure may all be associated with the development of UGIB in patients with acute coronary syndromes [48]. Procedural factors influencing UGIB in the PCI population include catheter laboratory complications (as defined in one study as arrhythmia, hypotension, intubation, and/or cardiopulmonary resuscitation) [3] and the use of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation [2]. Collectively, these variables may implicate ischemic injury, due either to hypoperfusion or cholesterol embolization [49, 50], as etiologic agents in some patients with UGIB following PCI.

The number of patients with concurrent AMI and UGIB will likely remain considerable, particularly in light of the considerable burden of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy employed in the treatment of AMI. When bleeding does occur, endoscopic therapy may be performed in the setting of systemic anticoagulation [51] and significant lesions may be identified, even in the context of supratherapeutic coagulopathy [52]. Coagulopathy at the time of initial bleeding and endoscopy does not appear to be associated with higher rates of re-bleeding following endoscopic therapy for nonvariceal UGIB [53].

A decision analysis model is not a substitute or surrogate for clinical judgment in individual patient circumstances. While practice in individual instances will be dictated by the relative severity of acute coronary disease and gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and the perceived vital threat of each, clinical decisions should, nonetheless, be based upon a thorough understanding of the net risks and benefits of the available options. Our analysis supports a strategy of EGD prior to cardiac catheterization in patients with AMI and overt UGIB. Such a strategy will result in fewer nosocomial deaths and complications. Our analysis does not support a strategy of routine EGD prior to cardiac catheterization for patients in whom UGIB is suspected solely on the basis of fecal occult blood. If EGD is to be pursued in these instances, the decision should be based on additional variables supporting a suspicion of clinically significant UGIB.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Marc Sabatine, MD, MPH, for his comments and suggestions on this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Patrick Yachimski, Email: pyachimski@partners.org, Blake 4 Gastrointestinal Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Chin Hur, Blake 4 Gastrointestinal Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA; Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Institute for Technology Assessment, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

References

- 1.Keeley AC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinnaird TB, Stabile E, Mintz GS, et al. Incidence, predictors, and prognostic implications of bleeding and blood transfusion following percutaneous coronary interventions. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:930–935. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00972-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbas AE, Brodie B, Dixon S, et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of gastrointestinal bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappell MS, Iacovone FM., Jr Safety and efficacy of esophagogastroduodenoscopy after myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 1999;106:29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin S, Konstance R, Jollis J, et al. The utility of upper endoscopy in patients with concomitant upper gastrointestinal bleeding and acute myocardial infarction. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2377–2383. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mumtaz K, Ismail F, Hamid S, et al. Safety and efficacy of esophagogastroduodenoscopy in acute myocardial infarction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB116. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cappell MS. Safety and efficacy of nasogastric intubation for gastrointestinal bleeding after myocardial infarction: an analysis of 125 patients at two tertiary cardiac referral hospitals. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2063–2070. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Marmo R, et al. Combined epinephrine and bipolar probe coagulation vs. bipolar probe coagulation alone for bleeding peptic ulcer: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:910–915. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung IK, Ham JS, Kim HS, et al. Comparison of the hemostatic efficacy of the endoscopic hemoclip method with hypertonic saline-epinephrine injection and a combination of the two for the management of bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70439-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua TS, Fock KM, Ng TM, et al. Epinephrine injection therapy versus a combination of epinephrine injection and endoscopic hemoclip in the treatment of bleeding ulcers. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1044–1047. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i7.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saltzman JR, Strate LL, Di Sena V, et al. Prospective trial of endoscopic clips versus combination therapy in upper GI bleeding (PROTECCT-UGI bleeding) Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1503–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park CH, Joo YE, Kim HS, et al. A prospective, randomized trial comparing mechanical methods of hemostasis plus epinephrine injection to epinephrine injection alone for bleeding peptic ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:173–179. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo CC, Hsu PI, Lo GH, et al. Comparison of hemostatic efficacy for epinephrine injection alone and injection combined with hemoclip therapy in treating high-risk bleeding ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:767–773. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau JY, Chung SC, Leung JW, et al. The evolution of stigmata of hemorrhage in bleeding peptic ulcers: a sequential endoscopic study. Endoscopy. 1998;30:513–518. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai KC, Hui WM, Wong BCY, et al. A retrospective and prospective study on the safety of discharging selected patients with duodenal ulcer bleeding on the same day as endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:26–30. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu PI, Lai KH, Lin XZ, et al. When to discharge patients with bleeding peptic ulcers: a prospective study of residual risk of rebleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:382–387. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuroo MS, Yattoo GN, Javid G, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and placebo for bleeding peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1054–1058. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung HK, Son H-Y, Jung S-A, et al. Comparison of oral omeprazole and endoscopic ethanol injection therapy for prevention of recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcers with nonbleeding visible vessels or fresh adherent clots. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1736–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bleau BL, Gostout CJ, Sherman KE, et al. Recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer associated with adherent clot: a randomized study comparing endoscopic treatment with medical therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:1–6. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bini EJ, Cohen J. Endoscopic treatment compared with medical therapy for the prevention of recurrent ulcer hemorrhage in patients with adherent clots. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:707–714. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomopoulos KC, Mimidis KP, Theocharis GJ, et al. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on long-term oral anticoagulation therapy: endoscopic findings, clinical management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1365–1368. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i9.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Godil A, DeGuzman L, Schilling RC, 3rd, et al. Recent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use increases the risk of early recurrence of bleeding in patients presenting with bleeding ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:146–151. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuckerman G, Benitez J. A prospective study of bidirectional endoscopy (colonoscopy and upper endoscopy) in the evaluation of patients with occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockey DC, Koch J, Cello JP, et al. Relative frequency of upper gastrointestinal and colonic lesions in patients with positive fecal occult-blood tests. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:153–159. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807163390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali M, Yaqub M, Haider Z, et al. Yield of dual endoscopy for positive fecal occult blood test. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:82–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stray N, Weberg R. A prospective study of same day bidirectional endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:844–850. doi: 10.1080/00365520500495789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JG, Krucoff MW, Brazer SR. Periprocedural myocardial ischemia in patients with severe symptomatic coronary artery disease undergoing endoscopy: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Med. 1995;99:270–275. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert DA, Silverstein FE, Tedesco FJ. National ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding: complications of endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:55S–59S. doi: 10.1007/BF01300808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silvis SE, Nebel O, Rogers G, et al. Endoscopic complications. Results of the 1974 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Survey. JAMA. 1976;235:928–930. doi: 10.1001/jama.235.9.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kethu SR, Davis GD, Reinert SE, et al. Low utility of endoscopy for suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding occurring in hospitalized patients. South Med J. 2005;98:170–175. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000149389.24871.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin HJ, Perng CL, Lee FY, et al. Clinical courses and predictors for rebleeding in patients with peptic ulcers and non-bleeding visible vessels: a prospective study. Gut. 1994;35:1389–1393. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.10.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1999 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:671–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green FW, Jr, Kaplan MM, Curtis LE, et al. Effect of acid and pepsin on blood coagulation and platelet aggregation. A possible contributor prolonged gastroduodenal mucosal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vreeburg EM, Levi M, Rauws EAJ, et al. Enhanced mucosal fibrinolytic activity in gastroduodenal ulcer haemorrhage and the beneficial effect of acid suppression. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:639–646. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slattery J, Warlow CP, Shorrock CJ, et al. Risks of gastrointestinal bleeding during secondary prevention of vascular events with aspirin—analysis of gastrointestinal bleeding during the UK-TIA trial. Gut. 1995;37:509–511. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanas A, García-Rodríguez LA, Arroyo MT, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal ulcer bleeding associated with selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, traditional non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and combinations. Gut. 2006;55:1731–1738. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hallas J, Dall M, Andries A, et al. Use of single and combined antithrombotic therapy and risk of serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: population based case–control study. BMJ. 2006;333:726. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38947.697558.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Younossi ZM, Strum WB, Schatz RA, et al. Effect of combined anticoagulation and low-dose aspirin treatment on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:79–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1018833021039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wroblewski M, Ostberg H. Ulcer disease among geriatric inpatients with positive faecal occult blood test and/or iron deficiency anaemia. A prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:489–495. doi: 10.3109/00365529009095520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malden ES, Hicks ME, Royal HD, et al. Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding: use of thrombolysis with anticoagulation in diagnosis. Radiology. 1998;207:147–151. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.1.9530310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bloomfield RS, Smith TP, Schneider AM, et al. Provocative angiography in patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage of obscure origin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2807–2812. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan JM, Key SM, Dumbelton SA, et al. Nonlocalized lower gastrointestinal bleeding: provocative bleeding studies with intraarterial tPA, heparin, and tolazoline. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1273–1277. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rieder F, Schneidewind A, Bolder U, et al. Use of anticoagulation during wireless capsule endoscopy for the investigation of recurrent obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2006;38:526–528. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moscucci M, Fox KAA, Cannon CP, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1815–1823. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nalysnyk L, Fahrbach K, Reynolds MW, et al. Adverse events in coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) trials: a systematic review and analysis. Heart. 2003;89:767–772. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.7.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Voort PH, Zandstra DF. Pathogenesis, risk factors, and incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after cardiac surgery: is specific prophylaxis in routine bypass procedures needed? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halm U, Halm F, Thein D, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection: a risk factor for upper gastrointestinal bleeding after cardiac surgery? Crit Care Med. 2000;28:110–113. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200001000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Mallah M, Bazari R, Jankowski M, et al. Predictors and outcomes associated with gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Throm Thrombolysis. 2007;23:51–55. doi: 10.1007/s11239-006-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moolenaar W, Lamers CB. Gastrointestinal blood loss due to cholesterol crystal embolization. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:220–223. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199510000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller FH, Kline MJ, Vanagunas AD. Detection of bleeding due to small bowel cholesterol emboli using helical CT examination in gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3623–3625. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choudari CP, Rajgopal C, Palmer KR. Acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage in anticoagulated patients: diagnoses and response to endoscopic treatment. Gut. 1994;35:464–466. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubin TA, Murdoch M, Nelson DB. Acute GI bleeding in the setting of supratherapeutic international normalized ratio in patients taking warfarin: endoscopic diagnosis, clinical management, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolf AT, Wasan SK, Saltzman JR. Impact of anticoagulation on rebleeding following endoscopic therapy for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]