Abstract

The purpose of this study is to see if financial strain affects the religious involvement and life satisfaction of older Mexican Americans. In the process, an effort was made to explore the factors that promote financial strain in this ethnic group, including immigration status and English language use. The data come from a nationwide survey of older Mexican Americans. Support was found for the following core relationships in the study model: (1) older adults who were born in Mexico will have less schooling; (2) less education will be associated with less frequent use of English; (3) less frequent use of English will be associated with greater financial strain; (4) greater financial strain leads to less formal involvement in the church; (5) older people who are less involved in the church will have a diminished sense of religious meaning; and (6) older adults with a lower sense of religious meaning will be less satisfied with life.

A number of studies suggest that ongoing financial strain is associated with poor physical (Krause, Newsom, and Rook 2008) and mental health (Lincoln 2007). As this literature began to mature, an effort was made to determine how the deleterious effects of financial strain might arise. Although a number of potentially important mechanisms were identified, a small cluster of studies suggest that financial strain operates by promoting greater social isolation from others (Mendes de Leon, Rapp and Kasl 1994). The purpose of this study is to see whether greater exposure to financial strain is associated with less involvement in the church and a diminished sense of life satisfaction. In the process, an effort is made to contribute to the literature in three potentially important ways.

First, the relationships between financial strain, involvement in the church, and well-being are studied in a ethnic group that has received far too little attention in the literature on religion and health – older Mexican Americans. In fact, there has been relatively little progress in studying the effects of religion among older Mexican Americans since the pioneering work of Levin and Markides in the 1980s (Levin and Markides 1985).

Second, an effort is made to develop a conceptual model that shows how financial difficulties arise among older Mexican Americans. Less involvement in the church figures prominently in this respect.

Third, after tracing the genesis of financial problems and linking them with limited involvement in the church, an effort is made to show how diminished contact with the church compromises feelings of life satisfaction among older Mexican Americans. A religious sense of meaning in life plays a key mediating role in this respect. The conceptual scheme that was designed to accomplish these tasks is introduced in the next section.

Financial Strain, Religion, and Life Satisfaction among Older Mexican Americans

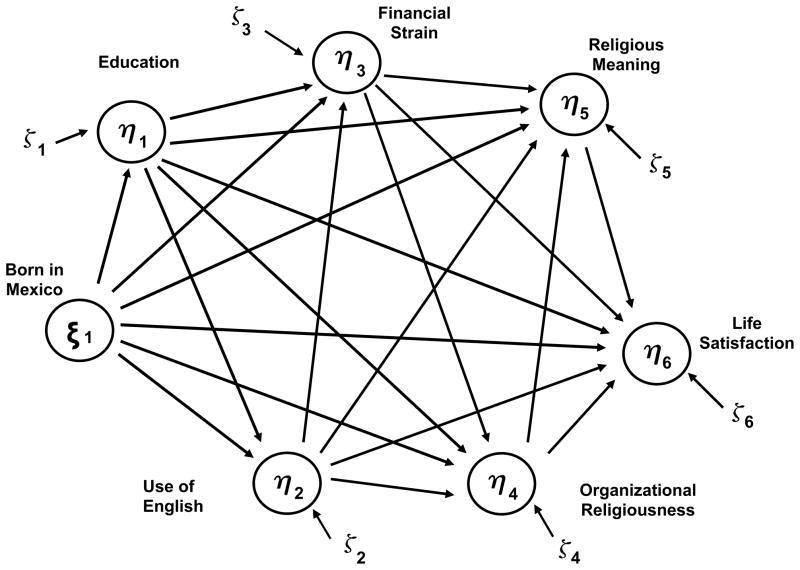

Figure 1 contains the latent variable model that is evaluated in this study. Two steps were taken to simplify the presentation of this conceptual scheme. First, the elements of the measurement model (i.e., the factor loadings and measurement error terms) are not depicted. Second, the relationships among the constructs in Figure 1 were estimated after the effects of age and gender were controlled statistically (i.e., these demographic measures served as exogenous variables).

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model of Financial Strain, Religion, and Life Satisfaction

Research indicates that the majority of older Mexican Americans immigrate to the United States from Mexico (i.e., approximately 53% – see Markides 2003). Consequently, the study of financial difficulty in this ethnic group must begin with this fact. It is for this reason that the model depicted in Figure 1 begins with place of birth. It is predicted in this conceptual scheme that (1) older adults who were born in Mexico will be less likely to speak English; (2) older Mexican Americans who do not speak English often will be more likely to encounter financial difficulties; (3) older Mexican Americans who experience more economic problems will be less involved in the church; (4) older Mexican Americans who are less involved in the church will be less likely to derive a religious sense of meaning in life; and (5) levels of life satisfaction will be lower for older Mexican Americans who have not found a strong sense of religious meaning. The theoretical rationale for these linkages is provided below. Following this, the importance of examining these issues in samples comprising older adults is discussed briefly.

Country of Birth and the Genesis of Financial Strain

There are at least four reasons why older people of Mexican ancestry who immigrate from Mexico have lower levels of educational attainment than older Mexican Americans who were born in the United States. First, the education system in Mexico is not as well developed as that of the United States and as a result, older Mexican Americans who were born in Mexico are likely to have fewer years of schooling. Second, widespread poverty in Mexico limited the ability of the people who lived there to receive a good education. Third, the labor market in Mexico does not require levels of education that are as high as those that are required in developed countries. Fourth, some immigrants settled in ethnic enclaves where the opportunity to learn English was more limited.

An individual’s level of educational attainment is important because, as Mirowsky and Ross (2003) demonstrate, the amount of schooling an individual receives has lifelong implications. One implication is examined in Figure 1. It is proposed that older Mexican Americans with fewer years of schooling are less likely to have had the opportunity to learn English. And the combination of low education and the inability to speak English makes it difficult to find a job with a good salary. Information on the occupation of the participants in this study was not obtained because only older Mexican Americans who are retired were eligible to be interviewed. Even so, as Schulz (2001) maintains, the vestiges of a poor employment history are evident in the financial status of workers after they retire. First, he shows that low status jobs rarely offer pension programs. Second, the low salaries that workers receive yield low Social Security pay-outs. Third, jobs with inadequate salaries provide little opportunity to save for retirement. Based on these insights, it is predicted in Figure 1 that low education and low English language use are associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing financial strain in retirement. Support for the notion that English usage and education are associated with economic difficulty among older Hispanics is provided by Krause and Goldenhar (1992). It is especially important to explore economic consequences of poor schooling and low English language use because research consistently shows that poverty rates are quite high among older Hispanics. More specifically, data gathered in 2007 suggest that 5% of older non-Hispanic white men lived in poverty while 13% of older Hispanic men lived below the poverty level. Similarly, these data further reveal that 9% of older non-Hispanic women experienced poverty while 20% of older Hispanic women lived in poverty (Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics 2010).

Financial Strain and Involvement in the Church

Earlier, research was reviewed which indicates that older people who experience economic problems are more socially isolated. Research reveals that this isolation arises, in part, because older people who encounter more financial strain tend to be more distrustful of others (Krause, 1993) and they are more likely to experience feelings of anger and hostility (Ross and Van Willigen 1996). These factors alone may also explain why financial strain is associated with diminished involvement in the church. But there is an additional factor that may provide further insight into this relationship. There is some evidence that congregations (but not denominations) tend to be relatively homogeneous with respect to social class (Reimer 2007). So, if an older person is experiencing financial difficulty, there is a good chance the members of his or her congregation will also be facing economic problems. The social fallout from these shared economic problems is captured by Hobfoll (1998) in his discussion of the pressure cooker effect: “Since no one in the system is free of threat, individuals who themselves have great need to depend on others must serve as supporters and lose precious resources that they themselves require at the time” (p. 208). And if Hobfoll (1998) is correct, the competition for scarce resources may potentially foster interpersonal conflict. In addition, research by Belle (1982) shows what also may happen under these circumstances. She studied the social relationships of lower class women. Belle’s (1982) research reveals that lower class women tend to withdraw from social relationships because they feel they will be unable to reciprocate when former support providers need assistance. So, in addition to avoiding church activities because of distrust, hostility, and anger, older Mexican Americans who experience financial strain may also avoid involvement in a congregation because they know they do not have the resources they would need to reciprocate for any assistance they might receive from the people who worship there and because they may encounter negative interaction arising from the scarcity of resources..

Formal Church Involvement and Religious Meaning in Life

Researchers in the social and behavioral sciences have argued for decades that people have a fundamental need to derive a sense of meaning in life. In fact, some investigators such as Frankl (1959/1985) maintain that the search for meaning “… is the primary motivation in life” (p. 121). The same notion is evident in the work of Berger (1967) who argued that there is “… a human craving for meaning that appears to have the force of instinct” (p. 22). And Maslow (1968) captured the essence of this perspective when he observed that, “The human needs a framework of values, a philosophy of life … in about the same sense that he needs sunlight, calcium, and love” (p. 206). In fact, the emphasis that Maslow placed on meaning in life became even more evident toward the end of his career. As Koltko-Rivera (2006) points out, late in his life Maslow proposed a new level of development that he placed at the top of his hierarchy of needs ahead of self-actualization. He called this new stage “self-transcendence.” Self-transcendence involves deriving a more comprehensive sense of meaning in life by moving beyond purely personal interests to more extra-personal interests that include contributing to the community and being more concerned about the welfare of others. But, perhaps, no one more forcefully argued for the central role of meaning in life than Carl Jung. He maintained that, “The least of things with a meaning is always worth more in life than the greatest of things without it” (Jacobi and Hull 1953, p. 85).

People can find meaning in a number of social settings, including work, hobbies and social relationships. However, one of the most important sources of meaning is religion. Evidence of this may be found in the classic work of Clark (1958), who argued that “… religion, more than any other human function satisfies the need for meaning in life” (p. 419). Similarly, in the process of developing his thought-provoking discussion of significance, Pargament (1997) observes that, “In essence, religion offers meaning in life” (p. 49, see also Berger 1967).

So, if one of the primary motivating forces in life is the need to find meaning, and one of the major purposes of religion is to provide a sense of meaning, then it follows that older people who are more deeply involved in the church will be more likely to derive a religious sense of meaning in life. Krause (2003) defines religious meaning as the process of turning to religion in order to find a sense of purpose in life, a sense of direction in life, and a sense that there is a reason for one’s existence.

A sense of religious meaning in life can arise from a number of sources. For example, as Krause (2008) points out, fellow church members may help an older person find a sense of meaning by reinforcing religious principles and encouraging greater involvement in the faith. However, as predicted in Figure 1, a sense of religious meaning in life can also arise from involvement in formal church activities. Two formal aspects of religious involvement are especially important in this respect. First, encouragement and guidance on how to derive a sense of meaning in life may be found in the sermons, hymns, and group prayers that typically take place during formal worship services. Second, a number of congregations offer formal Bible study groups. Many passages in the Bible are subtle, some are difficult to understand, and others may be interpreted in more than one way. One of the primary functions of Bible study groups is to help people work through these challenges (Wink 2004). The Bible is the official sacred document of the faith. If a sense of meaning in life arises from religion, then a good deal of religious meaning should be found in the Bible. It follows from this that participation in Bible study groups is an important way of deriving a religious sense of meaning in life, especially if meaning is difficult to discern in some biblical passages.

But something more subtle may also emerge in Mexican American congregations when people strive to find a sense of meaning in church services and Bible study groups. The very process of wrestling with difficult issues and arriving at underlying religious themes involving meaning may take on added significance when it is accomplished within the context of a group. More specifically, participating in church services and Bible study groups in these ways may help individuals develop a sense of identify – a clearer notion of who they are, where they fit in, and the sense of bonding with religious others that arises from these insights. This is important because deriving a clearer sense of identity and stronger feelings of belonging form the basis for finding greater meaning in life (Krause 2008). Perhaps this is one reason why Goizueta (2002) argues that the group plays an especially important role in Mexican American religious practice: “… an inherently communal theological anthropology remains at the heart of the Mexican American understanding of identity as reflected in popular Catholicism” (p. 122).

Religious Meaning and Life Satisfaction

Findings from a number of studies indicate that people who have been able to find meaning in life tend to have a greater sense of life satisfaction (Chamberlain 1988; Stegar and Frazier 2005). Moreover, some of this research has been done with older adults (Krause, 2003). It is especially important to point out that Krause (2003) found that the relationship between a sense of religious meaning and life satisfaction is much stronger for older African Americans than older whites. He explained this finding by arguing that religion takes on added significance for older blacks because it helps them overcome suffering that is associated with centuries of racial discrimination and prejudice.

There is some evidence that religion may perform a similar function for older Mexican Americans. The conquest of Mexico by the Spanish created a great deal of pain and suffering Leon (2004). Carrasco (1990) reports the shocking extent of this problem. He indicates that in 1500 there were 25 million indigenous people living in Mexico, but due to factors such as disease and slavery, this population was reduced to 1 million by 1600. Given these data, it is not surprising to find that Leon (2004) refers to the period of colonization as the “Mexican diaspora” (p. 198). The deleterious consequences of colonization were exacerbated by a number of subsequent historical events including the Mexican American War of 1848, the Mexican Revolution of 1910, and the great labor shortages during World War I. Each of these events rekindled earlier conditions of subordination and diaspora that were encountered during the Spanish colonization. And as Rodriguez (1994) argues, the imprint of these historical events may still be found among contemporary Mexican Americans: “What makes the experience of Mexican Americans unique compared to other ethnic populations that migrated to this country is their psychohistorical experience and their subsequent subjugation – all taking place in what the indigenous peoples considered to be their own land” (Rodriguez 1994, p. 69). Even so, Fernandez (2007) shows how religion has helped Mexican Americans find meaning in the face of these historical difficulties. Citing the work of Espin, Fernandez (2007) argues that, “The Christ of Hispanic passion symbolism is a tortured, suffering human being. The image leaves no room for doubt … He is not just another human who suffers unfairly at the hands of evil humans. He is the divine Christ, and that makes his innocent suffering all the more dramatic …” (p. 102). Fernandez (2007) goes on to point out that “… a vanquished people (can) relate to a suffering Christ” (p. 102). But this type of meaning and solace is likely to be found only among older Mexican Americans who become involved in the church. Those who are unwilling or unable to avail themselves of this potentially important resource may be unable to find a sense of meaning and, as a result, they will be more dissatisfied with the way their lives have turned out.

Exploring Issues Involving Age

Although it is important for adults of all ages to find a sense of meaning in life, there is some evidence that finding meaning becomes increasingly important as people grow older. Turning to the work of Erikson (1959), Tornstam (2005), and Carstensen (Carstensen, Fung, and Charles 2003) helps show why this may be so.

Erikson (1959) provides one reason why it may be especially important for people to derive a sense of meaning when they reach late life. He divided the life span into eight stages. He proposed that a unique developmental challenge or crisis must be resolved in order for people to move from one stage of development to the next. The final stage, which is typically reached at the end of life, is characterized by the crisis of integrity versus despair. This is a time of deep introspection when people review their lives and try to reconcile the inevitable gap between what they set out to do and what they were actually able to accomplish. Viewed more broadly, this means that as people grow older, they try to weave the stories of their lives into a more coherent whole. Ultimately, the goal of this process is to imbue life with a deeper sense of meaning and significance. If older people successfully meet the challenge in this final stage of development, then it is not difficult to see why they are likely to become more satisfied with their lives.

Tornstam (2005) also provides evidence for the increasing importance of meaning with advancing age. His theory of gerotranscendence specifies that as people grow older they experience a major shift in the way they view the world. This shift is characterized by a move away from a materialistic and pragmatic view of the world to more transcendent and cosmic concerns. This cosmic dimension involves an exploration of one’s own inner space and, consistent with the work of Erikson (1959), a search for greater integrity. The process of gerotranscendence also involves a desire for maintaining fewer, but more meaningful social relationships as well as a greater preference for, and appreciation of solitude. Although Tornstam (2005) did not cast his theory explicitly in terms of meaning in life, issues involving the search for meaning clearly lie behind his discussion of introspection, integrity, and the desire for deeper personal relationships. It is especially important to note that Tornstam (2005) found that older people who successfully negotiated the transitions he describes experience greater life satisfaction.

Like Tornstam (2005), Carstensen and her colleagues propose that as people grow older, they experience a shift away from obtaining more pragmatic knowledge and the development of new skills to seeking close emotional relationships with a smaller circle of family members and friends (Carstensen et al. 2003). This shift in priorities is driven by a growing awareness of the shortness of life and a greater desire to derive a sense of meaning. These investigators hint at the relationship between a sense of meaning and life satisfaction when they argue that, “What characterizes old age is not hedonism, but a desire to derive a meaning and satisfaction through life” (Carstensen et al. 2003, p. 108).

Consistent with the theoretical perspectives that were devised by Erikson (1959), Tornstam (2005), and Carstensen et al. (2003), findings from several studies suggest that people who are currently older tend to have a greater sense of meaning in life than individuals who are presently younger. For example, Van Ranst and Marcoen (1997) report that younger adults tend to experience less meaning in life than older people. Similarly, Reker and Fry (2003) found a greater tendency for older adults to experience meaning in life than younger people.

So, if finding a sense of meaning becomes especially important in late life, the inability to do so may have an especially deleterious effect on older people. This is why it is especially important to study the relationship between a religious sense of meaning and life satisfaction in samples that comprise older adults.

Methods

Sample

The population for this study was defined as all Mexican Americans age 66 and over who were retired (i.e., not working for pay), not institutionalized, and who speak either English or Spanish. The sampling frame consisted of all eligible study participants who resided in the following five-state area: Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. The sampling strategy that was used for the widely-cited Hispanic Established Population for Epidemiological Study (HEPESE) (Markides 2003) was adopted for the current study. This sampling strategy was executed in a seven steps. First, using data provided by the Census Bureau, a complete list of counties in the five states were identified and ranked according to the number of Mexican Americans age 66 and older who resided in them. Second, counties where ninety percent of older Mexican Americans reside were retained. Third, a list of census tracts within each county was developed and the number of older Mexican Americans within each census tract was determined. Once again, census tracts where ninety percent of older Mexican Americans resided were retained. Fourth, 125 census tracts were sampled with probabilities proportional to the number of Mexican American elderly. Fifth, a list was created of all the blocks in each census tract. Sixth, a block was selected within each tract with a simple random sampling procedure. Seventh, maps were created for each selected block and the number of housing units on each block was determined. Interviewers then screened the households on each block for eligible study participants. Based on Census estimates, this sampling strategy should cover 82% of all older Mexican Americans in the nation.

All interviews were conducted by Harris Interactive (New York). The interviews were administered face-to-face in the homes of the older study participants. All interviewers were bilingual and study participants had the option of being interviewed in either English or Spanish. The majority of interviews (84%) were conducted entirely in Spanish. A total of 1,005 interviews were completed successfully. The response rate was 52%.

The full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) procedure was used to deal with item non-response. The FIML procedure was selected for this purpose because research reveals that FIML provides data that are equivalent to more time consuming imputation procedures, such as multiple imputation (Schafer and Graham 2002).

Preliminary analyses reveal that the average age of the older Mexican Americans in this sample was 73.9 years (SD = 6.6 years), approximately 44% were older men, the average number of years of schooling was 6.6 (SD = 3.8 years), and approximately 58% were born in Mexico.

Measures

The core measures in this study are provided in Table 1. The procedures used to code the measures are provided in the footnotes of this table. Information on the reliability of constructs that are measured with multiple items is provided later in this report.

Table 1.

Core Study Measures

This item was scored in the following manner (coding in parentheses): U.S. (0); Mexico (1).

This item assesses the total number of years of completed schooling.

These items were scored in the following manner: always (1); frequently (2); sometimes (3); never (4).

This item was scored in the following manner: entirely in Spanish (1); both English and Spanish – more Spanish than English (2); both English and Spanish – more English than Spanish (3); entirely in English (4).

This item was scored in the following manner: none (1); only a little (2); some (3); a great deal (4).

This item was scored in the following manner: money left over (1); just enough (2); not enough money to make ends meet (3).

This item was scored in the following manner: better (1); about the same (2); worse (3).

These items were scored in the following manner: never (1); less than once a year (2); about once or twice a year (3); several times a year (4); about once a month (5); 2 or 3 times a month (6); nearly every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9).

These items were scored in the following manner: strongly disagree (1); disagree (2); agree (3); strongly agree (4).

Country of birth

As shown in Table 1, a single item was administered in order to see whether older Mexican Americans were born in Mexico or the United States. Responses to this question were coded in a binary format where a score of 1 represents being born in Mexico and a score of 0 denotes study participants who were born in the United States. Preliminary analysis suggest that 57.7 % of the older participants in this study were born in Mexico.

Education

The measure of education reflects the total number of years of schooling that older Mexican Americans received credit for completing. A high score denotes more years of schooling.

English language use

Three items were included in the survey to determine how often older study participants speak English. The first indicator assesses how often they speak Spanish with family members and close friends, the second determines how often they watch television programs in Spanish, and the third reflects the extent to which the interview was conducted in Spanish or English. A high score on these indicators denotes greater use of English. The mean of the three items taken together is 4.5 (SD = 1.8).

Financial strain

Three items were used to determine the level of financial strain that older study participants were experiencing. The first indicator reflects how much difficulty they have paying monthly bills, the second assesses whether they have just enough money at the end of the month to make ends meet, and the third indicates whether their financial situation is worse than that of other people their own age. The first two items were taken from the work of Pearlin and his colleagues (Pearlin et al. 1981) whereas the third indicator comes from research by Liang and Fairchild (1979). A high score stands for greater financial strain. When the three items are summed, the mean is 6.2 (SD = 2.1).

Organizational religious involvement

Consistent with the theoretical rationale that was devised for this study, formal involvement in the church was measured with two indicators. The first assesses how often older study participants attended worship services in the past year. The second item was designed to determine how often older Mexican American study participants attend Bible study groups. A high score stands for more frequent involvement in the church. When these two items are summed, the mean is 7.4 (SD = 4.4).

Religious meaning in life

A sense of religious meaning in life was assessed with three items that were developed by Krause (2003). These indicators were designed to determine whether God has a purpose for the lives of study participants, whether He has a plan for their lives, and whether God has a reason for everything that happens to them. A high score stands for a greater sense of religious meaning in life. The mean of this brief composite is 10.5 (SD = 1.5).

Life satisfaction

A brief three-item measure was used to assess life satisfaction. The first two indicators are from the Life Satisfaction Index A (Neugarten, Havighurst, and Tobin 1961). The third item, which is used frequently in research, assesses satisfaction with life as a whole. A high score on these indicators means that study participants feel more satisfied with the way their lives have turned out. The average score on this short battery of items is 10.0 (SD = 1.8).

Demographic control variables

As discussed earlier, the relationships among the variables in Figure 1 were estimated after the effects of age and sex were controlled statistically. Age is scored continuously in years and sex is coded in a binary variable (1 = men; 0 = women).

Results

Fit of the Model to the Data

The model depicted in Figure 1 was estimated with Version 8.80 of the LISREL statistical software program (du Toit and du Toit 2001). The maximum likelihood option was used for this purpose. However, researchers who use this estimator must assume that the observed indicators in a study model have a multivariate normal distribution. Preliminary tests (not shown here) revealed that this assumption had been violated. Following the recommendations of du Toit and du Toit (2001), departures from multivariate normality were handled by converting raw scores on the observed indicators to normal scores prior to estimating the model (see p. 143).

Because the FIML procedure was used to deal with item non-response, the LISREL software program only provides two goodness-of-fit measures. The fist is the full information maximum likelihood chi-square value (278.398 with 103 degrees of freedom, p < .001). Unfortunately, this statistic is not informative because the sample for this study is large. However, the second goodness-of-fit measure is more useful – the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The RMSEA value for the study mode is .041. As Kelloway (1998) reports, values below .05 indicate a very good fit of the model to the data.

Reliability of Multiple Item Study Measures

Table 2 contains the factor loadings and measurement error terms that were derived from estimating the study model. These coefficients are important because they provide preliminary information about the reliability of the multiple item indicators. Kline (2005) recommends that items with standardized factor loadings in excess of .600 tend to have good reliability. As the data in Table 2 indicate, the standardized factor loadings range from .555 to .922. Only two coefficients were below .600, and the difference between these estimates and the recommended value of .600 is trivial.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings and Measurement Error Terms for Multiple Item Measures (N = 1,005)

| Construct | Factor Loadinga | Measurement Errorb |

|---|---|---|

| 1. English Language Use | ||

| A. TV in Spanishc | .772 | .404 |

| B. Spanish with family | .768 | .411 |

| C. Language of interview | .700 | .509 |

| 2. Financial Strain | ||

| A. Difficulty with monthly bills | .823 | .322 |

| B. Finances work out | .761 | .421 |

| C. Finances compared to others | .629 | .604 |

| 3. Organizational Religious Involvement | ||

| A. Religious services | .555 | .692 |

| B. Attend Bible study groups | .709 | .497 |

| 4. Religious Meaning in Life | ||

| A. God has a purpose | .992 | .151 |

| B. God has a plan | .884 | .218 |

| C. God has a reason | .695 | .517 |

| 5. Life Satisfaction | ||

| A. Best years of my life | .582 | .661 |

| B. Look back on life | .745 | .445 |

| C. Would not change the past | .785 | .384 |

The factor loadings are from the completely standardized solution. The first-listed item for each latent construct was fixed to 1.0 in the unstandardized solution.

Measurement error terms are from the completely standardized solution. All factor loadings and measurement error terms are significant at the .001 level.

Item content is paraphrased for the purpose of identification. See Table 1 for the complete text of each indicator.

Although obtaining information about the reliability of each item is useful, it would also be helpful to know something about the reliability for the multiple item scales as a whole. Fortunately, it is possible to compute these estimates with a formula provided by DeShon (1998). This procedure is based on the factor loadings and measurement error terms in Table 2. Applying the procedures described by DeShon (1998) to these data yields the following reliability estimates for the multiple item constructs in Figure 1: English language use (.791), financial strain (.784), religious meaning in life (.876), and life satisfaction (.750). No attempt was made to compute a reliability estimate for the measure of formal involvement in the church because it consists of only two items. However, preliminary analysis (not shown in Table 2) reveals that the two items are significantly correlated (r = .394; p < .001).

Substantive Findings

Data on the relationships among the variables in the study model are provided in Table 3. Taken as a whole, the findings in this table provide support for the core study hypotheses.

Table 3.

Financial Strain, Religious Involvement and Life Satisfaction (N = 1,005)

| Independent Variables | Education | Use of English | Dependent Variables | Religious Meaning | Life Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Strain | Church Involvement | |||||

| Age | −.131***a (−.079)b |

−.074* (−.008) |

−.100** (−.013) |

−.157*** (−.032) |

.030 (.002) |

.084* (.006) |

| Sex | −.022 (−.174) |

.059* (.086) |

−.043 (−.075) |

−.200*** (−.532) |

−.099** (−.101) |

.044 (.043) |

| Country of birth | −.429*** (−3.450) |

−.449*** (−.653) |

.016 (.029) |

.149** (.399) |

−.059 (−.060) |

−.182*** (−.182) |

| Education | .355*** (.064) |

−.179*** (−.039) |

−.097 (−.032) |

.041 (.005) |

.010 (.001) |

|

| Use of English | −.255*** (−.273) |

.197** (.363) |

−.110* (−.077) |

−.178** (−.122) |

||

| Financial strain | −.231*** (−.349) |

−.055 (−.032) |

−.366*** (−.207) |

|||

| Church involvement | .257*** (.098) |

.153** (.057) |

||||

| Religious meaning | .275*** (.270) |

|||||

| Multiple R2 | .190 | .458 | .140 | .137 | .092 | .320 |

Standardized coefficient

Metric (unstandardized) coefficient

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

The results in Table 3 reveal that older study participants who were born in Mexico tend to have less education than older adults who were born in the United States (Beta = −.429; p < .001). The findings indicate that older Mexican Americans with lower levels of educational attainment are, in turn, less likely to speak English often (Beta = .355; p < .001). This is important because as the data in Table 3 further suggest, older Mexican Americans with lower levels of educational attainment (Beta = −.179; p < .001) who use English less often (Beta = −.225; p < .001) are more likely to experience financial strain. Consistent with the theoretical framework that was developed for this study, the results in Table 3 indicate that older Mexican Americans who experience more financial strain are less likely to participate in formal church activities than older Mexican Americans who have encountered fewer economic problems (Beta = −.231; p < .001). This is important because the data further suggest that older Mexican Americans with less formal religious involvement tend to have a diminished sense of religious meaning in life (Beta = .257; p < .001). And as several other investigators report, a diminished sense of religious meaning in life is associated with lower levels of life satisfaction (Beta = .275; p < .001).

One of the advantages of working with latent variable models arises from the fact that it is possible to assess the indirect and total effects of a variable that operate through a model. A simple example helps clarify the meaning of these terms. The model in Figure 1 specifies that financial strain is associated with diminished participation in the church, and less involvement in formal church activities is, in turn, associated with a diminished sense of religious meaning in life. Stated in a more technical way, this means that financial strain affects religious meaning indirectly through the less formal involvement in the church. When the direct effect of financial strain on religious meaning is added to the indirect effect that operates through organizational religious involvement, the resulting total effect provides a broader vantage point for assessing the role that financial strain plays in limiting an older Mexican American’s opportunity to develop a religious sense of meaning in life. Breaking down the effect of a construct into direct, indirect, and total effects is known in the literature as the decomposition of effects (Alwin 1988).

A decomposition of effects was performed for four core sets of relationships in the study model. The first follows through on the example provided above. More specifically, empirical estimates were derived for the direct, indirect, and total effects of financial strain on a religious sense of meaning in life. The data in Table 3 suggest that financial strain does not appear to affect whether older Mexican Americans develop a religious sense of meaning in life (Beta = −.055; n.s.). But this coefficient only represents the direct effects of financial strain on meaning. Consistent with the rationale provided above, further analysis (not shown in Table 3) suggests that the indirect effect of financial strain on meaning that operates through formal involvement in the church is statistically significant (Beta = −.059; p < .001). When the direct and indirect effects are summed, the resulting total effect (not shown in Table 3) reveals that greater financial strain is associated with a diminished sense of religious meaning in life (−.055 + −.059 = −.115; p < .01). Put another way, these data suggest that approximately 51% of the total effect of financial strain on meaning operates indirectly through formal involvement in the church (−.059/−.115 = .513).

Further insight into the underlying processes that operate through the study model may be found by decomposing the effect of formal involvement in the church on life satisfaction. The data in Table 3 suggest that greater involvement in formal activities at church is associated with greater life satisfaction (Beta = .153; p < .001). However, the conceptual model that was developed for this study further specifies that greater involvement in church is associated with a deeper sense of religious meaning, and the ability to find more meaning is, in turn, associated with greater life satisfaction. So, when the indirect effect of formal religious involvement on life satisfaction (Beta = .071; p < .001) is added to the direct effect, the resulting total effect (Beta = .224; p < .001) is significantly larger. As these findings reveal, a sense of life satisfaction among older Mexican Americans is shaped, in part, by the extent to which they participate in formal church activities, and 32% of this effect is explained by the deeper sense of religious meaning that arises from greater involvement in the church (.071/.224 = .316).

Third, as discussed earlier, approximately 58% of the older participants in this study immigrated from Mexico. A decomposition of effects was performed to determine the role that this may play in increasing risk to financial strain. The findings in Table 3 initially create the impression that immigrating from Mexico is not significantly associated with greater financial strain (Beta = .016; n.s.). However, the model in Figure 1 specifies that nativity status is associated with education, education determines English language use, and less frequent use of English is associated with greater financial strain. Stated more formally, immigration status may affect financial strain indirectly through education and English language use (Beta = .212; p < .001). When the indirect effect is added to the direct effect, the resulting total effect is fairly substantial (Beta = .228; p < .001). Simply put, the mediating effects of education and English language use almost completely explain why immigrants from Mexico encounter more economic difficulty in the United States.

The final decomposition has to do with the relationship between financial strain and life satisfaction. Research indicates that greater financial strain is associated with diminished feelings of life satisfaction among older adults (Krause 1993). However, it is not entirely clear how the deleterious effects of financial strain arise. The model in Figure 1 suggests that greater involvement in religion may have something to do with it. The data in Table 3 suggest that greater financial strain is associated with a diminished sense of life satisfaction (Beta = −.366; p < .001). However, the findings also indicate that the indirect effect of financial strain on life satisfaction that operates through formal involvement in the church and religious meaning is also statistically significant (Beta = −.067; p < .001). Summing the direct and indirect effects reveals that the total effect of financial strain on life satisfaction is significantly larger (Beta = −.433; p < .001). Moreover, about 15% of the total effect is explained by less involvement in the church and diminished religious meaning (−.067/−.433 = .155).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among financial strain, involvement in religion, and life satisfaction among older Mexican Americans. Greater insight into the relationships among these constructs was derived by developing a conceptual model that had three principle aims. The first was to briefly assess the factors that play a role in the genesis of financial difficulty. Consistent with previous research, the findings that were obtained by estimating this model suggest that older study participants who were born in Mexico have fewer years of school and they are less likely to speak English than older study participants who were born in the United States. This is important because, as the data further reveal, older Mexican Americans with lower levels of educational attainment and less frequent use of English are more likely to encounter economic difficulty in late life.

The second aim of the study model was to see if greater financial strain is associated with involvement in religion. An effort was made to assess religious involvement in two ways that have not been evaluated previously in the literature. The findings suggest that older Mexican Americans who experience economic problems are less likely to attend religious services and Bible study groups than older Mexican Americans who are more financially secure. This turned out to be important because the data further indicate that older Mexican Americans who are less involved in the church are less likely to find a sense of religious meaning in life.

The third aim of the study model was to see if diminished involvement in religion is associated, in turn, with lower levels of life satisfaction. The results reveal that older Mexican Americans who are less involved in formal church activities tend to feel less satisfied with their lives than older Mexican Americans who participate in worship services and Bible study groups. Moreover, the data suggest that older Mexican Americans who do not have a strong sense of religious meaning also tend to be less satisfied with the way their lives turned out.

When viewed at the broadest level, the findings from the current study show how the ability to obtain greater life satisfaction through involvement in religion is determined, to a significant extent, by the overriding influence of social structural factors (e.g., education and financial difficulties). But the way in which this process operates appears to be at odds with the classic Marxist views of religion. Proponents of the Marxist perspective argue that people who have been deprived of wealth and power are more likely to turn to religion for solace (see, for example, Pals 1996). However, the findings from the current study suggest that instead of becoming more deeply involved in religion, more economically challenged individuals turn away from formal religious activities and, as a result, they are less likely to adopt the sense of meaning that religion may provide.

Even though the findings from the current study may contribute to the literature, a substantial amount of research remains to be done. Four issues should be given high priority. First, when the theoretical rationale for this study was presented, it was proposed that older Mexican Americans who encounter more economic difficulty may be less involved in religion because they are more distrustful and they are more angry and hostile. Yet measures of distrust, hostility, and anger were not included in the analyses. It is important to examine the potentially important role these factors may play in shaping the extent of formal religious involvement among older Mexican Americans. Second, only two measures of religion were examined in this study. However, researchers have known that there is far more to religion than involvement in formal church activities and religious meaning (Fetzer/National Institute on Aging Working Group 1999). More research is needed to explore the ways in which other dimensions of religion may influence life satisfaction among older Mexican Americans. For example, studies should be conducted to see whether informal relationships in the church influence life satisfaction. Third, an effort should be made to expand the study model by seeing whether it explains a range of health-related outcomes, including physical health status, mental health, and mortality. Fourth, a good deal has been written about the family in Mexican American culture (Fernandez 2007). Consequently, research is needed on the ways in which family relationships may influence the constructs contained in Figure 1.

In the process of exploring other issues in the relationship between religion and life satisfaction among older Mexican Americans, researchers should pay careful attention to the limitations in this study. One is especially important. The data for this study were gathered at one point in time. Therefore, the causal ordering among the variables in the study model were based on theoretical considerations alone. This makes it possible to reverse some of the causal specifications in the study model. For example, it was proposed that religious meaning determines life satisfaction. But one could just as easily argue that older Mexican Americans who are satisfied with their lives may be more open to exploring the ways in which religion may help them find a sense of meaning. Clearly this, as well as other causal assumptions in the study model, must be evaluated with data that have been gathered at more than one point in time.

Although there are shortcomings in this study, it is hoped that the issues examined will encourage other investigators to turn their attention to a vastly understudied population in the literature on religion and health – older Hispanics. Recent Census projections indicate that by the year 2050, older Hispanics will surpass older African Americans to become the second largest minority group in the nation (Vincent and Velkoff 2010). As these sweeping demographic changes reveal, researchers who hope to stay on the cutting edge of research on religion and health have no choice other than to delve more deeply into the community of older Mexican Americans.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG014749; RO1 AG026259) and a grant from the John Templeton Foundation that was administered through the Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health, at Duke University.

Contributor Information

Neal Krause, University of Michigan.

Elena Bastida, Florida International University.

References

- Alwin Duane F. Structural Equation Models in Research on Human Development and Aging. In: Warner Schaie K, Campbell Richard T, Meredith W, Rawlings Samuel C, editors. Methodological Issues in Aging Research. New York: Springer; 1988. pp. 71–170. [Google Scholar]

- Belle Deborah. Social Ties and Social Support. In: Belle Deborah., editor. Lives in Stress: Women and Depression. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1982. pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Peter L. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory. New York: Doubleday; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco David. Religion of Mesoamerica: Cosmovision and Ceremonial Centers. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen Laura L, Fung Helene H, Charles Susan T. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory and the Regulation of Emotion in the Second Half of Life. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:103–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain Kerry. Religiosity, Life Meaning, and Well-Being: Some Relationships in a Sample of Women. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1988;27:411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WH. The Psychology of Religion. New York: Macmillan; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- DeShon Richard P. A Cautionary Note on Measurement Error in Structural Equation Models. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:412–423. [Google Scholar]

- du Toit Mathilda, du Toit Stephen. Interactive LISREL: User’s Guide. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson Eric. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York: International University Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging Related Statistics. Older Americans, 2010: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Eduardo C. Mexican American Catholics. New York: Paulist Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl Victor E. Man’s Search for Meaning. New York: Washington Square Press; 1959/1985. [Google Scholar]

- Goizueta Roberto S. The Symbolic World of Mexican American Religion. In: Matovina Timothy, Riebe-Estrealla Gary., editors. Horizons of the Sacred: Mexican Traditions in US Catholicism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2002. pp. 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll Stephen E. Stress, Culture, and Community: The Psychology and Philosophy of Stress. New York: Plenum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi Yolande, Hull RFC. C G Jung Psychological Reflections: A New Anthology of His Writings 1905–1961. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin Kelloway E. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kline Rex B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koltko-Rivera Michael E. Rediscovering the Later Version of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Self-Transcendence and Opportunities for Theory, Research, and Unification. Review of General Psychology. 2006;10:302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal. Stress and Isolation from Close Ties in Later Life. Journal of Gerontology. 1991;46:S183–S194. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.4.s183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal. Neighborhood Deterioration and Social Isolation in Late Life. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1993;36:9–38. doi: 10.2190/UBR2-JW3W-LJEL-J1Y5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal. Religious Meaning and Subjective Well-Being in Late Life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2003;58B:S160–S170. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.3.s160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal. Aging in the Church: How Social Relationships Affect Health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal, Goldenhar Linda M. Acculturation and Psychological Distress in Three Groups of Elderly Hispanics. Journal of Gerontology. 1992;47:S279–S288. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.6.s279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause Neal, Newsom Jason T, Rook Karen S. Financial Strain, Negative Interaction, and Self-Rated Health: Evidence from Two United States Nationwide Longitudinal Surveys. Aging & Society. 2008;28:1001–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Leon Luis D. La Llorona’s Children: Religion, Life, and Death in the US-Mexican Borderlands. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Levin Jeffrey S, Markides Kyriakos S. Religion and Health in Mexican Americans. Journal of Religion and Health. 1985;24:60–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01533260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Jersey, Fairchild Thomas. Relative Deprivation and Perception of Financial Adequacy among the Aged. Journal of Gerontology. 1979;34:746–759. doi: 10.1093/geronj/34.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Karen D. Financial Strain, Negative Interactions, and Mastery: Pathways to Mental Health among Older African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33:439–462. doi: 10.1177/0095798407307045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides Kyriakos S. Hispanic Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly 1993–1994. Study Number 2851. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow Abraham H. Toward a Psychology of Being. New York: Van Nostrand; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon Carlos F, Rapp Stephen S, Kasl Stanislav V. Financial Strain and Symptoms of Depression in a Community Sample of Elderly Men and Women: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Aging and Health. 1994;6:448–468. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Education, Social Status, and Health. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten Bernice, Havighurst RJ, Tobin Sheldon S. The Measurement of Life Satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology. 1961;16:134–143. doi: 10.1093/geronj/16.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pals Daniel L. Seven Theories of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament Kenneth I. The Psychology of Religious Coping: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I, Menaghan Elizabeth, Lieberman Morton, Mullan John. The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reker Gary T, Fry Prem S. Factor Structure and Invariance of Personal Meaning Measures in Cohorts of Younger and Older Adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35:977–993. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer Sam. Class and Congregations: Class and Religious Affiliation at the Congregational Level of Analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2007;46:583–594. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Jeanette. Our Lady of Guadalupe: Faith and Empowerment among Mexican-American Women. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Van Willigen M. Gender, Parenthood, and Anger. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:572–584. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer Joseph L, Graham John W. Missing Data: Our View of the State of the Art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz James H. The Economics of Aging. Westport, CT: Auburn House; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Steger Michael F, Frazier Patricia. Meaning in Life: One Link in the Chain from Religiousness to Well-Being. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Tornstam Lars. Gerotranscendence: A Developmental Theory of Positive Aging. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ranst Nancy, Alfons Marcoen. Meaning in Life of Young and Older Adults: An Examination of the Factorial Validity and Invariance of the Life Regard Index. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;22:877–884. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent Grayson K, Velkoff Victoria A. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, DC: U. S. Census Bureau; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wink Walter. Wrestling with God: Psychological Insights in Bible Study. In: Rollins Wayne G., editor. Psychology and the Bible: A New Way to Read the Scriptures. Westport, CT: Praeger Publications; 2004. pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]