Abstract

Effective vaccines against intracellular pathogens rely on the generation and maintenance of memory CD8 T cells (Tmem). Hitherto, evidence has indicated that CD8 Tmem use the common gamma chain cytokine IL-15 for their steady-state maintenance in the absence of antigen. This evidence, however, has been amassed predominantly from models of acute, systemic infections. Given that the route of infection can have significant impact on the quantity and quality of the resultant Tmem, reliance on limited models of infection may restrict our understanding of long-term CD8 Tmem survival. Here we show IL-15-independent generation, maintenance, and function of CD8 Tmem following respiratory infection with influenza virus. Importantly, we demonstrate that alternating between mucosal and systemic deliveries of the identical virus prompts this change in IL-15 dependence, necessitating a reevaluation of the current model of CD8 Tmem maintenance.

Introduction

An effective host defense following reinfection with an intracellular pathogen relies on the generation and maintenance of memory CD8 T cells (Tmem). Therefore, there has been considerable investigation into the signals that govern these processes, as their exploitation could aid in vaccine development. The current model of Tmem development dictates that following pathogen clearance a small proportion of effector CD8 T cells (Teff) survive and emerge as a stable Tmem pool that is maintained in the absence of Ag via sustained cytokine signaling (1). IL-7 and IL-15 are members of the common gamma chain (γc) family of cytokines that retain the steady-state numbers of Tmem, although their contributions to the maintenance of CD8 Tmem are not necessarily redundant (2).

While there is considerable evidence substantiating the role of γc cytokines in CD8 Tmem development and maintenance, there remain contexts in which to explore these roles. The landmark studies implicating IL-15 in the maintenance of CD8 Tmem were conducted in models of acute, systemic infection where intravenous infection of IL-15−/− mice with vesicular stomatitis (VSV) or lymphocytic choriomeningitis viruses (LCMV) resulted in the reduction of Ag-specific CD8 Tmem, with Tmem attrition exacerbated over time (3-5). Alterations in type or route of infection, however, can impact the CD8 Tmem pool. Qualitatively different CD8 Tmem is generated in response to Ag delivered by either the mucosal or systemic route (6), and these different Tmem populations may require distinct homeostatic signals for their proliferation and survival.

The majority of pathogens causing human diseases enter the host via a mucosal route, and unlike their systemically derived counterparts, the longevity of mucosal CD8 Tmem is limited (7). Importantly, following influenza infection, protection from challenge with heterosubtypic viruses is highly correlated with the retention of a pool of Tmem in the airways (8-9). We hypothesized that limited availability of IL-15 or the loss of IL-15 responsiveness by airway-resident Tmem was responsible for this attrition. We demonstrate, however, that loss of IL-15 neither prevents the generation of Tmem nor accelerates the loss of mucosally-generated, influenza-specific CD8 Tmem in the airways or the periphery. Moreover, altering the route of infection correspondingly alters the requirement for IL-15 in CD8 T cell homeostasis. Together our data demonstrate that both IL-15-dependent and independent Tmem pools exist, and CD8 T cells primed in the mucosa require distinct signals for their long-term maintenance.

Materials and Methods

Mice, viruses, and infection

Age and sex-matched C57Bl/6 and IL-15−/− mice were purchased from NCI (Bethesda, MD) and Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). Drs. S. Mark Tompkins (University of Georgia, Athens, GA) and Leo Lefrançois (University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT) generously provided the influenza viruses (A/HK-x31[x31, H3N2] and A/PR/8 [PR8, H1N1]) and VSV-NJ, respectively. Animals were infected intranasally (i.n.) with 103 pfu x31, 5×103 pfu of PR8 or 104 pfu of VSV or intravenously (i.v.) with 104 pfu VSV.

Tissue preparation and flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were obtained from spleens, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood and depleted of erythrocytes using Tris-buffered NH4Cl. Airway-resident and lung parenchyma lymphocytes were isolated as previously described (11).

MHC class I tetramers reactive against the influenza nucleoprotein (NP) (H-2D(b)/ASNENMETM) and VSV NP (H-2K(b)/RGYVYQGL) were generated by the NIAID Tetramer Facility (Emory University). Tetramer staining was conducted at RT 1 hr with other indicated mAbs (eBiosciences (San Diego, CA), BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA), or BioLegend (San Diego, CA)). For 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) staining, 0.8 mg/mL BrdU (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was added to drinking water. Isolated cells were intracellulary stained with FITC-labeled αBrdU (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) and analyzed on a BD LSR II digital flow cytometer with BD FACs Diva software.

Plaque and in vivo CTL assays

For plaque assays, lungs from x31-immune WT and IL-15−/− mice challenged with PR8 7d previously were processed and incubated with a monolayer of MDCK cells as previously described (11). Monolayers were washed, overlaid with MEM containing 1.2% Avicel microcystalline cellulose (FMC BioPolymer, Philadelphia, PA), 0.04M HEPES, 0.02 mM L-glutamine, 0.15% NaHCO3, and 1μg/ml TPCK-trypsin, and 72 hrs post infection (p.i.), monolayers were fixed and stained with crystal violet.

For in vivo CTL assays, half the splenic targets were pulsed with 10 μM influenza NP peptide (ProImmune, Bradenton, FL) for 1 hr at 37°C and the remainder unpulsed, labeled with 10 μM and 1 μM CFSE respectively, and 2×106 targets were injected 50:50 into recipient mice. 15 hrs later, percent target killing was calculated as 100−((% of NP-pulsed targets in infected recipients / % unpulsed targets in infected recipients) / (% NP-pulsed targets in naïve recipients / % unpulsed targets in naïve recipients) × 100).

Statistics

Unpaired two-tailed student’s T test was applied using Prism software (Graphpad, Dan Diego, CA). P values are indicated in the figure legend where statistical significance was found.

Results and Discussion

IL-15 is dispensable for the generation and maintenance of influenza-specific CD8 Tmem

Following infection with influenza virus, a population of Ag-specific CD8 T cells are activated, migrate to the lung airways, and differentiate into CD8 Tmem where, if maintained in adequate number, confer protection to heterologous infections (7-9). Unfortunately, in the months following infection, this population declines, despite the fact that a reservoir of splenic CD8 Tmem continues to migrate to the lung airways to maintain steady-state numbers (10). Since CD8 Tmem in other models of acute viral infection require IL-15 for their long-term survival (3-5), we hypothesized that the limited longevity of the protective CD8 Tmem in the lung airways following influenza infection is due to limited availability of IL-15 at this site.

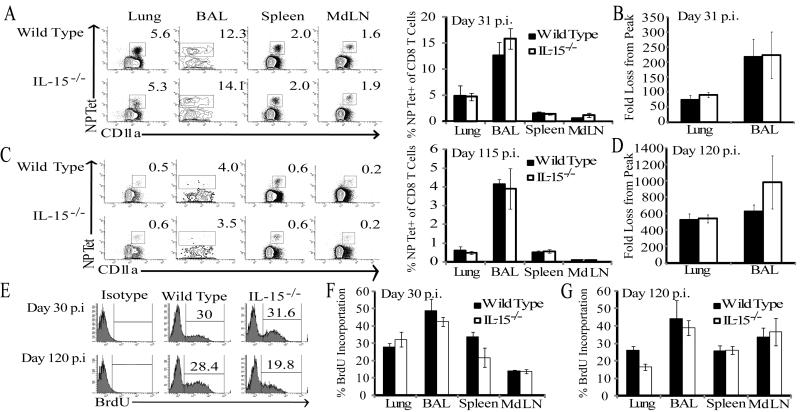

To first determine whether IL-15 is required for the generation of influenza-specific CD8 Tmem, we infected C57Bl/6 wild type (WT) and IL-15−/− mice with x31 influenza and monitored the CD8 T cell response to influenza NP via MHC class I tetramers in the blood over time. The frequency of NP-specific CD8 T cells in the circulation of IL-15−/− mice remained similar to WT animals 40 days p.i. (data not shown). Thus, in contrast to studies with VSV (3), we found no defect in influenza-specific CD8 Tmem in the absence of IL-15. Other studies, however, have found IL-15 to be essential only for the maintenance of CD8 Tmem (4-5). Therefore, it was possible that following full differentiation and trafficking to specific sites, influenza-specific Tmem would gradually become more dependent on IL-15 for survival. To test this, we collected lymphocytes from the BAL, lung parenchyma, spleen, and lung-draining mediastinal lymph nodes (MdLN) of WT and IL-15−/− mice at an early memory time point (day 31) and later (day 115) p.i.. While the overall frequency of NP-specific Tmem decreased between days 31 and 115 p.i. in WT and IL-15−/− animals, both groups harbored a similar frequency of NP-specific CD8 T cells in all tissues (Fig 1 A, C). Because the majority of CD8 T cells in the lung and lung airways are influenza-specific following infection, it is possible that IL-15 could have an important homeostatic effect on CD8 Tmem in these sites without any obvious changes in the overall frequencies of these cells in IL-15−/− mice. However, comparisons of the numerical fold loss of influenza-specific CD8 Tmem days 30 and 120 p.i. also did not reveal any differences in the attrition of memory cells between WT and IL-15−/− mice over time (Fig 1B, D). Surprisingly, not only did the IL-15 deficiency fail to exacerbate the loss of CD8 Tmem from the airways, the frequency of splenic CD8 Tmem recovered was unaltered, even though 40-60% of these cells express CD122, which is required to receive survival signals from transpresented IL-15 (13) (data not shown). Additionally, frequencies of CD8 Tmem specific for other influenza epitopes were similar in all tissues at day 35 p.i. (Supplemental Fig 1). Thus, while IL-15 contributes to the migration of antigen-specific CD8 T cells at the effector stage of the immune response to influenza (11), it does not contribute to development and homeostatic maintenance of these CD8 T cells once differentiated into memory at either the site of infection or in the periphery.

Figure 1. IL-15 is not required for the homeostatic maintenance of influenza-specific CD8 Tmem.

At day 31 (A) and 115 (C) post x31 infection, CD8+ T cells were isolated from the specified tissues and analyzed for tetramer reactivity and CD11a expression. Representative flow plots for the individual tissues from WT and IL-15−/− mice are shown. The mean percent NP-Tet+ of total CD8+ T cells are plotted for WT (shaded bars) and IL-15−/− (open bars) ± SEM on d 31 p.i. (n=3-4 mice/group; data represent 3 independent experiments) and on d 115 p.i. (n=5 mice/group). At days 10, 31 (B) and 120 (D) p.i., NP-Tet+ CD8 T cells were quantified in the lung and lung airways. Fold loss from peak was calculated as (# NP-Tet+ CD8 T cells at d 31 or 120) / (Avg # NP-Tet+ CD8 T cells at d10). (E) Representative flow plots for intracellular anti-BrdU staining in NP-Tet+ CD8 T cells from lungs of WT and IL-15−/− mice 15d after BrdU infusion in drinking water. The mean percent BrdU+ among NP-Tet+ CD8+ T cells are plotted for WT (shaded) and IL-15−/− (open) mice ± SEM on days 30 (F) and 120 p.i. (G) (n=3 mice/group).

The homeostatic proliferation of influenza NP-specific CD8 Tmem in WT and IL-15−/− mice is equivalent

IL-15 is important for the homeostatic proliferation of CD8 Tmem, whereas other γc cytokines such as IL-7 are more important for providing pro-survival signals to CD8 Tmem (14). To determine whether IL-15 is required for the homeostatic proliferation of Tmem derived from a mucosal infection, we examined the incorporation of BrdU by NP-tetramer+ CD8 Tmem cells isolated from WT and IL-15−/− mice. On both days 30 and 120 p.i. the percentage of replicating NP-specific CD8 Tmem was similar in all tissues of WT and IL-15−/− mice (Fig 1E-G). Thus, in contrast to models of systemic viral infection where CD8 Tmem turn-over was severely impaired over time, CD8 Tmem homeostasis following respiratory infection persists independently of IL-15 signaling.

The differentiation of influenza-specific CD8 Tmem subsets is unaltered in IL-15−/− mice

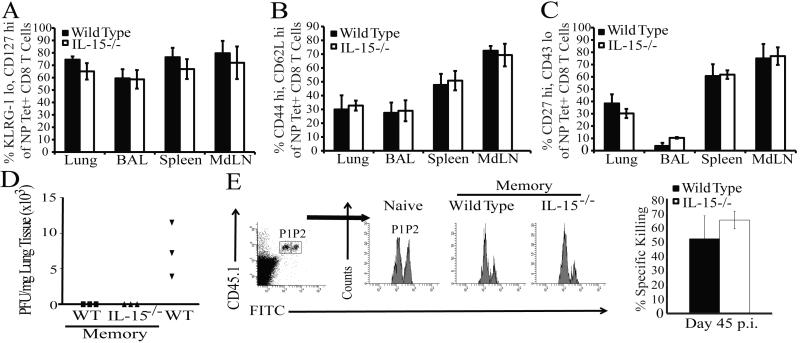

In the linear model of Tmem development, transitioning CD8 Teff can elect one of two fates delineated by the distinct expression of the killer-lectin-like receptor G-1 (KLRG-1) and the IL-7 Rα chain (CD127), which denote KLRG-1hiCD127lo short-lived effector cells (SLECs) and KLRG-1loCD127hi memory precursor effector cells (MPECs) (15). IL-15 has been shown to be particularly important for the survival of SLECs during the contraction phase of the CD8 T cell response (16). Consistent with these findings, frequencies of NP-specific MPECs were slightly elevated in the tissues of IL-15−/− animals at day 32 p.i. (data not shown). However, by d115 post influenza infection, frequencies of MPECs were equivalent in IL-15−/− and WT mice (Fig 2 A), indicating that even though SLECs were rapidly lost in the absence of IL-15 signaling, MPECs were preserved as they transition into a memory population.

Figure 2. Neither the maintenance nor the function of specific influenza NP-reactive CD8 Tmem subsets is altered in IL-15−/− mice.

NP-Tet+ CD8 T cells from the indicated tissues were analyzed for CD127 and KLRG-1 (A), CD44 and CD62L (B), and CD27 and CD43 (C) expression on day 115 post x31 infection (gating strategy in Supplemental Fig. 2). Mean frequencies among total NP-Tet+ CD8+ T cells are plotted ± SEM for WT (shaded) and IL-15−/− (open) mice (n=4-6 mice/group). (D) Viral titers from the lungs of WT (squares) and IL-15−/− (triangles) memory or WT naïve (inverted triangles) mice as determined by plaque assay (n=3 mice/group). (E) Representative flow plots for in vivo killing of unpulsed (P1) and influenza NP-pulsed (P2) target cells in naïve WT or WT and IL-15−/− memory mice 45 days p.i.. CFSE+ populations were gated as indicated. The mean percent specific killing (P2, right) is depicted for WT (shaded) and IL-15−/− (open) ± SEM (n=3 mice/group). Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Moreover, CD8 Tmem are phenotypically heterogeneous and may be sub-classified as either CD62Llo extra lymphoid tissue-homing effector memory (Tem) or CD62Lhi lymphoid-homing central memory (Tcm) (17). To test whether an IL-15 deficiency differentially affected a specific Tmem subset, we monitored the expression of CD62L on influenza-specific CD8 T cells in both WT and IL-15−/− mice over time. The kinetics of CD62L expression on the NP-specific CD8 T cells in the blood (data not shown) and tissues of both IL-15−/− and WT animals was similar at d115 p.i. (Fig. 2 B), demonstrating that the sustained ratio of influenza-specific Tcm and Tem generated in the presence or absence of IL-15 is equivalent. Recently, work in respiratory models of infection demonstrated that CD27hiCD43lo CD8 Tmem mediate superior recall responses in the lung (18). Therefore, we assayed the frequency of CD27hiCD43lo CD8 Tmem in WT and IL-15−/− mice at day 115 p.i. and determined that this phenotype of CD8 Tmem was similar in both groups of animals (Fig 2C). Thus, although the possibility exists that an IL-15-independent subset of CD8 Tmem expands to compensate for the loss of an IL-15-dependent CD8 Tmem subset, using three different Tmem subset phenotypes we could observe no requirement for IL-15 in maintaining distinct CD8 Tmem populations following influenza infection.

CD8 Tmem generated in IL-15−/− mice is fully functional

True immunological memory is defined by the ability of Ag-specific CD8 Tmem to rapidly control an infection after a secondary encounter. Although similar frequencies of influenza-specific CD8 Tmem were maintained in WT and IL-15−/− mice, an IL-15 deficiency could functionally impair the memory population as observed in other studies (19). To test this possibility, x31-immune WT and IL-15−/− or naïve WT mice were challenged with a lethal dose of PR8, the heterosubtypic H1N1 influenza virus that shares a conserved NP protein with x31. Day 7 post challenge virus in the lung was quantified by plaque assay. While naïve animals averaged 750 pfu/mg lung tissue, the lungs of both WT and IL-15−/− memory mice were completely devoid of virus (Fig. 2 D). The functionality of NP-specific CD8 Tmem generated in the absence of IL-15 was also tested via an in vivo CTL assay. Equal numbers of naïve splenocytes pulsed either with or without influenza NP-peptide and differentially labeled with CFSE were injected into WT and IL-15−/− mice 45 days post infection with x31. Fifteen hrs post transfer, spleens of recipient animals were harvested and the percentage of specific killing was determined. Both WT and IL-15−/− influenza-immune recipient mice killed ~55% of the peptide pulsed targets (Fig. 2 E). Together, these data indicate that the functional quality of the CD8 Tmem is preserved independent of IL-15.

Route of infection alters the requirements for IL-15 by CD8 Tmem

While the frequency of VSV and LCMV-specific CD8 Tmem decayed over time in IL-15−/− mice (3-5), we failed to observe any accelerated loss of influenza-specific CD8 Tmem in any site. A major difference between these studies is the route of infection which can alter CD8 T cell responses (6). Thus, to directly test the hypothesis that the route of infection results in a differential requirement of Ag-specific CD8 Tmem cells for IL-15, WT and IL-15−/− mice were systemically (i.v.) or mucosally (i.n.) infected with VSV. On day 30 p.i., lymphocytes were examined for reactivity with the VSV NP-tetramer. As observed previously (4), the frequency of NP-specific CD8 Tmem cells in IL-15−/− mice was reduced by ~50% after systemic infection (Fig. 3). In contrast, however, WT and IL-15−/− animals mucosally infected with the identical virus contained an equivalent frequency of NP-specific CD8 Tmem in all sites examined, despite a lower response magnitude overall (Fig. 3). Thus, altering the route of infection with the same virus concordantly altered the requirement of IL-15 for the development of Ag-specific CD8 Tmem cells.

Figure 3. Differential requirement for IL-15 in the development and maintenance of CD8 Tmem generated by a systemic vs. mucosal infection.

The mean percent VSV-NP-Tet+ among CD8+ T cells in the indicated tissues (A) are plotted (B) for systemically (104 pfu VSV i.v.) infected WT (black bars) or IL-15−/− (open bars) and mucosally (104 pfu VSV i.n.) infected WT (darkly shaded bars) or IL-15−/− (lightly shaded bars) are plotted ± SEM (n=4-5 mice/group) on day 30 p.i.. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

We were surprised to find an equal preservation of CD8 Tmem in the secondary lymphoid tissues of IL-15−/− mice infected i.n. with either influenza or VSV. One might speculate that altering infection route favors the development of either Tem or Tcm, which could be differentially dependent on IL-15 for survival. Comparing systemic to intranasal VSV infection, the ratio of splenic NP-specific Tcm : Tem shifted from 20:80 to 40:60 (data not shown). While the overall alteration in Tmem subsets could be due to differences in Ag load (20), IL-15−/− mice generated ratios of Tmem subsets equivalent to WT regardless of the route of infection. While IL-7 can redundantly substitute for IL-15 (2,21), we did not observe any differences in CD127 expression on Tmem, and we also failed to observe any differences in CD122 expression on circulating Tmem in the absence of IL-15 (data not shown). Therefore, IL-15-independent Tmem generated after mucosal infection are not the result of alterations in the development of a particular Tmem subset nor CD122 expression, but are more likely due to a unique priming environment which bestows a homeostatic program on the Tmem that is IL-15-independent.

Additionally, the harsh regulatory environment of the lung airways might render this site incapable of sustaining CD8 Tmem. Mucosal immune responses require extensive regulation of immune activation to prevent immunopathology. Thus, the mucosal environment stringently regulates the type, level, and duration of cytokines and chemokines elicited by mucosal infections in order to activate, recruit, and ultimately sustain (perhaps at set numerical thresholds) the appropriate lymphocytes at these sites. Our experiments contrasting the differential requirement for IL-15 in systemic vs mucosally administered VSV illustrate this phenomenon. While systemically there may be a need to maintain large numbers of VSV-specific CD8 Tmem, the regulatory mechanisms in place in the lung could be sufficient to inhibit the maintenance of memory cells beyond a certain threshold, regardless of IL-15 availability. Thus, while adjuvanting IL-15 could prolong CD8 Tmem responses to systemic infections, such regimens may have limited benefit in sustaining differentiated respiratory-derived CD8 Tmem.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the University of Georgia and the National Institutes of Health (AI077038 and AI081800 to K.D.K.)

References

- 1.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nri778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan JT, Ernst B, Kieper WC, LeRoy E, Sprent J, Surh CD. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-7 jointly regulate homeostatic proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ cells but are not required for memory phenotype CD4+ cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1523–1532. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schluns KS, Williams K, Ma A, Zheng XX, Lefrancois L. Cutting edge: requirement for IL-15 in the generation of primary and memory antigen-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:4827–4831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wherry EJ, Becker TC, Boone D, Kaja MK, Ma A, Ahmed R. Homeostatic proliferation but not the generation of virus specific memory CD8 T cells is impaired in the absence of IL-15 or IL-15Ralpha. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;512:165–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0757-4_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker TC, Wherry EJ, Boone D, Murali-Krishna K, Antia R, Ma A, Ahmed R. Interleukin 15 is required for proliferative renewal of virus-specific memory CD8 T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1541–1548. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller SN, Langley WA, Li G, Garcia-Sastre A, Webby RJ, Ahmed R. Qualitatively different memory CD8+ T cells are generated after lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and influenza virus infections. J Immunol. 2010;185:2182–2190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang S, Mozdzanowska K, Palladino G, Gerhard W. Heterosubtypic immunity to influenza type A virus in mice. Effector mechanisms and their longevity. J Immunol. 1994;152:1653–1661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hogan RJ, Usherwood EJ, Zhong W, Roberts AA, Dutton RW, Harmsen AG, Woodland DL. Activated antigen-specific CD8+ T cells persist in the lungs following recovery from respiratory virus infections. J Immunol. 2001;166:1813–1822. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ely KH, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. Cutting edge: effector memory CD8+ T cells in the lung airways retain the potential to mediate recall responses. J Immunol. 2003;171:3338–3342. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ely KH, Cookenham T, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. Memory T cell populations in the lung airways are maintained by continual recruitment. J Immunol. 2006;176:537–543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verbist KC, Cole CJ, Field MB, Klonowski KD. A role for IL-15 in the migration of effector CD8 T cells to the lung airways following influenza infection. J Immunol. 2011 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002613. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, Matsuki N, Charrier K, Sedger L, Willis CR, Brasel K, Morrissey PJ, Stocking K, Schuh JC, Joyce S, Peschon JJ. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–780. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubois S, Mariner J, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. IL-15Ralpha recycles and presents IL-15 In trans to neighboring cells. Immunity. 2002;17:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubinstein MP, Lind NA, Purton JF, Filippou P, Best JA, McGhee PA, Surh CD, Goldrath AW. IL-7 and IL-15 differentially regulate CD8+ T-cell subsets during contraction of the immune response. Blood. 2008;112:3704–3712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-160945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanjabi S, Mosaheb MM, Flavell RA. Opposing effects of TGF-beta and IL-15 cytokines control the number of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hikono H, Kohlmeier JE, Takamura S, Wittmer ST, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. Activation phenotype, rather than central- or effector-memory phenotype, predicts the recall efficacy of memory CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1625–1636. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandau MM, Kohlmeier JE, Woodland DL, Jameson SC. IL-15 regulates both quantitative and qualitative features of the memory CD8 T cell pool. J Immunol. 2010;184:35–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stemberger C, Neuenhahn M, Buchholz VR, Busch DH. Origin of CD8+ effector and memory T cell subsets. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:399–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.