Abstract

We report the results of sequence analysis and chromosomal distribution of all distinguishable long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (Cer elements) in the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Included in this analysis are all readily recognizable full-length and fragmented elements, as well as solo LTRs. Our results indicate that there are 19 families of Cer elements, some of which display significant subfamily structure. Cer elements can be clustered based on their tRNA primer binding sites (PBSs). These clusters are in concordance with our reverse transcriptase- and LTR-based phylogenies. Although we find that most Cer elements are located in the gene depauperate chromosome ends, some elements are located in or near putative genes and may contribute to gene structure and function. The results of RT-PCR analyses are consistent with this prediction.

Retrotransposons are an abundant and widely distributed class of mobile repetitive elements that transpose through an RNA intermediate (Berg and Howe 1989). A significant portion of eukaryotic genomes examined to date is comprised of retrotransposons. For example, more than half of the maize (>50%, SanMiguel et al. 1996) and wheat (>90%, Flavell 1986) genomes as well as ∼40% of the human genome (Yoder et al. 1997) is made up of retrotransposons. Long recognized as a major source of mutation (Green 1988) and disease (Miki 1998), retrotransposons have been implicated in the evolution of genome structure and function as well (e.g., McDonald 1995a,b; Britten 1997; Brosius 1999).

Genome sequencing of a variety of organisms is providing an unprecedented opportunity to study the evolutionary history of retrotransposons and their contribution to genome structure and function. For example, recent surveys of retrotransposons within the Caenorhabditis elegans genome have revealed the presence of no fewer than 19 families of long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (Bowen and McDonald 1999; Malik et al. 2000; Frame et al. 2001), including two families (Cer7 and Cer13) which display features characteristic of infectious retroviruses (Bowen and McDonald 1999).

We extend these findings by analyzing the sequence and identifying the chromosomal distribution of all distinguishable Cer LTR retrotransposon sequences present in the C. elegans genome. In our analysis we group all distinguishable Cer elements into three distinct types: (1) full-length elements containing all of the characteristic features of LTR retrotransposons including putative gag, pol and, in some cases, env genes flanked by LTRs; (2) partially deleted or fragmented elements which are missing one or more of the characteristic features of full-length elements; and (3) solo LTRs which are believed to be the products of recombination events between the flanking LTRs of full-length elements (Berg and Howe 1989). Our results indicate that there are 19 Cer families represented within the sequenced (N2) C. elegans genome. All 19 families are either the gypsy/Ty3 or Bel class of retrotransposons. No copia/Ty1 type elements are present in the C. elegans genome.

Although some full-length Cer elements were found to be members of extended families with well defined evolutionary histories, others appear to be single-element families with no detectable lineage within the (N2) genome. In contrast, several families of Cer elements were identified that are comprised of fragmented elements or solo LTRs exclusively. Cer elements can be grouped according to their tRNA binding sites into multiple clusters which are consistent with our reverse transcriptase (RT)- and LTR sequence-based phylogenies. We have also analyzed the inter- and intrachromosomal distribution of Cer elements in the N2 genome. Although most Cer elements are located in the gene depauperate chromosomal ends, some elements are located in or near putative genes and may have contributed to gene structure and function. The results of RT-PCR analyses are consistent with this prediction. Products consistent with processing of these transcripts and removal of predicted introns were observed. Cer LTR sequence could account for at least 12% to as much as 54% of the coding region within mRNAs transcribed from these loci.

RESULTS

The C. elegans Genome Consists of at Least 19 Families of LTR Retrotransposons

Closely related groups of full-length Cer LTR retrotransposons display >90% amino acid similarity among their respective reverse transcriptases (RTs) and have been designated as families (Bowen and McDonald 1999). Using this criterion, full-length LTR retrotransposons representing 12 distinct families have been described previously in C. elegans, Cer1–Cer12 (Bowen and McDonald 1999). By searching for homology to envelop (ENV) proteins, Malik et al. (2000) discovered two additional families (Cer13 and Cer14). More recently, Frame et al. (2001) identified six additional putative families. In the present study, we include fragmented elements and solo LTRs in our analysis to add substructure to the Cer phylogenetic tree. Using this approach, we independently identified a total of 19 families (Cer1–Cer19) of Cer elements within the essentially complete (>99%) N2 C. elegans genome (C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998).

The number of Cer elements within families varies considerably (Table 1). In general, full-length Cer elements are in relatively low abundance within the C. elegans genome. Only two of the 19 families (Cer9 and Cer20) contain three full-length elements, whereas three families (Cer8, 15, and 16) contain two, and 12 families (Cer1–Cer7, and Cer10, 12, 13, 17, and 19) contain only one. Two families (Cer11 and Cer14) contain no full-length elements, and another two families are comprised of only a single full-length element (Cer4 and Cer17). Fragmented elements are also in relatively low abundance (<4 per family) in 15 of the 19 families (Cer2, 3, 5–7, 9–16, 19, and 20). Solo LTRs were detected in 13 of the 19 families (solo LTRs lacking in Cer4, 7, 11, 13, 14, and 17) ranging in number from 12 to 1 per family. Five of the families displayed subfamily structure. While members of Cer element families share >90% RT sequence identity, within family sequence identity values among the more rapidly evolving LTRs are more variable, ranging from 60 to 100% (Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Number of Full-Length, Fragmented, and Solo LTRs in the Sequenced C. elegans (N2) Genome

| Cer Element | Full-length | Fragment | Solo LTR | Subtotals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cer1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Cer2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Cer2-1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Cer3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cer3-1 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 11 |

| Cer4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cer5 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 14 |

| Cer6 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| Cer7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Cer8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Cer9 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 11 |

| Cer10 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| Cer11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cer12 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 11 |

| Cer12-1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Cer 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Cer 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cer15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Cer15-1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Cer16 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Cer16-1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Cer16-2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Cer 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cer 19 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 |

| Cer 20 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| Totals | 20 | 24 | 61 | 124 |

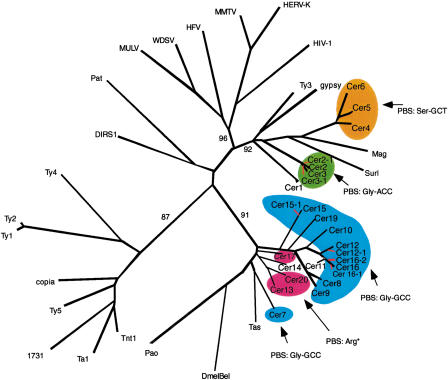

Figure 1.

Composite RT/LTR phylogenetic analysis of Cer elements. Shown is an unrooted NJ phylogram of RT (amino acid) and LTR (nucleotide) sequences. RT amino acid alignments were used to establish family structure (black); LTR nucleotide sequences were added to establish subfamily structure (red). tRNA primer binding sites (PBSs) are highlighted to show conservation of tRNA priming across families. Alignments were produced via MacVector (http://www.gcg.com) and ClustalX 1.8 (Thompson et al. 1997). * PBS reported by Frame et al. (2001).

Table 2.

List of All Known Cer LTR Retrotransposons in the Sequenced C. elegans(N2) Genome

| Element family | Genomic clone | Element type | Chromosome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cer1 | f44e2/par3 | full | III |

| Cer1 | c25a11 | ltr | X |

| Cer1 | c24h10 | ltr | X |

| Cer1 | y39e4b | ltr | III |

| Cer2 | r03d7 | full | II |

| Cer2 | f53e10 | ltr | V |

| Cer2-1 | k08d10 | frag | IV |

| Cer2-1 | f49f1 | frag | IV |

| Cer2-1 | w04a8 | ltr | I |

| Cer3 | f58h7 | full | IV |

| Cer3-1 | y37h2a | frag | V |

| Cer3-1 | y76b12c | ltr | IV |

| Cer3-1 | y39e4a | ltr | III |

| Cer3-1 | k09h9 | ltr | I |

| Cer3-1 | y39b6a | ltr | V |

| Cer3-1 | e02h9 | ltr | III |

| Cer3-1 | y105e8e | ltr | I |

| Cer3-1 | y23h5b | ltr | I |

| Cer3-1 | y77e11a | ltr | IV |

| Cer3-1 | y75b8a | ltr | III |

| Cer3-1 | t09a5 | ltr | II |

| Cer4 | f15g10/t23e7 | full | X |

| Cer5 | t03f1 | full | I |

| Cer5 | f39b3 | frag | X |

| Cer5 | k02a2 | frag | II |

| Cer5 | c31e10 | frag | X |

| Cer5 | f22g12 | frag | I |

| Cer5 | r01h5 | ltr | X |

| Cer5 | y27f2a | ltr | II |

| Cer5 | t27f6 | ltr | I |

| Cer5 | c25b8 | ltr | X |

| Cer5 | f49c8 | ltr | IV |

| Cer5 | f22e5 | ltr | II |

| Cer5 | w04g5 | ltr | I |

| Cer5 | y111b2g | ltr | III |

| Cer5 | f56h6 | ltr | I |

| Cer6 | e03a3 | full | III |

| Cer6 | y102a5c | frag | V |

| Cer6 | y53f4a | ltr | II |

| Cer6 | y73f8a | ltr | IV |

| Cer6 | zc487 | ltr | V |

| Cer6 | c55a1 | ltr | V |

| Cer7 | zc132 | full | V |

| Cer7 | h08m01 | ltr | IV |

| Cer8 | zk262/zk228 | full | V |

| Cer8 | c03a7 | full | V |

| Cer8 | c33e10 | ltr | X |

| Cer9 | y43f4a | full | III |

| Cer9 | w09b7/f07b7 | full | V |

| Cer9 | f07b7/k06c4 | full | V |

| Cer9 | k09e3 | frag | X |

| Cer9 | c33c12/c40a11 | frag | II |

| Cer9 | c07d8/c56g3 | frag | X |

| Cer9 | b0047 | ltr | II |

| Cer9 | c13b9 | ltr | III |

| Cer9 | y59a8b | ltr | V |

| Cer9 | y57a10a | ltr | II |

| Cer9 | f15a2 | ltr | X |

| Cer10 | y81b9a/c35b8 | full | X |

| Cer10 | t23b12/zk994 | frag | V |

| Cer10 | t12b5 | ltr | III |

| Cer10 | y73f8a | ltr | IV |

| Cer10 | t22b2 | ltr | X |

| Cer11 | t14g12 | frag | X |

| Cer12 | f21d9/f55c9 | full | V |

| Cer12 | k07c6 | ltr | V |

| Cer12 | w03g1 | ltr | IV |

| Cer12 | y51h4a | ltr | IV |

| Cer12 | c01b9 | ltr | II |

| Cer12 | c09g1 | ltr | X |

| Cer12 | k04c1 | ltr | X |

| Cer12 | c44b12 | ltr | IV |

| Cer12 | y94h6a | ltr | IV |

| Cer12 | c04g6 | ltr | II |

| Cer12 | y60a3a | ltr | V |

| Cer12-1 | zc15 | frag | V |

| Cer12-1 | f41g4 | frag | X |

| Cer12-1 | k08d12 | ltr | IV |

| Cer12-1 | f58f6 | ltr | IV |

| Cer13 | y75d11a/w03h1 | full | X |

| Cer13 | c09b9 | frag | IV |

| Cer14 | y105c5b | frag | IV |

| Cer15 | y102a5d/f40d4 | full | V |

| Cer15 | t11f9 | frag | V |

| Cer15 | y105e8a | ltr | I |

| Cer15-1 | c52e2/c16c4 | full | II |

| Cer15-1 | f19b2 | frag | V |

| Cer15-1 | y40h7a | frag | IV |

| Cer15-1 | y45f10c | ltr | IV |

| Cer16 | r13d11 | full | V |

| Cer16 | f47d2 | ltr | V |

| Cer16 | f28d9 | ltr | I |

| Cer16 | f36a4 | ltr | IV |

| Cer16-1 | y71h2am | ltr | III |

| Cer16-1 | f38c2 | ltr | IV |

| Cer16-1 | f11a6 | ltr | I |

| Cer16-1 | y32h12a | ltr | III |

| Cer16-1 | f47b7 | ltr | X |

| Cer16-1 | f20b4 | ltr | X |

| Cer16-2 | f20b4/6r55 | full | X |

| Cer16-2 | zk1025/c27c7 | frag | I |

| Cer16-2 | t16g12 | frag | III |

| Cer16-2 | t05a1 | frag | IV |

| Cer16-2 | zc247 | ltr | I |

| Cer17 | r52 | full | II |

| Cer19 | r09h3/c36c9 | full | X |

| Cer 19 | c38d9 | frag | V |

| Cer 19 | y7a5a | ltr | X |

| Cer 19 | f15d4 | frag | II |

| Cer 19 | t06a10 | frag | IV |

| Cer 19 | d1022 | ltr | II |

| Cer 19 | f35h10 | ltr | IV |

| Cer 19 | zk1055 | ltr | V |

| Cer 19 | c35d6 | ltr | IV |

| Cer 19 | t08g3 | ltr | V |

| Cer 19 | zk643 | ltr | III |

| Cer 20 | y87g2a | full | I |

| Cer 20 | k01d12 | full | V |

| Cer 20 | f41b5 | full | V |

| Cer 20 | y50e8a | frag | V |

| Cer 20 | t10g3 | ltr | V |

| Cer 20 | t28d6 | ltr | III |

| Cer 20 | c32b5 | ltr | II |

| Cer 20 | y94h6a | ltr | IV |

Genomic clone ID and chromosome locations were obtained from Wormbase (http://www.wormbase.org).

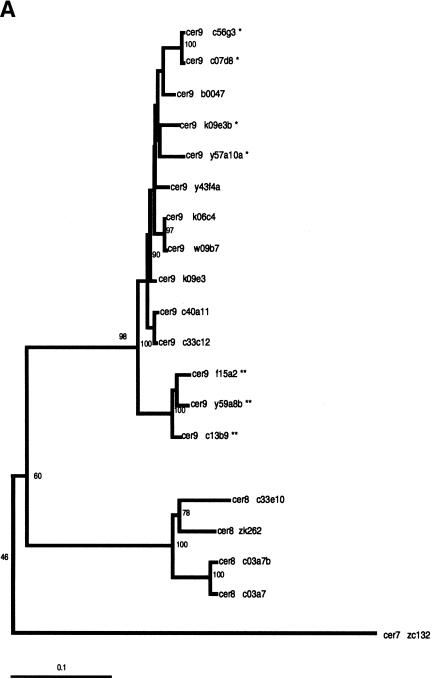

Six of the eight solo LTRs or LTR-containing fragments within the Cer9 family were found to contain an ∼100-bp sequence inserted into the center of their 3′ LTRs (c56g3/c07d8, y57a10a, and k09e3 contain a 108 bp insert; f15a2, y59a8b, and c13b9 contain a 106 bp insert). Interestingly, none of the three Cer 9 full-length elements contain either insert within their LTRs. The ∼100-bp inserts in these LTRs share 85% identity among themselves but display no significant homology to other sequences within the C. elegans (N2) genome. Aside from this size polymorphism, all of the Cer9 family members share a remarkable 95% LTR nucleotide sequence identity with one another.

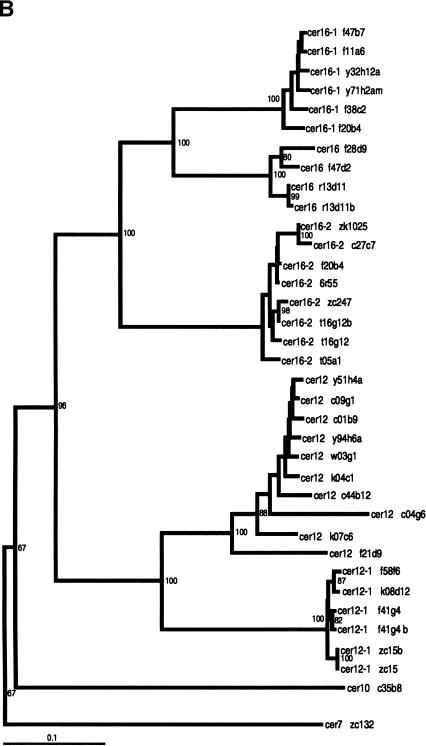

Whereas the slowly evolving RT encoding region of LTR retrotransposons is ideal for quantitating evolutionary distances among even distantly related families of retroelements (Flavell 1986; Xiong and Eickbush 1990), analysis of differences among the more rapidly evolving LTRs is better suited for the identification of phylogenetic substructure within families of LTR retrotransposons. Phylogenetic trees based on Cer element LTR sequences reveal the presence of significant substructure within several Cer element families. Both neighbor-joining and parsimony criteria support the existence of distinct subgroups in the Cer2, 3, 12, 15, and 16 families of elements. For example, the Cer 12 family is comprised of 15 elements (primarily solo LTRs) falling into two distinct subfamilies, whereas the 14 elements comprising the Cer16 family of elements fall into three distinct subfamilies (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic trees of subfamily structure based on LTR nucleotide sequence data. LTRs from full, fragmented, and solo LTR elements were aligned via ClustalX 1.8 (Thompson et al. 1997), and the NJ method was used to construct trees. Insertions/deletions were ignored. Values on individual branches are bootstrap percentages based on 1000 bootstrap repetitions. Each LTR in the tree is named by the genomic clone in which it was found. For elements with two LTRs, the 3′ LTR is labeled by a lower case “b” following the clone number. Each tree is shown with a scale bar determined by the number of nucleotide substitutions per site between two sequences. (A) Phylogenetic tree displaying substructure within Cer8 and Cer9 families, with Cer7 as the outgroup. The tight branching of the tree demonstrates the high sequence identity shared among Cer9 family members. * indicates the presence of a ∼108 bp insert in the center of Cer9 LTR; ** indicates the presence of a ∼106 bp insert in the center of the Cer9 LTR. Both inserts are >85% identical. (B) Phylogenetic tree displaying substructure within Cer12 and Cer16 families, with Cer7 as the outgroup. Cer12 consists of two subfamilies (Cer12 and 12-1); Cer16 has three subfamilies (Cer16, 16-1, and 16-2). The tight clustering seen in both families represents a high degree of nucleotide identity between elements within a subfamily.

Cer Element Families Share tRNA Primers

RT requires a primer strand to initiate minus-strand DNA synthesis. Host-encoded tRNA is the primer used by most retroviruses and LTR retrotransposons analyzed to date (Telsnitsky and Goff 1997). In the process of priming, the native tRNA molecule is partially unfolded such that 18 bp at its 3′ terminus is free to base pair with a complementary sequence, termed the primer binding site (PBS), on the retroviral or LTR retrotransposon RNA. Different tRNA primers are known to be used by different families of retroviruses and LTR retrotransposons and have been used as an indicator of evolutionary relationships (Vogt 1997).

Primer binding sequences are located just 3′ of the proviral 5′ LTR. Utilizing the C. elegans tRNA gene database (http://rna.wustl.edu/GtRDB/Ce/), we identified putative Cer primer binding sites by FASTA searches of 100 nucleotides downstream of the 5′ LTR of full-length Cer elements. Consistent with the recent observations of Frame et al. (2001), we found that full-length elements representing Cer families in the Cer7/BEL clade share a binding site for the Gly-GCC-type (Cer7–10, 12, 15, 16, and 19) or for Arg-type tRNAs (Cer13, 17, and 20). We also confirm the observation of Frame et al. (2001) that Cer7 encodes its own 71 bp Gly-GCC-type tRNA (CE-CHRV-1298_TRNA5-GLYGCC; Fig. 1).

Extending our alignment of putative PBSs and FASTA searches of the tRNA database to the Ty3/gypsy clade revealed that Cer2 and Cer3 share a PBS for Gly-ACC tRNA. In contrast, we found that Cer4, Cer5, and Cer6 share a Ser-GCT tRNA. Cer1 displays weak homology to the PBS for Thr-GGT-type tRNA.

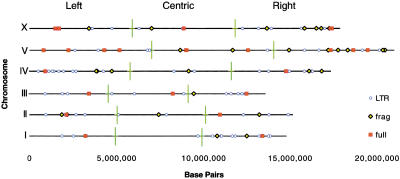

Most Cer Elements are Located at Chromosome Ends

The chromosomal position of each Cer element was used to analyze the distribution of Cer elements throughout the genome. To test for interchromosomal clustering of Cer elements, we employed the Kolmogov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit test (Zarr 1999) to look for a deviation from a random distribution of elements among chromosomes. The results indicate no significant deviation from the null hypothesis (P = 0.91). The distribution of individual families of Cer elements (Cer3, 5, 9, and 12) and family groups (Cer8 and Cer9, P = 0.046; Cer12 and Cer16, P = 0.51; Cer2 and Cer3, P = 0.13) were tested separately and also found to be distributed randomly among chromosomes.

Tests were carried out to determine whether the distribution of Cer elements on individual chromosomes was also random. Our analysis rejected the random distribution hypothesis for all chromosomes except chromosome III (Fig. 3). Chromosomes I, II, IV, V, and X were found to display nonrandom clustering of Cer elements on their chromosomal ends. This is consistent with a previous report that DNA transposable elements in C. elegans are clustered at chromosome ends (C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998; Surzycki and Belknap 2000) and the observation that the middle third of C. elegans chromosomes are “gene rich.” The ends of C. elegans chromosomes display a lower gene density and are associated with relatively high rates of recombination (Barnes et al. 1995; Wilson 1999).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Cer full-length, fragmented and solo LTR element sequences in the C. elegans genome. A genomic coordinate value for all Cer elements was calculated (see Methods) and elements plotted to their respective chromosome location. Chromosomes were divided into three regions (left, center, right). All chromosomes except chromosome III display significant clustering outside of the centric genic region. Cer elements are randomly distributed across chromosomes.

Cer Elements May Contribute to C. elegans Gene Function

The results of our genomic positioning of Cer elements indicates that a number of these elements lie within or proximal to genes. Previous studies of LTR retrotransposons in a variety of plant and animal species have revealed that these elements may be coopted for a variety of host gene functions, including promoter, splicing, and terminator activities (e.g., Britten 1997; Medstrand et al. 2001). In an initial effort to determine whether Cer elements contribute to gene function, we screened C. elegans EST databases (dbEST-C. elegans) for homology to Cer elements. ESTs with significant homology to Cer LTRs were identified. The complete sequences of these ESTs were BLASTed against the C. elegans genome database to identify the clones containing the Cer LTRs and associated putative genes (F20B4, C56G3, 6R55, and F53E10).

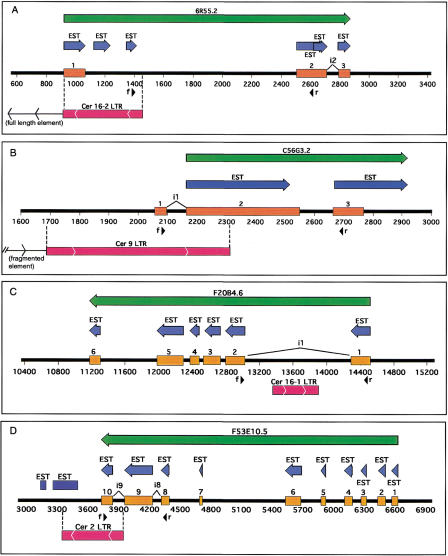

The specific region of Cer element identity within the four clones (F20B4.6, C5663.2, 6R55.2, and F53E10.5) was overlaid on the existing annotation of each region. Our results indicate that these Cer elements are part of putative genes (Fig. 4). Although all four gene regions are putative in nature, they retain strong predictive computational support. In addition, multiple ESTs were found to map to the exon regions of these putative genes, adding further support. The results of TBLASTN searches indicate that two of the sites (F20B4.6 and C56G3.2) displayed significant homology (outside the Cer element sequence) to previously characterized genes. F20B4.6 exhibits homology with genes encoding ceramide glucosyl transferases; C56G3.2 displays homology with genes encoding aldo/keto reductases. The putative genes contained in regions 6R55.2 and F53E10.5 show no homology with genes thus far characterized (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Cer element LTRs are part of some C. elegans genes. Green arrows represent Wormbase-predicted gene regions with corresponding identification. Blue arrows depict ESTs concordant to the predicted gene region. Orange boxes are predicted exon regions. Red boxes denote LTR position, and internal arrows indicate direction. The black line and numbers represent position along the genomic clone sequence (F20B4, C56G3, 6R55, F53E10). Black arrows indicate direction and location of forward (f) or reverse(r) PCR primers. For visual simplicity, only introns (i#) discussed in the text are displayed above and between exons. (A) An entire LTR from the 5′ end of a full-length Cer16-2 element is part of the 5′ end of a putative C. elegans gene (6R55.2) of unknown function. (B) The Cer9 LTR overlaps two exons of an aldo/keto reductase homolog in C. elegans (C56G3.2). The LTR is the 3′ end of a fragmented Cer9 element. (C) A Cer16-1 solo LTR is part of intron 1 of a C. elegans gene (F20B4.6) in the glucosyltransferase family. (D) A Cer2 solo LTR constitutes the 3′ end of a putative C. elegans gene (F53E10.5) of unknown function.

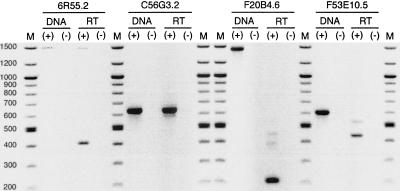

Transcribed and Processed mRNAs Contain Cer LTR Sequence

A series of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR) were performed to test the hypothesis that Cer elements contribute to the structure and function of some C. elegans genes. Sets of primers were designed to amplify predicted gene transcripts containing Cer element sequences. Because nascent RNA transcripts are typically in low abundance in standard RNA preparations, they are often underrepresented or undetectable in the products of RT-PCR reactions. For this reason, PCR of genomic DNA was also carried out for each set of primers as a positive control.

Primers designed for the 6R55.2 gene yielded RT-PCR products consistent with the expected sizes of the nascent (1514 bp) and processed (429 bp) transcripts (Fig. 5). A 6R55.2 transcript fully processed according to its predicted gene structure (Fig. 4A) would contain 16% LTR sequence from a Cer16-2 element in its coding region. If all exons represented by EST alignments (Fig. 4A) were present in the final processed transcript, 54% of its coding region would be LTR sequence.

Figure 5.

PCR/RT-PCR analysis of C. elegans genes containing Cer LTR sequence showing the production of spliced, polyadenylated transcripts from these loci. A negative image is presented for visual clarity. Within a locus, PCR (control) and RT-PCR were performed using the same primer set. DNA (+) and DNA (−) indicate PCR reactions with and without nematode genomic DNA, respectively. RT (+) and RT (−) indicate RT-PCR reactions with and without reverse transcriptase, respectively. M = 100 bp ladder.

Primers designed for the C56G3.2 gene yielded RT-PCR products consistent with the expected size of the nascent (634 bp) and processed (569 bp) transcripts (Fig. 5). The smaller RT-PCR product is consistent with excision of the intron predicted within the Cer9 LTR. It is intriguing to note that the position of the predicted intron within the Cer9 LTR overlaps with an approximate 100bp sequence missing in some of the solo LTRs identified in this study. A 6R55.2 transcript fully processed according to its predicted gene structure (Fig. 4B) would have first and second exons comprised of 100% and 40% of Cer9 LTR sequence, respectively. Thus, within its coding region the mRNA would be 36% LTR sequence. Alternate intron/exon structures (Fig. 4B) could generate transcripts ranging from 20% to 48% Cer9 LTR as mRNA coding sequence.

Primers designed for the F20B4.6 gene yielded a preferentially amplified RT-PCR product of ∼213 bp. This product is consistent with excision of the Cer16-1 LTR from intron 1 (Fig. 4C, Fig. 5), although potential enhancer activity of the LTR cannot be excluded by this analysis. Two bands at ∼380 and ∼430 bp may represent unpredicted processing products or nonspecific priming, although they were also apparent in reactions performed at temperatures 10°C higher than the predicted optimum for the pair (data not shown).

Primers designed for the F53E10.5 yielded two RT-PCR products consistent with predicted processing of the nascent transcript (Fig. 5). A weakly amplified product at ∼520 bp is consistent with mRNA processing and removal of intron 9 (Fig. 4D). The preferentially amplified product at ∼449 bp is consistent with removal of introns 8 and 9. Exon 10, derived entirely from Cer2 LTR DNA, would contribute 12% coding sequence if the mRNA was fully processed as predicted.

In summary, RT-PCR analyses demonstrated that the inserted Cer elements were part of each gene transcript, thus providing molecular confirmation of our computational results (Fig. 5). Polyadenylated transcripts composed of retroelement sequence were produced from the three genes in which elements were part of the coding region. Furthermore, products consistent with processing of these transcripts and removal of predicted introns were observed.

DISCUSSION

The C. elegans Genome Contains Relatively Few Families of LTR Retrotransposons with Unusual Subfamily Structure

Nucleotide sequence divergence among LTR retrotransposons can be used to establish phylogenetic relationships and other relevant information related to retrotransposon evolution. Our approach has been to utilize RT sequence to establish families (defined as groups of LTR retrotransposons sharing at least 90% RT sequence homology) and to subsequently utilize the divergence among the more rapidly evolving LTRs to establish subfamily structure. An alternative approach recently employed by Frame et al. (2001) to characterize the BEL-like class of C. elegans LTR retrotransposons, is to base phylogenetic relationships primarily on LTR sequences. A priori, both approaches might be expected to give similar results. However, because the C. elegans genome contains relatively few full-length elements and relatively more fragmented elements and solo LTRs lacking RT sequences, the former approach will tend to identify fewer families of elements with more substructure than the latter approach. For example, the Cer16 and Cer18 families described by Frame et al. (2001) are collapsed in our analysis to a single family (Cer16) with detailed subfamily structure. As more data become available on the diversity of LTR retrotransposons present in other strains of C. elegans, the results should converge on a single picture of the evolutionary history of Cer elements.

Although our view of the phylogenetic structure of Cer elements differs somewhat from that described by Frame et al. (2001), we find that many of the general features of the Cer 7/BEL class of C. elegans LTR retrotransposons described by those authors hold true for the Ty3/gypsy class as well. In general, the C. elegans genome appears to have a relatively low tolerance for LTR retrotransposons (<1%). Whereas we have identified 124 full-length, fragmented, or solo LTR Cer elements in the sequenced (N2) C. elegans genome, >350 LTR retrotransposon elements have been described in the yeast Candida albicans (Goodwin and Poulter 2000) and >300 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Kim et al. 1998), both species with genomes nearly an order of magnitude smaller than C. elegans (C. elegans Sequencing Consortium 1998).

Single-element groups add to the puzzle. Families represented by only one element (Cer 4, Cer11, and Cer17) have no detectable history in the C. elegans (N2) genome, suggesting that they may have been introduced by horizontal transfer. The fact that the Cer7 and Cer14 elements encode a putative env gene is consistent with the hypothesis that at least some Cerelements may have entered the N2 genome via horizontal transfer. However, additional information on the diversity of elements in other C. elegans strains and related Caenorhabditis species will be necessary to definitively test the horizontal transfer hypothesis.

A number of solo LTRs and LTR-containing fragments are nearly identical in sequence despite the fact that related full-length putative progenitor elements are not present in the genome. For example, the Cer3-1 subfamily consists of 10 solo LTRs and one LTR-containing fragment with >94% identity. Similarly, the Cer16-1 subfamily consists of six solo LTRs with >94% identity. Despite the sequence similarity among these and other subfamily LTRs, the sequences of Cer16-1 LTRs are distinctly different from their most closely related full-length elements. One possible explanation of this apparent paradox is that some mechanism exists in C. elegans to rapidly remove full-length transposable elements, as has been postulated in Drosophila (Petrov et al. 1996). Under this scenario, solo LTRs and LTR-containing fragments are remnants of degraded full-length elements. Alternatively, the high sequence similarity existing among families of solo LTRs and LTR-containing fragments may be the product of gene conversion.

A third possible explanation is that at least some of the families of solo LTRs and LTR-containing fragments represent footprints of double-strand break (DSB) repair events (Garfinkel 1997; Haber 2000). Teng et al. (1996) and Yu and Gabriel (1999) reported that a variety of Ty1 LTR transcription intermediates have been used to repair double-stranded breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. If such a mechanism exists in C. elegans, it is possible that at least some subfamilies of LTRs displaying high sequence similarity were copied off of the same master element during the process of DSB repair.

The Presence of tRNA Genes in Cer Elements May Be of Adaptive Significance

Putative tRNA PBSs have been identified for most full-length Cer elements. Matching tRNAs consist predominantly of glycine (TCC and ACC) types. The distribution of these different types of tRNA binding sites was found to be consistent with our RT-based phylogeny (Fig. 1).

It is interesting to speculate about the significance of the surprising finding that a complete tRNA-Gly gene is located within the untranslated leader region of Cer7. The observation that LTR retrotransposons are common in heterochromatic regions of genomes (Dimitri and Junakovic 1999) has led to the speculation that the evolutionary origin of heterochromatin was as a defense mechanism against transposable elements (e.g., McDonald 1999; Henikoff 2000). tRNA genes are known to exclude nucleosomes and limit the spread of heterochromatin (Morse 2000). Thus, the inclusion of a tRNA gene in an LTR retrotransposon may provide a selective advantage to an element located in heterochromatic regions by preventing nucleosome positioning. The consequent exclusion of surrounding chromatin may permit access of transcription factors to promoter sequences within the LTR and adjacent leader regions that would otherwise be inaccessible. Although the C. elegans genome does not contain constitutive heterochromatin, transient heterochromatin-like structures occur during development (e.g., Jedrusik and Schulze 2001). As analyses of LTR retrotransposons are extended to additional plant and animal species, it will be interesting to see if the presence of complete tRNA genes in untranslated leader regions is a general feature of some families of LTR retrotransposons.

Cer Elements May Contribute to C. elegans Gene Structure and Function

There is a growing body of evidence that transposable elements play an important role in genome evolution by contributing to the structure and/or function of genes (e.g., McDonald 1995a,b; Britten 1997; Medstrand et al. 2001). For example, there are >100 reported examples of essential gene structures and functions in mammals that are attributable to retrotransposons or retrotransposon-derived sequences (Brosius 1999; see also http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Makalowski/ScrapYard/). LTRs are known to possess promoter, polyadenylation, and enhancer functions (e.g., Medstrand et al. 2001; Britten 1997). For this reason, LTR retrotransposon insertions in or near genes have been postulated to be a significant factor in regulatory evolution in both plants and animals (e.g., McDonald 1993, 1995a). The insertion of transposable elements in or near introns can result in alternative splicing patterns. Such events are also believed to have contributed to gene evolution (e.g., Kapitonov and Jurka 1999). The insertion of transposable elements into the coding region of genes is typically associated with loss of gene function (Green 1988). However, occasionally such events are associated with alterations in gene sequence which may contribute to the evolution of new gene functions (e.g., Banki et al. 1994).

In an initial effort to address the possible contribution of Cer elements to C. elegans gene evolution, we screened C. elegans EST databases for the presence of Cer element LTRs. We identified four genes in which Cer elements may be involved in gene function. In three cases, LTR sequences appear to be incorporated into coding regions (Fig. 4A, B, D). In addition, we found that Cer LTRs map to putative gene splice acceptor/donor sequences and termination regions of genes (Fig. 4A, B, C). These results are intriguing and suggest that Cer LTRs may influence gene regulation and expression in the C. elegans N2 strain.

RT-PCR analyses confirmed that mRNAs containing Cer LTR sequence are actively transcribed from these loci. In three of the four loci, Cer element sequences mapped to coding regions of the genes. For each of these cases, polyadenylated transcripts were shown to be produced containing the expected Cer LTR (Fig. 5). Furthermore, products consistent with processing of these transcripts and removal of predicted introns were also observed. Cer LTR sequences could account for at least 12% to as much as 54% of the coding region within mRNAs transcribed from these loci.Detailed molecular analyses are currently underway in our laboratory to precisely define the contribution of Cer elements to the function of these genes in the N2 strain and to examine the functional significance of Cer element insertional polymorphisms at these and other loci among C. elegans strains.

METHODS

Sequence Identification and Retrieval

Sequence retrieval was initiated by performing BLASTN searches (default parameters; Altschul et al. 1997) against the Wormbase (http://www.wormbase.org) and GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) databases using LTRs representing each previously identified family of Cer elements (Bowen and McDonald 1999; Malik et al. 2000). To insure that all families of Cer LTRs were identified, we employed an iterative approach whereby LTR sequences with relatively low homology (∼70%) were used as query sequences in subsequent BLAST searches to identify putative distantly related subfamilies of LTRs. To be considered an LTR in this study, a sequence had to display >60% sequence homology to the LTR query sequence in a pairwise comparison test (Tatusova and Madden 1999) and have a size no smaller than 40% of the LTR query sequence. Each Cer LTR identified by these criteria was given the name of the Cer family to which it was most homologous, followed by the number of the clone in which it was found. For full-length elements with two LTRs, the 3′ LTR was labeled by a lowercase “b” following the clone number.

Alignments and Phylogenetic Analysis

Using the clone coordinates from the BLAST search, the Cer LTR sequences were copied and placed into individual files. Alignments were created with ClustalW and edited with MacVector 7.0 (http://www.gcg.com). Both ClustalX 1.8 (Thompson et al. 1997) and PAUP 4.03b (Swofford 1999) were used to generate neighbor-joining (NJ) trees with bootstrap values. Trees were viewed with TreeView 1.5.3 (Page 1996).

tRNA Identification

The C. elegans tRNA database was downloaded (http://rna.wustl.edu/tRNAdb/; Lowe and Eddy 1997) for use as a local FASTA database in conjunction with the GCG software package (http://www.gcg.com) maintained by the Research Computing Resource (RCR) at the University of Georgia. One hundred and one nucleotides downstream of each 5′ LTR (including the last nucleotide of the LTR) were used as query sequences in FASTA searches (default parameters) run against the tRNA database to identify matching tRNA 3′ ends complementary to putative Cer PBSs (Goodwin and Poulter 2000).

Chromosomal Position Analyses

The chromosomal position of the 5′ end of each clone found to contain one or more Cer elements was obtained from Wormbase (www.wormbase.org). Endpoints of elements within clones were averaged to obtain a “position value” for each element within a clone. Combining position values of elements within a clone with the position of clones on chromosomes allowed us to assign a chromosomal location to each Cer element. The Kolmogov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit test was used to test the randomness of the distribution of Cer elements among chromosomes and within individual chromosomes. An exponential distribution was used to represent a random dispersal of elements within each chromosome. The observed distribution was calculated based on the base pair distance between sequential element positions along the chromosome.

Gene Annotation

The C. elegans EST database (dbEST-C. elegans) was BLASTed for homology to each Cer LTR sequence. ESTs with significant homology (E = <0.0001) to Cer LTRs were identified. The complete sequences of each EST were then BLASTed against the NCBI C. elegans genome database to identify the corresponding clone containing the LTR and associated gene. TBLASTN searches (default parameters) of these LTR associated genes were run to identify homology to previously characterized genes. GeneFinder (dot.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu) was used to delineate the exon boundaries of the putative genes.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center) from C. elegans cultured under standard conditions on mixed life stage agar plates (Wood 1988). DNA contamination was removed using DNA-free (Ambion). Oligo dT20 primed reverse transcription (RT) was performed on 1 μg of total RNA using the ThermoScript RT-PCR system and protocol from Gibco BRL. RT (−) control reactions to detect DNA contamination contained an equivalent volume of sterile distilled water in lieu of reverse transcriptase.

PCR primers designed with MacVector 7.0 and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies were: 6R55.2 F 5′-ATG ACGATGAGCGGTGC-3′, R 5′-AAAGTGAGATGTGATTGG GG-3′; C56G3.2 F 5′-CAGCAACCTTCCTACACGG-3′, R 5′-CGCAACTCAGATGGAGCAG-3′; F20B4.6 F 5′-AAGGG TTGGGTTTGGTTGGAC-3′, R 5′-TCAAGAACAGAACGCCTC GTCG-3′; and F53E10.5 F 5′-GCGATAGCGTTCTGCTCTT GTG-3′, R 5′-GGCGAATAAATGAAATCACGGAGG-3′ (Fig. 4). Within a locus, PCRs on genomic DNA and cDNAs were performed using the same primer set. The 25 μL PCRs contained 2 μL RT reaction or C. elegans genomic DNA, 30 pmol of each primer, 0.5 U Taq polymerase (Pierce Chemical), 200 μM each dNTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, and 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 9.0. DNA (−) PCR controls to detect potential DNA contamination contained an equivalent volume of sterile distilled water in lieu of genomic DNA. Following an initial denaturation at 95°C/5 min, 35 cycles of 95°C/30 sec, 52° to 56°C (primer dependent)/30 sec, 72°C/1–2 min (depending on maximum expected product length), and a final cycle at 72°C for 10 min were performed on a Hot Top-equipped RoboCycler Gradient 96 (Stratagene). Reaction products (15 μL) and a 100 bp ladder (0.25 μg)(New England Biolabs) were separated on a 1.3% agarose gel in 0.5 × TBE running buffer containing 0.25 μg mL−1 ethidium bromide. Gel images were visualized by UV transillumination and scanned for image processing.

Acknowledgments

We thank King Jordan for statistical advice and Nathan Bowen for reading and commenting on earlier versions of this manuscript. Our laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL mcgene@arches.uga.edu; FAX (706) 542-3910.

Article and publication are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.196201.

REFERENCES

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banki K, Halladay D, Perl A. Cloning and expression of the human gene for transaldolase. A novel highly repetitive element constitutes an integral part of the coding sequence. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2847–2851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes TM, Kohara Y, Coulson A, Hekimi S. Meiotic recombination, noncoding DNA and genomic organization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;141:159–179. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DE, Howe MM. Mobile DNA. Washington, DC.: American Society for Microbiology; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen NJ, McDonald JF. Genomic analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans reveals ancient families of retroviral-like elements. Genome Res. 1999;9:924–935. doi: 10.1101/gr.9.10.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten RJ. Mobile elements inserted in the distant past have taken on important functions. Gene. 1997;205:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius J. RNAs from all categories generate retrosequences that may be exapted as novel genes or regulatory elements. Gene. 1999;238:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: A platform for investigating biology. The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri P, Junakovic N. Revising the selfish DNA hypothesis: New evidence on accumulation of transposable elements in heterochromatin. Trends Genet. 1999;15:123–124. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell RB. Repetitive DNA and chromosome evolution in plants. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986;312:227–242. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame IG, Cutfield JF, Poulter RT. New BEL-like LTR-retrotransposons in Fugu rubripes, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster. Gene. 2001;263:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel DJ. Genetic loose change: How retroelements and reverse transcriptase heal broken chromosomes. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:173–175. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin TJ, Poulter RT. Multiple LTR-retrotransposon families in the asexual yeast Candida albicans. Genome Res. 2000;10:174–191. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MM. Eukaryotic transposable elements as mutagenic agents. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1988. Mobile DNA elements and spontaneous gene mutation; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Haber JE. Lucky breaks: Analysis of recombination in Saccharomyces. Mutation research fundamental and molecular mechanisms of mutagenesis. 2000;451:53–69. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S. Heterochromatin function in complex genomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1470:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedrusik MA, Schulze E. A single histone H1 isoform (H1.1) is essential for chromatin silencing and germline development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 2001;128:1069–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapitonov VV, Jurka J. The long terminal repeat of an endogenous retrovirus induces alternative splicing and encodes an additional carboxy-terminal sequence in the human leptin receptor. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:248–251. doi: 10.1007/pl00013153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Vanguri S, Boeke JD, Gabriel A, Voytas DF. Transposable elements and genome organization: A comprehensive survey of retrotransposons revealed by the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence. Genome Res. 1998;8:464–478. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik HS, Henikoff S, Eickbush TH. Poised for contagion: Evolutionary origins of the infectious abilities of invertebrate retroviruses. Genome Res. 2000;10:1307–1318. doi: 10.1101/gr.145000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JF. Evolution and consequences of transposable elements. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:855–864. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90005-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JF. Transposable elements: Possible catalysts of organismic evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 1995a;10:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)89012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JF. Transposable elements and genome evolution. Boston, MA: Kluewer Academic Press; 1995b. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JF. Genomic imprinting as a co-opted evolutionary character. Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;13:94–95. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medstrand P, Landry JR, Mager DL. Long terminal repeats are used as alternative promoters for the endothelin B receptor and apolipoprotein C-I genes in humans. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1896–1903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y. Retrotransposal integration of mobile genetic elements in human diseases. J Hum Genet. 1998;43:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s100380050045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse RH. RAP, RAP, open up! New wrinkles for RAP1 in yeast. Trends Genet. 2000;16:51–53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01936-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RD. TreeView: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov DA, Lozovskaya ER, Hartl DL. High intrinsic rate of DNA loss in Drosophila. Nature. 1996;384:346–349. doi: 10.1038/384346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel P, Tikhonov A, Jin YK, Motchoulskaia N, Zakharov D, Melake-Berhan A, Springer PS, Edwards KJ, Lee M, Avramova Z, et al. Nested retrotransposons in the intergenic regions of the maize genome. Science. 1996;274:765–768. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surzycki SA, Belknap WR. Repetitive-DNA elements are similarly distributed on Caenorhabditis elegans autosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:245–249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP* Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods). Sunderland, MA: Sinuaer Assoc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova TA, Madden TL. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telsnitsky A, Goff SP. Reverse transcriptase and the generation of retroviral DNA. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Retroviruses. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 121–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng SC, Kim B, Gabriel A. Retrotransposon reverse-transcriptase-mediated repair of chromosomal breaks. Nature. 1996;383:641–644. doi: 10.1038/383641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt VM. Retroviral virions and genomes. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Retroviruses. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 27–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RK. How the worm was won. The C. elegans genome sequencing project. Trends Genet. 1999;15:51–58. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(98)01666-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood WB. The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. pp. 587–606. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Eickbush TH. Origin and evolution of retroelements based upon their reverse transcriptase sequences. EMBO J. 1990;9:3353–3362. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JA, Walsh CP, Bestor TH. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Gabriel A. Patching broken chromosomes with extranuclear cellular DNA. Mol Cell. 1999;4:873–881. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarr J. Biostatistical analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1999. pp. 475–478. [Google Scholar]